Abstract

Background

The ACTN3 gene may influence performance in team sports, in which sprint action and high-speed movements, regulated by the anaerobic energy system, are crucial to the ultimate success of a match. The aim of this study was to determine the association between the ACTN3 R577X (rs1815739) polymorphism and elite team sport athletic status in Italian male athletes.

Methods

We compared the genotype and allele frequency of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism between team sport athletes (n = 75), endurance athletes (n = 40), sprint/power athletes (n = 64), and non-athletic healthy controls (n = 192) from Italy. Genomic DNA was collected using a buccal swab. Extraction was performed according to the manufacturer’s directions provided with a commercially available kit (Qiagen S.r.l., Milan, Italy).

Results

Team sport athletes showed a lower frequency of the 577RR genotype compared to the 577XX genotype than sprint/power athletes (p = 0.044). However, the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism was not associated with team sport athletic status compared to endurance athletes and non-athletic controls.

Conclusions

Our results agree with a recent large-scale study involving athletes from Spain, Poland, and Russia. The ACTN3 R577X polymorphism was not associated with team sport athletic status compared to endurance athletes and non-athletic controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

The study showed that the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism is not considered a candidate gene to influence the performance of team sport athletes, yet we confirmed that the ACTN3 577RR genotype is overrepresented in sprint/power athletes compared to those in team sports.

-

As result, this study emphasizes the importance of considering well-defined groups of athletes with a clear reference phenotype in genetic association studies applied to elite sport performance, also suggesting possible inter-individual genetic differences between athletes in the same team sport.

Background

Research in the field of genetics among elite athletic performers has focused primarily on the sport at the end point of the sports performance continuum (sprint/power vs. endurance performance), yet the type of sport in which both the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems are important for achieving a high level of performance, such as team sports or endurance sports, has received little attention.

One of the most common targets of investigation has been a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the ACTN3 gene, which encodes the alpha-actinin-3 protein [1]. This polymorphism leads to a premature stop codon (X), rather than an arginine (R) at position 577. Alpha-actinin-3 deficiency (ACTN3 577XX genotype) occurs in approximately 16% of the global population [1] and is associated with variations in human muscle performance. The alpha-actinin-3 protein is almost exclusively expressed in fast, glycolytic, and type IIX fibers that are responsible for the generation of rapid forceful contractions during activities such as sprinting.

Meta-analyses [2,3] and a recent review [4] of the literature regarding the influence of ACTN3 on athletic performance suggest that the ACTN3 577RR genotype is associated with sprint/power athletes among Caucasians. Recently, Mikami et al. [5] examined a large cohort of elite Japanese athletes (n = 299) and found that the ACTN3 R577X genotype was associated with sprint/power performance among track and field competitors, especially running 100- to 200-m sprints, and that R allele was associated with relative peak power in male collegiate athletes [6]. On the contrary, a recent study of Caucasian and East Asian swimmers did not show an association between ACTN3 polymorphism and elite swimmer status [7]. The ACTN3 577X allele and the 577XX genotype were significantly associated with only certain groups of elite endurance athletes [8-17].

Seto et al. [18] provided a mechanistic explanation for the effects of the ACTN3 genotype on skeletal muscle performance in elite athletes and on adaptation to changing physical demands in the general population. The authors highlighted the emerging evidence of the roles of alpha-actinin-3 in the regulation of metabolic and signaling pathways, contractile properties, and muscle fiber type. They showed that alpha-actinin-3 deficiency resulted in increased calcineurin activity in mouse and human skeletal muscle and an enhanced adaptive response to endurance training. Only a few studies investigated the association between the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and team sport performance. Santiago et al. [19] examined the frequency of this ACTN3 genotype in 60 top-level professional Spanish soccer players, showing that the percentage distributions of 577RR and 577RX genotypes (48.3% and 36.7%) were significantly higher and lower, respectively, than those in controls (n = 123; 28.5% and 53.7%) or endurance athletes (n = 52; 26.5% and 52%) (p = 0.041). In a previous study [20], we did not find a significant difference in top-level soccer players’ (n = 42) jump performance among the various genotypes.

Pimenta et al. [21] examined 200 Brazilian professional soccer players and found that 577RR carriers ran 10, 20, and 30 m faster than 577XX carriers. Furthermore, the former scored higher in jump tests compared to both 577RX and 577XX carriers.

Not all the studies, however, found an association between ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and team sport performance [22-24]. Recently, Garatachea et al. [25] did not find an association between ACTN3 genotypes and explosive leg power in elite basketball players or with the status of being this type of athlete. Finally, Eynon et al. [26] compared the genotype and allele frequencies of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphisms in a relatively large cohort of team sport athletes (n = 205), endurance athletes (n = 305), sprint/power athletes (n = 378), and non-athletic controls (n = 568) from Europe and found that ACTN3 R577X polymorphism was not associated with team sport athletic status. However, they did find that the 577RR genotype was overrepresented in sprint/power athletes compared to team sport athletes.

The aim of this study was to analyze the associations between ACTN3 R577X polymorphisms and elite team sport athletic status in a group of Italian athletes and to compare their genotype distributions with elite sprint/power athletes, endurance athletes, and non-athletic controls.

Methods

A total of 178 Italian male athletes (n = 74 team sport athletes, n = 64 sprint/power athletes, n = 40 endurance athletes) and 190 controls were recruited between 2004 and 2014. All participants were unrelated European men, and all had Caucasian lineage for at least three generations. According to individual best performances, the athletes were divided into two subgroups: ‘elite level’ (competitors in European/World Championships or in the Olympic Games) and ‘national level’ (competitors in national-level but not international-level events) (Table 1). Of the athletes, 101 (57%) were classified as elite level and the remaining 77 (43%) were classified as national level.

-

(i)

The team sport athletes (n = 74) included 64 soccer players and 10 hockey players. Of these, 8 hockey players competed at international level (World/European Championships), 20 soccer players competed at international level (including five World Championships), while 2 hockey players and 44 soccer players competed at the national level (Italian Professional Championships, ‘Serie A’).

-

(ii)

The sprint/power athletes (n = 64) included 16 track and field sprinters, 1 sprint swimmer, 17 wrestlers, 11 power lifters, and 19 gymnasts. Of these, 11 sprinters, 1 swimmer, 4 wrestlers, 10 power lifters, and 17 gymnasts were in the elite-level group, while 5 sprinters, 13 wrestlers, 1 power lifter, and 2 gymnasts were in the national-level group.

-

(iii)

The endurance athletes (n = 40) included 24 track and field long-distance runners and 16 triathletes. Of these, 15 triathletes were in the elite-level group while all runners and 1 triathlete was in the national-level group.

The genotype frequencies among these athletes were compared with those of the randomly selected healthy non-athletic Italian males (controls). The controls were selected if they did not participate regularly in any competitive or structured sport or physical activity.

All participants and their parent/guardian (for minors) provided written informed consent, and the study protocol and informed written consent procedure were approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the Italian Sports Federations, in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki for Human Research of 1974 (last modified in 2000).

Genomic DNA was extracted from each athlete with a buccal swab during the years 2004 to 2014, according to the manufacturer’s directions provided with a commercially available kit (Qiagen S.r.l., Milan, Italy) [27]. Exon 16 of ACTN3 was amplified through polymerase chain reaction using the following primers:

forward 5′-CTGTTGCCTGTGGTAAGTGGG-3′

reverse 5′-TGGTCACAGTATGCAGGAGGG-3′.

Polymerase chain reaction products were digested with DdeI enzyme. The 577R and 577X alleles (CGA and TGA codons, respectively) were distinguished by the presence (577X) or absence (577R) of a DdeI restriction site in exon 16. Allele 577X shows two fragments with 205 and 85 bp, while allele 557R presents three fragments with 108, 97, and 86 bp. The obtained fragments were separated by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide [27]. To ensure proper internal control, for each genotype analysis, we used positive and negative controls from different DNA aliquots that were previously genotyped with the same method.

Chi-squared tests were used to test for the presence of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the association between genotype and athletic status/competition level. In each case, analyses were made comparing 577XX (reference group) vs. 577RX, 577XX vs. 577RR (co-dominant effect), 577XX vs. 577RR and 577RX combined (dominant effect), and 577XX and 577RX combined (reference group) vs. 577RR (recessive effect). Significance was accepted when p ≤ 0.05. Chi-squared tests for HWE were conducted using Genepop (v. 9), while statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA (Statsoft v. 7)

Results

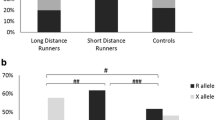

Table 1 shows the genotype and allele frequency distributions in the non-athletes and athletes divided by group and subgroup. The genotype distributions met HWE (all p > 0.05) for all groups of participants.

Our data showed significant differences in genotype frequency between team sport athletes and sprinters (Table 2). Team sport athletes had a lower frequency of the 577RR genotype compared to the 577XX genotype than the sprint/power athletes (p = 0.044) (Table 2). In fact, the sprint/power athletes were approximately 1.5 times more likely to have the 577RR genotype (as opposed to the 577XX genotype) than team sport athletes. No association was observed for any of the genotypes with respect to the level of competition (elite vs. national level) (Table 3).

Discussion

We tested, for the first time, the association between ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and team sport athletic status in Italian athletes. Our results indicate that team sport athletes have a lower 577RR than 577XX genotype frequency, compared to sprint/power athletes (p = 0.044). No significant difference in the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism genotype distribution was found between the team sport athletes, endurance athletes, and control group. Furthermore, the ACTN3 R577X genotype distribution was similar between elite-level and national-level team sport athletes, suggesting that this polymorphism is not influential among team sport athletes.

Our findings agree with those of Eynon et al. [26], who recently analyzed elite team sport athletes from three European countries (i.e., Spain, Poland, and Russia) and showed that their performance was not significantly influenced by ACTN3 R577X polymorphism. Similarly, our results agree with theirs in that team sport athletes were less likely to possess the 577RR genotype than the 577XX genotype compared to power athletes (p = 0.045).

The ACTN3 R577X polymorphism was consistently associated with elite sprint/power status [2,3] and muscle power [6]. The functional consequence of the ACTN3 R577X polymorphisms on sport performance is supported by the Actn3 knock-out (KO) mouse model [28]. The authors demonstrated that the loss of alpha-actinin expression results in a shift in muscle metabolism toward the more efficient aerobic pathway, with a subsequent increase in running distance achieved before exhaustion during a treadmill test [28]. Moreover, the Actn3 KO mice (ACTN3 577XX), compared to wild-type (WT) counterparts, had lower muscle mass (smaller diameter fast-twitch muscle fibers), significantly lesser grip strength, significantly lower anaerobic enzyme activity, and higher oxidative/mitochondrial enzyme activity without a shift in fiber-type distribution [29].

In team sports, most of the decisive actions during competition are characterized by jumping and/or sprinting, and it is for that reason that we hypothesized that the 577RR genotype would be associated with team sport performance. However, team sports generally involve mixed aerobic-anaerobic demands and players may not need to have extraordinary aerobic/anaerobic capacity. During a soccer game, for example, aerobic metabolism dominates energy delivery [30], yet the most decisive actions, characterized by jumping and sprinting, are supported by anaerobic metabolism. In similar team sports, many factors contribute to success, including muscle power, aerobic endurance, ball skills, and psychological traits. Therefore, muscle power represents just one of several factors that determine a player’s ability but a substantial development of this factor is decisive during the crucial phases of a match.

When studying the possible role of genetics in team sports, it should be noted that not all players have similar characteristics in terms of physiological demand because it varies based on the position played. For example, during a rugby match, players perform various activities based on their position [31]. Forwards, rather than backs, are involved in significantly more physical collisions and tackles, experience a greater proportion of high-intensity activity than low-intensity activity, and travel greater distances during a match (9,929 vs. 8458 m) [31], demonstrating that a wide range of skills and physiological demands exist for the different playing positions.

Indeed, while ACTN3 R577X polymorphism has been previously associated with sprint/power or endurance performance, the results of this study suggest that it is not associated with team sport athletic status.

The most obvious limitation of this study is the sample size. However, the very large population samples required to reach a sufficient statistical power in the field of genetic studies do not harmonize with the limited number of elite athletes for each sport discipline. We believe that the small sample size could be justifiable by the number of top-level athletes and by the homogeneity of the sample in terms of geographical and ethnical origin, recruited for the present study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results confirm, for the Italian population, the recent data published by Eynon et al. [26] that ACTN3 R577X polymorphism is not significantly associated with team sport athletic status, when team sport athletes are compared to endurance athletes and non-athletic controls, and the 577RR genotype is overrepresented in power/sprint athletes compared to team sport athletes.

References

North KN, Yang N, Wattanasirichaigoon D, Mills M, Easteal S, Beggs AH, et al. A common nonsense mutation results in alpha-actinin-3 deficiency in the general population. Nat Genet. 1999;21(4):353–4.

Alfred T, Ben-Shlomo Y, Cooper R, et al. ACTN3 genotype, athletic status, and life course physical capability: meta-analysis of the published literature and findings from nine studies. Hum Mutat. 2011;32(9):1008–18.

Ma F, Yang Y, Li X, Hardy R, Cooper C, Deary IJ, et al. The association of sport performance with ACE and ACTN3 genetic polymorphisms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54685.

Eynon N, Hanson ED, Lucia A, Houweling PJ, Garton F, North KN, et al. Genes for elite power and sprint performance: ACTN3 leads the way. Sports Med. 2013;43(9):803–17.

Mikami E, Fuku N, Murakami H, et al. ACTN3 R577X genotype is associated with sprinting in elite Japanese athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35(2):172–7.

Kikuchi N, Nakazato K, Min SK, Tsuchie H, Takahashi H, Ohiwa N, et al. The ACTN3 R577X polymorphisms is associated with muscle power in male Japanese athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(7):1783-9.

Wang G, Mikami E, Chiu LL, DE Perini A, Deason M, Fuku N, et al. Association analysis of ACE and ACTN3 in elite Caucasian and East Asian swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(5):892–900.

Yang N, MacArthur DG, Gulbin JP, Hahn AG, Beggs AH, Easteal S, et al. ACTN3 genotype is associated with human elite athletic performance. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(3):627–31.

Eynon N, Duarte JA, Oliveira J, Sagiv M, Yamin C, Meckel Y, et al. ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and Israeli top-level athletes. Int J Sports Med. 2009;30(9):695–8.

Niemi AK, Majamaa K. Mitochondrial DNA and ACTN3 genotypes in Finnish elite endurance and sprint athletes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(8):965–9.

Doring FE, Onur S, Geisen U, Boulay MR, Pérusse L, Rankinen T, et al. ACTN3 R577X and other polymorphisms are not associated with elite endurance athlete status in the Genathlete study. J Sports Sci. 2010;28(12):1355–9.

Muniesa CA, González-Freire M, Santiago C, Lao JI, Buxens A, Rubio JC, et al. World-class performance in lightweight rowing: is it genetically influenced? A comparison with cyclists, runners and non-athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(12):898–901.

Saunders CJ, September AV, Xenophontos SL, Cariolou MA, Anastassiades LC, Noakes TD, et al. No association of the ACTN3 gene R577X polymorphism with endurance performance in Ironman Triathlons. Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71(Pt 6):777–81.

Scott RA, Irving R, Irwin L, Morrison E, Charlton V, Austin K, et al. ACTN3 and ACE genotypes in elite Jamaican and US sprinters. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(1):107–12.

Ruiz JR, Fernández del Valle M, Verde Z, Díez-Vega I, Santiago C, Yvert T, et al. ACTN3 R577X polymorphism does not influence explosive leg muscle power in elite volleyball players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(6):e34–41.

Shang X, Huang C, Chang Q, Zhang L, Huang T. Association between the ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and female endurance athletes in China. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:913–6.

Yang N, MacArthur DG, Wolde B, Onywera VO, Boit MK, Lau SY, et al. The ACTN3 R577X polymorphism in East and West African athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(11):1985–8.

Seto JT, Quinlan KGR, Lek M, Zheng XF, Garton F, MacArthur DG, et al. ACTN3 genotype influences muscle performance through the regulation of calcineurin signaling. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4255–63.

Santiago C, Gonzalez-Freire M, Serratosa L, Morate FJ, Meyer T, Gómez-Gallego F, et al. ACTN3 genotype in professional soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(1):71–3.

Massidda M, Corrias L, Ibba G, Scorcu M, Vona G, Calò CM, et al. Genetic markers and explosive leg-muscle strength in elite Italian soccer players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2012;52(3):328–34.

Pimenta EM, Coelho DB, Veneroso CE, Barros Coelho EJ, Cruz IR, Morandi RF, et al. Effect of ACTN3 gene on strength and endurance in soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(12):3286–92.

Ginevičienė V, Pranculis A, Jakaitienė A, Milašius K, Kučinskas V. Genetic variation of the human ACE and ACTN3 genes and their association with functional muscle properties in Lithuanian elite athletes. Medicina (Mex). 2011;47(5):284–90.

Bell W, Colley JP, Evans WD, Darlington SE, Cooper SM. ACTN3 genotypes of Rugby Union players: distribution, power output and body composition. Ann Hum Biol. 2012;39(1):19–27.

Sessa F, Chetta M, Petito A, Franzetti M, Bafunno V, Pisanelli D, et al. Gene polymorphisms and sport attitude in Italian athletes. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15(4):285–90.

Garatachea N, Verde Z, Santos-Lozano A, Yvert T, Rodriguez-Romo G, Sarasa FJ, et al. ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and explosive leg-muscle power in elite basketball players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9(2):226–32.

Eynon N, Banting LK, Ruiz JR, Cieszczyk P, Dyatlov DA, Maciejewska-Karlowska A, et al. ACTN3 R577X polymorphism and team-sport performance: a study involving three European cohorts. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(1):102–6.

Mills M, Yang N, Weinberger R, Vander Woude DL, Beggs AH, Easteal S, et al. Differential expression of the actin-binding proteins, a-actinin-2 and -3, in different species: implications for the evolution of functional redundancy. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(13):1335–46.

MacArthur DG, Seto JT, Raftery JM, Quinlan KG, Huttley GA, Hook JW, et al. Loss of ACTN3 gene function alters mouse muscle metabolism and shows evidence of positive selection in humans. Nat Genet. 2007;39(10):1261–5.

MacArthur DG, Seto JT, Chan S, Quinlan KG, Raftery JM, Turner N, et al. An Actn3 knockout mouse provides mechanistic insights into the association between alpha-actinin-3 deficiency and human athletic performance. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(8):1076–86.

Bangsbo J, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(7):665–74.

Meir R, Colla P, Milligan C. Impact of the 10-meter rule change on professional rugby league: implications for training. Strength Condit J. 2001;23:42–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the staff and athletes within the Italian Sports Federations and Cagliari Calcio Spa who participated in the study and who assisted with data collection. The authors are also grateful to Selvin Squire for English editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MM conceived of the study, participated in its design, performed statistical analysis, interpretated the results and wrote the manuscript. VB carried out the laboratory analyses. LC carried out the laboratory analyses. FP partecipated in data collection. MS partecipated in the sample selection and data collection. CC carried out the laboratory analyses. DM partecipated in the sample selection and data collection. CMC participated in the study design and its coordination, critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Massidda, M., Bachis, V., Corrias, L. et al. ACTN3 R577X polymorphism is not associated with team sport athletic status in Italians. Sports Med - Open 1, 6 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-015-0008-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-015-0008-x