Abstract

Background

Suture granuloma with hydronephrosis after abdominal surgery is extremely rare. We herein report a successfully treated case of suture granuloma with hydronephrosis caused by ileostomy closure after rectal cancer surgery.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old male underwent laparoscopic low anterior resection with covering ileostomy. Two months after primary operation, ileostomy closure was performed with two layered hand-sewn suture (Albert–Lembert method) using absorbable suture. In that operation, marginal blood vessels in the mesentery were ligated with silk suture. The patient had remained in remission with no evidence of tumor recurrence, however, 2 years and 5 months after primary surgery, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass-forming lesion on the right external iliac artery (43 × 26 mm) and hydronephrosis. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) showed a mass-forming lesion without high accumulation, which obstructed the right ureter. Recurrence could not be ruled out due to the rapid appearance of tumor and hydronephrosis in the short-term period. Thus, the patient underwent laparotomy. The tumor located in the mesentery near the anastomosis of ileostomy closure and it was strongly adherent to the retroperitoneum, which obstructed the right ureter. The adhesion between the tumor and ureter was carefully dissected and tumor resection with partial small bowel resection was then performed with preservation of the ureter using ureteral stents. Pathological examination of the tumor revealed fibrous proliferation of foreign body granuloma. In the resected tumor, sutures with foreign giant cells were found. Therefore, we diagnosed the tumor as silk suture granuloma, which was caused by the silk suture used to ligate blood vessels of the mesentery at the ileostomy closure. The patient remained well with no evidence of tumor recurrence as 5 years after the primary operation of rectal cancer.

Conclusions

Suture granuloma is a rare surgery-related complication in the postoperative surveillance of patients with colorectal cancer. If suture granuloma mimicking local recurrence is a differential diagnosis, it would be important to consider to avoid unnecessary extended resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Foreign body granuloma is a rare benign tumor, which is induced by medical materials several months or years after surgery [1]. Particularly, suture is well recognized as one of the major causes of granuloma [2]. In cases of post-surgery of malignant tumors, to differentiate suture granuloma from recurrence or metastasis is critically important for appropriate treatment.

Hydronephrosis is one of the suggestive of recurrence, which can be caused by lymph node metastasis or peritoneal recurrence in patients who underwent colorectal cancer surgery [3]. It is very rare that suture granuloma developed hydronephrosis after rectal cancer surgery.

We herein report a successfully treated case of suture granuloma with hydronephrosis by tumor resection.

Case presentation

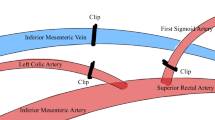

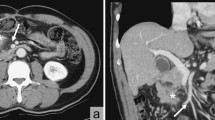

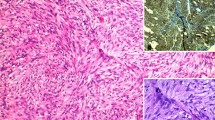

A 63-year-old male was admitted to undergo colonoscopy for the evaluation of blood feces. The patient underwent endoscopic resection for a type Isp polyp of the lower rectum. The pathological diagnosis examination revealed well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with submucosal layer (2500 µm) invasion and lymphatic infiltration (ly1). The patients underwent laparoscopic low anterior resection with covering ileostomy as additional resection. The pathological examination of surgical specimen revealed there was no lymph node metastasis, resulting in pStage I. Two months after primary operation, ileostomy closure was performed with two layered hand-sewn suture (Albert–Lembert method) using absorbable suture. In that operation, marginal blood vessels in the mesentery were ligated with silk suture. After ileostomy closure, the patient had been followed by a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) every 6 months and tumor marker every 3 months, and remained in remission with no evidence of tumor recurrence. However, 2 years and 5 months after the operation, CT showed a mass-forming lesion on the right external iliac artery (43 × 26 mm) (Fig. 1A) and hydronephrosis (Fig. 1B). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) showed a mass-forming lesion without high fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) accumulation (Fig. 1C), which obstructed the right ureter (Fig. 1D). Tumor markers were as follows: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 3.6 ng/ml; carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) 3.0 U/ml and there were no findings suggestive of metastasis nor recurrence in other organs. Although PET/CT findings and tumor marker were not positive, recurrence could not be ruled out due to the rapid appearance of tumor and hydronephrosis in the short-term period. Thus, the patient underwent laparotomy. The tumor was observed in the mesentery near the anastomosis of ileostomy closure and it was strongly adherent to the retroperitoneum, which obstructed the right ureter (Fig. 2). The adhesion between the tumor and ureter was carefully dissected and tumor resection with preservation of the ureter using ureteral stents. After tumor resection, partial small bowel resection was performed due to disturbance of mesenteric blood flow. The resected specimens revealed a mass-forming lesion surrounded the right ureter (Fig. 3A). Pathological examination of the tumor revealed dense fibrous proliferation and lymphatic follicles with germinal centers (Fig. 3B, C). In the resected tumor, sutures with foreign giant cells were found (Fig. 3C, D). Therefore, we diagnosed the tumor as suture granuloma, which was caused by the silk suture using to ligate blood vessels in mesentery at the ileostomy closure. After operation, the patient was discharged on postoperative day 14 without any complications. The patient remained well with no evidence of tumor recurrence as 5 years after the primary operation of rectal cancer.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass-forming lesion on the right external iliac artery (43 × 26 mm) (A arrow, B arrow) and hydronephrosis (B arrowhead). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) showed a mass-forming lesion without high accumulation (C arrow), which obstructed the ureter (D arrow)

Resected specimen and pathological examination. The resected specimens revealed a mass that had surrounded the right ureter (A arrow). Pathological examination of the tumor revealed dense fibrous proliferation (B) and lymphatic follicles with germinal centers (C arrow). In the partially resected tumor, sutures with foreign giant cells were found (C arrowhead, D)

Discussion

Suture granulomas are caused by persistent foreign body reactions to suture material due to their antigenicity and/or presence of bacterial infection in the fibers of silk [4, 5]. Silk sutures are non-absorbable yarn which show a particularly high incidence of granuloma formation of 0.6–7.1% [6, 7]. Because suture granuloma often grows rapidly in the short-term period [8, 9], differentiating from recurrent tumors after surgery of malignant tumors is difficult in postoperative malignancy surveillance [8, 9]. Suture granuloma has shown false positive on PET/CT in 70–80% of granuloma cases due to the rapid growth of the granulomas caused by inflammatory response [8]. In the current case, PET/CT did not show high FDG accumulation. The reason of negative findings might be that PET/CT was performed when the inflammatory activity was low. In cases of granuloma, the result on PET/CT may depend on the timing of tumor growth unlike malignant tumors. In addition, the granuloma that causes external compression of adjacent organs is extremely rare. Although there have been a few reports of anastomotic suture granulomas that obstructed the lumen of ureter or bronchus [10, 11], extramural compression by suture granuloma has not been well-described. Unlike malignant tumors, granuloma is often non-invasive [12, 14], therefore, in the current case, although the suture granuloma involved the right ureter, careful resection enabled to preserve ureter. Thus, if granuloma is a differential diagnosis, it would be important to consider to avoid unnecessary extended resection.

As to the granuloma after colorectal cancer surgery, seven case reports have been published in the English literature; details of the current case and the other seven cases are summarized in Table 1 [8, 12,13,14,15,16]. Only one patient (Case 2) among them had hydronephrosis by granuloma in the right pelvic side peritoneum 2 years and 6 months later after rectal cancer surgery [12]. There have been no reports of granuloma with hydronephrosis in the other pelvic surgery. In the reports on colorectal cancer, the most frequent causal material was suture (five patients), followed by metal staple, clip and food residues. In the current case, the suture granuloma was developed from the silk suture that was used at the time of ileostomy closure.

In colorectal cancer surgery, silk suture has been reported to develop surgical site infection more frequently compared to absorbable suture [17]. In addition, the occurrence rates of granuloma by silk suture have been higher than those by absorbable suture [7]. In the present era of modern surgical practice, the use of silk sutures is decreasing and is even rarer in laparoscopic surgery. However, it should be noted that silk sutures used to ligate blood vessels may be risks of granuloma occurring in traditional open surgery or extra-abdominal procedures of laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, silk sutures should be avoided if possible, considering the higher incidence of surgical site infection as well as suture granuloma.

Conclusions

We reported to our knowledge the case of suture granuloma with hydronephrosis caused by ileostomy closure after rectal cancer surgery.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusion of this article is included within the article.

Abbreviations

- CIA:

-

Common iliac artery

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EIA:

-

External iliac artery

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- IIA:

-

Internal iliac artery

- PET/CT:

-

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

References

Luijendijk RW, de Lange DC, Wauters CC, Hop WC, Duron JJ, Pailler JL, et al. Foreign material in postoperative adhesions. Ann Surg. 1996;223:242–8.

Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497–523.

Brown G, Drury AE, Cunningham D, Husband JE. CT detection of hydronephrosis in resected colorectal cancer: a predictor of recurrent disease. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:137–42.

Geiger D, Debus ES, Ziegler UE, Larena-Avellaneda A, Frosch M, Thiede A, et al. Capillary activity of surgical sutures and suture-dependent bacterial transport: a qualitative study. Surg Infect. 2005;6:377–83.

Tang L, Eaton JW. Inflammatory responses to biomaterials. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:466–71.

Nagar H. Stitch granulomas following inguinal herniotomy: a 10-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1505–7.

Iwase K, Higaki J, Tanaka Y, Kondoh H, Yoshikawa M, Kamiike W. Running closure of clean and contaminated abdominal wounds using a synthetic monofilament absorbable looped suture. Surg Today. 1999;29:874–9.

Matsuura S, Sasaki K, Kawasaki H, Abe H, Nagai H, Yoshimi F. Silk suture granuloma with false-positive findings on PET/CT accompanied by peritoneal metastasis after colon cancer surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:22–5.

Lim JW, Tang CL, Keng GH. False positive F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose combined PET/CT scans from suture granuloma and chronic inflammation: report of two cases and review of literature. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2005;34:457–60.

Scheidler DM, Foster RS, Bihrle R, Scott JW, Litwiller SE. Anastomotic suture granuloma following radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1990;143:133–4.

Jiao Y, Shang Y, Li Q, Wang Y, Wu N, Wang Q, et al. Foreign body granulomas in the left main bronchus resulting from the sutures for esophageal cancer surgery: the report of two cases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:2764–7.

Kim SW, Shin HC, Kim IY, Baek MJ, Cho HD. Foreign body granulomas simulating recurrent tumors in patients following colorectal surgery for carcinoma: a report of two cases. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:313–8.

Asano E, Furuichi Y, Kumamoto K, Uemura J, Kishino T, Usuki H, et al. A case of Schloffer tumor with rapid growth and FDG-PET positivity at the port site of laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for colon cancer. Surg Case Rep. 2019;23:116.

Nihon-Yanagi Y, Ishiwatari T, Otsuka Y, Okubo Y, Tochigi N, Wakayama M, et al. A case of postoperative hepatic granuloma presumptively caused by surgical staples/clipping materials. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:90.

Crucitti A, Grossi U, Leccisotti L, Maggi F, Ricci R, Mazzari A, et al. Food residue granuloma mimicking metastatic disease on FDG-PET/CT. Jpn J Radiol. 2013;31:349–51.

Huang SF, Chiang CL, Lee MH. Suture granuloma mimicking local recurrence of colon cancer after open right hemicolectomy: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2021;7:164.

Watanabe A, Kohnoe S, Sonoda H, Shirabe K, Fukuzawa K, Maekawa S, et al. Effect of intra-abdominal absorbable sutures on surgical site infection. Surg Today. 2012;42:52–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YT and KH were responsible for the study concept, data collection, and writing the paper. The other authors collected data, reviewed and corrected the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takano, Y., Haruki, K., Tsukihara, S. et al. Suture granuloma with hydronephrosis caused by ileostomy closure after rectal cancer surgery: a case report. surg case rep 7, 210 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01303-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01303-7