Abstract

Background

Emphysematous pancreatitis is acute pancreatitis associated with emphysema based on imaging studies and has been considered a subtype of necrotizing pancreatitis. Although some recent studies have reported the successful use of conservative treatment, it is still considered a serious condition. Computed tomography (CT) scan is useful in identifying emphysema associated with acute pancreatitis; however, whether the presence of emphysema correlates with the severity of pancreatitis remains controversial. In this study, we managed two cases of severe acute pancreatitis complicated with retroperitoneal emphysema successfully by treatment with lavage and drainage.

Case presentation

Case 1: A 76-year-old man was referred to our hospital after being diagnosed with acute pancreatitis. At post-admission, his abdominal symptoms worsened, and a repeat CT scan revealed increased retroperitoneal gas. Due to the high risk for gastrointestinal tract perforation, emergent laparotomy was performed. Fat necrosis was observed on the anterior surface of the pancreas, and a diagnosis of acute necrotizing pancreatitis with retroperitoneal emphysema was made. Thus, retroperitoneal drainage was performed. Case 2: A 50-year-old woman developed anaphylactic shock during the induction of general anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery, and peritoneal irritation symptoms and hypotension occurred on the same day. Contrast-enhanced CT scan showed necrotic changes in the pancreatic body and emphysema surrounding the pancreas. Therefore, she was diagnosed with acute necrotizing pancreatitis with retroperitoneal emphysema, and retroperitoneal cavity lavage and drainage were performed. In the second case, the intraperitoneal abscess occurred postoperatively, requiring time for drainage treatment. Both patients showed no significant postoperative course problems and were discharged on postoperative days 18 and 108, respectively.

Conclusion

Acute pancreatitis with emphysema from the acute phase highly indicates severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgical drainage should be chosen without hesitation in necrotizing pancreatitis with emphysema from early onset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Emphysematous pancreatitis is a severe form of acute pancreatitis associated with emphysema in imaging studies and has been considered a subtype of necrotizing pancreatitis [1]. In this report, we describe two patients with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis complicated with retroperitoneal emphysema relieved by emergency surgery.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 76-year-old man visited his previous doctor due to vomiting after consuming lunch. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed signs of pancreatitis. He was referred to our hospital the next day. His medical history included untreated diabetes mellitus and gastric ulcer, and he also had a history of alcohol consumption of approximately 60 g per day. On arrival, his pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature were 120 beats/min, 109/68 mmHg, and 37.5℃, respectively. Abdominal findings included mild tenderness in the upper abdomen without peritoneal irritation signs. Laboratory findings on admission were white blood cell (WBC) of 2060 /µL; hemoglobin (Hb), 16.2 g/dL; platelet count (Plt), 16.9 /µL; aspartate transaminase, 48 U/L; alanine transaminase (ALT), 18 U/L; creatinine (Cre), 0.8 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 21 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 254 U/L; amylase (AMY), 1023 U/L; glucose level, 253 mg/dL; glycated hemoglobin 7.3%; and C-reactive protein (CRP), 4.48 mg/dL. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan showed extensive emphysema in the retroperitoneum, increased adipose tissue density around the pancreatic body, and ascites around the pancreatic body (Fig. 1A).

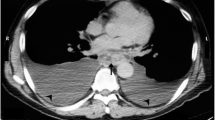

Contrast-enhanced CT scan of case 1. A Initial CT showing the emphysema around the pancreatic body (arrow). B CT performed 6 h post-admission showing a significant increase in retroperitoneal gas (arrow). C, D CT performed 6 h post-admission showing the appearance of gas in the transverse mesocolon (arrows)

Based on the above data, conservative treatment was initiated based on acute pancreatitis and peripancreatic abscess diagnoses. However, immediately after initiating the treatment, peritoneal irritation symptoms occurred. A CT scan was performed again 6 h post-admission and showed no evidence of free gas in the abdominal cavity; however, a significant increase in retroperitoneal gas (Fig. 1B) and the appearance of gas in the transverse mesocolon was observed (Fig. 1C, D). Therefore, with the suspicion of gastrointestinal tract perforation, an emergency laparotomy was performed. During laparotomy, a moderate amount of clear yellow ascites fluid was detected, and edematous changes and inflammatory wall thickening were observed in the transverse colon. Necrotic changes of the pancreatic parenchyma were observed in the anterior pancreatic body, with retroperitoneal emphysema in the dorsal pancreatic body (Fig. 2). When the retroperitoneum was opened, air and purulent effusion were observed. Considering the possibility of necrotizing pancreatitis and transverse colon perforation, partial transverse colon resection, colostomy, lavage, and abdominal drainage were performed. Abscess formation was observed within the removed transverse colon mesentery; however, no grossly visible perforation was observed in the transverse colon. Klebsiella pneumoniae was detected in the purulent fluid collected at the time of surgery, which was consistent with blood culture results at the time of the initial examination. The patient had a good postoperative course, and thus, his pancreatitis was quickly resolved. The patient had no postoperative infectious complications and was discharged on the 18th postoperative day. Eight months after discharge from the hospital, a colostomy closure was performed after confirming his good postoperative recovery.

Case 2

A 50-year-old woman developed anaphylactic shock during the induction of general anesthesia for a planned surgery for a lumbar disk herniation at a previous hospital, and surgery was canceled. On the same day, severe abdominal pain occurred, and she was transferred to our hospital the next day because of the suspected acute pancreatitis on a contrast-enhanced CT scan. Upon arrival, her pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature were 120 beats/min, 90–100 mmHg with noradrenaline of 0.25γ, and 39.1 °C, respectively. She was drowsy, however, and complained of abdominal pain. The abdomen was generally distended with involuntary defense. Livedo reticularis was also observed on the extremities. Her only previous medical history was a lumbar disk herniation, and her social history was unremarkable. On admission, laboratory findings were WBC of 1320 /μL; Hb, 17.3 g/dL; Plt, 253,000 /μL; AST, 97 U/L; ALT, 42 U/L; Cre, 1.59 mg/dL; BUN, 18 mg/dL; LDH, 389 U/L; AMY, 1629 U/L; and CRP, 19.36 mg/dL. An abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan showed a partial area of necrosis in the pancreatic body with extensive emphysema in the surrounding retroperitoneal cavity. Although no intra-abdominal free gas was observed, a large amount of ascites was observed (Fig. 3). Based on these data, the patient was diagnosed with necrotizing pancreatitis with emphysema and septic shock, and an emergency laparotomy was performed.

Intraoperatively, a large amount of turbid ascites fluid was observed. When the omental foramen was opened, necrotic changes were observed in the pancreatic body and surrounding fatty tissues (Fig. 4). No gastrointestinal perforation was observed. The retroperitoneum around the pancreatic body was extensively opened, and fatty tissues with necrotic changes were removed as much as possible. Although necrotic changes were observed in the pancreatic body, the pancreatic parenchyma was preserved, and resection was not necessary. Therefore, lavage and drainage were performed, and drains were placed in the abdominal and retroperitoneal cavities. The purulent ascites fluid collected at the time of surgery was found to contain Escherichia coli, which was consistent with blood culture results during the initial examination.

The patient had a good postoperative course, and vasopressors were discontinued on the 2nd postoperative day. The patient was transferred to the ward from the intensive care unit on the 8th postoperative day. However, the patient developed an organ-space surgical site infection around the pancreatic body. The site infection was refractory, requiring several image-guided drain replacements. Following adequate drainage treatment, the drainage tube was removed on the 101st postoperative day. Consequently, the patient was discharged on the 108th postoperative day.

Discussion

We report two patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis with retroperitoneal emphysema, which developed rapidly and was associated with intra-abdominal infection requiring emergency laparotomy drainage. Both patients were successfully treated with abdominal drainage and improved from a severe condition, and the pancreatitis was treated conservatively.

Emphysematous pancreatitis is a subtype of necrotizing pancreatitis and is considered as acute pancreatitis with emphysema in and around the pancreas [1]. It has been suggested to be associated with alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus, history of abdominal surgery, history of pancreatitis, and gallstones [2]. A history of alcohol consumption of approximately 60 g/day and untreated diabetes mellitus may have been associated with the onset of the disease in case 1. In case 2, the patient developed severe anaphylactic shock during induction of anesthesia for lumbar hernia surgery, rapidly followed by necrotizing pancreatitis, suggesting that drug-induced pancreatitis during induction of anesthesia or pancreatic ischemia due to a sudden drop in blood pressure in the anaphylactic reaction may have been associated with the occurrence of necrotizing pancreatitis. In general, muscle relaxants and antimicrobial agents are the most frequently suspected drugs that result in allergic reactions during induction of anesthesia [3]. Furthermore, several causes of pancreatic tissue ischemia such as vasculitis, atheroembolism, intraoperative hypotension, and hemorrhagic shock were reported [4,5,6,7,8]. In one report, 81 of 300 patients (27%) who underwent cardiac surgery developed hyperamylasemia, and three patients subsequently developed necrotizing pancreatitis [7]. Thus, pancreatic tissue ischemia due to anaphylactic shock may have triggered the occurrence of necrotizing pancreatitis. On the other hand, propofol is also reported as a cause of pancreatitis [9]. Therefore, these drugs in the induction of anesthesia may have contributed to the onset of pancreatitis in our case 2. Reports of emphysematous pancreatitis by Bul et al. revealed that the majority of isolated bacteria were Gram-negative enterobacteria [2]. Conversely, about half of the patients were Gram-positive organisms on culture, most of which were Clostridium perfringens [2]. These bacteria ferment glucose in the necrotic tissues, producing carbon dioxide and nitrogen gas [10]. Patients with poorly controlled diabetes more likely develop infections with emphysema due to increased tissue glucose concentration in the interstitial fluid caused by impaired glycolytic function [10]. However, the pathways by which these bacteria spread to the pancreas and surrounding tissues at the onset of the necrotizing pancreatitis are unclear; hematogenous and lymphatic migration from the gastrointestinal lumen to the peripancreatic area, backflow from the Vater’s papilla into the bile or pancreatic duct, or through a gastrointestinal tract fistula [2]. In our both cases, Gram-negative rods were detected in the peripancreatic abscess and venous blood, Klebsiella pneumoniae in one case, and Escherichia coli in the other case. No fistula was observed between the peripancreatic abscess and gastrointestinal tract, and the environment was not associated with biliary infection, suggesting the involvement of bacterial translocation. Any shock that disrupts the normal intestinal barrier can compromise the barrier function, resulting in bacterial translocation and infection in humans [11]. Bacterial translocation in humans is assumed to occur in several clinical manifestations—bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, intestinal barrier damage (secondary changes in the intestinal microvasculature due to shock, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and direct injury), systemic immunosuppressed status [12, 13], hemorrhagic shock [14], acute pancreatitis, cirrhosis, obstructive jaundice, and abdominal surgery [15, 16]. In our cases, bacterial translocation associated with acute pancreatitis may have caused intestinal bacteria proliferation in ischemic and necrotic pancreatic tissues, which could have further amplified the inflammation.

Up to 10%–20% of patients with acute pancreatitis are associated with pancreatic necrosis, surrounding pancreatic tissue necrosis, or both, and when infection occurs in the necrotic tissue, the mortality rate reaches 20% to 30% [17]. In the past, open drainage was the first choice of treatment for emphysematous pancreatitis; however, in recent years, there have been cases of successful conservative treatment [18, 19], and percutaneous or endoscopic drainage has been reportedly associated with lower mortality than open drainage [20,21,22]. In general, infectious complications of pancreatitis generally occur > 2–3 weeks after the initial treatment [23]. Furthermore, since early surgery for severe necrotizing pancreatitis is associated with a worse prognosis, endoscopic or percutaneous drainage has been reportedly performed at 4 weeks post-onset of pancreatitis if the patient’s general condition is maintained with conservative treatment [17]. In other words, percutaneous or endoscopic local infection drainage after acute pancreatitis should be performed, except in the following situations—failure of conservative treatment or medical drainage, undeniable perforation of the gastrointestinal tract as a cause of emphysema, and complications of abdominal compartment syndrome. Further, Beger et al. reported a 24% bacterial contamination rate of necrotic material in patients operated on during the first 7 days after the onset of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, suggesting that infection may be complicated early during pancreatitis [24]. In the general case of severe necrotizing pancreatitis, most patients have a severe course due to systemic inflammation associated with pancreatitis even after performing open surgical drainage. However, the retroperitoneal infection that was concomitant with acute pancreatitis was thought to greatly contribute to the disease severity in our cases. Therefore, early surgical drainage may have led to infection control. Hence, drainage procedures aimed at early removal of infected tissues may be effective even in pancreatitis.

A Pubmed search for the keywords “Emphysematous”, “Pancreatitis”, “Gas”, and “Air” over a 20-year period from 1992 to 2021 identified 58 reports of acute pancreatitis with emphysema, which were reviewed in 60 patients, including these two patients (Table 1). The median age was 61 years, comprising 46 males, 12 females, and 2 of unknown sex. The prevalence of diabetes and history of alcohol consumption was lower than in previous reports; age could be a risk factor, since the median age in the analysis of 60 cases was 61. In our review, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were most frequently detected bacteria in the peripancreatic area, but the clinical course did not differ depending on the organisms detected. There were 12 cases in which positive blood cultures were observed; however, the exact rate of positive blood cultures was unknown since most of the previous reports did not indicate it. A total of 20 patients underwent laparotomy, 13 underwent percutaneous or endoscopic drainage therapy, 4 patients underwent both laparotomy and drainage therapy, and 22 underwent conservative treatment. Then, 17 of 60 patients died, for an overall mortality rate of 27%, similar to previous reports on mortality rates caused by necrotizing pancreatitis [66]. However, 34 (56.7%) patients had < 1 week between the onset of pancreatitis and the occurrence of emphysema, and 15 of these patients died. The mortality rate was as high as 44.1%, and the early occurrence of emphysema was a particularly serious condition. Most of the 15 patients who developed emphysema within a week of disease onset died from multiple organ failures. Thus, the early onset of acute pancreatitis with emphysema may lead to rapid disease progression. Although the causes of retroperitoneal emphysema range from severe to benign diseases, infection associated with emphysema may be rapidly progressing to necrotizing infection, as in gas gangrene. Moreover, in these clinical situations, conservative treatment and percutaneous or endoscopic drainage may be preceded by surgical treatment; however, we should not hesitate to resort to surgical treatment to ensure adequate drainage.

Conclusions

Necrotizing pancreatitis complicated by emphysema is an extremely severe acute pancreatitis. In this study, two patients had severe necrotizing pancreatitis with retroperitoneal emphysema. In both patients, peripancreatic drainage including retroperitoneal space was successful. When emphysema is observed early in acute pancreatitis, the disease may progress rapidly; therefore, surgical treatment such as open drainage should be selected.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Wig JD, Kochhar R, Bharathy KG, Kudari AK, Doley RP, Yadav TD, et al. Emphysematous pancreatitis Radiological curiosity or a cause for concern? JOP. 2008;9:160–6.

Bul V, Yazici C, Staudacher JJ, Jung B, Boulay BR. Multiorgan failure predicts mortality in emphysematous pancreatitis: a case report and systematic analysis of the literature. Pancreas. 2017;46:825–30.

Dewachter P, Savic L. Perioperative anaphylaxis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management. BJA Educ. 2019;19:313–20.

Watts RA, Isenberg DA. Pancreatic disease in the autoimmune rheumatic disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1989;19:158–65.

Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Cholesterol crystal embolization to liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1819–22.

Orvar K, Johlin FC. Atheromatous embolization resulting in acute pancreatitis after cardiac catheterization and angiographic studies. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1755–61.

Fernández-del Castillo C, Harringer W, Warshaw AL, Vlahakes GJ, Koski G, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Risk factors for pancreatic cellular injury after cardiopulmonary bypass. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:382–7.

Warshaw AL, O’Hara PJ. Susceptibility of the pancreas to ischemic injury in shock. Ann Surg. 1978;188:197–201.

Haffar S, Kaur RJ, Garg SK, Hyder JA, Murad MH, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. Acute pancreatitis associated with intravenous administration of propofol: evaluation of causality in a systematic review of the literature. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2019;7:13–23.

Grayson DE, Abbott RM, Levy AD, Sherman PM. Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2002;22:543–61.

Balzan S, de Almeida QC, de Cleva R, Zilberstein B, Cecconello I. Bacterial translocation: overview of mechanisms and clinical impact. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:464–71.

Berg RD. Bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:149–54.

Ding LA, Li JS. Gut in diseases: physiological elements and their clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2385–9.

Nadler EP, Ford HR. Regulation of bacterial translocation by nitric oxide. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:165–8.

Wilmore DW, Smith RJ, O’Dwyer ST, Jacobs DO, Ziegler TR, Wang XD. The gut: a central organ after surgical stress. Surgery. 1988;104:917–23.

Carrico CJ, Meakins JL, Marshall JC, Fry D, Maier RV. Multiple-organ-failure syndrome. Arch Surg. 1986;121:196–208.

Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update: management of pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:67-75.e1.

Nadkarni N, D’Cruz S, Kaur R, Sachdev A. Successful outcome with conservative management of emphysematous pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:242–5.

Kvinlaug K, Kriegler S, Moser M. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a less aggressive form of infected pancreatic necrosis? Pancreas. 2009;38:667–71.

Ku YM, Kim HK, Cho YS, Chae HS. Medical management of emphysematous pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:455–6.

van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–502.

Karakayali FY. Surgical and interventional management of complications caused by acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13412–23.

Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Makary MA, Mostafavi A, McGrath D, Warshaw AL. Débridement and closed packing for the treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1998;228:676–84.

Beger HG, Bittner R, Block S, Büchler M. Bacterial contamination of pancreatic necrosis. A prospective clinical study. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:433–8.

Sánchez-Gollarte A, Jiménez-Álvarez L, Pérez-González M, Vera-Mansilla C, Blázquez-Martín A, Díez-Alonso M. Clostridium perfringens necrotizing pancreatitis: an unusual pathogen in pancreatic necrosis infection. Access Microbiol. 2021;3: 000261.

Lee SH, Paik KH, Kim JC, Park WS. Percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy in a patient with emphysematous pancreatitis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100: e27905.

Sandhu S, Alhankawi D, Chintanaboina J, Prajapati D. Emphysematous pancreatitis mimicking bowel perforation. ACG Case Rep J. 2021;8: e00641.

Ramírez Esteso F, Domínguez Ferreras E, Domper Bardají F, Rodríguez GM. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a rare entity with characteristic radiological findings. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021;113:721–2.

Pimentel R, Almeida N, Figueiredo P. Endoscopic necrosectomy—when the gastroenterologist faces his greatest nightmare. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021. https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2021.8403/2021.

Borao Laguna C, Martínez Domínguez SJ, Saura Blasco N, Hernández Ainsa M, García Mateo S, Velamazán Sandalinas R, et al. Emphysematous pancreatitis: clinical course and management. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:71–2.

Ishii Y, Tsuchiya A, Hayashi K, Terai S. Pancreas gas gangrene caused by klebsiella pneumoniae. Intern Med. 2020;59:2963–4.

Page D, Ratnayake S. A rare case of emphysematous pancreatitis: managing a killer without the knife. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020(6):rjaa086.

Niryinganji R, Mountassir C, Siwane A, Tabakh H, Touil N, Kacimi O, et al. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a rare complication of acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7: 001550.

Bhattacharjee U, Saroch A, Pannu AK, Wadhera S. Emphysematous pancreatitis. QJM. 2020;113:127–8.

Martínez D, Belmonte MT, Kośny P, Ghitulescu MA, Florencio I, Aparicio J. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a rare complication. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2018;5: 000955.

Junquera-Olay S, Baleato-González S, García-Figueiras R. Fatal pancreatic inflammation: extensive emphysematous pancreatitis diagnosed by computed tomography. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2019;84:398–9.

Xi Terence LY, Jia GY, Madhavan K. Fulminant emphysematous pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:A32.

Tana C, Silingardi M, Giamberardino MA, Cipollone F, Meschi T, Schiavone C. Emphysematous pancreatitis associated with penetrating duodenal ulcer. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8666–70.

Schattner A, Drahy Y, Dubin I. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Am J Med. 2017;130:e499-500.

Alonso Calderón E, Pérez González C, Prieto Calvo M, Marquina TT. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Fulminant course. Cir Esp. 2017;95:611.

Balani A, Dey AK, Sarjare S, Chatur C. Emphysematous pancreatitis: classic findings. BMJ Case Rep. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-217445.

Hamada S, Shime N. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1075.

Robert B, Chivot C, Yzet T. Emphysematous pancreatitis. A rare cause of fulminant multiorgan failure. Presse Med. 2015;44:572–3.

Samanta S, Samanta S, Banik K, Baronia AK. Emphysematous pancreatitis predisposed by Olanzapine. Indian J Anaesth. 2014;58:323–6.

Romera Barba E, Torregrosa Pérez N, García Marcilla JA, Vázquez Rojas JL. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Cir Esp. 2014;92: e1.

Riaño Molleda M, González Andaluz M, González Noriega M, Castillo SF. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Cir Esp. 2013;91: e59.

Okamoto H, Kuriyama A. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:396.

Komatsu H, Yoshida H, Hayashi H, Sakata N, Morikawa T, Onogawa T, et al. Fulminant type of emphysematous pancreatitis has risk of massive hemorrhage. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2011;4:249–54.

Porter NA, Lapsia SK. Emphysematous pancreatitis: a severe complication of acute pancreatitis. QJM. 2011;104:897.

Esparza L, Díaz AI, Anguiano MP. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Med Intensiva. 2012;36:65.

Sodhi KS, Lal A, Vyas S, Verma S, Khandelwal N. Emphysematous pyelonephritis with emphysematous pancreatitis. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:e85–7.

Choi HS, Lee YS, Park SB, Yoon Y. Simultaneous emphysematous cholecystitis and emphysematous pancreatitis: a case report. Clin Imaging. 2010;34:239–41.

Garrido F, Sancho E, Gasz A, Menéndez Sanchez P, Gambí PD. Pneumoperitoneum secondary to spontaneous gaseous gangrene of the pancreas due to Klebsiella sp. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;32:585–6.

Kamei K, Takeyama Y, Yasuda T, Kawasaki M, Ueda T, Ohyanagi H, et al. Early infection of peripancreatic tissue in mild acute pancreatitis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2009;39:1083–5.

Camps I, Arméstar F, Cuadrado M, Mesalles E. VAC (vacuum-assisted closure) “covered” laparostomy to control abdominal compartmental syndrome in a case of emphysematous pancreatitis. Cir Esp. 2009;86:250–1.

Guardado AV, Vicente VP, Pordomingo AF, Cerdeña MT, Delgado AÁ, Garrido AS, et al. Emphysematous pancreatitis: Conservative or surgical treatment? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;32:605–9.

De Silva NM, Windsor JA. Clostridium perfringens infection of pancreatic necrosis: absolute indication for early surgical intervention. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:757–9.

Ikegami T, Kido A, Shimokawa H, Ishida T. Primary gas gangrene of the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:80–1.

Bazan HA, Kim U. Images in clinical medicine. Emphysematous pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349: e25.

Birgisson H, Stefánsson T, Andresdóttir A, Möller PH. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:918–20.

McCloskey M, Low VH. CT of pancreatic gas gangrene. Australas Radiol. 1996;40:75–6.

Daly JJ Jr, Alderman DF, Conway WF. General case of the day. Emphysematous pancreatitis. Radiographics. 1995;15:489–92.

Sadeghi-Nejad H, O’Donnell KF, Banks PA. Spontaneous gas gangrene of the pancreas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;18:136–8.

Morris DL, Wilkinson LS, Al-Mokhtar N. Case report: emphysematous tuberculous pancreatitis diagnosis by ultrasound and computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 1993;48:286–7.

Ghidirim G, Gagauz I, Mişin I, Guţu E, Vozian M. Emphysematous necrotizing pancreatitis. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2005;100:293–6.

Trikudanathan G, Wolbrink DRJ, van Santvoort HC, Mallery S, Freeman M, Besselink MG. Current concepts in severe acute and necrotizing pancreatitis: an evidence-based approach. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1994-2007.e3.

Acknowledgements

We thank Enago for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

We declare that no authors received funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KC drafted the manuscript. KC, KI, YS, NK, HM, TM, TW, HY, HN, DI, AK, DK, AI, AN, DK, and KH determined the treatment plan. KI supervised the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate in this study were carried out following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chida, K., Ishido, K., Sakamoto, Y. et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis complicated by retroperitoneal emphysema: two case reports. surg case rep 8, 183 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01542-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01542-2