Abstract

Background

Physical activity levels are low amongst adolescent girls, and this population faces specific barriers to being active. Peer influences on health behaviours are important in adolescence and peer-led interventions might hold promise to change behaviour. This paper describes the protocol for a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls (PLAN-A), a peer-led intervention aimed at increasing adolescent girls’ physical activity levels.

Methods/design

A two-arm cluster randomised feasibility trial will be conducted in six secondary schools (intervention n = 4; control n = 2) with year 8 (12–13 years old) girls. The intervention will operate at a year group level and consist of year 8 girls nominating influential peers within their year group to become peer-supporters. Approximately 15 % of the cohort will receive 3 days of training about physical activity and interpersonal communication skills. Peer-supporters will then informally diffuse messages about physical activity amongst their friends for 10 weeks. Data will be collected at baseline (time 0 (T0)), immediately after the intervention (time 1 (T1)) and 12 months after baseline measures (time 2 (T2)). In this feasibility trial, the primary interest is in the recruitment of schools and participants (both year 8 girls and peer-supporters), delivery and receipt of the intervention, data provision rates and identifying the cost categories for future economic analysis. Physical activity will be assessed using 7-day accelerometry, with the likely primary outcome in a fully-powered trial being daily minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Participants will also complete psychosocial questionnaires at each time point: assessing motivation, self-esteem and peer physical activity norms. Data analysis will be largely descriptive and focus on recruitment, attendance and data provision rates. The findings will inform the sample size required for a definitive trial. A detailed process evaluation using qualitative and quantitative methods will be conducted with a variety of stakeholders (i.e. pupils, parents, teachers and peer-supporter trainers) to identify areas of success and necessary improvements prior to proceeding to a definitive trial.

Discussion

This paper describes the protocol for the PLAN-A feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial which will provide the information necessary to design a fully-powered trial should PLAN-A demonstrate evidence of promise.

Trial Registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amongst children and adolescents, physical activity (PA) is associated with lower levels of cholesterol and blood lipids and favourable blood pressure and body composition [1]. There is also evidence that PA is associated with young people’s mental health [2] and academic performance [3]. Despite the benefits of being physically active during the early years, PA levels decline during childhood [4]. Throughout childhood and adolescence, girls are less active than boys [5] and the age-related decline in PA (particularly from early adolescence) is steeper for girls. In England, when measured objectively, 96 % of girls aged 11–15 years performed less than 30 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) per day and none met government recommendations of 60 min of MVPA per day [6].

The psychological correlates of adolescent girls’ PA participation include enjoyment, perceived competence, self-efficacy and physical self-perceptions [7]. Further, qualitative research suggests that these factors are intertwined with girls’ social (often school) context and changes to friendship groups, peer support, perceived competence, competing priorities, self-presentational concerns and ‘sporty’ gender stereotypes experienced during the transition from primary to secondary school which may also contribute to the observed decline in girls’ PA [8–10]. PA interventions aimed at girls have produced small but significant positive effects and larger effects have been observed for interventions that targeted girls only and used educational and multi-component designs [11]. As such, while it may be possible to increase girls’ PA, new and more effective interventions are needed.

Promoting young people’s health in schools is a public health priority [12], and school-based interventions can reach many young people over a sustained period. However, a 2009 Cochrane review of school-based PA interventions showed that none were conducted in the UK that involved adolescents and the non-UK interventions for adolescents did not increase PA [13]. Current school-based interventions have focussed on ‘top-down approaches of providing education and short-term structured PA’ [13], and there is a need for alternative designs. One approach is to develop interventions which capitalise on naturally occurring determinants within target populations and sustainable health promotion mechanisms (i.e. peer groups and their influence on PA) to promote long-term PA behaviour.

Peers play a central role in influencing adolescents’ PA and its determinants through providing peer support, co-participation in PA, peer norms, friendship quality, peer affiliation and peer victimisation [14]. This is supported by social network research which has shown that adolescents choose friends who are similarly active and that they may alter their PA over time to be more like their friends’ [15]. This work highlights the potential promise of interventions, especially amongst girls, to increase PA which capitalise on existing peer processes in schools by promoting peer support and enhancing peer communication skills [14].

Peer-led interventions have targeted a range of health behaviours amongst young people, including smoking, asthma, alcohol consumption, drug use, PA and sedentary behaviour [16–18]. A recent review of ten peer-led PA interventions [18] found that only two targeted young people: one small special population [19] and one insufficiently-reported study [20], and neither was conducted in the UK. Overall, consistent positive effects of the interventions on PA behaviour were reported, suggesting that peer-led interventions are viable; however, the existing research is limited by a lack of high quality controlled trials amongst adolescents, interventions which are largely atheoretical and a sole focus on formal methods of peer-peer delivery (e.g. leading educational classes, organised co-participation and formal advice giving) which are both time limited and intensive.

An alternative peer-led approach is to train peer-supporters to informally diffuse health promotion messages to their peers. This approach is based on Diffusion of Innovations theory [21] which conceptualises how ideas, beliefs or behaviours are informally communicated through members of a social system. This theory was adopted in the ASSIST (A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial) study [16]. The ASSIST intervention involves asking pupils within a school year group to nominate influential peers. The nominated individuals then receive training to informally diffuse messages to their peers about the target health behaviour (e.g. not smoking) for 10 weeks. In a cluster randomised controlled trial of ASSIST, which comprised 10,730 school children aged 12–13 years from England and Wales, those who received the intervention had lower odds of being a smoker compared to pupils in the control condition immediately after the intervention (OR = 0.75, 95 % CI = 0.55 to 1.01) and at 1 (OR = 0.77, 95 % CI = 0.59 to 0.99)- and 2 (OR = 0.85, 95 % CI = 0.72 to 1.02)-year follow-up [16].

The ASSIST model was adopted in an exploratory trial of the Activity and Healthy Eating in ADolecence (AHEAD) project, an obesity prevention intervention which targeted the diffusion of PA and healthy eating messages amongst 12- to 13-year-olds [22]. Although feasible to implement and well received, the intervention did not show evidence of promise to increase healthy eating or PA. It was concluded that targeting two behaviours was too complex and the healthy eating component was resource intensive and costly [22]. The results of ASSIST and AHEAD suggest that while informal school-based peer-led interventions can be effective in changing young people’s health behaviours, behaviour change messages intended for peer-diffusion need to be simple and may benefit from targeting more specific behavioural determinants of particular populations. No previous studies have used the Diffusion of Innovations approach to specifically increase PA levels of adolescent girls [21].

Interventions which target theoretical mechanisms of behaviour change are likely to be more effective than those that do not [23], yet few peer-led PA interventions incorporate theoretical principles [18]. Diffusion of Innovations theory remains a fundamental framework for harnessing the influential capacities of change agents (e.g. year 8 girls identified as opinion leaders by their peers); however, it does not help guide either the content or the behaviour change techniques adopted in the peer-training intervention. Self-determination theory (SDT) [24] is a framework which concerns the personal and social conditions needed to foster high quality motivation for behaviour change and has been used to understand motivation for PA amongst children and adolescents [10, 25, 26] and guide PA interventions [27], including a peer-led PA intervention for older adults [28]. SDT contends that autonomous motivation for PA (based on authentic choices, inherent satisfaction or personal value) is associated with positive behavioural, affective and cognitive outcomes, whereas controlled motivation (based on guilt or compliance with others’ demands) undermines these outcomes. Autonomous motivation is supported by the degree to which the social environment satisfies, and individuals perceive the satisfaction of three psychological needs: autonomy, competence and social belonging. Research amongst children, adolescents and adults has identified positive associations between autonomous versus controlled motivation and PA [26, 29], positive affect, challenge-seeking [29] and quality of life [30]. SDT is well suited to a peer-led intervention model because peer-supporters can create a social climate that can either undermine or facilitate their friends’ interest in PA [18]. It is also possible that peer-supporters could create a social environment which is supportive of other antecedents to autonomous motivation including health and affiliation motives, perceptions of competence, connectedness and social support and realistic choices and options of how to be physically active [8, 10].

Study objectives

The aim of this study is to assess the feasibility of the ‘PLAN-A’ (Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls) peer-led PA intervention, adapted from the ASSIST model, which is designed to increase the PA of adolescent girls. In a definitive trial, the primary research question would test the effectiveness of the PLAN-A intervention in increasing the PA levels of year 8 girls. The aims of this feasibility study are to:

-

1.

Estimate the recruitment rate of year 8 girls as peer-supporters and non-peer-supporters and monitor their attendance at peer-supporter training.

-

2.

Qualitatively examine the acceptability of the intervention to pupils, peer-supporter trainers, schools and parents and identify necessary refinements.

-

3.

Estimate accelerometer and questionnaire data provision rates, examine data quality and explore the implications of missing accelerometer data in terms of how these data might be imputed in a definitive trial.

-

4.

Estimate the potential effect of the intervention on daily accelerometer-derived MVPA and secondary PA-related and psychological variables immediately after the intervention (time 1 (T1)) and at 12 months after baseline (time 2 (T2)).

-

5.

Estimate the school-related intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for daily MVPA, combining data from this project with our data from other local secondary schools.

-

6.

Estimate the sample size for an adequately powered definitive trial evaluation.

-

7.

Identify and test the feasibility of collecting the data needed to cost the intervention and conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis in a definitive trial.

-

8.

Examine the consent rate (participants and data custodians) for data linkage to academic achievement, attendance and health records.

Methods/design

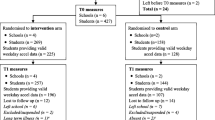

The design is a two-arm cluster randomised controlled trial comparing the PLAN-A intervention against a usual-practice control conducted in six secondary schools, of which four schools will receive the intervention and two will serve as controls. Data will be collected at three time points: baseline (time 0 (T0)), immediately after the 10 week intervention (T1) and 12 months post-baseline (T2, 5–6 months post-intervention). Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram. The project has been approved by the research ethics committee of the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol (Ref: SPSREC14-15.A27).

Setting

Eligible settings will be state-maintained secondary schools in Wiltshire and South Gloucestershire, in South West England, which are above the median of the local Pupil Premium Indicator (i.e. more deprived) (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pupil-premium-2015-to-2016-allocations). Special educational needs schools will be excluded. The feasibility trial will be conducted in six secondary schools, three from each area.

Recruitment

School recruitment

The ASSIST programme is delivered in some schools in the study areas, and it would not be possible to run ASSIST and PLAN-A concurrently within the context of a randomised controlled trial (RCT). As such, the study team will work with Wiltshire and South Gloucestershire collaborators to identify schools where ASSIST is not delivered. The remaining schools will be invited to participate via a letter and follow up emails to the respective head teachers and other relevant school staff. Schools which express interest will be contacted and provided with further information. Reserve schools will be recruited to allow for school withdrawal prior to baseline data collection.

Student recruitment

In participating schools, a presentation will be made to all girls in year 8 (in the first term of year 8) to inform them about the trial. This will include details on the intervention, control conditions and the chance of the school being in either condition. All girls will be given study information for themselves and their parents. All year 8 girls in participating schools will be eligible to take part in the study.

Consent

As the intervention operates at a year group level, consent for pupils to participate in the trial will be sought through parent opt-out consent. Parent and child information sheets and opt-out forms will be distributed to all year 8 girls (in an envelope addressed to ‘Parents’) at the point of recruitment and need to be returned prior to baseline data collection. Parents of girls invited to be peer-supporters will be asked to provide written informed consent to allow their daughter to participate in the peer-supporter training. Peer-supporters will also be asked to assent to this role. Adult participants (e.g. peer-supporter trainers, school contacts and parents) will be asked to provide written informed consent if selected for a post-intervention process evaluation interview. Parents of study pupils and pupils themselves will be asked to consent to a hypothetical data linkage scenario separately to consenting to the trial (i.e. data linkage will not be performed, but we will examine the consent rate). Data custodians (i.e. schools or Local Authorities (LAs)) will also be asked to consent to a hypothetical data linkage scenario to assess the feasibility of linking pupils’ study identification number to educational attainment, attendance and health data held by LAs as an efficient means of obtaining such data.

Allocation strategy

School is the unit of randomisation. Six schools will be randomly allocated, stratified by LA area (Wiltshire vs. South Gloucestershire), after baseline data collection has been completed, at an intervention to control ratio of 2:1 within LA area. Four schools will be allocated to the intervention arm and two schools allocated to the control arm. Allocation will be performed (computer generated allocation) by an independent member of the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration who will be blind to the school identity. The statistician and all team members apart from the Project Manager, Research Assistants and Fieldworkers will be blind to the allocation of schools to trial arms.

The PLAN-A intervention

The PLAN-A intervention is based on the ASSIST [16] model and involves the following components: (a) train-the-trainers programme, (b) peer-nomination, (c) peer-supporter training and (d) a 10-week informal health message peer-diffusion period. These elements are described below.

Peer nomination

All year 8 girls who have not been opted-out of the study in the six schools will be asked to complete a peer nomination questionnaire (as used in ASSIST), in which they identify the female peers they perceive to be influential in their year at school. Nomination will take place before randomisation of schools, and the girls who are nominated in what later become the intervention schools will be alerted to this soon after randomisation. The highest scoring 18 % (those with most nominations) within intervention schools will be invited to be peer-supporters. These girls will attend an in-school recruitment meeting with a study staff member. The meeting will outline the peer-supporter role, and pupil and parent information sheets and consent forms will be handed out. Pupils can opt-out of being a peer-supporter at this point. It is expected that ≥15 % of the year group take on the peer-supporter role, as outlined in Diffusion of Innovations theory [21].

Train-the-trainers programme

The girls who consent to the peer-supporter role will receive peer-supporter training (see below). This will be delivered by two peer-supporter trainers who will have attended a 3-day (≈15 h) education programme delivered by the study team. Peer-supporter trainers will be individuals who have either health promotion/PA knowledge (e.g. members of LA Healthy Lifestyles teams) and/or experience of facilitating group work with young people (e.g. youth workers, theatre company members). Training will cover the background to the project, fundamentals of Diffusion of Innovations and SDT, key information about PA and all session plans and activities. Training will be practical and provide opportunities to rehearse session delivery. Trainers will be provided with an intervention manual which will include all the logistical details, session plans and resources needed to deliver the training. Trainers will be reimbursed at an hourly rate to attend the train-the-trainers programme and deliver the peer-supporter training.

Peer-supporter training

Peer-supporters will attend a 2-day course to develop their skills, knowledge and confidence to promote PA amongst peers. Training will be held off-site and led by two external peer-supporter trainers who will have attended the train-the-trainers programme. The peer-supporter training will build on transferable activities from the previously used ASSIST and AHEAD training and include content focused on PA and interpersonal skills and personal qualities needed to be a peer-supporter. The key components of the peer-supporter training are shown in Table 1 alongside how the intervention components map on to behaviour change techniques [31] and SDT constructs. The content will be informed by SDT and will aim to build the girls’ perceived autonomy, competence and sense of social support for being a peer-supporter and for PA. Peer-supporters will be encouraged to keep these concepts in mind when having informal conversations with their peers. At the approximate mid-point of the 10-week intervention period (see below), peer-supporters will attend a 1-day top-up training event which will follow a similar format to the first 2 days and focus on sharing experiences, problem solving and reinforcing key messages about PA and peer-supporting. Lunch and refreshments will be provided at all training days. Training will take place on school days.

10-week informal health message peer-diffusion period

Following the training, peer-supporters will be asked to informally promote messages about increasing PA amongst their peers for 10 weeks. Peer-supporters can support anyone they choose, although encouragement will be given in the training for peer-supporters to focus their support on girls in their year group. Peer-supporters will be given a diary to record the nature of the conversations that they have with their peers about PA. During the intervention period, peer-supporters will be able to refer to the study website for tips and email questions that they have to a dedicated study email address which will be answered and shared, anonymously, on the website as Frequently Asked Questions to help other peer-supporters.

Control group provision

Two schools will be randomly assigned to the control arm after baseline (T0) data collection and will not receive the PLAN-A intervention. These schools will continue with their normal practice. Year 8 pupils in control schools will participate in data collection at T0, T1 and T2.

School and student appreciation

All participating schools (intervention and control) will receive a £500 donation and a summary of the research findings at the end of the project in recognition of the time devoted to accommodating the study. To maximise timely return of accelerometers and in recognition of the time given to each data collection, all participants will receive a voucher (T0 £5, T1 £10, and T2 £10).

Measures

Recruitment, retention and attendance

Key outcomes are recruitment of schools, pupils, peer-supporters and peer-supporter trainers. Recruitment rates of schools and peer-supporter trainers will be recorded. Opt-out consent and assent rates of year 8 girls to participate in the trial will be recorded. We will record attendance of the invited peer-supporters to the recruitment meeting, rate of consent (parents) and assent (pupils) to the peer-supporter role and attendance at the peer-supporter training and top-up training.

Outcome measures

All measures will be taken at baseline (T0), immediately after the intervention period (T1) and 12 months after baseline (T2). The likely primary outcome in a definitive trial would be weekday minutes of MVPA per day, measured by accelerometry. This method can provide reliable estimates of young people’s PA and is validated amongst young people [32]. Participants will be asked to wear an ActiGraph wGT3X-BT accelerometer for 7 days at T0, T1 and T2. Periods of ≥60 min of zero counts will be recorded as non-wear and removed. Participants will be included in analysis if they provide at least 2 days of valid weekday data (i.e. 500 min of data between 05:00 and 23:59). Mean minutes of daily MVPA will be estimated using the Evenson [33] cut-point which has been found to be the most accurate threshold for adolescents [34]. The intervention could reduce the amount of time participants spend sedentary and/or their mode of travel to school (i.e. active vs. passive). As such, in addition to exploring other potential secondary outcomes (e.g. minutes of MVPA on weekend days and the proportion of girls meeting government physical activity recommendations), we will estimate participants’ sedentary time using accelerometery based on a cut-point of less than 100 cpm [33]. To provide an indication of change in sedentary behaviours, we will also assess pupil self-reported screen-viewing at T0, T1 and T2 [35]. Participants will also report their usual travel mode to and from school at each time point.

At all time points, the following psychosocial variables will be assessed by self-report questionnaire: autonomous and controlled motivation for PA [36], autonomy [29], competence [37] and relatedness [29] need satisfaction in PA, self-esteem [38], PA self-efficacy [39], PA social support from friends [40] and PA peer norms [41]. These may form secondary outcomes or mediators in a definitive trial. At each time point, pupils will also self-report two items developed for this study to assess year-group-based peer support for PA: ‘Has anyone in your year group talked with you recently about physical activity?’ (Yes, No, I’m not sure) and ‘Did talking to any one in your year help you to be more active?’ (Yes, No, I’m not sure, I didn’t speak to anyone). The EQ-5D-Y [42] will be used to measure self-reported quality of life at each time point. At T0 only, participants will complete additional questionnaire items to report demographic information.

Process evaluation

A detailed process evaluation will examine acceptability of the intervention and methods, intervention delivery and implementation, potential intervention mechanisms and the influence of school context [43] using qualitative and quantitative approaches amongst peer-supporters, non-peer-supporter pupils, peer-supporter trainers, parents of peer-supporters and school contacts. The process evaluation methods are shown in Table 2.

Economic data

Data will be collected to estimate intervention costs and examine the feasibility of calculating cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a definitive trial. Resource use data, including intervention materials, venue costs, staff, trainer and pupil time, expenses, travel and administration costs, will be collected prospectively during each stage of the intervention using expense claim forms and data collection forms completed by the research team and school contact.

Sample size

As the study is a feasibility trial, a formal power calculation based on detecting evidence for effectiveness has not been conducted. The feasibility RCT will be conducted in six schools (four interventions, two controls). Based on recent experience in local secondary schools, we anticipate that there will be between 60 and 100 female pupils in year 8 per school. Therefore, we expect that the sample size will range between 360 and 600 girls, including between 36 and 60 peer-supporters from the four intervention schools. This is a pragmatically chosen sample to allow us to identify evidence of feasibility, recruitment rates and any problems with the intervention or research methods. An aim of the feasibility study is to calculate the required sample size for a definitive cluster RCT evaluation of the PLAN-A intervention. As such, we will estimate the variability in the likely definitive trial outcome (minutes of MVPA per day) using an ICC. Commensurate with recent recommendations [44] and as the ICC for MVPA in the study will be derived only from six schools, to obtain a more accurate ICC estimate for inclusion in a power calculation for a definitive trial, the ICC will be informally compared to those obtained in our previous research which has used the same measures amongst adolescent girls (e.g. Bristol Girls’ Dance Project) [45].

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

The main outcomes in this feasibility trial are the consent and recruitment rates (year 8 cohorts and peer-supporters), number and proportion of peer-supporters who receive training, and data provision rates. Analysis of these data will be mainly descriptive (means and SD, or N and %) as appropriate. Descriptive comparisons of these data will be made between intervention and control arms. Loss to follow-up in intervention and control groups will be reported. The implications of missing accelerometer data will be investigated using multiple imputations. Demographic characteristics will be summarised descriptively as appropriate.

Evidence of promise (i.e. whether the intervention could lead to an increase in daily MVPA) will be examined using appropriate multivariable linear regression models to compare between group differences in means and 95 % CIs of MVPA, adjusted for baseline PA and clustering of participants within schools. As the study is not powered to detect effectiveness, p values will not be considered and the focus will be on whether the 95 % CIs include a meaningful difference in MVPA. Based on previous research [46], sample sizes for a future definitive trial will be based on detecting a 10-min per day difference in MVPA between trial arms, estimated using the ICC for daily MVPA and based on combinations of different alpha (i.e. significance level) and beta (i.e. power) rates.

A public sector perspective will be taken in the economic analysis. Where available, national unit costs for staff time will be used to increase the generalisability of findings. Cost per pupil will be estimated by dividing the costs of the peer-supporter programme at each school by the number of female participants in the school year group. We will calculate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) by dividing the mean cost per pupil of the intervention by the difference in daily MVPA in the intervention and control schools. The analysis is designed to explore the affordability and potential cost-effectiveness of the intervention rather than provide a definitive comparison.

Qualitative analysis

Recordings of interviews and focus groups will be transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis [47] will be used to analyse these data. Transcripts will be read and reread, and initial codes that categorise the content of each transcript will be produced. These initial codes will then be iteratively refined to produce emergent themes. We will examine divergence and convergence within and between interviews and focus groups and compare the experiences of the intervention across the different participant groups to develop a comprehensive understanding of the intervention acceptability, implementation and mechanisms of impact.

Further details on the statistical and economic and qualitative analysis plans will be made available on the study website (www.plan-a-project.org).

Discussion

The PLAN-A feasibility trial aims to use a peer-led intervention to increase the PA of 12–13-year-old girls. As PA levels are low amongst British girls and decrease from childhood to adolescence [4], new intervention approaches are needed which are tailored to the unique determinants of PA amongst adolescent girls and harness the potential power of their existing and accepted social networks. The PLAN-A intervention builds on the effective ASSIST peer-led smoking cessation intervention model and the feasibility trial aims to assess the potential of this approach to increase adolescent girls’ PA. The study will also provide the information needed to design a definitive cluster RCT should evidence of promise be shown.

Trial status

The feasibility trial is registered with the ISRCTN (ISRCTN12543546). Ethical approval for the project was received from the Research Ethics Committee of the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol (Ref: SPSREC14-15.A27)). Pupil recruitment and baseline (T0) data collection are planned for September/October 2015.

Abbreviations

- AHEAD:

-

Activity and Healthy Eating in ADolecence

- ASSIST:

-

A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial

- ICC:

-

intraclass correlation coefficient

- ICER:

-

incremental cost effectiveness ratio

- LA:

-

Local Authority

- MVPA:

-

moderate to vigorous physical activity

- PA:

-

physical activity

- PLAN-A:

-

Peer-Led physical Activity iNtervention for Adolescent girls

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

- SDT:

-

self-determination theory

- T0, T1, T2:

-

time 0, time 1, time 2

References

Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40.

Biddle SJ, Asare M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(11):886–95.

Booth JN, Leary SD, Joinson C, Ness AR, Tomporowski PD, Boyle JM et al. Associations between objectively measured physical activity and academic attainment in adolescents from a UK cohort. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(3):265–70.

Dumith SC, Gigante DP, Domingues MR, Kohl HW, 3rd. Physical activity change during adolescence: a systematic review and a pooled analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):685–98.

Nader PR, Bradley RH, Houts RM, McRitchie SL, O'Brien M. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(3):295–305.

Townsend N, Bhatnager P, Wickramasinghe KK, Scarborough P, Foster C, Rayner M. Physical Activity Statistics 2012. London: British Heart Foundation; 2012.

Biddle SJH, Whitehead SH, O'Donovan TM, Neville ME. Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: a systematic review of recent literature. J Phys Act Health. 2005;2:421–32.

Slater A, Tiggemann M. “Uncool to do sport”: a focus group study of adolescent girl’s reasons for withdrawing from physical activity. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11(6):619–26.

Knowles AM, Niven AG, Fawkner SG. Adopting a narrative approach to understanding physical activity behaviour in adolescent girls. Qual Res Sport Exerc & Health. 2013;6:62–76.

Gillison F, Sebire S, Standage M. What motivates girls to take up exercise during adolescence? Learning from those who succeed. Brit J Health Psychol. 2011;17(3):536–550.

Biddle SJ, Braithwaite R, Pearson N. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity among young girls: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2014;62C:119–31.

Lemer C. Annual Report of the CMO, Our Children Deserve Better. 2012.

Dobbins M, De Corby K, Robeson P, Husson H, Tirilis D. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6–18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD007651.

Fitzgerald A, Fitzgerald N, Aherne C. Do peers matter? A review of peer and/or friends’ influence on physical activity among American adolescents. J Adolesc. 2012;35(4):941–58.

Macdonald-Wallis K, Jago R, Sterne JA. Social network analysis of childhood and youth physical activity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(6):636–42.

Campbell R, Starkey F, Holliday J, Audrey S, Bloor M, Parry-Langdon N et al. An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1595–602.

Mellanby AR, Rees JB, Tripp JH. Peer-led and adult-led school health education: a critical review of available comparative research. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(5):533–45.

Martin Ginis KA, Nigg CR, Smith AL. Peer-delivered physical activity interventions: an overlooked opportunity fo physical activity promotion. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:434–43.

Lieberman LJ, Dunn JM, van der Mars H, McCubbin J. Peer tutors’ effects on activity levels of deaf students in inclusive elementary physial education. Adapt Phys Act Q. 2000;17:20–39.

Thomas AB, Ward E. Peer power: how dare county, North Carolina, is addressing chronic disease throught innovative programming. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2006;12(5):462–7.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. NY: The Free Press; 1983.

Bell S, Audrey S, Cooper A, Noble S, Campbell R. Lessons from a peer-led obesity prevention programme in English schools. Health Promotion International, 2014; doi:10.1093/heapro/dau008.

Michie S. Designing and implementing behaviour change interventions to improve population health. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13 Suppl 3:64–9.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:227–68.

Teixeira PJ, Carraca EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Ryan RM. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 2012, 9:78.

Sebire SJ, Jago R, Fox KR, Edwards MJ, Thompson JL. Testing a self-determination theory model of children’s physical activity motivation: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:111.

Fortier MS, Duda JL, Guerin E, Teixeira PJ. Promoting physical activity: development and testing of self-determination theory-based interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:20.

Buman MP, Giacobbi PR, Dzierzewski JM, Morgan A, McCrae CS, Roberts BL et al. Peer volunteers improve long-term maintenance of physical activity with older adults: a randomised controlled trial. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8:S257–66.

Standage M, Duda JL, Ntoumanis N. A test of self-determination theory in school physical education. Br J Educ Psychol. 2005;75:411–33.

Gillison F, Standage M, Skevington SM. Relationships among adolescents’ weight perceptions, exercise goals, exercise motivation, quality of life and leisure-time exercise behaviour: a self-determination theory approach. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:836–47.

Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26(11):1479–98.

Welk GJ, Schaben JA, Morrow JR. Reliability of accelerometry-based activity monitors: a generalizability study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1637–45.

Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(14):1557–65.

Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, Pfeiffer KA. Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1360–8.

Cillero IH, Jago R, Sebire S. Individual and social predictors of screen-viewing among Spanish school children. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(1):93–102.

Markland D, Tobin VJ. A modification to the behavioural regulation in exercise questionnaire to include an assessment of amotivation. J Sport & Exerc Psychol. 2004;26:191–6.

McAuley E, Duncan T, Tammen VV. Psychometric properties of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory in a competitive sport setting: a confirmatory factor-analysis. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1989;60(1):48–58.

Marsh HW. Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ) II: a theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of multiple dimensions of adolescent self-concept. NSW, Australia: University of Western Sydney; 1992.

Bartholomew JB, Loukas A, Jowers EM, Allua S. Validation of the physical activity self-efficacy scale: testing measurement invariance between Hispanic and Caucasian children. J Phys Act Health. 2006;3:70–8.

de Farais Junior JC, Da Silva Lopes A, do Nascimento JV, Borgatto AF, Hallal PC. Development and validation of a questionnaire measuring factors associated with physical activity in adolescents. Brazil J Mother Infant Health. 2011;11(2):301–12.

Ling J, Robbins LB, Resnicow K, Bakhoya M. Social support and peer norms scales for physical activity in adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(6):881–9.

Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burstrom K, Cavrini G, Devlin N et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86.

Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, Foy R, Guthrie B. Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials. 2013;14:15.

Elley CR, Kerse NM, Arroll B. Why target sedentary adults in primary health care? Baseline results from the Waikato Heart, Health, and Activity Study. Prev Med. 2003;37(4):342–8.

Jago R, Edwards MJ, Sebire SJ, Cooper AR, Powell JE, Bird E et al. Bristol girls dance project (BGDP): protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial of an after-school dance programme to increase physical activity among 11–12 year old girls. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1003.

Ekelund U, Luan J, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Griew P, Cooper A et al. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2012;307(7):704–12.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Amorose AJ, Anderson-Butcher D. Autonomy-supportive coaching and self-determined motivation in high school and college athletes: a test of self-determination theory. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2007;8(5):654–70.

Acknowledgements

The work was undertaken with the support of The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Joint funding (MR/KO232331/1) from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. This study was designed and delivered in collaboration with the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC), a UKCRC Registered Clinical Trials Unit in receipt of National Institute for Health Research CTU support funding. None of the funders had involvement in the Trial Steering Committee, the data analysis, data interpretation, data collection or writing of the paper. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily any of the funding bodies listed here.

RAL receives funding through the Farr Institute of Health Informatics Research. The Farr Institute is supported by a consortium of ten UK research organisations: Arthritis Research UK, the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Medical Research Council, the National Institute of Health Research, the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research (Welsh Government) and the Chief Scientist Office (Scottish Government Health Directorates), the Wellcome Trust. MRC Grant No: MR/K006525/1.

The sponsor of this study are University of Bristol, Research and Enterprise Development, 3rd Floor, Senate House, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol, and BS8 1TH, UK www.bristol.ac.uk/red/

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Public Health Research Programme) (project number 13/90/16). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Public Health Research Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

RC is a board member of DECIPHer Impact, a not for profit company that sells the DECIPHer-ASSIST smoking prevention programme (formerly known as ASSIST). There are no further competing interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived by SJS, RJ, RC, WH, RK, PB and RAL. MJE is the Project Manager, KB is the qualitative Research Assistant, KG is the health economics analyst, JS is the trials unit coordinator and KT is the project statistician. The first draft of this manuscript was written by SJS with input from all other authors. All authors have edited and critically reviewed the paper for intellectual content and approved the final version of the paper.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sebire, S.J., Edwards, M.J., Campbell, R. et al. Protocol for a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a peer-led school-based intervention to increase the physical activity of adolescent girls (PLAN-A). Pilot Feasibility Stud 2, 2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-015-0045-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-015-0045-8