Abstract

Background

Patient–ventilator asynchrony (PVA) is a common problem in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) in the intensive care unit (ICU), and may accelerate lung injury and diaphragm mis-contraction. The impact of PVA on clinical outcomes has not been systematically evaluated. Effective interventions (except for closed-loop ventilation) for reducing PVA are not well established.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the impact of PVA on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing MV (Part A) and the effectiveness of interventions for patients undergoing MV except for closed-loop ventilation (Part B). We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, ClinicalTrials.gov, and WHO-ICTRP until August 2020. In Part A, we defined asynchrony index (AI) ≥ 10 or ineffective triggering index (ITI) ≥ 10 as high PVA. We compared patients having high PVA with those having low PVA.

Results

Eight studies in Part A and eight trials in Part B fulfilled the eligibility criteria. In Part A, five studies were related to the AI and three studies were related to the ITI. High PVA may be associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation (mean difference, 5.16 days; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.38 to 7.94; n = 8; certainty of evidence [CoE], low), higher ICU mortality (odds ratio [OR], 2.73; 95% CI 1.76 to 4.24; n = 6; CoE, low), and higher hospital mortality (OR, 1.94; 95% CI 1.14 to 3.30; n = 5; CoE, low). In Part B, interventions involving MV mode, tidal volume, and pressure-support level were associated with reduced PVA. Sedation protocol, sedation depth, and sedation with dexmedetomidine rather than propofol were also associated with reduced PVA.

Conclusions

PVA may be associated with longer MV duration, higher ICU mortality, and higher hospital mortality. Physicians may consider monitoring PVA and adjusting ventilator settings and sedatives to reduce PVA. Further studies with adjustment for confounding factors are warranted to determine the impact of PVA on clinical outcomes.

Trial registration protocols.io (URL: https://www.protocols.io/view/the-impact-of-patient-ventilator-asynchrony-in-adu-bsqtndwn, 08/27/2020).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient–ventilator asynchrony (PVA) is defined as a mismatch between the breathing efforts of a patient and breath delivery by a ventilator [1]. It is a common problem in mechanically ventilated patients and has an incidence of up to 80% [2]. PVA may cause ventilator-induced lung injury due to excessive tidal volume [3, 4], and diaphragm injury from eccentric contractions [5], both of which can affect clinical outcomes.

The impact of PVA in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation on clinical outcomes appears inconsistent among studies. Thille et al. reported that higher incidence of PVA was associated with a longer duration of mechanical ventilation, but was not associated with increased mortality [6]. Conversely, Blanch et al. found that patients with higher incidence of PVA had significantly higher ICU mortality than patients with lower incidence of PVA, while the duration of mechanical ventilation did not differ significantly between the two groups [7]. It also remains unclear whether PVA itself worsens clinical outcomes [8].

Recently, closed-loop ventilation systems such as neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA) and proportional assist ventilation (PAV) were shown to decrease the incidence of PVA during the weaning phase of mechanical ventilation in many trials [9, 10]. However, these ventilator modes cannot be utilized for all patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, because they are only available in limited numbers of ventilator systems. Other respiratory management procedures such as adjustment of sedatives or ventilator settings are possibly effective for reducing PVA. Therefore, systematic summarizations of the interventions for PVA are needed to improve the clinical outcomes of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation.

We addressed two research questions in this systematic review and meta-analysis. In Part A, we addressed the impact of PVA on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation. In Part B, we addressed the impact of interventions except closed-loop ventilation in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation on PVA.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11] (Additional file 1). Our protocol was registered in protocols.io (https://www.protocols.io/view/the-impact-of-patient-ventilator-asynchrony-in-adu-bsqtndwn).

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

The studies had to include adult patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation. In Part A, we defined an asynchrony index (AI) ≥ 10 or ineffective triggering index (ITI) ≥ 10 as high PVA. AI was defined as the number of asynchronous breaths, divided by the total number of breaths (both requested and delivered) multiplied by 100 [12]. ITI was defined as the number of ineffectively triggered breaths divided by the total number of triggered and ineffectively triggered breaths multiplied by 100 [13]. The counts of asynchronous breaths were set according to each study. We compared patients having high PVA with those having low PVA. We included published and unpublished observational studies, as well as secondary analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising cross-over trials, cluster-randomized trials, and quasi-randomized trials. In Part B, we assessed the effectiveness of patient management procedures for PVA on clinical outcomes including reduced PVA. We included published and unpublished interventional studies, as well as RCTs comprising cross-over trials, cluster-randomized trials, and quasi-randomized trials.

In Part A, we excluded studies involving patients who were only post-surgery, suspected of having bronchopleural fistulas or air leaks, and aged less than 18 years. In Part B, we excluded studies evaluating the effects of interventions of closed-loop ventilation systems, such as NAVA, PAV and SmartCare®.

Outcomes of interest

Part A. The primary outcomes were duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU mortality, and hospital mortality, and the secondary outcomes were incidence of reintubation and incidence of tracheostomy.

Part B. The primary outcomes were incidence of PVA and duration of mechanical ventilation, and the secondary outcomes were ICU mortality, hospital mortality, incidence of reintubation, and incidence of tracheostomy.

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), clinicaltrials.gov, and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Platform Search Portal (ICTRP) with no language restrictions for studies undertaken before 07 August 2020 (Additional file 2).

Study selection and data extraction

Two authors (MK and TS) independently assessed the remaining abstracts and, if necessary, their full-text articles to determine whether they satisfied the inclusion criteria. If two authors were unsure whether a study met the inclusion criteria, we contacted the study’s original authors and requested additional information. The two authors then compared their lists. Any differences in opinion were resolved by discussion or, if this failed, through arbitration by a third author (ST).

Quality assessment

Two authors (MK and TS) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study by using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool [14] in Part A, and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions (ROBINS-I) [15] and the Risk Of Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB2) [16] in Part B. Two authors assessed each domain by the confounding factors of age, severity score, and coexisting diseases (acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure). Any conflicts between the two authors were resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Data synthesis

All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan 5.4; Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) software. We used a random-effect model weighted by the inverse variance estimate. The effects for the continuous outcomes of duration of mechanical ventilation and AI were expressed as the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The effects for the dichotomous outcomes of mortality, incidence of reintubation, and incidence of tracheostomy were expressed as the odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. We converted medians and interquartile ranges to means and standard deviations using a method proposed by Wan et al. [17].

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

We added a subgroup analysis for the assessment of PVA represented as AI and ITI to planned subgroup analyses. We planned to carry out a sensitivity analysis for hospital mortality that was not clearly defined at a time point.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We calculated I2 as a measure of variation across studies that arose through heterogeneity rather than by chance, and interpreted the values as follows: 0%–40%, negligible heterogeneity; 30%–60%, mild-to-moderate heterogeneity; 50%–90%, moderate-to-substantial heterogeneity; 75%–100%, considerable heterogeneity. If heterogeneity was identified for an outcome (I2 > 50%), we investigated the underlying reasons and conduct a χ2 test, with a p value of < 0.10 considered to indicate statistical significance.

Assessment of publication bias

We searched the trial registers (World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Platform Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov) to identify completed, but unpublished, trials at the time of the review.

Summary of findings

In Part A, we created a summary-of-findings table that included an overall grading of the certainty of the evidence for each of the main outcomes, which was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [18].

Statements

We followed the informative statements regarding the manner in which to communicate the findings according to the GRADE guideline [19].

Results

Results of the search

We screened 1580 records, after removal of duplicates, and assessed the full-text articles of 25 studies for eligibility. Of these, eight studies [7, 12, 13, 20,21,22,23,24] in Part A and eight trials [6, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31] in Part B met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1, Additional file 3). The search did not reveal any ongoing and unpublished studies.

Part A (impact of PVA on clinical outcomes)

Characteristics of the studies included in the qualitative synthesis

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the eight included observational studies related to PVA, of which five studies were related to AI [7, 12, 21,22,23] and three studies were related to ITI [13, 20, 24]. According to the risk of bias in the included studies using the QUIPS tool, bias domain 6 (statistical analysis and reporting) was high in all studies except for hospital mortality in two studies (Additional file 4).

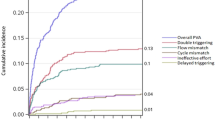

Results of the synthesis

The meta-analyses for the associations of PVA with the primary and secondary outcomes are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. Regarding the primary outcomes, high PVA may be associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation (MD, 5.16 days; 95% CI 2.38 to 7.94; n = 8; CoE, low), higher ICU mortality (OR, 2.73; 95% CI 1.76 to 4.24; n = 6; CoE, low), and higher hospital mortality (OR, 1.94; 95% CI 1.14 to 3.30; n = 5; CoE, low). Regarding the secondary outcomes, high PVA may be associated with higher incidence of reintubation (OR, 2.21; 95% CI 0.72 to 6.83; n = 4; CoE, low) and higher incidence of tracheostomy (OR, 2.13; 95% CI 0.96 to 4.71; n = 5; CoE, low).

Forest plots for ventilated patients with high patient–ventilator asynchrony (PVA) versus low PVA and clinical outcomes in Part A. A Duration of mechanical ventilation. B ICU mortality. C Hospital mortality. D Incidence of reintubation. E, Incidence of tracheostomy. PVA, patient–ventilator asynchrony; AI, asynchrony index; ITI, ineffective triggering index; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

We conducted the added and prescribed subgroup analysis for the index of PVA (AI/ITI) and the method (human/software) of PVA assessment (Fig. 2, Additional file 5). Regarding the primary outcomes, AI ≥ 10 may be associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation (MD, 3.18 days; 95% CI − 0.90 to 7.25; n = 5), higher ICU mortality (OR, 2.64; 95% CI 0.85 to 8.16; n = 3), and higher hospital mortality (OR, 1.89; 95% CI 0.97 to 3.70; n = 4). ITI ≥ 10 may be associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation (MD 6.92 days; 95% CI 3.53 to 10.31; n = 3), higher ICU mortality (OR, 3.03; 95% CI 1.76 to 5.22; n = 3), and higher hospital mortality (OR, 2.03; 95% CI 0.85 to 4.85; n = 2). Studies that focused on the duration of mechanical ventilation had a similar MD for the relationship between human and software assessments (human assessment: MD, 6.21 days; 95% CI 3.49 to 8.93 versus software assessment: MD, 2.30 days; 95% CI −3.76 to 8.35, P = 0.25). Studies that focused on ICU mortality and hospital mortality also had a similar OR for the relationship between human and software assessments (human assessment: OR, 2.96; 95% CI 1.67–5.23 compared to software assessment: OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.06–7.38, P = 0.92; human assessment: OR, 1.90; 95% CI 0.83–4.39 compared to software assessment: OR, 2.09; 95% CI 0.92–4.71, P = 0.88, respectively).

Difference between protocol and review

We did not perform predetermined subgroup analyses for the following variables due to insufficient data: causes of admission to ICU (internal diseases versus traumatic diseases), coexisting ARDS (ARDS versus non-ARDS), ventilator mode (assist control mode versus pressure-support ventilation), and timing (acute phase versus whole period of mechanical ventilation). We were also unable to perform the following planned sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes due to insufficient data: exclusion of studies (i) using imputed statistics; (ii) including timing when assessing of PVA was not only acute phase, but also outside the acute phase; (iii) including post-operative patients, and (iv) with high or moderate risk of bias, due to insufficient data.

Part B (interventions for reducing PVA)

Characteristic of the studies included in the qualitative synthesis

The characteristics of the eight included trials, of which four trials were related to ventilator settings [6, 28,29,30], three trials were related to sedation [25, 27, 31], and one trial was related to ventilator settings and sedation [26], are shown in Table 3. The risks of bias using the ROBINS-I and RoB2 tools are shown in Additional files 6, 7 and 8.

Summary of the results

Because of the variety of interventions for PVA, a meta-analysis was not performed. Among four trials that assessed the effect of adjusting ventilator settings to reduce PVA, two trials [28], 30 assessed the mode of mechanical ventilation, one trial [29] assessed the tidal volume, and one trial [6] assessed the pressure-support level and insufflation time during pressure-support ventilation (PSV). These trials showed application of the PSV mode compared with the pressure-control ventilation mode, higher tidal volume ventilation, and increased pressure-support level in PSV were significantly associated with reduced PVA in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation.

Three trials assessed the effect of sedation on reducing PVA. No sedation was associated with significantly lower AI than daily interruption of sedation [25]. In PSV, wakefulness and light sedation significantly decreased ITI compared with deep sedation to obtain a bispectral index value of 40 [31]. Regarding sedatives, mean AI was lower with dexmedetomidine than with propofol [27].

One trial compared the effects of the sedation–analgesia and changes in ventilator settings on AI [26]. The decrease in AI was greater after changing the ventilator settings than after increasing the sedation–analgesia.

Interventions for sedation and ventilator settings were consistent in their tendency to reduce PVA (Additional file 9).

Discussion

The results of the present review demonstrated that PVA, represented by AI or ITI ≥ 10, may be associated with hard outcomes including duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU mortality, and hospital mortality based on eight studies including 673 patients. Interventions for PVA, such as adjustment of sedation and ventilator settings, have the potential to reduce PVA.

The associations between PVA and longer duration of mechanical ventilation or higher mortality suggests that intensive care physicians may need to consider paying attention to PVA during management of patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation. The types of asynchrony reflected by the defined AI varies slightly among literatures, but mainly included ineffective triggering, double triggering, short cycling, and prolonged cycling. Ineffective triggering may be caused by increased intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, reduced respiratory drive, or decreased respiratory muscle strength [6, 32]. Double-triggered breaths were associated with the higher tidal volume [33], which is potentially harmful to patients on mechanical ventilation [34]. Therefore, it is very likely that a high incidence of PVA is associated with clinical outcomes. However, because the certainty of the evidence was low, mainly through a lack of adjustment for confounding factors, researchers need to perform studies with increased sample sizes and adjustment for confounding factors. Furthermore, it currently remains unknown which type of PVA has the greatest impact on the hard outcomes in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Moreover, reverse triggering, which has received much attention in recent years for its possible relevance to lung injury [35], was not included in many of the studies. Further research focusing on specific types of PVA including reverse triggering is needed to clarify the mechanism and impact of PVA on pulmonary pathophysiology.

To date, there is no definitive methodology for assessment of PVA. Although visual inspection of airway pressure and flow waveform is the most common approach, use of adjunctive signals such as EAdi and esophageal catheter greatly enhance the detection of PVA [36]. Software that utilizes automatic algorithms has similar power for detection of asynchronies to visual inspection expertise and EAdi signals [37]. In our subgroup analysis, the impact of PVA determined by human or software assessment on duration of mechanical ventilation and hospital mortality did not differ significantly. In the future, a standardized monitoring system that can detect PVA in real time and is easy to use in clinical and research settings will be needed.

Interventions, such as adjustment of ventilator settings and sedatives or analgesic drugs, have the potential to reduce PVA. Ventilator support needs to be adjusted to ensure that the patient’s inspiratory effort is adequate, because excessive ventilator support induces ineffective triggering through diaphragm atrophy and under assistance may result in double triggering by strong inspiratory efforts [38]. Similarly, sedatives and analgesics substantially affect the respiratory drive and PVA [2, 31, 39]. The use of dexmedetomidine and light sedation may be useful to prevent suppression of the respiratory effort, which may lead to diaphragm atrophy. Therefore, it is important to adjust the ventilator settings and sedatives while careful assessment of the patient’s inspiratory effort. Regarding the research on interventions for PVA, since there is a limited number of studies related to clinical outcomes, and thus researchers may need to consider performing more RCTs for interventions to reduce PVA and improve clinical outcomes.

The present review has several strengths. It is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effect of PVA on hard outcomes and interventions for PVA. We performed this rigorous review according to a predefined protocol using the PRISMA statement and GRADE approach. The present review also has some limitations. First, in Part A, the certainty of the evidence for all outcomes was low. Information on the associations between PVA and clinical outcomes after adjustment for confounding factors will help to clarify the impact of PVA on clinical outcomes. Second, we defined asynchrony index (AI) ≥ 10 or ineffective triggering index (ITI) ≥ 10 as high PVA. Patients in studies evaluating ITI might have various AI. However, the subgroup analysis for AI and ITI showed similar results. Third, we could not carry out several planned subgroup analyses because of the limited data. Fourth, in Part B, because of the variety and small number of interventions for PVA, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Conclusions

PVA may be associated with clinical outcomes. Intensive care physicians may need to pay greater attention to PVA during the management of patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, and the potential of adjustments to ventilator settings and sedatives to reduce PVA. Future studies with larger sample sizes, adjustment for confounding factors, and focus on specific types of PVA are warranted to determine the impact of PVA on clinical outcomes. Further RCTs are also needed to clarify the effective interventions for reducing PVA.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Asynchrony index

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CoE:

-

Certainty of evidence

- GRADE:

-

Grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ITI:

-

Ineffective triggering index

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- NAVA:

-

Neurally adjusted ventilatory assist

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PAV:

-

Proportional assist ventilation

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- PSV:

-

Pressure-support ventilation

- PVA:

-

Patient–ventilator asynchrony

- QUIPS:

-

Quality in Prognosis Studies

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- RoB2:

-

Risk of Bias tool for randomized trials

- ROBINS-I:

-

Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions

References

Gilstrap D, MacIntyre N. Patient-ventilator interactions. Implications for clinical management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1058–68.

de Wit M, Pedram S, Best AM, Epstein SK. Observational study of patient-ventilator asynchrony and relationship to sedation level. J Crit Care. 2009;24:74–80.

Beitler JR, Sands SA, Loring SH, Owens RL, Malhotra A, Spragg RG, et al. Quantifying unintended exposure to high tidal volumes from breath stacking dyssynchrony in ARDS: the BREATHE criteria. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1427–36.

Pohlman MC, McCallister KE, Schweickert WD, Pohlman AS, Nigos CP, Krishnan JA, et al. Excessive tidal volume from breath stacking during lung-protective ventilation for acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3019–23.

Gea J, Zhu E, Galdiz JB, Comtois N, Salazkin I, Fiz JA, et al. Functional consequences of eccentric contractions of the diaphragm. Archivos de bronconeumologia. 2009;45:68–74.

Thille AW, Cabello B, Galia F, Lyazidi A, Brochard L. Reduction of patient-ventilator asynchrony by reducing tidal volume during pressure-support ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1477–86.

Blanch L, Villagra A, Sales B, Montanya J, Lucangelo U, Lujan M, et al. Asynchronies during mechanical ventilation are associated with mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:633–41.

Murias G, Lucangelo U, Blanch L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:53–9.

Pettenuzzo T, Aoyama H, Englesakis M, Tomlinson G, Fan E. Effect of neurally adjusted ventilatory assist on patient-ventilator interaction in mechanically ventilated adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e602–9.

Kataoka J, Kuriyama A, Norisue Y, Fujitani S. Proportional modes versus pressure support ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:123.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Thille AW, Rodriguez P, Cabello B, Lellouche F, Brochard L. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during assisted mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1515–22.

de Wit M, Miller KB, Green DA, Ostman HE, Gennings C, Epstein SK. Ineffective triggering predicts increased duration of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2740–5.

Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280–6.

Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135.

Foroutan F, Guyatt G, Zuk V, Vandvik PO, Alba AC, Mustafa R, et al. GRADE Guidelines 28: use of GRADE for the assessment of evidence about prognostic factors: rating certainty in identification of groups of patients with different absolute risks. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;121:62–70.

Santesso N, Glenton C, Dahm P, Garner P, Akl EA, Alper B, et al. GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;119:126–35.

Hassan A, Amr A, Mohamed A. The effect of the trigger variable on the ineffective triggering index in mechanically ventilated patients. J Am Sci. 2011;7:76–81.

Robinson BR, Blakeman TC, Toth P, Hanseman DJ, Mueller E, Branson RD. Patient-ventilator asynchrony in a traumatically injured population. Resp Care. 2013;58:1847–55.

Rolland-Debord C, Bureau C, Poitou T, Belin L, Clavel M, Perbet S, et al. Prevalence and prognosis impact of patient-ventilator asynchrony in early phase of weaning according to two detection methods. Anesthesiology. 2017;127:989–97.

Sousa MLA, Magrans R, Hayashi FK, Blanch L, Kacmarek RM, Ferreira JC. Predictors of asynchronies during assisted ventilation and its impact on clinical outcomes: the EPISYNC cohort study. J Crit Care. 2020;57:30–5.

Vaporidi K, Babalis D, Chytas A, Lilitsis E, Kondili E, Amargianitakis V, et al. Clusters of ineffective efforts during mechanical ventilation: impact on outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:184–91.

Bassuoni AS, Elgebaly AS, Eldabaa AA, Elhafz AA. Patient-ventilator asynchrony during daily interruption of sedation versus no sedation protocol. Anesthesia Essays Res. 2012;6:151–6.

Chanques G, Kress JP, Pohlman A, Patel S, Poston J, Jaber S, et al. Impact of ventilator adjustment and sedation-analgesia practices on severe asynchrony in patients ventilated in assist-control mode. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2177–87.

Conti G, Ranieri VM, Costa R, Garratt C, Wighton A, Spinazzola G, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine and propofol on patient-ventilator interaction in difficult-to-wean, mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective, open-label, randomised, multicentre study. Crit Care. 2016;20:206.

Doorduin J, Sinderby CA, Beck J, van der Hoeven JG, Heunks LM. Assisted ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: lung-distending pressure and patient-ventilator interaction. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:181–90.

Figueroa-Casas JB, Montoya R. Effect of tidal volume size and its delivery mode on patient-ventilator dyssynchrony. Ann Am Thoracic Society. 2016;13:2207–14.

Luo J, Wang MY, Liang BM, Yu H, Jiang FM, Wang T, et al. Initial synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation versus assist/control ventilation in treatment of moderate acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Thoracic Dis. 2015;7:2262–73.

Vaschetto R, Cammarota G, Colombo D, Longhini F, Grossi F, Giovanniello A, et al. Effects of propofol on patient-ventilator synchrony and interaction during pressure support ventilation and neurally adjusted ventilatory assist. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:74–82.

Appendini L, Purro A, Patessio A, Zanaboni S, Carone M, Spada E, et al. Partitioning of inspiratory muscle workload and pressure assistance in ventilator-dependent COPD patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1301–9.

Sottile PD, Albers D, Higgins C, McKeehan J, Moss MM. The association between ventilator dyssynchrony, delivered tidal volume, and sedation using a novel automated ventilator dyssynchrony detection algorithm. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e151–7.

Sousa M, Magrans R, Hayashi FK, Blanch L, Kacmarek RM, Ferreira JC. Clusters of double triggering impact clinical outcomes: insights from the EPIdemiology of patient-ventilator aSYNChrony (EPISYNC) Cohort Study. J Crit Care. 2020;57:30–5.

Yoshida T, Nakamura MAM, Morais CCA, Amato MBP, Kavanagh BP. Reverse triggering causes an injurious inflation pattern during mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:1096–9.

Bruni A, Garofalo E, Pelaia C, Messina A, Cammarota G, Murabito P, et al. Patient-ventilator asynchrony in adult critically ill patients. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2019;85:676–88.

Blanch L, Sales B, Montanya J, Lucangelo U, Garcia-Esquirol O, Villagra A, et al. Validation of the Better Care(R) system to detect ineffective efforts during expiration in mechanically ventilated patients: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:772–80.

Goligher EC, Jonkman AH, Dianti J, Vaporidi K, Beitler JR, Patel BK, et al. Clinical strategies for implementing lung and diaphragm-protective ventilation: avoiding insufficient and excessive effort. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2314–26.

Vaporidi K, Akoumianaki E, Telias I, Goligher EC, Brochard L, Georgopoulos D. Respiratory drive in critically ill patients pathophysiology and clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:20–32.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Mohammed Ahmed Hamad for providing us with additional information regarding their studies. We also thank Alison Sherwin, PhD, from Edanz Group (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers JP 18K16518 and JP 21K16591.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK, KH, ST and YK participated in the design of the study. MK, TS, ST and YK performed the systematic review. MK wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. ST and YK revised the manuscript. KH, SO and NS helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Additional file 2:

Search strategies.

Additional file 3:

Characteristics of the studies excluded from the qualitative and quantitative syntheses.

Additional file 4:

Risk of bias for each study by using the Quality In Prognosis Studies tool in Part A.

Additional file 5:

Forest plots showing the results of subgroup analysis regarding the method (human/software) of PVA assessment (A) and sensitivity analysis for hospital mortality that was clearly defined at a time point (B) for ventilated patients with high patient–ventilator asynchrony (PVA) versus low PVA and clinical outcomes in Part A. A. 1, Duration of mechanical ventilation. A. 2, ICU mortality. A. 3, Hospital mortality. A. 4, Incidence of reintubation. A. 5, Incidence of tracheostomy. PVA, patient–ventilator asynchrony; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Additional file 6:

Risk of bias for each study by using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions in Part B.

Additional file 7:

Risk of bias for each study by using the Risk Of Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2). Additional considerations for cross-over trials in Part B.

Additional file 8:

Risk of bias for each study by using the Risk Of Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) in Part B.

Additional file 9:

Forest plots showing the effect of interventions for patient–ventilator asynchrony represented by the asynchrony index in Part B.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kyo, M., Shimatani, T., Hosokawa, K. et al. Patient–ventilator asynchrony, impact on clinical outcomes and effectiveness of interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. j intensive care 9, 50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-00565-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-00565-5