Abstract

Background

Surgery for severe peritonitis often entails difficult wound closure and may require open abdominal management due to gut edema and/or concern of abdominal compartment syndrome. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is known to have good outcomes for wound closure after surgery for severe peritonitis. NPWT with continuous mesh fascial traction may result in even better outcomes, especially for fascial closure.

Case presentation

An 81-year-old man was hospitalized for abdominal pain. At admission, computed tomography (CT) demonstrated multiple liver metastases and a tumor perforating the sigmoid colon. Acute peritonitis due to perforated sigmoid colon cancer was diagnosed, and emergency peritonitis surgery and Hartmann’s operation were performed. However, at the end of the operation, the surgical abdominal wound could not be closed due to gut edema and concern of abdominal compartment syndrome. Thus, the abdominal wound was left open and NPWT was performed in the primary operation. In the second and subsequent operations, NPWT with mesh fascial traction was performed. The wound was ultimately closed in the fifth operation, which took place 9 days after the primary operation.

Conclusions

Treatment of severe peritonitis requires that gastroenterological surgeons learn some form of open abdominal management. This case suggests that NPWT with fascial mesh traction is a suitable solution. Furthermore, it does not require any special materials, and surgeons will find it easy to perform. In sum, NPWT with fascial mesh traction may be the preferred method of open abdominal management over other techniques currently available.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Surgery for severe peritonitis often entails difficult wound closure and may require open abdominal management because of gut edema and/or concern of abdominal compartment syndrome. Abdominal wounds that are difficult to close after emergency surgery should be managed via an open abdominal technique; however, the longer the wound remains open, the more difficult it will be to close because, in median laparotomy incisions, the rectal muscle in the wound shrinks laterally with time. To increase the success rate of wound closure surgery and avoid subsequent complications, various open abdominal methods have been developed [1,2,3,4]. These methods have become indispensable in emergency abdominal surgery and continue to be improved upon. In surgery for severe peritonitis, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is reported to result in good outcomes for wound closure [5]. Moreover, NPWT with continuous mesh fascial traction may have even better outcomes, especially for fascial closure [6,7,8]. Here, we present a case of severe peritonitis successfully treated by abdominal wound closure with NPWT and mesh fascial traction.

Case presentation

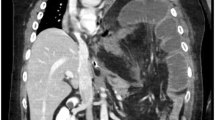

An 81-year-old man presented to our emergency department with abdominal pain that occurred after eating. At initial examination, the patient was alert but had difficulty standing due to significant abdominal distention and pain. His blood pressure was 118/68 mmHg with a regular pulse rate of 83 beats per minute. Laboratory test results included a white blood cell count of 3000/μL, hemoglobin concentration of 12.7 g/dL, platelet count of 241,000/μL, aspartate transaminase concentration of 177 IU/L, alanine transaminase concentration of 114 IU/L, lactic dehydrogenase concentration of 1105 IU/L, total bilirubin of 2.0 mg/dL, C-reactive protein concentration of 7.22 mg/dL, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) of 166.8 ng/mL, and CA 19–9 of 157.9 U/mL. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed multiple liver tumors (Fig. 1a–c), including a tumor that perforated the sigmoid colon cancer with surrounding free air (Fig. 1d). Diagnosis was acute pan-peritonitis due to sigmoid colon cancer perforation with metastatic liver tumors and emergency surgery was performed.

Operative findings

A median incision was made and dirty ascites, including fecal contamination, significant bowel edema, and multiple liver tumors, were noted. We located the perforating sigmoid colon tumor (Fig. 2a) and performed Hartmann’s operation. The sigmoid colon cancer perforation was noted in the resection specimen (Fig. 3). However, at the end of the operation, we were not able to close the wound due to gut edema and concern of abdominal compartment syndrome. Thus, the abdominal wound was left open and we performed NPWT (Fig. 2b–d). Following the operation, the patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (ICU). Histopathological diagnosis was adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon.

Colectomy specimen. Gross examination of the specimen revealed a large central tumor and a small perforated hole (dotted circle) adjacent to the tumor. Histopathology identified moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon (S, Type 2, 50 × 40 (mm), pT4b, int, INF-β, ly1, v2 (EMG), PN1b, pNx, pPM0 (15 mm), pDM0 (40 mm), RM1), categorized as stage IV, according to both the Japanese and TNM classifications

Postoperative course

Two days after the primary emergency operation, a secondary operation was performed to determine whether the wound could now be closed. We concluded that it was still not possible to close the wound and performed continuous NPWT with mesh fascial traction (Figs. 4 and 5).

Findings at the second operation. The gut was edematous and the wound could not be closed. Thus, mesh traction was performed. a The gut edema did not improve at all. b, c Medical form padding (intraperitoneal) was introduced and mesh fascial traction was performed. d We covered the mesh traction with medical form padding (outside)

Five days after the primary operation, a third operation was performed. However, the wound still could not be closed. Thus, the abdominal space was irrigated, and three drains were inserted at the Douglas, Winslow, and left subphrenic spaces.

A fourth operation was performed at 7 days and revealed improvement in the bowel edema. However, edema of the abdominal wall persisted. Thus, we irrigated the abdominal space and continued NPWT with mesh fascial traction (Fig. 6).

Nine days after the primary operation, a fifth operation was performed and revealed significant improvement in the bowel and abdominal wall edema. We were then able to close the wound without any complications (Fig. 7). The patient was weaned from mechanical ventilation and extubated 15 days after the primary operation. However, the growth of the multiple liver metastases could not be inhibited and jaundice did not improve. The patient died of the disease 18 days after the primary operation.

Discussion

Common conditions that require open abdomen management include abdominal trauma, abdominal aortic surgery, and severe peritonitis [9, 10]. As peritonitis is often encountered in emergency surgery and the wounds sometimes cannot be closed in severe cases, surgeons must be familiar with some form of open abdominal management [11].

In this case, we performed NPWT with fascial mesh traction in a patient whose wound could not be closed following emergency peritonitis surgery. The wound was ultimately closed 9 days postoperatively without any complications, after a total of five operations. In many cases, the NPWT method requires film dressings to be changed every 2 to 3 days. Therefore, patients undergoing NPWT generally require frequent operative procedures. We also performed postoperative management in the ICU.

The effectiveness of mesh traction in this case is noteworthy. The reason for the difficulty of wound closure was intestinal edema as well as retraction of the rectal muscle laterally with time. Thus, it is important to maintain continuous muscle tension during treatment.

In the performed procedure, we excised the central portion of the mesh and sutured it back together to provide effective traction in each operation and subsequent narrowing of the defect (Figs. 4, 5B, and 6) [4]. This method does not require exchange of the mesh in each operation and makes it easy to adjust the tension of the mesh traction in a short time. Moreover, this method did not require any special materials and was easy to perform, even for surgeons who do not specialize in emergency surgery. In the fourth operation, the gut edema had significantly decreased. At that time, mesh fascial traction prevented the muscle from retracting laterally. Therefore, we were able to prepare for wound closure. Finally, in the fifth operation, we were able to close the wound.

NPWT is a highly effective method of wound closure with much better results than temporary closure [7, 12]. Furthermore, treatment outcomes (wound closure) have been shown to improve dramatically by adding mesh traction [6, 8, 13,14,15,16].

The current case demonstrated that NPWT plus mesh traction is the simplest and most effective treatment method currently available. Initial surgery is often finished with only NPWT. In cases where wound closure is judged to be difficult within a short time, adding mesh traction would increase the success rate. If the patient’s condition or intestinal edema is severe and long-term open abdominal management is likely to be needed, mesh fascial traction could be introduced in the initial surgery.

The current case involved a highly metastatic liver cancer, and the patient did not survive; however, if the cancer was not so advanced, the patient could have survived using this method.

Conclusions

Gastroenterological surgeons must learn some form of open abdominal management for severe peritonitis. This case suggests that NPWT with mesh fascial traction is effective for wound closure in patients with severe peritonitis. Furthermore, this method did not require any special materials, was easy to perform, and may provide better open abdominal closure than any other technique currently available.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- NPWT:

-

Negative pressure wound therapy

- POD:

-

Postoperative day

References

Stevens P. Vacuum-assisted closure of laparostomy wounds: a critical review of the literature. Int Wound J. 2009;6(4):259–66.

Labler L, Zwingmann J, Mayer D, Stocker R, Trentz O, Keel M. V.A.C.® Abdominal Dressing System. Eur J Trauma. 2005;31(5):488–94.

Quyn AJ, Johnston C, Hall D, Chambers A, Arapova N, Ogston S, et al. The open abdomen and temporary abdominal closure systems—historical evolution and systematic review. Color Dis. 2012;14(8):e429–38.

Lord AC, Hompes R, Venkatasubramaniam A, Arnold S. Successful management of abdominal wound dehiscence using a vacuum assisted closure system combined with mesh-mediated medial traction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97(1):e3–5.

Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Biffl W, Leppaniemi A, Henry S, Scalea TM, et al. International consensus conference on open abdomen in trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(1):173–83.

Atema JJ, Gans SL, Boermeester MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the open abdomen and temporary abdominal closure techniques in non-trauma patients. World J Surg. 2015;39(4):912–25.

Acosta S, Bjarnason T, Petersson U, Palsson B, Wanhainen A, Svensson M, et al. Multicentre prospective study of fascial closure rate after open abdomen with vacuum and mesh-mediated fascial traction. Br J Surg. 2011;98(5):735–43.

Rasilainen SK, Mentula PJ, Leppaniemi AK. Vacuum and mesh-mediated fascial traction for primary closure of the open abdomen in critically ill surgical patients. Br J Surg. 2012;99(12):1725–32.

Seternes A, Myhre HO, Dahl T. Early results after treatment of open abdomen after aortic surgery with mesh traction and vacuum-assisted wound closure. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40(1):60–4.

Sorelius K, Wanhainen A, Acosta S, Svensson M, Djavani-Gidlund K, Bjorck M. Open abdomen treatment after aortic aneurysm repair with vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45(6):588–94.

Perathoner A, Klaus A, Muhlmann G, Oberwalder M, Margreiter R, Kafka-Ritsch R. Damage control with abdominal vacuum therapy (VAC) to manage perforated diverticulitis with advanced generalized peritonitis—a proof of concept. Int J Color Dis. 2010;25(6):767–74.

Roberts DJ, Zygun DA, Grendar J, Ball CG, Robertson HL, Ouellet JF, et al. Negative-pressure wound therapy for critically ill adults with open abdominal wounds: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):629–39.

Willms A, Schaaf S, Schwab R, Richardsen I, Bieler D, Wagner B, et al. Abdominal wall integrity after open abdomen: long-term results of vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction (VAWCM). Hernia. 2016;20(6):849–58.

Acosta S, Bjorck M, Petersson U. Vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction for open abdomen therapy—a systematic review. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2017;49(2):139–45.

Tolonen M, Mentula P, Sallinen V, Rasilainen S, Backlund M, Leppaniemi A. Open abdomen with vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction in patients with complicated diffuse secondary peritonitis: a single-center 8-year experience. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(6):1100–5.

Willms A, Schaaf S, Schwab R, Richardsen I, Janig C, Bieler D, et al. Intensive care and health outcomes of open abdominal treatment: long-term results of vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction (VAWCM). Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2017;402(3):481–92.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Enago (https://www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK drafted the manuscript and performed the surgery. JH and SK participated in the surgery. JH, SK, and EU revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s wife for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kogo, H., Hagiwara, J., Kin, S. et al. Successful abdominal wound closure for treatment of severe peritonitis using negative pressure wound therapy with continuous mesh fascial traction: a case report. surg case rep 4, 46 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-018-0453-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-018-0453-0