Abstract

Background

The arcuate line is the inferior margin of the posterior layer of rectus abdominis sheath. An arcuate line hernia is a parietal interstitial hernia consisting of ascending protrusion of intraperitoneal contents above the arcuate line. Arcuate line hernias are rare, and fewer than 20 cases undergoing surgical repair have been reported. Various surgical approaches were used in previous cases, and there is no consensus regarding the ideal repair method. We report the first case of an arcuate line hernia repaired using single-incision laparoscopic surgery.

Case presentation

The patient was a 78-year-old man who presented with a history of intermittent lower abdominal quadrant pain of more than 2 month’s duration. He had not previously undergone abdominal surgery, but had a history of mycobacterial lung disease and asthma. His vital signs were normal on presentation, and he experienced no vomiting or nausea. On palpation, his abdomen was flat and soft, and no mass was palpable. However, there was slight tenderness in the right lower quadrant. Blood laboratory test results were within normal ranges. Computed tomography revealed small bowel protrusion between the rectus abdominis and the posterior rectus sheath, and an arcuate line hernia was suspected and subsequently confirmed intraoperatively. The patient underwent single-incision laparoscopic repair with the intraperitoneal onlay mesh technique with tacks and with care to avoid the inferior epigastric vessels. The operation time was 30 min, and no intra- or post-operative complications occurred. Surgery relieved his symptoms, with no recurrence within 1 year postoperatively.

Conclusions

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery was performed easily and successfully in this rare patient with arcuate line hernia. Arcuate line hernia should be considered in patients presenting with abdominal symptoms, and single-incision laparoscopic repair should be considered for repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The arcuate line (AL), also called the linea arcuata, linea semicircularis, and the semicircular line of Douglas, marks an anatomical transition point inferior to which all the aponeurotic layers of the abdominal muscles, except the transversalis fascia, pass simultaneously anterior to the rectus abdominis muscle [1, 2]. The arcuate line is the inferior margin of the posterior rectus sheath (PRS). At the caudal side of the AL, the posterior side of the rectus abdominis muscle is covered only by the transversalis fascia and the peritoneum as the areolar tissue layer (Fig. 1). An arcuate line hernia (ALH) is a protrusion of intraperitoneal structures above the PRS, with the hernia orifice between the AL and the rectus abdominis. ALH is generally categorized as an internal or intraparietal hernia, as there is no true abdominal wall defect [3]. This rare type of hernia was first reported by Cappeliez et al. [3] and there have been fewer than 20 reported cases of surgery for ALH to date [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Surgical management of ALH comprises open or laparoscopic repair, with or without a mesh. We performed single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) for the first time for ALH. The hernia was repaired using the intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) technique, and the operation was performed safely and easily; therefore, we report SILS as a useful method.

Diagram of the anterior abdominal wall. a The right rectus abdominis muscle, external oblique muscle, and internal oblique muscle were resected. b Section above the arcuate line. c Section below the arcuate line. 1 Rectus abdominis muscle, 2 skin, 3 Scarpa’s fascia, 4 external oblique muscle, 5 internal oblique muscle, 6 transverse abdominis muscle, 7 transversalis fascia, 8 peritoneum, 9 aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, 10 aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle, 11 aponeurosis of the transverse abdominis muscle, 12 inferior epigastric vessels, 13 posterior layer of the rectus abdominis, 14 arcuate line, 15 semilunar line

Case presentation

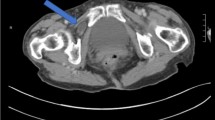

The patient was a 78-year-old man who presented to our hospital with a chief complaint of intermittent right lower abdominal quadrant pain for over 2 months. His medical history included nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease and asthma, and he had no history of abdominal surgery. He had neither nausea nor vomiting, and his vital signs were normal. His height was 162.2 cm, weight was 72 kg, and body mass index (BMI) was 27.4 kg/m2. His abdomen was soft and flat, no parietal mass was palpated, and slight tenderness was present in the right lower quadrant. Blood test results were within normal limits. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed protrusion of a small bowel loop between the rectus muscle and the PRS (Fig. 2); ALH was suspected. Laparoscopic surgery was planned, and SILS was chosen to minimize the invasiveness.

With the patient in the supine position under general anesthesia, a 2-cm-long muscle-splitting incision was made at contralateral McBurney’s point. A Lap Protector™ (Hakko, Nagano, Japan) was attached to the wound, and an EZaccess™ (Hakko) with three inserted 5-mm trocars was added (Fig. 3a). Laparoscopically, the ALH was easily detected, and there were no hernia contents (Fig. 3b). We used the IPOM technique for its simplicity and repair reliability. A 9-cm-diameter Symbotex™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) composite mesh was positioned so that the AL was pressed against the rectus abdominis muscle, and the mesh was fixed using AbsorbaTack™ (Medtronic) tacks while percutaneously compressing from the opposite side. The first few tacks were fixed using a Diamond-Flex® circular retractor (BD, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) to stabilize the mesh position, and the final 30 tacks were fixed using the double-crown technique (Fig. 3c and d). We fixed the mesh carefully to avoid damaging the inferior epigastric vessels. Seprafilm® (Sanofi, Paris, France) was placed under the incision to prevent adhesions, and the wound was sutured in layers. The operation time was 30 min. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged on the third post-operative day. His symptoms resolved after surgery, and no recurrence has been noted 1 year since the surgery.

Operative findings: a location of the hernia (1) and skin incision (2). b The arrow indicates the cranial side. The hernia (3) is above the arcuate line (4) and lies along the inferior epigastric vessels (5). c The first tack to fix the mesh involved using the Diamond-Flex® circular retractor to stabilize the mesh position. d The mesh is secured using the double-crown method

Discussion

In the supraumbilical and part of the infraumbilical abdominal wall, the rectus abdominis muscle is covered on the dorsal side by the PRS, a plate of aponeurotic tissue that is formed by the fascia transversalis and posterior lamina of the internal oblique muscle. Somewhere between the umbilicus and pubic bone, the posterior lamina of the internal oblique muscle joins the anterior lamina on the ventral side of the rectus muscle, leaving only the transversus fascia on the dorsal side as areolar tissue [17]. This level is called the AL. In other words, the AL can be described as the inferior margin of the PRS. The level of the AL varies. According to a cadaveric study by Loukas et al. the AL was located a mean of 2.1 ± 2.3 cm superior to the level of the anterior superior iliac spines [2]. It is thought that ALHs form by the folding of the peritoneum and the transversus fascia between the dorsal transversus abdominis and the PRS. ALH is classified as an internal hernia because there is no true defect in the abdominal wall [3]. The ALH orifice is wide, and Montgomery et al. described it as ‘the top of a mitten’ [12]. Therefore, abdominal organs are able to move in and out of the hernia easily, which may have caused the intermittent symptoms described by our patient.

In some cases, the preoperative diagnosis of ALH was mistaken for Spigelian hernia [3, 12]. Spigelian hernias are located at the level of the semilunar line where the fasciae of the oblique and transversus muscles begin to split into separate layers of the abdominal musculature. Spigelian hernias account for 1%–2% of abdominal wall hernias [18]. The majority occur within the ‘Spigelian hernia belt’, which is the 6-cm area of the Spigelian aponeurosis that lies cephalad to the interspinal plane [19]. Spigelian hernias often have a narrow fascial defect and, therefore, have an increased risk of incarceration and strangulation [20]. Both ALH and Spigelian hernia occur at a similar level, but the position of the hernia portal is slightly lateral in Spigelian hernias compared with ALH (Fig. 4). Knowledge of both hernias is the key to diagnosis.

The prevalence of ALH is unclear, and the underlying reason is that most ALHs are asymptomatic and remain unclassified, and the diagnosis is often incidental or could be misclassified as another abdominal hernia. To investigate the incidence of ALH, two retrospective large cohort studies using CT have been reported [17, 21]. Courier et al. retrospectively analyzed a continuous series of 315 unselected patients and classified AL abnormalities. A delineation of the AL with minimal bulging of intraperitoneal fat was classified as grade 1 (G1). Grade 2 (G2) herniation was defined as a minimal but substantial true herniation of fat and/or intestinal loops under the AL. Grade 3 (G3) was defined as a clear prominent herniation of abdominal structures (omental fat and/or bowel); G2 and G3 were defined as ALH. In the series, AL abnormality (G1, G2, and G3) was found in 8.57% of the patients, and actual ALH (G2, G3) was found in 1.62% of the patients. The prevalence of AL abnormality (G1, G2, and G3) is higher in men, with a reported M:F ratio of 12.5:1 [21]. Bloemen et al. [17] retrospectively analyzed 415 patients who presented to the emergency department for surgical consultation with abdominal complaints and who underwent CT but did not have a definitive diagnosis. ALH was classified according to the definition of Courier et al. In the series, AL abnormality was found in 11.3% of the patients, and actual ALH was found in 3.4% of the patients. The rate of AL abnormality was equally divided among men and women. Patients with ALH were found to have a significantly higher BMI when compared with patients without ALH. Diabetes mellitus and the presence of an aneurysm of the abdominal aorta were also seen more often in patients with ALH. Among patients with ALH, correlation with clinical complaints was found in half of the patients [17]. The results of these two studies suggest that it is important to suspect ALH in patients with abdominal complaints.

There have been 19 reported cases of surgery for AL (Table 1) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Unexpectedly, the ratio of men to women was 8:11; slightly more women than men. Three cases occurred after abdominal surgery and were diagnosed as incisional hernias, but were diagnosed as ALH intraoperatively [4, 15, 16]. As previously mentioned, ALH is considered less likely to cause symptoms because of the wide hernia orifice; however, there have been cases of emergency surgery owing to incarceration [6, 9, 13]. Although ALH is a rare and little-known disease, these cases suggest that surgeons should be aware of the condition.

Laparoscopic surgery was performed in several cases, and is recommended for several reasons. The diagnostic properties of laparoscopy are superior, making it possible to diagnose concomitant hernias that could be addressed during the same operation, and for excluding other diagnoses, especially in emergency surgery. Laparoscopy also enables inspecting the contents of the hernia sac. It is also considered possible that asymptomatic ALH may be found during laparoscopic surgery for other diseases. Whether asymptomatic ALH needs to be repaired is a matter of debate. In reported cases, the methods of hernia repair comprised direct suture, trans-abdominal preperitoneal repair (TAPP), and extended-view totally extraperitoneal repair (eTEP). There have been no reports of recurrence. It is difficult to determine the best method because each technique has advantages and disadvantages. It is best to use the method that the surgeon is comfortable with. In any method, care must be taken to avoid damaging the inferior epigastric vessels that branch from the external iliac vessels and cross the AL into the rectus abdominis. In our case, we performed SILS using the IPOM technique. The procedure was relatively simple, and we were able to close the hernia orifice safely and securely. The advantages of SILS are reduced associated morbidity, namely wound infection, pain, bleeding, visceral injury, and port-site herniation [22]. In light of the above, SILS should be considered an option for ALH.

Conclusion

We reported the first case of SILS for ALH. Although ALH is a rare disease, its possibility should be considered in patients with abdominal complaints. Laparoscopy is recommended for symptomatic ALH, and SILS should be considered.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ALH:

-

Arcuate line hernia

- AL:

-

Arcuate line

- PRS:

-

Posterior rectus sheath

- SILS:

-

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery

- IPOM:

-

Intraperitoneal onlay mesh

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Rizk NN. The arcuate line of the rectus sheath–does it exist? J Anat. 1991;175:1–6.

Loukas M, Myers C, Shah R, Tubbs RS, Wartmann C, Apaydin N, et al. Arcuate line of the rectus sheath: clinical approach. Anat Sci Int. 2008;83:140–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-073X.2007.00221.x.

Cappeliez O, Duez V, Alle JL, Leclercq F. Bilateral arcuate-line hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:864–5. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800864.

Vincelli V, Marazzi C, Posabella A, Steiger A. Linea arcuate hernia disguised as Pfannenstiel incision’s hernia: a case report and a systemic literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017(1):rjw230. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw230.

Weimer S, Cocco D, Ballecer C. Robotic transabdominal preperitoneal repair of bilateral arcuate line hernias. Greenville Health Syst Proc. 2017;2:56–8.

Hugot M, Nicodème-Paulin E, Stolz A. Arcuate line hernia initially missed getting complicated: a case report. J Clin Case Rep. 2017;7:2. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7920.10001011.

Coulier B. Bilateral arcuate line hernia featuring the “ladybug’s elytra” sign. Diagn Interv Imag. 2019;100:387–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2018.12.002.

Berney CR. Hybrid laparoscopic/open mesh repair of combined bilateral arcuate line and ventral hernias. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;9:rjz268. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz268.

Bloemen A, Keijzers MJ, Konsten JLM, Aarts F, Vogelaar FJ. Internal herniation of the abdominal wall. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:575–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.2008.

von Meyenfeldt EM, van Keulen EM, Eerenberg JP, Hendriks ER. The linea arcuata hernia: a report of two cases. Hernia. 2010;14:207–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-009-0526-x.

Abasbassi M, Hendrickx T, Caluwé G, Cheyns P. Symptomatic linea arcuata hernia. Hernia. 2011;15:229–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0639-2.

Montgomery A, Petersson U, Austrums E. The arcuate line hernia: operative treatment and a review of the literature. Hernia. 2013;17:391–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-012-0982-6.

Verlynde G, Coulier B, Rubay R. Twisted parietal peritoneal lipomatous appendage incarcerated in a linea arcuata hernia: imaging findings. Diagn Intervent Imag. 2016;97:1201–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2015.09.008.

Kollias V, Cribb B, Ganguly T, Bierton C, Karatassas A. Laparoscopic enhanced view total extraperitoneal repair for rare and elusive arcuate hernia. ANZ J Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16858.

McCulloch IL, Mullens CL, Hardy KM, Cardinal JS, Ueno CM. Linea arcuate hernia following transversus abdominis release incisional hernia repair. Ann Plastic Surg. 2019;82:85–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000001671.

Messaoudi N, Amajoud Z, Mahieu G, Bestman R, Pauli S, Van Cleemput M. Laparoscopic arcuate line hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:e110–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828fa7a1.

Bloemen A, Kranendonk J, Sassen S, Bouvy ND, Aarts F. Incidence of arcuate line hernia in patients with abdominal complaints: radiological and clinical features. Hernia. 2019;23:1199–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-02067-8.

Bittner R, Bain K, Bansal VK, Berrevoet F, Bingener-Casey J, Chen D, et al. Update of Guidelines for laparoscopic treatment of ventral and incisional abdominal wall hernias (International Endohernia Society (IEHS)): part B. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3511–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06908-6.

Malazgirt Z, Topgul K, Sokmen S, Ersin S, Turkcapar AG, Gok H, et al. Spigelian hernias: a prospective analysis of baseline parameters and surgical outcome of 34 consecutive patients. Hernia. 2006;10:326–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-006-0103-5.

Rath A, Bhatia P, Kalhan S, John S, Khetan M, Bindal V, et al. Laparoscopic management of Spigelian hernias. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2013;6:253–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ases.12026.

Coulier B. Multidetector computed tomography features of linea arcuata (arcuate-line of Douglas) and linea arcuata hernias. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:397–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-007-0218-0.

Greaves N, Nicholson J. Single incision laparoscopic surgery in general surgery: a review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:437–40. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588411X590358.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jane Charbonneau, DVM, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TF and TK performed the diagnosis, surgery, general anesthesia, and perioperative management of the patient. TF was responsible for data collection and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukunaga, T., Kasanami, T. Single-incision laparoscopic repair for an arcuate line hernia: a case report. surg case rep 7, 196 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01281-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01281-w