Abstract

Diffuse CO2 emission surveys were carried out at São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands, Cape Verde, archipelago to investigate the relationship between diffuse CO2 degassing and volcanic activity. Total amounts of diffuse CO2 discharged through the surface environment of the islands of São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo were estimated in 226, 50, and 828 t d−1, respectively. The highest CO2 efflux values of the three volcanic islands systems were observed at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (up to 15.7 kg m−2 d−1). Statistical graphical analysis of the data suggests two geochemical populations for the diffuse CO2 emission surveys. The geometric mean of the peak population, expressed as a multiple of the geometric mean of the background population, seems to be the best diffuse CO2 emission geochemical parameter to correlate with the volcanic activity (age of the volcanism) for these three island volcanic systems at Cape Verde. This observation is also supported by helium isotopic signature observed in the Cape Verde’s fluids, fumaroles, and ground waters. This study provides useful information about the relationship between diffuse CO2 degassing and volcanic activity at Cape Verde enhancing the use of diffuse CO2 emission as a good geochemical tool, for volcanic monitoring at Cape Verde as well as other similar volcanic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gases emitted from a volcano are usually released as visible emanations from the main crater areas (as plumes and fumaroles) as well as through the surface of the volcano as diffuse degassing. This last type of degassing can be as important as visible emissions (Baubron et al. 1990; Allard et al. 1991; Chiodini et al. 1996; Hernández et al. 1998, 2001a, 2003, 2012b; Gerlach et al. 2001; Rogie et al. 2001; Salazar et al. 2001; Pérez et al. 2004, 2013; Padrón et al. 2008). Among volcanic gases, CO2 is widely used in volcano gas studies and monitoring because it is one of the first gas species released from ascending magma, and it is considered conservative (Gerlach 1986). The study of diffuse CO2 degassing is important for gas budgets of volcanoes (Burton et al. 2013; Hards 2005; Pérez et al. 2011) and for monitoring volcanic activity, since the large emissions of CO2 into the atmosphere (Gerlach et al. 2001; Hernández et al. 2001a; Granieri et al. 2006; Arpa et al. 2013; Pérez et al. 2013; Melián et al. 2014) as well as changes in the temporal evolution of CO2 efflux (Salazar et al. 2002; Carapezza et al. 2004, 2012; Pérez et al. 2006, 2012; Liuzzo et al. 2013; De Gregorio et al. 2014; Padilla et al. 2014) can be correlated with volcanic activity.

Efforts have been made to obtain a CO2 flux baseline for a given volcanic system (Salazar et al. 2001). However, very few studies have been focused on investigating the relationship between the magnitude of diffuse CO2 emissions and volcanic activity (eruptive recurrence) at different volcanic systems in similar geological setting (i.e., volcanic islands that belong to the same archipelago). Notsu et al. (2006) proposed a five-stage evolutionary model for the release of volcanic gas based on the relationship between level of volcanic activity and degassing pattern (diffuse vs. plume CO2 emission). This model represents an important approach to estimate both visible and non-visible emissions from different volcanoes in a similar state of activity. Williams-Jones et al. (2000) investigated the diffuse degassing (radon and CO2) at three subduction-related volcanoes: Poás and Arenal in Costa Rica and Galeras in Colombia. Although they found that fracturing, hydrothermal development and regional structure are the main variables that may affect flank degassing; this study was carried out at volcanoes with similar level of volcanic activity (all of them exhibiting plume emission and with frequent eruption episodes). The main purpose of this study is to investigate first the relationship between diffuse CO2 degassing and volcanoes of the Cape Verde, a hot spot archipelago (Holm et al. 2006), with different levels of volcanic activity in the same geological setting. To do this, we have performed a soil gas study at three different volcanic systems: São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands, which belong to different geological epochs, aimed at (1) quantifying the rate at which CO2 is diffusely degassed from the three volcanic islands, (2) identifying and defining the structures controlling the degassing process, and (3) investigating of the relationship between volcanic activity and diffuse CO2 degassing.

Geological setting

The Cape Verde archipelago (4,033 km2) is located in the Atlantic Ocean, approximately 800 km west of Senegal, at latitudes between 14° 40′ and 17° 30′ N and longitudes between 21° 30′ and 25° 30′ W (Figure 1). The archipelago consists of ten islands and eight minor islets arranged in a westward opened horseshoe shape. The islands of Cape Verde are divided into the Northern or Barlovento (windward) islands (Santo Antão, São Vicente, Santa Luzia, São Nicolau, Sal, and Boa Vista) and Southern or Sotavento (leeward) islands (Maio, Santiago, Fogo, and Brava). The climate ranges from arid to semi-arid with two seasons: a moderate season (from November to June) and a ‘wet season’ (July to October) (Semedo and Brito 1995). The vegetation of the Cape Verde islands is sparse and consists of the drought-resistant species, mainly. The islands with most vegetation cover (Santo Antão, Fogo, and São Nicolau) also hold the largest vegetation cover in endemic biotopes. The archipelago is severely degraded, if not, places are already a desert: Sal, Boavista, and Maio (Lobin and Zizka 1987; Brochmann et al. 1997; Olehowski et al. 2008).

Cape Verde is consists of an intra-plate volcanic chain, Cape Verde Rise, the world’s highest intra-plate elevation in the ocean crust (Lodge and Helffrich 2006) and occupies a position on the passive margin of the African plate, coincident with important residual geoid and gravimetric and heat flow anomalies related to the well-characterized Cape Verde mantle plume (Courtney and White, 1986).The volcanic activity is originated by a hot spot located under a broad lithospheric swell that reflects the low velocity of the plate relative to the mantle plume (Holm et al. 2006). The onset of volcanism on the easternmost islands, which are deeply eroded and older, is in the middle Miocene (approximately 15 million years (Ma); Vinnik et al. 2012). Volcanic activity continued in Pliocene but on a reduced scale and migrated from east to west about approximately 6 Ma ago (Mitchell et al. 1983; Plesner et al. 2002; Duprat et al. 2007), which continues until today (Holm et al. 2008). During Holocene, volcanic activity occurred at Brava, Santo Antão, and Fogo islands (Foeken et al. 2009), but only Fogo Island has registered numerous historical eruptions since the first Portuguese colonization in the fifteenth century (Ribeiro 1960). The most recent eruptions occurred in 1951, 1995, and 2014 to 2015 (Ribeiro 1960; Torres et al. 1997; Heleno da Silva et al. 1999; Silva et al. 2015).

São Vicente island

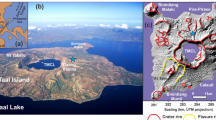

São Vicente island (227 km2) is one of the Barlovento Islands. Its outline resembles that of a rhombus with a major (E to W) diagonal of about 24 km and a minor (N to S) diagonal of about 16 km. According to Ancochea et al. (2010), São Vicente island arose in two main phases of construction: (i) the early phase, building up the lower São Vicente edifice (6.1 to 4.6 Ma) initiated as a shield volcano of greater dimensions than the present island, and (ii) the second phase started after the Praia Grande lateral collapse (4.5 Ma) and consisted of a refilling of the depression generated by landslide (4.5 to 1.3 Ma). This formation represents the upper São Vicente edifice. The recent volcanism (0.33 Ma; Jørgensen and Holm, 2002) is represented by a few well-preserved strombolian cones and some lava flows that were emitted to form land platforms gained from the sea at the east and northeast of island (Baia das Gatas, Calhau, Vulcão Viana, and Curral de João Paula) (Figure 2a).

Sampling sites location. Location of sampling sites (black dots) of diffuse CO2 efflux and sampling sites for 13δC (CO2) (open circles) at (a) São Vicente, (b) Brava, and (c) Fogo islands. Sampling sites of diffuse CO2 efflux and 13δ C (CO2) (white dots) correspond to (d) the summit crater of Pico do Fogo where yellow line indicates the extension of fumarolic area. Topographic map modified from Torres et al. 1998 with 50 m contour lines.

Brava island

Brava (67 km2) is the westernmost island and it is located 18 km west of Fogo. The morphology of the island is characterized by a broadly circular shape and steep coastal slopes, cut by deep erosional valleys and extremely irregular plateau with a few major fluvial valleys and several closed (or formerly closed) depressions that correspond to modern phreatomagmatic craters and phonolite volcanic domes. Three volcano-stratigraphic units are identified: (i) Brava seamount stage or lower unit composed of alternating pillow lavas, hyaloclastites, and pillow breccia accumulations (approximately 3 to 2 Ma); (ii) alkaline-carbonatite complex (middle unit) produced by intrusions from shallow magma chambers (approximately 1.9 to 1.3 Ma) which have contributed to the sub-aerial development of the island; and (iii) a major erosive event and uplift pre-dating the younger volcanism (approximately 1.3 to 0.3 Ma) exposed the plutonic rocks (Madeira et al. 2010). During the last 300 ka, a sub-aerial, post-erosional volcanic phase covered the surface of the island with phonolite lava flows, domes, and pyroclasts which present a very fresh morphology, indicating a probable Holocene age (Madeira et al. 2010). Although no historical eruptions have occurred at Brava, the island is seismically active suggesting the occurrence of shallow intrusive activity. Recent seismic data (Faria and Fonseca, 2014) indicate that seismic activity is dominated by volcano-tectonic events with a local magnitude between 0.7 and 3.2, and most have epicenters offshore. Finally, it is important to point out that at Brava there are two areas (Baleia and Vinagre; Figure 2b) characterized by high -soil CO2 contents which have produced several lethal accidents to animals as doves and goats (field observations).

Fogo Island

Fogo (476 km2) is the fourth largest island in the archipelago of Cape Verde with a roughly circular shape (approximately 25 km of a diameter). The most prominent geological feature is Chã das Caldeiras, consisting of a 9-km north- to- south wide caldera opened towards the east and bounded on its northern, western, and southern sides by continuous and extremely steep cliff known as the Bordeira (approximately 20 km along). Pico do Fogo (2,829 m.a.l.s.) grew up inside of this caldera and is one of the world’s most active volcanoes with about 30 eruptions since its discovery, the last occurring in 2014 (Figure 2c). The geological evolution of Fogo Island has been well reported by a few authors (Machado, 1965; Day et al. 1999). Day et al. (1999) and Foeken et al. (2009) proposed four phases for the geological evolution of Fogo: (i) uplift seamount series (approximately 4.5 Ma) composed of carbonatites and alkaline basalts; (ii) the Monte Barro group which includes the first sub-aerial lavas; (iii) the Monte Amarelo group which represents a period of intense volcanism which ended with the giant lateral summit collapse (approximately 123 to 62 ka; Foeken et al. 2009); and (iv) the post-collapse Chã das Caldeiras group (62 ka to present), where most of volcanic activity has occurred at the Chã das Caldeiras plain and a homogeneous distribution of numerous cinder cones outside the caldera along the three broadly radial volcanic rift zones (W, NNE, and SSE) of the island. Most of early historical eruptions (during the seventh and eighteen centuries) have occurred at the summit area of Pico do Fogo, whereas recent eruptions in Chã das Caldeiras have occurred mainly along WSW-ENE- oriented fissures (Day et al. 1999).

Pico do Fogo volcano is characterized by the existence of a fumarolic field situated NW inside the summit crater (Figure 2d) and composed by low- and high-temperature gas discharges (90°C to 100°C and above 200°C, respectively) with widespread sulfur precipitates at the surface, typical of hydrothermal alteration (Melián et al. 2008; Silva et al. 2011; Dionis et al. 2014). Faria and Fonseca (2014) reported that the most frequent seismic events at Fogo Islands are cigar-shaped, hybrid, long-period, volcano-tectonic events and spasmodic tremors. Volcano-tectonic events recorded on Fogo usually have a local magnitude ranging between 0.1 and 3.5, with epicenters located mostly inside Chã das Caldeiras and focal depths between 7 and 0 km (relative to the sea level), but most frequently near sea level.

Methods

In 2008, 2009, and 2010, three soil diffuse CO2 emission surveys were carried out at São Vicente, Fogo, and Brava islands, respectively. To obtain a homogeneous distribution of sampling sites at each island, 400, 468, and 228 sites were selected for São Vicente, Fogo, and Brava islands, respectively (Figure 2), depending of the local geology, the main volcano-tectonic features and the accessibility. Within 468 sites selected for Fogo Island, 51 measurements were performed inside the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (0.142 km2) (Figure 2d). All field works at Cape Verde archipelago were carried out during dry periods to minimize the influence of precipitation.

Soil CO2 flux and chemical and isotopic composition

Measurements of soil CO2 efflux were performed following the accumulation chamber method (Parkinson 1981) using two portable soil CO2 flux instruments (West Systems, Italy). One of them was equipped with a non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) CO2 analyzer LICOR-820, with a measurement range of 0 to 2,000 ppmV, an accuracy of concentration reading of 2% and a repeatability of ±5%. Due to the high-diffuse CO2 emissions that are present in the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (Fogo Island) and Baleia and Vinagre areas (Brava Island), the soil CO2 flux meter used at these areas was equipped with a Dräger Polytron IR CO2 detector. It was composed by a double beam infrared CO2 sensor compensated for temperature and atmospheric pressure. The accuracy on the flux measurement ranges between ±25% (for 0.5 to 5 mol m−2 d−1) and ±10% (for 350 to 1,500 mol m−2 d−1) and the detection limit is 1.5 g m−2 d−1. Both analyzers were interfaced to a hand-held computer running data acquisition software.

With the aim to analyze the chemical and isotopic composition of soil gases, at each site samples were collected in 10-cc glass vials with a hypodermic syringe by inserting a 50 cm stainless probe at 40 cm depth in the ground following the method described by Hinkle and Kilburn (1979). Residual gas inside the probe was always purged before sampling. Content of CO2 in the soil gas samples was analyzed by micro-chromatography with a VARIAN model 4900 (Agilent Technologies, USA) using a thermal conductivity detector and a 20-m PoraPLOT Q column using argon (Ar) as carrier gas. The temperature of the column and injector were 40°C and 60°C, respectively, and the injection time was 20 ms. The detection limit for CO2 was estimated to be about 10 ppmV and the accuracy of the measurements about 2.5% on the basis of standard sample measurements. Soil temperature was also determined by inserting a thermocouple at each sampling site at a depth of 15 to 40 cm.

The 13C/12C ratios in CO2 (expressed as δ13C-CO2‰ vs. Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB)) from soil gas samples were determined with a Thermo Finnigan MAT 253 isotopic ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) with a continuous flow injection from a Finnigan Gas Bench II (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) at the Geochemistry Laboratory of ITER-INVOLCAN (Canary Islands, Spain). The analytical error for δ13C values is ±0.1‰. To investigate the carbon isotopic composition of the soil CO2, a certain number of samples was selected for each survey (10%, 15%, and 29 % of total samples sites for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo, respectively (Figure 2). Samples for 3He/4He analyses were collected from fumarolic discharges at summit crater of Pico do Fogo (Figure 2d) and from a groundwater cold-spring (Agua Vinagre, Figure 2b) in Brava Island and were analyzed at the Geochemical Research Center (University of Tokyo, Japan) following the methodology described by Sumino et al. (2001). 3He/4He data was corrected for air-derived contributions following the method described by Craig et al. 1978. About 50-cm3 lead-glass bottles fitted with high-vacuum stopcocks at both ends were totally filled with gas (summit crater of Pico do Fogo) and water (Agua Vinagre). Dissolved helium and neon in the groundwater samples were extracted following the method described by Padrón et al. (2013). After extraction, helium isotopic ratios and helium and neon concentrations were measured following the method described by Sumino et al. 2001. The correction factor for helium isotope ratios was determined by measurement of an inter-laboratory helium standard named HESJ with recommended 3He/4He ratio of 20.63 ± 0.10 Ra (Matsuda et al. 2002).

Statistical and graphical treatment of the data

In order of distinguish the existence of different geochemical populations among acquired data, a statistical-graphical analysis (Sinclair 1974) was applied to the soil CO2 efflux data from each survey. Probability plots are a useful practical tool in the analysis of soil geochemical data because of the common normal or log-normal character of such data. The normal or log-normal populations are usually interpreted as background and peak populations with different mean values. Soil gas contour maps were constructed using sequential Gaussian simulation (sGs), provided by the sgsim program (Deutsch and Journel, 1998; Cardellini et al. 2003), allowing us to estimate the total diffuse CO2 output for each soil gas survey. The sGs procedure allows us to both interpolate the measured variable at not-sampled sites and assess the uncertainty of the total diffuse emission of carbon dioxide estimated for the entire studied area. The total emission rate of CO2 was expressed as the mean value of 100 equiprobable sGs realizations, and it uncertainty was considered as one standard deviation of the 100 emission rates obtained after the sGs procedure. Spatial distribution maps of diffuse CO2 emission were constructed using the average of the simulated values at each cell.

Results

Results are summarized in Table 1. At São Vicente Island, soil CO2 efflux values ranged from detection limit (approximately 0.5 g m−2 d−1) up to 10.1 g m−2d−1, with an average value of 1.3 g m−2d−1. The range of measured CO2 efflux values is similar to the observed at other volcanic systems like Canary Islands (Hernández et al. 2012a). In order to distinguish the existence of different geochemical populations in the São Vicente CO2 efflux data, a graphical statistical analysis was applied to the data showing two log-normal geochemical populations: background and peak (Figure 3a). Background population represented 68.2% of the total data with a mean of 0.5 g m−2 d−1 whereas peak population represented 1.7% with a mean of 7.6 g m−2d−1. An intermediate ‘threshold’ population which represents a mixing between background and peak values had a mean of 2.5 g m−2d−1 with 30.1% of the total soil CO2 efflux data. The mean value of the background population (approximately 0.5 g m−2 d−1) is smaller than the background values calculated for other volcanic system but it is similar that found in Timanfaya (approximately 0.4 g m−2 d−1) by Hernández et al. (2012a) The existence of a peak population suggests a different source to the soil CO2 degassing at São Vicente Island.

Cumulative probability plots of CO 2 efflux. (a) São Vicente Island; (b) Brava Island, and (c) Fogo Island. Solid black lines in the probability plots indicate different log-normal geochemical population in the original data. Solid gray lines indicate the separated background and peak log-normal populations.

The experimental variogram for CO2 efflux at São Vicente Island was fitted with a spherical model, nugget of 0.7, and range of 2,000 m. Following the variogram model, 100 simulations were performed over a grid of 23,132 (100 × 100 m) for an area of 227 km2. The average CO2 efflux map (Figure 4) shows that most of the island display background-like values, with the exception of an area with relatively higher CO2 efflux values (approximately 4.5 g m−2 d−1). This area is recognized by several authors (Ancochea et al. 2010; Ramalho 2011) as the main Quaternary deposits of the island (dotted black line A). No significant values were observed along areas where recent volcanism has occurred (dashed black square B). The estimated average value for the total diffuse CO2 released from São Vicente Island during this study was 226 ± 14 t d−1. Given that the area of São Vicente Island is 227 km2, we have estimated normalized value of approximately 0.9 t km−2 d−1. This value is similar to the ones reported for other volcanic systems as Timanfaya volcano (Lanzarote, Canary Islands), with a normalized value in the range of 0.16 to 2.05 t km−2 d−1 (area of 252 km2; Hernández et al. 2012a) and El Hierro, with a normalized values of approximately 0.7 t km−2 d−1 (area of 278 km2; Melián et al. 2014).

Spatial distribution map of diffuse CO 2 emission for São Vicente Island. The experimental and the modeled variogram used for the realization are showed at the bottom left. Dotted black line indicates Quaternary deposits A and dashed black square indicates B recent volcanic products with the main edifices: Curral de João Paula and Vulcão Viana. Modified volcano-stratigraphy defined by Ancochea et al. (2010).

At Brava Island, soil CO2 efflux values ranged from detection limit (approximately 0.5 g m−2 d−1) up to 1,343 g m−2d−1, with an average value of 19.2 g m−2d−1. The statistical-graphical analysis of soil CO2 efflux data indicates the presence of two log-normal geochemical populations (Figure 3b): background and peak. Background population represented 98.9% of the total data with a mean of 2.2 g m−2d−1 and a peak population represented 0.6% with a mean of 709.3 g m−2d−1. An intermediate ‘threshold’ population which represents a mixing between background and peak values had a mean of 8.7 g m−2d−1 of CO2 with 0.5% of the total soil CO2 efflux data. Peak population may be considered as representative of CO2 effluxes fed by an endogenous source as has been reported for other volcanic systems (Chiodini et al. 1998, 2001, 2008; Cardellini et al. 2003; Hernández et al. 2012a). A similar behavior is observed for São Vicente Island, with background values representing CO2 efflux produced by biological activity in the soil although significantly higher than background values of São Vicente Island. The observed difference could be explained by development of vegetation since at São Vicente soils are less vegetated than in Brava. Even if the peak population for Brava Island represents a relatively low percentage of total data, its mean value (709.3 g m−2d−1) strongly supports the contribution of a deeper source (a volcanic-hydrothermal system).

The experimental variogram for CO2 efflux at Brava Island was fitted with a spherical model, nugget of 0.65 and range of 1,450 m. Following the variogram model, 100 simulations were performed over a grid of 6,427 square cells (100 × 100 m) for an area of 67 km2. Figure 5 shows the spatial distribution of soil CO2 efflux where several areas were characterized by relatively high values located in the center of island. Madeira et al. 2010 have identified the main volcano-structural features (faults, calderas, and clusters of craters) in the center of island. One of major fault system proposed by Madeira et al. (2010), the Minhoto Fault Zone (MFZ), crosses the island in a NE-SW direction. From Figure 5, a diffuse degassing structure (Baleia DDS) can be observed, may be linked to MFZ and characterized by anomalous CO2 efflux values, the highest measured throughout the island together with those measured at Vinagre DDS. No tectonic structure seems to be associated to Vinagre DDS. The estimated averaged value for the total diffuse CO2 released from Brava Island during this study was 50 ± 10 t d−1. If we normalize this value by the area of Brava (67 km2), we obtain a value of approximately 0.7 t km−2 d−1, similar to the one obtained for São Vicente Island.

Spatial distribution map of diffuse CO 2 emission for Brava Island. The experimental and the modeled variogram used for the realization are showed at the bottom right, with modified volcano-tectonic structures defined by Madeira et al. (2010).

At Fogo Island soil CO2 efflux values ranged from approximately 0.5 (detection limit for LICOR) to 15,685 g m−2d−1, with an average value of 161.8 g m−2d−1. Maximum values were measured at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo, area of most intense surface geothermal activity in Cape Verde. As was done in the two previous cases, a statistical-graphical analysis was applied to the soil CO2 efflux data to distinguish the existence of different geochemical populations. Two log-normal geochemical populations were identified: background and peak (Figure 3c). Background population represented 94.6% of the total data with a mean of 1.02 g m−2 d−1 and peak population represented 3.0% with a mean of 1,704 g m−2d−1. An intermediate ‘threshold’ population which represents a mixing between background and peak values had a mean of 85.2 g m−2d−1 of CO2 with 2.4% of the total soil CO2 efflux data. Peak population values were measured at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo, where intense fumarolic degassing occurs.

Distinct variogram model and sGs were applied to Fogo Island and Pico do Fogo crater areas. The experimental variogram for CO2 efflux at Fogo Island was fitted with a spherical model, nugget of 0.4, and range of 5,500. Following the variogram model, 100 simulations were performed over a grid of 97,110 square cells (70 × 70 m) for an area of 476 km2 for Fogo Island. In the case of Pico do Fogo crater, a spherical variogram model with nugget of 0.1 and range of 100 m was used to construct a grid of 15,745 square cells (3 × 3 m). Inspection of the average diffuse CO2 emission map (Figure 6a) shows only background values outside the caldera, with relative maximum values approximately 4.5 g m−2 d−1. Inside the caldera no significant soil CO2 efflux values were observed, except those found inside the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (Figure 6b), possibly because most of the caldera is covered by recent lava flows. Inspection of Figure 6b shows that low soil CO2 efflux values are located at the bottom of the crater, whereas higher CO2 efflux values are observed close to the fumarolic area and other zones situated W and SE of the crater. It is remarkable that most of CO2 efflux values are 3 or 4 orders of magnitude higher than the estimated background value for Fogo Island (1.02 g m−2 d−1; in this work), supporting that anomalous CO2 degassing is mainly fed by a magmatic source. Areas with the highest diffuse CO2 efflux values were also characterized by a relatively high soil temperature (over 60°C) and by an intense surface hydrothermal alteration, which supports that degassing process is primary controlled by an advective mechanism generated by geothermal gradient (convection). The estimated average value for the total diffuse CO2 released from Fogo Island during this study was 828 ± 5 t d−1. In the case of the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (51 measuring sites), the estimated average value for the total diffuse CO2 release was 147 ± 35 t d−1. Given that the area of Fogo Island is 476 km2, we have estimated an approximately 1.7 t km−2 d−1, similar to obtained for São Vicente and Brava islands (this work) and other oceanic volcanic islands as Timanfaya volcano and El Hierro (values given above). However, normalized value for the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (1,035 t km−2 d−1; 0.142 km2) is similar to the normalized value found in other areas such as Solfatara crater (approximately 1,240 t km−2 d−1; Chiodini et al. 2001) and higher than the computed in other studies carried out at volcanic craters such as Vesuvio (82.9 t km−2 d−1; Frondini et al. 2004) and Vulcano (413.8 t km−2 d−1; Chiodini et al., 1996; 537.3 t km−2 d−1; Granieri et al. 2006) in Italy, Miyakejima (167 t km−2 d−1; Hernández et al. 2001b) in Japan, and Teide (359.8 t km−2 d−1; Pérez et al. 2013) in Canary Islands, Spain.

Spatial distribution map of diffuse CO 2 emission. For Fogo Island with modified volcano-structural map defined by Navarro 1999 (left) and for the summit crater of Pico do Fogo (right) (red dot in Figure 6 (left)). The experimental and the modeled variogram used for each realization are showed beside each map.

δ13C (CO2) isotopic composition

The δ13C (CO2) isotopic composition showed a wide range (Table 1) with an average value of −11.6‰, −11.3‰, and −17.2‰ vs. VPDB for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo island, respectively. These mean values are heavier than the typical biogenic range for vegetated soils (−20‰; Craig 1953). A binary diagram of the δ13C (CO2) versus 1/[CO2] for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo data is explainable with two geochemical end-members: air, characterized by δ13C(CO2) = −8.0‰ vs. VPDB and [CO2] = 400 ppm and biogenic CO2 (Figure 7). To define the range of the biogenic end-member, we have considered that biogenic CO2 in the soil is +4.4‰ heavier than the soil-respired CO2 produced by roots, owing to the fractionation of diffusion within the soil (Cerling et al. 1991). Since the isotopic composition of soil organic matter is less than −20‰ (Craig, 1953), the isotopic composition for the biogenic soil CO2 was defined as < −15.6‰ vs. VPDB. Figure 7 shows that most of the data plot in the shaded gray area which represents mixing of atmospheric and biogenic CO2 for all studied islands. São Vicente values (light gray circles) plot close to the air end-member and deep-seated CO2 enrichments are very small, almost negligible. Brava values (dark gray square) plot slightly above the biogenic CO2 reservoir indicating a possible mixture between deep-seated CO2 and a biogenic source that causes a graphical trend of samples along the arrows. The same behavior is observed for Fogo δ13C (CO2) values (black triangles), where most of the data plots close to the biogenic CO2 reservoir with a small atmospheric contribution and a remarkable trend to the deep-seated CO2. Samples with the strongest deep-seated CO2 contribution were collected at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo where high values of diffuse CO2 efflux were measured. The carbon isotope composition of the deep-seated CO2 at summit crater of Pico do Fogo has been well constrained by the carbon isotopic data collected from the fumaroles by Dionis et al. (2014) (−4.48‰ to −4.25‰ with a mean of −4.25‰ (±0.14‰). Anomalous CO2 efflux values (>1 kg m−2 d−1) were also characterized by having heavier carbon isotope values, indicating an endogenous feeding source for the CO2, i.e., degassing of a volcanic-hydrothermal system beneath Pico do Fogo volcano.

3He/4He isotopic composition

The air-corrected 3He/4He ratios measured in the fumarolic discharges of Pico do Fogo summit crater (Fogo Island), varied from 7.73 to 8.53 Ra (where Ra is the atmospheric 3He/4He ratio = 1.393 × 10−6; Sano et al. 2013a) in samples collected in 2009 (7.81 and 7.73 Ra; this study) and 2010 (8.53 Ra; Dionis et al. 2014). In the case of Brava, air-corrected 3He/4He ratios measured in Agua Vinagre groundwater spring in 2007 ranged between 4.86 and 6.51 Ra.

Discussion

Even when many studies have demonstrated that there is a significant relationship between diffuse CO2 degassing and volcanic activity (see references herein), this relationship has been studied at the local scale for individual volcanoes. At the regional scale for selected areas like oceanic volcanic islands in a similar geological setting, a systematic study taking into account these facts has not yet been performed. To achieve find some parameter that links both concepts, we analyzed the relationship between diffuse CO2 degassing and linked volcanic activity at Cape Verde volcanoes by applying different geochemical approaches; the results show a priori that magnitude of diffuse CO2 degassing is significantly related. However, other factors may have a more important role on defining such a relationship. The first approach we used to investigate the relationship between both parameters was comparing the mean values of the background and peak populations obtained for each of the three studied volcanic systems. Results from the statistical-graphical analysis of soil CO2 efflux data showed two overlapping log-normal geochemical populations (background (B) and peak (P)) for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands (Figure 3). The estimated mean values of the background population were 0.5, 2.2, and 1.0 g m−2 d−1 for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo, respectively, similar to the background values reported for others oceanic volcanic islands with similar soil, vegetation, and climate conditions, e.g., as the Canaries (Cumbre Vieja volcano: 1.8 g m−2 d−1, Padrón et al. 2015; El Hierro Island: 1.4 g m−2 d−1, Melián et al. 2014; and Timanfaya volcano: 0.4 g m−2 d−1, Hernández et al. 2012a). On the other hand, mean values estimated for the peak populations were 7.6, 709, and 1,704 g m−2 d−1 for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo, respectively. These peaks are from 1 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than the estimated background values, as has been also observed in other volcanic systems like Timanfaya volcano, Canary Islands (i.e., B = 0.25 g m−2 d−1 and P = 5.9 g m−2 d−1, September 2010; Hernández et al. 2012a), Vesuvio summit cone, Italy (B = 1.03 g m−2 d−1 and P = 29.5 g m−2 d−1; Cardellini et al. 2003); and Sierra Negra caldera in Galapagos (B = 3.7 g m−2 d−1 and P = 22,000 g m−2 d−1; Padrón et al. 2012). The mean peak populations of Brava and Fogo islands indicate an important deep-seated contribution characterized by high CO2 effluxes generated most likely by degassing processes of magmatic derived CO2 as has been reported for other volcanic systems (Chiodini et al. 2001, 2008; Cardellini et al. 2003). However, direct comparison of mean background and peak values does not take into account other important factors such as the characteristics of soil and climate (different levels of development of soil horizons, organic matter content, vegetation, etc.), as well as the existence of diffuse degassing structures (Chiodini et al. 2001) which can greatly contribute to peak population values. These parameters can contribute directly to the background and peak populations at any volcanic area independently of the level of volcanic activity and geological age.

Another potential useful parameter that might link diffuse CO2 degassing and volcanic activity is to compare the total diffuse CO2 emissions between the different volcanoes under study. These values can be obtained from the spatial distribution maps of soil CO2 efflux constructed by sGs, as described by Cardellini et al. (2003). The areas that contribute most to the total diffuse CO2 degassing are those characterized by anomalous soil CO2 efflux values (Figures 4, 5, and 6 for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands, respectively). Inspection of the three maps shows that main the DDSs are located in Brava Island (Baleia DDS, possible be linked to Minhoto Fault and Vinagre DDS a hidden fault or fracture) and summit crater of Pico do Fogo, which is the main diffuse CO2 degassing area not only in Fogo Island but also in Cape Verde archipelago. To eliminate the effect caused by the size of the surveyed area, CO2 emission needs to be normalized by the area (km2) of study. The normalized values of diffuse CO2 released from São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo Islands (approximately 0.9, approximately 0.7, and approximately 1.7 t km−2 d−1, respectively) were found to be similar to other volcanic systems as Timanfaya volcano (Lanzarote), with a normalized value of 0.16 to 2.05 t km−2 d−1 (252 km2; Hernández et al. 2012a) and El Hierro Island approximately 0.7 t km−2 d−1 (278 km2; Melián et al. 2014), both located in the neighboring archipelago of Canary Islands. For proper intercomparison using normalized values, selected areas of study should have similar geological and volcanic characteristics (existence of DDS). In our study, the DDS showing the most intense diffuse CO2 degassing was the summit crater of Pico do Fogo volcano. To compare its normalized value (1,035 t km−2 d−1 in 0.142 km2) with other volcanic craters in Cape Verde with surface volcano-hydrothermal gas discharges at Brava and São Vicente Islands is not possible, since they do not exist.

A different approach could be to compare the contribution of different geochemical reservoirs to the CO2 emissions. To do so, it is necessary to investigate the different origins of CO2 in the diffuse emissions by analyzing the isotopic composition of the carbon in the soil CO2. The addition of deep-seated CO2 (which includes mantle-derived CO2 and metamorphism of marine carbonate rocks) causes a graphical trend of samples along the arrows shown in Figure 7, towards δ13C (CO2) > −8‰ vs. VPDB (Javoy et al. 1978; Barnes et al. 1988) and [CO2] ~ 100%. São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands showed different degrees of atmospheric and biogenic CO2 contributions. Only Brava and Fogo islands showed an endogenous CO2 contribution with δ13C (CO2) values higher than those representative of a volcanic-hydrothermal source (Camarda et al. 2007). According to D’Alessandro and Parello (1997), δ13C (CO2) values between −1‰ and 1‰ may be subjected to isotopic fractionation due to diffusion processes and/or interaction with thermal aquifers. Since the carbon isotopic composition of the CO2 discharged from fumaroles at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo is well constrained, this isotopic composition can be assumed as representative of deep-seated CO2 (range from −4.5‰ to −4.1‰ with a mean of −4.2‰; ±0.1‰; Dionis et al. 2014). However, just comparing the behavior depicted by δ13C (CO2) vs. 1/[CO2] diagram at the three areas of study, it does not seem to be a conclusive model to establish a relationship with the level of volcanic activity, because despite both Fogo and Brava volcanic systems have different geological ages and eruptive records (Fogo is the only island with historical eruptions) they show important addition of deep-seated CO2 (Figure 7).

Finally, we considered to apply two geochemical tools such as the ratio of peak/background mean values, directly related to diffuse CO2 degassing, and the magmatic helium emission as the 3He/4He isotopic ratios at São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands. 3He/4He isotopic in terrestrial fluids is the most powerful geochemical parameter to detect a mantle source (Sano et al. 1984; Sano and Fischer 2013b). Figure 8 shows the relation between the peak and background diffuse CO2 efflux mean values ratio for each volcanic system and the helium-3 emission from Brava and Fogo Islands. Since samples for helium isotopic analysis, either gas emanations or groundwater, were not available at São Vicente to perform helium isotopic analysis, we have assumed for São Vicente the values measured at Santo Antão and São Nicolau islands by Heilweil et al. (2009) (0.9 to 3.4 Ra; 3He/4He). This assumption is supported by its geographical proximity and similar geological ages (Ancochea et al. 2010; Ramalho, 2011). The horizontal segment represents the minimum and maximum 3He/4He ratio measured by Heilweil et al. (2009), in the case of Santo Antão and São Nicolau (assumed to be similar for São Vicente) and this work for Fogo and Brava islands. The points represented the average of those values. Figure 8 shows a very good correlation between peak/background ratio and the helium-3 emission for São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo islands, as well as a good agreement with the geological ages of the three islands, directly related to the level of volcanic activity. Youngest sub-aerial volcanic rocks at São Vicente Island have a minimum age of 0.33 Ma (Pleistocene; Ancochea et al. 2010), whereas Brava Island likely has shown Holocene volcanism (Madeira et al. 2010). Unlike these two islands, Fogo is one of the most active volcanic islands in the world, with almost 30 historical eruptions since the beginning of European settlement around approximately 1,500 AD (Ribeiro 1960), the latest one taking place in 2014. The highest observed 3He/4He ratios were measured at the fumarolic discharges at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo are equivalent to the canonical 3He/4He isotopic ratio range accepted for MORB-derived fluids (8 ± 1 Ra; Craig and Lupton 1976; Kurz and Jenkins 1981; Lupton 1983), and these values are observed in others similar volcanic systems as Canary Islands (7.21 Ra (fumaroles discharge at Teide volcano); Pérez et al. 1996). This spatial distribution together with the observed differences between peak/background ratios seems to be in a very good agreement with the geological age of the islands and, therefore with the stage of the volcanic activity in Cape Verde. However, further studies at other volcanic oceanic islands will be required to better understand the importance using these geochemical tools.

Relationship between soil CO 2 efflux peak values (×background) and the average 3 He/ 4 He ratio from Cape Verde archipelago. Horizontal bars represents the minimum and maximum 3He/4He ratio measured by Heilweil et al. (2009), in the case of San Antão and São Nicolau (assumed to be similar for São Vicente) and this work for Fogo and Brava islands.

Conclusions

This study present the first diffuse CO2 degassing results in Cape Verde islands and its relationship with volcanic activity. The purely endogenous emission values (peak populations) measured in the three studied volcanic systems, São Vicente, Brava, and Fogo Islands, expressed as times the background values, seem to be directly related to the magmatic helium emission as 3He/4He isotopic ratios and therefore, to the present magmatic degassing and volcanic activity in Cape Verde. This statement is also supported by the relative geological ages of the eruptive activities occurred at the three islands. The summit crater of Pico do Fogo showed the maximum diffuse CO2 efflux and the highest 3He/4He ratios of Cape Verde and is the only area showing fumarolic discharges in the archipelago. In addition, Fogo is the only Cape Verdean island with eruptive activity in historical times (<500 years). Although Brava island has shown an important recent seismic activity (Heleno da Silva et al. 2006) and obvious endogenous CO2 emissions in specific areas (Baleia and Vinagre), it has not experienced historical eruptive activity and shows lower magmatic helium degassing values than Fogo. Finally, São Vicente, without Holocene eruptions, has shown the lower endogenous emission values.

Therefore, the above observations strongly indicate that diffuse CO2 degassing is clearly linked to the level of volcanic activity and can be used as a useful geochemical tool for volcano monitoring programs in Cape Verde. To perform discrete CO2 efflux surveys with a periodicity equivalent to the volcanic activity degree will provide important information about future episodes of volcanic unrest: higher at Fogo (mainly at the summit crater of Pico do Fogo), lesser at Brava and the lower at São Vicente islands.

References

Allard P, Carbonelle J, Dajlevic D, Le Bronec J, Morel P, Robe MC, Maurenas JM, Faivre-Pierret R, Martins D, Sabroux JC, Zettwoog P (1991) Eruptive and diffuse emissions of CO2 from Mount Etna. Nature 351:387–391

Ancochea E, Huertas MJ, Hernán F, Brändle JL (2010) Volcanic evolution of São Vicente, Cape Verde Islands: the Praia Grande landslide. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 198:143–157, doi:1016/j.jvolgeores.2010.08.016

Arpa MC, Hernández P, Padrón E, Reniva P, Padilla GD, Bariso E, Melián G, Barrancos J, Nolasco D, Calvo D, Pérez NM, Solidum RU Jr (2013) Geochemical evidence of magma intrusion at Taal volcano, Philippines, in 2010-2011 from diffuse carbon dioxide emissions. Bull Volcanol 75:747, doi:10.1007/s00445-013-0747-9

Barnes I, Evans WC, White D (1988) The role of mantle CO2 in volcanism. Appl Geochem 3:281–285

Baubron JC, Allard P, Toutain JP (1990) Diffuse volcanic emissions of carbon dioxide from Vulcano Island, (Italy). Nature 344:51–53

Brochmann C, Rustan OH, Lobin W, Kilian N (1997) The endemic vascular plants of the Cape Verde Islands, W Africa. Sommerfeltia 24:1–356

Burton MR, Sawyer GM, Granieri D (2013) Deep carbon emissions from volcanoes: carbon in Earth. Rev Min Geochem 75:323–354, doi:10.2138/rmg.2013.75.11

Camarda M, De Gregorio S, Favara R, Gurrieri S (2007) Evaluation of carbon isotope fractionation of soil CO2 under an advective-diffusive regimen: a tool for computing the isotopic composition of unfractionated deep source. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 71:3016–3027

Carapezza ML, Inguaggiato S, Brusca L, Longo M (2004) Geochemical precursors of the activity of an open-conduit volcano: the Stromboli 2002-2003 eruptive events. Geophys Res Lett. doi:101029/2004GL019614

Carapezza ML, Barberi F, Ranaldi M, Ricci T, Tarchini L, Barrancos J, Fischer C, Perez N, Weber K, Di Piazza A, Gattuso A (2012) Diffuse CO2 soil degassing and CO2 and H2S concentrations in air and related hazards at Vulcano Island (Aeolian arc, Italy). J Volcanol Geotherm Res. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.06.010

Cardellini G, Chiodini G, Frondini F (2003) Application of stochastic simulation to CO2 flux from soil: mapping and quantification of gas release. J Geophys Res 108(B9):2156–2202, doi:101029/2002JB002165

Cerling TE, Solomon DK, Quade J, Bowman JR (1991) On the isotopic composition of carbon in soil carbon dioxide. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 55:3403–3405

Chiodini G, Frondini F, Raco B (1996) Diffuse emission of CO2 from the Fossa crater Vulcano Island (Italy). Bull Volcanol 58:41–50

Chiodini G, Cioni R, Guidi M, Raco B, Marini L (1998) Soil CO2 flux measurements in volcanic and geothermal areas. Appl Geochem 13:543–552

Chiodini G, Frondini F, Cardellini C, Granieri D, Marini L, Ventura G (2001) CO2 degassing and energy release at Solfatara volcano, Campi Flegrei, Italy. J Geophys Res 106(B8):16213–16221

Chiodini G, Caliro S, Cardellini C, Avino R, Granieri D, Schmidt A (2008) Carbon isotopic composition of soil CO2 efflux, a powerful method to discriminate different sources feeding soil CO2 degassing in volcanic-hydrothermal areas. Earth Plan Sci Lett 274:372–379

Courtney RC, White RS (1986) Anomalous heat flow and geoid across the Cape Verde Rise: evidence for dynamic support from a thermal plume in the mantle. Geophys J Roy Astron Soc 87:815–867

Craig H (1953) The geochemistry of the stable carbon isotope. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 3:53–92

Craig H, Lupton JE (1976) Primordial neon, helium and hydrogen in oceanic basalts. Earth Planet Sci Lett 31:369–385

Craig H, Lupton JE, Horibe Y (1978) A Mantle Helium Component in Circum Pacific Volcanic Gases: Hakone, The Marianas, and Mt. Lassen. In: Alexander EC, Ozima M (eds) Terrestrial Rare Gases. Scientifi c Societies Press, Tokyo, Japan, pp 3–16

D'Alessandro W, Parello F (1997) Soil gas prospection of He, 222Rn and CO2: Vulcano Porto area, Aeolian Islands, Italy. Appl Geochem 12:213–224

Day SJ, da Silva SIN H, Fonseca JFBD (1999) A past giant lateral collapse and present-day flank instability of Fogo, Cape Verde Islands. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 94:191–218, doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00103-1

De Gregorio S, Camarda M, Gurrieri S, Favara R (2014) Change in magma supply dynamics identified in observations of soil CO2 emissions in the summit area of Mt. Etna Bull Volcanol 76:846, doi:10.1007/s00445-014-0846-2

Deutsch C, Journel A (1998) GSLIB: Geostatistical Software Library 740 and Users Guide, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Dionis SM, Melián G, Rodríguez F, Hernández PA, Padrón E, Pérez NM, Barrancos J, Padilla G, Sumino H, Fernandes P, Bandomo Z, Silva S, Pereira JM, Semedo H (2014) Diffuse volcanic gas emission and thermal energy release from summit crater of Pico do Fogo, Cape Verde. Bull Volcanol. doi:10.1007/s00445-014-0897-4

Duprat HI, Friis J, Holm PM, Grandvuinet T, Sørensen RV (2007) The volcanic and geochemical development of São Nicolau, Cape Verde Islands: Constraints from field and 40Ar/39 Ar evidence. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 162:1–19

Faria B, Fonseca JBD (2014) Investigating volcanic hazard in Cape Verde Islands through geophysical monitoring: network description and first results. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 14:485–499, doi:10.5194/nhess-14-485-2014

Foeken JPT, Day S, Stuart FM (2009) Cosmogenic 3He exposure dating of the Quaternary basalts from Fogo, Cape Verdes: implications for rift zone and magmatic reorganisation. Quat Geochronol 4:37–49

Frondini F, Chiodini G, Caliro S, Cardellini C, Granieri D, Ventura G (2004) Diffuse CO2 degassing at Vesuvio, Italy. Bull Volcanol 66:642–651

Gerlach TM (1986) Exsolution of H2O, CO2, and S during eruptive episodes at Kilauea volcano, Hawaii. J Geophy Res. doi:10.1029/JB080i012p12177

Gerlach TM, Doukas MP, McGee KA, Kessler R (2001) Soil flux and total emission rates of magmatic CO2 at the Horeshoe Lake tree kill, Mammoth Mountain, California, 1995-1999. Chem Geol 177:101–116

Granieri D, Carapezza ML, Chiodini G, Avino R, Caliro S, Ranaldi M, Ricci T, Tarchini L (2006) Correlated increase in CO2 fumarolic content and diffuse emission from La Fossa crater (Vulcano, Italy): evidence of volcanic unrest or increasing gas release from a stationary deep magma body? Geophys Res Lett 33:L13316, doi:101029/2006GL026460

Hards VL (2005) Volcanic contributions to the global carbon cycle. British Geological Survey 10:26

Heilweil VM, Kip Solomon D, Gingerich SB, Verstraeten IM (2009) Oxygen, hydrogen and helium isotopes for investigating groundwater systems of Cape Verde Islands, West Africa. Hydrogeol J 17:1157–1174

Heleno da Silva SIN, Day SJ, Fonseca JFBD (1999) Fogo Volcano, Cape Verde Islands: seismicity-derived constraints on the mechanism of the 1995 eruption. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 94(1–4):219–231

Heleno da Silva SIN, Faria BVE, Bandomo Z, Fonseca JFBD (2006) Observations of high-frequency harmonic tremor in Fogo, Cape Verde Islands. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 158:361–379

Hernández PA, Pérez NM, Salazar JM, Nakai S, Notsu K, Wakita H (1998) Diffuse emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and hellium-3 from Teide volcano, Tenerife, Canary Islands. Geophys Res Lett 25:3311–3314

Hernández PA, Notsu K, Salazar JM, Mori T, Natale G, Okada H, Virgili G, Shimoike Y, Sato M, Pérez NM (2001a) Carbon dioxide degassing by advective flow from Usu volcano, Japan. Science 292:83–86

Hernández PA, Salazar JM, Shimoike Y, Mori T, Notsu K, Perez NM (2001b) Diffuse emission of CO2 from Miyakejima volcano, Japan. Chem Geol 177:175–185

Hernández PA, Notsu K, Tsurumi M, Mori T, Ohno M, Shimoike Y, Salazar JM, Pérez NM (2003) Carbon dioxide emissions from soils at Hakkoda, North Japan. J Geophys Res 108:6–1–6–10

Hernández PA, Padilla G, Padrón E, Pérez NM, Calvo D, Nolasco D, Melián G, Barrancos J, Dionis S, Rodríguez F, Sumino H (2012a) Analysis of long- and short-term temporal variations of the diffuse CO2 emission from Timanfaya volcano, Lanzarote, Canary Islands. Appl Geochem 27(12):2486–2499, doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2012.08.008

Hernández PA, Pérez NM, Fridriksson T, Egbert J, Ilyinskaya E, Thárhallsson A, Ivarsson G, Gíslason G, Gunnarsson I, Jónsson B, Padrón E, Melián G, Mori T, Notsu K (2012b) Diffuse volcanic degassing and thermal energy release from Hengill volcanic system, Iceland. Bull Volcanol 74(10):2435–2448, doi:10.1007/s00445-012-0673-2

Hinkle M, Kilburn J (1979) The use of vacutainer tube for collection of soil samples for helium analysis US Geological Suvey Open File Rep, 7th edn., p 1441

Holm PM, Wilson JR, Christensen BP, Hansen L, Hansen SL, Hein KM, Mortensen AK, Pedersen R, Plesner S, Runge MK (2006) Sampling the Cape Verde mantle plume: evolution of melt compositions on Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands. J Petrol 47:145–189, doi:10.1093/petrology/egi071

Holm P, Grandvuinet T, Friis J, Wilson J, Barke A, Plesner S (2008) An 40Ar-39Ar study of the Cape Verde hot spot: temporal evolution in a semistationary plate environment. J Geophys Res 113(B8). doi:10.1029/2007JB005339

Javoy M, Pineau F, Liyama I (1978) Experimental determination of the isotopic fractionation between gaseous CO2 and carbon dissolved in tholeitic magma. Contrib Mineral Petr 67:35–39, doi:10.1007/BFO0371631

Jørgensen J, Holm P (2002) Temporal variation and carbonatite contamination in primitive ocean island volcanics from São Vicente, Cape Verde Islands. Chem Geol 192(3–4):249–267

Kurz MD, Jenkins WJ (1981) The distribution of helium in oceanic basalt glasses. Earth Planet Sci Lett 53:41–54

Liuzzo M, Gurrieri S, Giudice G, Giuffrida G (2013) Ten years of soil CO2 continuous monitoring on Mt. Etna: exploring the relationship between processes of soil degassing and volcanic activity. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 14:2886–2899, doi:10.1002/ggge.20196

Lobin W, Zizka G (1987) Einteilung der Flora (Phanerogamae) der Kapverdischen Inseln nach ihrer Einwanderungsgeschichte Courier Forschungsinst. Senckenberg 95:127–153

Lodge A, Helffrich G (2006) Depleted swell root beneath the Cape Verde Islands. Geology 34:449–452

Lupton JE (1983) Terrestrial inert gases: isotope tracer studies and clues to primordial components in the mantle. Ann Rev Earth Planet Sci 11:371–414

Machado F (1965) Mechanism of Fogo volcano, Cape Verde Islands. Garcia de Orta Lisboa 13:51–56

Madeira J, Mata J, Mourão C, Brum da Silveira A, Martins S, Ramalho R, Hoffmann DJ (2010) Volcano-stratigraphic and structural evolution of Brava Island (Cape Verde) based on 40Ar/ 39Ar, U-Th and field constraints. J Volcan Geotherm Res 196(3):219–235

Matsuda J, Matsumoto T, Sumino H, Nagao K, Yamamoto J, Miura Y, Kaneoka I, Takahata N, Sano Y (2002) The 3He/4He ratio of the new internal He standard of Japan (HESJ). Geophys J Roy Astron Soc 36:191–195

Melián G, Padilla G, Calvo D, Pérez N, Hernández P, Barrancos J, Fuentes W, Cabral J, Mota Gomes, Bandomo Z, Melo S, Barros I (2008) Monitorización geoquímica de la emisión difusa de CO2 por el volcán Fogo, Cabo Verde. Aportaciones recientes en volcanología 2005–2008, Ed: Elena González Cárdenas, Estela Escobar Lahoz, Rafael Becerra Ramírez, Rafael Ubaldo, Gosálvez Rey y Javier DónizPáez. Centro de Estudios Calatravos. ISBN: 978-84-614-1025-5

Melián G, Hernández PA, Padrón E, Pérez NM, Barrancos J, Dionis S, Padilla G, Rodríguez S, Calvo D, Nolasco D (2014) Spatial and temporal variations of diffuse CO2 degassing at El Hierro volcanic system: relation to the 2011-2012 submarine eruption. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 119:6976–6991, doi:10.1002/2014JB011013

Mitchell JG, Le Bas MJ, Zielonka J, Furnes H (1983) On dating the magmatism of Maio, Cape Verde Islands. Earth Planet Sci Lett 64:61–76

Navarro JM (1999) Map volcano structural of Fogo Island. Internal report. Institute Technologic and Renewable Energy, Islas Canarias, Spain

Notsu K, Mori T, Chanchah Do Vale S, Kagi H, Ito T (2006) Monitoring quiescent volcanoes by diffuse CO2 degassing: case study of Mt. Fuji, Japan. Pure App Geophys 163:825–835

Olehowski C, Naumann S, Fischer D, Siegmund A (2008) Geo-ecological spatial pattern analysis of the island of Fogo (Cape Verde). Global Planet Change 64:188–197

Padilla G, Hernández P, Pérez NM, Pereda E, Padrón E, Melián G, Barrancos J, Rodríguez F, Dionis S, Calvo D, Herrera M, Strauch W, Muñoz A (2014) Anomalous diffuse CO2 emissions at the Masaya Volcano (Nicaragua) related to seismic-volcanic unrest. Pure Appl Geophys 171:1–14, doi:10.1007/s00024-013-0756-9

Padrón E, Melián G, Nolasco D, Barrancos J, Hernández PA, Pérez N (2008) Precursory diffuse carbon dioxide degassing related to seismic activity in El Hierro islands, Canary Islands, Spain. Pure App Geophys 165:95–114

Padrón E, Hernández PA, Pérez NM, Toulkeridis T, Melián G, Barrancos J, Virgili G, Sumino H, Notsu K (2012) Fumarole/plume and diffuse CO2 emission from Sierra Negra caldera, Galapagos archipelago. Bull Volcanol 74(6):1509–1519, doi:10.1007/s00445-012-0610-4

Padrón E, Pérez N, Hernández PA, Sumino H, Melián G, Barrancos J, Nolasco D, Padilla G, Dionis S, Rodríguez F, Hernández I, Calvo D, Peraza MD, Nagao K (2013) Diffusive helium emissions as a precursory sign of volcanic unrest. Geology 41(5):539–542

Padrón E, Pérez NM, Melián G, Hernández PA, Sumino H, Padilla G, Barrancos J, Dionis S, Rodríguez F, Notsu K, Calvo D (2015) Dynamics of diffuse carbon dioxide emission from Cumbre Vieja volcano, La Palma, Canary Islands. Bull Volcanol, doi 10.1007/s00445-015-0914-2

Parkinson KJ (1981) An improved method for measuring soil respiration in the field. J Appl Ecol 18:221–228

Pérez NM, Nakai S, Wakita H, Hernández PA, Salazar JML (1996) Helium-3 emission in and around Teide volcano, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain. Geophys Res Lett 23:3531–3534

Pérez NM, Salazar JML, Hernández PA, Soriano T, Lopez K, Notsu K (2004) Diffuse CO2 and 222Rn degassing from San Salvador volcano, El Salvador, Central America. Bull Geol Soc Am 375:227–236

Pérez NM, Hernández PA, Padrón E, Cartagena R, Olmos R, Barahona F, Melián G, Salazar P, López DL (2006) Anomalous diffuse CO2 emission prior to the January 2002 short-term unrest at San Miguel Volcano, El Salvador, Central America. Pure App Geophys 4:883–896, doi:101007/s00024-006-0050-1

Pérez NM, Hernández PA, Padilla G, Nolasco D, Barrancos J, Melián G, Padrón E, Dionis S, Calvo D, Rodríguez F, Notsu M, Mori T, Kusakabe M, Arpa MC, Reniva P, Ibarra M (2011) Global CO2 emission from volcanic lakes. Geology 39(3):235–238, doi:10.1130/G31586.1

Pérez NM, Padilla GD, Padrón E, Hernández PA, Melián GV, Barrancos J, Dionis S, Nolasco D, Rodríguez F, Calvo D, Hernández I (2012) Precursory diffuse CO2 and H2S emission signatures of the 2011-2012 El Hierro submarine eruption, Canary Islands. Geophys Res Lett. doi:10.1029/2012GL052410

Pérez N, Hernández P, Padrón E, Melián G, Nolasco D, Barrancos J, Padilla G, Calvo D, Rodríguez F, Dionis S, Chiodini G (2013) An increasing trend of diffuse CO2 emission from Teide volcano (Tenerife, Canary Islands): geochemical evidence of magma degassing episodes. J Geolog Soc London. doi:10.1144/jgs2012-125

Plesner S, Holm PM, Wilson JR (2002) 40Ar-36Ar geochronology of Santo Antão, Cape Verde Islands. J Volcan Geotherm Res 120:103–121

Ramalho RAS (2011) Building the Cape Verde Islands. Springer Theses, Berlin Heidelberg, p 207

Ribeiro O (1960) A Ilha do Fogo e as suas erupcoes, 2nd Memorias, seriegeografica I. Publ. Junta de Investigacoes do Ultramar, Ministerio do Ultramar, Lisbon, Portugal (in Portuguese)

Rogie JD, Kerrick DM, Sorey ML, Chiodini G, Galloway DL (2001) Dynamics of carbon dioxide emission at Mammoth Mountain, California. Earth Plan Sci Lett 188:535–541

Salazar JML, Hernández PA, Pérez NM, Melián G, Álvarez J, Segura F, Notsu K (2001) Diffuse emissions of carbon dioxide from Cerro Negro volcano, Nicaragua, Central America. Geophys Res Lett 28:4275–4278

Salazar JM, Pérez NM, Hernández PA, Soriano T, Barahona F, Olmos R, Cartagena R, López DL, Lima N, Melián G, Padrón E, Galindo I, Notsu K (2002) Precursory diffuse carbon dioxide degassing signatures of recent earthquakes in El Salvador, Central America. Earth Planet Sci Lett 205(1–2):81–89

Sano Y, Fischer T (2013) The Analysis and Interpretation of Noble Gases in Modern Hydrothermal Systems. In: Burnard P (ed) The Noble Gases as Geochemical Tracers. Springer-Verlag Advances in Isotope Geochemistry, New York, pp 249–317

Sano Y, Nakamura Y, Wakita H, Urabe A, Tominaga T (1984) Helium-3 emission related to volcanic activity. Science 224:150–151, doi:10.1126/science.224.4645.150

Sano Y, Marty B, Burnard P (2013) Noble Gases in the Atmosphere. In: Burnard P (ed) The Noble Gases as Geochemical Tracers. Springer-Verlag Advances in Isotope Geochemistry, New York, pp 17–32

Semedo JM, Brito A (1995) Nossa Terra Nossa Gente Programa Regional de Formação e Informação para o Ambiente (PFIE) Praia. Verde, Cabo (in portuguese)

Silva S, Monteiro S, Bandomo Z, Fernandes P, Andrade M, Fonseca J, Dionis S, Melián G, Nolasco D, Padilla G, Padrón E, Calvo D, Rodríguez F, Barros I, Rodrigues J, Gonçalves A, Barbosa A, Hernández P, Pérez N (2011) Geochemical Monitoring of Fogo Volcano, Cape Verde Abstract Teneguía Workshop-MAKAVOL 2011, La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain

Silva S, Cardoso N, Alfama V, Cabral J, Semedo H, Pérez NM, Dionis S, Hernández PA, Barrancos J, Melián G, Pereira JM, Rodríguez F (2015) Chronology of the 2014 Volcanic Eruption on the Island of Fogo, Cape Verde. Geophysical Research Abstracts EGU General Assembly, Vienna, Austria

Sinclair AJ (1974) Selection of thresholds in geochemical data using probability graphs. J Geochem Explor 3:129–149

Sumino H, Nagao K, Notsu K (2001) Highly sensitive and precise measurement of helium isotopes using a mass spectrometer with double collector system. J Mass Spectrom Soc Jpn 49:61–68

Torres PC, Silva LC, Mendes MH, Serralheiro A, Madeira J, Brum da Silveira A, Mota Gomes A (1997) Cronologia da erupcao vulcanica de 1995 na Ilha do Fogo, Cabo Verde. A erupcao vulcanica de 1995 na Ilha do Fogo, Cabo Verde. Publ. IICT, Lisboa., pp 133–144

Torres PC, Madeira J, Silva LC, Brum da Silveira A, Serralheiro A, Mota Gomes A (1998) Cartageológica da ilha do Fogo (República de Cabo Verde): erupções históricas e formações enquadrantes. In: Laboratório de Tecnofísica e Tectónica Experimental (LATTEX) (ed) University of Lisbon, 1 sheet at the 1:25.000 scale (in Portuguese)

Vinnik L, Silveira G, Kiselev S, Farra V, Webber M, Stutzmann E (2012) Cape Verde hot spot from the upper crust to the top of the lower mantle. Earth Plan Sci Lett 259:319–320, doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.12.017

Williams-Jones G, Stix J, Heiligmanm M, Chadand A, Sherwood Lollar B, Amer N, Garzon G, Barquero J, Fernandez E (2000) A model of diffuse degassing at three subduction-related volcanoes. Bull Volcanol 62:130–142

Acknowledgements

This work has been partially funded by the projects (i) MAKAVOL (MAC/3/C161) of the European Union Transnational Cooperation Programme MAC 2007-2013; (ii) CABOVERDE (08-CAP2-1202) of the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development, AECID; and (iii) UNICV of the Servicio de Acción Exterior del Cabildo Insular de Tenerife (Canary Island, Spain). We are also grateful to José Antonio Fernandes ‘Madjer’, António Gonçalves, Inocencio Barros, Dácil Nolasco, Isabel Gómez, Silvia Monteiro, Felipe Brito, Marcos Freitas Santos (SNPC-Mindelo), Joao Feliberto Semedo, and Judite Nascimento for their logistical support during the field work related to this research, as well as to Giovanni Chiodini and the anonymous reviewer whose useful comments and constructive suggestions greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NMP and PAH conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. GM, FR, ZB, SMD, and EP participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. SMD wrote the first version of manuscript. GM, FR, GDP, JB, and PF collected data. HSu performed the 3He/4He analyses. SS, JMP, HSe, and JC are participating investigators. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dionis, S.M., Pérez, N.M., Hernández, P.A. et al. Diffuse CO2 degassing and volcanic activity at Cape Verde islands, West Africa. Earth Planet Sp 67, 48 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-015-0219-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-015-0219-x