Abstract

Background

Portal venous gas has been considered as a radiological sign requiring urgent operative intervention; however, the reports concerning portal venous gas associated with favorable outcome are recently increasing.

Case presentation

We describe a 9-month-old boy with acute onset high fever and vomiting. The ultrasonography demonstrated micro-gas bubbles continuously floating in the intrahepatic portal vein. Contrast-enhanced CT, performed 1 h later from echography, revealed a whirlpool sign suggesting an intestinal malrotation with midgut volvulus, but with no signs of residual intrahepatic gas. Operative findings showed a mild volvulus with neither congestion nor ischemic change of the twisted bowel. Detorsion and Ladd’s procedure were completed laparoscopically.

Conclusions

Transient portal venous gas bubbles may be generated even in the mild intestinal volvulus with no bowel ischemia. Ultrasonography can be a sensitive detector to visualize such small amounts of gas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Portal venous gas (PVG) has been a well-known radiological finding, suggesting a potentially severe underlying abdominal disease requiring urgent operative intervention that occurs both in pediatric and adult populations [1]. Recently, spread of advanced imaging techniques has resulted in increased reports concerning PVG associated with not only severe or lethal conditions but also benign ones or diagnosed at much earlier stages [2]. The most reported cases concerning PVG with intestinal malrotation are associated with bowel necrosis induced by midgut volvulus [1, 3,4,5,6,7]. We describe a rare case of intestinal malrotation with mild volvulus who was diagnosed with air bubbles floating in the intrahepatic portal vein detected by bedside emergency ultrasonography.

Case

A 9-month-old male infant weighing 8450 g presented to the primary care pediatrician with acute onset high fever, non-bilious vomiting, and continuous crying in a glum mood. He showed no bloody stool. On clinical examination, his abdomen was almost flat and it seemed that there is no apparent tenderness but he is crying constantly.

Blood investigations revealed no remarkable inflammation, and the white cell count was 7700/mm3 and CRP was 0.35 mg/dl (< 0.14) with normal coagulation parameters. Liver function tests showed mild transaminase elevations with ALT 57 U/L (10–42), AST 71 U/L (13–30), and normal level of total bilirubin 0.7 mg/dl (0.4–1.5). Blood urea was 3.5 mg/dl (< 20), and creatinine 0.26 mg/dl (< 1.07). Serum CK level was in the normal range with 237 U/L (59–248).

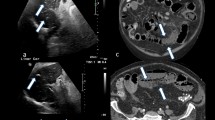

The plain X ray-film showed no sign of bowel obstruction, but the ultrasound demonstrated micro-gas bubbles continuously floating in the intrahepatic portal vein, suggesting any deteriorating clinical problems (Additional file 1: Video S1). The infant was emergently transferred to our department. On admission, he appeared with no acute distress and showed no irritability. Contrast-enhanced CT, performed 1 h later from echography, revealed a whirlpool sign (Fig. 1) at the right upper abdomen but with neither intrahepatic portal venous gas nor signs of pneumatosis intestinalis (Fig. 2a). Contrast upper gastrointestinal series showed a corkscrew sign of the jejunum, and additional contrast enema showed a cecum at the mid-upper abdomen (Fig. 2b). The preoperative evaluation was concerned for intestinal malrotation with midgut volvulus.

Additional file 1: Video S1. Abdominal Ultrasound. The micro-bubbles of gas were detected as highly echogenic particles flowing within the intrahepatic portal vein. (MPG 7968 kb)

Emergent laparoscopic operation was performed. The patient was placed in reverse Trendelenberg position. At a first laparoscopic glance, the cecum was located just under the liver at mid-abdomen (Fig. 3a). The small bowel showed a 180° clockwise volvulus, but with neither congestion nor ischemic signs. Using atraumatic bowel forceps, the small bowel was examined from distal ileum end to proximal with continuous spreading of the anterior mesentery surface in a stepwise fashion, ensuring no residual volvulus or local twists. After the complete volvulus reduction, the Ladd’s band (Fig. 3b) was divided (Fig. 3c) and the duodenum was mobilized with dissection of adhesions using SonoSurg™ ultrasonic surgical device (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For the separation of the duodenum and ileocecal region, mesentery was widened with dissection of interlaced thin ligaments on the anterior surface of mesentery. The gastrocolic ligament connecting Ladd’s band was additionally dissected to mobilize the right colon furthermore to the left (Fig. 3d). Appendectomy was added outside the umbilical porthole.

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged at the sixth postoperative day.

Discussion

In the pediatric population, the presence of hepatic portal venous gas (PVG) has been described in association with various disease processes such as necrotizing enterocolitis, gastroenteritis, following umbilical catheter, bowel obstruction, Hirschsprung’s disease, duodenal stenosis, SMA syndrome, and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis [1, 8].

There are four main theories that explain the pathophysiology of PVG: (1) bacterial—intramural gas-forming bacterial proliferation, (2) mechanical—increased intraluminal pressure during gastric or intestinal obstruction, (3) mucosal damage—air enters through disrupted mucosa, and (4) pulmonary disease—alveolar air dissects down through the mediastinum to the gastric wall [1]. In some cases, these factors appear to contribute in combination [2].

Intramural gas bubbles detected as pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) may be absorbed into the intestinal venous system, may travel into the portal vein, and can be localized as PVG by real-time ultrasound as flowing echogenic dots. Finally, PVG is trapped in the small branches of the portal vein inside the liver inducing dense granular echogenicities in hepatic parenchyma [3].

Reports of PVG as well as PI detected in the case of intestinal malrotation are rare, and the most reported cases showed intestinal necrosis that necessitated bowel resection and showed poor prognosis [1, 4,5,6,7].

In the present case, the micro-bubbles of gas were detected as highly echogenic particles flowing within the intrahepatic portal vein, and this become an opportunity for further evaluation and the intestinal malrotation was diagnosed. Operative findings showed a mild volvulus with neither congestion nor ischemic change of the twisted bowel. Raised intraluminal pressure or direct stimulation of the bowel wall induced by the volvulus might allow gas to infiltrate the bowel wall and mesentery portal venous flow. Therefore, PVG in this case appeared to be in a transient process that resolves within a short interval after spontaneous winding down or decompression of twisted bowels.

Recent literatures have stated that midgut volvulus in malrotation can be managed well in infants without deteriorating condition. The laparoscopic approach is feasible and effective for the case that even shows PVG, and should have the advantage of minimally invasive surgery with small incisional scar.

Conclusions

We reported a case of intestinal malrotation detected with air bubbles floating in the intrahepatic portal vein by ultrasonography. Transient portal venous gas bubbles may be generated even in the mild intestinal volvulus with no bowel ischemia. Sonography is very sensitive for PVG detection even with very small amounts of gas, and this sign could be one of the useful markers for detecting the early stage of volvulus.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that all data in this article are available within this published article.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PI:

-

Pneumatosis intestinalis

- PVG:

-

Portal venous gas

References

Arnon RG, Fishbein JF. Portal venous gas in the pediatric age group. Review of the literature and report of twelve new cases. J Pediatr. 1971;79:255–9.

Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, Doumit C. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3585–90.

Merritt CRB, Goldsmith JP, Sharp MJ. Sonographic detection of portal venous gas in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:1059–62.

Miskin M, Reilly BJ. Gas in the intestinal wall and portal venous system in infants. Can Med Assoc J. 1969;101:129–34.

Eggli KE, Loyer E, Anderson K. Neonatal pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis caused by volvulus of the mid intestine. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64:1189–90.

Yip CK, et al. Sonographic recognition of pneumatosis intestinalis and portal gas in an 11-months-old infant. Australas Radiol. 1990;34:169–71.

Bohnhorst B, et al. Portal venous gas detected by ultrasound differentiates surgical NEC from other acquired neonatal intestinal diseases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011;21:12–7.

Sharma R, Tepas JJ 3rd, Hudak ML, Wludyka PS, Mollitt DL, Garrison RD, Bradshaw JA, Sharma M. Portal venous gas and surgical outcome of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:371–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None of the authors have anything to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH, HK, TI, and KI determined the therapeutic strategy. NM, MI, and RM determined the diagnostic US. RH, HK, and KI performed the surgery, and contributed to the perioperative care. RH wrote the draft of the manuscript. AI revised the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

RH is a clinical professor of Fukuoka University Hospital and worked as a pediatric surgeon for more than 35 years.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirose, R., Kai, H., Inatomi, K. et al. Portal venous gas in intestinal malrotation with mild midgut volvulus. surg case rep 5, 141 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0700-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0700-z