Abstract

Purpose

Our primary objectives were to (1) describe current approaches for kinetic measurements in individuals following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) and (2) suggest considerations for methodological reporting. Secondarily, we explored the relationship between kinetic measurement system findings and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Methods

We followed the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews and Arksey and O’Malley’s 6-stage framework. Seven electronic databases were systematically searched from inception to June 2020. Original research papers reporting parameters measured by kinetic measurement systems in individuals at least 6-months post primary ACLR were included.

Results

In 158 included studies, 7 kinetic measurement systems (force plates, balance platforms, pressure mats, force-measuring treadmills, Wii balance boards, contact mats connected to jump systems, and single-sensor insoles) were identified 4 main movement categories (landing/jumping, standing balance, gait, and other functional tasks). Substantial heterogeneity was noted in the methods used and outcomes assessed; this review highlighted common methodological reporting gaps for essential items related to movement tasks, kinetic system features, justification and operationalization of selected outcome parameters, participant preparation, and testing protocol details. Accordingly, we suggest considerations for methodological reporting in future research. Only 6 studies included PROMs with inconsistency in the reported parameters and/or PROMs.

Conclusion

Clear and accurate reporting is vital to facilitate cross-study comparisons and improve the clinical application of kinetic measurement systems after ACLR. Based on the current evidence, we suggest methodological considerations to guide reporting in future research. Future studies are needed to examine potential correlations between kinetic parameters and PROMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decision to return to sport (RTS) following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is a complex process [6]. Common criteria used to make this decision include: time from ACLR, functional performance, clinical examination findings, hop tests results, muscular strength, knee range of motion, neuromuscular control, and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [37]. However, the validity of these criteria, when studied individually or combined, has been increasingly questioned [28, 42, 77, 106]. This mandates researchers and clinicians to incorporate objective and accurate biomechanical assessment systems to inform RTS decision-making post-ACLR [48].

Biomechanical assessment systems include kinetic and kinematic measurement systems. These systems can be synchronized with electromyography to examine muscular activity when required [162]. Kinetic and kinematic measurement systems are used to measure force (e.g., force plates) and joint angles (i.e., motion capture systems), respectively. Moreover, these two systems can be used together to measure important kinetic parameters such as joint moments. With the rapid advancement in the field of biomechanics, recent studies are examining the use of different motion capture systems to estimate kinetic parameters such as ground reaction forces and joint moments [74, 75, 132]. However, the methodologies used to estimate joint moments are debatable [29] and kinetic measurement systems are still considered the gold standard when measuring forces [108].

Different kinetic measurement systems have emerged as instruments to objectively assess various functions such as jumping [5, 148], postural control [1, 51], and gait [157]. These systems use force sensors to quantify forces exerted during performance of activities or tasks [32]. They are utilized by clinicians and researchers to assess functional progression throughout rehabilitation and may assist in determining the ability to RTS in post-ACLR individuals [64]. Previous studies have examined various kinetic parameters in the ACLR population; however, there is a lack of consistency in the literature regarding which parameters to assess and what assessment protocol(s) to follow. Thus, the primary objectives of this scoping review were to (1) describe the approaches for kinetic measurements in individuals following primary ACLR and (2) propose methodological reporting considerations for future studies. The secondary objective was to explore how commonly kinetic measurement system findings were related to PROMs. This review will provide clinicians and researchers with further information on the use of kinetic measurement systems in the ACLR population and may also inform future studies which, ultimately, may advance this field of study.

Methods

The current review followed the six-stage methodological framework by Arksey and O’Malley (Table 1) [7] while considering the recommendations by Levac et al. [93], and the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Scoping Reviews [134]. It was conducted and reported according to The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [169]. The current refined review’s protocol was uploaded on the University of Alberta Education and Research Archive: https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-e9fz-et12.

Stage 1: identifying the scope and inquiries

The primary research questions that guided this scoping review were:

What are the current approaches for kinetic measurements in individuals following ACLR?

Is there a need to propose methodological reporting considerations for future studies?

Eligibility criteria

All inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported in Table 2. The constructs of “participants”, “primary ACLR”, and “kinetic measurement systems” are operationalized in Table 3.

Stage 2: identifying data sources and search

Information sources

Potentially relevant studies were identified through literature searches of the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online), EMBASE (Excerpta Medica dataBASE), CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), SPORTDiscus, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global for unpublished theses. These databases were searched since inception with no language limitations.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed by an experienced librarian scientist (LD) with refinement of the search terms through iterative discussions between the study team and research collaborators to ensure identification of relevant records. The search terms included keywords and subject headings (MeSH) that have emerged in this research field, as appropriate. (Supplementary File 1 shows the search strategy.)

Stage 3: record screening and study selection

Potentially relevant records were exported into a reference management software (EndNote X9.3.3) where duplicates were removed [25]. The titles and corresponding abstracts of remaining records were independently screened by 2 raters (WL, MMS) using Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia; available at www.covidence.org). Initially, the 2 raters (WL, MMS) independently screened a random sample of 100 titles and abstracts to assess the appropriateness of the selection criteria and determine the inter-rater agreement between reviewers using a Microsoft® Excel workbook explicitly designed for screening [175]. The raters reached substantial agreement (Cohen Kappa 90% = 0.75; 95% CI 0.60–0.90). The study team further refined the selection criteria prior to commencing full title and abstract screening. Finally, the 2 raters independently performed full-text review to determine final study selection. Disagreement on study eligibility during the title and abstract screening and full-text review stages were resolved through discussion between the two raters; a third rater (MFS) was approached if necessary, until consensus was reached.

Stage 4: data charting

Table 4 outlines the data items extracted from each study. Prior to data extraction, the form was assessed through comparison of data extracted by the 2 raters independently (WL, MMS), using a purposive sample of 10 studies of various designs. Discrepancies in charted data were resolved through discussions between raters.

Stage 5: collate, summarize, analyze and report the results

We conducted a descriptive and numerical analysis of the extracted variables. To align our results with our research questions, we collected the reported objectives and methods for each paper and categorized the outcomes (parameters) based on the movements assessed by the kinetic measurement systems (i.e., jumping, landing, step-over, stop-jump, lunges, cutting movement, squatting, gait, and standing balance). We reported the parameters as defined by the authors of the included studies. We recorded testing protocols, including: the testing environment setup, participants’ preparation, testing conditions, protocol details, number of repetitions, and duration of tasks, as applicable (see Supplementary File 2). We also identified studies that included PROMs and kinetic measurement system parameters. An iterative process was followed to suggest methodological reporting considerations. Specifically, the primary author (WL) drafted methodological reporting considerations based on study findings and team recommendations. Subsequently, the study team met and provided comments and feedback, resulting in the final version of the suggested methodological reporting considerations.

Stage 6: consultation

To employ an integrated knowledge translation and dissemination approach, we engaged a knowledge user (a biomechanist) and a research collaborator (an engineer with expertise in force plates and balance platforms) for their input on the study findings.

Results

Identification of studies

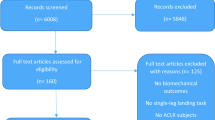

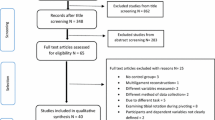

An overview of the study identification process is provided in Fig. 1. Of 5787 identified records, 2027 unique records underwent title/abstract screening, 705 were reviewed in full, and 158 studies were included. Papers evaluating the same cohort with different (a) aims, (b) tasks evaluated, or (c) outcomes were treated independently.

Characteristics of studies

The characteristics of the 158 included studies are summarized in Supplementary File 2. All studies were quantitative including 111 (70.25%) cross-sectional studies, 35 (22.15%) longitudinal, 10 (6.33%) interventional, and 2 (1.27%) case-control studies. Studies were published between 1990 and 2020 with 99 (62.66%) studies published since 2015. Studies were conducted in 28 countries with the highest number conducted in the United States (58 [36.7%]). Overall, 7909 participants were included (female = 2787 [35.2%]; male = 5122 [64.8%]). The mean age of participants ranged from 15.6 (± 1.7) to 48.2 (± 5.5) years. 5570 participants (70.4%) had ACLR, 158 (2.0%) were ACL deficient (ACLD), and 2331 (27.6%) were healthy controls. Participants represented a variety of physical activity and sport participation levels. Healthy control groups existed in 91 (58%) studies.

Movement tasks

We identified 7 different types of kinetic measurement systems that assessed 9 different movements (tasks) in 4 main categories: landing/jumping, standing balance, gait, and other functional tasks. Table 5 contains full descriptions of movements and categories, identified kinetic measurement systems, and frequency of use across the studies. The majority of studies assessed landing, jumping, standing balance, and gait parameters. The force plate was the most commonly used system and the only system with potential to measure all identified movement tasks.

Data was collected and reported, where possible, for the parameters identified, system setup (kinetic measurement system type, sampling frequency), participants’ preparation (warm up, barefoot/shoed, hand position), and protocol details (movement platform, movement direction, movement type, single/double-leg jumping, single/double-leg landing, task after landing, eyes open/closed, single/dual task, number of repetitions). Overall, there was substantial heterogeneity among studies in the parameters examined and the protocols used. Below, we summarize the identified parameters and protocols according to the 4 main movement categories.

Landing/jumping

Sixty-six studies examined landing and/or jumping tasks, with 43 (65.2%) published during the last 5 years. Studies included data from 3307 participants: 981 (29.7%) females, 2326 (70.3%) males; 2170 (65.6%) ACLR, 64 (1.9%) ACLD, and 1073 (32.4%) healthy controls.

Fifty-three unique kinetic variables were identified using 5 different measurement systems (force plates, contact mats connected to jump systems, single-sensor insoles, balance platforms, and pressure mats; Table 5). The following sections describe the parameters identified (as defined and reported by the authors of the included studies) and the measurement protocols used for each measurement system.

Force Plate (Measurement System 1): Force plates were used in 59/66 (89.4%) studies. Of the 59 included studies, 53 (89.8%) assessed landing only [12, 13, 30, 31, 41, 43, 49, 52, 54,55,56, 60,61,62, 68, 76, 79, 80, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90, 102, 103, 107, 110, 115,116,117,118, 120, 127, 129, 142, 146, 149, 150, 153, 156, 158,159,160, 163, 170, 172, 176, 177, 181, 182, 184], 3 studies assessed jumping only [16, 53, 144], and the remaining 3 studies assessed jumping and landing together [83, 114, 122].

Force Plate Parameters: Forty-six unique parameters were identified. Vertical Ground Reaction Force (vGRF) and peak vGRF were the most frequent parameters, each identified in 16 (27.1%) [30, 43, 49, 55, 68, 79, 80, 115, 127, 146, 153, 158, 160, 163, 172] 15 (25.4%) [30, 31, 41, 84, 102, 110, 116, 117, 122, 149, 159, 160, 172, 176, 181, 182] and 15 (25.4%) [30, 31, 41, 84, 102, 110, 116, 117, 122, 149, 159, 160, 172, 176, 181, 182] studies, respectively, followed by the peak Ground Reaction Force (GRF) in 6 (10.2%) studies [52, 62, 110, 118, 122, 184]. The remaining parameters were each measured between 1 to 5 times with a median of 1. (Supplementary File 2-Table 1).

Testing Protocol: This includes system setup, participants’ preparation, and jumping/landing protocol details.

Related to system setup, force plate sampling frequencies were reported in 48 (81.4%) studies and ranged between 50 Hz and 5000 Hz. The most frequently used sampling frequencies were 1000 Hz and 1200 Hz in 17 (28.8%) [16, 52, 53, 68, 76, 79, 80, 83, 120, 142, 144, 146, 150, 158,159,160, 163] and 12 (20.3%) studies [13, 43, 49, 54, 102, 103, 115, 116, 127, 149, 172, 176], respectively.

Regarding participants’ preparation, participants were asked to warm up prior to testing in 18 (30.5%) studies [16, 31, 43, 49, 53, 55, 68, 76, 79, 80, 85, 86, 107, 117, 118, 146, 163, 184]. There was substantial heterogeneity in warm up duration and components across the studies. Participants were barefoot in 5 (8.5%) studies [16, 68, 102, 103, 129], and wore shoes in 20 (33.9%) studies [13, 49, 52, 60, 61, 76, 79, 80, 84,85,86, 88, 89, 120, 146, 149, 159, 176, 177, 181]. The remaining 34 (57.6%) studies did not specify whether participants wore shoes or not [12, 30, 31, 41, 43, 53,54,55,56, 62, 83, 87, 90, 107, 110, 114,115,116,117,118, 122, 127, 142, 144, 150, 153, 156, 158, 160, 163, 170, 172, 181, 184]. Of 22 (37.3%) papers that reported hand placement while testing, 18 studies requested participants to keep hands on hips [16, 41, 49, 53, 56, 68, 76, 79, 83, 88, 89, 120, 129, 142, 144, 172, 181, 182], 2 instructed participants to cross their arms on their chest [43, 60] and 2 studies, by the same author, had participants hold a short rope behind their back [102, 103].

Finally, jumping/landing protocols varied substantially in terms of the jumping platforms, jumping directions, type of jump, number of jumping/landing tasks per study, use of single−/double-leg to jump or land, movement after landing, and number of trials.

Different jumping platforms were used across the included studies. In 37 (62.7%) studies [12, 13, 30, 31, 41, 43, 49, 54,55,56, 60, 62, 68, 76, 79, 80, 87, 90, 107, 115, 116, 127, 129, 146, 149, 150, 153, 156, 158,159,160, 170, 172, 176, 181, 182], participants jumped off a box that ranged in height from 10 to 60 cm, with a median height of 30 cm, onto force plates. The box was placed just behind the force plate in 27 (45.8%) studies [41, 43, 49, 54, 56, 60, 62, 68, 76, 79, 80, 87, 107, 114,115,116, 127, 129, 146, 150, 156, 158,159,160, 170, 181, 182], and at a distance that ranged between 10 cm to 50% of participant’s height in 10 (16.9%) studies [12, 13, 30, 31, 55, 90, 149, 153, 172, 176]. Participants in 21 (35.6%) studies jumped from the floor [12, 13, 30, 31, 53, 55, 83,84,85,86, 88,89,90, 117, 118, 142, 144, 149, 153, 172, 176], and from an inclined surface in 1 study [52]. The horizontal distances between the starting line and the force plates was reported in only 4 (18.2%) studies and varied substantially (100 cm [110], 70 cm [177], 75% of the body height [120], and a predetermined maximum distance [61]).

Likewise, different jumping directions were reported across the studies. Participants dropped/stepped down off a box onto a force plate in 25 (42.4%) studies [41, 43, 49, 54, 56, 60, 62, 68, 76, 79, 80, 87, 107, 114,115,116, 127, 129, 146, 150, 156, 158,159,160, 170], jumped forward off a box onto a force plate in 10 (16.9%) studies [12, 13, 30, 31, 55, 90, 149, 153, 172, 176], jumped forward from the floor in 7 (16.9%) studies [16, 61, 69, 110, 120, 122, 184], jumped to the side in 3 (5.1%) studies [102, 103, 163], and jumped vertically from the floor, from a box, and from an inclined surface in 11 (18.6%) [53, 83,84,85,86, 88, 89, 117, 118, 142, 144], 2 (3.4%) [181, 182], and 1 (1.7%) study [52], respectively.

While most studies (n = 43 [72.9%]) assessed only 1 jumping/landing task [12, 13, 16, 30, 41, 43, 49, 53,54,55,56, 60,61,62, 68, 76, 83, 87,88,89,90, 102, 103, 107, 110, 115,116,117, 120, 127, 142, 144, 149, 153, 158,159,160, 170, 172, 176, 177, 181, 184], 12 (20.3%) studies assessed 2 tasks [31, 84,85,86, 114, 118, 122, 129, 150, 156, 163, 182], 1 (1.7%) study assessed 3 tasks [146], and 3 (5.1%) studies assessed 4 tasks [52, 79, 80].

Of the studies that reported on jump type, 8 studies requested participants to perform counter movement jumps (CMJ) [24, 83, 88, 89, 117, 118, 142, 144], 3 required participants to perform squat jumps [16, 52, 53], 1 study reported vertical jumps while not allowing for countermovement [86], and 3 studies requested participants to do lateral jumps over hurdles of different heights (15 to 24 cm) and then rebound [102, 103, 163]. Of those studies that performed a drop landing, only 2 studies instructed participants to land on their toes [49, 107].

In studies reporting landing on 2 legs (n = 32 [54.2%]), participants took-off from double- and single-leg stances in 27 studies [12, 30, 31, 43, 49, 52, 54, 55, 62, 68, 83,84,85,86, 88,89,90, 107, 110, 114, 116, 127, 144, 146, 149, 150, 176] and 3 studies [158,159,160], respectively. The remaining 2 studies did not report on the take-off stance position [79, 80]. When landing on a single leg (n = 25 [42.4%]), 18 studies reported jumping from a single-leg stance position [16, 41, 53, 56, 61, 76, 102, 103, 115, 120, 122, 142, 156, 163, 170, 181, 182, 184], 6 studies reported jumping from a double-leg stance position [60, 117, 118, 129, 172, 177], while 1 study did not report the starting position [153]. After landing, activities varied across studies according to the landing strategy (i.e., single- vs. double-leg landing). Maintaining balance was most commonly reported after landing on a single leg (10/25 studies [40.0%]) [87, 102, 103, 129, 142, 156, 177, 181, 182, 184] while maximum vertical jump was the most reported activity performed after landing on both legs (19/32 [59.4%]) [12, 30, 31, 54, 55, 62, 68, 79, 88, 89, 114, 116, 127, 149, 158,159,160, 170, 176]. Other activities such as “cut and run” [110] or “pivot and run” [90] were each reported once, following participants’ landing on both legs. Repetitions/trials were completed between 1 and 10 times across studies, with a median of 3 trials per study. (Supplementary File 2-Table 1).

Balance Platforms (Measurement System 2): One study assessed jumping using a balance platform to identify the number of jumps and the peak and minimum values of GRF [39]. Jumping was performed on a single leg with no information given on testing conditions. (Supplementary File 2-Table 1).

Pressure Mats (Measurement System 3): One study used pressure mats to assess peak load and flight time during jumping. Participants were requested to jump barefoot on single and double legs [40]. No further information was provided regarding warm up or testing conditions. (Supplementary File 2-Table 1).

Contact Mats and Jump Systems (Measurement System 4): Three studies reported on contact mats synchronized with jump systems (i.e., computer software or device) to assess jumping [24, 125, 135]. Jump height [24, 135], total power [24], relative power [24], and limb symmetry index [125] were the 4 unique parameters identified.

Several protocol items were inconsistent across 2 studies [24, 135], while 1 study did not provide protocol information [125]. Two studies did not report whether participants warmed up or not, were shoed or barefoot, nor did they discuss hand placement. One study described the jumping activity as 3 consecutive double-leg CMJs with the aid of the arms with a 10-s break between trials [24]. The other study had participants perform 3 10-s jumping trials (for maximum number and height possible) while keeping hands on hips [135]. The best trials were used for analysis in both studies. (Supplementary File 2-Table 1).

Single-Sensor Insoles (Measurement System 5): Two recent studies using the same cohort of individuals with ACLR and healthy controls reported on single-sensor insoles to assess landing [130, 131], using the same variables and protocols to address different aims. One evaluation compared knee bracing and no bracing conditions during landing [130], while the other compared hop distance and loading symmetry [131]. Participants were requested to hop as far as possible taking off and landing on 1 leg (single hop), to hop 3 consecutive times (triple hop), and to hop 3 consecutive times while laterally crossing over a 6-in.-wide strip with each hop and progressing forward. Each test was repeated twice [130, 131]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 1).

Standing balance

We identified 57 studies examining standing balance published between 1994 and 2020, with 28 (49.1%) papers published since 2015. These studies included 3173 participants; 1206 (38.0%) females, 1967 (62.0%) males; 2148 (67.7%) ACLR, 103 (3.2%) ACLD, and 922 (29.1%) healthy controls.

Forty-eight balance parameters were identified using 4 different kinetic systems (force plates, balance platforms, Wii balance boards, and pressure mats). Each protocol described the kinetic measurement systems used, participant preparation (barefoot or shoed), standing position (single−/double-leg stance, hand placement, looking at a target (yes/no)) and testing conditions (eyes open/closed, single/dual tasks, static/dynamic task).

Force Plate (Measurement System 1): Of 57 studies assessing standing balance, 23 (40.3%) used force plates [1, 14, 21,22,23, 26, 45,46,47, 51, 55, 56, 59, 64,65,66,67, 87, 123, 136, 165, 166, 187]. Center of pressure (CoP) velocity was the most commonly measured parameter (n = 10 [43.4%]) [1, 21, 22, 26, 45, 51, 55, 59, 123, 187]. CoP displacement in anterior-posterior and medio-lateral directions [1, 14, 22, 23, 51, 123], and CoP length of path [14, 67, 87, 136, 165, 166] were the second most frequently used parameters, where each was measured in 6/23 (26.1%) studies. The CoP sway area was measured in 5/23 (21.7%) studies [1, 45, 51, 59, 136]. The remaining parameters were each used in 1 to 2 of the 23 studies. (Supplementary File 2-Table 2).

Testing Protocol: This includes system setup, participants’ preparation and balance testing protocol details. Protocols for measuring standing balance using force plates demonstrated limited consistency across studies and lack of reporting for important items. The following sections discuss consistency or lack thereof in protocol reporting.

System setup varied among studies assessing balance using force plates. While most studies reported asking participants to stand directly on the force plate, 1 study placed foam [14] and another placed a wobble board on top of the force plate [1]. Force plates were sampled at frequencies ranging from 40 Hz to 2000 Hz, with a median of 100 Hz. Three studies did not report the frequency used [59, 66, 187].

Likewise, participants’ preparation varied amongst studies and lacked detailed reporting. Warm-up sessions were reported in 6 (26.1%) studies [45, 55, 64, 65, 67, 187]. Participants were requested to be barefoot in 10 (43.5%) studies [23, 46, 47, 51, 55, 123, 136, 165, 166, 187], shoed in 1 (4.3%) study [65], while the remaining 12 (52.2%) studies did not report this detail [1, 14, 21, 22, 26, 45, 56, 59, 64, 66, 67, 87]. Hand placement was also inconsistent; hands were placed on the hips in 7 (30.4%) studies [45, 55, 56, 64,65,66,67], crossed on the chest in 6 (26.1%) [22, 23, 26, 59, 165, 166], placed free at the side of the body in 5 (21.7%) [46, 47, 51, 187], and not reported in the remaining 5 (21.7%) studies [1, 14, 21, 87, 123].

Finally, balance testing protocols were heterogeneous in terms of testing conditions (single−/double-leg stance, focusing on a target or not, eyes open/closed, single/dual tasks). Standing balance was assessed under both single- and double-leg stance in 5 (21.7%) studies [22, 23, 46, 47, 51] and in double-leg stance in 3 (13.0%) studies [1, 136, 165]. The remaining 15 (65.2%) studies assessed single-leg standing balance only [14, 21, 26, 45, 55, 56, 59, 64,65,66,67, 87, 123, 166, 187]. Participants were asked to look at a target in 7 (30.4%) studies [1, 51, 56, 64, 67, 123, 166]. In 6 (26.1%) studies, balance was tested in eyes open and closed conditions [14, 26, 66, 123, 136, 187], while 5 (21.7%) studies assessed balance under eyes closed conditions only [22, 23, 45, 55, 59, 165], and the remaining 11 (47.8%) studies had the participants’ eyes open. Most studies (22/23 (95.6%)) assessed balance using a single task [1, 14, 21,22,23, 26, 45,46,47, 51, 55, 56, 59, 64,65,66,67, 87, 123, 136, 165, 166, 187]; only 1 study used dual tasks (a concurrent physical and cognitive task) [1]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 2).

Balance Platforms (Measurement System 2): Balance platforms were used in 28 studies [2,3,4, 10, 11, 44, 57, 63, 73, 81, 92, 95, 105, 111, 112, 119, 121, 124, 126, 128, 140, 141, 147, 161, 171, 173, 185, 186]. Stability index was the most widely used parameter, reported in 12 (42.9%) studies [10, 11, 92, 95, 105, 111, 112, 124, 140, 173, 185, 186], followed by anterio-posterior and medio-lateral stability indices, reported in 9 (32.1%) studies [3, 10, 105, 111, 112, 124, 140, 173, 185]. The remaining parameters were reported only 1 to 4 times across all studies. (Supplementary File 2-Table 2).

The testing protocols for balance platforms were described in all but one study [186]. In general, most protocols included information on participants’ preparation, and the testing protocol used. However, many studies did not report important protocol items.

With regard to participants’ preparation, participants had warm-up sessions in 3 (10.7%) studies [73, 105, 185]. They were requested to participate barefoot in 11 (39.3%) studies [2, 3, 10, 57, 92, 95, 111, 112, 121, 124, 126] and remain shoed in 1 study [128]. The remaining 16 (69.6%) did not specify whether participants were barefoot or not. Further, of 13 (46.4%) papers reporting hand position, 7 studies requested participants to cross arms on chest [3, 63, 73, 119, 128, 140, 171], 4 placed hands on hips [92, 95, 111, 112] and 2 studies reported participants’ hands hanging by their sides [10, 57].

The testing conditions and protocols details were heterogeneous and lacked sufficient reporting when assessing standing balance using balance platforms systems. The majority of papers (n = 17 [67.9%]) reported assessing single-leg standing balance [2, 3, 63, 73, 81, 92, 95, 111, 112, 119, 121, 124, 126, 128, 140, 161, 185], while 5 (17.9%) assessed balance in double-leg stance [4, 11, 57, 141, 173] and 5 (10.7%) reported investigating balance in both conditions [10, 44, 105, 147, 171]. Only 6 (21.4%) studies compared standing balance under eyes open and closed conditions [2, 63, 81, 111, 112, 126], while 11 (47.8%) papers had participants focusing on targets while attempting to maintain balance [3, 63, 73, 95, 105, 111, 112, 126, 161, 171, 173]. Most studies (n = 20 (71.4%)) assessed either static (n = 9 (32.1%)) [2, 63, 73, 95, 121, 126, 140, 141, 161], or dynamic balance (n = 11 (39.3%)) [3, 4, 10, 92, 105, 111, 112, 119, 124, 128, 173], while 7 (25.0%) studies compared both conditions [11, 44, 57, 81, 147, 171, 185]. Only 1 study added a cognitive task while participants were trying to maintain balance [2]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 2).

Wii Balance Boards (Measurement System 3): Wii balance boards were utilized to assess standing balance in 4 (7.0%) studies published between 2013 and 2017, reporting 8 different parameters [34, 35, 38, 70]. CoP displacement in anterior-posterior and medio-lateral directions [34, 38], CoP length of path [34, 70], CoP velocity [35, 38] and standard deviation [35, 38] were each calculated in 2 (50%) studies. Other parameters such as CoP amplitude [35], CoP fast/slow sway [34], discrete wavelet transform and sample entropy of the CoP trace [35], were each calculated once across studies. (Supplementary File 2-Table 2).

There was reasonable consistency among the 4 reported testing protocols. Participants were barefoot in all studies. Hands were placed on hips in 2 studies [35, 70], crossed on chest in 1 study [38], and not reported in the remaining study [34]. In 1 (25.0%) study, participants were asked to move their arms to measure balance under a dual task condition [70]. All participants had their eyes open; however, in 2 studies, they were instructed to look forward at a target [35, 70]. Three studies [35, 38, 70] investigated single-leg balance and 1 study assessed double-leg balance [34].

Pressure Mats (Measurement System 4): Pressure mats were used by only 2 (3.5%) studies to assess standing balance [33, 82]. Five parameters were identified including ellipse area [33, 82], CoP standard deviation in anterior-posterior and medio-lateral directions, CoP path length, CoP velocity, and sway area [82].

While participants in 1 study were barefoot [82], the other study did not report whether they were shoed or not [33]. Likewise, 1 study reported the arms being free at participants’ sides [33], while the other didn’t specify [82]. Participants in both studies were asked to look forward during testing; however, 1 study also assessed balance under an eyes-closed condition [33]. Both studies investigated balance in both single- and double-leg stances. (Supplementary File 2-Table 2).

Gait

Thirty-three studies examining gait were published between 1997 and 2020 with 27 (81.1%) published since 2015. They represented data from 1261 participants: 708 (56.1%) males, 553 (43.9%) females, 1059 (84.0%) ACLR, 10 (0.8%) ACLD, and 192 (15.2%) healthy controls.

Forty-four unique variables were identified to assess gait using 3 different systems (force plates, force-measuring treadmills, and pressure mats; Table 5). The following section discusses the parameters identified, and the measurement protocols used for each of those systems including, where applicable; system setup (sampling frequency), participants’ preparation (barefoot/shoed) and protocol details (self-selected/predetermined speed, single/dual task, testing condition, distance and duration). (Supplementary File 2-Table 3).

Force Plates (Measurement System 1): Force plates were used in 26 (78.8%) studies. Overall, there was a lack of consistency in the measured parameters across studies using force plates to assess gait. Important protocol items such as gait speed and shoe wear conditions were reported in 20/26 (70%) [17, 19, 20, 27, 72, 99, 101, 109, 114, 133, 137,138,139, 154, 155, 159, 168, 179, 180, 183], and 14/26 (53.8%) [17, 18, 72, 99, 109, 133, 137,138,139, 150, 159, 164, 179, 180], respectively.

Force Plates Parameters in Gait Assessments: Thirty-six parameters were identified in the 26 studies that assessed gait using force plates. Peak vGRF was the most frequently measured variable in 8 (30.8%) studies [18,19,20, 72, 138, 139, 159, 168], followed by vGRF, which was measured in 6 (23.1%) studies [109, 154, 164, 179, 180, 183]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 3).

Gait Testing Protocol: This includes force plate system setup, participants’ preparation, as well as the gait testing protocols using force plates. Regarding system setup, the sampling frequency was reported in 22 (84.6%) of 26 studies [9, 17,18,19,20, 27, 36, 72, 94, 99, 101, 133, 138, 139, 149, 150, 154, 155, 159, 164, 168, 183]. Sampling frequency ranged between 400 Hz and 1200 Hz with a median of 1080 Hz. The most commonly reported frequencies were 1200 Hz and 1000 Hz in 9 [17,18,19,20, 72, 94, 99, 138, 149] and 5 studies [9, 139, 150, 159, 168], respectively.

Related to participants’ preparation, only 2 studies reported asking participants to warm-up prior to testing [94, 101], and only half of the studies reported whether their participants were shoed (n = 3) [133, 159, 164] or not (n = 10) [17, 72, 99, 109, 138, 139, 149, 150, 179, 180].

Different testing conditions and protocols were followed across the studies. Most studies assessed only walking gait (n = 21 (80.8%)) [9, 17,18,19,20, 36, 72, 99, 101, 138, 139, 149, 150, 154, 155, 159, 168, 179, 180, 183], while 2 (7.7%) studies assessed only running gait [133, 164], and 3 (11.5%) studies assessed both walking and running gaits [94, 109, 114]. Of 21 (80.8%) studies that reported speed, 16 (76.2%) reported that participants walked at a self-selected speed [17, 19, 20, 27, 36, 72, 101, 109, 133, 138, 139, 149, 154, 179, 180, 183], while 4 (19.0%) studies used a pre-determined speed [99, 155, 159, 168], and 1 (4.8%) study indicated testing participants in both conditions [114]. No study tested gait in a dual task condition. Participants in 5 (19.2%) studies were asked to look forward at a target [36, 99, 133, 138, 139]. Walking distance greatly varied in the 6 (23.1%) studies, with reported distances ranging from 3 to 20 m (median = 6.5 m) [17, 18, 27, 101, 138, 139]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 3).

Force-Measuring Treadmills (Measurement System 2): Six studies used force-measuring treadmills in gait assessment and reported 8 parameters including vGRF [50, 58, 98], vGRF limb symmetry index [98], peak vGRF [96, 97], peak vGRF normalized to body weight [113], instantaneous vGRF loading rate [96, 98], instantaneous vGRF loading rate normalized to body weight [97] instantaneous vGRF loading rate limb symmetry index [97], and root mean square error between actual vGRF and biofeedback target vGRF [96].

Testing protocols and reporting standards varied among the studies measuring gait using force-measuring treadmills. Only 1 study reported a warm-up session prior to testing [58]. Two studies reported that participants had their shoes on during testing [58, 113] while the remaining studies did not specify [50, 96,97,98]. While 4 studies examined walking at a predetermined speed [50, 96,97,98], 1 study assessed walking and running at a predetermined speed [113], and 1 study assessed running at a self-selected running speed [58]. Only 1 study assessed gait with and without real time biofeedback about participants’ GRF (as a dual task and a single task) [96]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 3).

Pressure Mats (Measurement System 3): One study used a pressure mat with a sampling frequency of 150 Hz to identify spatiotemporal parameters including velocity, cadence, step length and width. Participants walked at both self-selected normal and fast speeds for 8.5 m. It was not specified whether participants were shoed or barefoot [8]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 3).

Other functional movements

In addition to the aforementioned movement tasks, our review identified papers assessing other functional movements including; cutting movements, squatting, stop-jumps, step-overs, and lunges.

First, cutting movements: Eight studies used force plates to assess cutting movements (change in direction) kinetics. They were published between 2011 and 2020, with 6 (75%) papers published in the last 5 years. The studies represented data from 536 participants: 404 (75.4%) male, 132 (24.6%) female; 386 (72.0%) ACLR, 10 (1.9%) ACLD, and 140 (26.1%) healthy controls.

Nine different parameters were identified, mostly related to GRF. Identified parameters included GRF [78, 94], time to peak GRF [15, 110], peak vGRF [30, 31, 110], peak vGRF normalized to body weight [110], vGRF loading rate [30], vGRF normalized to body weight (in vertical, medial and posterior directions) [80], and Lyapunov exponent [91]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 4).

Testing protocol items: Sampling frequencies used were heterogeneous, ranging between 1000 Hz to 5000 Hz with a median of 1200 Hz. Protocols were also heterogeneous with several studies not reporting on important protocol items. For example, of 8 studies, only 5 (62.5%) reported having participants warm-up prior to testing [30, 31, 78, 80, 94], and only 3 (37.5%) reported that participants wore shoes [15, 78, 80]. The movements or conditions preceding the cutting movement (jumping over a hurdle [30, 31], standing [78], and landing after jumping [110]) were only reported in 4 studies, 2 of which were by the same author and included the same cohort [30, 31]. The cutting movement direction was planned in 3 (37.5%) studies [30, 31, 94], not planned in 1 (12.5%) study [110], while 2 (25%) studies (by the same author) tested cutting movements in both planned and unplanned conditions [78, 80]. One study investigated the effect of vision on participants’ performance by testing them under both full and disturbed vision conditions [15]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 4).

Second, squatting: Eight variables were identified in 6 studies that assessed squatting, utilizing 2 kinetic measurement systems; force plates were used in 5 (83.3%) studies [150,151,152,153, 178], and a pressure mat was used in the remaining study [40]. These papers were published between 2003 and 2020, with 4 [66.7%] published since 2015. The studies represented data from 207 participants (63 [30.4%] female, 144 [69.6%] male; 142 [68.6%] ACLR, 65 [31.4%] healthy controls).

Force plates (Measurement System 1) were used in 5 (83.3%) studies [150,151,152,153, 178]. Six different parameters were identified across studies including: first vertical maximum [150], peak vGRF [151], anterior-posterior GRF [152], medio-lateral GRF [152], vGRF [152, 153, 178], and weight bearing symmetry [178].

Squatting testing protocol: Overall, protocols of measuring squatting kinetics using force plates were heterogeneous and lacked sufficient reporting. Among the 5 studies using force plates, 2 reported the sampling frequency as 1000 Hz [150, 152], 2 did not report [153, 178], and 1 reported a sampling frequency of 600 Hz [151]. Only 1 study reported asking participants to warm up for 5 min on a stationary bike [151], and only 1 study reported that participants were barefoot [152]. Squatting speed was predetermined in 2 studies [150, 178], self-selected in 2 studies [151, 152], and not reported in the remaining study [153]. Participants squatted with both legs in 4 (80.0%) studies [150,151,152, 178], and with a single leg in 1 (20%) study [153]. The terminal squatting position was consistent across 3 studies, where participants were asked to descend until the posterior thigh was parallel to the floor [150, 151, 178]. In the remaining 2 studies, participants were asked to squat to a comfortable position while keeping the torso upright [152], or to squat as deep as possible [153]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 5).

Pressure Mats (Measurement System 2): One study used pressure mats to assess double- and single-leg squatting in barefoot participants [40]. The study did not report on the squat speed or the terminal squatting position. The pressure mat measured peak load while squatting. (Supplementary File 2-Table 5).

Third, stop-jump: Of the 158 studies, only 2 assessed a stop-jump task [143, 145]. The 2 papers represented data from 67 participants; 32 (47.8%) females, 35 (52.2%) males; 45 (67.2%) ACLR, and 22 (32.8%) healthy controls. The 2 papers reported using force plates to assess stop-jumps. Nine different parameters were identified including peak vGRF ratio index, peak vGRF gait asymmetry index, peak vGRF symmetry index, peak vGRF symmetry angle, peak vGRF normalized symmetry index [143], peak vGRF, peak posterior vGRF, loading rate, and impulse [145].

For the stop-jump task, there were several similarities in the study testing protocol details. In addition to using the same sampling frequency of 2400 Hz, participants in both studies were asked to approach the force plate as quickly as possible, stop, then jump as high as possible. No information was given about landing. Neither studies reported whether participants had a warm-up, or whether they had their shoes on or were barefoot [143, 145]. One study reported having participants jump off one foot, land on two, and perform a subsequent 2-footed jump [145]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 6).

Finally, step-over and lunges were both reported in only 1 paper which included 36 participants; 13 (36.1%) female, 23 (63.9%) male; 18 (50%) ACLR, and 18 (50%) healthy controls [104]. The study used a force plate for kinetic measurements. Three unique parameters were identified while performing the step-over task, including the lift up index, movement time, and impact index. In addition, the study reported 4 other parameters while performing lunge tasks including lunge distance, contact time, impact index, and force impulse [104].

For the step-over task, with shoes on, individuals were asked to perform a 5-min treadmill warm-up and then to step up onto a 30 cm box while the lagging leg was carried up and over to land on the opposite side of the starting position. For the lunge task, participants were requested to lunge forward with one leg on a long force plate and then return to the original standing position [104]. (Supplementary File 2-Table 6).

Kinetic measurement systems and PROMs

Of 158 studies, only 6 studies reported on both kinetic measurement system findings and PROMs [9, 92, 98, 117, 158, 161]. The earliest study was published in 1996 and evaluated the association between standing balance and PROMs (Cincinnati Scale and satisfaction score) [161]. The remaining 5 studies were published in 2018 [9, 98], 2019 [92, 158] and 2020 [117]. There was inconsistency in the reported parameters and/or PROMs across these 6 studies (Table 6).

Methodological reporting considerations

Based on the substantial heterogeneity seen across studies in the methodological details and outcomes reported, we created a table of methodological reporting considerations for researchers designing studies using kinetic measurement systems (Table 7). The goal of this information is to improve standardized reporting of methodological approaches and kinetic measurements, which should facilitate cross-study comparisons to advance this burgeoning field of research and improve the clinical application of findings. We developed these methodological reporting considerations as they relate to the movement tasks, kinetic system features and selected outcome parameters, participant preparation, and protocol details.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this scoping review was to describe the approaches for kinetic measurements in individuals following ACLR. While force platforms can be used in conjunction with motion capture systems to measure kinetic variables such as joint moments, the intent of the study was to describe approaches and parameters using kinetic measurement systems only. Results of our evaluation demonstrate a substantial increase in the evaluation of kinetic measures in this patient group in recent years. Further, we noted marked heterogeneity in parameters evaluated and protocols followed, in addition to inconsistencies in reporting. In this review, we highlighted the current gaps in reporting and have generated a table of suggested methodological considerations to facilitate improved reporting when using kinetic measurement systems in the post-ACLR population.

In 1976, the first commercially available force plate was constructed to be used for gait analysis [71]. Technology advancements in recent years have facilitated kinetic assessments allowing more extensive measurement of movements/tasks. While the earliest included paper in this review was published in 1990, more than 66% of the included studies were published since 2015. This is likely related to the tremendous improvement in both hardware and software of kinetic technology. For example, advancement from uniaxial to triaxial force plates has allowed researchers and clinicians to evaluate variables such as multidimensional CoP displacement that cannot be measured with uniaxial force plate technology. Similarly, variables that integrate force and time, such as impulse and loading rate, would have been difficult to assess before recent technology developments that permit efficient calculations of large datasets.

However, with these advances have come a plethora of approaches and parameters to measure. This review identified important heterogeneity and methodological gaps in the current published literature that may limit the clinical application of this research. The first methodological gap is the inconsistency in the selection of parameters as well as their operationalization. For instance, some studies assessed jumping and landing using vGRF only, while others measured both vGRF and posterior GRF, without justifying their selection. All selected parameters may have relevance, but researchers should justify their selection to readers in light of their objectives. The lack of operationalization of commonly reported parameters also creates confusion. For example, using “vGRF” and “peak vGRF” made it challenging to discern if these parameters were the same or different measures across studies (i.e., did “vGRF” consider multiple points in time across the force-time curve, or only the time at which maximal vGRF was achieved?). Together, the heterogeneity and the lack of operationalization for evaluating specific parameters makes it challenging to determine the most clinically relevant parameters in the ACLR population.

The second methodological gap was the heterogeneity in the kinetic measurement systems setup, as the type of selected system and sampling frequency varied across studies assessing the same task(s). Other important methodological gaps include the inconsistency in reporting important protocol items such as participant preparation (e.g., warm-up details, hand position, shoed vs. barefoot) and protocol details (e.g., starting/ending positons, eyes open vs. closed, and single vs. double-leg landing). These methodological considerations can influence the reported outcomes. For instance, a gluteal warm up program may enhance force production while performing squat jumps after 8 min of recovery [167]. Similarly, arm swings while performing vertical counter movement jumps can increase jump height by 38% [174]. Therefore, when assessing a task such as CMJs using a force plate, our methodological reporting consideration may guide future papers to define the parameters of interest, justify parameter selections, report on the force plate details, and report the sampling frequency used. Authors should also report warm-up program details, whether participants were shoed or not, and participants’ hand placement while performing the CMJs. When reporting on the CMJ activity, we recommend authors report on the direction of jump, single−/double-leg jumping or landing, and the immediate tasks performed after landing. Researchers need to consider and justify their approaches a priori and ensure that they report them as such. Our findings underscore the need to develop standardized reporting guidelines to enhance the quality of future studies and advance this field of research.

Though we aimed to describe the use of kinetic measurement systems in post-ACLR individuals, it was not our intent to make recommendations regarding which kinetic parameters to examine to inform RTS decisions following ACLR. We did not examine reported outcomes in our included studies, but rather conducted a detailed review of the reported approaches. The findings from the current review may have implications for future research and, consequently, clinical application. The suggested methodological considerations (Table 7) will assist in standardizing the reporting of important protocol details in future studies, to allow future meta-analyses which may better inform clinical practice.

The secondary purpose of the current review was to explore papers studying potential associations between kinetic measures and PROMs. Our findings highlighted an evidence gap as we identified only 6 studies that investigated this potential relationship [9, 92, 98, 117, 158, 161]. The identified studies demonstrated inconsistencies in the parameters measured and the types of PROMs utilized. Of the 6 studies, 5 were published since 2018 [9, 92, 98, 117, 158]. This may indicate an emerging research area acknowledging psychosocial factors that may interact with kinetic measurement outcomes; future studies are needed to further understand the extent of this relationship. Due to the heterogeneity in kinetic parameters and PROMs used, and the limited number of papers identified, a systematic review to examine the association between specific kinetic parameters and specific PROMs may not produce clinically useful findings at the current time, but this appears to be a developing field of investigation.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first review detailing different parameters and methodological protocols applied to assess various tasks utilizing kinetic measurement systems in the ACLR patient population. In this scoping review, we followed a systematic approach, suggested by the framework of Arksey and O’Malley [7]. We searched for peer-reviewed published literature and did not restrict by publication date or language; this allowed us to identify the widest base of relevant studies on the use of kinetic measurement systems in individuals following ACLR and additionally identify the methodological gaps in the reported literature. The study team was a multidisciplinary group, including individuals with diverse expertise in research methodology, evidence synthesis, orthopaedic surgery, sport and exercise therapy, knee injury rehabilitation, kinesiology, and engineering. This reduced ambiguity and uncertainties related to study selection and reporting [93].

This review, however, has limitations. We reported only methodological considerations, and therefore cannot state what impact those methodologies had on study outcomes. Prior to comparing outcomes, we must first understand the various methodological approaches. Our intent was not to settle on a single agreement for methodological approach or outcomes post-ACLR, but rather to emphasize the need for clear and detailed methodology reporting to allow comparisons across studies to advance our understanding of the current evidence.

Future direction

The suggested methodological considerations (Table 7) in this review provide important information to support further research aimed at developing and validating a methodological reporting standard checklist for kinetic measurement systems to assess individuals following ACLR. Standardizing reporting of methodology will improve our understanding as to which kinetic measurement systems and protocols may be most clinically relevant in the ACLR population. These reporting considerations can subsequently be applied in future work to objectively inform patients and clinicians when discussing RTS decisions following ACLR. This review highlights areas for potential future systematic reviews to identify the most useful parameters, tasks, and approaches to use in individuals following ACLR.

Conclusion

There has been substantial advancement in utilizing kinetic measurement systems in individuals post-ACLR. However, this advancement has been challenged by heterogeneity in approaches and methodological gaps in reporting. Clear and accurate reporting in clinical outcome research is important to demonstrate valid outcomes and to compare outcomes across studies. Therefore, our study suggests methodological considerations as a mechanism to assist authors in the reporting of essential items needed to improve reproducibility and subsequent quality of research in this area. Moreover, our review recommends future systematic reviews to examine the most useful kinetic parameters and approaches to follow when assessing specific functional tasks performed by individuals following ACLR. However, a systematic review to examine the association between specific kinetic parameters and specific PROMs may not produce clinically useful findings at the current time due to the scarcity and heterogeneity in the available evidence.

Availability of data and materials

All included papers and data extraction spreadsheet are available upon request.

References

Ahmadi P, Salehi R, Mehravar M, Goharpey S, Negahban H (2020) Comparing the effects of external focus of attention and continuous cognitive task on postural control in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed athletes. Neurosci Lett. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134666

Akhbari B, Salavati M, Ahadi J, Ferdowsi F, Sarmadi A, Keyhani S, Mohammadi F (2015) Reliability of dynamic balance simultaneously with cognitive performance in patients with ACL deficiency and after ACL reconstructions and in healthy controls. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:3178–3185

Alonso AC, Greve JMD, Camanho GL (2009) Evaluating the center of gravity of dislocations in soccer players with and without reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using a balance platform. Clinics 64:163–170

An KO, Park GD, Lee JC (2015) Effects of acceleration training 24 weeks after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on proprioceptive and dynamic balancing functions. J Phys Ther Sci 27:2825–2828

Andrade MS, Cohen M, Picarro IC, Silva AC (2002) Knee performance after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Isokinet Exerc Sci 10:81–86

Ardern CL (2015) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction—not exactly a one-way ticket back to the preinjury level: a review of contextual factors affecting return to sport after surgery. Sports Health 7:224–230

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8:19–32

Armitano-Lago CN, Morrison S, Hoch JM, Bennett HJ, Russell DM (2020) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed individuals demonstrate slower reactions during a dynamic postural task. Scand J Med Sci Sports 30:1518–1528

Azus A, Teng H-L, Tufts L, Wu D, Ma CB, Souza RB, Li X (2018) Biomechanical factors associated with pain and symptoms following anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. PM & R 10:56–63

Baczkowicz D, Skomudek A (2013) Assessment of neuromuscular control in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 15:205–214

Bartels T, Brehme K, Pyschik M, Pollak R, Schaffrath N, Schulze S, Delank K-S, Laudner K, Schwesig R (2019) Postural stability and regulation before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction - a two years longitudinal study. Phys Ther Sport 38:49–58

Bell DR, Blackburn JT, Hackney AC, Marshall SW, Beutler AI, Padua DA (2014) Jump-landing biomechanics and knee-laxity change across the menstrual cycle in women with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train 49:154–162

Birchmeier T, Lisee C, Geers B, Kuenze C (2019) Reactive strength index and knee extension strength characteristics are predictive of single-leg hop performance after anteriorc ligament reconstruction. J Strength Cond Res 33:1201–1207

Birmingham TB, Kramer JF, Kirkley A, Inglis JT, Spaulding SJ, Vandervoort AA, Timothy Inglis J, Spaulding SJ, Vandervoort AA, Kramer JF, Kirkley A, Inglis JT, Spaulding SJ, Vandervoort AA (2001) Knee bracing after ACL reconstruction: effects on postural control and proprioception. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33:1253–1258

Bjornaraa J, Di Fabio RP (2011) Knee kinematics following acl reconstruction in females; the effect of vision on performance during a cutting task. Int J Sports Phys Ther 6:271–284

Blache Y, Pairot de Fontenay B, Argaud S, Monteil K (2017) Asymmetry of inter-joint coordination during single leg jump after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Int J Sports Med 38:159–167

Blackburn JT, Pietrosimone B, Harkey MS, Luc BA, Pamukoff DN (2016) Inter-limb differences in impulsive loading following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in females. J Biomech 49:3017–3021

Blackburn JT, Pietrosimone B, Harkey MS, Luc BA, Pamukoff DN (2016) Quadriceps function and gait kinetics after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:1664–1670

Blackburn JT, Pietrosimone B, Spang JT, Goodwin JS, Johnston CD (2020) Somatosensory function influences aberrant gait biomechanics following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Res 38:620–628

Blackburn T, Pietrosimone B, Goodwin JS, Johnston C, Spang JT (2019) Co-activation during gait following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech 67:153–159

Bodkin SG, Slater LV, Norte GE, Goetschius J, Hart JM (2018) ACL reconstructed individuals do not demonstrate deficits in postural control as measured by single-leg balance. Gait Posture 66:296–299

Bonfim TR, Barela JA (2005) Postural control after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Fisioterapia e Pesquisa 17:11–18

Bonfim TR, Jansen Paccola CA, Barela JA (2003) Proprioceptive and behavior impairments in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil United States 84:1217–1223

Borin SH, Bueno B, Gonelli PRG, Moreno MA (2017) Effects of hip muscle strengthening program on functional responses of athletes submitted to reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Exerc Physiol Online 20:78–87

Bramer WM, Giustini D, De Jong GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T (2016) De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in endnote. J Medical Library Association 104:240–243

Brunetti O, Filippi GM, Lorenzini M, Liti A, Panichi R, Roscini M, Pettorossi VE, Cerulli G (2006) Improvement of posture stability by vibratory stimulation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:1180–1187

Bulgheroni P, Bulgheroni MV, Andrini L, Guffanti P, Giughello A (1997) Gait patterns after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 5:14–21

Burgi CR, Peters S, Ardern CL, Magill JR, Gomez CD, Sylvain J, Reiman MP (2019) Which criteria are used to clear patients to return to sport after primary ACL reconstruction? A scoping review. Br J Sports Med 53:1154–1161

Camomilla V, Cereatti A, Cutti A, Fantozzi S, Stagni R, Vannozzi G (2017) Methodological factors affecting joint moments estimation in clinical gait analysis: a systematic review. Biomed Eng Online 16:106

Chang E, Johnson ST, Pollard CD, Hoffman MA, Norcross MF (2020) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed females who pass or fail a functional test battery do not exhibit differences in knee joint landing biomechanics asymmetry before and after exercise. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1960–1970

Chang EW, Johnson S, Pollard C, Hoffman M, Norcross M (2018) Landing biomechanics in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed females who pass or fail a functional test battery. Knee 25:1074–1082

Chavda S, Bromley T, Jarvis P, Williams S, Bishop C, Turner AN, Lake JP, Mundy PD (2018) Force-time characteristics of the countermovement jump. Strength Cond J 40:67–77

Chaves SF, Marques NP, Silva RLE, Reboucas NS, de Freitas LM, de Paula Lima PO, de Oliveira RR (2012) Neuromuscular efficiency of the vastus medialis obliquus and postural balance in professional soccer athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2:121–126

Clark RA, Bell SW, Feller JA, Whitehead TS, Webster KE (2017) Standing balance and inter-limb balance asymmetry at one year post primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: sex differences in a cohort study of 414 patients. Gait Posture 52:318–324

Clark RA, Howells B, Pua Y-H, Feller J, Whitehead T, Webster KE (2014) Assessment of standing balance deficits in people who have undergone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using traditional and modern analysis methods. J Biomech 47:1134–1137

Colne P, Thoumie P (2006) Muscular compensation and lesion of the anterior cruciate ligament: contribution of the soleus muscle during recovery from a forward fall. Clin Biomech 21:849–859

Cristiani R, Mikkelsen C, Forssblad M, Engstrom B, Stalman A, Engström B, Stålman A (2019) Only one patient out of five achieves symmetrical knee function 6 months after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27:3461–3470

Culvenor AG, Alexander BC, Clark RA, Collins NJ, Ageberg E, Morris HG, Whitehead TS, Crossley KM (2016) Dynamic single-leg postural control is impaired bilaterally following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: implications for reinjury risk. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 46:357–364

Czamara A, Tomaszewski W (2011) Critera for return to sport training in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). Polish J Sport Med 27:19–31

Dan MJ, Lun KK, Dan L, Efird J, Pelletier M, Broe D, Walsh WR (2019) Wearable inertial sensors and pressure MAT detect risk factors associated with ACL graft failure that are not possible with traditional return to sport assessments. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 5:e000557

Dashti Rostami K, Alizadeh M, Minoonejad H, Thomas A, Yazdi H (2020) Relationship between electromyographic activity of knee joint muscles with vertical and posterior ground reaction forces in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed patients during a single leg vertical drop landing task. Res Sport Med 28:1–14

Davies WT, Myer GD, Read PJ (2020) Is it time we better understood the tests we are using for return to sport decision making following ACL reconstruction? A critical review of the hop tests. Sports Med 50:485–495

Decker MJ, Torry MR, Noonan TJ, Riviere A, Sterett WI (2002) Landing adaptations after ACL reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:1408–1413

Denti M, Randelli P, Lo Vetere D, Moioli M, Bagnoli I, Cawley PW (2000) Motor control performance in the lower extremity: normals vs. anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees 5–8 years from the index surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:296–300

DiFabio M, Slater LV, Norte G, Goetschius J, Hart JM, Hertel J (2018) Relationships of functional tests following ACL reconstruction: exploratory factor analyses of the lower extremity sssessment protocol. J Sport Rehabil 27:144–150

Dingenen B, Janssens L, Claes S, Bellemans J, Staes FF (2015) Postural stability deficits during the transition from double-leg stance to single-leg stance in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed subjects. Hum Mov Sci 41:46–58

Dingenen B, Janssens L, Claes S, Bellemans J, Staes FF (2016) Lower extremity muscle activation onset times during the transition from double-leg stance to single-leg stance in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed subjects. Clin Biomech 35:116–123

Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA (2010) Functional tests should be accentuated more in the decision for ACL reconstruction. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 18:1517–1525

Elias ARC, Hammill CD, Mizner RL (2015) Changes in quadriceps and hamstring cocontraction following landing instruction in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 45:273–280

Evans-Pickett A, Davis-Wilson HC, Luc-Harkey BA, Blackburn JT, Franz JR, Padua DA, Seeley MK, Pietrosimone B (2020) Biomechanical effects of manipulating peak vertical ground reaction force throughout gait in individuals 6–12 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2020.105014

Ferdowsi F, Shadmehr A, Mir SM, Olyaei G, Talebian S, Keihani S (2018) The reliability of postural control method in athletes with and without ACL reconstruction: a transitional task. J Phys Ther Sci 30:896–901

Flanagan EP, Galvin L, Harrison AJ (2008) Force production and reactive strength capabilities after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train 43:249–257

de Fontenay BP, Argaud S, Blache Y, Monteil K (2014) Motion alterations after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of the injured and uninjured lower limbs during a single-legged jump. J Athl Train 49:311–316

Ford KR, Schmitt LC, Hewett TE, Paterno MV (2016) Identification of preferred landing leg in athletes previously injured and uninjured: a brief report. Clin Biomech 31:113–116

Frank BS, Gilsdorf CM, Goerger BM, Prentice WE, Padua DA (2014) Neuromuscular fatigue alters postural control and dagittal plane hip biomechanics in active females with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Health 6:301–308

Furlanetto TS, Peyré-Tartaruga LA, Do Pinho AS, Da Bernardes ES, Zaro MA (2016) Proprioception, body balance and functionality in individuals with ACL reconstruction. Acta Ortop Bras Sociedade Brasileira de Ortopedia e Traumatologia 24:67–72

Gandolfi M, Ricci M, Sambugaro E, Vale N, Dimitrova E, Meschieri A, Grazioli S, Picelli A, Foti C, Rulli F, Smania N (2018) Changes in the sensorimotor system and semitendinosus muscle morphometry after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective cohort study with 1-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:3770–3779

Goetschius J, Hertel J, Saliba SA, Brockmeier SF, Hart JM (2018) Gait biomechanics in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees at different time frames postsurgery. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50:2209–2216

Goetschius J, Kuenze CM, Saliba S, Hart JM (2013) Reposition acuity and postural control after exercise in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45:2314–2321

Gokeler A, Bisschop M, Myer GD, Benjaminse A, Dijkstra PU, van Keeken HG, van Raay JJAM, Burgerhof JGM, Otten E (2016) Immersive virtual reality improves movement patterns in patients after ACL reconstruction: implications for enhanced criteria-based return-to-sport rehabilitation. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc 24:2280–2286

Gokeler A, Hof AL, Arnold MP, Dijkstra PU, Postema K, Otten E (2010) Abnormal landing strategies after ACL reconstruction. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20:e12–e19

Grooms DR, Chaudhari A, Page SJ, Nichols-Larsen DS, Onate JA (2018) Visual-motor control of drop landing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train 53:486–496

Harrison EL, Duenkel N, Dunlop R, Russell G (1994) Evaluation of single-leg standing following anterior cruciate ligament surgery and rehabilitation. Phys Ther 74:245–252

Head PL, Kasser R, Appling S, Cappaert T, Singhal K, Zucker-Levin A (2019) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and dynamic stability at time of release for return to sport. Phys Ther Sport 38:80–86

Heinert B, Willett K, Kernozek TW (2018) Influence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on dynamic postural control. Int J Sports Phys Ther 13:432–440

Hoch JM, Sinnott CW, Robinson KP, Perkins WO, Hartman JW (2018) The examination of patient-reported outcomes and postural control measures in patients with and without a history of ACL reconstruction: a case control study. J Sport Rehabil 27:170–176

Hoffman M, Schrader J, Koceja D (1999) An investigation of postural control in postoperative anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction patients. J Athl Train 34:130–136

Holsgaard-Larsen A, Jensen C, Mortensen NHM, Aagaard P (2014) Concurrent assessments of lower limb loading patterns, mechanical muscle strength and functional performance in ACL-patients - a cross-sectional study. Knee 21:66–73

Howells BE, Ardern CL, Webster KE (2011) Is postural control restored following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:1168–1177

Howells BE, Clark RA, Ardern CL, Bryant AL, Feller JA, Whitehead TS, Webster KE (2013) The assessment of postural control and the influence of a secondary task in people with anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees using a Nintendo Wii balance board. Br J Sports Med 47:914–919

Jenkins SPR (2005) Sports science handbook : the essential guide to kinesiology, sport and exercise science. Multi-Science, Essex

Johnston CD, Goodwin JS, Spang JT, Pietrosimone B, Blackburn JT (2019) Gait biomechanics in individuals with patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts. J Biomech 82:103–108

Karasel S, Akpinar B, Gulbahar S, Baydar M, El O, Pinar H, Tatari H, Karaoglan O, Akalin E (2010) Clinical and functional outcomes and proprioception after a modified accelerated rehabilitation program following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 44:220–228

Karatsidis A, Bellusci G, Schepers H, de Zee M, Andersen M, Veltink P (2016) Estimation of ground reaction forces and moments during gait using only inertial motion capture. Sensors 17:75

Karatsidis A, Jung M, Schepers H, Bellusci G, de Zee M, Veltink P, Andersen M (2019) Musculoskeletal model-based inverse dynamic analysis under ambulatory conditions using inertial motion capture. Med Eng Phys 65:68–77

Kilic O, Alptekin A, Unver F, Celik E, Akkaya S (2018) Impact differences among the landing phases of a drop vertical jump in soccer players. Sport Mont 16:9–14

King E, Richter C, Daniels KAJ, Franklyn-Miller A, Falvey E, Myer GD, Jackson M, Moran R, Strike S (2021) Can biomechanical testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction identify athletes at risk for subsequent ACL injury to the contralateral uninjured limb? Am J Sports Med 49:609–619

King E, Richter C, Franklyn-Miller A, Daniels K, Wadey R, Jackson M, Moran R, Strike S (2018) Biomechanical but not timed performance asymmetries persist between limbs 9 months after ACL reconstruction during planned and unplanned change of direction. J Biomech 81:93–103

King E, Richter C, Franklyn-Miller A, Daniels K, Wadey R, Moran R, Strike S (2018) Whole-body biomechanical differences between limbs exist 9 months after ACL reconstruction across jump/landing tasks. Scand J Med Sci Sports 28:2567–2578

King E, Richter C, Franklyn-Miller A, Wadey R, Moran R, Strike S (2019) Back to normal symmetry? Biomechanical variables remain more asymmetrical than normal during jump and change-of-direction testing 9 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 47:1175–1185

Kocak FU, Ulkar B, Özkan F (2010) Effect of proprioceptive rehabilitation on postural control following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Phys Ther Sci 22:195–202

Kouvelioti V, Kellis E, Kofotolis N, Amiridis I (2015) Reliability of single-leg and double-leg balance tests in subjects with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and controls. Res Sports Med 23:151–166

Krafft FC, Stetter BJ, Stein T, Ellermann A, Flechtenmacher J, Eberle C, Sell S, Potthast W (2017) How does functionality proceed in ACL reconstructed subjects? Proceeding of functional performance from pre- to six months post-ACL reconstruction. PLoS One 12:e0178430

Królikowska A, Czamara A, Reichert P (2018) Between-limb symmetry during double-leg vertical hop landing in males an average of two years after ACL reconstruction is highly correlated with postoperative physiotherapy supervision duration. Appl Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8122586

Królikowska A, Czamara A, Reichert P (2018) Ocena symetrii obciążania kończyn dolnych w fazie lądowania skoków u mężczyzn średnio 2 lata od rekonstrukcji więzadła krzyżowego przedniego stawu kolanowego i nadzorowanej pooperacyjnej fizjoterapii trwającej krócej niż 6 miesięcy. Polish J Sport Med/Medycyna Sportowa 34:155–165

Krolikowska A, Czamara A, Szuba L, Reichert P (2018) The effect of longer versus shorter duration of supervised physiotherapy after ACL reconstruction on the vertical jump landing limb symmetry. Biomed Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7519467

Kuster MS, Grob K, Kuster M, Wood GA, Gächter A (1999) The benefits of wearing a compression sleeve after ACL reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31:368–371

Labanca L, Laudani L, Menotti F, Rocchi J, Mariani PP, Giombini A, Pigozzi F, Macaluso A (2016) Asymmetrical lower extremity loading early after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is a significant predictor of asymmetrical loading at the time of return to sport. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 95:248–255

Labanca L, Rocchi JE, Laudani L, Guitaldi R, Virgulti A, Mariani PP, Macaluso A (2018) Neuromuscular electrical stimulation superimposed on movement early after ACL surgery. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50:407–416

Lam MH, Fong DTP, Yung PSH, Ho EPY, Fung KY, Chan KM (2011) Knee rotational stability during pivoting movement is restored after anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 39:1032–1038

Lanier AS, Knarr BA, Stergiou N, Snyder-Mackler L, Buchanan TS (2020) ACL injury and reconstruction affect control of ground reaction forces produced during a novel task that simulates cutting movements. J Orthop Res 38:1746–1752

Lee JH, Han S-B, Park J-H, Choi J-H, Suh DK, Jang K-M (2019) Impaired neuromuscular control up to postoperative 1 year in operated and nonoperated knees after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Medicine (Baltimore). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015124

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lim BO, Shin HS, Lee YS (2015) Biomechanical comparison of rotational activities between anterior cruciate ligament- and posterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:1231–1238

Lim J-M, Cho J-J, Kim T-Y, Yoon B-C (2019) Isokinetic knee strength and proprioception before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison between home-based and supervised rehabilitation. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 32:421–429

Luc-Harkey BA, Franz JR, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Hackney AC, Pietrosimone B (2018) Real-time biofeedback can increase and decrease vertical ground reaction force, knee flexion excursion, and knee extension moment during walking in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Biomech 76:94–102

Luc-Harkey BA, Franz JR, Hackney AC, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Pietrosimone B (2018) Lesser lower extremity mechanical loading associates with a greater increase in serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein following walking in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech 60:13–19

Luc-Harkey BA, Franz JR, Losina E, Pietrosimone B (2018) Association between kinesiophobia and walking gait characteristics in physically active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Gait Posture 64:220–225

Luc-Harkey BA, Harkey MS, Stanley LE, Blackburn JT, Padua DA, Pietrosimone B (2016) Sagittal plane kinematics predict kinetics during walking gait in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech 39:9–13

L’Insalata JC, Beim GM, Fu FH (2000) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction - allografts. In Controversies in orthopedic sports medicine. Human Kinetics, c2000, Champaign, p 53–61

Mantashloo Z, Letafatkar A, Moradi M (2020) Vertical ground reaction force and knee muscle activation asymmetries in patients with ACL reconstruction compared to healthy individuals. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:2009–2014

Markstrom JL, Grip H, Schelin L, Hager CK (2020) Individuals with an anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knee display atypical whole body movement strategies but Normal knee robustness during side-hop landings: a finite helical Axis analysis. Am J Sports Med 48:1117–1126

Markstrom JL, Schelin L, Hager CK (2018) A novel standardised side hop test reliably evaluates landing mechanics for anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed persons and controls. Sport Biomech. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2018.1538385

Mattacola CG, Jacobs CA, Rund MA, Johnson DL (2004) Functional assessment using the step-up-and-over test and forward lunge following ACL reconstruction. Orthopedics 27:602–608

Mattacola CG, Perrin DH, Gansneder BM, Gieck JH, Saliba EN, McCue FC 3rd (2002) Strength, functional outcome, and postural stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train 37:262–268

van Melick N, van Cingel REH, Brooijmans F, Neeter C, van Tienen T, Hullegie W, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG (2016) Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med 50:1506–1515

Melińska A, Czamara A, Szuba L, Będziński R, Klempous R (2015) Balance assessment during the landing phase of jump-down in healthy men and male patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Acta Polytech Hungarica 12:77–91

Mengarelli A, Cardarelli S, Tigrini A, Fioretti S, Verdini F (2019) Kinetic data simultaneously acquired from dynamometric force plate and Nintendo Wii balance board during human static posture trials. Data in Brief. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.105028