Abstract

Background

The finding of a vermiform appendix within the peritoneal sac of an inguinal hernia is called Amyand’s hernia. The reported incidence of Amyand’s hernia and femoral hernia is 1% and 3.8%, respectively. To our knowledge, no cases have been reported in the literature that associate these two entities. We present the first case of incarcerated left-sided Amyand’s hernia and synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia found during emergency surgery.

Case presentation

A 72-year-old woman was admitted to the Emergency Department for a complicated left inguinal hernia. An inguinotomy was performed that detected a large direct hernial sac and a synchronous femoral hernia. The opening of the inguinal hernia showed the presence of the cecum and the appendix, both without signs of inflammation. The femoral space was evaluated transinguinally, identifying the larger omentum that had slipped into the femoral canal. The primary closure of the posterior wall defect was performed with the McVay technique due to its large size, and then the hernioplasty was completed with a polypropylene mesh. No postoperative complications were reported.

Conclusions

In the context of an incarcerated Amyand’s hernia, the decision to perform an appendectomy in addition to hernia repair with or without mesh will depend on intraoperative findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The protrusion of the vermiform appendix into an inguinal hernia is called “Amyand’s hernia”. The true incidence of Amyand’s hernia is difficult to establish. Large retrospective studies report rates between 0.14 and 1.3% in inguinal hernia series [1]. Most of them occur on the right side, due to the anatomical position of the appendix. However, the presence of Amyand’s hernia on the left side represents an extremely rare entity, with an incidence of up to 9.5% [1, 2]. On the other hand, an incidence of femoral hernias has been reported in patients who received a preoperative diagnosis of inguinal hernia of up to 13% [3]. We present the first case of incarcerated left-sided Amyand’s hernia and synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia found during emergency surgery.

Case presentation

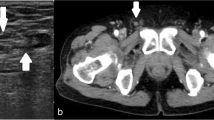

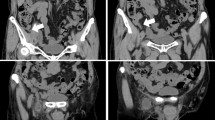

A 72-year-old woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and arterial hypertension was admitted to the Emergency Department due to abdominal pain and nausea of 24 h evolution. She denied any other symptoms. Upon admission, the patient had a pulse of 112 bpm, blood pressure of 105/85 mmHg, and a temperature of 36.3 °C. On physical examination, her abdomen was distended and tender. An irreducible mass with intense pain on palpation was detected in the left inguinal region. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis of 11.4 × 109 /L and lactate of 0.7 mmol/L. The metabolic profile and liver function tests were within normal limits. Inguinal ultrasound reported the protrusion of a hollow viscus through a 42 mm fascial continuum. Taking into account the patient's history and the findings of an incarcerated inguinal hernia, emergency surgical treatment was chosen. An anterior approach was performed through an inguinal incision. On examination, a large direct hernial sac protruding from a 6 × 5 cm posterior wall defect and a synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia were observed. The inguinal hernial sac was opened, showing the presence of the cecum and the appendix (Fig. 1), both without signs of inflammation or ischemia (Losanoff–Basson type 1), so the sac was resected and its contents reintroduced into the abdominal cavity. The femoral space was then evaluated transinguinally, identifying the greater omentum that had slipped into the femoral canal (Fig. 2). Subsequently, a transinguinal dissection of the femoral hernia was performed and its content was reduced. For the reconstructive phase, we consider the existence of a large defect remaining in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal after resection of the hernia sac, associated with the need to repair the found femoral hernia. Given these intraoperative findings, primary closure of the large posterior wall defect and the femoral ring was performed by primary McVay repair. Finally, the hernia repair was completed with the placement of a 15 × 7 cm polypropylene mesh. The procedure was carried out without complications and was discharged on the first postoperative day. No recurrence was detected 12 months after surgery.

Anterior view of the left inguinal region after dissection and opening of the direct inguinal hernial sac. Gauze was inserted to partially reduce its contents to the abdominal cavity during dissection. A cecum, B appendix, C inguinal ligament, D femoral hernia. The dashed dot indicate the boundaries of the inguinal and femoral hernia defects

Discussion

To our knowledge, no case has been reported in the literature that associates the presentation of left-sided Amyand’s hernia and synchronous femoral hernia found during emergency hernioplasty. It has been shown in large cohort studies and case series that these two entities have a very low incidence in isolation, so their association could be considered extremely rare.

The pathophysiology of Amyand's hernia is still unclear and its true incidence is difficult to establish. Left-sided Amyand’s hernia has been reported to be usually the result of mobile cecum syndrome and the presence of an excessively long appendix. However, theoretically it can occur in situs inversus or malrotation [2]. Furthermore, in cases of complete appendiceal protrusion into the sac, a portion of the cecum also protrudes [4]. This agrees with our findings and we believe that in our case the pathophysiology of Amyand’s hernia involved the presence of a mobile cecum protruding through the posterior wall of the left inguinal canal.

The clinical picture of Amyand’s hernia is that of an inguinal hernia and is mainly dependent on the inflammatory state of the appendix [5]. It has been reported that up to 83% of cases present with a painful inguinal or inguinoscrotal mass [6], as in the case presented here.

The differential diagnosis is broad and should include an irreducible, incarcerated or strangulated hernia, acute appendicitis, urologic emergencies (testicular torsion, orchiepididymitis, acute hydrocele) and skin complications (inguinal abscess, lymphadenopathy) [1].

Imaging studies are essential for the preoperative diagnosis of Amyand’s hernia, as well as for occult hernias of the inguinal region. Computed tomography (CT) and abdominopelvic ultrasound can demonstrate a tubular structure arising from the cecum and extending into the inguinal sac [7]. However, they are not routine studies when a complicated inguinal hernia is clinically suspected, so in most cases Amyand’s hernia is diagnosed intraoperatively [6]. In the cases of painful, irreducible hernias or suspected incarceration, immediate surgical intervention is clearly indicated, and many surgeons do not perform imaging studies for confirmation [4]. In our report, we did not perform a CT due to the clinical presentation and ultrasound finding of intestinal content stuck in an inguinal hernia, prioritizing emergency surgical treatment.

Regarding the surgical approach, Losanoff and Basson proposed a classification to identify and determine the treatment of Amyand’s hernia, depending on the presence of acute appendicitis and abdominal sepsis [8]. Our case corresponds to a type 1 hernia, defined as an Amyand’s hernia that contains a normal appendix within the hernial sac, for which reduction and repair with mesh is recommended. Although some authors favor routine appendectomy, others do not support it in the absence of inflammation.

Furthermore, even elective appendectomy transforms a clean procedure into a clean contaminated one, slightly increasing the risk of septic complications and mesh infection [9]. We decided not to resect the appendix due to its indemnity, which was reintroduced into the abdominal cavity together with the cecum contained in the hernia sac. Types 2, 3, and 4 involve an inflamed appendix, a perforated appendix, and complicated intra-abdominal pathology, respectively. In these cases, appendectomy and mesh-free hernia repair are recommended.

Recommendations for the treatment of inguinal hernias include mesh and tension-free repair [5]. Furthermore, in the case of direct hernias, the primary closure of the direct defect should be considered once the hernia contents have been reduced [10]. In our case, we decided to perform primary closure of the direct defect with a repair of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal with the McVay technique, due to the large extension of the remaining defect and the concomitant need to repair the femoral ring. As there was no evidence of a contaminated field, we completed the hernia repair by placing of a polypropylene mesh, placed above the primary repair. An alternative for reconstruction would have been an open preperitoneal anterior approach, but this was ruled out due to the large extent of the remaining posterior wall defect after the section of the hernia sac.

Compared to inguinal hernias, femoral hernias are rare and according to different series and cohort studies, they represent 2–13% of inguinal hernia repairs [3, 11]. Unlike inguinal hernias, femoral hernias are more likely to require urgent repair and are associated with a higher rate of complications and morbidity [12].

Given the low incidence of these two entities, systematic reviews of case reports and case series will likely remain the best available level of evidence for the foreseeable future.

Conclusions

This is the first reported case of an incarcerated left-sided Amyand’s hernia with a synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia found during an emergency hernioplasty. The decision to perform an appendectomy and hernia repair with or without mesh placement will depend on the intraoperative findings. In addition, open primary tissue approximation nonmesh repairs, such as the McVay technique, are valid alternatives to herniorrhaphy, especially if infection is found.

Availability of data and materials

The data are not available for public access because of patient privacy concerns, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

27 February 2023

The family name of René M. Palacios Huatuco has been updated.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Manatakis DK, Tasis N, Antonopoulou MI, Anagnostopoulos P, Acheimastos V, Papageorgiou D, et al. Revisiting Amyand’s hernia: a 20-year systematic review. World J Surg. 2021;45:1763–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-05983-y.

Nowrouzi R. Left-sided Amyand hernia: case report and review of the literature. Fed Pract. 2021;38:286–90. https://doi.org/10.12788/fp.0136.

Waltz P, Luciano J, Peitzman A, Zuckerbraun BS. Femoral hernias in patients undergoing total extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair: including routine evaluation of the femoral canal in approaches to inguinal hernia repair. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:292–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3402.

Patoulias D, Kalogirou M, Patoulias I. Amyand’s Hernia: an up-to-date review of the literature. Acta medica (Hradec Kral). 2017;60:131–4. https://doi.org/10.14712/18059694.2018.7.

Michalinos A, Moris D, Vernadakis S. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Am J Surg. 2014;207:989–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.043.

Sharma H, Gupta A, Shekhawat NS, Memon B, Memon MA. Amyand’s hernia: a report of 18 consecutive patients over a 15-year period. Hernia. 2007;11:31–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-006-0153-8.

Tsang WK, Lee KL, Tam KF, Lee SF. Acute appendicitis complicating Amyand’s hernia: imaging features and literature review. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:255–7. https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj133971.

Losanoff JE, Basson MD. Amyand hernia: a classification to improve management. Hernia. 2008;12:325–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-008-0331-y.

Bhangu A, Ademuyiwa AO, Aguilera ML, Alexander P, Al-Saqqa SW, Borda-Luque G, et al. Surgical site infection after gastrointestinal surgery in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: a prospective, international, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:516–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30101-4.

Simons MP, Smietanski M, Bonjer HJ, Bittner R, Miserez M, Aufenacker TJ, et al. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018;22:1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x.

Henriksen NA, Thorup J, Jorgensen LN. Unsuspected femoral hernia in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of recurrent inguinal hernia. Hernia. 2012;16:381–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-012-0924-3.

Murphy BL, Ubl DS, Zhang J, Habermann EB, Farley D, Paley K. Proportion of femoral hernia repairs performed for recurrence in the United States. Hernia. 2018;22:593–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1743-y.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FAC, JFV, and RPH drafted the manuscript. FAC, JFV, and RPH supervised the writing of the manuscript. FAC, JFV, and SB performed perioperative management and operation of the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The local Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required for case reports.

Consent for publication

Patient signed informed consent regarding publishing her data and photographs.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Corvatta, F.A., Palacios Huatuco, R.M., Bertone, S. et al. Incarcerated left-sided Amyand’s hernia and synchronous ipsilateral femoral hernia: first case report. surg case rep 9, 15 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-023-01597-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-023-01597-9