Abstract

Introduction

Vertical transmission of covid-19 is possible; its risk factors are worth researching. The placental changes found in pregnant women have a definite impact on the foetus.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 25-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 2 (2 alive children), with a history of two caesarean deliveries, who was infected by the SARS-CoV-2 during the last term of her pregnancy. She gave birth by caesarean at 34 weeks of gestation to a newborn baby also infected with SARS-CoV-2. The peri-operative observations noted several eruptive lesions in the pelvis, bleeding on contact. Microscopic examination of the foetal appendages revealed thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta and in the umbilical cord vessels.

Conclusion

This case is one of the first documented cases of COVID-19 in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa. We strongly suggest obstetricians to carefully examine the aspect of the peritoneum, viscera and foetal appendages in affected pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In December 2019, first cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) due to a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) were reported from Wuhan in China. Soon after, the disease, subsequently named “the 2019 novel coronavirus disease” (COVID-19) and declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [1], has resulted in over 18.9 million confirmed cases and more than 709,000 deaths worldwide [2].

The pregnant woman can be considered to be more at risk of severe form than the non pregnant woman [3]. Their fragile immunity and frequent comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, or cardiovascular diseases may expose them at higher risks of developing severe forms of the disease [4] and to adverse pregnancy outcomes, especially during the third trimester [5]. COVID-19 causes pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which can compromise natural delivery, increase maternal morbidity, or even lead to maternal death [6]. Knowledge about coronavirus disease during pregnancy is still limited [4], and vertical transmission in utero is not yet well established [4, 5].

The risk of mother-to-child transmission of COVID-19 seems to be low [7,8,9]. Cases of perinatal transmission of COVID-19 have been described, but it is still unclear if this occurred via the transplacental or other routes during delivery [10]. Furthermore, COVID-19 may constitute a threat of premature delivery, intrauterine growth retardation, premature rupture of the membranes, in-utero foetal death or even a premature neonatal death during delivery or soon after [8]. Among pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2, preterm birth is reported 12.9% [11].

There are no established guidelines about the best timing nor the best mode of delivery in COVID-19 infected pregnant women to optimize foetal and maternal well-being [12]. A study on the association between mode of delivery and maternal and neonatal outcomes in COVID-19 patients in Spain has shown that caesarean section was associated with an increased risk for maternal clinical deterioration which remained significant after adjustment for confounders [13]. However, a few case-reports have shown a benefit of a caesarean section on the improvement of respiratory distress in severely affected patients [5, 12]. There have been only a few studies that have investigated the intraoperative findings in women undergoing caesarean delivery [14], or changes in the foetal appendages that may explain the risk of maternal-foetal transmission [15].

We report the first documented case of COVID-19 in a pregnant woman recorded in the province of South Kivu, in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) who gave birth by cesarean section to a premature newborn also infected by SARS-CoV-2. Her pelvic organs exhibited a particular inflammatory appearance, and fetal appendages revealed thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta and in the umbilical cord vessels.

Case presentation

A 25-year-old woman, gravida 3 para 2, at 34 weeks of gestation, with no medical history of cardiovascular nor other chronic diseases, was admitted to the labour and delivery unit of the “Hôpital Provincial Général de Référence de Bukavu” (HPGRB), in South-Kivu, for preterm labour contractions in a context of COVID-19. She had an history of 2 previous caesarean sections (the first one due to a cervical dystocia and the second indicated because of the prior caesarean), her last born wasaged 16 months. Her husband, tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, was a contact person of a COVID-19 confirmed case.

Three weeks before admission, she complained of fever, not responding to acetaminophen. Her obstetrician prescribed her antibiotics, anti-malaria, and anti-spasmodic drugs. Two weeks later, as fever persisted despite all these medications, a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) nasopharyngeal swabs was performed and confirmed she was infected by SARS-CoV-2.

She was then admitted to the provincial COVID-19 treatment center for isolation and health care. Upon arrival to the center, her body temperature was 38.7 °C. Gynecologic examination was unremarkable. All bacteriological tests, including hemocultures and cultures of urines were negative. She received antipyretics (acetaminophen), antispasmodics trimethylphloroglucinol and antibiotics (oral azithromycin for 5 days and intravenous ceftriaxone). Two days later, she complained of hypogastric pain, like uterine contractions of low intensity. Obstetricians of the HPGRB were contacted and recommended the administration of antispasmodics intravenously in perfusion. Despite this treatments, fever and uterine contractions persisted, so intravenous dexamethasone 12 mg daily was administered for fetal pulmonary maturation, associated with a tocolysis using nifedipine for 48 h. As the frequency, intensity and duration of contractions increased, accompanied by cervical changes (dilation, effacement, softening, and movement to a more anterior position), the patient was transferred to the labour and delivery unit of the HPGRB for an optimal care. A rapid SARS-Cov-2 antigen test was performed and found to be negative.

On admission at the HPGRB, the patient had a good general condition. Her temperature (36.5 °C) and blood pressure (120/60 mmHg) were normal. The uterine height was 29 cm, the fœtus was in cephalic presentation. On vaginal examination, the uterine cervix was softened, median, 5 mm long and had a 5 cm dilatation. Membranes were intact and the fœtal head was mobile. An obstetrical ultrasound confirmed the cephalic presentation and estimated the foetal weight at 1600 g. Foetal monitoring confirmed a foetal well-being, with a stable foetal cardiac rhythm around 140 beats per minute. Tocography showed two to three contractions per minute and an intensity of 50 to 60 mmHg. A diagnosis of intractable preterm labor in a COVID-19 patient with a history of iterative caesarean deliveries was made.

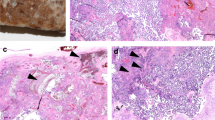

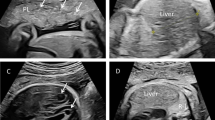

A classic Caesarean section with a Pfannestiel incision was performed. The peritoneal cavity and uterus were found to be very inflamed. Fetal appendages as well as the bladder were strewn with eruptive, vesicular lesions bleeding on contact (Figs. 1 and 2). The amniotic fluid was opalescent. The placenta weighed 500 g and had a clot on the maternal side on less than 20% of the surface. Anatomopathological examination subsequently revealed thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta and in the umbilical cord vessels (Figs. 3 and 4), and a diffuse hyalinization with marked angiogenesis of the villous stroma.

About five minutes after skin incision, a female newborn weighing 1760 g was delivered with 1 and 5 min APGAR scores of 9–10. The newborn was immediately transferred to the neonatal ward for specialized neonatal treatment for an optimal care and to minimise the potential risk of infection. Gestational age was estimated at 33 weeks according to the Finnstrom score. The newborn received the usual care (drying, stimulation, vitamin K1,

Fluorescein and care of the umbilical cord). A gastric liquid was collected by gastric tube, and different swabs (especially nasopharyngeal, ear and umbilical cord), as well as blood cultures were immediately performed for bacteriological investigations and for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test.

The newborn was breathing autonomously, had a good control of body temperature and blood sugar. She received a 10% glucose infusion for 48 h, and on the second day an enteral feeding by nasogastric tube was progressively introduced, using artificial milk formulas adapted to preterm babies. Prophylactic antibiotherapy (penicillin G and amikacin) was initiated, considering the risk of neonatal infections in prematurity.

On postnatal day 3, the newborn baby presented jaundice, respiratory distress and a clinical picture of ulcerative enterocolitis. Hemocultures were found negative, but SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was positive in oropharyngeal swab and cultures of gastric liquid isolated multiresistant Citrobacter sp. and Enterobacter cloacae. A phototherapy was prescribed for 3 days and previous antibiotics were replaced by meropenem and vancomycin based on the antibiogram. Despite this treatment, the newborn died on Day 5 in a picture of severe neonatal sepsis.

The postoperative follow-up of the mother was marked by a persistence of fever for 3 days, varying between 39 and 40 °C. Although haemocultures and urine cultures were sterile, antibiotic therapy was readjusted on postoperative Day 3 as for the newborn, with ceftriaxone replaced by meropenem. C-reactive protein (CRP) varied from 106.53 mg/l on admission to 186 mg/l on postoperative Day 1, falling to 21.93 mg/l on Day 5 and below 3 mg/l on Day 7. After 7 days of hospitalization, the patient’s condition was stable, with no fever nor respiratory symptoms. She was discharged from the hospital and sent back to the COVID-19 isolation Center. A control of the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was negative on Day 13, she returned back home. The late postpartum up to 6 weeks was unremarkable, with no complication.

No medical staff involved in this case was subsequently found to be infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Discussion

One year after the first cases of COVID-19, the disease continues spreading at striking speed in many countries worldwide. People get contaminated mainly through direct means (including respiratory droplets and physical contacts with carriers) or by indirect contacts with contaminated objects [16]. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy is another possible route of transmission [9], although further investigations are still needed to confirm this eventuality.

In previously published case reports of neonatal SARS-CoV-2 infections, it was not well established if the contamination occurred during pregnancy or after birth, especially during the delivery process [17].

Peritoneal lesions associated with SARS CoV-2 were previously suspected in patients [18,19,20]. Recently, the transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was reported [21, 22] and a classification of the COVID-19 infection in pregnant women, foetuses and newborns was suggested [23].

This case-report highlights a number of facts which suggest a possible intrauterine transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. We recognize, however, the limitations of our means of exploration which would confirm the case. Furthermore, none of the medical staff involved was subsequently found to be infected by SARS-CoV-2.

The intense inflammatory reaction of the uterus and foetal appendages suggest a direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 on placenta.

Conclusion

This case is one of the first documented cases of COVID-19 in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa. The intense inflammatory reaction of the uterus and foetal appendages suggest a direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 on placenta.

We strongly suggest obstetricians to carefully examine the aspect of the peritoneum, viscera and foetal appendages in affected pregnant women.

Availability of data and materials

Materials and data provided in this case study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo

- HPGRB:

-

Hôpital Provincial Général de Référence de Bukavu,

References

OMS. COVID-19 – Chronologie de l’action de l’OMS [Internet]. OMS. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19

World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation report 200. 2020.

Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, Galang RR, et al. Update: characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status — United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(44):1641–7.

Ellington S, Strid P, Tong VT, Woodworth K, Galang RR, Zambrano LD, et al. Characteristics of women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by pregnancy status - United States, January 22-June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Jun;69(25):769–75.

Kolkova Z, Bjurström MF, Länsberg J, Svedas E, Andrada M, Hansson SR, et al. Obstetric and intensive-care strategies in a high-risk pregnancy with critical respiratory failure due to COVID-19 : A case report. Case Reports Womens Health. 2020;27:0–4.

Goodnight WH, Soper DE. Pneumonia in pregnancy. Vol. 33, Critical Care Medicine; 2005.

Schwartz DA. An analysis of 38 pregnant women with COVID-19, their newborn infants, and maternal-fetal transmission of SARS-CoV-2: maternal coronavirus infections and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020.

Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from coronavirus 2019-NCOV (SARS-CoV-2) infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses. 2020;12(2):1–16.

Karimi-Zarchi M, Neamatzadeh H, Dastgheib SA, Abbasi H, Mirjalili SR, Behforouz A, et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) from infected pregnant mothers to neonates: a review. Fetal Pediatr Pathol [internet]. 2020;0(0):1–5 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/15513815.2020.1747120.

Richtmann R, Torloni MR, Oyamada Otani AR, Levi JE, Crema Tobara M, de Almeida SC, et al. Fetal deaths in pregnancies with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Brazil: a case series. Case Reports Womens Health. 2020;27:e00243.

Woodworth KR, Olsen EO, Neelam V, Lewis EL, et al. Birth and infant outcomes following laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy — SET-NET, 16 jurisdictions, march 29–October 14, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(44):1635–40.

Oliva M, Hsu K, Alsamarai S, De Chavez V, Ferrara L. Clinical improvement of severe COVID-19 pneumonia in a pregnant patient after caesarean delivery; 2020.

Martínez-Perez O, Vouga M, Cruz Melguizo S, Forcen Acebal L, Panchaud A, Muñoz-Chápuli M, et al. Association between Mode of Delivery among Pregnant Women with COVID-19 and Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes in Spain. JAMA. 2020;324:296–9.

Ngaserin SHN, Koh FH, Ong BC, Chew MH. COVID-19 not detected in peritoneal fluid: a case of laparoscopic appendicectomy for acute appendicitis in a COVID-19-infected patient. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2020;9:1–3.

Ng WF, Wong SF, Lam A, Mak YF, Yao H, Lee KC, et al. The placentas of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a pathophysiological evaluation. Pathology. 2006;38(3):210–8.

Lot M, Hamblin MR, Rezaei N. COVID-19: Transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. 2020;(January).

Lu Q, Shi Y. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and neonate: What neonatologist need to know. J Med Virol. 2020;92:564–7.

Ahmed AOE, Mohamed SFH, Saleh AO, Al-Shokri SD, Ahmed K, Mohamed MFH. Acute abdomen -like-presentation associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases [internet]. 2020;21:e00895 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00895.

Blanco-Colino R, Vilallonga R, Martı’n R, AM PC. Suspected acute abdomen as an Extrapulmonary manifestation of Covid-19 infection. Cir Esp. 2020;98(5):295–305.

Cabrero-Hernández M, García-Salido A, Leoz-Gordillo I, Alonso-Cadenas JA, Gochi-Valdovinos A, González Brabin A, et al. Severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with suspected acute abdomen: a case series from a tertiary hospital in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(8):E195–8.

Vivanti AJ, Vauloup-Fellous C, Prevot S, Zupan V, Suffee C, Do Cao J, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2020;11(1):1–7 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17436-6.

Sisman J, Jaleel MA. Intrauterine transmission of SARS-COV-2 infection in a preterm infant. PIDJ. 2020;39(9):265–7.

Shah PS, Diambomba Y, Acharya G, Morris SK, Bitnun A. Classification system and case definition for SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(5):565–8.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all those persons who contributed to this work, especially Dr. BULAMBO ASOKA Blandine.

Authors sincerely thank all the staff of Provincial referral Hospital of Bukavu for their collaboration for this case study.

Funding

This case report received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EKB: drafted the manuscript, reviewed the literature, followed up the patient and edited the final manuscript. GMM, SZM, PMK, EBM, DGM, MB and GBB edited and revised the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The publication of this case was approved by the Ethics committee of the Catholic University of Bukavu, DRC.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication of the clinical details and/or laboratory results was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Birindwa, E.K., Mulumeoderhwa, G.M., Nyakio, O. et al. A case study of the first pregnant woman with COVID-19 in Bukavu, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. matern health, neonatol and perinatol 7, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-021-00127-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-021-00127-5

) with the posterior surface of the uterus, on the ovaries, the left fallopian tube up to Douglas’ pouch

) with the posterior surface of the uterus, on the ovaries, the left fallopian tube up to Douglas’ pouch

)

)

) in the form of congestion and thrombosis visualized in certain fields and large areas of stromal hyalinization

) in the form of congestion and thrombosis visualized in certain fields and large areas of stromal hyalinization

) in the lumen of the umbilical vessel, Wharton’s jelly is without distinction, no inflammatory reaction

) in the lumen of the umbilical vessel, Wharton’s jelly is without distinction, no inflammatory reaction