Abstract

Background

Rivers and streams are important components of the global carbon cycle and methane budget. However, our understanding of the microbial diversity and the metabolic pathways underpinning methylotrophic methane production in river sediments is limited. Dimethylsulfide is an important methylated compound, found in freshwater sediments. Yet, the magnitude of DMS-dependent methanogenesis nor the methanogens carrying out this process in river sediments have been explored before. This study addressed this knowledge gap in DMS-dependent methanogenesis in gravel and sandy river sediments.

Results

Significant methane production via DMS degradation was found in all sediment microcosms. Sandy, less permeable river sediments had higher methane yields (83 and 92%) than gravel, permeable sediments (40 and 48%). There was no significant difference between the methanogen diversity in DMS-amended gravel and sandy sediment microcosms, which Methanomethylovorans dominated. Metagenomics data analysis also showed the dominance of Methanomethylovorans and Methanosarcina. DMS-specific methyltransferase genes (mts) were found in very low relative abundances whilst the methanol-, trimethylamine- and dimethylamine-specific methyltransferase genes (mtaA, mttB and mtbB) had the highest relative abundances, suggesting their involvement in DMS-dependent methanogenesis.

Conclusions

This is the first study demonstrating a significant potential for DMS-dependent methanogenesis in river sediments with contrasting geologies. Methanomethylovorans were the dominant methylotrophic methanogen in all river sediment microcosms. Methyltransferases specific to methylotrophic substrates other than DMS are likely key enzymes in DMS-dependent methanogenesis, highlighting their versatility and importance in the methane cycle in freshwater sediments, which would warrant further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Freshwater ecosystems such as lakes, rivers and streams are important components of the global carbon cycle. These ecosystems account for around half of the methane emitted to the atmosphere (538–884 Tg y−1), contributing considerably to the global greenhouse gas budget [53]. In particular, rivers were estimated to emit 27.9 Tg methane per year despite accounting for around 0.58% of the Earth’s non-glaciated surface area [1, 52]. Since the importance of rivers for global methane emissions has only recently been acknowledged, studies on methane production pathways and underlying microbial populations in the river sediments are scarce, impeding progress in projecting global greenhouse gas emissions.

Recent studies suggest a strong influence of climatic factors, adjacent soil characteristics (e.g. organic carbon stock, groundwater table depth and primary production) and geomorphological variables (e.g. sediment properties, river slope and elevation) on methane production and emission rates from river ecosystems [52]. Among the physical factors affecting methane production is the sediment grain size, which may substantially alter the sediment permeability, organic and inorganic matter content and sediment oxygen concentrations [19, 22, 26, 37, 52]. For instance, sandy riverbeds are less permeable than gravel riverbeds and are most likely to contain anoxic zones, where methane production can be observed [3, 24, 31, 59, 66].

Methanogenesis in river sediments has mainly been attributed to the hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic pathways; however, methanogenesis through the degradation of methylated compounds such as methanol and dimethylsulfide (DMS) was also shown in freshwater ecosystems [38, 38, 39, 39, 40]. In freshwater sediments, the degradation of sulfur-containing aminoacids and methoxylated aromatic compounds as well as methanethiol methylation and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) reduction results in DMS production [55, 56]. However, DMS degradation was only studied in freshwater peatland and lake sediments [15, 38, 39]. More recently, we have demonstrated that as much as 41% of DMS amended to the River Medway (UK) sediments were anaerobically degraded to methane, likely contributing to the in situ methane production in this river sediment [68].

Methanogen populations undertaking anaerobic DMS degradation and their metabolic pathways are poorly characterised. A limited number of species from the genera Methanomethylovorans, Methanolobus, Methanosarcina and Methanohalophilus were isolated from freshwater and saline ecosystems as DMS-degrading methanogens [16, 25, 36, 38, 39, 42, 45, 47]. Further, methylthiol:coenzyme M methyltransferase (Mts) was shown to catalyse the formation of methane from DMS in Methanosarcina strains [18, 46, 63]. Our recent study has also shown the involvement of methanol- and trimethylamine-methyltransferases in anaerobic DMS degradation in brackish sediments [67]. Yet, we do not know whether these represent the dominant DMS-degrading methanogen populations and key genes in this process in river sediments.

We hypothesised that DMS may be an important methane precursor in river sediments, which may harbour different methylotrophic methanogen populations based on grain size and permeability. We tested this hypothesis by quantifying the extent of DMS-dependent methanogenesis in river sediments with contrasting grain sizes and characterising the methanogen diversity driving this process. We also provided the first insight into the potential metabolic pathways of DMS-dependent methane production in river sediments.

Methods

Site characteristics and sediment sampling

Three sediment cores (3.5 cm Ø) were collected from each sampling site in the UK in February 2019 (Rivers Pant and Rib) and in March 2021 (Rivers Medway and Nadder; Fig. 1) to set up microcosms. Approximately 1 L of sediment from the top 5 cm were also collected from the sites and were screened through 2 mm and 0.0625 mm sieves to characterise the sediment as gravel (sediment size > 2 mm) or sandy (2 mm < sediment size < 0.0625 mm; Supplementary Table 1; [73]).

Microcosm set-up

Five replicated microcosms were set up per sampling site in 140 mL serum bottles (Wheaton, USA) in an anaerobic glove box (Belle Technology, UK). We mixed the sediment from the three cores (depth 4–10 cm) and used 5 g of homogenised sediment and 40 mL of growth medium (pH 7), which contained 3.2 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 0.088 mM NaNO3, 0.031 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 0.1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 0.9 mM Trizma base, 2.1 µM K2HPO4.3H2O, trace elements, and vitamins [76, 77]. The trace element solution was prepared according to DMSZ media 141 and modified to contain FeC6H6O7 (5 g) instead of N(CH2CO2H)3 and no Na2WO4·2 H2O.

Samples were initially amended with 2 µmol DMS g−1 wet sediment through gas-tight glass syringes as the only energy and carbon source. After the first DMS addition was depleted, 4 µmol DMS g−1 wet sediment was added in each subsequent amendment to avoid DMS toxicity. A total of 43–154 µmol DMS g−1 sediment was consumed by the end of the incubation period. Two sets of controls (three replicates per each set) were also established. One set contained no DMS and the second set contained thrice autoclaved sediment with DMS to monitor the DMS adsorption by sediment. All microcosm bottles were kept at 22 °C and in the dark to avoid photochemical destruction [7].

Analytical measurements

Headspace DMS in the microcosm bottles was measured using a gas chromatograph (GC; Agilent Technologies, 6890A Series, USA) fitted with a flame photometric detector (FPD) and a J&W DB-1 column (30 m × 0.32 mm Ø; Agilent Technologies, USA). The oven temperature was set at 180 °C, and zero grade N2 (BOC, UK) was used as the carrier gas (26.7 mL min−1). FPD run at 250 °C with H2 and air (BOC, UK) at a flow rate of 40 and 60 mL min−1, respectively. DMS standards were prepared by diluting > 99% DMS (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in distilled water previously made anaerobic with oxygen-free N2 (BOC, UK).

Methane and carbon dioxide (CO2) were measured using a GC (Agilent Technologies, USA, 6890N Series) fitted with a flame ionisation detector (FID), Porapak (Q 80/100) packed stainless steel column (1.83 m × 3.18 mm Ø; Supelco, USA), and hot-nickel catalyst, which reduced CO2 to methane (Agilent Technologies, USA; [54]). The oven temperature was set at 30 °C, and zero grade N2 (BOC, UK) was used as the carrier gas (14 mL min−1). FID run at 300 °C with H2 and air (BOC, UK) at a flow rate of 40 and 430 mL min−1, respectively. Certified gas mixture was used as standards (100 ppm methane, 3700 ppm CO2, 100 ppm N2O, balance N2; BOC, UK). All methane concentrations were corrected for the headspace-water partitioning using Henry’s law to calculate the total methane.

The total production of CO2 was the sum of the change of CO2 in the headspace and the total dissolved inorganic carbon (ΣDIC = CO2 + HCO3− + CO32−) in the water phase. For the ΣDIC, 3 mL of supernatant from each microcosm was collected in 3 mL gas-tight vials (Exetainer, Labco, UK) and fixed using 24 µL ZnCl2 (50% w/v). 100 µL of 35% HCl was added to acidify the samples and CO2 in the headspace was measured. An inorganic calibration series (0.1–8 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) of Na2CO3 was used as standard [58].

Methane and CO2 concentrations in the control bottles were between 0.45–20 µmol/g and 0.035–1.95 µmol/g, respectively. These values were subtracted from the concentrations measured in DMS-amended microcosms.

Sequencing library preparation and sequence data analysis

DNA was collected from the bottles at the end of the incubation period and was extracted from 0.25 g sediment using the DNeasy Powersoil kit (Qiagen, NL) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The mcrA gene, which encodes the α-subunit of the methylcoenzyme M reductase from all known methanogens, was used as the methanogen molecular marker. The mcrA gene in each replicated microcosm was first amplified using the mcrIRD primer set [32] and a second PCR was carried out using the same primer set with overhang adapters as was described in Tsola et al. [68]. PCR products were further amplified to add dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters. All PCR products were cleaned using JetSeq Clean beads (1.4x; Meridian Bioscience, USA), normalized using the SequalPrep Normalization Plate kit (Invitrogen, USA) and sequenced at 2 × 300 bp Illumina MiSeq Next Generation sequencing platform.

The sequence analysis was performed using QIIME2 2021.11 on Queen Mary’s Apocrita HPC facility, supported by QMUL Research-IT [5, 30]. Taxonomy was assigned to the ASVs using Naive Bayes classifiers, trained using the feature-classifier command in QIIME2 [4] and a custom-made mcrA database. These databases were prepared using FunGenes [17], Python 3.10.8 and the RESCRIPt [50] package in QIIME2 2021.11 [5].

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) of the mcrA gene was performed using the primers mlas-mod-F and mcrA-rev-R [2, 62]. Each qPCR reaction was set up in triplicate using a Mosquito HV (SPT Labtech, UK) and performed as described in Tsola et al. [68]. Reactions contained 0.5 µL gDNA (normalised to 3 ng/µL), 0.1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 2.5 µL SensiFAST SYBR (No-ROX,Meridian Bioscience, USA) and 1.8 µL ultra-pure water. A melt curve analysis was performed to detect non-specific DNA products by increasing the temperature from 65 to 95 °C in 0.5 °C increments. Standard curves were produced using a serial 10-fold dilution of clones containing the mcrA gene. The efficiency of all reactions was between 90 and 110%, and the R2 value for the standard curves was > 99%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the sequencing data and the principal coordinate analyses (PCoA) with Bray–Curtis dissimilarity were performed using the R package microeco [35]. Spearman’s correlation analyses (rs) between the first three PCoA coordinates and experimental variables, such as DMS consumption, methane and CO2 production, and grain size, were conducted using PAST (4.2; [20]). Data were visualised using R (4.2.1) on RStudio (2022.07.1; [49]) and ggplot2 [74].

Shotgun metagenomics

Shotgun metagenomics analysis of the sediment sample from the River Pant microcosm was conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI) using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (2 × 150 bp). The DNA sample had a concentration of 10 ng/µL as measured by Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA), an A260/280 ratio of 1.75 and an A260/230 ratio of 1.88. The sequence analysis was carried out following a well-established JGI-created workflow [13].

The MetaCyc and KEGG databases were used to find the genes associated with methylotrophic methanogenesis and other key genes in methanogenesis (Supplementary Table 2; [9, 27]). The gene counts in the metagenome dataset were normalised using the CPM (copies per million) normalisation method [51]. The CPM values were then log-transformed and shown in a heatmap using R (4.2.1) on RStudio (2022.07.1) and ggplot2 [49, 74].

The genes associated with methylotrophic methanogenesis were further explored for their taxonomic affiliation and grouped according to their genera. This was achieved using the JGI analysis output and confirmed by the nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; [8]).

Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) were recovered using MetaBAT 2.12.1 [28]. CheckM 1.0.12 was used for genome completion and contamination estimates [48]. The MAGs were characterised as high (HQ) or medium quality (MQ) according to the Minimum Information about Metagenome-Assembled Genome (MIMAG) standards [6]. The MAGs, which do not contain all rRNA genes were classified as medium-quality. Taxonomic affiliation was inferred using the Integrated Microbial Genome (IMG) and GTDB-tk (0.2.2) databases [11, 12].

Results

DMS-dependent methane production in sediments with different grain sizes

Sediment grain size analysis showed Rivers Pant and Rib had permeable gravel riverbed sediments (gravel fraction: 66.7 and 59.8%, respectively), whereas Rivers Medway and Nadder had less permeable sandy sediments (sand fraction: 86 and 90.1%, respectively).

Methane production was observed in all DMS-amended microcosms although there was a lag phase before methanogenesis started (Fig. 2). Total methane generation was significantly higher in sandy Medway and Nadder sediments at 193 ± 1 and 167 ± 2 µmol methane g−1 than the gravel sediments from Pant and Rib at 22 ± 1 and 15 ± 0.5 µmol g−1 (p < 0.05). Stoichiometrically, 1 mol of DMS can be converted to a maximum of 1.5 mol of methane, therefore, these values correspond to methane yields of 83 and 92% in Medway and Nadder, whilst to 40 and 48% in Pant and Rib, respectively. It should also be noted that Medway and Nadder sediments exhibited considerably longer incubation periods (108 and 134 days, respectively) than Pant and Rib sediments (54 days) until methane production reached the peak concentration (Fig. 2A).

A Average DMS and methane concentrations in river sediment microcosms using DMS as the only energy and carbon source. Rivers Pant and Rib have gravel-dominated riverbeds, whereas Rivers Medway and Nadder have sand-dominated riverbeds. Error bars were omitted to make the graph legible. Black line: DMS concentrations, red line: Methane concentrations. B Total concentrations of DMS degraded, and methane and CO2 produced at the end of the incubation period. Error bars represent standard error above and below the average of five replicates

CO2 production was also measured in the microcosms (Fig. 2B). The highest CO2 production occurred in the River Medway microcosms with 95 ± 3 µmol CO2 g−1 wet sediment. This value was higher than the theoretical CO2 yield if DMS is only used through methanogenesis (77 µmol g−1, [57, 65]), suggesting an alternative pathway, such as sulfate-reduction, to CO2 production in this sediment. On the other hand, CO2 concentrations in River Nadder sediment accounted for 57% of the theoretical CO2 yield (60 µmol CO2 g−1). Rivers Pant and Rib had appreciably lower CO2 productions at 4.28 ± 0.3 µmol CO2 g−1 and 2.04 ± 0.2 µmol CO2 g−1, respectively, corresponding to 12 and 9% of theoretical yields, pointing toward simultaneous CO2 consumption in these sediment microcosms.

Diversity of methanogens in river sediments and DMS-amended microcosms

To identify the methanogens in the sediment microcosms with DMS, the mcrA gene was sequenced. A total of 1.4 × 106, quality-filtered, chimaera-free mcrA sequences were obtained and assigned to 5240 ASVs.

The methanogen diversity varied in the original and control sediments and was dominated by uncultured Methanosarcinales at relative abundances between 41 and 86%. Uncultured Methanomicrobiales (3–36%) and Methanosarcina (2–9%) were also observed, while Rib and Medway sediments additionally had Methanothrix (4–14%; Fig. 3A). The methanogen diversity shifted significantly when the sediments were incubated with DMS (PERMANOVA, p < 0.001), yet no significant difference was observed between the DMS-amended gravel and sandy riverbed sediments (PERMANOVA, p > 0.05). This suggests that the community structure of the DMS-degrading methanogens was not affected by the sampling site and grain size. Methanomethylovorans became the dominant methanogen genus in the microcosms with relative abundances between 53 and 91%, increasing from ~ 2% in River Pant sediments, ~ 0.4% in River Medway and undetectable levels in the sediments from Rivers Rib and Nadder (Fig. 3A). An increase in the relative abundance of Methanosarcina (22 ± 5%) and Methanococcoides (42 ± 15%) was also observed in the River Pant and River Medway microcosms, respectively.

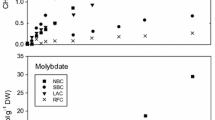

A Average relative abundance of the methanogens at the genus level in five original river sediment samples and five replicated DMS microcosms per site as determined via the amplification of the mcrA gene. B Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plots of the mcrA sequences based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metrics. Ellipses indicate 95% confidence intervals according to treatment data. Colours indicate treatment. Shapes indicate sampling sites. C Mean copy number of the mcrA gene per gram of sediment. Ori: Original sediment samples. Con: Sediment samples from the control microcosms. DMS: Sediment samples from the DMS-amended microcosms. Error bars represent standard error above and below the average of five replicates

The number of methanogens increased in all DMS-amended sediments compared to the original and control sediments (Fig. 3C). River Medway had the highest abundance of in situ methanogens, which also exhibited the highest increase following the DMS addition from 2.3 × 107 ± 0.6 × 107 copies g−1 to 9.1 × 108 ± 1.8 × 108 copies g−1. The other river sediment DMS microcosms had similar methanogen abundances in the original sediments (0.2 × 106–2.9 × 106 copies g−1) and after DMS amendment (1.9 × 108–3.9 × 108 copies g−1) despite the difference in sediment grain sizes (Fig. 3C).

Spearman’s r correlation analysis of the PCoA coordinates showed that 71.3% of the factors affecting the methanogen community structure can be attributed to DMS degradation, and methane and CO2 production (rs = 0.9, p < 0.001; Fig. 3B; Table 1). PCo2 correlated positively with grain size (rs = 0.4, p < 0.05), although no significant change was observed in the methanogen diversity between the sediment samples due to the grain size (Table 1).

Taxonomic analysis of metagenomes and potential metabolic pathways

Taxonomic assignment of the metagenomic sequences from the River Pant DMS microcosms showed that Methanosarcina and Methanomethylovorans dominated the archaeal populations with relative abundances of 50 and 32%, respectively, as was also detected by mcrA sequencing. These genera have been reported to include DMS-degrading strains [38, 39, 41, 45]. The mtsA, mtsB and mtsH genes, which were shown to be the key genes in the DMS-dependent methane production in pure cultures of Methanosarcina barkeri and Methanosarcina acetivorans, had low relative abundances in the metagenomic dataset (0.02, 0.02 and 0.01%, respectively) and belonged to Methanosarcina (Fig. 4B,[18, 63]). The mtsF and mtsD genes were found in comparatively higher relative abundances (0.30 and 0.64%, respectively) and were taxonomically assigned to Methanosarcina and Methanomethylovorans (Fig. 4A and B). This suggests they are likely involved in DMS degradation in the River Pant sediment. Amongst the other methylotrophic methanogenesis-related genes, the methanol-, trimethylamine- and dimethylamine-specific methyltransferases, mtaA, mttB and mtbB, stand out with the highest relative abundances at 2.1, 2, and 2.3%, respectively (Fig. 4A). These genes were most closely affiliated with Methanosarcina, Methanomethylovorans and Methanolobus (Fig. 4B). The rest of the methylotrophic methanogenesis-related genes (mtmBC, mtbABC, mttC, and mtaBC) had 0.8–1.8% relative abundance and were primarily assigned to the genera Methanosarcina, Methanomethylovorans and Methanolobus (Fig. 4B).

A Heatmap showing the abundance of genes involved in methylotrophic methanogenesis in River Pant sediment microcosm with DMS. CPM: Copies per million reads. MMA: Monomethylamine, DMA: Dimethylamine, TMA: Trimethylamine, DMS: Dimethylsulfide, MT: Methanethiol, Me: Methanol B Bubble graph showing the abundance of the methanogens affiliated with methylotrophic methanogenesis-related genes in River Pant sediment microcosm with DMS. Other: Genera with a gene copy number < 50

All the genes in the mcrABCDG operon, which encodes methyl-CoM reductase catalysing the final step in methane formation, had a relative abundance of 0.4% (Supplementary Fig. 1). These mcr genes were from the genera Methanosarcina, Methanomethylovorans and Methanolobus. Furthermore, several other genes in central methanogenic pathways (e.g. mtrA-H, hdrABCD, mvdADG, frhB) were found, however, the fpo and vho genes catalysing coenzyme B/coenzyme M regeneration were not retrieved from the metagenome sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A total of eight metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) were obtained from the Pant metagenome dataset (seven medium quality and one high quality; Supplementary Table 3). Yet, no methanogen MAG was recovered.

Discussion

The importance of rivers and streams for global methane emissions has only recently been recognised. Therefore, knowledge of the microorganisms and pathways underlying the production of methane in river sediments is limited.

All the river sediments tested within this study demonstrated considerable potential to produce methane via DMS degradation. The sandy sediments from River Medway and Nadder had the highest DMS-to-methane yields with 83 and 92%. To the best of our knowledge, this is the maximum recorded methane yield from DMS degradation, which highlights the substantial potential of DMS as a methane precursor in sandy, less permeable river sediments. Interestingly, we previously showed a 41% methane yield in River Medway sediment [68]. Higher rainfall and river flow followed by increased aeration and decreased nutrient concentrations were likely the reasons for lower methanogenic activity in our previous study. River Medway received 18 mm of rainfall in November 2018 compared to the 7 mm rainfall in March 2021 when we carried out sampling for the current study [70, 71]. Despite substantial DMS-dependent methanogenesis potential in all river sediments, there was a large difference in yields between the sediments with different grain sizes. The gravel Pant and Rib sediments exhibited methane yields between 40 and 48%, which are lower than those obtained from the sandy riverbed sediments but comparable to a study by Kiene et al. [29] on lake sediment (63%) and our previous study on River Medway (41%). In addition to the permeability differences, sandy river sediments might have received more nutrients and organic material than gravel sediments, which likely led to higher methane yields [44, 60].

Methanomethylovorans dominated the DMS-amended sediments from all rivers although the only original samples we detected this genus were from the Rivers Pant and Medway. This points towards DMS-degrading methanogens having low in situ abundances in river sediments tested here. Methanomethylovorans are known methylotrophic methanogens, which were shown to degrade DMS in freshwater ecosystems [10, 23, 38, 39, 68]. Our results demonstrated that the grain size and consequently the sediment permeability of river sediments did not affect the diversity of methanogens with DMS degradation potential, however, it strongly affected the capacity of this genus to degrade the available DMS to methane since different methane yields were obtained from different samples. Methanosarcina also increased in Rivers Pant and Rib following the addition of DMS. Members of the genus Methanosarcina are known to utilise most methanogenic substrates, including DMS [14, 41, 45, 61]. Therefore, Methanosarcina species likely performed DMS-dependent methanogenesis in the River Pant and Rib sediments. Similarly, Methanococcoides, another methylotrophic methanogen genus, increased in Rivers Pant, Rib and Medway, following the addition of DMS although no member of the Methanococcoides genus has been shown to degrade DMS before [21, 33, 34]. Alternatively, they might have performed mixotrophy using CO2 produced as a metabolite during DMS degradation as was previously shown for Methanococcoides methylutens [78]. Methanococcoides are typically associated with saline environments such as saltmarshes, brackish lakes and tidal flats [43, 69, 75]. A plausible way for Methanococcoides to be introduced to River Pant, Rib and Medway sediments is via runoff from the surrounding terrestrial soils, where these methanogens have previously been found [72]. In River Medway, Methanococcoides have likely been transported from the marine sediments via tidal mixing since this river is part of the macrotidal Medway Estuary [68].

We analysed the key functional genes of methylotrophic methanogenesis in the metagenomics datasets and found that the mtsA, mtsB, mtsF and mtsH genes had the lowest abundance despite the Mts enzyme having been recognised as the key DMS methyltransferase [18, 63, 64]. mtsD was the only mts gene found in relatively high abundance (0.64% compared to < 0.02%) and was likely involved in DMS-dependent methanogenesis in the river sediments tested. On the other hand, the mtaA, mttB and mtbB were found at high relative abundances (2.1–2.3%), suggesting that DMS-degrading methanogens in our samples used methanol-, trimethylamine- or dimethylamine-methyltransferase to transfer the methyl group from DMS to Co-M. This is similar to our recent study, where, using metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, we showed that Methanolobus likely used trimethylamine and methanol methyltransferases to degrade DMS in Baltic Sea sediments [67]. Alternatively, there may be currently unknown genes or pathways of DMS-dependent methanogenesis.

Conclusion

This was the first study investigating methane production via DMS degradation in river sediments with contrasting riverbed geologies. Our results highlight the previously overlooked potential of DMS as a methane precursor in river ecosystems particularly those with sandy sediments. Methanomethylovorans were the dominant DMS-degrading methanogens in all sampling sites regardless of the gravel size, highlighting a significant role for this genus in riverine methane production. Hence, the contribution of DMS to methane production in river sediments and the response of Methanomethylovorans to changing climatic conditions warrant further study to better understand the methane production pathways in rivers and predict the future global methane budget.

Availability of data and materials

All sequence data produced in this study are publicly available. The mcrA gene sequences are deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with the BioProject ID PRJNA1083105. The metagenomics dataset is available in the JGI GOLD database (Project ID: Gp0507774). All scripts for figure creation and sequence analysis are available on Github and Zenodo (Tsola 2024, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10775199).

References

Allen GH, Pavelsky T. Global extent of rivers and streams. Science. 2018;361:585–8.

Angel R, Claus P, Conrad R. Methanogenic archaea are globally ubiquitous in aerated soils and become active under wet anoxic conditions. ISME J. 2012;6:847–62.

Bodmer P, Wilkinson J, Lorke A. Sediment properties drive spatial variability of potential methane production and oxidation in small streams. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JG005213.

Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Rideout JR, Dillon M, Bolyen E, Knight R, et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018;6:1–17.

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–7.

Bowers RM, Kyrpides NC, Stepanauskas R, Harmon-Smith M, Doud D, Reddy TBK, et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:725–31.

Brimblecombe P, Shooter D. Photo-oxidation of dimethylsulphide in aqueous solution. Mar Chem. 1986;19:343–53.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:1–9.

Caspi R, Altman T, Billington R, Dreher K, Foerster H, Fulcher CA, et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:459–71.

Cha I-T, Min U-G, Kim S-J, Yim KJ, Roh SW, Rhee S-K. Methanomethylovorans uponensis sp. nov., a methylotrophic methanogen isolated from wetland sediment. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2013;104:1005–12.

Chaumeil PA, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:1925–7.

Chen IMA, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Ratner A, Huang J, Huntemann M, et al. The IMG/M data management and analysis system vol 6.0: new tools and advanced capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D751–63.

Clum A, Huntemann M, Bushnell B, Foster B, Foster B, Roux S, et al. DOE JGI metagenome workflow. mSystems. 2021;6:e00804-e820.

Elberson MA, Sowers KR. Isolation of an aceticlastic strain of Methanosarcina siciliae from marine canyon sediments and emendation of the species description for Methanosarcina siciliae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1258–61.

Eyice Ö, Namura M, Chen Y, Mead A, Samavedam S, Schäfer H. SIP metagenomics identifies uncultivated Methylophilaceae as dimethylsulphide degrading bacteria in soil and lake sediment. ISME J. 2015;9:2336–48.

Finster K, Tanimoto Y, Bak F. Fermentation of methanethiol and dimethylsulfide by a newly isolated methanogenic bacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:425–30.

Fish JA, Chai B, Wang Q, Sun Y, Brown CT, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. FunGene: the functional gene pipeline and repository. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:1–14.

Fu H, Metcalf WW. Genetic basis for metabolism of methylated sulfur compounds in Methanosarcina species. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:1515–24.

Glud RN. Oxygen dynamics of marine sediments. Mar Biol Res. 2008;4:243–89.

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaentol Electron. 2001;4:1–9.

Jameson E, Stephenson J, Jones H, Millard A, Kaster AK, Purdy KJ, et al. Deltaproteobacteria (Pelobacter) and Methanococcoides are responsible for choline-dependent methanogenesis in a coastal saltmarsh sediment. ISME J. 2019;13:277–89.

Janssen F, Huettel M, Witte U. Pore-water advection and solute fluxes in permeable marine sediments (II): benthic respiration at three sandy sites with different permeabilities (German Bight, North Sea). Limnol Oceanogr. 2005;50:779–92.

Jiang B, Parshina SN, van Doesburg W, Lomans BP, Stams AJM. Methanomethylovorans thermophila sp. nov., a thermophilic, methylotrophic methanogen from an anaerobic reactor fed with methanol. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:2465–70.

Jones JB, Mulholland PJ. Influence of drainage basin topography and elevation on carbon dioxide and methane supersaturation of stream water. Biogeochemistry. 1998;40:57–72.

Kadam PC, Ranade DR, Mandelco L, Boone DR. Isolation and characterization of Methanolobus bornbayensis sp. nov., a methylotrophic methanogen that requires high concentrations of divalent cations. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:603–7.

Kamann PJ, Ritzi RW, Dominic DF, Conrad CM. Porosity and permeability in sediment mixtures. Ground Water. 2007;45:429–38.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Ishiguro-Watanabe M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963.

Kang DD, Froula J, Egan R, Wang Z. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ. 2015;2015:1–15.

Kiene RP, Oremland RS, Catena A, Miller LG, Capone DG. Metabolism of reduced methylated sulfur compounds in anaerobic sediments and by a pure culture of an estuarine methanogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1037–45.

King T, Butcher S, Zalewski L. Apocrita—high performance computing cluster for Queen Mary University of London, pp. 3–4, 2017.

Lansdown K, McKew BA, Whitby C, Heppell CM, Dumbrell AJ, Binley A, et al. Importance and controls of anaerobic ammonium oxidation influenced by riverbed geology. Nat Geosci. 2016;9:357–60.

Lever MA, Teske AP. Diversity of methane-cycling archaea in hydrothermal sediment investigated by general and group-specific PCR primers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:1426–41.

L’Haridon S, Chalopin M, Colombo D, Toffin L. Methanococcoides vulcani sp. nov., a marine methylotrophic methanogen that uses betaine, choline and N, N-dimethylethanolamine for methanogenesis, isolated from a mud volcano, and emended description of the genus Methanococcoides. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:1978–83.

Liang L, Sun Y, Dong Y, Ahmad T, Chen Y, Wang J, Wang F. Methanococcoides orientis sp. nov., a methylotrophic methanogen isolated from sediment of the East China Sea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2022;72:005384.

Liu C, Cui Y, Li X, Yao M. Microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2021;97:1–9.

Liu Y, Boone DR, Choy C. Methanohalophilus oregonense sp. nov. a methylotrophic methanogen from an alkaline, saline aquifer. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:111–6.

Lohse L, Malschaert JFP, Slomp CP, Helder W, van Raaphorst W. Sediment-water fluxes of inorganic nitrogen compounds along the transport route of organic matter in the North Sea. Ophelia. 1995;41:173–97.

Lomans BP, Op den Camp HJM, Pol A, van der Drift C, Vogels GD. Role of methanogens and other bacteria in degradation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2116–21.

Lomans BP, Op Den Camp HJM, Pol A, Vogels GD. Anaerobic versus aerobic degradation of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol in anoxic freshwater sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:438–43.

Lovley DR, Klug MJ. Methanogenesis from methanol and methylamines and acetogenesis from hydrogen and carbon dioxide in the sediments of a eutrophic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:1310–5.

Lyimo TJ, Pol A, Op Den Camp HJM, Harhangi HR, Vogels GD. Methanosarcina semesiae sp. nov., a dimethylsulfide-utilizing methanogen from mangrove sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:171–8.

Mathrani IM, Boone DR, Mah RA, Fox GE, Lau PP. Methanohalophilus zhilinae sp. nov., an alkaliphilic, halophilic, methylotrophic methanogen. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:139–42.

Munson MA, Nedwell DB, Embley TM. Phylogenetic diversity of Archaea in sediment samples from a coastal salt marsh. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4729–33.

Murphy RR, Kemp WM, Ball WP. Long-term trends in Chesapeake Bay seasonal hypoxia, stratification, and nutrient loading. Estuaries Coasts. 2011;34:1293–309.

Ni S, Boone DR. Isolation and characterization of a dimethlyl sulphide-degrading methanogen, Methanolobus siciliae HI350, from an oil well, characterization of M. siciliae T4/MT, and emendation of M. siciliae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1991;41:410–6.

Oelgeschläger E, Rother M. In vivo role of three fused corrinoid/methyl transfer proteins in Methanosarcina acetivorans. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:1260–72.

Oremland RS, Boone DR. Methanolobus taylorii sp. nov., a new methylotrophic, estuarine methanogen. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:573–5.

Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–55.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2020.

Robeson MS, O’Rourke DR, Kaehler BD, Ziemski M, Dillon MR, Foster JT, Bokulich NA. RESCRIPt: reproducible sequence taxonomy reference database management. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(11):e1009581.

Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:1–9.

Rocher-Ros G, Stanley EH, Loken LC, Casson NJ, Raymond PA, Liu S, et al. Global methane emissions from rivers and streams. Nature. 2023;621:530–5.

Rosentreter JA, Al-Haj AN, Fulweiler RW, Williamson P. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions complicate coastal blue carbon assessments. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2021;35:1–8.

Sanders IA, Heppell CM, Cotton JA, Wharton G, Hildrew AG, Flowers EJ, Trimmer M. Emission of methane from chalk streams has potential implications for agricultural practices. Freshw Biol. 2007;52:1176–86.

Schäfer H, Eyice Ö. Microbial cycling of methanethiol. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2019;33:173–81.

Schäfer H, Myronova N, Boden R. Microbial degradation of dimethylsulphide and related C1-sulphur compounds: organisms and pathways controlling fluxes of sulphur in the biosphere. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:315–34.

Scholten JCM, Murrell JC, Kelly DP. Growth of sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic archaea with methylated sulfur compounds: a commentary on the thermodynamic aspects. Arch Microbiol. 2003;179:135–44.

Shelley F, Ings N, Hildrew AG, Trimmer M, Grey J. Bringing methanotrophy in rivers out of the shadows. Limnol Oceanogr. 2017;62:2345–59.

Shen LD, Ouyang L, Zhu Y, Trimmer M. Active pathways of anaerobic methane oxidation across contrasting riverbeds. ISME J. 2019;13:752–66.

Sigleo AC, Frick WE. Seasonal variations in river discharge and nutrient export to a Northeastern Pacific estuary. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2007;73:368–78.

Sowers KR, Baron SF, Ferry JG. Methanosarcina acetivorans sp. nov., an acetotrophic methane- producing bacterium isolated from marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:971–8.

Steinberg LM, Regan JM. mcrA-targeted real-time quantitative PCR method to examine methanogen communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4435–42.

Tallant TC, Krzycki JA. Methylthiol:coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcina barkeri, an enzyme of methanogenesis from dimethylsulfide and methylmercaptopropionate. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6902–11.

Tallant TC, Paul L, Krzycki JA. The MtsA subunit of the methylthiol:coenzyme M methyltransferase of Methanosarcina barkeri catalyses both half-reactions of corrinoid-dependent dimethylsulfide: coenzyme M methyl transfer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4485–93.

Tanimoto Y, Bak F. Anaerobic degradation of methylmercaptan and dimethyl sulfide by newly isolated thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2450–5.

Trimmer M, Hildrew AG, Jackson MC, Pretty JL, Grey J. Evidence for the role of methane-derived carbon in a free-flowing, lowland river food web. Limnol Oceanogr. 2009;54:1541–7.

Tsola SL, Zhu Y, Chen Y, Sanders IA, Economou CK, Brüchert V, Eyice Ö. Methanolobus use unspecific methyltransferases to produce methane from dimethylsulphide in Baltic Sea sediments. Microbiome. 2024;12:1–13.

Tsola SL, Zhu Y, Ghurnee O, Economou CK, Trimmer M, Eyice Ö. Diversity of dimethylsulfide-degrading methanogens and sulfate-reducing bacteria in anoxic sediments along the Medway Estuary, UK. Environ Microbiol. 2021;23:4434–49.

Watanabe T, Cahyani VR, Murase J, Ishibashi E, Kimura M, Asakawa S. Methanogenic archaeal communities developed in paddy fields in the Kojima Bay polder, estimated by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, real-time PCR and sequencing analyses. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2009;55:73–9.

Weekly rainfall and river flow summary—03 March–09 March 2021. Environmental Agency 2021, version archived 16 March 2021. Retrieved from the UK Government Web Archive: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20210316210138/https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/weekly-rainfall-and-river-flow-reports-for-england. Accessed 16 Dec 2022.

Weekly rainfall and river flow summary—31 October–06 November 2018. Environmental Agency 2018, version archived 10 November 2018. Retrieved from the UK Government Web Archive: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20181110235457/https://www.gov.u204k/government/publications/weekly-rainfall-and-river-flow-reports-for-england. Accessed 16 Dec 2022.

Wen X, Yang S, Horn F, Winkel M, Wagner D, Liebner S. Global biogeographic analysis of methanogenic archaea identifies community-shaping environmental factors of natural environments. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–13.

Wentworth CK. A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J Geol. 1922;30:377–92.

Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Cham: Springer; 2016.

Wilms R, Sass H, Köpke B, Köster J, Cypionka H, Engelen B. Specific bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic communities in tidal-flat sediments along a vertical profile of several meters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2756–64.

Wilson WH, Carr NG, Mann NH. The effect of phosphate status on the kinetics of cyanophage infection in the oceanic cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. WH7803. J Phycol. 1996;32:506–16.

Wyman M, Gregory RP, Carr NG. Novel role for phycoerythrin in a marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus strain DC2. Science. 1985;230:818–20.

Yin X, Wu W, Maeke M, Richter-Heitmann T, Kulkarni AC, Oni OE, et al. CO2 conversion to methane and biomass in obligate methylotrophic methanogens in marine sediments. ISME J. 2019;13:2107–19.

Funding

Stephania L. Tsola was funded by the Queen Mary University of London PhD studentships. The work (proposal: https://doi.org/10.46936/10.25585/60001216) conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (http://ror.org/04xm1d337), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, is supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ö.E. conceived the idea of the study. Ö.E. and S.L.T. designed the experiments. I.A.S. and S.L.T collected samples. S.L.T., A.A.P., L.F.S. and C.K.E. carried out the experiments and performed the analysis. Ö.E. and S.L.T. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Ö.E. is a Senior Editor of Environmental Microbiome. However, they were not involved in the Handling Editor or Reviewer selection processes or at any other stage of the evaluation and decision process.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsola, S.L., Prevodnik, A.A., Sinclair, L.F. et al. Methanomethylovorans are the dominant dimethylsulfide-degrading methanogens in gravel and sandy river sediment microcosms. Environmental Microbiome 19, 51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-024-00591-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-024-00591-4