Abstract

Management practices are one of the most important factors affecting forest structure and function. Landowners in southern United States manage forests using appropriately sized areas, to meet management objectives that include economic return, sustainability, and esthetic enjoyment. Road networks spatially designate the socio-environmental elements for the forests, which represented and aggregated as forest management units. Road networks are widely used for managing forests by setting logging roads and firebreaks. We propose that common types of forest management are practiced in road-delineated units that can be determined by remote sensing satellite imagery coupled with crowd-sourced road network datasets. Satellite sensors do not always capture road-caused canopy openings, so it is difficult to delineate ecologically relevant units based only on satellite data. By integrating citizen-based road networks with the National Land Cover Database, we mapped road-delineated management units across the regional landscape and analyzed the size frequency distribution of management units. We found the road-delineated units smaller than 0.5 ha comprised 64% of the number of units, but only 0.98% of the total forest area. We also applied a statistical similarity test (Warren’s Index) to access the equivalency of road-delineated units with forest disturbances by simulating a serious of neutral landscapes. The outputs showed that the whole southeastern U.S. has the probability of road-delineated unit of 0.44 and production forests overlapped significantly with disturbance areas with an average probability of 0.50.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Southeastern United States (SEUS) forest comprises 32% of the total U.S. forestland (Oswalt et al. 2014), which combined with the productivity of the forest, places this region at the forefront of American forestry production (Fox et al. 2007). This heterogeneous landscape is composed of heavily managed forests, intensive agriculture, and multiple metropolitan areas. SEUS, although one of the most densely forested regions in the United States (Hanson 2010), is also heavily dissected by road networks (Coffin 2007). The diverse forest management patterns, reflecting long-term land-use legacies (Josephson 1989; Haynes 2002), contribute to the complex land mosaic of SEUS.

It is challenging to quantify the ecological and anthropogenic mechanisms that control the spatial structure of the forest landscape and its surrounding areas in these complex forest mosaics. Forest management is the predominant factor in forest ecology and structural patterns (Becknell et al. 2015), but little is known about how management practices are related to surrounding land-use at the regional scale. One thing that is known is that, in the SEUS, significant expansions of urban areas tend to convert forested land to urban uses and that croplands tend to transition to pine plantations (Davis et al. 2006; Haynes 2002; Wear and Greis 2002, 2012, 2013; Stanturf et al. 2003; Becknell et al. 2015). To understand the ecological and anthropogenic influences of differently managed forests on ecosystem processes, all landscapes should be understood at multiple scales, from the local scale (forest management unit) to regional scales, with the regional scale referring to broad forest mosaics that are formed from management patches (O’Neill et al. 1996). Understanding forest management spatial patterns require defining a map-based management unit, which is the subdivision regarding effects of land use on forest ecosystems. This research seeks to further the understanding of how spatial patterns of forest management affect land use, by posing the following questions: Do roads delineate forest management units? What is the spatial distribution of road-defined forest management units in the SEUS? Moreover, how are the distributions of management units affected by different forest management approaches? And how does forest management affect nearby land use, and how does nearby land use affect forest management?

Forest management is the main driving force of forest structure in SEUS (Becknell et al. 2015) and alters forest properties and processes, which affects forest ecosystem services (Kurz et al. 2008; Stephens et al. 2012; Oswalt et al. 2014). Forest management can be classified into four categories: production forestry, ecological forestry, passive management and preservation management (Becknell et al. 2015). Production management harvests forest products and sustains the bio-productivity of the system with the sole objective of producing wood, pulp, and other forest products. In SEUS, production management based on silviculture systems, which homogenize parts of the landscape, has predominated the SEUS (Siry 2002). However, forest conservation systems have evolved considerably over recent decades (Mitchener and Parker 2005; Franklin et al. 2007). Ecological management uses legacies of disturbance, including intermediate stand disturbance processes such as variable density thinning and fire, and variable and appropriate recovery times to manage forests that still produce economically valuable wood products while preserving many of the values of natural forests (Franklin et al. 2007). Passive management is defined as a practice with little or no active management. We argue that all forests are managed to some degree and that doing nothing is a form of management. Preservation forestry aims to minimize the ecological footprint of society with the objectives of protecting wildlife and maintaining ecosystem services. Furthermore, certain forest management practices can suppress wildfires (Waldrop et al. 1992), prevent insect /pathogen outbreaks (Netherer and Nopp-Mayr 2005; Faccoli and Bernardinelli 2014), change water yield and hydrologic regulation (Douglass 1983), produce wood products, provide places for hunting and recreation, and conserve habitat biodiversity.

Forestland structures, functions, and ecological processes are scale-dependent (Battaglia and Sands 1998; Niemelä 1999; Drever et al. 2006). Regionally, for the purpose of sustainable forest management, we need to develop criteria and indicators of management units. Forest management units in this study are zones or patches, which can be identified, mapped and managed according to the land-use objectives. Road networks link human activities (e.g. management practices) and surrounding physical environments (land cover). For production, preservation, and ecological forestry, in many cases, forest management units are harvest or burn units. Roads are built to create access for the managers and harvesters. For example, the preserved forest in the Ordway Swisher Biological Station (OSBS) in northcentral Florida is subdivided by road networks into management (burn) units, which is the smallest unit of land that is actively managed (Ordway-Swisher Biological Station 2015). In the Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center in Ichauway, Georgia, and OSBS, the internal road network provides access to the research site and serves as prescribed fire breaks (Ordway-Swisher Biological Station 2015). For passive management practices, there are currently no clear criteria defining the management units. However, in national forest systems (mostly with ecologically managed forests and multi-use production forests), existing roads and trails are used for controlling prescribed fire and wildfires (e.g. Apalachicola National Forest, Osceola National Forest, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service 1999). For an example of a privately-owned forest, the Red Hills region in Georgia uses roads to delineate burn units ranging approximately from five to 30 ha (Robertson and Ostertag 2007).

Road networks facilitate movements of humans and connect natural resources with societies and economies. As conduits for human access to nature, the physical footprint of approximately 6.6 million km of roads in the United States FHWA (Federal Highway Administration 2013) has significant primary and secondary impacts on ecosystems and the distribution of species (Bennett 1991). Fifteen to 20 % of American land is subject to the ecological effects of road networks (Forman and Alexander 1998; Forman and Deblinger 2000). The most noticeable effects of road networks on forest structures are landscape structure changes, including reduced mean patch size, increased patch shape complexity, increased edge densities, and reduced unit connectivity. In one case, McGarigal et al. (2001) investigated the landscape structure changes of the San Juan Mountains from 1950 to 1993 and found that roads had a more significant ecological impact (e.g. core forest areas and patch sizes decrease) on landscape structure than logging activities.

In addition to management practices (e.g., harvesting, fertilizing), the construction of road networks divides the forested land into smaller patches, thereby increasing the potential intensity of the effects of management practices. Road networks in managed forests provide easy access for managers and harvesters to extract and regenerate resources (Demir and Hasdemir 2005). Roads may influence fire regimes by increasing fire ignition as a result of human activities (Franklin and Forman 1987). Moreover, road networks alter the spatial configuration of management patches by functioning as firebreaks, which form new patterns in landscapes (Franklin and Forman 1987; Nelson and Finn 1991; Eker and Coban 2010). By quantifying the spatial patterns of management units created by roads we may gain insight into the ecological effects of road networks on spatial forest structures within differently managed areas.

The impacts and ecological effects of roads on the landscape might be misestimated because methods measuring the road-effect zones and landscape scale effects are not yet well developed (Ries et al. 2004; Hou et al. 2013). Roads and streams may be challenging to identify, or invisible because they do not open the canopy so that many roads are not detectable on satellite imagery or even aerial photography. The reliability of large-scale road data is also challenged due to issues of accuracy, coverage and immediacy, all of which can underestimate the extent and ecological impacts of roads on forest structures (Riitters et al. 2004). We propose that common types of forest management are practiced in road-delineated units that are detectable by remote sensing satellite images coupled with crowd-sourced road network datasets. We also describe and study the patterns of forest management units in response to land ownership and different management practices.

Study area

We focus on the Southeastern U.S. Coastal Plain and Piedmont (SEUS) region (Fig. 1). The SEUS is located between Piedmont to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the east and covers a significant portion of the southeastern United States. The SEUS is the home to the most densely production-forested region nationwide, which makes up 32% of total U. S forest cover (Oswalt et al. 2014). Based on EPA eco-region descriptions, land cover in the SEUS is a mosaic of cropland, pasture, woodland and forests (Bailey 2004). Major silvicultural forests in SEUS are pine forests, such as slash pine (Pinus elliottii Engelm.) and loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) forests. European settlement and the extensive harvesting in the early 1900s removed 98% of the original longleaf pine (Pinus palustris Mill.) forests, which was one of the most dominant ecosystems in SEUS (Outcalt 2000) and converted them to plantations of native slash pine. The SEUS forest system is a fire-dominated system with native trees adapted to short-period stand-clearing events. The primary forest management types are production and passive management due to the dominant ownership of private owners, logging companies, and investment institutions (Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and Timber Investment Management Organizations (TIMOs)) (Zhang et al. 2012). This diversity of land cover types is spatially heterogenous, and patch sizes of the numerous vegetation classes vary across a wide range of scales (Fig. 1).

Study area of Southeastern United States Coastal Plain and Piedmont, with level III ecoregions (Bailey 2004)

Data sources

Forest extent

In this study, forest extent is determined by a composite of the 2006 and 2011 USGS National Land Cover Database (NLCD), which was constructed from Landsat imagery at 30-m spatial resolution (Jin et al. 2013). We aggregated 21 NLCD classes into two classes: forest (deciduous, evergreen, mixed forest and woody wetland) and non-forest (including water). Only the pixels that contain 50% or more forest area in NLCD will be considered as forested pixels. We also extracted the SEUS urban areas by using the most recent 2015 US Census Bureau’s TIGER cartographic boundary urban areas (TIGER 2015) dataset to remove urban areas from the analysis.

Forest management type

An integrated random forest classifier was built from the analysis of long-term phenological features derived from BFAST outputs and spectral entropy calculated from the Terra-MODIS enhanced vegetation index (EVI: MOD13Q data product), along with ancillary data such as land ownership, and disturbance history to classify different forest management types (Breiman 2001; Verbesselt et al. 2010; Zaccarelli et al. 2013). The forest management type map has a spatial grain of 250 m and is a composite of phenological patterns and changes in the patterns from February 2001 through December 2016 (Figure S1). The SEUS forest management type map has an overall accuracy of 89% for a 10-fold cross-validation. The forest management raster is available for each region as georeferenced GeoTIFF rasters with a 250-m resolution from PANGAEA (Marsik et al. 2017).

Road networks

We selected OpenStreetMap as the primary road data and the USDA National Forest service trail and road maps (https://data.fs.usda.gov/geodata/edw/datasets.php?dsetCategory=transportation, accessed Dec 2016) as secondary in this study. OpenStreetMap is a collaborative, crowdsourced project that creates free, open, and accessible maps of road networks. OpenStreetMap is one of the most popular and well-supported Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) datasets (Mooney et al. 2010). Community volunteers collect geographic information and submit it to the global OpenStreetMap database (Ciepluch et al. 2009). OpenStreetMap monitors road networks at near real-time and includes additional classes of roads such as private access roads and driveways in rural areas, small service roads or alleys in urban areas, and forest access roads. All those road features are critical for this research and no distinctions were drawn between the types of road, traffic volume, or other factors. OpenStreetMap shows up-to-date road networks information, which the other official road databases do not offer. The accuracy of the OpenStreetMap in our study region has been studied. For the state of Florida, Zielstra and Hochmair (2011) compared road networks dataset from different sources and concluded that OpenStreetMap was significantly better the other road databases. All OpenStreetMap data were downloaded from the website of Geofabrik (http://download.Geofabrik.de, Accessed Dec 2016). USDA National Forest Services Trails and Road Map provide the coverage of detailed transportation map in National Forests (Coghlan and Sowa 1997).

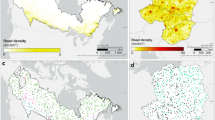

Road density in SEUS was measured as the total length of all roads (in kilometers) in a district divided by the total land coverage area of the district (km2) based on our developed road networks map (Figure S2).

Landscape fire and resource management planning tools (LANDFIRE)

Disturbance data from the Landscape Fire and Resource Management Planning Tools (LANDFIRE) disturbance database were used to evaluate the management unit map. LANDFIRE is a combination of Landsat images, fire program data, and cooperator-provided field data and other ancillary databases (e.g., PAD-US), and is a shared program between the wildland fire management programs of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Services and U.S. Department of the Interior (Rollins 2009). LANDFIRE also describes land cover/use both spatially and temporally from 1999 to 2014 and provides the existing vegetation composition map based on dominant species or group of dominant species. Spatially, LANDFIRE is a Landsat-based (30 m) database, which matches the 30-m spatial resolution of this study (https://www.landfire.gov/disturbance.php). We chose the LANDFIRE project data because the spatial scale is small enough to detect subtle changes brought about by land management practices, and large enough to reflect the characteristic variability of essential ecological processes (such as wildfire) in the appropriate spatial context. The disturbance data from LANDFIRE will be used to evaluate management units delineated by the road network in the context of intensely managed forests in SEUS (Figure S3).

Forest ownership

Geospatial land-ownership data from federal and nongovernmental agencies were integrated for land ownership mapping (Figure S4). Forest ownership in SEUS is broadly categorized as publicly owned and privately owned according to the landowners. There are six sub-types of public ownership, which are federally protected, federal, state protected, state, military, and local. Also, there are four sub-types of private ownership: non-governmental organization, private, family, and corporate. The ownership classification implies different management objectives, as well as landowner skills, budgets and interests. Datasets from other federal and state government agencies were regrouped and classified into ten sub-types to create a comprehensive dataset that includes public land ownership and privately protected easements as well as specially designated areas and associated protection level (see Table S1). The final product is a 250-m spatial resolution raster data depicting the forest ownership types and resampled to 30-m in this study to match the spatial resolution of the NLCD database.

Methods

Mapping road-delineated units

In each forest management type, the fundamental element of management practice is the management unit. In this study, we define the individual forest clusters that delineated by road-networks as “management units” and the clusters that directly derived from forest extent map as “management patches.” We hereby developed two comparative methods for landscape analysis by using two sets of input data, with and without incorporating OpenStreetMap. For the method without incorporating OpenStreetMap, management patches were mapped on the forest extent map resulting from the map described in the section of Forest Extent and the Region Group tool in ESRI ArcGIS 10.X (ESRI Inc.,) to identify clusters of forest pixels that formed unique and unconnected forests.

Road-delineated forests units were mapped on the forest extent map from the section of Forest Extent after superimposing detailed road networks with the Region Group tool to identify forest clusters as units. When superimposing road maps, all road networks were converted to one-pixel segments. After one-pixel wide road segments were derived, we converted all the forest pixels to 1 and the pixels that contained at least one road segment to non-forest pixels (30-m spatial resolution) to 0.

Geospatial assessment

In SEUS, regional forest management activities were represented as disturbances as described by LANDFIRE data, such as clear cuts, fires, and thinning. Figure 2 shows the example view of LANDFIRE cumulative disturbance with delineated forest extent, and it can be clearly observed (with the Warren’s Index of 0.62) that the disturbed areas and delineated unit shared boundaries and show a large degree of equivalence. The spatial coincidence has been shown to facilitate the interpretation and integration of defining regional forest management units. In this study, we propose a test based on forest management unit and the geographic corresponding forest disturbances to compare the geographical similarity between the management unit and corresponding forest disturbances. The assessment of geographic image overlap is analogous to quantifying the niche similarity of two species in two dimensions. As two-dimensional rasters, both disturbance and forest extent data can be treated as homogenous and spatial-explicit datasets.

Testing the overlap between pairs of road-delineated forest extent with disturbance regions was compared using the similarity statistics of Warren’s Index (Warren et al. 2008). The values of Warren’s Index range from 0 to 1. The value of 0 means forest management units have no spatial overlap with forest disturbance areas, and 1 means all forest management units are identical to disturbance areas. The statistics of Warren’s Index assume probability distribution defined over geographic space, in which the pX, i (or pY, i) denotes the spatial probability distribution of X (road-delineated forests compartments), or Y (probability distribution of forest disturbances) to cell i. In nature, Warren’s equivalency index carries no biological assumptions concerning the parameters as being from any probability distributions. Spatially, we applied it into assessing road-delineated forest management units versus the areas of corresponding disturbances.

Firstly, the Hellinger distance was calculated to measure and compare the probability distance (Van der Vaart 1998):

while the Warren’s statistic is:

To measure and quantify the similarity of differently managed management units with the corresponding disturbance areas, all the units were classified into four groups (ecological, passive, preservation and production management). A 10 km × 10 km grid was utilized to compute Warren’s Index over the SEUS. The inputs of this iterative Warren’s Index spatial analysis are: 1) stacked disturbance area data from LANDFIRE and 2) corresponding road-delineated forest management units. These analyses were carried out using the nivheOverlap function of dismo package in R 3.3.X (Hijmans et al. 2015).

We further tested the hypothesis of road delineated forest management units by generating neutral landscape models from two perspective as:

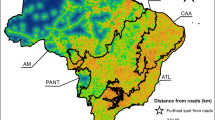

1) Spatially. In this study, we used the Worldwide Reference System 2 (WRS-2) row 17 path 39 (17_39 hereafter), which is one scene of Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM). As shown in Fig. 3, the forests in 17_39 are heavily disturbed and fragmented, but it also shared the larges contiguous forests in SEUS (Okefenokee National Refuge). This heterogeneous landscape consists of a mixture of natural and plantation forests, urban centers, urban and rural residential areas, and commercial and small-scale agricultural operations. Instead of using LANDFIRE disturbance data, we simulated a neutral disturbance layer by mimicking the disturbance patch shape and area called “Random NLM” (Saura and Martinez-Millán 2000; Sciaini et al. 2018). 17_39 was divided into 325 individual landscapes with the spatial resolution of 30 m (10 km × 10 km in size), which means each landscape in 17_39 contains 333 × 333 pixels (10,000 ha). We applied the neutral landscape generation algorithm in each landscape in 17_39 for 325 times and recalculated the Warren’s Index for each 10 km × 10 km landscape with the simulated disturbance layer with the road networks delineated forest extent map.

Case study region of Worldwide Reference System 2 (WRSII) row 17 path 39 (17_39). As the LANDFIRE EVT product shows, it encompasses a diversity of landcover and disturbance types. Much of the conifer and conifer-hardwood land cover found outside of the large riparian area of the Okefenokee Swamp (upper central) are heavily managed, privately owned plantations and mixed agriculture/timber land use

2) Iteratively. We applied a range-based attribute filter to the SEUS road density map (Figure S2). The road densities range from 0 to 91.48 km∙km− 2, so we used the interval of 5 to randomly select a serious spatial noncorrelated 10 km × 10 km grids with a total number of 19 landscapes in SEUS (Fig. 4). For each spot, we iteratively run the Random NLM algorithm for 500 times and calculated the Warren’s Index with overlaying the simulated disturbance resulted from NLM with the road networks delineated forest extent map.

Results

Spatial assessment

We calculated the Warren’s Index with overlaying the road networks delineated forest extent with LANDFIRE disturbance map on a 10 km × 10 km grid in SEUS (Fig. 5). The total number of 10 km × 10 km grids is 11,072. Figure 5 shows the probability distribution of road network delineating management unit, with an average of 0.44 and the standard deviation is 0.28. We also computed the distribution and found that most forested areas have the Warren’s Index from 0.3 to 0.5. When we extracted 17_39 (Fig. 6a), shown as Fig. 6b with the mean value of 0.54 and the standard deviation of 0.17.

The spatial distribution map of Warren’s Index overlaying the road network delineated forested extent with neutral simulated disturbance map over 17_39 area (a). (b) is the one of 10 km × 10 km simulated landscapes, (c) is the distribution of the warrens’ I with the average value of 0.14 and the standard deviation of 0.08. The sub-figure shows the randomly simulated patches in a plot of 10 km by 10 km

By replotting the spatial probability of road networks delineating management units in 17_39 (Fig. 6c), we recalculated the histogram of how the Warren’s Index distributed over 17_39 region after replacing the LANDFIRE data with simulated disturbance layer, as shown in Fig. 6d. The mean value of the probability distribution is 0.14 with the standard deviation of 0.082. The results show that human-derived forest disturbances can result in a non-random association with forest extent. By comparing with the LANDFIRE disturbance derived Warrans’ I map (Fig. 6a), road networks make a great contribution in identifying and shaping forest patterns in the case study area 17_39, wherein SEUS reflect the management practices on the ground, and so for the road-delineated forest compartments, we hereby call them forest management units.

Road density in SEUS ranges from 0 to 91 km∙km− 2. Table 1 lists the info of all 19 10 km × 10 km grids with a variation of road densities, the mean values of 500 simulated landscapes. We compared the original Warren’s Index of all 19 landscapes with the mean values calculated from simulated landscapes, and found all the simulated landscape show significant difference on each landscape with the original Warren’s Index. We also plot the histogram of the landscapes to see how the simulated neutral landscape distributed (Fig. 7). A linear relationship between the Warren’s Index overlaying simulated disturbances and roads with the Warren’s Index overlaying LANDFIRE disturbances with roads (Figure S5) with R2 of 0.4755. It shows the evidence that roads help to shape forest patterns by statistical test and approve the hypnosis that road delineates forest management patterns.

Distributions of 19 simulated landscapes of SEUS (Numbers are corresponding with Fig. 4)

Forest management unit map

A total area of 5.24 × 107 ha managed forest was measured in the SEUS from the forest extent map based on NLCD. When we compared the NLCD derived forest/non-forest maps between 2006 and 2011, a strong tendency of deforestation was found on our study area (1.7 × 106 ha). The total length of the roads in SEUS is 2.26 million km, which was calculated based on the number of rasterized road network multiply the spatial resolution (30 m). The road densities in SEUS range from zero to 49.29 km∙km− 2 (Figure S2). We mapped the forest management units at regional scales, and the spatial distribution of those management units represented the diversity and heterogeneity of road-delineated forests clusters.

As the unit size increases, the number of units decreases in an approximately logarithmic manner (Fig. 8). Overall, 177,400 units occupied the SEUS with the mean size of 29.5 ha. We found that 35.94% of the forest management units represent more than 99% of the whole forest and ranged in area from 0.5 to 172,886 ha (the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge). The remaining 64.06% of small forest compartments, which are smaller than 0.5 ha, covers only 0.98% of the forested area.

The SEUS forests is dominated by management unit size ranging from 100 to 10,000 ha. The forest management unit-size class map was reclassified based on the forest management unit sizes (Fig. 9). From Fig. 9, it can be clearly seen that riparian forests stand out as large, unbroken linear features (most of the orange colored units), which cover average unit sizes from 10,000 to 100,000 ha. A characteristic feature for the southeastern forest is that relatively small and large management units locate close to each other, surrounded with small-sized units (Figs. 9 and 10). Figure 10 shows five close-ups/examples from multiple locations and landscapes. In our study area, the largest management unit is an area of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge (Georgia and Florida) with the size of 172,886 ha (Figs. 9 and 10d), followed by the Atchafalaya River basin in Louisiana at 102,367 ha (Fig. 9 and 10c). Riparian forests are often undisturbed in SEUS without much road access because their soils are too wet for harvesting machinery and the trees are not as valuable. There is also a cluster of large forest management units (yellow: 1000–10,000 ha) along the Piedmont ecoregion, and the middle part of the southeastern plains. The Atchafalaya River basin in southern Louisiana is full of canals and river channels but no roads. There are many smaller units in Alabama and Mississippi and central Louisiana due to the relatively high road density in this region, so the landscape is broken up according to the road density map. Another example is Fig. 10e, Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, is the largest intact forest across southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina and was established for protecting and managing the swamp’s ecosystem (USFWS 2006).

To illustrate the contributions of road networks to our regional SEUS management unit map, a representative comparison set was done with and without incorporating road networks data. In Fig. 11, we overlay the histogram of the management unit (incorporating road networks) with the histogram of the management patches (without incorporating road networks. The red histogram shows the size-based frequency distribution of patches without incorporating road networks and the purple histogram illustrates the size frequency of forest management units. When refining the management units with road networks, there are 17 times more patches (management patches) compared with the map without incorporating road networks (management units).

Discussion

Management units under different management approaches

Road density (Figure S2) has been proposed as a broad index of roads’ ecological effects in a landscape (Forman and Alexander 1998). The magnitude of average road densities ranges from 0.63 to 2.2 km∙km− 2 in all managed forests in SEUS. Preservation forest holds the lowest average road density of 0.63 km∙km− 2, and the passively managed forest has the highest average road density of 2.2 km∙km− 2. Ecological forest and production forest have the average road density of 1.86 and 1.29 km∙km− 2, respectively. One reason is the building of forest service roads and private logging roads, which obviously increase the road density in production forestland. Road density is a predictor of forest management intensity (Wendland et al. 2011), and the indicator of human interactions with forests (Forman et al. 2003). We compared the size-frequency distributions of management units with a map of different kinds of management (production, ecological, preservation, and passive management) derived independently. Preservation and production management had the largest patches, with means of 109.6 and 82.6 ha, respectively. Ecological and passively managed units averaged about half as large as 73.8 and 73.0 ha, respectively (Table 2).

We incorporated Warren’s Index to assess quantitatively the geographic overlap between forest management units under different functional forest management types. For ecological management, the specific practice is designed to emulate the outcome of natural disturbance, which is to create an uneven-age stand structure to manage competition between and within multi-cohort stands. The distribution of ecological management units shows spatial heterogeneity with structurally complex stands. For passive management forest lands, as the passively managed forests mostly adopt many irregular shapes with blurred boundaries, and rupture of connectivity. For preservation management forest: mostly large government-managed land for multiple-purpose including watershed, wildlife, recreation and wilderness aspects. Accordingly, various practices may be applied to it such as harvest, cutting, retention cutting, thinning and prescribed fire. As shown in Table 3, Warren’s Index represents the overlap between forest management units under different management types with the corresponding forest disturbance area.

The 10 km × 10 km based spatial grid analysis of Warren’s Index is shown in Fig. 5 and Figure S6, S7, S8 and S9. Among all four forest management types, production forestry showed the highest probability of road-delineated management units with I = 0.50, and the passive managed forests showed the lowest probability of road-delineated management units I = 0.33. As the dominant forest: production forests, the average size of plantation management units tends to be large, have a uniform composition (Figure S9), are internally homogeneous and involve practice such as clearcutting and thinning. For preservation/wilderness, across the whole SEUS, the probability of road-delineated management unit is 0.44, with the standard deviation of 0.29, because the large areas of wildfires happened but with road network setting as firebreaks. Roads provide access and firebreaks, as the use of prescribed fires is widespread in SEUS and much of the prescribed fires are on private lands (Haines et al. 2001). In this study, we used a threshold of 50% of the similarity score although many useful criteria for establishing such thresholds have been proposed (Jimenez-Valverde and Lobo 2007). In the analysis of Table 3, the criteria were just used to show binary predictions of four differently managed forests.

Ownership representation of forest management unit

Forest management activities are important links between human and environmental factors, especially at regional scale. Forest ownership patterns also explain different types of land management practices and trajectories of land cover change (Turner et al. 1996). The aim of this part of the research is to link regional land ownership to management. We produced the SEUS ownership database (Figure S4; Table S1) by collecting the data from different sources, where the ownership was divided as Private and Public. Based on our understanding of the SEUS forest ownership, we reclassified the forest owner types into public and private with 10 sub-classes (Table 4): 1) Public: Federal protected, federal, state protected, state, military, local and NGO lands; and 2) Private: Private, family and corporate forests. Our ownership data indicate that 18.7% of the landowners are under public forest and 81.3% of private forest landowners, which covers 41.5% and 58.5% total forestland.

We can see that the type of land ownership affects units’ distribution (Table 4). The special characteristics of SEUS forest ownership patterns can result in strong contrasts in management unit distribution. The major ownership types in the region are family, corporate and state, which have different management objectives. In addition, as the road networks increased, the number of small-sized parcels also shows a substantial increase.

The mean forest management units under different ownerships range from 73.2 (privately owned forests) to 115.9 ha (state protected forests) with the standard deviation of 33.4 ha. By comparing with Table 2, we found that the average unit size of military land is 74.9 ha, which is the closest to the average management unit size of ecological forestry at 73.8 ha. The land with the ownership of state protected represents the largest average management unit at 115.9 ha.

Conclusions

Quantifying forest management units under different management approaches is a key step to ensure that appropriate management practices and policies are in place to maintain the array of forest ecosystem services. Regionally, forest harvesting operations are conducted within road-defined boundaries. Forest management practices in SEUS are specifically the activities primarily dictated by forest harvest and the needs of management for recreation and sustainability. Roads networks in SEUS are often used for setting firebreaks and timber harvest boundaries, so there should be a spatial coincidence between road-delineated management units and disturbance. In this study, we assessed the forest management from stands to regional scale, by incorporating road networks and multi-temporal disturbance remote sensing database.

A number of conclusions can be drawn from the analysis in this study.

-

1)

Road networks play a role in delineating forests from local to regional scale. By defining the individual forest clusters delineated by road networks as “forest management units” and the clusters that directly derived from forest extent map as “management patches”, we mapped the forest extent map of both “units” and “patches” and compared them with treating “patches” map as background. There were 17 times more “units” than “patches” over the whole SEUS. And we also summarized the size distribution road delineated units, with units smaller than 0.5 ha comprised 64% of the counts of units, these small units altogether covered only 0.98% of the total forest area.

-

2)

We quantitatively tested the probability distribution patterns by using Warren’s Index of road-delineated management units and the corresponding forest disturbances area. The average probability of road-delineated management units is 0.44, and we also visualized the probabilities by setting a 10 km × 10 km grid. In SEUS, the high equivalency between the road-delineated units and the corresponding areas were found at most production forests, and large-size preserved areas (e.g. Okefenokee National Wildlife Preserve and St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge).

-

3)

The combination of remote sensing data and OpenStreetMap constitutes a useful tool to monitor, characterize and quantify land cover and management unit distributions at macrosystems scale. By using the NLCD as the forest reference data and OpenStreetMap as road networks dataset, we produced the OpenStreetMap refined management unit pattern map and analyzed the spatial size distribution of forest patterns. In addition, by incorporating the OpenStreetMap, the roads are shown to play an important role in causing fragmentation of the remnant forestlands. The size frequency distribution tells us that all of the 64% of management units are small management units (< 0.5 ha) making up just 0.98% forestlands.

-

4)

Our land ownership product indicates that 18.7% of public forest and 81.3% of private and industrial forestland owners, cover 41.5% and 58.5% area of total forestland, respectively. Management practices affected units are represented not only at the stand or local scale, but also will change the forest pattern dramatically at the regional scale. We provided substantial evidence that road networks occupy a substantial proportion of forest. From a forest management perspective, more road landscape area leads to less available land for trees at the macrosystems scale. On the other hand, logging roads and trails are an efficient way to manage forests, which we can see the relatively high road network densities in ecological and production forestry.

This study represents benefits so society in that future management decisions can be evaluated cross scales, taking account of both climate and disturbance regimes. More information on the effects of land ownership and forest management, combined with the detailed road network and a continental coverage land cover maps can aid in thwarting further forest fragmentation by promoting more reasonable road planning by land planners and decision makers.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset and code used during the current study are available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11406612.v1

Abbreviations

- GEE:

-

Google earth engine

- LANDFIRE:

-

Landscape fire and resource management planning tools

- MODIS:

-

Moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer

- NLCD:

-

National land cover database

- NLM:

-

Neutral landscape model

- OSM:

-

OpenStreetMap

- SEUS:

-

Southeastern U.S. Coastal Plain and Piedmont

- VGI:

-

Volunteered geographic information

References

Bailey RG (2004) Identifying ecoregion boundaries. Environ Manag 34(1):S14–S26

Battaglia M, Sands PJ (1998) Process-based forest productivity models and their application in forest management. Forest Ecol Manag 102(1):13–32

Becknell JM, Desai AR, Dietze MC, Schultz CA, Starr G, Duffy PA, Franklin JF, Pourmokhtarian A, Hall J, Stoy PC, Binford MW, Boring LR, Staudhammer CL (2015) Assessing interactions among changing climate, management, and disturbance in forests: a macrosystems approach. BioScience 65(3):263–274

Bennett AF (1991) Roads, roadsides and wildlife conservation: a review. http://worldcat.org/isbn/0949324353. Accessed 22 May 2020

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45(1):5–32

Ciepluch B, Mooney P, Jacob R, Winstanley AC (2009) Using OpenStreetMap to deliver location-based environmental information in Ireland. SIGSPATIAL Special 1(3):7–22

Coffin AW (2007) From roadkill to road ecology: a review of the ecological effects of roads. J Transp Geogr 15(5):396–406

Coghlan G, Sowa R (1997) National forest road system and use. Draft rep. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Engineering Staff, Washington, DC

Davis DE, Colten CE, Nelson MK, Saikku M, Allen BL (2006) Southern United States: an environmental history. ABC-CLIO

Demir M, Hasdemir M (2005) Functional planning criterion of forest road network systems according to recent forestry development and suggestion in Turkey. Am J Environ Sci 1(1):22–28

Douglass JE (1983) The potential for water yield augmentation from forest management in the eastern United States. J Am Water Res Assoc 19(3):351–358

Drever CR, Peterson G, Messier C, Bergeron Y, Flannigan M (2006) Can forest management based on natural disturbances maintain ecological resilience? Can J For Res 36(9):2285–2299

Eker M, Coban HO (2010) Impact of road network on the structure of a multifunctional forest landscape unit in southern Turkey. J Environ Biol 31(1–2):157–168

Faccoli M, Bernardinelli I (2014) Composition and elevation of spruce forests affect susceptibility to bark beetle attacks: implications for forest management. Forests 5(1):88–102

FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) (2013). Highway statistics 2013.

Forman RT, Sperling D, Bissonette JA, Clevenger AP, Cutshall CD, Dale VH, Fahrig L, France RL, Goldman CR, Heanue K, Jones J, Swanson F, Turrentine T, Winter TC (2003) Road ecology: science and solutions. Island Press, Washington

Forman RTT, Alexander LE (1998) Roads and their major ecological effects. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 29:207–231

Forman RTT, Deblinger RD (2000) The ecological road-effect zone of a Massachusetts (U.S.a.) suburban highway. Conserv Biol 14(1):36–46

Fox TR, Jokela EJ, Allen HL (2007) The development of pine plantation silviculture in the southern United States. J For 105(7):337–347

Franklin JF, Forman RTT (1987) Creating landscape patterns by forest cutting: ecological consequences and principles. Landsc Ecol 1(1):5–18

Franklin JF, Mitchell RJ, Palik BJ (2007) Natural disturbance and stand development principles for ecological forestry. Gen tech rep NRS-19. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station

Haines TK, Busby RL, Cleaves DA (2001) Prescribed burning in the south: trends, purpose, and barriers. South J Appl For 25(4):149–153

Hanson C (2010) Southern forests for the future. https://www.wri.org/publication/southern-forests-future. Accessed 22 May 2020

Haynes RW (2002) Forest management in the 21st century: changing numbers, changing context. J For 100(2):38–43

Hijmans RJ, Phillips S, Leathwick J, Elith J, Hijmans MRJ (2015) Package ‘dismo’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dismo/dismo.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020

Hou Z, Xu Q, Nuutinen T, Tokola T (2013) Extraction of remote sensing-based forest management units in tropical forests. Remote Sens Environ 130:1–10

Jiménez-Valverde A, Lobo J M (2007) Threshold criteria for conversion of probability of species presence to either–or presence–absence. Acta Ecol 31(3):361–369

Jin S, Yang L, Danielson P, Homer C, Fry J, Xian G (2013) A comprehensive change detection method for updating the National Land Cover Database to circa 2011. Remote Sens Environ 132:159–175

Josephson H (1989) A history of forestry research in the southern United States. Notes 1462:78 http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/3175. Accessed 22 May 2020

Kurz WA, Dymond CC, Stinson G, Rampley GJ, Neilson ET, Carroll AL, Ebata T, Safranyik L (2008) Mountain pine beetle and forest carbon feedback to climate change. Nature 452(7190):987–990

Marsik M, Staub C, Kleindl W, Fu CS, Hall J, Yang D, Stevens FR, Binford M (2017) PANGAEA. doi: https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.880304. Accessed 22 May 2020

McGarigal K, Romme WH, Crist M, Roworth E (2001) Cumulative effects of roads and logging on landscape structure in the San Juan Mountains, Colorado (USA). Landsc Ecol 16:327–349

Mitchener LJ, Parker AJ (2005) Climate, lightning, and wildfire in the national forests of the southeastern United States: 1989-1998. Phys Geogr 26(2):147–162

Mooney P, Corcoran P, Winstanley AC (2010) Towards quality metrics for OpenStreetMap. Proceedings of the 18th SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems. ACM, San Jose 514–517

Nelson JD, Finn ST (1991) The influence of cut-block size and adjacency rules on harvest levels and road networks. Can J For Res 21(5):595–600

Netherer S, Nopp-Mayr U (2005) Predisposition assessment systems (PAS) as supportive tools in forest management—rating of site and stand-related hazards of bark beetle infestation in the high Tatra Mountains as an example for system application and verification. Forest Ecol Manag 207(1):99–107

Niemelä J (1999) Management in relation to disturbance in the boreal forest. Forest Ecol Manag 115(2):127–134

O’Neill RV, Hunsaker CT, Timmins SP, Jackson BL, Jones KB, Riitters KH, Wickham JD (1996) Scale problems in reporting landscape pattern at the regional scale. Landsc Ecol 11(3):169–180

Ordway-Swisher Biological Station (2015) OSBS User Guide V. http://www.ordway-swisher.ufl.edu/docs/OSBS_User_Guide.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020

Oswalt SN, Smith WB, Miles PD et al (2014) Forest resources of the United States, 2012: a technical document supporting the Forest Service 2010 update of the RPA assessment. Gen tech rep WO-91. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington Office, p 218

Outcalt KW (2000) The longleaf pine ecosystem of the south. Native Plants J 1(1):42–53

Ries L, Fletcher RJ Jr, Battin J, Sisk TD (2004) Ecological responses to habitat edges: mechanisms, models, and variability explained. Ann Rev Ecol Evol Syst 35:491–522

Riitters KH, Wickham JD, Coulston JW (2004) Use of road maps in national assessments of forest fragmentation in the United States. Ecol Soc 9(2):13

Robertson KM, Ostertag TE(2007) Effects of land use on fuel characteristics and fire behavior in pinelands of Southwest Georgia. Proceedings of the 23rd tall timbers fire ecology conference: fire in Grassland & Shrubland Ecosystems, San Diego, California

Rollins MG (2009) LANDFIRE: a nationally consistent vegetation, wildland fire, and fuel assessment. Int J Wildland Fire 18(3):235–249

Saura S, Martinez-Millán J (2000) Landscape patterns simulation with a modified random clusters method. Landsc Ecol 15(7):661–678

Sciaini M, Fritsch M, Scherer C, Simpkins CE (2018) NLMR and landscapetools: An integrated environment for simulating and modifying neutral landscape models in R bioRxiv 307306

Siry JP (2002) Intensive timber management practices. Southern Forest Res Assess 14:327–340

Stanturf JA, Kellison RC, Broerman FS, Jones SB (2003). Productivity of southern pine plantations: where are we and how did we get here?. J Fores 101(3):26–31

Stephens SL, McIver JD, Boerner REJ, Fettig CJ, Fontaine JB, Hartsough BR, Kennedy PL, Schwilk DW (2012) The effects of forest fuel-reduction treatments in the United States. BioScience 62(6):549–560

Turner MG, Wear DN, Flamm RO (1996) Land ownership and land-cover change in the southern Appalachian highlands and the Olympic peninsula. Ecol Appl 6(4):1150–1172

TIGER Cartographic Boundary – Urban Areas, prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau (2015) Available from https://www.census.gov/geo/mapsdatadata/kml/kml_ua.html.

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service (1999) Final environmental impact statement for the land and resource management plans for National Forests in Florida. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd500375.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020

US Fish, Wildlife Service (2006) Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge and Nansemond National Wildlife Refuge Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan. http://www.fws.gov/uploadedFiles/Region_5/NWRS/South_Zone/Great_Dismal_Swamp_Complex/Great_Dismal_Swamp/FinalCCP_GDS.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020

Van der Vaart AW (1998) Asymptotic statistics (Vol. 3). Cambridge University Press, UK

Verbesselt J, Hyndman R, Zeileis A, Culvenor D (2010) Phenological change detection while accounting for abrupt and gradual trends in satellite image time series. Remote Sensing Environ 114(12):2970–2980

Waldrop TA, White DL, Jones SM (1992) Fire regimes for pine-grassland communities in the southeastern United States. Forest Ecol Manag 47(1–4):195–210

Warren DL, Glor RE, Turelli M (2008) Environmental niche equivalency versus conservatism: quantitative approaches to niche evolution. Evolution 62(11):2868–2883

Wear DN, Greis J (2002) Southern forest resource assessment: summary of findings. J For 100(7):6–14

Wear DN, Greis JG (2012) The southern forest futures project: summary report. Gen tech rep SRS-GTR-168. USDA-Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, p 54

Wear DN, Greis JG (2013) The southern forest futures project: technical report. Gen tech rep SRS-GTR-178. USDA-Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, p 542

Wendland KJ, Lewis DJ, Alix-Garcia J, Ozdogan M, Baumann M, Radeloff VC (2011) Regional-and district-level drivers of timber harvesting in European Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Glob Environ Chang 21(4):1290–1300

Zaccarelli N, Li BL, Petrosillo I, Zurlini G (2013) Order and disorder in ecological time-series: introducing normalized spectral entropy. Ecol Indic 28:22–30

Zhang D, Butler BJ, Nagubadi RV (2012) Institutional timberland ownership in the US south: magnitude, location, dynamics, and management. J For 110(7):355–361

Zielstra D, Hochmair HH (2011) Digital street data: Free versus proprietary. GIM Int 25(7):29–33

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement is made of the assistance of Dr. Michael Binford and Dr. Peter Waylen, Department of Geography, University of Florida, for English writing and reviewing, for suggestions and discussion. Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation Macrosystems Biology Program Grant EF #1241860.

Funding

We acknowledge funding from the Macrosystems Biology Program Grant EF #1241860 from United States National Science Foundation (NSF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YD and FC conceptualized the idea for the study, FC generated the SEUS forest ownership database; YD performed data analysis and led the writing of the manuscript; FC critically reviewed the data analysis, and contributed substantially to the writing. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, D., Fu, CS. Mapping regional forest management units: a road-based framework in Southeastern Coastal Plain and Piedmont. For. Ecosyst. 8, 17 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-021-00289-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-021-00289-w