Abstract

Background

Quantitative lung computed tomography (CT) provides fundamental information about lung aeration in critically ill patients. We tested a scanning protocol combining reduced number of CT slices and tube current, comparing quantitative analysis and radiation exposure to conventional CT.

Methods

In pigs, CT scans were performed during breath hold in a model of lung injury with three different protocols: standard spiral with 180 mAs tube current-time product (Spiral180), sequential with 20-mm distance between slices and either 180 mAs (Sequential180) or 50 mAs (Sequential50). Spiral scans of critically ill patients were collected retrospectively, and subsets of equally spaced slices were extracted. The agreement between CT protocols was assessed with Bland–Altman analysis.

Results

In 12 pigs, there was good concordance between the sequential protocols and the spiral scan (all biases ≤1.9%, agreements ≤±6.5%). In Spiral180, Sequential180 and Sequential50, estimated dose exposure was 2.3 (2.1–2.8), 0.21 (0.19–0.26), and 0.09 (0.07–0.10) mSv, respectively (p < 0.001 compared to Spiral180); number of acquired slices was 244 (227–252), 12 (11–13) and 12 (11–13); acquisition time was 7 (6–7), 23 (21–25) and 24 (22–26) s. In 32 critically ill patients, quantitative analysis extrapolated from 1-mm slices interleaved by 20 mm had a good concordance with the analysis performed on the entire spiral scan (all biases <1%, agreements ≤2.2%).

Conclusions

In animal CT data, combining sequential scan and low tube current did not affect significantly the quantitative analysis, with a radiation exposure reduction of 97%, reaching a dose comparable to chest X-ray, but with longer acquisition time. In human CT data, lung aeration analysis could be extrapolated from a subset of thin equally spaced slices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The quantitative analysis of lung computed tomography (CT) has profoundly changed the understanding of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1–4]. Despite the emergence of bedside tools for the assessment of lung aeration such as lung ultrasound and electric impedance tomography, CT is still the gold standard [5]. In fact, CT is the only imaging technique showing a direct correlation with density [6], from which lung aeration can be inferred with a widely accepted model assuming lung weight as a linear function of Hounsfield units (HU) [7]. Lung aeration compartments can be calculated as percent of the total lung weight, and normal values of healthy adults were recently published [8].

Translation from the research setting to clinical practice of this technique is significantly hampered by practical issues; apart from the need to move the patient from the intensive care unit (ICU) to the CT facility, the necessary high ionizing radiation exposure, and long post-processing segmentation times are important hurdles. To overcome part of these hampering factors, low-dose spiral CT acquisition protocols have been proposed [9, 10]. These methods, while reducing radiation dose, do not reduce the time needed to perform lung segmentation. So far, the only validated means to reduce post-processing time have been visual anatomical estimation of lung aeration [9, 11] or the extrapolation of a reduced subset of ten slices from a whole-chest spiral CT [12–14].

Sequential CT is an acquisition mode in which axial slices are acquired interleaved by an arbitrary distance (feed) along which the patient is not irradiated. Although replaced by spiral volumetric scan modes in most routine CT studies, sequential acquisition is still available in modern scanner because of its superiority in specific indications [15] and has been proposed in lung imaging to reduce dose exposure [16].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the accuracy and feasibility of a lung CT scanning protocol combining the prospective acquisition of a reduced number of thin slices with a reduced tube current, and to estimate the resulting radiation dose and segmentation time reduction. We hypothesized that low-dose sequential CT scan does not result in major loss of information on lung aeration while reducing exposure to radiation compared to conventional CT. For this purpose, we chose a translational study design: in the first part, the method was tested in an animal model of ARDS, and in the second part its robustness was tested in a cohort of critically ill patients.

Methods

In the first part of this investigation, CT scans performed in a porcine model of lung injury (location: university research facility in Dresden, Germany) were analyzed. In the second part, retrospectively collected chest spiral CT scans of patients in the emergency room or the ICU were analyzed (location: university hospital in Genoa, Italy).

Animal study

After premedication with atropine, midazolam and ketamine, 12 pigs were anesthetized with continuous infusion of ketamine, atracurium and midazolam, intubated and mechanically ventilated in volume-controlled mode (VCV) in supine position with tidal volume set at 6 mL/kg (Evita Infinity, Dräger, Germany), under continuous hemodynamic and respiratory monitoring. Experimental ARDS was induced with a previously described double-hit model [17], consisting in warm saline solution lung lavages followed by injurious mechanical ventilation. Twenty-six hours after the induction of ARDS, three CT scans of the whole lung were performed in sequence during respiratory hold: (1) standard spiral scan with 180 mAs tube current-time product (Spiral, 180 mAs); (2) sequential scan with 1-mm slices interleaved by 20 mm feed and 180 mAs (Sequential, 180 mAs); (3) sequential scan with 1-mm slices, 20 mm feed and 50 mAs (Sequential, 50 mAs). The feed of 20 mm was chosen because we expected it to result in a number of about ten slices per scan, as in a previously described method [12, 13]. Respiratory hold was obtained setting the ventilator in continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mode, with the pressure level set equal to the mean airway pressure achieved during VCV; the three scans were interleaved by 1 min of VCV, to avoid desaturation. Images were acquired with a Biograph 16 PET/CT scanner (Siemens, Knoxville, US) with 120 kV tube voltage, collimation 16 × 0.75 mm (spiral scan) or 1 × 1 mm (sequential scans) and dose modulation (CARE Dose4D, Siemens, US); image reconstruction was performed with B70s convolution kernel, 1-mm slice thickness and 0.508 × 0.508 mm2 voxel size. The dose length product (DLP), scan acquisition time and CT dose index (CTDI) were extracted from the structured Digital Imaging and COmmunications in Medicine (DICOM) report, and dose exposure (E) was estimated using a previously published method [18]. At the end of the imaging acquisition, animals were killed with 2 g intravenous thiopental followed by 50 mEq KCl.

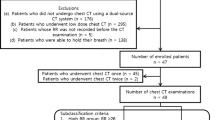

Human study

To verify whether the findings of the animal study could be translated to humans, we retrospectively analyzed chest CT scans of critically ill patients admitted at the emergency department or at the ICU. The CT scanner was a LightSpeed 16 (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, US), tube current was 120 kVp, pitch factor 1.75 and collimation 16 × 0.625 mm. We included only scans of patients aged ≥18 performed with a standard protocol: no contrast medium, 1-mm slice interleave, 1.25 mm thickness and medium-soft convolution kernel. From spiral scans, subsets of images including the entire lung were extracted at increasing distance between slices, mimicking the feed in sequential scans, from 2 to 50 mm in 1-mm steps.

To assess translatability of the results obtained in the animal study, we observed the current-time product used in the clinical practice, the cranio-caudal scan length, and the reliability of the extrapolation from equally spaced 1-mm thin slices, as a proof of the geometric robustness of the extrapolation method to the anatomical differences in chest shape between pigs and humans.

Image analysis

Lung segmentation was performed with ITK-SNAP (http://www.itksnap.org) with a semi-automated algorithm followed by manual refinement, image analysis with custom MATLAB scripts (MathWorks, MA, US). Lung aeration compartments were calculated as percent of the total lung weight using the following Hounsfield unit (HU) thresholds [19]: hyper-aerated (−1000 to −901 HU), normally aerated (−900 to −501 HU), poorly aerated (−500 to −101 HU), non-aerated (−100 to +100 HU). Total lung volume (TLV), weight (TLW) and aeration compartments were extrapolated from each sequential scan in pigs or subset of images in humans, readapting a previously reported formula [20]:

Where N is the number of slices, t is the slice thickness, f the distance between slices (feed) and M i the lung mass in the ith slice (see Fig. 1); the same formula was used for lung volume and aeration compartments.

Outcome measures

The main endpoints were the effective dose (E) reduction and bias between sequential scans and the spiral reference scan. Post-processing workload was estimated as the number of slices that the operator must segment. Safety and feasibility were assessed measuring the scan acquisition time, ensuring that the duration of apnoea was below 40 s, namely the typical duration of a recruitment manoeuvre used in ARDS patients [21].

Analysis plan

In the animal experiment, the Bland–Altman method was applied calculating bias and limits of agreement (LOA) for each variable to assess the agreement with the reference spiral scan. In the human study, data from each subset of images were compared with the entire spiral scan, using the same method. Comparisons of dose measures, number of slices and acquisition time were performed with a Wilcoxon or Friedman test with Dunn’s post hoc, as appropriate. Correlations were sought using Spearman’s ρ. Data are reported as median (interquartile range), where not specified otherwise. Sample size calculation was based on a previously published paper [10] and a pilot scan conducted on a CT dosimetry phantom: we needed to enrol at least four animals to achieve a 95% power to detect a dose reduction of at least 80%. Statistical analysis was performed with R version 3.2.3 (http://www.r-project.org) and significance assumed for p < 0.05.

Results

Animal experiment

Twelve pigs developed lung injury after eight saline lavages and 172 (115–218) min of injurious ventilation; at the time of the CT scan, they were ventilated in VCV mode, with 8.0 (5.0–8.0) cmH2O positive end-expiratory pressure and 0.4 (0.4–0.5) fraction of inspired oxygen, resulting in a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 186.3 (179.5–253.5). The ventilation and gas exchange data refer to the time-point immediately preceding the transfer of the animal to the CT facility, namely 24 h after the induction of lung injury.

The results of the quantitative CT analysis and the Bland–Altman comparisons are reported in Table 1. The use of the dose modulation resulted in measured current-time product values slightly different from the pre-set ones: 169 (164–180), 132 (124–141) and 45 (43–49) mAs, respectively. The cranio-caudal length covered by sequential scans was 240 (220–260) mm.

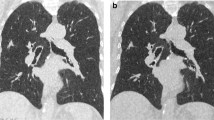

Both types of sequential scans resulted in a lower radiation dose, lower number of acquired slices and longer scan time, as shown in Table 2. Acquisition scan time was ≤33 s in all cases. The sequential scan at 50 mAs resulted in a median effective dose of 0.09, comparable to that of a digital chest X-ray [22]. Figure 2 illustrates axial, coronal and 3D reconstructions of the three acquisition protocols in a representative animal.

Scanning protocols. Axial (upper panels), coronal (middle panels) and 3D reconstructions (lower panels) of the three acquisition protocols in a representative animal. Colors in the 3D reconstruction represent clusters of lung tissue: hyper-aerated (blue), normally aerated (green), poorly aerated (yellow), non-aerated (red)

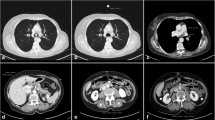

Human study

We collected CT scans from 32 critically ill patients, whose characteristics are reported in the Additional file 1: Supplemental digital content—eTable 1. Most patients (N = 30) were included in another unrelated study concerning the assessment of lung hyperinflation in critically ill patients [23], and the analyses included in this manuscript have not been published before. For each patient, 49 subsets of images at increasing distance between slices were extrapolated and compared with the whole spiral scan, for a total of 1568 comparisons. Bias and LOA worsened at increasing slice interleave (see Additional file 1: Supplemental digital content). The accuracy of extrapolation at 20 mm of distance between slices is shown in Table 3: the number of analyzed slices decreased from 250 (233–278) to 13 (12–14) (p < 0.001). The lung cranio-caudal diameter was 250 (234–276) mm, the number of slices analyzed in the subset with interleave of 20 mm was 12 (12–14), while the current-time product was 229 (201–303) mAs. These three findings were similar to those observed in animal scans, and to the values reported in a study describing the limits of normality of quantitative CT [8].

Figure 3 shows the Bland-Altman comparison for the non-aerated compartment between the experimental protocols and the reference scans in pigs and humans. The Additional file 1 contains extensive details on the analysis results of both human and animal scans.

Discussion

The main findings of our study were that (1) the results of the quantitative aeration analysis performed on the sequential scans had a good agreement with that performed on the whole spiral scan, (2) an approach combining sequential scan and low current-time product results in an effective radiation dose comparable to that of a chest X-ray without affecting significantly the accuracy of the quantitative analysis and (3) this extrapolation method is applicable in CT scans in humans.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, in which lung CT quantitative analysis is extrapolated from a sequential scan with a low current-time product. This combines the advantages of low-dose CT, namely using a lower tube current, with the radiation exposure of only few equally spaced thin chest portions. We achieved a dose reduction around 97%, compared to the 70% described when low tube current alone is applied [9, 10]. The high radiation burden has limited the application of quantitative CT to critically ill patients: for instance, in recent studies in perioperative medicine, ethical concerns have forced researchers to use a single CT slice analysis [24] or magnetic resonance imaging [25]. Using a new approach combining low-dose CT and sequential scans importantly lowers the risk-to-benefit ratio of a quantitative lung aeration assessment to a probably acceptable level.

The method described in this paper is a prospective validation of a modified protocol derived from a previously published work [12–14], in which the authors used a fixed number of ten slices. Translating this in a prospective acquisition protocol would be difficult, as it would require the correction of the distance between slices according to the patient’s lungs’ sagittal diameter. The use of a fixed interleave between slices is easier to implement, as a standard sequential scan with a fixed feed can be used. While not often used in the clinical practice, sequential scan acquisition is available in most modern spiral CT scanners; therefore, this protocol can be easily used in other institutions using different scanners. Overall, there was good agreement between the quantitative analysis performed with the sequential protocols and the spiral scan, with all biases being below 2% for aeration compartments, 10 ml for total volume and 10 g for lung weight.

In the sequential scans, we used thin slices of 1 mm. Slice thickness is a known factor affecting the assessment of aeration compartments, in particular hyper-aerated tissue [23, 26, 27]. There is no unanimous consensus concerning which slice thickness should be preferred for the quantitative analysis of lung aeration [5]: several research groups used 5 mm [8] or 1 mm [17] slices. In spiral scans, thicker slices result in a lower number of images to be segmented to perform analysis, and this might explain why many research groups avoided using thinner slices. Incrementing the slice thickness in sequential scans would result in an increase of dose exposure, therefore jeopardizing the advantages of the sequential scan. Given the lack of a reference standard, we proposed the use of 1-mm slices to prioritize the patients’ dose exposure reduction. However, in specific research settings where other slice thicknesses are warranted, the bias in hyperaeration assessment introduced by the use of thinner slices could be corrected with a recently validated mathematical method [23, 28]. In the studies estimating CT aeration from ten equally spaced slices of 5 to 10 mm thickness, the extrapolation method showed comparable performances in pigs [13], sheep [13], ponies [14] and humans [12]. Based on these previous findings, we hypothesized that extrapolating quantitative analysis from thin 1-mm slices, interleaved by 20 mm, could be used regardless of the discrepancies in lung shape between pigs and humans. Therefore, no changes to the slice sampling protocol were made when switching from the animal study to the human translatability assessment. In this study, the bias and LOA of the extrapolated scans worsened proportionally to the distance between slices, both in pigs and humans: this suggests that the extrapolation method is robust to anatomy variations, as already suggested [12–14]. Dose exposure and number of acquired slices are proportional to the cranio-caudal lung diameter and to the current-time product, which in our study were comparable in pigs and humans

While prospective validation in humans is still warranted to definitively validate this method, the translatability of our findings to humans is supported by the following factors: (1) in humans, the accuracy of the extrapolation from 1-mm slices is excellent; (2) the tube-current product used in the clinical routine in chest spiral CT scans in our institution was comparable to that used in the reference scan of our animal study; (3) the cranio-caudal length covered by a lung CT in humans and pigs is comparable.

Other dose reduction protocols that have been proposed rely only on the reduction of the tube current [9, 10]. The dose reduction that can be achieved with this technique is about 70%, i.e. the patient receives approximately one third of the dose he would have received with a conventional CT. The ultra-low-dose protocol we describe reduces this value to less than one twentieth, approaching the typical effective dose of a digital chest X-ray [22]. Moreover, tube current reduction alone does not reduce the number of slices that the operator has to segment, or visually assess, to perform the image analysis, resulting in a post-processing workload equal to that of a conventional CT.

The main pitfall of using sequential scans is that the acquisition time increases significantly. In our animal study, the sequential CT scan took around 24 s, compared to the 7 s of the spiral scan. Since the best clinical and research practice is to acquire the images during a breath hold, this increase in scanning time could pose challenges in particularly unstable patients, where desaturation is likely to occur. However, all scans were faster than a typical sustained inflation recruitment manoeuvre performed in ARDS patients, which is often performed increasing the airway pressure for 40 s [21]. Nonetheless, newer CT scanners might acquire images even faster.

The present study has several limitations. First, the translatability of our results to human scans was inferred, but not systematically tested: a prospective validation in humans is warranted, as while the reduction of dose exposure should be that observed in pigs, its absolute value might slightly differ. However, the human cohort covered a wide range of lung loss of aeration extension; therefore, the validity of the extrapolation method should not have been affected. Second, the pig scans were performed in breath hold but interleaved by a short period of mechanical ventilation to avoid desaturation, without recruitment manoeuvres between scans: part of the bias between sequential and spiral scans might be explained by this; however, this would result in an over- rather than under-estimation of the bias. Third, human scans were collected retrospectively, with poor control on the acquisition parameters. In particular, intubated patients were scanned during uninterrupted mechanical ventilation and this could have increased motion artefacts. However, since comparisons were made within and not between patients, this should not affect the interpretation of the results of our study. Fourth, human CT scans were previously included in another research and were performed on clinical indication on subjects with either healthy or injured lungs; however, the amount of non-aerated tissue ranged between 1 and 80% therefore can be considered representative of a mixed population of critically ill patients with a broad spectrum of lung conditions. The generalizability of our findings should be tested on a prospective cohort of ARDS patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the combination of low tube current and sequential acquisition of thin slices interleaved by 20 mm provides an acceptable estimate of lung CT quantitative analysis compared to the entire spiral scan, with a notable reduction in dose exposure in pigs. In human CT data, lung aeration analysis could be extrapolated from a subset of thin equally spaced slices, as in the animal study.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTDI:

-

Computed tomography dose index

- DICOM:

-

Digital Imaging and COmmunications in Medicine

- DLP:

-

Dose length product

- HU:

-

Hounsfield units

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LOA:

-

Limits of agreement

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- TLV:

-

Total lung volume

- TLW:

-

Total lung weight

- VCV:

-

Volume-controlled ventilation

References

Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Pelosi P, Goodman LR (2001) What has computed tomography taught us about the acute respiratory distress syndrome? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164:1701–1711. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2103121

Puybasset L, Cluzel P, Chao N et al (1998) A computed tomography scan assessment of regional lung volume in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:1644–1655. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9802003, The CT Scan ARDS Study Group

Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M et al (2006) Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 354:1775–1786. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052052

Gattinoni L, Pelosi P, Pesenti A et al (1991) CT scan in ARDS: clinical and physiopathological insights. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 95:87–94

Ball L, Sutherasan Y, Pelosi P (2013) Monitoring respiration: what the clinician needs to know. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 27:209–223. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2013.06.004

Mull RT (1984) Mass estimates by computed tomography: physical density from CT numbers. AJR Am J Roentgenol 143:1101–1104. doi:10.2214/ajr.143.5.1101

Vieira SR, Puybasset L, Richecoeur J et al (1998) A lung computed tomographic assessment of positive end-expiratory pressure-induced lung overdistension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158:1571–1577. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9802101

Cressoni M, Gallazzi E, Chiurazzi C et al (2013) Limits of normality of quantitative thoracic CT analysis. Crit Care 17:R93. doi:10.1186/cc12738

Chiumello D, Langer T, Vecchi V et al (2014) Low-dose chest computed tomography for quantitative and visual anatomical analysis in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 40:691–699. doi:10.1007/s00134-014-3264-1

Vecchi V, Langer T, Bellomi M et al (2013) Low-dose CT for quantitative analysis in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 17:R183. doi:10.1186/cc12866

Chiumello D, Marino A, Brioni M et al (2013) Visual anatomical lung CT scan assessment of lung recruitability. Intensive Care Med 39:66–73. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2707-9

Reske AW, Reske AP, Gast HA et al (2010) Extrapolation from ten sections can make CT-based quantification of lung aeration more practicable. Intensive Care Med 36:1836–1844. doi:10.1007/s00134-010-2014-2

Reske AW, Rau A, Reske AP et al (2011) Extrapolation in the analysis of lung aeration by computed tomography: a validation study. Crit Care 15:R279. doi:10.1186/cc10563

Reich H, Moens Y, Braun C et al (2014) Validation study of an interpolation method for calculating whole lung volumes and masses from reduced numbers of CT-images in ponies. Vet J 202:603–607. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.10.019

Pace I, Zarb F (2015) A comparison of sequential and spiral scanning techniques in brain CT. Radiol Technol 86:373–378

Bendaoud S, Remy-Jardin M, Wallaert B et al (2011) Sequential versus volumetric computed tomography in the follow-up of chronic bronchopulmonary diseases: comparison of diagnostic information and radiation dose in 63 adults. J Thorac Imaging 26:190–195. doi:10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181f3a30e

Güldner A, Braune A, Ball L, et al (2016) Comparative effects of volutrauma and atelectrauma on lung inflammation in experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001721

Huda W, Magill D, He W (2011) CT effective dose per dose length product using ICRP 103 weighting factors. Med Phys 38:1261–1265. doi:10.1118/1.3544350

Puybasset L, Cluzel P, Gusman P et al (2000) Regional distribution of gas and tissue in acute respiratory distress syndrome. I. Consequences for lung morphology. Intensive Care Med 26:857–869, CT Scan ARDS Study Group

Rylander C, Tylén U, Rossi-Norrlund R et al (2005) Uneven distribution of ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 9:R165–R171. doi:10.1186/cc3058

Grasso S, Mascia L, Del Turco M et al (2002) Effects of recruiting maneuvers in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with protective ventilatory strategy. Anesthesiology 96:795–802

Vodovatov AV, Drozdov AA, Telnova AU, Bernhardsson C (2016) Management of patient doses from digital X-ray chest screening examinations. Radiat Prot Dosim 169:232–239. doi:10.1093/rpd/ncv535

Ball L, Brusasco C, Corradi F et al (2016) Lung hyperaeration assessment by computed tomography: correction of reconstruction-induced bias. BMC Anesthesiol 16:67. doi:10.1186/s12871-016-0232-z

Edmark L, Auner U, Lindbäck J et al (2014) Post-operative atelectasis—a randomised trial investigating a ventilatory strategy and low oxygen fraction during recovery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 58:681–688. doi:10.1111/aas.12322

Spieth PM, Güldner A, Uhlig C et al (2014) Variable versus conventional lung protective mechanical ventilation during open abdominal surgery: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 15:155. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-155

Reske AW, Busse H, Amato MBP et al (2008) Image reconstruction affects computer tomographic assessment of lung hyperinflation. Intensive Care Med 34:2044–2053. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1175-8

Gierada DS, Bierhals AJ, Choong CK et al (2010) Effects of CT section thickness and reconstruction kernel on emphysema quantification relationship to the magnitude of the CT emphysema index. Acad Radiol 17:146–156. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2009.08.007

Bartel ST, Bierhals AJ, Pilgram TK et al (2011) Equating quantitative emphysema measurements on different CT image reconstructions. Med Phys 38:4894–4902

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

The animal study was part of a larger study granted by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant number GA 1256/7-1. The human study was performed with institutional funding only.

Availability of data and materials

Data are retained by the authors as both animal and human scans are also included in two unrelated studies.

Authors’ contributions

LB, PP, FC and MGA designed the study. FC, CB and AG collected the human data. LB analyzed the human data. TK, TB and JK collected the animal data. LB, ABr, ABe and FS analyzed the animal data. LB, PP, ABr, MS and MGA interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All the authors revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Animal Research Ethics Committee (Landesdirektion Sachsen, Germany) approved the animal study on 16 December 2013, protocol no. 24-9168.11-1/2013-53.

The Institutional Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Aziendale–IRCCS AOU San Martino-IST) approved the human study, protocol no. 1458–5/12/2012, and the need for a written informed consent was waived for retrospectively collected scans.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Details on the analysis on pigs and human scans. (PDF 326 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ball, L., Braune, A., Corradi, F. et al. Ultra-low-dose sequential computed tomography for quantitative lung aeration assessment—a translational study. ICMx 5, 19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-017-0133-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-017-0133-6