Abstract

Background

The role of upper airways microbiota and its association with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) development in mechanically ventilated (MV) patients is unclear. Taking advantage of data collected in a prospective study aimed to assess the composition and over-time variation of upper airway microbiota in patients MV for non-pulmonary reasons, we describe upper airway microbiota characteristics among VAP and NO-VAP patients.

Methods

Exploratory analysis of data collected in a prospective observational study on patients intubated for non-pulmonary conditions. Microbiota analysis (trough 16S-rRNA gene profiling) was performed on endotracheal aspirates (at intubation, T0, and after 72 h, T3) of patients with VAP (cases cohort) and a subgroup of NO-VAP patients (control cohort, matched according to total intubation time).

Results

Samples from 13 VAP patients and 22 NO-VAP matched controls were analyzed. At intubation (T0), patients with VAP revealed a significantly lower microbial complexity of the microbiota of the upper airways compared to NO-VAP controls (alpha diversity index of 84 ± 37 and 160 ± 102, in VAP and NO_VAP group, respectively, p-value < 0.012). Furthermore, an overall decrease in microbial diversity was observed in both groups at T3 as compared to T0. At T3, a loss of some genera (Prevotella 7, Fusobacterium, Neisseria, Escherichia–Shigella and Haemophilus) was found in VAP patients. In contrast, eight genera belonging to the Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Fusobacteria phyla was predominant in this group. However, it is unclear whether VAP caused dysbiosis or dysbiosis caused VAP.

Conclusions

In a small sample size of intubated patients, microbial diversity at intubation was less in patients with VAP compared to patients without VAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Microbiota is the ecological community of commensal and symbiotic organisms that inhabit a specific body space and interact with local physiological mechanisms [1]. Recent significant advances in respiratory research and the implementation of next-generation sequencing technologies debunked the old dogma of lung sterility [2]. According to experimental models, the gut microbiota can influence the pulmonary microbiota, which confirms the existence of a microbiota gut–lung axis via blood or lymphatic translocation from the altered gut mucosa permeability to the lung [3, 4].

Literature reported an abundance in the lung microbiota composition of Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Fusobacterium and Haemophilus, but this can be highly variable [5].

Physiological homeostasis among commensals residing in the lungs is obtained through a specific and complex mechanism. It has been suggested that the migration of bacteria from the upper respiratory tract is balanced by active microbial elimination, allowing the selection of favorable microorganisms that will indeed constitute the microbiota of healthy lungs [6].

According to studies, a stable commensal ecosystem is a key feature of a healthy microbiota. However, the equilibrium can be distorted by several distinct events defined as perturbations [7], such as pathologies altering natural host defences [8,9,10], infections, diet or drug intake [8, 11]. A specific feature of the microbiota is resilience, defined as the ability of the microbial community to recover its initial function or taxonomical composition following accentuated perturbation [7, 12, 13].

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is one condition that aggressively interferes with physiological lung homeostasis [14]. Recent studies have reported that lung microbiota undergoes a profound reduction in the diversity of species in all MV patients [15,16,17]. To date, most of the studies refer to MV patients as a whole, with no distinction on the reasons that lead to intubation (i.e., pulmonary or non-pulmonary conditions) [17,18,19]. However, this distinction could be important, especially when analyzing the dynamics of pulmonary microbiota and the potential association with MV-related events such as ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

In this study, we performed a pilot analysis of data from a multicenter observational prospective study to assess the composition and over-time variation of upper airway microbiota in patients who underwent MV for non-pulmonary reasons. In particular, we analyzed upper airway microbiota at the beginning of intubation among patients intubated for non-pulmonary reasons and compared microbiota characteristics between patients who had developed VAP in the first week of ventilation and a subgroup of NO-VAP patients matched by total time of intubation. The strong relationship between lung microbiota and VAP was recently described in the study of Fenn et al., in which 55 patients suspected of VAP with a positive culture had increased dysbiosis and genus dominance compared to 55 patients with a negative culture [20].

Taking advantage of data collected in a prospective study (not yet published) aimed to assess composition and over-time variation of the upper airway microbiota in MV for non-pulmonary reasons patients, we conducted an exploratory analysis to describe upper airway microbiota characteristics of VAP and NO-VAP patients.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This exploratory analysis of data was collected in an ongoing multicenter observational prospective study (clinicaltrial.gov NCT 03720093), not yet published. Below, we briefly report the main characteristic of the above study. All consecutive mechanically ventilated patients admitted for non-pulmonary reasons and intubated for at least 48 h were enrolled and followed up to 15 days of intubation. Exclusion criteria were: patients < 18 years old, intubated for respiratory failure due to acute infectious disease (such as pneumonia). The study was approved by the research Ethics Board Brianza (no 2550, 05/07/2017). Informed consent was obtained from patients’ next-of-kin and confirmed by patients later whenever possible. This study was designed to assess the composition and over-time variation of upper airway microbiota in patients on MV for non-pulmonary reasons. Since knowledge of upper airway microbiota is limited and highly heterogenous, we decided to focus on a particular patient population not having an acute pulmonary disease, to reduce potential confounders.

Taking advantage of data collected in this study, we focus the present analysis on characteristics of upper airway microbiota in patients developing VAP, compared to those not developing VAP.

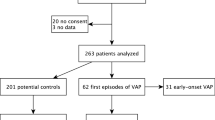

All patients who developed VAP in the first 7 days of intubation were considered in this analysis (cases cohort) and matched with a subgroup of subjects who did not develop VAP (controls cohort) by a ratio of one or, when possible, two per case. Matched controls had a mandatory criterion of comparable MV duration, equal to their matched case or at most 2 days longer, allowing to study the same time points in VAP and matched NO-VAP patients. In the matching process, antibiotic intake in the 48 h before MV was also taken into account when possible. The modified Wald method was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for proportions. The optimal matching algorithm was used to identify the control group that minimizes total intra-pair dissimilarity [21].

The implementation of the algorithm in the 'optmatch' R package was used [22]. Further patient selection details are reported in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Data and sampling collection

All tracheal aspirate samples collected throughout MV according to normal clinical practice were stored for each enrolled patient. In detail, tracheal aspirate collected at intubation (T0) and Day 3 (T3) were analyzed.

After pseudonymization, demographic and clinical information were stored in a web-clinical report form (web-CRF). In addition to ICU admission diagnosis, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), key medical history data, and major events that occurred in the first 15 days of intubation, including VAP, sepsis, and death, were also collected.

Diagnosis of clinical VAP has been considered according to available guidelines [23, 24] as the presence of new signs of respiratory deterioration potentially attributable to infections in association with radiological signs of pneumonia after 48 h of intubation [25]. Microbiological data were collected according to clinical practice (blood culture, microbiological cultures of tracheal aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage). Cases of uncertainty or disagreement were reviewed independently by infectious diseases and intensivist clinicians (LA, FM and EP), and then an agreement was obtained. Sepsis was defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction measured with an increase in the Sequential [Sepsis-related] Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 2 points or more [26].

Tracheal aspirate aliquots were frozen after collection at − 80 °C without any dilution. DNA extraction was performed using QIAmp DNA Blood Kit, Qiagen®, following the user manual guide. In addition to biological samples, we included a commercial bacterial mock community (ZymoBIOMICS® HMW DNA Standard) and negative control in the analysis.

Microbiota analysis by 16S-rRNA gene microbial profiling

Partial 16S-rRNA gene sequences were amplified from extracted DNA using primer pair Probio_Uni and/Probio_Rev, targeting the V3 region of the 16S-rRNA gene sequence [27]. 16S-rRNA gene amplification and amplicon checks were carried out as previously described [27]. 16S-rRNA gene sequencing was performed using a MiSeq (Illumina) according to a previously reported protocol [27]. The.fastq files obtained were processed using a custom script based on the QIIME2 software suite [28, 29]. Quality control retained sequences with a length between 140 and 400 bp and mean sequence quality score > 20, while sequences with homopolymers > 7 bp and mismatched primers were omitted. To calculate downstream diversity measures (alpha and beta diversity indices), 16S-rRNA Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) were defined at 100% sequence homology using DADA2 [30]. ASVs not encompassing at least two sequences of the same sample were removed. All reads were classified to the lowest possible taxonomic rank using QIIME2 [28, 29] and a reference dataset from the SILVA database v. 132 [31]. Biodiversity within a given sample (alpha-diversity) was calculated through richness index (Observed ASVs) calculated for ten sub-samplings of sequenced read pools and represented by box-and-whisker plots. Similarities between samples (beta-diversity) were calculated by Bray–Curtis dissimilarity [32]. The range of similarities is calculated between values 0 and 1. PCoA (Principal Coordinates Analysis) representations of beta-diversity were performed using QIIME2 [28, 29].

Statistical analysis

Clinical data

Categorical variables are presented as frequency and proportion (%), and continuous variables as median and first and last quartiles (Q1–Q3). We used χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests to compare categorical variables and the T-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare continuous variables, depending on variables distribution. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant; SAS 9.4 software (Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Microbiota analysis

Differences in biodiversity between groups were assessed by T-test analysis. Furthermore, PERMANOVA analyses were performed using 1000 permutations to estimate possible significant differences among populations in PCoA analyses. Bacterial differences at the genus level were evaluated through ANOVA and Repeated Measures ANOVA using SPSS software (www.ibm.com/software/it/analytics/spss/). The post hoc analysis Tukey’s HSD (honestly significant difference) test was used for multiple comparisons. MaAsLin2 software [33] was used to determine multivariable association.

Data availability

Raw sequences of 16S rRNA microbial profiling experiments are accessible through SRA study BioProject PRJNA708264.

Results

Between October 2017 and March 2019, 69 patients were enrolled in two Neurological and one general Intensive Care (ICU) Units. Patients’ characteristics are reported in Additional file 1: (Fig. S1 and Table S1). In detail, the median age was 57 years (interquartile range (IQR): 39–71), 30 patients (44%) were females, and 54% were intubated for vascular diagnosis (Additional file 1: Table S2). Eighteen patients (27.5%, 95% CI 17.5–39.6) developed VAP within 15 days from intubation, of which 85% (N = 13) within 7 days.

Microbiota analysis was performed on samples collected from the 13 patients who developed VAP within seven days and 22 matched NO-VAP patients. Clinical characteristics of VAP and NO-VAP patients are shown in Table 1. Moreover, controls samples were selected to balance the frequency of antibiotic administration in the 48 h before the intubation. For this reason, the proportion of samples treated with antibiotics was similar in both groups (54%). Beta lactams/beta lactam inhibitors were the most frequently administered antibiotics. Eleven out of 13 VAP patients have a confirmed microbiological VAP diagnosis (tracheal aspirate positive in 9 cases, and blood cultures positive in 2 cases). In two patients, the microbiological criteria were not fulfilled. However, a review of cases confirms the clinical diagnosis of VAP. The two groups were comparable regarding gender, intubation diagnosis, and surgery at the beginning of intubation. Patients who developed VAP were younger (although only marginally significant, p-value = 0.06) and more frequently diagnosed with sepsis (p-value = 0.02). No marked differences in antibiotic administration and strategies adopted to prevent VAP during the first 72 h of intubation were found between VAP and NO-VAP patients.

Microbiota analysis

The 16S-rRNA microbial profiling analysis generated 2,644,882 sequencing reads with an average of 37,784 ± 13,540 reads per sample (Additional file 1: Table S3). Quality filtering produced a total of 2,303,978 filtered reads with an average of 32,914 ± 11,956 filtered reads per sample (Additional file 1: Table S3). In addition to biological samples, we included a commercial bacterial mock community and negative control in the analysis, to rule out possible technical and methodological contamination. To identify potential differences in the bacterial richness between VAP and NO-VAP samples at different time points, i.e., at T0 and T3, the alpha-diversity analysis based on richness index (Observed Amplicon Sequence Variants, ASVs) was performed. Intriguingly, the biodiversity analysis method allowed to identify six putative outlier samples not included in the 1.5 IQR (Inter-Quartile Range), which showed an Observed ASVs index higher than 380 (Additional file 1: Fig. S2a). These data were also confirmed by calculating the alpha diversity through Chao1 index (Additional file 1: Fig. S2a). Furthermore, the principal coordinates analysis (PCoA analysis) confirmed this hypothesis, revealing a specific cluster composed of the six putative outlier samples (Additional file 1: Fig. S2b). These six samples included both VAP and non-VAP samples at times T0 and T3 and partially represented six different patients. Therefore, we decided to exclude these six samples from our following in silico analysis, obtaining 64 samples. In addition, the PCoA analysis was used to investigate the possible impact of sepsis on microbiota composition (Figure S3), suggesting the absence of a direct relationship between this condition and the upper airway microbiota (PERMANOVA p-value = 0.211). Moreover, we decided to consider the samples at different times as independent to maintain a higher statistical power. In detail, the analysis of the alpha-diversity of selected samples revealed higher biodiversity of the NO-VAP group at T0 (n = 20, richness index 160 ± 102) compared to VAP-subjects at T0 (n = 10, richness index 55 ± 84) (p-value < 0.012) and compared to the VAP (n = 13, richness index 84 ± 54) and NO-VAP (n = 21, richness index 111 ± 72) groups at T3 (p-value 0.006 and p-value 0.043, respectively) (Fig. 1a). However, any differences were found between the VAP and NO-VAP groups at T3. Moreover, the comparison of the alpha diversity between all samples of groups T0 and T3 did not show significant differences (p-value = 0.098). Furthermore, analyses on possible associations between microbial biodiversity and antibiotic therapy, gender, age, and intubation diagnoses showed statistical significance (Additional file 1: Fig. S3b).

Evaluation of alpha- and beta-diversity. a Reports the Whiskers plot representing the richness index (based on the Amplicon Sequence Variants, ASVs) identified from VAP and NO-VAP patients over time (T0, T3). The x-axis represents the different groups, while the y-axis indicates the value of the richness index (observed Amplicon Sequence Variants, ASVs). The boxes are determined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The whiskers are determined by 1.5 of the interquartile range. The line in the boxes represents the median, while the square represents the average. b Reports the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bronchial aspirate samples at T0, subdivided by VAP and NO-VAP. Panel c displays the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bronchial aspirate samples at T3, subdivided by VAP and NO-VAP

The beta-diversity analysis between VAP and NO-VAP groups at each time point suggested a slight difference in microbiota composition of the two groups at T0 (although only borderline significant: PERMANOVA p-value = 0.059), which disappears entirely at T3 (Fig. 1b and c). The evaluation of beta-diversity between all samples of groups T0 and T3 revealed a separate clustering of the two groups (PERMANOVA p-value < 0.05) (Additional file 1: Fig. S3c), although it is difficult to understand if VAP caused dysbiosis or dysbiosis caused VAP.

Evaluation of upper airway microbiota

To evaluate the possible association between bacterial composition and time-point, antibiotic treatment and development of VAP, a multivariate analysis was performed using MaAsLin2 [33]. The analysis revealed a significant negative association of the Streptococcus genus at time-point T3 (p-value < 0.01 and q-value < 0.02), even if there are no particular association with the other parameters included in the analysis. This result, corroborated by the analysis of microbial biodiversity of the samples, seemed to indicate a considerable heterogeneity in microbiota compositions, suggesting the need to analyze the prevalence of each taxon to define the presumed upper airway microbiota. In detail, we considered the samples at different times as independent and we focused on the most prevalent bacterial genera represented by a prevalence > 70% in at least one group (Table 2). Only Streptococcus genus was present with a prevalence of > 70% and an average abundance of > 5% in all groups. Moreover, 5 bacterial genera, i.e., Prevotella 7, Fusobacterium, Neisseria, Escherichia–Shigella and Haemophilus, were identified with a prevalence > 70% and an average abundance > 5% in the VAP T0, NO-VAP T0 and NO-VAP T3 groups (Table 2). On the contrary, the VAP T3 group showed few bacterial taxa with a prevalence > 70%, i.e., Streptococcus and Faecalibacterium genera, confirming a high composition heterogeneity among the group samples.

To identify a specific association between VAP and NO-VAP samples and microbiota composition, we evaluated the trend of each microbial taxon identified with a prevalence > 70% (Table 2). In detail, Actinomyces, Rothia, Granulicatella and Streptococcus genera showed a greater abundance at T0 than T3 in both VAP and NO-VAP groups. Moreover, 6 genera belonging to Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Fusobacteria phyla, i.e., Porphyromonas, Alloprevotella, Prevotella, Prevotella 7, Peptostreptococcus, and Fusobacterium, showed a trend > 70% only in T3 VAP samples (Table 2). Moreover, a specific statistical repeated measures ANOVA analysis was performed to identify significant possible taxonomical differences. In detail, the paired analysis showed that only Prevotella 7 genus revealed a significant p-value (Table 2), presenting a generally higher relative abundance in NO-VAP samples compared to VAP.

Discussion

The longitudinal analysis of upper airways microbiota among intubated patients for non-infectious cause of respiratory failure showed possible differences in diversity between VAP and NO-VAP samples. In detail, the alpha-diversity analysis calculated through the number of identified ASVs revealed that subjects who develop VAP during the first 7 days of intubation have a lower microbiota diversity at T0 than NO-VAP patients. The lower biodiversity of upper airways microbiota at intubation before MV in subjects developing early VAP compared to NO-VAP subjects could allow speculating that low bacterial species richness at the beginning of intubation may represent a predisposing factor to develop ventilator-associated events [34]. In addition, we corroborated the notion that upper airway microbiota undergoes a profound general reduction in species diversity during MV [15, 16, 35], which we noted both in VAP and NO-VAP groups.

The analysis of microbiota composition between samples (beta diversity) revealed a slight borderline significant difference between VAP and NO-VAP patients at T0. These results strengthen the concept of heterogeneity of lung microbiota [5, 9, 36, 37], making it particularly difficult to identify common profiles associated with VAP development, also because it is impossible to ascertain a causal effect of dysbiosis on VAP. However, lower biodiversity and MV-driven dynamism among commensal communities could promote intercurrent infectious events such as VAP.

To define the characteristic upper airway microbiota and its changes during MV, we evaluated the prevalence of each bacteria genera. The analysis over time confirmed the principal role of Streptococcus as commensal bacteria of the respiratory tract microbiota, confirming previous identification of positive association with healthy lungs [38, 39] and possible negative association with the development of lung disease [40]. Furthermore, some genera (Actinomyces, Rothia, Granulicatella and Streptococcus) are more represented during intubation than during ventilation. This finding indicates a possible negative association between these taxa and the duration of mechanical ventilation, allowing us to characterize better the concept of dysbiosis and dynamics of genera representation over time.

Moreover, we found that some genera (Prevotella 7, Fusobacterium, Neisseria, Escherichia–Shigella and Haemophilus) are present both in VAP and NO-VAP patients only at intubation, while after 3 days from the start of MV, they remain only in NO-VAP patients. These findings could suggest that early changes of a putative pulmonary core-microbiota during MV (such as with the loss of specific genera) may predispose to susceptibility to pathogens and pneumonia development. Furthermore, specific statistical repeated measures ANOVA analysis revealed a possible significant correlation between Prevotella 7 genus and NO-VAP condition, confirming the potential role of this bacterial genus in reducing the risk of nosocomial pneumonia [40]. In contrast, some genera (such as Porphyromonas, Alloprevotella, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus and Fusobacterium) seemed to gradually increase their relative abundance in VAP samples. Consequently, they might be considered putative microbial biomarkers of this clinical event. Although Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas are common commensal bacteria of the respiratory tract, several studies reported their involvement in the development of lung disease [39, 40], suggesting a possible role in the establishment and progression of VAP. Interestingly, Prevotella 7 was also more abundant at T3 in VAP samples (trend > 80%), which might appear inconsistent with the above observations. These contrasting results could suggest that development of lung diseases in VAP could be related to multifactorial microbiota factors, such as alpha-diversity and bacterial composition, which are closely related.

Lastly, one of the critical aspects of microbiota analysis is considering the impact of antibiotic treatment on commensal bacteria distribution. Studies on gut microbiota confirmed that antibiotic exposure dramatically interferes with microbiota abundance and diversity [41, 42]; however, the role of antibiotics on upper airways microbiota is under investigation [16]. In our cohort, the proportion of patients with antibiotic administration within the first 72 h from intubation was similar in VAP and NO-VAP patients (about 54%). Thus, a specific multivariate analysis did not highlight the correlation between antibiotic treatment and microbiota composition, suggesting our cohort's lack of marked impact.

This study has limitations that must be addressed. First, the small sample size limits the statistical power and the sample's representativeness concerning this particular population (i.e., patients intubated for non-pulmonary reasons). This is highlighted, for example, if we consider the death proportion, which remains far different than those previously published in similar settings. In a previously published study, Emonet et al. described a mortality of 13.9% among control patients without VAP and 27.8% among VAP patients [35]. The small sample size also prevented a complete ruling out of possible confounders and an exhaustive investigation of any potential role of sepsis, antibiotics and other possible conditions which can influence the microbiota, such as the use of proton pump inhibitors, nutritional therapy, probiotics, vasopressors, opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Large-scale studies are needed to corroborate the results. Second, we did not analyze oral microbiota.

Concerning the association between the gut and upper respiratory tract microbiota, little information is available to date [3, 4] and the mechanism of cross-talking between gut and lung is mostly unknown [43]. The importance of the gut–lung axis is exemplified in patients with chronic gastrointestinal diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), who have a higher prevalence of pulmonary diseases [44]. Only a few studies on gut–lung interaction are available in critical illness setting, demonstrating that the lung microbiome is enriched with gut bacteria both in a murine model of sepsis and in humans with established ARDS [45]. To our knowledge, no data on gut microbiota and VAP have been described.

The absence of oral samples limited us in better understanding whether the commensals found in tracheal aspirate were resident bacteria specific to the upper airway mucosa and/or were oral bacteria inhaled into the lower respiratory tract during intubation. Finally, we focused only on the characteristics of upper airway commensal associated with VAP development. Therefore, further studies are needed to consider the interactions between commensals and mucosal immunity, which plays a crucial role in regulating local homeostasis.

Conclusion

Our analysis confirmed the negative impact of mechanical ventilation on upper airway microbiota biodiversity, highlighting a decrease in bacterial richness during the MV period in both VAP and NO-VAP patients. The collection of further clinical data and their correlation with the composition of the upper airway microbiota could have a significant translational impact in allowing the identification of the underlying clinical or pharmacological baseline components associated with the progression of dysbiosis.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of raw sequences of 16S rRNA microbial profiling experiments is available through the SRA study BioProject PRJNA708264.

Abbreviations

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ASVs:

-

Amplicon Sequence Variants

- PCoA:

-

Principal coordinates analysis

- Web-CRF:

-

Web-clinical report form

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SOFA:

-

Sequential [Sepsis-related] Organ Failure Assessment

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

References

Marchesi JR, Ravel J (2015) The vocabulary of microbiome research: a proposal. Microbiome 3:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-015-0094-5

Charlson ES, Bittinger K, Haas AR et al (2011) Topographical continuity of bacterial populations in the healthy human respiratory tract. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184:957–963. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201104-0655OC

Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DLA et al (2017) Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut–lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.142

Enaud R, Prevel R, Ciarlo E et al (2020) The gut-lung axis in health and respiratory diseases: a place for inter-organ and inter-kingdom crosstalks. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00009

Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB (2016) The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annu Rev Physiol 78:481–504. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105238

Morris A, Beck JM, Schloss PD et al (2013) Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187:1067–1075. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201210-1913OC

Sommer F, Anderson JM, Bharti R et al (2017) The resilience of the intestinal microbiota influences health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:630–638. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.58

Dickson RP, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB (2014) The role of the microbiome in exacerbations of chronic lung diseases. The Lancet 384:691–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61136-3

Bassis CM, Erb-Downward JR, Dickson RP et al (2015) Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. MBio. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00037-15

Caverly LJ, LiPuma JJ (2018) Cystic fibrosis respiratory microbiota: unraveling complexity to inform clinical practice. Expert Rev Respir Med 12:857–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2018.1513331

Wang B, Yao M, Lv L et al (2017) The human microbiota in health and disease. Engineering 3:71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENG.2017.01.008

Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI et al (2012) Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489:220–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11550

Fragiadakis GK, Wastyk HC, Robinson JL et al (2020) Long-term dietary intervention reveals resilience of the gut microbiota despite changes in diet and weight. Am J Clin Nutr 111(6):1127–1136

Yin Y, Hountras P, Wunderink RG (2017) The microbiome in mechanically ventilated patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis 30:208–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000352

Kelly BJ, Imai I, Bittinger K et al (2016) Composition and dynamics of the respiratory tract microbiome in intubated patients. Microbiome 4:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0151-8

Zakharkina T, Martin-Loeches I, Matamoros S et al (2017) The dynamics of the pulmonary microbiome during mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit and the association with occurrence of pneumonia. Thorax 72:803–810. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209158

Dickson RP, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T et al (2020) Lung microbiota predict clinical outcomes in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 201:555–563. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201907-1487OC

Huebinger RM, Smith AD, Zhang Y et al (2018) Variations of the lung microbiome and immune response in mechanically ventilated surgical patients. PLoS ONE 13:e0205788. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205788

Smith AD, Zhang Y, Barber RC et al (2016) Common lung microbiome identified among mechanically ventilated surgical patients. PLoS ONE 11:e0166313. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166313

Fenn D, Abdel-Aziz MI, van Oort PMP et al (2022) Composition and diversity analysis of the lung microbiome in patients with suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care 26:203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04068-z

Hansen BB, Klopfer SO (2006) Optimal full matching and related designs via network flows. J Comput Graph Stat 15:609–627. https://doi.org/10.1198/106186006X137047

Hansen B. B., Fredrickson M., Buckner J., Errickson J., Rauh A. and Solenberger P. (2009) Package “optmatch”: Functions for Optimal Matching.

Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M et al (2016) Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 63:e61–e111. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw353

National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) (2021) Ventilator Associated Event

Papazian L, Klompas M, Luyt C-E (2020) Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 46:888–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05980-0

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW et al (2016) The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287

Milani C, Hevia A, Foroni E et al (2013) Assessing the fecal microbiota: an optimized ion torrent 16S rRNA gene-based analysis protocol. PLoS ONE 8:e68739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068739

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J et al (2010) QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR et al (2019) Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37:852–857. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ et al (2016) DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 13:581–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P et al (2013) The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D590-596. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219

Lozupone C, Knight R (2005) UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8228–8235. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005

Mallick H, Rahnavard A, McIver LJ et al (2021) Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput Biol 17:e1009442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009442

Fernández-Barat L, López-Aladid R, Torres A (2020) Reconsidering ventilator-associated pneumonia from a new dimension of the lung microbiome. EBioMedicine 60:102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102995

Emonet S, Lazarevic V, Leemann Refondini C et al (2019) Identification of respiratory microbiota markers in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 45:1082–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05660-8

Wypych TP, Wickramasinghe LC, Marsland BJ (2019) The influence of the microbiome on respiratory health. Nat Immunol 20:1279–1290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-019-0451-9

Beck JM, Young VB, Huffnagle GB (2012) The microbiome of the lung. Transl Res J Lab Clin Med 160:258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2012.02.005

Clark SE (2020) Commensal bacteria in the upper respiratory tract regulate susceptibility to infection. Curr Opin Immunol 66:42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2020.03.010

Shekhar S, Schenck K, Petersen FC (2017) Exploring host-commensal interactions in the respiratory tract. Front Immunol 8:1971. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01971

Woo S, Park S-Y, Kim Y et al (2020) The dynamics of respiratory microbiota during mechanical ventilation in patients with pneumonia. J Clin Med 9:638. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9030638

Mu C, Zhu W (2019) Antibiotic effects on gut microbiota, metabolism, and beyond. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:9277–9285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-019-10165-x

Sun L, Zhang X, Zhang Y et al (2019) Antibiotic-induced disruption of gut microbiota alters local metabolomes and immune responses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:99. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00099

Tulic MK, Piche T, Verhasselt V (2016) Lung-gut cross-talk: evidence, mechanisms and implications for the mucosal inflammatory diseases. Clin Exp Allergy 46:519–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12723

Keely S, Talley NJ, Hansbro PM (2012) Pulmonary-intestinal cross-talk in mucosal inflammatory disease. Mucosal Immunol 5:7–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2011.55

Dickson RP, Singer BH, Newstead MW et al (2016) Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Microbiol 1:16113. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.113

Acknowledgements

We thank PULMIVAP Study Group Collaborators: Roberta Massafra; Valeria Pastore, Emanuele Palomba (Infectious Diseases Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy); Francesca Elli (NeuroIntensive Care Unit, ASST di Monza, Monza, Italy); Giulia Alessandri, Gabriele Andrea Lugli (Laboratory of Progenomics, Department of Chemistry, Life Sciences and Environmental Sustainability, University of Parma, Parma, Italy); Matteo Filippini, Antonino Panacea, Nicola Latronico, Lorenzo Pilati (Università degli Studi di Brescia; ASST Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy); Italo Calamai, Rosario Spina, Romano Giuntini (Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Unit, AUSL Toscana Centro; S. Giuseppe Hospital, Empoli, Italy); Eleonora Simoncini (Clinical Trials Task Force, Ethics and Care Unit, AUSL Toscana Centro, Piero Palagi Hospital, Florence, Italy); Andrea Forastieri Molinari, Martina Viganò, Cristina Panzeri, Alberto Steffanoni (Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, A. Manzoni Hospital, ASST Lecco, Lecco, Italy); Lara Vegnuti, Sara Donnini, Romilda Tucci, Baldassarre Ferro (Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Spedali Riuniti Livorno ATNO ESTAR, Livorno, Italy); Ilaria Beretta (Infectious diseases Unit, ASST di Monza, Monza, Italy); Riccardo Giudici (Intensive Care, ASST GOM Niguarda, Milan, Italy); Anna Zeduri (School of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy); Marina Munari, Alessandro De Cassai, Federico Geraldini, Marzia Grandis (Anesthesia and Intensive Care Unit, University Hospital of Padova, Padova, Italy); Rosanna Vaschetto, Francesca Grossi, Stefania Guido, Nello De Vita (Ospedale Maggiore della Carità, Novara, Italy); Emanuele Sani (Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Parma, Parma University Hospital, Parma, Italy); Nino Stocchetti, Marco Carbonara, Tommaso Zoerle (Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit, Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy); Antonio Pesenti, Giacomo Grasselli, Chiara Abbruzzese (Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Emergency, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy). We would also like to thank GenProbio srl for the financial support of the Laboratory of Probiogenomics. Part of this research is conducted using the High-Performance Computing (HPC) facility of the University of Parma.

Funding

This work was supported by SITA (Società Italiana Terapia Antimicrobica, https://www.sitaonline.net/2017/11/vincitori-bando-lassegnazione-contributi-ricerca-2017, Prof Andrea Gori) and the Italian Ministry of Health (RF GR-2018-12365988). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of the results, and report writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LA, AM, GC, AB, and AG designed the study and obtained funding. LA, FM and GMM supervised the study conduction. AV was responsible for the conduction of data collection. LM was responsible for all samples preparation and performed 16S-rRNA microbial profiling analysis. EP, SR, TT, SDB and GB collected data. GMM coordinate all samples collection and storage. LC and GN performed the matching algorithm for VAP and NO-VAP patients and the statistical analysis of clinical data collected in the WEB-CRF. FT, CM, LM and MV performed the 16S-rRNA microbial profiling, statistical analysis, and data interpretation. The paper was written by LA, FT, LM and AG and was critically revised by RF, RP, FM, DM, and AB. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board Brianza (no 2550, 05/07/2017). Informed consent was obtained from patients’ next-of-kin and confirmed by patients later whenever possible.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Characteristics of the 69 patients intubated for non-pulmonary conditions included in the main study. Table S2. Distribution of diagnosis at intubation in the 35 patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for non-pulmonary conditions. Table S3. 16S r RNA microbial profiling sequencing reads description. Figure S1. Study flow-chart. Figure S2. Evaluation of outlier samples. Panel a report the Whiskers plot representing the richness index (observed Amplicon Sequence Variants, ASVs, and Chao1 index) identified from VAP and NO-VAP patients. The x-axis represents the different groups, while the y-axis indicates the value of Observed ASVs and Chao1 indexes. The boxes are determined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The whiskers are determined by 1.5 of interquartile range. The line in the boxes represents the median, while the square represents the average. Panel b reports the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bronchial aspirate samples, highlighting the outlier samples in blue. Figure S3. Evaluation of possible impact of the sepsis, antibiotic therapy, gender, age, and diagnoses on upper airway microbiota through beta- and alpha-diversity analyses. Panel a shows the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bronchial aspirate samples at T0 and T3, subdivided according to sepsis condition. Panel b investigates possible correlation between alpha diversity and antibiotic therapy, gender, age and vascular diagnoses at intubation. In detail, the y-axis of the Whiskers plot reports the richness index (based on the Amplicon Sequence Variants, ASVs), while the x-axis represents the different groups. The boxes are determined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The whiskers are determined by 1.5 of the interquartile range. The line in the boxes represents the median, while the square represents the average. Panel c reports the principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bronchial aspirate samples, subdivided by collection time, i.e., T0 and T3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alagna, L., Mancabelli, L., Magni, F. et al. Changes in upper airways microbiota in ventilator-associated pneumonia. ICMx 11, 17 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-023-00496-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-023-00496-5