Abstract

Background

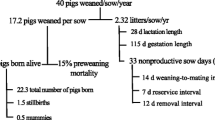

Repeat-breeder females increase non-productive days (NPD) and decrease herd productivity and profitability. The objectives of the present study were 1) to define severe repeat-breeder (SRB) females in commercial breeding herds, 2) to characterize the pattern of SRB occurrences across parities, 3) to examine factors associated with SRB risk, and 4) to compare lifetime reproductive performances of SRB and non-SRB females. Data included 501,855 service records and lifetime records of 93,604 breeding-female pigs in 98 Spanish herds between 2008 and 2013. An SRB female pig was defined as either a pig that had three or more returns. The 98 herds were classified into high-, intermediate- and low-performing herds based by the upper and lower 25th percentiles of the herd mean of annualized lifetime pigs weaned per sow. Multi-level mixed-effects logistic regression models with random intercept were applied to the data.

Results

Of 93,604 females, 1.2% of females became SRB pigs in their lifetime, with a mean SRB risk per service (± SEM) of 0.26 ± 0.01%. Risks factors for becoming an SRB pig were low parity, being first-served in summer, having a prolonged weaning-to-first-mating interval (WMI), and being in low-performing herds. For example, served gilts had 0.81% higher SRB risk than served sows (P < 0.01). Also, female pigs in a low-performing herd had 1.19% higher SRB risks than those in a high-performing herd. However, gilt age at-first-mating (P = 0.08), lactation length (P = 0.05) and number of stillborn piglets (P = 0.28) were not associated with becoming an SRB female. The SRB females had 14.4–16.4 fewer lifetime pigs born alive, 42.8–91.3 more lifetime NPD, and 2.1–2.2 lower parities at culling than non-SRB females (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

We recommend that producers closely monitor the female pig groups at higher risk of becoming an SRB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately 7% of first-served female pigs are re-served in commercial herds [1]. Furthermore, a study of 539 U.S.A. herds reported that 17–20% of the re-served females had a second re-service, and also that 22–27% of the second-return females had a total of three or more re-service occurrences [2]. A recent study also indicated that culling guidelines for third-returned females are not always strictly implemented [3], and so a substantial number of severe repeat-breeder (SRB) female pigs may exist in commercial herds, thus increasing non-productive days (NPD) and affecting herd productivity [4]. Meanwhile, there is no clear and consistent definition for repeat-breeder females in previous studies. Repeat-breeding has been defined as one return [5, 6], while SRB has been defined as one to four returns and culled [7]. Furthermore, there is little information about SRB females in commercial herds, such as their lifetime performance, nor how the reproductive performance in parities before a re-service occurrence differs from that of non-SRB females.

Re-servicing has been associated with lower parity and summer serving [8,9,10]. Other factors that have been associated with lower farrowing rate and more returns are higher pre-service outdoor temperature and prolonged weaning-to-first-mating interval (WMI; [9, 11, 12]). Additionally, a high abortion risk, which is one of the reasons for return occurrences, is also associated with an increased number of stillborn piglets [13]. However, risk factors for SRB females have not been quantified, nor has the pattern of SRB females across parities been examined in detail. Therefore, the objectives of this study were 1) to define SRB females in commercial breeding herds, 2) characterize SRB females across parities, 3) to quantify factors associated with SRB risk, 4) to compare lifetime reproductive performances of SRB and non-SRB females, and 5) to compare reproductive performance of SRB and non-SRB sows in the parity before the SRB sows had their SRB occurrence.

Methods

Study herds

A consultancy firm (PigCHAMP Pro Europa S.L. Segovia, Spain) has requested all client producers to mail their data files since 1998. At the end of 2013, 98 out of the 120 Spanish client herds (82%) allowed their herd data to be used for research purposes. In 2013 the database included approximately 0.7% of all herds in Spain, one of the major pig producing regions in Europe. There are 2,568,450 female pigs in 19,630 breeding herds in Spain [14].

These herds use natural or mechanical ventilation in their farrowing, breeding and gestation barns. The lactation and gestation diets are formulated using cereals (barley, wheat and corn) and soybean meal. Also, all the herds use artificial insemination; double or triple inseminations of sows during an estrous period are practiced for breeding management. Replacement gilts in the herds were either purchased from breeding companies or were home-produced through internal multiplication programs.

Study design, data collection and exclusion criteria

The present study was designed as a retrospective cohort study coordinating by-parity service records from herd entry to removal for female pigs entered the herds from 2008 to 2010, using the PigCHAMP recording system at the end of 2013. Service record were collected from January 2008 to June 2013, because the female pigs lived up to 3 years. At the time the records were collected, 4842 (4.8%) of the 99,533 female pigs had not yet been removed from the herds and so these records were excluded when lifetime records were analyzed. Thus, the initial data contained 517,222 service records in 465,947 parity records and lifetime records of 94,691 females in the 98 herds. Female pigs were excluded if they had NPD of more than 289 days (99th percentile; 949 records), because these data were likely to be incorrectly recorded.

Service records of sows were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: total number of pigs born was 0 pigs or 26 pigs or more (215 records; [15]); lactation length of either 0–9 days or greater than 41 days (3756 records; [16]); WMI of 36 days or more (3779 records; [16]); re-service intervals of 151 days or more (479 records). Hence, the data included 501,855 service records in 454,058 parity records of 93,604 female pigs. Additionally, records with no gilt age at first-mating (AFM) or with an AFM of either less than 160 days or more than 401 days (6767 females; [16]) were excluded when the combined gilts and sows model was used. Two datasets were created from the data, containing lifetime performance (Dataset 1) and service records for consecutive parities (Dataset 2).

Definitions and categories

An SRB female pig was defined as a pig that had had three or more returns within the same parity, based on a modification of the definition used for RB cows [17]. The SRB risk (%) was defined as the number of SRB females divided by the number of first-served females. A re-served female pig was defined as a pig that had more than one service event within the same parity. The first, second and third returns were defined as the first, second and third returns-to-service within the same parity, respectively. A service included one or more inseminations or natural matings during an estrus period. Re-service intervals were categorized into four groups: early, regular, irregular, and late returns, with respective re-service intervals of 11 to 17, 18 to 24, 25 to 38 and 39 to 150 days post-service [8].

Annualized lifetime pigs weaned per sow was defined as the lifetime number of weaned pigs divided by the sum of the reproductive herd life days × 365 days. Reproductive herd life days was defined as the number of days from the date that the gilts was first-inseminated to its removal [18]. Lifetime NPD was defined as the number of days when a female was neither gestating nor lactating during her reproductive herd life. Lifetime pigs born alive was defined as the sum of the number of pigs born alive in a sow’s lifetime.

Three categories of herd productivity were defined on the basis of the upper and lower 25th percentiles of the herd means of annualized lifetime pigs weaned per sow: high-performing herds (> 24.7 pigs), intermediate herds (24.7 to 21.2 pigs) and low-performing herds (< 21.2 pigs). Mean (± SEM) herd size between 2008 and 2013 was 699 ± 64.3 females with a range between 81 and 3222 females.

Removal types included culling and death. Culling due to reproductive failure included culling due to being found not pregnant, repeats and abortion. Reasons for culling were recorded by producers when female pigs were culled. Served month was categorized into four seasonal groups (January to March, April to June, July to September and October to December). Three WMI groups were formed: 0 to 6 days, 7 to 12 days and 13 days or more.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC). A linear mixed-effects model was applied to the two datasets using the MIXED procedure with a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test. Models 1 and 2 were applied to examine the association between production factors and lifetime performances in Dataset 1 (Model 1), or previous reproductive performance by parity groups in Dataset 2 (Model 2). These models included female groups (SRB or non-SRB females), the four seasonal service groups, the three herd productivity groups and entry year as fixed effects. A random herd effect was also included in both models. A chi-square test was conducted using SAS software to compare the relative frequency (%) of re-service intervals between SRB females and non-SRB females. Also, herd size was compared between the herd groups using ANOVA.

Models 3 and 4 were used to analyze service records for gilts and sows (Model 3) and sows only (Model 4) to determine whether or not a female pig was SRB (i.e., SRB risk per service). Models 3 and 4 were also used to account for the 3-level hierarchy of individual service records within a female and for females within a herd. The models were constructed by applying multilevel generalized linear models for SRB risks with a logit link function to Dataset 2 using MLwiN version 2.29 (University of Bristol, Bristol, UK). However, initial analyses showed that the estimated variances at the sow level were very close to zero (<0.0001). Therefore, the sow level was omitted from the models for the SRB risks [19, 20]. Parameter estimation was performed using the second-order penalized quasi-likelihood method and the iterative generalized least squares algorithm in MLwiN. The models contained the four seasonal service groups, the three herd productivity groups and entry year as fixed effects. Model 3 included AFM, whereas Model 4 contained sow specific factors such as the number of stillborn piglets, the three WMI groups and lactation length. All the continuous variables were centered at their grand mean values. Non-significant variables (P > 0.05) were eliminated from each model. The quadratic expressions of continuous variables were examined and non-significant quadratic expressions were removed (P ≥ 0.05). Random herd effect was also included in the models. The adequacy of the model assumptions for the random effects was assessed by visual inspection of normal-probability plots [21].

Intraclass correlation coefficient

The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated by the following equation [22] to assess the variance in SRB risk that could be explained by the herd:

ICC (records within the same herd) \( ={\sigma}_{\upnu}^2/\left({\sigma}_{\upnu}^2+\left({\pi}^2/3\right)\right) \), in which \( {\sigma}_{\upnu}^2 \) is the between-herd variance and π 2/3 is the variance at the assumed individual record level.

Results

Mean SRB risk per service (± SEM) was 0.26 ± 0.01% (Table 1). The SRB risks were greater in low parities, with 0.57 and 0.30% SRB risks for parity 0 and 1 females, respectively, compared with only 0.07–0.21% in parity 2 or higher sows (Table 2). The SRB female pigs had more regular returns than non-SRB female pigs (P < 0.05; Fig. 1) but the mean (± SEM) re-service interval for SRB females was 30.8 ± 0.31 days because 20% of SRB females had late re-service intervals of 39–150 days. Also, the proportions of SRB females having regular returns at the first, second and third re-service were 50, 57 and 59%, respectively (P < 0.05). Third returns occurred in 92% of the 98 herds. Larger herd size was associated with herd productivity groups; low-performing herds (Mean ± SEM: 482 ± 60 females) and intermediate herds (617 ± 83 females) had smaller herd sizes than high-performing herds (1095 ± 169 pigs; P < 0.01).

Relative frequencies (%) of re-service intervals for re-service records. a Re-service intervals for 5968 re-service records of severe repeat-breeder (SRB) females and 41,401 re-service records of non-SRB females. b Re-service intervals for 2469 first, 2008 s and 1491 third re-service records of SRB females

With regard to lifetime performance, 1150 (1.2%) of the 93,604 females became SRB pigs in their lifetime (Table 3). The SRB females had 3.0–4.3 fewer annualized lifetime pigs weaned, 14.4–16.4 fewer lifetime pigs born alive, 42.8–91.3 more lifetime NPD and 2.1–2.2 lower parities at culling than non-SRB females (P < 0.01; Table 3). Additionally, females that became SRB in parity 1 had 5.2% lower farrowing rates in their previous parity than non-SRB females (P < 0.01; Table 4). However, there was no difference between SRB and non-SRB female groups for WMI (P ≥ 0.07).

In both the first-served female (sows and gilts) model and the sows only model, an SRB risk was associated with low parity (i.e., parities 0 and 1), being first-served in summer and being fed in low-performing herds (P < 0.01; Table 5). Also, in the sows only model an SRB risk was associated with sows having prolonged WMI. For example, served gilts had 0.43 to 0.81% higher SRB risk than served sows (P < 0.01; Table 6). Additionally, females in a low-performing herd had 0.73 to 1.19% higher SRB risks than those in a high-performing herd. Also, the SRB risk of sows that had a WMI of 7–12 days was 0.10% higher than that of sows which had a shorter WMI of only 0–6 days (P < 0.05; Table 6). However, AFM (P = 0.08), lactation length (P = 0.05) and fewer stillborn piglets (P = 0.28) were not associated with being an SRB female. With regard to the ICC, the random herd effect explained 25.5% and 30.1% of total variance values for SRB risk in the female (gilts and sows) model and the sow only model, respectively (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study showed that one fifth of the 1.2% of first-served females that became RB pigs had re-service intervals of 39–150 days which would greatly increase NPD. Also, re-serving is one of the risk factors for abortion [13] and further increasing NPD. Re-service intervals and culling intervals account for 70% of NPD [4] which must be minimized to improve sow productivity. Additionally, the fact that SRB females had more regular re-service intervals (18–24 days) than non-SRB females indicates that SRB females are more likely to have either conception failure or failure of maternal recognition [8]. Other factors may also have contributed to the greater likelihood of SRB females having regular re-service, such as semen quality and storage [23], as well as timing of insemination [24].

In our study we found clear parity effects on the likelihood of females becoming SRB, with a higher risk in low parity females. One possible reason for the higher SRB risks in low parity females is that culling pressure for low parity females is not as high as that for aged sows, because gilts and parity 1 sows are still growing animals and producers want to recover the initial cost of a replacement gilt [5, 25]. Also, some sows with a reproductive problem may be culled before parity 2. Furthermore, recent data from Spanish, Portuguese and Italian herds showed that 41 and 36% of respective first-returned gilts and parity 1 sows had a return recurrence in the same or later parity [20]. Therefore, it is critical to have more accurate estrus detection and strict selection criteria for gilts in order to decrease both the number of SRB gilts and parity 1 sows and NPD in breeding herds. However, in our study low parity SRB females had shorter estrus duration than equivalent non-SRB females (Fig. 1), and it has also been reported that low parity females have subtle estrus behavior that is more difficult to detect [26]. Therefore, these differences in estrus characteristics make it difficult to identify the correct insemination timing in SRB females. One way to improve gilt development would be to include a boar stimulation protocol [27], which would help to distinguish between gilts that would become fertile females in breeding herds and those that are more likely to become SRB females.

In our study, females that were served in summer had a 0.1% higher SRB risk than those served in winter. Therefore, it appears that high temperature or low lactational feed intake in summer can increase conception failure or pregnancy loss in served females. Other research has also shown that parity 1 sows are more sensitive than parity 2 or higher sows to high temperature for increasing returns to re-service [8]. It has been suggested that a pregnancy loss in summer is related to a combination of low GnRH secretion, decreased LH release impaired ovarian follicle development and consequently degraded corpora lutea functions that produce low progesterone concentrations [28].

The WMI effect on sows becoming SRB could be related to low gonadotropin secretion and possibly impaired endocrine systems. For example, prolonged WMI in sows is thought to be due to low LH secretion caused by low feed intake during lactation [29]. Therefore, in this study we found that the main risk factors for SRB were low parity (0 or 1), being first-served in summer and having WMI 7–12 days. These findings are consistent with previous studies in the U.S.A., Sweden and Japan reporting a higher re-service risk associated with the same three factors [8, 10, 30].

We also found that herd productivity affected SRB risk. This result suggests that heat detection, pregnancy diagnosis, as well as culling policy and implementation were not good enough in the low-performing herds, probably because small-sized low-performing herds do not have sufficient resources for advanced production systems, sufficient gilt pool, equipment or professional workers. Also, herds with more SRB females will have decreased reproductive productivity and so would become low-performing herds. In contrast, large-sized high-performing herds are likely to be able to employ more skilled workers and have better facilities than small-to mid-sized low-performing herds [31]. Finally, the lack of any association in our study between SRB risks and either lactation length, AFM or the number of stillborn piglets indicates that SRB risks were not greatly influenced by these factors in the studied herds.

Regarding lifetime reproductive performance, the fact that SRB females had 90 more NPD than non-SRB females suggests that producers’ culling guidelines were not strictly implemented for returned females in the studied herds. Keeping SRB females too long in a herd increases NPD and decreases efficiency of the sows, because the SRB females produce pigs 30% (21.4/ 27.6 annualized lifetime pigs born alive) less efficiently than non-SRB females, and their mean re-service interval of 55 days increase NPD.

The present study shows that low parity SRB sows had a lower farrowing rate in their previous parity than non-SRB sows in the same parity. It is likely that some of the low parity SRB sows had a latent reproductive problem that caused them to have a lower farrowing rate in the earlier parity, even though it had not yet become serious enough for them to require a re-service. One possible reproductive problem in low parity sows is ovary cysts, and a recent study reported that sows with ovary cysts had 20% more returns to estrus than sows without ovary cysts [32]. In contrast, the lack of any difference between parity 1 or higher SRB and non-SRB sows for farrowing rate and WMI sows indicates that the reason that the sows in parity 1 or higher became SRB was due to problems such as lactation and post weaning period. Finally, in the present study, the relatively high ICC for herd variance of 25.5% for the gilts and sows model and 30.1% for the sows only model indicates that there was a substantial effect of the herds on SRB, for example due to differences in heat detection programs or culling policy.

There are some limitations that should be noted when interpreting the results of the present study. This was an observational study performed using commercial herd data. Health status, nutritional programs, genotype, semen quality, proportions of double and triple inseminations, cysts and early or late abortion were not considered in the analyses. However, even with such limitations, this research provides valuable information for pig producers and veterinarians about SRB females in commercial herds, and the relationships between the risk of having SRB females and production factors.

Finally, our definition of SRB pigs is different from previous reports about repeat-breeding which sometimes is defined as one return [5, 6] and sometimes as one to four returns [7]. In our study, the objective was to examine severe repeat-breeder females, so we defined SRB females as having three or more returns in the same parity.

Conclusions

We recommend that producers closely monitor high risk female groups to reduce their returns-to-service. The high risk groups include mated gilts and parity 1 sows, females being served in summer, and females having prolonged WMI, especially those in low performing herds.

Abbreviations

- NPD:

-

Non-productive days

- AFM:

-

Gilt age at first-mating

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficients

- SRB:

-

Severe repeat-breeder

- WMI:

-

Weaning-to-first-mating interval

References

PigCHAMP. PigCHAMP benchmarks. 2015.http://www.pigchamp.com/Portals/0/Documents/Benchmarking%20Summaries/USA%202015.pdf. Accessed 15 Jun 2016.

Koketsu Y. Re-serviced females on commercial swine breeding farms. J Vet Med Sci. 2003;65:1287–91.

Sasaki Y, Koketsu Y. A herd management survey on culling guidelines and actual culling practices in three herd groups based on reproductive productivity in Japanese commercial swine herds. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:1995–2002.

Koketsu Y. Six component intervals of nonproductive days by breeding-female pigs on commercial farms. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:1406–12.

Vargas AJ, Bernardi ML, Paranhos TF, Gonçalves MA, Bortolozzo FP, Wentz I. Reproductive performance of swine females re-serviced after return to estrus or abortion. Anim Reprod Sci. 2009;113:305–10.

Horvat G, Bilkei G. Exogenous prostaglandin F2α at time of ovulation improves reproductive efficiency in repeat breeder sows. Theriogenology. 2003;59:1479–84.

Kauffold J, Melzer F, Berndt A, Hoffmann G, Hotzel H, Sachse K. Chlamydiae in oviducts and uteri of repeat breeder pigs. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1816–23.

Iida R, Koketsu Y. Interactions between climatic and production factors on returns of female pigs to service during summer in Japanese commercial breeding herds. Theriogenology. 2013;80:487–93.

Tummaruk P, Lundeheim N, Einarsson S, Dalin A-M. Effect of birth litter size, birth parity number, growth rate, backfat thickness and age at first mating of gilts on their reproductive performance as sows. Anim Reprod Sci. 2001;66:225–37.

Tummaruk P, Tantasuparuk W, Techakumphu M, Kunavongkrit A. Influence of repeat-service and weaning-to-first-service interval on farrowing proportion of gilts and sows. Prev Vet Med. 2010;96:194–200.

Bloemhof S, Mathur PK, Knol EF, van der Waaij EH. Effect of daily environmental temperature on farrowing rate and total born in dam line sows. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:2667–79.

Iida R, Koketsu Y. Lower farrowing rate in female pigs associated with higher outdoor temperatures in humid subtropical and continental climate zones in Japan. Anim Reprod. 2016;13:63–8.

Iida R, Koketsu Y. Climatic factors associated with abortion occurrences in Japanese commercial pig herds. Anim Reprod Sci. 2015;157:78–86.

European commission. Pig: number of farms and heads by agricultural size of farm (UAA) and size of pig herd, 2016. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do. Aaccessed 30 Dec 2016.

Lundgren H, Canario L, Grandinson K, Lundeheim N, Zumbach B, Vangen O, et al. Genetic analysis of reproductive performance in Landrace sows and its correlation to piglet growth. Livest Sci. 2010;128:173–8.

Hoving L, Soede N, Graat E, Feitsma H, Kemp B. Reproductive performance of second parity sows: Relations with subsequent reproduction. Livest Sci. 2011;140:124–30.

Ferreira R, Ayres H, Chiaratti M, Ferraz M, Araújo A, Rodrigues C, et al. The low fertility of repeat-breeder cows during summer heat stress is related to a low oocyte competence to develop into blastocysts. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94:2383–92.

Koketsu Y, Tani S, Iida R. Factors for improving reproductive performance of sows and herd productivity in commercial breeding herd. Porcine Health Manag. 2017;3:1.

Vigre H, Dohoo IR, Stryhn H, Busch ME. Intra-unit correlations in seroconversion to Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at different levels in Danish multi-site pig production facilities. Prev Vet Med. 2004;63:9–28.

Tani S, Piñeiro C, Koketsu Y. Recurrence patterns and factors associated with regular, irregular, and late return to service of female pigs and their lifetime performance on southern European farms. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:1924–32.

Rasbash J, Steele F, Browne WJ, Goldstein H. A User’s Guide to MLwiN Version 2.26. UK: University of Bristol; 2012.

Dohoo IR, Martin SW, Stryhn H. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. 2nd ed. Charlottetown: VER Inc.; 2009.

Nutthee A, Tantasuparuk W, Manjarin R, Kirkwood RN. Effect of site of sperm deposition on fertility when sows are inseminated with aged semen. J Swine Health Prod. 2011;19(5):295–7.

Soede NM, Wetzels CCH, Zondag W, de Koning MAI, Kemp B. Effects of time of insemination relative to ovulation, as determined by ultrasonography, on fertilization rate and accessory sperm count in sows. J Reprod Fertil. 1995;104:99–106.

Sasaki Y, Koketsu Y. Reproductive profile and lifetime efficiency of female pigs by culling reason in high-performing commercial breeding herds. J Swine Health Prod. 2011;19:284–91.

Steverink D, Soede N, Groenland G, Van Schie F, Noordhuizen J, Kemp B. Duration of estrus in relation to reproduction results in pigs on commercial farms. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:801–9.

Patterson JL, Beltranena E, Foxcroft GR. The effect of gilt age at first estrus and breeding on third estrus on sow body weight changes and long-term reproductive performance. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:2500–13.

Bertoldo MJ, Holyoake PK, Evans G, Grupen CG. Seasonal variation in the ovarian function of sows. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2012;24:822–34.

Koketsu Y, Dial GD, Pettigrew JE, Marsh WE, King VL. Influence of imposed feed intake patterns during lactation on reproductive performance and on circulating levels of glucose, insulin, and luteinizing hormone in primiparous sows. J Anim Sci. 1996;74:1036–46.

Koketsu Y, Dial GD, King VL. Returns to service after mating and removal of sows for reproductive reasons from commercial swine farms. Theriogenology. 1997;47:1347–63.

King VL, Koketsu Y, Reeves D, Xue JL, Dial GD. Management factors associated with swine breeding-herd productivity in the United States. Prev Vet Med. 1998;35:255–64.

Castagna CD, Peixoto CH, Bortolozzo FP. Wentz I, Neto GB, Ruschel Fc. Ovarian cysts and their consequences on the reproductive performance of swine herds. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;81:115–23.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the swine producers for their cooperation in providing their valuable data for use in this study. We also thank Dr. I. McTaggart for his critical review of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Grant Kiban-A (2012–2016) and Graduate School GP-2016 from Meiji University.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analyzed during the current study is not publicly available because producers’ privacy could be compromised.

Authors’ contributions

ST and YK were responsible for the study design. CP was responsible for data acquisition and participated in the study design. ST carried out the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tani, S., Piñeiro, C. & Koketsu, Y. Characteristics and risk factors for severe repeat-breeder female pigs and their lifetime performance in commercial breeding herds. Porc Health Manag 3, 12 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-017-0059-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-017-0059-0