Abstract

Background

Cholangitis is an inflammatory process of the biliary tract with a wide range of clinical manifestations and it is not always considered in the differential diagnosis in asymptomatic patients. To the best of our knowledge there is no previous report in the English literature of focal cholangitis manifesting exclusively as liver parenchymal changes mimicking liver metastasis in asymptomatic patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and history of manipulation of the biliary tree. The purpose of this article is to present six cases of subclinical focal cholangitis mimicking liver metastasis in asymptomatic patients with history of PDAC and biliary tree intervention.

Case presentation

There are six cases with new hepatic lesions detected on follow-up scans in asymptomatic patients with history of PDAC and manipulation of biliary tree. Overall seven lesions were detected, all of them were on the liver periphery, five were hypovascular and two were hypervascular. None of those patients had elevation of CA 19.9 compared with the previous exams. The three patients that had magnetic resonance imaging presented restriction on diffusion weighted imaging and high signal intensity on T2-weighted image. Two patients underwent liver biopsy, which showed only inflammatory changes. All patients were treated with antibiotics and underwent imaging follow-up, which demonstrated resolution of the lesions. None of the patients showed imaging or clinical signs of disease progression during this interval.

Conclusion

Radiologists and oncologists need to be aware of the possibility of focal cholangitis causing hepatic lesions mimicking neoplasia in patients with history of biliary tree intervention, even in the absence of clinical symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cholangitis is an inflammatory process of the biliary tract with a wide range of causes and heterogeneous clinical manifestations [1]. It can occur due to different infectious and noninfectious conditions, with its most common cause being biliary obstruction secondary to either tumour or bile duct stones. The sphincter of Oddi maintains sterility of the biliary ducts by preventing bacterial transposition from the duodenum [2]. Biliary tree intervention, such as biliary duct stenting, papillotomy, and biliodigestive anastomosis, is common in biliopancreatic disorders, and it is known to allow microorganisms to ascend into the biliary tree, increasing the risk of cholangitis [3].

Clinical manifestations of cholangitis may vary widely, from asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic to life-threatening scenarios. The classical Charcot’s triad (jaundice, fever and pain) and Reynolds pentad (when shock and lethargy are included) are not always present and make the clinical diagnosis challenging [4]. This can lead to delayed diagnosis or even misdiagnosis. Moreover, the imaging findings are nonspecific and can be due to bile duct or liver parenchyma abnormalities [5]. The most frequent bile duct changes are: (a) dilatation of biliary tree, which can be central, diffuse, or segmental, (b) thickening and enhancement of ductal walls, and (c) pneumobilia [5]. The liver parenchymal abnormalities are related to inflammatory process, causing dilatation of the peribiliary venous plexus, and to increased arterial flow [6, 7], which results in areas of increased signal intensity on T2-wighted images (WI) and/or abnormal enhancement on arterial phase, delayed phase, or both. Those areas can present wedge-shaped, peripheral or peribiliary distribution [5].

To the best of our knowledge there is no previous report in the English literature of focal cholangitis manifesting exclusively as liver lesions in asymptomatic patients with history of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). The purpose of this case series is to present six cases of subclinical focal cholangitis manifesting as new hepatic lesions in asymptomatic patients with history of PDAC and biliary tree intervention.

Case presentation

There are six cases with PDAC with new hepatic lesions on computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detected on follow-up (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6): one patient after distal pancreatectomy, one patient after Whipple’s surgery, and four patients after starting chemotherapy for unresectable PDAC. None of the patients had previous liver metastasis or history of hepatic artery procedure. Clinical and imaging features of those patients are summarized in Table 1.

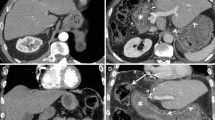

Case 1. a CECT demonstrates an ill-defined hypovascular area in the periphery of segment VII (arrow). Liver biopsy was performed with a diagnosis of inflammatory changes without malignancy. One month after the beginning of antibiotics, (b) CECT shows the resolution of the lesion. (c, d) Liver biopsy demonstrates prominent bile ductular proliferation, active cholangitis and portal oedema, with no malignant neoplasm

Case 2. a CECT shows a hypervascular nodule with target appearance in the periphery of segment VIII (arrow). The patient underwent liver biopsy with a diagnosis of inflammatory changes without malignant cells. b CECT 2 months after antibiotics the lesion was no longer identified. c Liver biopsy demonstrates a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate of hepatic parenchyma with a paucity of bile ductules and no carcinoma is present

Patient demographics and clinical data

Patients ranged in age between 59 and 74 years, with a mean age of 65 years and 4 (67%) were women. Two patients underwent partial pancreatectomy before the detection of the new hepatic lesions (case 2, 235 days of interval; case 4, 479 days of interval). All patients had history of biliary tree intervention, 3 biliodigestive anastomosis, 2 biliary duct stenting, and 1 papillotomy. None of the patients presented clinical symptoms at the time of the diagnosis of the hepatic lesions. Laboratory abnormalities were detected in 2 patients, both had elevated CA 19.9 (74 and 1032 U/mL, normal <37 U/mL) and 1 had elevated alkaline phosphatase (190 U/L, for a normal range of 45–129 U/L). However, these abnormalities did not present a significant increase in relation to previous exams.

Imaging features

Three patients had only contrast-enhanced CT (CECT), one had only MRI and two had both CT and MRI. Overall, seven lesions were identified, five patients presented solitary lesions and one patient had two separate lesions. All lesions presented peripheral distribution, five were hypovascular and two were hypervascular on post-contrast phases. Five lesions were well-defined whereas two were ill-defined. On MRI, all three lesions presented restriction on diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and high signal intensity (SI) on T2WI, and two lesions showed low SI on T1WI. Two nodules demonstrated target appearance on post-contrast images and two lesions presented peripheral transient hepatic attenuation differences. None of the patients had bile ducts changes such as dilatation or thickening.

Outcome

Two patients underwent liver biopsy for further assessment of the new hepatic lesions, which showed inflammatory changes without malignant cells. All patients were treated with antibiotics and underwent imaging follow-up, which demonstrated resolution of the lesions. The mean time interval between the first scan that demonstrated the new hepatic lesions and the follow-up which no longer demonstrated them was 69 days (range, 39–112). None of the patients showed imaging or clinical signs of disease progression during this interval.

Discussion and Conclusions

Infectious cholangitis is a potentially life-threatening condition, usually caused by an obstruction of the biliary tree [8]. Biliary tree intervention is also a relevant risk factor for cholangitis, by allowing microorganisms to ascend from the bowel to the biliary ducts [3]. The main imaging findings of cholangitis are related to bile duct abnormalities, such as dilatation, wall thickening and abnormal enhancement; pneumobilia may also be observed mainly after biliary tree intervention [5]. Nevertheless, liver parenchymal changes can also be demonstrated on imaging, including areas of increased signal intensity on T2WI and/or abnormal enhancement on arterial phase, delayed phase, or both. The treatment of cholangitis is based on antibiotic therapy and biliary drainage with decompression, if biliary obstruction is present [9, 10].

The fact that none of the patients of this case series showed clinical or laboratory signs of infection highlights that cholangitis can be asymptomatic, and imaging features may precede the clinical manifestation [4, 5], mainly in elderly patients [11]. None of the six patients had a significant increase in CA 19.9 levels at the time of diagnosis of the new hepatic lesions. Although, CA 19.9 was elevated in two patients, this raised the suspicion of progression or relapse of PDAC; however, and CA 19.9 increase can also be due to non-oncological causes, such as cholangitis and jaundice [12]. Furthermore, in these two patients that CA 19.9 was elevated, it was lower compared to prior measurement (one patient – case 6 had a significant reduction in compared to the previous exam), which makes the hypothesis of progression of neoplastic disease less likely.

The diagnosis of cholangitis can be challenging given the variability of clinical presentation and imaging findings, which are non-specific [4]. The challenge becomes even greater in clinical scenarios similar to those presented in this case series, in which patients with PDAC presented liver lesions without clinical symptoms or biliary tree abnormalities. The imaging features in our case series of focal cholangitis varied considerably, ranging from a hepatic hypervascular focus to an ill-defined hypovascular area, demonstrating that imaging findings alone cannot establish the final diagnosis. Even using functional imaging technique, such as DWI and PET, there will still be an overlapping between inflammatory and neoplastic changes [13,14,15]. A misdiagnosis of disease progression based solely on new hepatic lesions detected on CT or MRI can result in substantial changes in patients’ treatment, such as change in chemotherapy regimen and changes in eligibility criteria for clinical trials. For that reason, we speculate that in patients with PDAC and history of manipulation of the biliary tree, with no other unequivocal signs of disease progression and no significant rising of CA 19.9, it is reasonable to consider a differential diagnosis of cholangitis before deeming the hepatic lesion as metastasis. In cases where biopsy is not feasible, a therapeutic test and early imaging follow-up should be considered.

To the best of our knowledge there is no previous report in the English literature of focal cholangitis manifesting exclusively as liver parenchymal changes mimicking liver metastasis in patients with PDAC and history of manipulation of the biliary tree. Despite some limitations of this case series, such as the small number of patients and absence of histological confirmation in all cases, this manuscript could help radiologists when reporting similar cases and it could motivate further studies to better assess this entity. In this small group of patients, the diagnostic suspicion of focal cholangitis had a significant impact on clinical management.

Focal cholangitis may occur in asymptomatic patients with history of biliary tree intervention and can mimic hepatic focal lesions, such as metastasis. Radiologists and oncologists need to be aware of the possibility of focal liver parenchymal abnormalities caused by cholangitis, especially in patients with history of biliary tree intervention, because it is not always considered in the differential diagnosis by referring physicians given the lack of symptoms. Correlation with CA 19.9 and clinical status of the patient can help to achieve the correct diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- AP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- BTI:

-

Biliary tree intervention

- CA:

-

Cancer antigen

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced CT

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- BDA:

-

Biliodigestive anastomosis

- DWI:

-

Diffusion weighted imaging

- FU:

-

Follow-up

- HL:

-

Hepatic lesion

- L1:

-

Lesion 1

- L2:

-

Lesion 2

- LB:

-

Liver biopsy

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PDAC:

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- SI:

-

Signal intensity

- THAD:

-

Transient hepatic attenuation differences

- WI:

-

Weighted images

References

Mosler P. Diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:166–72.

van Lent AU, Bartelsman JF, Tytgat GN, Speelman P, Prins JM. Duration of antibiotic therapy for cholangitis after successful endoscopic drainage of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:518–22.

Cammann S, Timrott K, Vonberg RP, Vondran FW, Schrem H, Suerbaum S, Klempnauer J, Bektas H, Kleine M. Cholangitis in the postoperative course after biliodigestive anastomosis. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2016;401:715–24.

Hanau LH, Steigbigel NH. Acute (ascending) cholangitis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2000;14:521–46.

Catalano OA, Sahani DV, Forcione DG, Czermak B, Liu CH, Soricelli A, Arellano RS, Muller PR, Hahn PF. Biliary infections: spectrum of imaging findings and management. Radiographics. 2009;29:2059–80.

Bader TR, Braga L, Beavers KL, Semelka RC. MR imaging findings of infectious cholangitis. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:781–8.

Arai K, Kawai K, Kohda W, Tatsu H, Matsui O, Nakahama T. Dynamic CT of acute cholangitis: early inhomogeneous enhancement of the liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:115–8.

Boey JH, Way LW. Acute cholangitis. Ann Surg. 1980;191:264–70.

Westphal JF, Brogard JM. Biliary tract infections: a guide to drug treatment. Drugs. 1999;57:81–91.

Nagino M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Yamashita Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Wada K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Miura F, et al. Methods and timing of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:68–77.

Rahman SH, Larvin M, McMahon MJ, Thompson D. Clinical presentation and delayed treatment of cholangitis in older people. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2207–10.

Hallemeier CL, Botros M, Corsini MM, Haddock MG, Gunderson LL, Miller RC. Preoperative CA 19-9 level is an important prognostic factor in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with surgical resection and adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2011;34:567–72.

Mannelli L, Nougaret S, Vargas HA, Do RK. Advances in diffusion-weighted imaging. Radiol Clin N Am. 2015;53:569–81.

Mannelli L, Bhargava P, Osman SF, Raz E, Moshiri M, Laffi G, Wilson GJ, Maki JH. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the liver: a comprehensive review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2013;42:77–83.

Krebs S, Monti S, Seshan S, Fox J, Mannelli L. IgG4-related kidney disease in a patient with history of breast cancer: findings on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:e388–9.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

NIH MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concepts EMG, LM, literature search; NH, LM, image review NH, EMG, TJS, LM; clinical information review NH, TJS; pathological review JFH, LHT, CSS; manuscript drafting and edition NH, EMG, TJS, SM, LM, approval of final version of submitted manuscript, all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Horvat, N., Godfrey, E.M., Sadler, T.J. et al. Subclinical focal cholangitis mimicking liver metastasis in asymptomatic patients with history of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and biliary tree intervention. Cancer Imaging 17, 21 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-017-0124-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-017-0124-6