Abstract

We report the electronic absorption spectroscopy of 7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) and its fluorinated derivatives (F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ), well-known electron-accepting molecules in common organic solvents (toluene, chlorobenzene, acetonitrile, and ethanol) under controlled exposure to air (O2) and UV light. All compounds (FxTCNQ (x = 0, 2, 4)) were stable in a neutral state (FxTCNQ0) in toluene and chlorobenzene, even under both O2 and UV light. On the other hand, in EtOH, the formation of FxTCNQ·− was monitored upon controlled exposure to O2 or UV light. Especially in air-equilibrated ethanol upon the UV-illumination, efficient α,α-dicyano-p-toluoylcyanide anion (DCTC−) and its fluorinated derivatives were generated evinced by the absorption peak near 480 nm, whereas the reaction was shut off by removing O2 or blocking UV light, thereby keeping FxTCNQ·− stable. However, even in deaerated ethanol, upon the UV-illumination, the anion formation of TCNQ and its fluorinated derivatives (FxTCNQ·−, x = 0, 2, 4) was inevitable, showing the stability of FxTCNQ0 depends on the choice of solvent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic semiconducting molecules have received attention for their applications in biosensors, nonlinear optics, transistors, optoelectronics due to their nontoxicity, bandgap tunability, facile fabrication, and flexibility (Kim et al. 2022; Cha et al. 2020; Bronstein et al. 2020; Yuan et al. 2019; Sun et al. 2019; Oh et al. 2019; Hiramoto et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Nayak et al. 2016; Feier et al. 2016; Mishra and Bäuerle 2012; Hains et al. 2010; Coropceanu et al. 2007; Suchanski and Duyne 1976; Yanti et al. 2021). Despite an intrinsically large exciton binding energy (EB > ~ 100 meV–1 eV) in organic semiconductors, organic charge transfer (CT) complexes have shown strikingly high conductivity (σ > 102 S cm–1), comparable to metals (Saito and Yoshida 2007). These molecular electronics have motivated the synthesis of new functional molecules, and their optical/electrical/photophysical properties have been examined.

7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) in Fig. 1 is a well-known electron-acceptor molecule and has been utilized in various molecular electronics with its LUMO energy level at − 4.23 eV (Kanai et al. 2009) that matches well with diverse electron donor molecules to produce functional CT complexes (Zhang et al. 2018). TCNQ undergoes one or two electron reduction reactions to form stable anion by-products, TCNQ·− and TCNQ2− (Vishwanath et al. 2019). Previously, the spontaneous formation of α,α-dicyano-p-toluoylcyanide anion (DCTC−) has been observed in TCNQ solution. Several potential mechanisms have been proposed (Ning et al. 2019; Hertler et al. 1962; Mizoguchi et al. 1978; Kryszewski et al. 1981; Grossel et al. 2000; Le et al. 2011), one of which includes the reaction of reduced TCNQ2− with dissolved O2(g) to produce DCTC− in ambient solution (Ning et al. 2019). On the other hand, several conflicting mechanisms of the formation of DCTC−, involving neutral TCNQ or TCNQ·− also have been reported as well (Hertler et al. 1962; Mizoguchi et al. 1978; Kryszewski et al. 1981; Grossel et al. 2000).

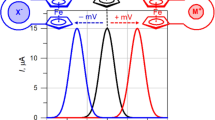

For further energy level engineering, several fluorinated derivatives, tetrafluorinated/difluorinated TCNQ (F4TCNQ and F2TCNQ), were developed and successfully have shown the tunability of the first reduction potential with respect to TCNQ: E1/2(TCNQ·−/TCNQ) = − 54 mV; E1/2(F2TCNQ·−/F2TCNQ) = + 165 mV; E1/2(F4TCNQ·−/F4TCNQ) = + 365 mV versus Ag/Ag+ in CH3CN (Le et al. 2011; Miyasaka et al. 2010). Furthermore, these fluorinated TCNQ derivatives have been shown to form radical anions and dianions in polar solvents such as acetonitrile and ethanol (Ma et al. 2014; Vo et al. 2018; Chae et al. 2014), while external conditions such as O2 or UV light for anion species formation have not been well characterized. Therefore, to utilize the electron-accepting property of TCNQ and its fluorinated derivatives in many devices, it is crucial to understand the conditions to keep TCNQ derivatives neutral (TCNQ0) and to prevent from producing by-products such as anions or DCTC−. In this regard, the role of O2 and UV light on the spectroscopic properties of TCNQ derivatives is worth investigating. Here, we report the electronic absorption spectroscopy of 7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) and its fluorinated derivatives (F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ) in various common organic solvents (toluene-Tol, chlorobenzene-CB, acetonitrile-ACN, and ethanol-EtOH) either as air-equilibrated or as N2-purged with controlled UV-illumination. TCNQ showed the production of DCTC− upon the reaction of TCNQ·− with O2 in EtOH under UV-illumination, whereas in N2-purged EtOH, no or minimal DCTC− was observed. On the other hand, stable neutral form TCNQ0 was confirmed in Tol, CB, or ACN. Similarly, F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ in air-equilibrated EtOH exhibited the effective production of fluorinated DCTC− derivatives with an absorption peak near 480 nm under UV, which was suppressed by removing O2 or blocking UV light.

Experimental section

Materials

7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ), 2,5-Difluoro-7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (F2TCNQ), and tetrafluorotetracyanoquinodimethane (F4TCNQ, purified from sublimation) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI) and used without further purification. Ethanol (HPLC/spectrophotometric grade, Sigma-Aldrich), acetonitrile (HPLC/spectrophotometric grade, J. T. Baker), toluene (HPLC grade, Wako Chemicals), and chlorobenzene (HPLC grade, Sigma-Aldrich) were used as received.

Instrumentation

Electronic absorption spectra were acquired using a Hitachi U-3900 UV/visible/NIR spectrophotometry system in a quartz optical cell. Baseline corrections for the transmittance of an optical cell with solvent were made prior to each measurement. In addition, the evolution of an absorption spectrum upon the UV-illumination (365 nm, 4 W, CW UV lamp) was monitored either with molecular oxygen in an air-equilibrated solution or without molecular oxygen in an N2 (99.999% purity)-purged solution to examine the absorption behavior of TCNQ derivatives, dependent on the presence of O2.

Results and discussion

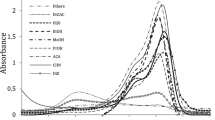

To fabricate OPV devices or to prepare solution samples for photocatalyst characterization, electrical or photophysical studies involving TCNQ, solution processes are commonly used. In this regard, electronic absorption spectra of TCNQ were explored in various common organic solvents: toluene (Tol), chlorobenzene (CB), acetonitrile (ACN), and ethanol (EtOH). Additional file 1: Figure S1 displays the electronic absorption spectra of TCNQ in air-equilibrated solvents, and the spectroscopic results are tabulated in Table 1. In all solvents, the absorption spectra of TCNQ revealed the characteristic S0 → S1 transition in the range of 394–403 nm, consistent with the previous literature results (Suchanski and Duyne 1976). However, in Additional file 1: Figure S1d (black line), TCNQ in EtOH displays additional dual peaks in 700–900 nm, which are typical peaks for TCNQ anion radical (TCNQ·−) (Melby et al. 1962).

The spectroscopic behavior of TCNQ was further tracked upon UV light illumination every 3-min to examine its photostability for a total of 15 min, as shown in Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Figures S1 and S3. The spectroscopic results of TCNQ, either in air-equilibrated Tol, CB, or ACN, showed a virtually consistent absorption spectrum. In contrast, TCNQ in air-equilibrated EtOH (EtOH-air) exhibited a substantial drop of the intensity for the absorption band at 396 nm even in 3 min in Fig. 2a. With the decrease of 396 nm band, multiple absorption bands at 421, 743, and 841 nm, corresponding to TCNQ·− increased, and a new band at 474 nm emerged. At 6 min (green in Fig. 2a), even the absorption bands of TCNQ·− at 421, 743, and 841 nm began to decrease, and the 474 nm band continuously gained its intensity up to 15 min (magenta line in Fig. 2a), when the original absorption peak at 396 nm was wholly disappeared. The spectral change for TCNQ in EtOH-air in Fig. 2a suggests that TCNQ reacted to generate TCNQ·−, in contrast to stable TCNQ0 in Tol, CB, or ACN. Furthermore, the spectral evolution upon the UV-illumination from 3 to 15 m, featuring the decrease of 743 and 841 nm band, implies that TCNQ·− was reacted to produce the species that shows an absorption peak at 474 nm. The new species that shows the absorption band at 474 nm has been ascribed to α,α-dicyano-p-toluoylcyanide anion (DCTC−, Additional file 1: Figure S2) previously (Suchanski and Duyne 1976; Hertler et al. 1962; Mizoguchi et al. 1978; Kryszewski et al. 1981; Grossel et al. 2000; Xiulan et al. 2012), and the details of DCTC− generation are discussed below. No sign of TCNQ2− with a peak at ~ 330 nm was observed during this spectroscopic evolution, contrasting to the previous studies in ACN (Suchanski and Duyne 1976; Chae et al. 2014).

Due to the potential role of molecular oxygen (O2) in air-equilibrated EtOH in DCTC− generation, the spectroscopic behavior of TCNQ was further examined in degassed EtOH (EtOH-N2) by pre-purging EtOH solvent and purging TCNQ solution in EtOH with high purity (99.999%) N2 gas. Figure 2b displays the spectral evolution upon the same UV-illumination. Like the absorption spectrum of TCNQ in EtOH-air at 0 m in Fig. 2a (black line), TCNQ in EtOH-N2 also exhibited the characteristic 396 nm band for TCNQ0 in addition to 743 and 841 nm bands corresponding to TCNQ·− in Fig. 2b (black line). At 3 m (red line), TCNQ·− peaks increased with the decrease of TCNQ peak, and the additional band at 421 nm is also the spectroscopic fingerprint of TCNQ·−, which was buried with TCNQ0 band at 0 m due to the spectral proximity. From 6 min (green line), the spectral change in EtOH-N2 contrasts with that in EtOH-air, lacking the growth of the DCTC− absorption band at 474 nm. Also, the absorption peak intensity of TCNQ·− peaks in EtOH-N2 was kept constant, suggesting stable TCNQ·− and no further reactions consuming TCNQ·− occurred. The formation of DCTC− in EtOH-N2 could be blocked because of the absence of TCNQ·− even without O2. Additional file 1: Figure S4 presents the absorption spectra of TCNQ as a function of time passed since blocking UV light in the middle of UV-illumination (exposed to UV light for 9 min), clearly showing the presence of TCNQ·−. Over the 10 min since blocking UV light, no DCTC− generation was noticed, highlighting the role of both O2 and TCNQ·−.

Since the initial report of TCNQ, several DCTC− generation mechanisms from TCNQ have been proposed, whether the reaction starts either from TCNQ0, TCNQ·−, or TCNQ2− (Hertler et al. 1962; Mizoguchi et al. 1978; Kryszewski et al. 1981; Grossel et al. 2000; Xiulan et al. 2012). To identify the origin of DCTC− formation, we plotted the absorbance (Abs474) of DCTC− product, monitored at 474 nm against the absorbance (Abs841) of TCNQ·− at 841 nm using the data in Fig. 2a. If DCTC− is produced from TCNQ·−, as the stoichiometry of TCNQ·− and DCTC− is 1:1 based upon the potential mechanism shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2, the concentration of the produced DCTC− ([DCTC−]p,t) at a given t should be equivalent to that of the consumed TCNQ·− ([TCNQ·−]c,t) at the same t.

From the Beer’s law:

where εx(A) is the molar absorption coefficient at x nm for A species. Therefore, from the equivalence in Eq. (1) as well as Eqs. (2) and (3), the Abs474 should be linearly proportional to Abs841 as in Eq. (4), and the proportionality constant would be the ratio of ε474(DCTC−) to ε841(TCNQ·−):

Figure 3a displays the Abs474(DCTC−) against Abs841(TCNQ·−), and the linear fit determined the proportionality constant to be −0.814 (± 0.03). From the literature, ε474(DCTC−) and ε841(TCNQ·−) have been reported in various solvents. Using ε474(DCTC−) = 38,800 cm−1 M−1 and ε841(TCNQ·−) = 43,500 cm−1 M−1 in acetone (Hertler et al. 1962; Grossel et al. 2000; Melby et al. 1962), ε474(DCTC−)/ε841(TCNQ·−) can be calculated to be 0.892, which matches reasonably well despite the solvent difference. In addition, Abs841(TCNQ·−) is plotted against the UV-illumination time in Fig. 3b, showing the pseudo-first-order reaction for TCNQ·− behavior is observed, again supporting that the reaction of TCNQ·− is not mediated by the self-collisions, consistent with the proposed mechanism by Hipps et al. (Qi et al. 2012) and the resulting fit determined the rate constant to be 0.13 m−1.

Structurally related fluorinated TCNQ molecules (F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ: FxTCNQ, x = 2 and 4) have been widely utilized as comparative and tunable functional molecules to TCNQ, as their spectroscopic signatures are similar in spite of the modified reduction energy levels. The absorption spectra of FxTCNQ, either EtOH-air or EtOH-N2, in Fig. 4a, b, d, e showed substantial change over time, like TCNQ in EtOH. On the other hand, as presented in Additional file 1: Figure S5a, b, d, e, no appreciable spectral change was probed in Tol or CB even under UV-illumination, while in ACN, F4TCNQ showed a noticeable decrease in 387 nm band, contrasting to F2TCNQ that displayed no spectral change (Figure S5c, f). This is likely due to the higher electron affinity of F4TCNQ, resulting in the reduction of F4TCNQ. On the other hand, in EtOH-air, both F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ in Fig. 4a, b, d, e displayed a dramatic change as in TCNQ. As the formation of an oxidized product, DCTC− from TCNQ·− was evident from a new absorption band at ~ 480 nm in Fig. 2a, F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ in EtOH-air similarly show the rise of ~ 480 nm band under UV light. Congruent to TCNQ, in EtOH-N2, the effective growth of the 480 nm band was not observed, again suggesting that fluorinated DCTC− derivatives were not produced without O2. Additionally, even in EtOH-air, without UV light, FxTCNQ·− (x = 0, 2, 4) was not effectively generated in Fig. 4c, f, evincing the stable neutral TCNQ0 and F2TCNQ0, contrary to unstable F4TCNQ that underwent F4TCNQ2− formation (Melby et al. 1962).

Conclusions

In summary, the electronic absorption spectroscopy of FxTCNQ (x = 0, 2, 4) probed the stability of FxTCNQ (x = 0, 2, 4) in common organic solvents upon controlled exposure to O2 or UV light. In general, all FxTCNQ compounds were stable in Tol and CB even under both O2 and UV light, whereas in EtOH, the FxTCNQ·− formation was monitored. Furthermore, in air-equilibrated EtOH upon UV-illumination, efficient α,α-dicyano-p-toluoylcyanide anion (DCTC−) and its fluorinated derivatives were generated, whereas the reaction was shut off by removing O2 or blocking UV light. With the significance of TCNQ and its derivatives (F2TCNQ and F4TCNQ) not only in molecular electronics but also in electrochemistry, this work will provide an understanding of the impact of external stimuli such as O2 and UV light on TCNQ compounds.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Supplementary Information is available.

References

Bronstein H, Nielsen CB, Schroeder BC, McCulloch I. The role of chemical design in the performance of organic semiconductors. Nat Rev Chem. 2020;4(2):66–77.

Cha W-Y, Lee J-Y, Park J, Koo YH, Park J, Seki S, et al. Poly(3-hexylthiophene) crystalline cubes: a facile preparation of polymer particles featuring long-range ordering. Chem Lett. 2020;49(12):1494–6.

Chae IS, Kang SW, Kang YS. Olefin separation via charge transfer and dipole formation at the silver nanoparticle–tetracyanoquinoid interface. RSC Adv. 2014;4(57):30156–61.

Coropceanu V, Cornil J, da Silva Filho DA, Olivier Y, Silbey R, Brédas J-L. Charge transport in organic semiconductors. Chem Rev. 2007;107(4):926–52.

Feier HM, Reid OG, Pace NA, Park J, Bergkamp JJ, Sellinger A, et al. Local intermolecular order controls photoinduced charge separation at donor/acceptor interfaces in organic semiconductors. Adv Energy Mater. 2016;6(6):1502176.

Grossel MC, Duke AJ, Hibbert DB, Lewis IK, Seddon EA, Horton PN, et al. An investigation of the factors that influence the decomposition of 7, 7′, 8, 8′-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) and Its salts to, and structural characterization of, the α, α-dicyano-p-toluoylcyanide anion. Chem Mater. 2000;12(8):2319–23.

Hains AW, Liang Z, Woodhouse MA, Gregg BA. Molecular semiconductors in organic photovoltaic cells. Chem Rev. 2010;110(11):6689–735.

Hertler W, Hartzler H, Acker D, Benson R. Substituted quinodimethans. III. Displacement reactions of 7, 7, 8, 8-tetracyanoquinodimethan. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84(17):3387–93.

Hiramoto M, Kikuchi M, Izawa S. Parts-per-million-level doping effects in organic semiconductor films and organic single crystals. Adv Mater. 2019;31(1):1801236.

Kanai K, Akaike K, Koyasu K, Sakai K, Nishi T, Kamizuru Y, et al. Determination of electron affinity of electron accepting molecules. Appl Phys A. 2009;95(1):309–13.

Kim K, Yoo H, Lee EK. New opportunities for organic semiconducting polymers in biomedical applications. Polymers. 2022;14(14):2960.

Kryszewski M, Ciesielski W, Pȩlcherz J. Decomposition of complexes of TCNQ anion radical salts as a function of time. Acta Polym. 1981;32(9):524–31.

Le TH, Nafady A, Qu X, Martin LL, Bond AM. Detailed electrochemical analysis of the redox chemistry of tetrafluorotetracyanoquinodimethane TCNQF4, the radical anion [TCNQF4]·–, and the dianion [TCNQF4]2– in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid. Anal Chem. 2011;83(17):6731–7.

Ma L, Hu P, Kloc C, Sun H, Michel-Beyerle ME, Gurzadyan GG. Ultrafast spectroscopic characterization of 7, 7, 8, 8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) and its radical anion (TCNQ−). Chem Phys Lett. 2014;609:11–4.

Melby L, Harder R, Hertler W, Mahler W, Benson R, Mochel W. Substituted quinodimethans. II. Anion-radical derivatives and complexes of 7, 7, 8, 8-tetracyanoquinodimethan. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84(17):3374–87.

Mishra A, Bäuerle P. Small molecule organic semiconductors on the move: promises for future solar energy technology. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51(9):2020–67.

Miyasaka H, Motokawa N, Matsunaga S, Yamashita M, Sugimoto K, Mori T, et al. Control of charge transfer in a series of Ru2II, II/TCNQ two-dimensional networks by tuning the electron affinity of TCNQ units: a route to synergistic magnetic/conducting materials. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(5):1532–44.

Mizoguchi K, Tsuji S, Tsuchida E, Shinohara I. Chemical stability and electroconductivity of 7, 7, 8, 8-tetracyanoquinodimethane salts containing polycation polymers. J Polym Sci Part A: Polym Chem. 1978;16(12):3259–74.

Nayak A, Park J, De Mey K, Hu X, Duncan TV, Beratan DN, et al. Large hyperpolarizabilities at telecommunication-relevant wavelengths in donor–acceptor–donor nonlinear optical chromophores. ACS Cent Sci. 2016;2(12):954–66.

Ning X, Li Y, Ming J, Wang Q, Wang H, Cao Y, et al. Electronic synergism of pyridinic-and graphitic-nitrogen on N-doped carbons for the oxygen reduction reaction. Chem Sci. 2019;10(6):1589–96.

Oh S, Kim JH, Park SK, Ryoo CH, Park SY. Fabrication of pixelated organic light-emitting transistor (OLET) with a pure red-emitting organic semiconductor. Adv Opt Mater. 2019;7(23):1901274.

Qi Y, Mazur U, Hipps K. Charge transfer induced chemical reaction of tetracyano-p-quinodimethane adsorbed on graphene. RSC Adv. 2012;2(28):10579–84.

Saito G, Yoshida Y. Development of conductive organic molecular assemblies: organic metals, superconductors, and exotic functional materials. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2007;80(1):1–137.

Suchanski MR, Van Duyne RP. Resonance Raman spectroelectrochemistry. IV. The oxygen decay chemistry of the tetracyanoquinodimethane dianion. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98(1):250–2.

Sun L, Hua W, Liu Y, Tian G, Chen M, Chen M, et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence in an organic cocrystal: narrowing the singlet-triplet energy gap via charge transfer. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58(33):11311–6.

Vishwanath R, Nery EW, Jönsson-Niedziółka M. Electrochemical reduction of 7, 7, 8, 8-tetracyanoquinodimethane at the n-octyl pyrrolidone/water/electrode three-phase junction. J Electroanal Chem. 2019;854:113558.

Vo N, Haworth NL, Bond AM, Martin LL. Investigation of the redox and acid-base properties of TCNQF and TCNQF2: electrochemistry, vibrational spectroscopy, and substituent effects. ChemElectroChem. 2018;5(8):1173–85.

Wang C, Dong H, Jiang L, Hu W. Organic semiconductor crystals. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(2):422–500.

Xiulan J, Zuowei L, Chenglin S, Xueya Z. Study of electron transfer process of TCNQ under external electric field. Int J Phys Sci. 2012;7(6):901–5.

Yanti S, Wu Z-W, Agrawal DC, Chien W-J. Interaction between phloretin and insulin: a spectroscopic study. J Anal Sci Tech. 2021;12(1):1–16.

Yu J, Park J, Van Wyk A, Rumbles G, Deria P. Excited-state electronic properties in Zr-based metal-organic frameworks as a function of a topological network. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(33):10488–96.

Yuan J, Zhang Y, Zhou L, Zhang G, Yip H-L, Lau T-K, et al. Single-junction organic solar cell with over 15% efficiency using fused-ring acceptor with electron-deficient core. Joule. 2019;3(4):1140–51.

Zhang J, Jin J, Xu H, Zhang Q, Huang W. Recent progress on organic donor–acceptor complexes as active elements in organic field-effect transistors. J Mater Chem C. 2018;6(14):3485–98.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ewha Womans University Research Grant of 2021 and National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (NRF-2020R1F1A1073716).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB executed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. JP analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Figure S1: Electronic absorption spectra of TCNQ in a various solvent as a function of UV-illumination time in air-equilibrated condition: toluene (Tol), chlorobenzene (CB), acetonitrile (ACN), ethanol (EtOH). Figure S2: The formation of DCTC− from TCNQ radical anion upon the exposure to O2 and UV light. Figure S3: Normalized electronic absorption spectra of TCNQ in a various solvent as a function of UV-illumination time in air-equilibrated condition: toluene (Tol), chlorobenzene (CB), and acetonitrile (ACN). Figure S4: Electronic absorption spectra of TCNQ as a function of time passed since blocking UV light with the initial 9 mins of UV-illumination. Figure S5: Electronic absorption spectra of (a,b,c) F2TCNQ and (d,e,f) F4TCNQ in toluene (Tol; a,d), chlorobenzene (CB; b,e), and acetonitrile (ACN; c,f) as a function of UV-illumination time in air-equilibrated condition. Figure S6: (a-c) Electronic absorption spectra of (a) TCNQ, (b) F2TCNQ, and (c) F4TCNQ in deaerated EtOH as a function of time without UV-illumination.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bang, J., Park, J. The role of molecular oxygen (O2) and UV light in the anion radical formation and stability of TCNQ and its fluorinated derivatives. J Anal Sci Technol 14, 2 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-022-00364-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-022-00364-z