Abstract

Background

Cow milk is considered as one of the responsible food sources contaminated with heavy metals. The objectives of the study were to assess the content of selected metals in cow milk and its associated human health risks in the food chain of Bangladesh. A total of 90 cow milk samples of Branded, Dairy and Domestically produced milk were collected randomly from different sources of Savar Upazila in Dhaka area. Cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu) and iron (Fe) contents in collected milk samples were determined using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS). To ensure quality control, one of the best quality control parameters i.e. recovery test; from eight various sample digestion methods were used. The Hazard Quotient (HQ) and Carcinogenic Risk (CR) values were also calculated.

Results

From the results, it was found that, the orders of heavy metal content in brand, dairy and domestic cow milk were Cr > Fe > Cu > Mn > Cd > Pb, Cr > Fe > Mn > Cu > Cd > Pb and Fe > Cr > Mn > Cu > Cd > Pb, respectively. Among the six metals, only Cr showed to exceed the highest Estimated Daily Intake (EDI) rate (for brand cow milk: 0.413 mg/day, dairy farm cow milk: 0.243 mg/day, domestic cow milk: 0.352 mg/day),and the comparison percentages of calculated values per permeable values were as follows; 206.5 % for brand cow milk,121.5 % for dairy farm cow milk and 176.0 % for domestic cow milk. Hazard Quotients (HQ) values and Carcinogenic Risk (CR) values were found within the acceptable level.

Conclusion

Although, the metal content in sampled cow milks were within the safe limit, the potential human health risks cannot be neglected for the regular/long time consumption of heavy metal contained cow milk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Milk has a positive influence on human health. It is considered as nearly complete food since they are good source of proteins, fats, vitamin supplements and major minerals (Enb et al. 2009; Qin et al. 2009; Yuzbas et al. 2009; Salah and Ahmed 2012; Seyed and Ebrahim 2012). There are about 38 micro and trace elements reported to be found in raw milk from different regions around the world (Dobrzañski et al. 2005; Nwankwoala et al. 2002). These minerals content in raw cow milk may vary depending on several factors i.e. lactation period of cows, health conditions, seasonal variations, climatic conditions, annual feed composition and environmental contamination (Licata et al. 2004; Yahaya et al. 2010). The milk processing conditions may also have effective influence on the contents and retains of minerals in total composition of milk (Lante et al. 2006; Salah et al. 2013). All of these minerals including the trace elements in cow milk occurred as inorganic ions and remain with proteins, peptides, carbohydrates and other molecules (Vegarud et al. 2000). Most of these trace elements have beneficial health importance. For example they act like enzymatic co-factors that can play vital roles in different physiological functions of human body and lack of these minerals may cause distribution and pathological problems mainly in vulnerable age (Enb et al. 2009). The essential elements become toxic when the concentration level exceeds 40 to 200 fold from their respective recommended threshold value (Rao 2005). Malhatet et al. (2012) found that the contamination in milk is considered as one of the main dangerous aspects within the last few years.

Increased environmental pollution has accelerated the problems of milk contamination and uncertainties about milk qualities (Farid and Baloch 2012). The worldwide milk contamination via environmental pollutants and xenobiotic compounds through cattle feeds like toxic metals, mycotoxin, dioxin and other pollutants are considered to have greater influence on public health (Seyed and Ebrahim 2012). Uptake of these contaminated milk acts like an additional source of heavy metal exposure (Ruqia et al. 2015). The main sources of metal contamination to humans are industrial or domestic effluents, combustion, bushfires, decomposition of chemical fertilizers, pesticides etc. (Degnon et al. 2012). Abdominal pain, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, vomiting (Hussain et al. 2010), decreasing of intelligence quotient (IQ) level, Alzheimer’s disease, behavioral disorders (Ahmad et al. 2011), tissue injury, irritation of lungs, cancer (Bushra et al. 2014) etc. could be generated due to over exposure of heavy metals. Besides heavy metals are non-biodegradable in nature and become accumulated in the food chains via bio-transformation, bio-accumulation and biomagnifications (Aslam et al. 2011). Complete elimination or prevention of chemical contaminants cannot be achieved from milk because the lipophilic contaminants will find its way into the persistent fat compounds from where heavy metals cannot be removed readily (Girma et al. 2014). Schematic diagram of heavy metals entering into food chain is given in the Fig. 1.

Possible food chain pathways through which humans may be exposed to trace metals (Modified after Islam et al. 2015)

The heavy metal contamination of milk is less explored in less developed countries like Bangladesh (Islam et al. 2015; Shahriar et al. 2014). Islam et al. (2015) found that food chain around the nearby areas of Dhaka city in Bangladesh was contaminated by elements namely Cr, Ni, Cu, As, Cd and Pb through milk consumption in the study period of 2012–13. Besides the milk consumption rate in Bangladesh is very low (39.2 ml/day) while the recommended allowance is 250 ml/ day (Islam et al. 2015). According to previous survey, the annual milk production was 1.74 million tons during the year of 2001 and 2.28 million ton in 2007 (HIES 2011; BER 2007). Jamal and Fuad (2013),calculated that the milk production would be increased up to 4.55 million ton during the year of 2015–16. Moreover, with this increasing scenario in milk production, it is assumed that the consumer population of the country would face significant health threat in the long run from consuming contaminated milk and milk products. Thus the daily intake rate of heavy metal hazard quotients (HQ) and carcinogenic risk (CR) might be considered as exponentially increasing trend with the increasing rate of milk production.

The contamination of food stuffs due to metals and other toxins is one of the most important issues in developing countries. There are a lot of studies which have been conducted around the world associated with health risks for example; arsenic in cultivated rice in Srilanka (Channa et al. 2015), trace metal and alfatoxin in cassava flour in west Africa (Hayford et al. 2016),metals contaminated mushroom in Ethiopia (Medhanye et al. 2016), also health risk for contamination of foods and soils in China (Khan et al. 2008) and India (Sridhara Chary et al. 2008). However, it is observed that continuous long term exposures of consumers to heavy metal by consumption of cow milks get less emphasis in developing countries particularly in Bangladesh. Considering the aforementioned issues the study provides a significant importance in terms of public health hazard of Bangladesh. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate concentration of selected heavy metals contaminating cow milks in Bangladesh particularly in city areas.

Methods

Study area and sample collection

The study was conducted in the period from December 2014 to October 2015. A total of 90 cow milk samples were collected from different areas of SavarUpazila, Dhaka, Bangladesh (Fig. 2). The milk samples were classified according to their collection sources as (i) the popular packaged cow milk was considered as Brand milk (33 samples), (ii) the dairy farm milk (30 samples) collected from the available dairy farms and (iii) the milk samples collected from the small household farmers as domestic cow milk (27 samples). All the samples were collected in a sterile glass bottle following standard methods and stored at 4 °C until analysis.

Instrumental analysis

Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (FAAS) (Model: AA-6300, Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer, SHIMADZU, Japan) was used for heavy metal analysisforcadmium(Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), lead (Pb), and iron (Fe). Standard solution of each metal wasprepared at four different concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 5.0 ppm from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Spectral lines were set to 228.67, 357.65, 324.57, 279.43, 217.35 and 248.30 nm for Cd, Cr, Cu, Mn, Pb and Fe, respectively. The minimum detection limit (MDL) for Cd, Fe and Cu was 0.001 mg/kg; MDL for Mn and Pb was 0.002 mg/kg and for Cr MDL was 0.005 mg/kg. For ensuring the quality control we used the certified reference materials (CRM) for metal analysis and also performed the recovery test with the best digestion method for each metals (Table 2). The CRM for metal was purchased; Cd, Cr, Pb and Fe from Fluka, Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, USA) and Mn and Cu from Kanto chemicals co. Inc. (Tokyo, Japan).

Data calculation

Recovery test

Eight various methods for milk samples digestion were selected from previous related works to perform recovery test. Acid mixing ratiosHNO3 + HCLO4 (10 ml + 5 ml) were considered as M-1, HNO3 + H2O2 (10 ml + 3 ml) as M-2, Sample + HNO3 (1 gm + 5 ml) as M-3, HNO3 + HCLO4 (7 ml + 4 ml) as M-4, Supernatant Sample + HNO3 (15 ml + 5 ml) as M-5, HNO3+ HNO3 +HCLO4 + H2O2 (15 ml + 5 ml + 5 ml + drop wise) as M-6, HNO3+ H2O2 (6 ml + 1 ml) as M-7 and HNO3 + HCl + HF (2 ml + 6 ml + 2 ml) were set as M-8 for digestion of selected cow milk (Seyed and Ebrahim 2012; Nnadozie et al. 2014; Elatrash and Atoweir 2014; Rubina et al. 2013; Dawd et al. 2012; Jolanta et al. 1996; Tassew et al. 2014; European Committee for Standardization 2002). All of the reagents were from Merck (Darmstadt,Germany). The recovery percentages were calculated by the following equation:

Where, CE = Experimental concentration (ppm) and CM = Spiked Concentration (ppm)

Estimated daily intake (EDI) of metals due to milk consumption

The estimated daily intake (EDI) of trace metals inmilk depends on metal concentrations (for dry weight basis), and daily milk consumption rate as well as the average body weight.

Here, 39.2 mg/day = Daily milk consumption rate for Bangladesh (HIES 2011) and 60 kg = average body weight of an adult resident.

Ci = metal concentrations in milk (mg/l) (Islam et al. 2014).

Hazard quotients (HQs)

In the present study, the human health risks associated with the consumption of cow milk by the local community inhabitants were evaluated based on the hazard quotients (HQs). The method of estimating health risk using HQs was described in the USEPA Region III risk-based concentration table (USEPA 2000). The equation for HQ:

Here, EDI = estimated daily intake of metal (mg/day),

RfD = Oral Reference Dose (mg/kg/day). For Cr, Cd, Cu and Pb it is0.003, 0.001, 0.04 and 0.004, respectively (Islam et al. 2014; USEPA 2010). HQs indicate potential health risk when it is equal or higher than 1 (Islam et al. 2014).

Carcinogenic risk (CR)

The target carcinogenic risks (CR) were also calculated by using the equation provided in USEPA Region III Risk-Based Concentration Table (USEPA 2006):

Here, EFr = exposure frequency (350 days/year), ED = exposure duration (30 years) (USEPA 2006). AT = averaging time for carcinogens (365 days/year \( \times \) 70 years). CSFo stands for oral carcinogenic slope factor (USEPA 2010).

Results and discussion

Method validation and quality control

To determine recovery as one of the most important method validation parameters, eight various milk sample digestion methods (M-1 to M-8) were performed and results presented in Table 1. It is obvious that the highest recovery value was obtained for M-7 digestion method where HNO3 and H2O2 acids used were in the 6:1 ratio.(Tassew et al. 2014).

To ensure the quality control, the certified reference material (CRM) valuefor metal analysis with percentage of recovery for respective metalsarelisted in Table 2.

Heavy metal concentration incow milk

Concentrations of Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr), Lead (Pb), Manganese (Mn), Copper (Cu) and Iron (Fe) were determined in 90 cow milk samples (brand, dairy farm and domestic) using the most efficient digestion method (M-7) and results are summarized in Table 3

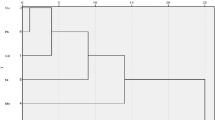

Average concentrations of trace metals among the branded cow milk samples had shown a descending order of Cr>Fe>Cu>Mn>Cd>Pb (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the dairy farm cow milk samples had shown the descending order of Cr>Fe>Mn>Cu>Cd>Pb while the average concentrations of trace metals among the domestic cow milk samples had shown the descending order of Fe>Cr>Mn>Cu>Cd>Pb (Fig. 3). It is clear from the figure that chromium possessed the highest concentration of metal content for both branded milk (0.672±0.010) and dairy cow milk (0.373±.008), while iron had shown the highest concentration (0.631±0.101) for the domestic cow milk. Lead had shown the least concentration for all types of sampled milk including 0.033±0.006 ppm for branded cow milk, 0.015±0.002 ppm for dairy farm cow milk and 0.012±0.001 ppm for domestic cow milk, respectively. Heavy metal contaminations in milk samples are found different countries all over the world in both brand milk and non-brand milk. A comparative scenario among previous studies around the world is illustrated in Table 4

Concentration of Cd was found extremely higher in one report from Pakistan (Mohammed et al. 2013) for both branded and non-brand milk samples (USEPA 2010) compared to the present study. In case of chromium both previous study from Bangladesh (Islam et al. 2015) and the present study had shown higher concentration compared to the other countries (USEPA 2006; Zodape et al. 2012). Similar results of higher concentration were also reported from branded milk of Indian study (Islam et al. 2014). Concentration of manganese was not reported previously from any type of cow milk. Lead samples had been reported higher in India (Islam et al. 2014) and Egypt (USEPA 2010) followed by Pakistan (Mohammed et al. 2013), Palestine (Abdul et al. 2012) and Nigeria (Ali et al. 2011) compared to the other reported countries (Seyed and Ebrahim 2012; Elatrash and Atoweir 2014; Khalil and Seliem 2013) including present study and previous study from Bangladesh (Islam et al. 2015). Concentration of cupper and iron had been found lower compared to the previous reports (Table 4).

Health risk assessment

The estimated daily intake (EDI) of metals from cow milk consumption had been investigated for selected metals. EDI and Permissible Values (PV) for metals studied, together with the contribution of EDI to PV (%), for adult consumers of cow milk (brand, dairy farm and domestic) are listed in Table 5.

To evaluate the daily intake, mean concentrations of metals in each cow milk category were multiplied by the milk consumption rate and divided by the body weight of the adult resident consumer. Metal specific EDIs revealed that EDI of Cr (for brand cow milk: 0.413 mg/day, for dairy farm cow milk: 0.243 mg/day and for domestic cow milk 0.352 mg/day) exceeded the permissible value (0.2 mg/day) and possess the highest concentration percentages to permissible value. EDIs of Cd, Pb, Mn, Cu and Fe were found below the permissible limits and also agreed with previous reports (Islam et al. 2015; Ademola 2014; Salah et al. 2012; Anita et al. 2010). Based on these data, this can be concluded that Cr was the major components contributing to the potential health risk via the consumption of all milk samples collected from Savar Upazila.

Hazard quotients (HQ) and carcinogenic risk (CR)

By definition, risk assessment is the evaluation process of the potential health effects from doses to human of one contaminant received through one or more exposure pathways. So, the potential health effects from doses to humans can be evaluated from risk assessment. By evaluating the hazard quotients (HQ), non-carcinogenic risks from consumption of foodstuffs by the adult inhabitants can be assessed. Based on the HQ we evaluated the non-carcinogenic risks due to consumption of cow milk for the adult resident and the estimated HQ values of metals are given in Table 6. From the results (Table 6) all the metals showed the HQ value below the threshold value of 1 suggested that there are no obvious health risks related to these metals associated with the consumption of cow milk in the study area. This finding agrees with Anita et al. 2010 and Islam et al. 2015. However the HQ value for each metal due to consumption of cow milk in the study area decreased in the order of: for brand milk; Cr>Cd>Pb>Mn>Cu>Fe, for dairy milk; Cr>Pb>Cd>Mn>Cu>Fe and for domestic cow milk; Cr>Cd>Mn>Cu>Fe>Pb. The data in the Table 6 also show the cumulative HQ (ƩHQs) did not exceed the suggested threshold valueof 1 but the ƩHQs value had decreased in the order of brand milk>domestic milk>dairy milk. This had revealedthat the brand milk hadhigher vulnerability to reach at the threshold for human health risks than the domestic and dairy cow milk. The carcinogenic risk (CR) of Pb due to consumption of cow milk by adult inhabitants in the study area was assessed using the target carcinogenic risk (CR). The result from the Table 6 showed the CR of Pb (Brand; 7.33×10−7, Dairy; 3.5×10−7 and Domestic; 1.0×10−7) due to consumption of cow milk was below 10−6 and considered as negligible. Due to the unavailability of carcinogenic slope factor values in USEPA 2010, most of the studied metals were not considered for direct CR assessment except for Pb. Therefore, the potential of CR for the inhabitants of the study area is within the safe limit, but the cumulative hazard quotients are nearing the threshold. Therefore, the non-carcinogenic health risk of the inhabitants due to consumption of cow milk should not be neglected.

Conclusion

To evaluate the safety of cow milk samples from Dhaka city area, selected heavy metal contents were analyzed by the most validated methods. Among the metals analyzed, Cr concentration along with their daily intake rate was found to be dominant percentages for both branded and non-branded cow milk samples. The current cumulative risks of studied metals due to consumption of cow milk remained below unity (HQ<1), indicating that people would not experience significant risk due to cow milk consumption. The studied direct carcinogenic risk of Pb is also below the recommended level (CR<10−6). But the cumulative HQs value is nearing the to the threshold, meaning due to regular consumption of cow milk along with its potential risk of contamination could lead to human health risks in the near future. It can be recommended that proper monitoring of cattle feed quality as well as the techniques of milk processing should be carefully considered for the public health safety in Bangladesh.

Abbreviations

- AT:

-

Averaging time for carcinogens

- BDL:

-

Below detection limit

- CR:

-

Carcinogenic risk

- CRM:

-

Certified reference materials

- CSFo:

-

stands for oral carcinogenic slope factor

- ED:

-

Exposure duration

- EDI:

-

Estimated daily intake

- EFr:

-

Exposure frequency

- FAAS:

-

Flame atomic absorption spectrometry

- HQ:

-

Hazard quotient

- MDL:

-

Minimum detection limit

- PV:

-

Permissible value

- RfD:

-

Oral reference dose

References

Abdul KA, Swaileh KM, Hussein RM, Matani M. Levels of metals (Cd, Pb, Cu and Fe) in cow’s milk, dairy products and hen’s eggs from the West Bank, Palestine. Int Food Res J. 2012;19(3):1089–94.

Ademola AK. Assessments of Natural Radioactivity and Heavy Metals in Commonly Consumed Milk in Oke-Ogun Area, Nigeria and Estimation of Health Risk Hazard to the Population. J Environ Anal Toxicol. 2014;4:253.

Ahmad N, Rahimb M, Mas H. Toxocological Impact Assessement of heavy metals in human blood and milk samples collected in district Shangla. Pakistan: SciInt (Lahore); 2011.

Alem G, Tesfahun K, Kassa B. Quantitative Determination of the Level of Selected Heavy Metals in the Cows’ Milk from the Dairy Farm of the Haramaya University, Eastern Ethiopia. Int J Chem Nat Sci. 2015;3(1):240–8.

Ali JA, Bukar DE, Jimoh N, Hauwa NT, Yusuf N, Umar ZT. Determination of copper, zinc, lead and some biochemical parameters in fresh cow milk from different locations in Niger State, Nigeria. Afr J Food Sci. 2011;5(3):156–60.

Anita S, Rajesh KS, Madhoolika A, Fiona MM. Health risk assessment of heavy metals via dietary intake of foodstuffs from the wastewater irrigated site of a dry tropical area of India. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:611–9.

Aslam B, Javed I, Hussain KF, Ur-Rahman Z. Uptake of Heavy Metal Residues from Sewerage Sludge in the Milk of Goat and Cattle during Summer Season. Pak Vet J. 2011;31(1):75–7.

BER. Bangladesh Economic Review, Ministry Of Finance. Dhaka: The Government of Bangladesh; 2007.

Bushra I, Saatea A, Samina S, Riaz K. Assessment of Toxic Metals in Dairy Milk and Animal Feed in Peshawar, Pakistan. British BiotechnolJ. 2014;4(8):883–93.

Channa J, Priyani P, Saranga F, Mala A, Sarath G, Sisira S. Presence of arsenic in Sri Lankan rice. Int J Food Contaminat. 2015;2:1.

Dawd AG, Gezmu TB, Haki GD. Essential and toxic metals in cow’s whole milk from selected sub-cities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Online Int J Food Sci. 2012;1(1):12–9.

Degnon RG, Dahouenon-Ahoussi E, Adjou ES, Soumanou MM, Dolganova NV, Sohounhloue DCK. Heavy metal contamination of the Nokoué Lake (southern Benin) and the dynamic of their distribution in organs of some fish’s species (Mugilcephalus L. and Tilapia guineensis). J Anim Sci Adv. 2012;2(7):589–95.

Dobrzañski Z, Kolacz R, Górecka H, Chojnacka K, Bartkowiak A. The content of microelements and trace elements in raw milk from cows in the Silesian region. Polish J Environ Stud. 2005;14(5):685–9.

Elatrash S, Atoweir N. Determination of lead and cadmium in raw cow’s milk by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy. Int J Chem Sci. 2014;12(1):92–100.

Enb A, AbouDonia MA, Abd-Rabou NS, Abou-Arab AAK, El-Senaity MH. Chemical Composition of Raw Milk and Heavy Metals Behavior During Processing of Milk Products. Global Veterinaria. 2009;3(3):268–75.

European Committee for Standardization. Characterization of waste- Microwave assisted digestion wihhydrofluoric (HF), nitric (HNO3) andhydrochloric (HCl) acid mixture for subsequent determination of elements. 2002. EN 13656.

FAO/WHO. Codex Alimentarius-general standards for contaminants and toxins in food. Schedule 1 Maximum and guideline levels for contaminants and toxins in food, Joint FAO/WHO food standards programme. Rotterdam: Codex committee; 2002. Reference CX/FAC 02/16.

Farag M, Mohammed H, Ayman S, Abd EF. Contamination of Cows Milk by Heavy Metal in Egypt. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2012;88:611–3.

Farid S, Baloch MK. Heavy metal ions in milk samples collected from animals feed with city effluent irrigated fodder. Greener J Physical Sciences. 2012;2(2):36–43.

Girma K, Tilahun Z, Haimanot D. Review on Milk Safety with Emphasis on Its Public Health. World J Dairy Food Sci. 2014;9(2):166–83.

Hayford O, Paa TA, Nanam TD. Variations in trace metal and aflatoxin content during processing of High Quality Cassava Flour (HQCF). Int J Food Contaminat. 2016;3:1.

HIES (Household Income and Expenditure Survey). Preliminary report on household income and expenditure survey-2010. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Division, Ministry of Planning; 2011.

Hussain Z, Nazir A, Shafique U, Salman M. Comparative study for the determination ofmetals in milk samples using Flame- AAS and EDTA complexometric titration. J Sci Res. 2010;1:55–76.

Islam MS, Ahmed MK, Al-mamun MH, Masunaga S. Trace metals in soil and vegetables and associated health risk assessment. Environ Monit Assess. 2014;186:8727–39.

Islam MS, Kawser MA, Habibullah MAM, Shigeki M. Assessment of trace metals in foodstuffs grown around the vicinity of industries in Bangladesh. J Food Compos Anal. 2015;42:8–15.

Jamal HM, Fuad HM. Forecasting of Milk, Meat and Egg Production in Bangladesh. Res J Animal, Vet Fishery Sci. 2013;1(9):7–13.

JECFA. Summary and conclusions of the 61st meeting of the joint FAO/WHO Expert committee on food additives (JECFA). Rome, Italy: JECFA/61/SC; 2003.

Jolanta BB, Ewa S, Wiestaw Z. Determination of Major and Trace Elements in Powdered Milk by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry. J Chem Anal. 1996;41:625.

Khalil HM, Seliem AF. Determination of Heavy Metals (Pb, Cd) and some Trace Elements in Milk and Milk Products Collected from Najran Region in K.S.A. Life Sci J. 2013;10(2):648–52.

Khan S, Cao Q, Zheng YM, Huang YZ, Zhu YG. Health risks of heavy metals in contaminated soils and food crops irrigated with wastewater in Beijing, China. Environ Pollut. 2008;152:686–92.

Lante A, Lomolino G, Cagnin M, Spettoli P. Content and characterization of minerals in milk in crescenza and squaquerone Italian fresh cheeses by ICP-OES. Food Control. 2006;17:229–33.

Licata P, Trombetta D, Cristani M, GiofreF MD, Calo M, Naccari F. Levels of “toxic” and “essential” metals in samples of bovine milk from various dairy farms in Calabria, Italy. Environ Int. 2004;30:1–6.

Malhat F, Hagag M, Saber A, Fayz AE. Contamination of cow’s milk by heavy metal in Egypt. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2012;88(4):611–3.

Medhanye G, Negussie M, Abi MT. Levels of essential and non-essential metals in edible mushrooms cultivated in Haramaya, Ethiopia. Int J Food Contaminat. 2016;3:2.

Mohammed AGA, Abubakar Musa KE, WaleedAboshora WZ. Evaluation of some physicochemical parameters of three commercial milk products. Pak J Food Sci. 2013;23(2):62–5.

Nnadozie CU, Birnin-Yauri UA, Muhammad C. Assessment of Some Diary Products Sold in Sokoto Metropolis, Nigeria. Int J Adv Res Chem Sci. 2014;1(10):31–7.

Nwankwoala A, Odueyungbo S, Nyavor K, Egiebor N. Levels of 26 elements in infant formula from USA, UK and Nigeria by microwave digestion and ICP-OES. Food Chem. 2002;77(4):439–47.

Ogabiela EE, Udiba UU, Adesina OB, Hammuel C, Ade-Ajayi FA, Yebpella GG, Mmereole UJ, Abdullahi M. Assessment of metal levels in fresh milk from cows grazed around Challawa Industrial Estate of Kano, Nigeria. J Basic Appl Sci Res. 2011;1(7):533–8.

Oliver MA. Soil and human health: A Review. Eur J Soil Sci. 1997;48:573–92.

Qin LQ, Wang XP, Li W, Tong WJ TX. The minerals and heavy metals in cow’s milk from China and Japan. J Health Sci. 2009;55(2):300–5.

Rao AN. Trace element estimation: methods and clinical context.Online. J Health Allied Sci. 2005;4(1):1–9.

Rubina P, Abbas B, Darakhshan A, Shahid SS, Qamar-ul H. Elucidation of physico-chemical characteristics and mycoflora of bovine milk available in selected area of Karachi, Pakistan. J Appl Sci Environ Manag. 2013;17(2):259–65.

Ruqia N, Muslim K, Hameed UR, Zubia M, Muhammad M, Rumana S, Naila G, Faryal S, Irum P, Fathma S, Muhammad Z, Noor UA, Nelofer J. Elemental Assessment of Various Milk Packs Collected From KPK, Pakistan. Am-Eurasian J Toxicol Sci. 2015;7(3):157–61.

Salah F, Ahmed AEA. Assessment of Toxic Heavy Metals in Some Dairy Products and the Effect of Storage on its Distribution. J Ameri Sci. 2012;8(8):665–70.

Salah AEA, Esmat AI, Rania MKM. Prevalence of Some Trace and Toxic Elements in Raw and Sterilized Cow’s Milk. J Am Sci. 2012;8(9):753–61.

Salah FA, Esmat IA, Mohamed AB. Heavy metals residues and trace elements in milk powder marketed in DakahliaGovernorate. Int Food ResJ. 2013;20(4):1807–12.

Seyed MD, Ebrahim R. Determination of Lead Residue in Raw Cow Milk from Different Regions of Iran by Flameless Atomic Absorption Spectrometry. Am-Eurasian J Toxicol Sci. 2012;4(1):16–9.

Shahriar SMS, Akther S, Akter F, Morshed S, AlamMK SI, Halim MA, Hassan MM. Concentration of Copper and Lead in Market Milk Concentration of Copper and Lead in Market Milk. Int Letters Chem, Phys Astro. 2014;27:56–63.

Solidum JN, Burgos SG, dela Cruz KM, Padilla R. A Quantitative Analysis on Cadmium and Chromium Contamination in Powdered Children’s Milk. Metro Manila, Philippines: International Conference on Environment and Bioscience; 2012.

Sridhara Chary N, Kamala CT, Samuel Suman Raj D. Assessing risk of heavy metals from consuming food grown on sewage irrigated soils and food chain transfer. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2008;69:513–24.

Tassew B, Ahmed H, Vegi MR. Determination of Concentrations of Selected Heavy Metals in Cow’s Milk. J Health Sci. 2014;4(5):105–12.

USEPA. Risk-based Concentration Table US Environmental Protection Agency Washington. DC/Philadelphia: PA; 2000.

USEPA. USEPA Region III Risk-Based Concentration Table: Technical Back-ground Information. Washington: Unites States Environmental Protection Agency; 2006.

USEPA (2010) Risk Based Concentration Table. Available from: http://www.epa.gov/reg3hwmd/risk/human/index.htm.

Vegarud GE, Landsrud T, Svaning C. Mineral-binding milk proteins and peptides; occurrence, biochemical and technological characteristics. Br J Nutr. 2000;84:91–8.

Yahaya MI, Ezo GC, Musa YF, Muhamad SY. Analysis of heavy metals concentration in roadside soils in Yauri, Nigeria. Afr J Pure Appl Chem. 2010;4(3):022–30.

Yuzbas I, Sezgin NE, Yldrm Z, Yldrm M. Changes In Pb, Cd, Fe, Cu and Zn Levels during the Production of Kasar Cheese. J Food Qual. 2009;32:73–83.

Zodape GV, Dhawan VL, Wagh RR. Determination of Metals in Cow Milk Collected From Mumbai City, India. Srilanka: Eco Revolution Colombo; 2012. p. 270–4.

Author’s contribution

MIM contributed to study design, sampling, instrumental analysis and writing; MAZC, NJE, ZF, MLB and MKA contributed to carry out instrumental analysis and sampling; MMR, MS, MKU, MK contributed to study design, manuscript preparing, data analysis, paper review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

This is an original manuscript that has not been submitted elsewhere for publication. All authors have read the manuscript and agreed that the work is ready for submission to the journal with no conflict of interests. The author Md. Mostafizur Rahman will represent for all correspondence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhib, M.I., Chowdhury, M.A.Z., Easha, N.J. et al. Investigation of heavy metal contents in Cow milk samples from area of Dhaka, Bangladesh. FoodContamination 3, 16 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40550-016-0039-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40550-016-0039-1