Abstract

Background

This translational study explores multi-tracer PET imaging for the non-invasive detection of the IDH1 mutation which is a positive prognostic factor in glioma.

Methods

U87 human high-grade glioma (HGG) isogenic cell lines with or without the IDH1 mutation (CRISP/Cas9 method) were stereotactically grafted into rat brains, and examined, in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo. PET imaging sessions, with radiotracers specific for glycolytic metabolism ([18F]FDG), amino acid metabolism ([18F]FDopa), and inflammation ([18F]DPA-714), were performed sequentially during 3–4 days. The in vitro radiotracer uptake was expressed as percent per million cells. For each radiotracer examined in vivo, static analyses included the maximal and mean tumor-to-background ratio (TBRmax and TBRmean) and metabolic tumor volume (MTV). Dynamic analyses included the distribution volume ratio (DVR) and the relative residence time (RRT) extracted from a reference Logan model. Ex vivo analyses consisted of immunological analyses.

Results

In vitro, IDH1+ cells (i.e. cells expressing the IDH1 mutation) showed lower levels of [18F]DPA-714 uptake compared to IDH1- cells (p < 0.01). These results were confirmed in vivo with lower [18F]DPA-714 uptake in IDH+ tumors (3.90 versus 5.52 for TBRmax, p = 0.03). Different values of [18F]DPA-714 and [18F] FDopa RRT (respectively 11.07 versus 22.33 and 2.69 versus − 1.81 for IDH+ and IDH- tumors, p < 0.02) were also observed between the two types of tumors. RRT [18F]DPA-714 provided the best diagnostic performance to discriminate between the two cell lines (AUC of 100%, p < 0.01). Immuno-histological analyses revealed lower expression of Iba-1 and TSPO antibodies in IDH1+ tumors.

Conclusions

[18F]DPA-714 and [18F] FDopa both correlate with the presence of the IDH1 mutation in HGG. These radiotracers are therefore good candidates for translational studies investigating their clinical applications in patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutation is a key molecular feature of the World Health Organization (WHO) Central Nervous System (CNS) tumor classification. This molecular alteration is a significant biomarker in the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of gliomas [1, 2]. Gliomas expressing the IDH1 mutation are associated with better chemo- and radiotherapy responses and longer patient survival periods [2,3,4]. This IDH1 mutation leads to an intracytoplasmic accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) [5] which alters overall tumor metabolism [6].

Whilst several studies have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to attempt to non-invasively characterize the IDH1 mutation in gliomas ([4, 7,8,9,10,11,12], the potential for positron emission tomography (PET) as a complementary metabolic imaging tool, is a growing field [13, 14]. PET imaging allows to depict different patho-physiological mechanisms to study changes in cellular metabolism. The diagnostic information acquired with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) allows to investigate glycolytic pathways albeit that this radiotracer is poorly suited to neuro-oncology applications owing to its high physiologic uptake by healthy brain tissue [14]. Amino acid PET tracers, such as 18F-fluoroethyltyrosine ([18F]-FET) or 18F-fluorodihydroxyphenylalanine ([18F]FDopa) however bind to the L-type amino acid transporter-1 (LAT-1) and may be used to specifically investigate amino-acid metabolism. These amino-acid PET radiotracers exhibit reduced uptake in healthy brain tissue, thereby enabling more accurate characterization of gliomas [15]. The [18F] FDopa radiotracer is widely used in the US and some European countries. It is cost-effective because, unlike 18F-FET, it can be used for other clinical neurology or oncology indications e.g., to detect parkinsonian disorders or neuroendocrine neoplasms [16]. Although IDH1 mutation status and its correlation with amino acid PET data remains ambiguous and heterogeneous [17], some recent analyses recommend using dynamic analyses for predicting the IDH mutation [18, 19]. New generation radiotracers have been developed to better characterize other glioma properties by PET imaging. Notable among these is the tumor inflammation specific [18F]DPA-714, a ligand of the translocator protein (TSPO), expressed in glioma cells [20,21,22]. It is this advance that has recently lead to reports of TSPO PET radiotracers as suitable options for the characterization of gliomas at initial diagnosis [23]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has to date combined multi-tracer static and dynamic PET acquisitions to investigate the metabolic changes induced by expression of the IDH1 mutation in gliomas.

Currently, preclinical studies represent the sole means of investigating the IDH1 mutation phenotype, independently of other mutations and tumor characteristics, in vivo. Previous preclinical studies have attempted to investigate the overexpression of the IDH1 mutation in vivo [24,25,26,27] although none with the original objective of specifically investigating its pathophysiological expression by introducing the mutation in the well characterized U87 human high-grade gliomas (HGG) cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9. This innovative genetic approach allows to evaluate the effects of the isolated, basal expression of the IDH1 mutation. We previously characterized in vivo physiologic and metabolic changes of the IDH1 mutation using multiparametric MRI and spectroscopy [28]. Such multiple MRI sequences are nevertheless difficult to apply in clinical routine practice which underpins the recent interest in currently available PET radiotracers, particularly radiotracers specific for inflammation and metabolism, that may be able to inform about additional tumor properties and more targeted pathophysiological mechanisms.

The aim of our current study is to characterize in vitro and in vivo metabolic changes induced by the expression of the IDH mutation in U87 human derived HGG cell lines in the rat orthograft model, by using multiparametric and multitracer PET imaging specific for glycolytic metabolism ([18F]FDG), amino-acid metabolism ([18F]FDopa) and tumor inflammation ([18F]DPA-714) and corroborating this data with ex vivo immunological analyses.

Methods

U87-MG human derived HGG cell lines

U87 human derived HGG cell lines IDH1-mutated (IDH1+) and non IDH1-mutated (IDH1-) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection® (ATCC, HTB-14IG and HTB-14). The two cells lines were cultured under standard conditions as previously described [28].

Animal models

IDH1+ and IDH1- cells (5 × 104 cells per animal) were implanted into the right caudate nucleus of the brain of athymic male nude rats (200–250 g; RH-Foxn1rnu; Envigo Gannat, France) as previously described [28].

After completing the imaging some of the anesthetized animals were sacrificed, by decapitation, for histological analysis (N = 20 IDH1+ and N = 14 IDH1-).

Radiochemistry

[18F] FDG (FLUCIS®) and [18F] FDopa (DOPACIS®) were purchased from Curium (Nancy, FRANCE). [18F]DPA-714 radiosynthesis was implemented on the AIO® synthesizer to produce [18F]DPA-714 by nucleophilic substitution of the tosylated precursor OTs-DPA-714 (Pharmasynth, Estonia), as described in the literature [29].

In vitro study

The IDH1+ and IDH1- U87 human derived HGG cells were resuspended in HBSS at a concentration of 2 × 105/mL, and incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2/95% air) with 1 MBq/mL of each individual radiotracer for 30-, 60- and 120-min. Tracer uptake was stopped with the addition of ice-cold phosphate-buffered-saline (PBS). The cell substrate was then washed twice in cold PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of cold HBSS. The radioactivity, expressed as counts per minute and corrected for individual radiotracer decay, was measured using a calibrated gamma counter (Wizard, PerkinElmer®, France). Cell uptake, expressed as uptake per million cells, was determined by trypan blue. Individual radiotracer experiments were performed in duplicate for each of the three time points (N = 6) examined per radiotracer and per cell line.

In vivo study

PET recordings were obtained with a camera dedicated to small animal studies (Inveon, Siemens Preclinical Solutions®, Knoxville, USA).

Two sets of rat brain acquisitions were performed, static acquisitions only for the first set of rats and dynamic and static acquisitions for the second set of rats.

A flowchart of the in vivo procedure is detailed in Fig. 1.

Flowchart of experimental design. Rats were orthotopically implanted with U87 human derived HGG IDH1+ or IDH1- cell lines. After tumor outgrowth, imaging sessions were performed sequentially during 3–4 days. The order in which radiotracers were imaged was predicated by their availability and was as follows [18F] FDG PET on the 14th day post tumor cell graft (p-g), MRI and [18F] FDopa on the 15th day p-g, [18F]DPA-714 between the 16th day and 17th day p-g. Rats were subsequently sacrificed for tumor histology analyses

For static acquisitions, a 30-min PET scan was performed with [18F] FDG (injected activity of 74 MBq/mL) at 60 min p-i [30], [18F] FDopa (30 MBq/mL) at 30 min p-i [31] as recommended in the literature [32]. For [18F]DPA-714 radiotracer, a 20 min PET scan was acquired at 60 min p-i with an injected activity of 30 MBq/mL [33]. All PET images were reconstructed using the ordered-subset expectation maximization 3D algorithm (OSEM3D, 4 iterations, 16 subsets, zoom 1) together with scatter and attenuation corrections based on the transmission scan using a 57Co source measurement. The final voxel size was 0.77 × 0.77 × 0.79 mm3.

List-mode acquisitions were started a few seconds prior to the tracer injection with a 120 min acquisition for all radiotracers, and all acquired PET data were subsequently reconstructed in 27 consecutive frames (i.e., 5 frames × 120-s, 22 frames × 300-s). Reconstructed parameters were similar to those reported for static acquisitions.

MRI was performed on a 3Tesla scanner (Prisma, Siemens Healthineers®, Erlangen, Germany) with an 8-channel volume coil (Rapid Biomedical GmbH®, Rimpar, Germany). T2-weighted (T2-w) anatomical images were acquired using a Turbo Spin-Echo sequence (repetition time (TR)/echo-time (TE) = 2500/61 ms, voxel size = 255 × 255 × 1000 μm3, 24 slices, field of view (FOV) = 49 × 49 mm2, 8 averages) to define tumor volumes on the 15th day p-g.

Volumes of interest (VOIs) were defined on static PET and PET/T2-w MRI fused images with dedicated software (Inveon Research Workplace 4.1, Siemens®, Knoxville, USA) and centered on the maximal tumor uptake. From these VOIs, tumors VOIs were deduced from metabolic tumor volumes defined in the literature: with a 0.8 ratio of healthy brain tissue for [18F] FDG, a 1.3 ratio for [18F] FDopa [14], and a 1.8 ratio for [18F]DPA-714 [23]. The normal brain reference was defined as a symmetrical VOI in the contralateral healthy brain.

Maximum and mean Standardized Uptake Values (SUVmax and SUVmean, respectively) were determined from tumor VOIs. A partial volume effect correction (PVC) was applied to tumor SUVmax and SUVmean values using the maximum and mean recovery coefficients (RCs) corresponding to the tumor volume, respectively. For each radiotracer, RCs were computed from phantom experiments using spherical inserts (volume range: [0.031 mL; 0.25 mL]) and a sphere-to-background contrast corresponding to the mean contrast observed between tumor and healthy brain. After PVC, tumor-to-normal-brain (TBR) ratios were computed as SUVmean or SUVmax of the tumor uptake divided by the SUVmean of the normal brain (TBRmean and TBRmax). VOIs previously defined on static images, were identically defined on dynamic images. For dynamic analyses, reference Logan models were generated for [18F] FDopa and [18F]DPA-714 as they have been shown to be adapted to the pharmacokinetics of these radiotracers [34, 35]. Two parameters, with regression starting at 30 min, were extracted from this model, namely the distribution volume ratio (DVR) and the relative residence time (RRT) computed respectively as the slope and the negative of the intercept. Additionally, the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) [36] was further calculated at the individual rat level, to measure the index of similarity between different metabolic volumes obtained with different PET tracers.

The volume of interest (VOI) was manually delineated on the T2-w images of the MRIs of each rat brain to determine the tumor volume.

Ex vivo study

Tumor tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Five-μm paraffin sections were incubated in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) for 20 min at 97 °C for dewaxing and antigen retrieval. Sections were stained with the following primary antibodies: anti-GLUT-1 (1:600, NB-22-3291, Neo Biotech), anti-CD-98 (anti-LAT-1) (1:500, LS-C4853000, LSBio), anti-Iba1 (1:100, anti-AIF1, ABIN2192043, antibodies-online.com) and anti-TSPO (1:200, BS9815M, Bioworld technology) along with Dako Autostainer Plus (Dako) and Flex+. All sections were examined by 2 observers (C.P. and A.C. or B.M.) on an Olympus BX 51 microscope and quantitative analysis was performed with the Image J image-processing software (Version 1.48). GLUT-1 hotspots were counted in one single light microscope field at 40x magnification. A staining score was applied to TSPO, Iba-1 and CD-98 with intensities defined as 0: no staining, 1: light, 2: moderate or strong with < 50% of cells staining, 3: strong with > 50% of cells staining.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM, SPSS Statistics version 25.0) and R version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The two-tailed significance level was set at p < 0.05. As the number of animals examined was not sufficient to assume a normal distribution, continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges, except for in vitro variables which were expressed as means and standard deviations. PET and MRI parameters were compared using Mann Whitney with adjusted p values (Benjamini Hochberg correction) to reduce the false discovery rate. The ability of each individually extracted parameter to predict an IDH mutation was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from which area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity and accuracy were computed. The optimal threshold was determined by selecting the point on the curve closest to (0,1).

Results

In-vitro study

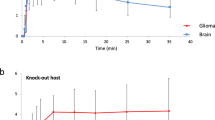

Figure 2 summarizes results of the in vitro study. There was no difference in cell uptake activity between IDH1+ and IDH1- tumors for [18F] FDG and the [18F] FDopa (p > 0.21). In contrast, IDH1+ cells exhibited significantly lower uptakes of [18F]DPA-714 at all concentration measurement time points when compared to IDH1- cells (0.71, 0.57, 0.53% of uptake/million cells at 30, 60, 120 min versus 1.40, 1.58 and 1.81% of uptake/million cells, p < 0.01).

Histograms of in vitro multi-tracer analyses for [18F] FDG (a), [18F] FDopa (b) and [18F]DPA-714 (c) uptake in U87 human derived HGG IDH1+ and IDH1- cell lines after 30, 60, and 120 min incubation (n = 6 measurements for each individual tracer per time point). Radiotracer uptake was expressed as percent uptake per million tumor cells. Mann Whitney tests with p < 0.05 as significant

In-vivo study

Rat population

For static acquisitions, we induced 24 IDH1+ and 28 IDH1– rat brain tumors. For static and dynamic acquisitions of the second set of rats, 15 rats with IDH1+ and 14 rats with IDH1- tumors, were imaged. A detailed Table (Table S1) of available imaging session samples for each radiotracer with both static and dynamic datasets is presented in the additional file.

MRI and PET data analyses

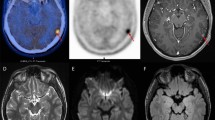

IDH1+ and IDH1– tumors grew to similar volumes, 23.35 [14.40; 66.25] mm3 versus 27.95 [18.00; 77.57] mm3, respectively (p = 0.83). PET results are summarized in Table 1. No significant difference between IDH1+ and IDH1- tumors was observed for [18F] FDG and [18F] FDopa static acquisitions (p ≥ 0.83). When compared to IDH1- tumors, IDH1+ tumors were however characterized by a significantly decreased [18F]DPA-714 TBRmax (3.90 [3.29; 4.67] vs.5.52 [4.72; 6.72], p = 0.03). In addition, the IDH1+ tumor characteristics were associated with significantly higher RRT in [18F] FDopa and lower RRT in [18F]DPA-714 (respectively 2.70 [1.45; 3.23] min for IDH+ versus − 1.81 [− 3.04; − 0.75] min for IDH-, p = 0.03 and 11.07 [7.09; 15.69] min for IDH+ versus 22.33 [20.68; 23.76] min for IDH-, p < 0.01). As displayed in Table 2, [18F]DPA-714 RRT provided the best diagnostic performances for identifying the IDH mutation (AUC of 1 [1;1]). Representative tumors imaged with MRI and multi-tracer PET are shown in Fig. 3. Examples of tumor activity curves and dynamic analyses are provided in Fig. 4.

Dice

The only exploitable results from the DICE coefficients (N ≥ 5 for direct comparisons between the two radiotracers) showed a low DICE coefficient between [18F] FDopa and [18F]DPA-714 (n = 9, 0.38 [0.26; 0.55]).

Post-sacrifice analyses

There were no significant differences for GLUT-1, with hotspot median values of 28.00 [18.00; 38.00] for IDH1+ (N = 9) and 32.00 [26.75; 35.75] for IDH1- (N = 10), for LAT-1 staining with an average score of 2 for both tumor types (N = 7 IDH1+ and N = 11 IDH1-). However, Iba-1 and TSPO receptors showed lower staining in IDH+ compared to IDH- with respective average scores of 1.35 vs. 1.9 for Iba-1 and < 1 vs. 1.2 for TSPO (N = 3 IDH1+ and N = 5 IDH1-). Figure 5 shows a series of representative Iba-1 and TSPO staining patterns.

Discussion

In this preclinical multiparametric and multi-tracer PET study, the IDH1 mutation is associated with lower glioma uptake of [18F]DPA-714 in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo. In addition, the dynamic RRT [18F] FDopa parameter is also associated with the presence of the IDH1 mutation. These preclinical results are consistent with recent results obtained in human patients [37, 38]. In contrast, no significant differences were observed between IDH1+ and IDH1- tumors for static [18F] FDG and [18F] FDopa acquisitions.

Our study used an animal model based on human derived HGG cell lines. Even though the IDH mutation is predominantly observed in glioma patients with low-grade tumors, one of the advantages of using a high-grade tumor model in preclinical studies is to reach a high enough rate of tumor growth potential in these models to accentuate any potential differences in uptake of the PET radiotracers investigated. Several experimental studies have endeveoured to develop candidate radiotracers for noninvasive PET imaging of the IDH1 mutation but most of these yielded inconclusive results due to instability of the radiotracer in blood, lack of radiotracer selectivity or because experiments were not performed under representative physiologic conditions [39,40,41]. Our current study is original since it employs a combination of three different, easily clinically transposable, PET radiotracers to investigate specific pathophysiological pathways of glioma development that may be uniquely impacted by the IDH1 mutation, using an innovative application of CRISPR/Cas9.

The radiotracer of interest from our current study is [18F]DPA-714, because it targets TSPO receptors which are upregulated during neuroinflammation. A lower uptake of this radiotracer was observed in IDH1+ tumors in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo thus confirming the specificity of this radiotracer. The lower tracer uptake values are consistent with the reduced level of neuroinflammation and by extension the decreased aggressiveness of IDH+ tumors, which is in complete accordance with reports from the literature [38, 42]. Our recent study, which investigated multiparametric MRI, also found a spectroscopic profile of lower aggressiveness for IDH+ tumors, which further confirms results obtained in the current study [28]. Other mechanisms related to the IDH mutation may be suggested albeit based on assumptions that cannot be substantiated from our current data. In terms of metabolism, the IDH1 mutation may for instance lead to an intracytoplasmic accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) [5]. This may in turn alter the glioma epigenome by increasing DNA methylation [43, 44], activating cellular malignant transformation [45, 46], thereby altering overall tumor metabolism by inducing a downregulation of phospholipid biosynthesis [6, 47,48,49]. Such a mechanism may thus contribute to the less aggressive profile of tumors with an IDH mutation. Although amino-acid radiotracers have been increasingly studied in neuro-oncology [50], TSPO imaging seems to be particularly promising because it identifies glioma physio-pathological mechanisms that are distinct from those invoked by amino-acid tracers. This could explain the weak DICE index between TSPO and amino-acid uptake observed in our current study even though it was obtained from a small number of rats. TSPO imaging and IDH mutational status confer a trend towards higher 18F-GE-180-uptake in IDH-wild-type gliomas in the overall group, albeit that this trend was not confirmed in identical WHO grade gliomas [23]. Interestingly, both static and dynamic parameters for [18F]DPA-714 provided high predictive performance values to discriminate between the two tumor types, the best performances being obtained with the dynamic RRT [18F]DPA-714 (AUC of 1 [1;1]). Blood brain barrier (BBB) penetrance remains an issue for TSPO imaging [22] but is not a limitation for brain tumors in general or for gliomas per se since the brain blood barrier is disrupted in the vast majority of HGGs. Our previous study showed that contrast-enhancements were observed in our animal models, confirming that the BBB was disrupted [28]. In any case, our current study underlines the fact that using multiparametric PET, i.e. combining static and dynamic data, is very helpful to extract a maximum of information from PET imaging [37].

The second radiotracer of choice is the amino-acid PET [18F] FDopa radiotracer. Our current results are consistent with those obtained in human patients where dynamic [18F] FDopa PET parameters were the only factors that predicted the IDH mutation, whether it be compared to SUV-related or textural features [18, 51]. These previous results obtained in human patients could be influenced by multiple other histological or molecular cofounding factors. In our current study, the only difference between the two cell lines is the IDH mutation status. Since dynamic [18F] FDopa PET parameters were associated with the IDH mutation, unlike any of the in vitro or ex vivo variables, it appears that dynamic parameters predominantly detect perfusion phase differences between the IDH1+ and IDH1- cell types. Indeed, wash-in-wash-out phases are typically observed in aggressive IDH-wildtype gliomas, which may correspond to tumors that not only express high concentrations of LAT transporters but also tumors that are characterized by more extensive tracer perfusion as discussed in our previous publication [34]. In contrast, our [18F] FDG PET results are somewhat less surprising, and consistent with reports in the literature, since this radiotracer does not allow to differentiate tumor tissue from healthy brain cortex because of its physiologic uptake in healthy brain tissue, which limits the potential usefulness of this radiotracer in neuro-oncology [13] .

Our study does have several inherent limitations. Even though our tissue staining results confirmed the PET results, neo-angiogenesis and microglia/macrophages (GAMs), may have contributed to the TSPO signal [22]. This was not specifically tested in our current study. Further preclinical studies with post-autopsy histo-radiography analyses are required to better define the specific regions of radiotracer uptake. Moreover, it is known that TSPO polymorphisms can alter radiotracer uptake, which would limit the radiotracer’s potential usefulness in translational human studies. Our current study is also limited by the fact that not all rats were able to be PET imaged for all three radiotracers, due to the differing availabilities of individual radiotracers delivered to the lab at the time. In addition, although the volumes of IDH1+ tumors were statistically similar to IDH1- tumors, tumor growth varied between the groups and between radiotracer acquisitions. The concordance of in vitro, in vivo and ex vivo results at least for the [18F]DPA-714 PET nevertheless suggests that the contribution of any such potentially confounding effects is limited.

Conclusion

To summarize, [18F]DPA-714 and [18F] FDopa are two PET radiotracers that are associated with the presence of the IDH1 mutation in HGG in this preclinical study. Their complementarity may lead to future translational studies exploring their clinical applications in patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- DSC:

-

Dice similarity coefficient

- DVR:

-

Distribution volume ratio

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- HGG:

-

Human high-grade glioma

- IDH:

-

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- LAT-1:

-

L-type amino acid transporter-1

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTV:

-

Metabolic tumor volume

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered-saline

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- PVC:

-

Partial volume effect correction

- RCs:

-

Recovery coefficients

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating curves

- RRT:

-

Relative residence time

- SUVmax :

-

Maximum standardized uptake values

- SUVmean :

-

Mean standardized uptake values

- TBRmax :

-

Maximal tumor-to-background ratio

- TBRmean :

-

Mean tumor-to-background ratio

- TE:

-

Echo-time

- TR:

-

Repetition time

- TSPO:

-

Translocator protein

- VOI:

-

Volume of interest

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2016;131:803–20.

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro-Oncol. 2021;23:1231–51.

SongTao Q, Lei Y, Si G, YanQing D, HuiXia H, XueLin Z, et al. IDH mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in secondary glioblastoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:269–73.

Tran AN, Lai A, Li S, Pope WB, Teixeira S, Harris RJ, et al. Increased sensitivity to radiochemotherapy in IDH1 mutant glioblastoma as demonstrated by serial quantitative MR volumetry. Neuro-Oncol. 2014;16:414–20.

Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2010;465:966.

Reitman ZJ, Jin G, Karoly ED, Spasojevic I, Yang J, Kinzler KW, et al. Profiling the effects of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations on the cellular metabolome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3270–5.

Emir UE, Larkin SJ, de Pennington N, Voets N, Plaha P, Stacey R, et al. Noninvasive quantification of 2-Hydroxyglutarate in human gliomas with IDH1 and IDH2 mutations. Cancer Res. 2016;76:43–9.

Chaumeil MM, Larson PEZ, Yoshihara HAI, Danforth OM, Vigneron DB, Nelson SJ, et al. Non-invasive in vivo assessment of IDH1 mutational status in glioma. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2429.

Lu HT, Xing W, Zhang YW, Qin HP, Wu RH, Ding JL. The value of DCE-MRI in predicting IDH gene mutation of high-grade gliomas. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;99:3105–9.

Tiwari V, Mashimo T, An Z, Vemireddy V, Piccirillo S, Askari P, et al. In vivo MRS measurement of 2-hydroxyglutarate in patient-derived IDH-mutant xenograft mouse models versus glioma patients. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84(3):1152–60.

Pope WB, Prins RM, Albert Thomas M, Nagarajan R, Yen KE, Bittinger MA, et al. Non-invasive detection of 2-hydroxyglutarate and other metabolites in IDH1 mutant glioma patients using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neuro-Oncol. 2012;107:197–205.

Nagashima H, Tanaka K, Sasayama T, Irino Y, Sato N, Takeuchi Y, et al. Diagnostic value of glutamate with 2-hydroxyglutarate in magnetic resonance spectroscopy for IDH1 mutant glioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2016;18:1559–68.

Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B, Galldiks N, Soffietti R, Kim MM, et al. Response assessment in neuro-oncology working group and European Association for Neuro-Oncology recommendations for the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. 2016;18:1199–208.

Law I, Albert NL, Arbizu J, Boellaard R, Drzezga A, Galldiks N, et al. Joint EANM/EANO/RANO practice guidelines/SNMMI procedure standards for imaging of gliomas using PET with radiolabelled amino acids and [18F]FDG: version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:540–57.

Chen W. Clinical applications of PET in brain tumors. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2007;48:1468–81.

Verger A, Kas A, Darcourt J, Chinot O, Taillandier L, Hoang Xuan K, et al. Joint SFMN/ANOCEF focus on 18F-FDOPA PET imaging in glioma: current applications and perspectives. Médecine Nucl. 2020;44:164–71.

Verger A, Taieb D, Guedj E. Is the information provided by amino acid PET radiopharmaceuticals clinically equivalent in gliomas? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1408–10.

Zaragori T, Oster J, Roch V, Hossu G, Chawki MB, Grignon R, et al. 18F-FDOPA PET for the non-invasive prediction of glioma molecular parameters: a radiomics study. J Nucl Med. 2022;63(1):147–57.

Vettermann F, Suchorska B, Unterrainer M, Nelwan D, Forbrig R, Ruf V, et al. Non-invasive prediction of IDH-wildtype genotype in gliomas using dynamic 18F-FET PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(12):2581–9.

Roncaroli F, Su Z, Herholz K, Gerhard A, Turkheimer FE. TSPO expression in brain tumours: is TSPO a target for brain tumour imaging? Clin Transl Imaging. 2016;4:145–56.

Miettinen H, Kononen J, Haapasalo H, Helén P, Sallinen P, Harjuntausta T, et al. Expression of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor and diazepam binding inhibitor in human astrocytomas: relationship to cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2691–5.

Zinnhardt B, Roncaroli F, Foray C, Agushi E, Osrah B, Hugon G, et al. Imaging of the glioma microenvironment by TSPO PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;49(1):174–85.

Unterrainer M, Fleischmann DF, Vettermann F, Ruf V, Kaiser L, Nelwan D, et al. TSPO PET, tumour grading and molecular genetics in histologically verified glioma: a correlative 18F-GE-180 PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1368–80.

Shi J, Zhao Y, Yuan Y, Wang C, Xie Z, Gao X, et al. The expression of IDH1 (R132H) is positively correlated with cell proliferation and angiogenesis in glioma samples. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi Chin J Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;32:360–3.

Lazovic J, Soto H, Piccioni D, Lo Ru JR, Li S, Mirsadraei L, et al. Detection of 2-hydroxyglutaric acid in vivo by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in U87 glioma cells overexpressing isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 mutation. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;14:1465–72.

Shi J, Sun B, Shi W, Zuo H, Cui D, Ni L, et al. Decreasing GSH and increasing ROS in chemosensitivity gliomas with IDH1 mutation. Tumour Biol J Int Soc Oncodevelopmental Biol Med. 2015;36:655–62.

Bralten LBC, Kloosterhof NK, Balvers R, Sacchetti A, Lapre L, Lamfers M, et al. IDH1 R132H decreases proliferation of glioma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:455–63.

Clément A, Doyen M, Fauvelle F, Hossu G, Chen B, Barberi-Heyob M, et al. In vivo characterization of physiological and metabolic changes related to isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutation expcression by multiparametric MRI and MRS in a rat model with orthotopically grafted human-derived glioblastoma cell lines. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4490.

Kuhnast B, Damont A, Hinnen F, Catarina T, Demphel S, Le Helleix S, et al. [18F]DPA-714, [18F]PBR111 and [18F]FEDAA1106-selective radioligands for imaging TSPO 18 kDa with PET: automated radiosynthesis on a TRACERLAb FX-FN synthesizer and quality controls. Appl Radiat Isot Data Instrum Methods Use Agric Ind Med. 2012;70:489–97.

Belloli S, Brioschi A, Politi LS, Ronchetti F, Calderoni S, Raccagni I, et al. Characterization of biological features of a rat F98 GBM model: a PET-MRI study with [18F] FAZA and [18F]FDG. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:831–40.

Verhoeven J, Bolcaen J, De Meulenaere V, Kersemans K, Descamps B, Donche S, et al. Technical feasibility of [18F] FET and [18F] FAZA PET guided radiotherapy in a F98 glioblastoma rat model. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2019;14:89.

Watabe T, Ikeda H, Nagamori S, Wiriyasermkul P, Tanaka Y, Naka S, et al. 18F-FBPA as a tumor-specific probe of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1): a comparison study with 18F-FDG and 11C-methionine PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:321–31.

Tang D, Li J, Nickels ML, Huang G, Cohen AS, Manning HC. Preclinical Evaluation of a Novel TSPO PET Ligand 2-(7-Butyl-2-(4-(2-[18F]Fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-5-Methylpyrazolo [1,5-a]Pyrimidin-3-yl)-N,N-Diethylacetamide (18F-VUIIS1018A) to Image Glioma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21:113–21.

Zaragori T, Doyen M, Rech F, Blonski M, Taillandier L, Imbert L, et al. Dynamic 18F-FDopa PET imaging for newly diagnosed gliomas: is a Semiquantitative model sufficient? Front Oncol. 2021;11:735257.

Golla SSV, Boellaard R, Oikonen V, Hoffmann A, van Berckel BNM, Windhorst AD, et al. Parametric binding images of the TSPO ligand 18F-DPA-714. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2016;57:1543–7.

Zijdenbos AP, Dawant BM, Margolin RA, Palmer AC. Morphometric analysis of white matter lesions in MR images: method and validation. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1994;13:716–24.

Ginet M, Zaragori T, Marie P-Y, Roch V, Gauchotte G, Rech F, et al. Integration of dynamic parameters in the analysis of 18F-FDopa PET imaging improves the prediction of molecular features of gliomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1381–90.

Unterrainer M, Fleischmann DF, Diekmann C, Vomacka L, Lindner S, Vettermann F, et al. Comparison of 18F-GE-180 and dynamic 18F-FET PET in high grade glioma: a double-tracer pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:580–90.

Chitneni SK, Yan H, Zalutsky MR. Synthesis and evaluation of a 18F-labeled Triazinediamine analogue for imaging mutant IDH1 expression in gliomas by PET. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2018;9:606–11.

Chitneni SK, Reitman ZJ, Spicehandler R, Gooden DM, Yan H, Zalutsky MR. Synthesis and evaluation of radiolabeled AGI-5198 analogues as candidate radiotracers for imaging mutant IDH1 expression in tumors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:694–9.

Koyasu S, Shimizu Y, Morinibu A, Saga T, Nakamoto Y, Togashi K, et al. Increased 14C-acetate accumulation in IDH-mutated human glioblastoma: implications for detecting IDH-mutated glioblastoma with 11C-acetate PET imaging. J Neuro-Oncol. 2019;145:441–7.

Vlodavsky E, Soustiel JF. Immunohistochemical expression of peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in human astrocytomas and its correlation with grade of malignancy, proliferation, apoptosis and survival. J Neuro-Oncol. 2007;81:1–7.

Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim S-H, et al. Oncometabolite 2-Hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30.

Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, Rohle D, Turcan S, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature. 2012;483:474–8.

Yang H, Ye D, Guan K-L, Xiong Y. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in tumorigenesis: mechanistic insights and clinical perspectives. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5562–71.

Masui K, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. Cancer metabolism as a central driving force of glioma pathogenesis. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2016;33:161–8.

Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Viswanath P, Eriksson P, Chaumeil MM, Pieper RO, Phillips JJ, et al. Metabolic Reprogramming in Mutant IDH1 Glioma Cells. Ulasov I, editor. Plos One. 2015;10:e0118781.

Lita A, Pliss A, Kuzmin A, Yamasaki T, Zhang L, Dowdy T, et al. IDH1 mutations induce organelle defects via dysregulated phospholipids. Nat Commun. 2021;12:614.

Viswanath P, Radoul M, Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Ong WQ, Luchman HA, Cairncross JG, et al. 2-Hydroxyglutarate-mediated autophagy of the endoplasmic reticulum leads to an unusual downregulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in mutant IDH1 gliomas. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2290–304.

Verger A, Arbizu J. Law I. Role of amino-acid PET in high-grade gliomas: limitations and perspectives. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;62 Cited 13 Oct 2021. Available from: https://www.minervamedica.it/index2.php?show=R39Y2018N03A0254.

Verger A, Imbert L, Zaragori T. Dynamic amino-acid PET in neuro-oncology: a prognostic tool becomes essential. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-021-05530-w.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Petra Neufing for critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. and A.V. designed the study. A.C., R.F., O.O., E.R. and B.M. performed the experiments. A.C., T.Z., E.R. and B.M. provided data analysis. A.C. and A.V. wrote the manuscript. And T.Z., M.B., C.C., E.R., F.M., M.B-H., C.P. and M.D. reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All protocols were approved by the Lorraine Ethics Committee N°66 in accordance with the Guidelines of the Directive 2010/63/EU (APAFIS no. 14056–2018031316365081).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Clément, A., Zaragori, T., Filosa, R. et al. Multi-tracer and multiparametric PET imaging to detect the IDH mutation in glioma: a preclinical translational in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo study. Cancer Imaging 22, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-022-00454-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-022-00454-6