Abstract

Due to the widespread emergence of COVID-19, face masks have become a common tool for reducing transmission risk between people, increasing the need for sterilization methods against mask-contaminated microorganisms. In this study, we measured the efficacy of ultraviolet (UV) laser irradiation (266 nm) as a sterilization technique against Bacillus atrophaeus spores and Escherichia coli on three different types of face mask. The UV laser source demonstrated high penetration of inner mask layers, inactivating microorganisms in a short time while maintaining the particle filtration efficiency of the masks. This study demonstrates that UV laser irradiation is an efficient sterilization method for removing pathogens from face masks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Face masks are commonly used to prevent inhalation of environmental air pollutions such as yellow dust and fine particles. During the COVID-19 pandemic, face masks and facepiece respirators have been an important aspect of reducing the risk for human-to-human transmission of COVID-19 through bioaerosols and droplets. However, due to a shortage of personal protective equipment, the reuse of face masks is often required (Celina et al. 2020; Cramer et al. 2021), highlighting the importance of sterilization methods to reduce microorganisms on face masks prior to rewear. A proper sterilization method would also help to sterilize contaminated respirators before disposal, keeping them out of the environment (Hossain et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2021).

A growing number of sterilization methods have been introduced to eliminate microorganisms such as viruses, bacterial cells, and bacterial spores on face masks and respirators (Rodriguez-Martinez et al. 2020). Dry heat is effective for inactivating viruses and bacteria after 2 h exposure but causes a sharp reduction in particle filtration efficiency with temperatures higher than 100 °C (Oh et al. 2020; Pascoe et al. 2020). Chemical-based agents such as hypochlorite, hydrogen peroxide, ethanol, isopropanol, and detergents also decrease filtration efficiency, and lingering chemical residues can generate unpleasant odors and damage the skin (Derraik et al. 2020; Jung et al. 2020; McEvoy et al. 2019; Viscusi et al. 2009). While gamma irradiation is widely used to sterilize medical devices, it also reduces the filtration performance of respiratory devices (DeAngelis et al. 2021). Exposure to ultraviolet C (UV-C, 200–280 nm) light is one of the most commonly used sterilization methods (Jang et al. 2022) because it is effective against bacterial cells and spores with little to no effect on filtration efficiency in respiratory devices.(Lindsley et al. 2015; Nguyen et al. 2021; Paul et al. 2020). The most challenging aspect of the use of UV radiation is that microorganism sterilization can vary between non-porous and porous surfaces due to a shadowing effect (Banerjee et al. 2021; Kayani et al. 2021). There is concern that UV radiation will have reduced sterilization efficiency on inner layers of masks which are not directly exposed to the UV source.

Pathogens from both spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria pose potential threats to public health (Post 2019). Bacillus are spore-forming, Gram-positive species whose spores are metabolically dormant and greatly resistant to disinfectants. Bacillus strains are associated with food poisoning (Bacillus cereus) (Stenfors Arnesen et al. 2008), insect pathogens (Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus sphaericus) (Aronson et al. 1986), and bioterrorism agents (Bacillus anthracis) (Spotts Whitney et al. 2003). Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacterium commonly found in the intestines of people and other animals. E. coli O157:H7 leads to severe stomach cramps, bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and acute kidney failure (Armstrong et al. 1996; Doyle 1991). Multidrug-resistant strains of E. coli have also been reported to interfere with the treatment of bloodstream (Paramita et al. 2020) and urinary tract infections (Manges et al. 2001), and when a host is immunosuppressed or when gastrointestinal barriers are invaded, even non-pathogenic E. coli can cause infections (Kaper et al. 2004).

This study investigated the sterilization of Bacillus atrophaeus spores and E. coli on face masks using a neodymium-doped yttrium orthovanadate (Nd:YVO4) UV laser (266 nm, 1 W) with different numbers of scans. The impact of laser treatment was quantitatively examined according to the viability of microorganisms and the particle filtration efficiency of the masks.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

Bacillus atrophaeus spores (PTG706) and E. coli (PTG708) strains were purchased from Protigen (Protigen Corp., Jeonju, Jeollabuk-do, Korea). Both standard colony-forming units were ~ 108 CFU/mL. All strains were stored at 4 °C.

Disposable face masks

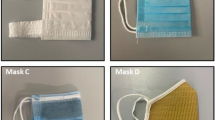

Three brands of disposable face mask were purchased and used for the investigation: an anti-droplet mask (Korean Filter [KF]-AD) and two safety face masks (KF80 and KF94) certified by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS, formerly known as the Korea Food & Drug Administration or KFDA). The KF-AD is a type of light mask for easy breathing and that prevents droplet inhalation. The KF80 and KF94 have filtration efficiencies of > 80% for 0.6 µm particles and > 94% for 0.4 µm fine particles (MFDS 2020). The KF94 is equivalent to the N95 respirator mask approved by the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and to FFP2 masks approved by the European standard (Park 2020). Each mask layer was optically analyzed using an optical microscope (Leica EZ4, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). These masks were cut into small pieces of 1 × 1 cm (Fig. 1A) and autoclaved prior to bacterial loading.

Optimization of adsorption solvent and absorption time

Adsorption solvent was determined by diluting stock solutions of Bacillus atrophaeus spores and E. coli (108 CFU/mL) in one of three different solvents to make 106 CFU/mL solution: deionized water, 40% ethanol, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, 20 µL each solution was loaded onto the mask pieces. Various adsorption durations were also examined to determine the optimized adsorption time. Bacillus atrophaeus spores and E. coli (106 CFU/mL, 20 µL) solutions were individually loaded onto the surface of the KF94 masks and allowed to dry in a biological safety cabinet (Labconco 4FT, Labconco Corp., Kansas, MO, USA) for up to 24 h.

Laser irradiation

Contaminated masks were treated using a 266 nm UV laser generated by second-harmonic generation of a 532 nm Nd:YVO4 laser (Lee et al. 2021). The laser beam was generated at an energy of 1.0 ± 0.3 W, a pulse width of 50 ns, a repetition rate of 120 kHz, diameter of 7 cm, speed of 5.0 ± 0.5 mm/s, and scan distance of 1 cm from a nanosecond pulsed laser AVIA 532–45 (Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The laser beam was able to move back and forth. A picture showing the laser irradiation process is displayed in Fig. 1B. Samples were irradiated by 1, 2, and 12 UV laser scans for 5, 10, and 60 s, respectively. Untreated spores on masks were prepared as controls. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

Measurement of bacterial survival

Bacillus atrophaeus and E. coli samples were released from the masks after a specified adsorption time or laser irradiation scan by mildly scratching the mask surface with pipette tips and repeated pipetting of 300 µL PBS with 0.02% Tween 20. Then, a portion (25 µL) of the detached solution was evenly smeared onto a nutrient-rich LB agar plate and incubated at 37 °C for 16–24 h. Viable colonies were counted in ImageJ, and CFU values were calculated. If the number of viable colonies was too high to count, dilution prior to incubation was performed. In the case of no viable colonies, CFU values were assigned as 1 (Yadav et al. 2004). To clearly display the change in the number of colonies, survival fraction was defined as below (Cortesao et al. 2020).

Survival fraction = N/N0.

N: mean CFU recovered from irradiated sample.

N0: mean CFU recovered from untreated sample.

Log10(survival fraction) is equal to –log10(N0/N), where log10(N0/N) is commonly known as log10(reduction) (Wood et al. 2019).

Particle filtration efficiency

A whole mask, approximately 210 × 80 mm, was irradiated with varying numbers of UV laser scans. Particle filtration efficiency was measured using a filter tester (DL-360F, Daelim Starlet Co., Ltd., Siheung-si, Republic of Korea) equipped with a sodium chloride (NaCl) generator for KF-AD and KF80 masks and a paraffin oil aerosol generator for KF94 masks. Average particle sizes for NaCl and paraffin oil aerosols are 0.6 μm and 0.4 μm, respectively. Aerosol flow rate was 95 L/min with a concentration of 8 ± 4 mg/m3 (NaCl) or 20 ± 5 mg/m3 (paraffin oil) passed over the masks. After 3 min, particle concentrations were recorded in 30 ± 3 s intervals between measurements. The particle filtration efficiency was calculated using the ratio of the particle concentration kept by masks (C1-C2) and initial particle amount (C1) as shown below.

P: Particle filtration efficiency.

C1: Pre-passage concentration of NaCl or paraffin oil.

C2: Post-passage concentration of NaCl or paraffin oil.

Results and discussion

Structure of the face mask layers

The structure of each mask type was examined using an optical microscope as shown in Fig. 2. KF-AD masks are composed of a non-woven fabric inner layer, a meltblown filter, and a spunbond outer layer. KF80 masks are composed of a polypropylene middle layer between two spunbond–meltblown–spunbond (SMS) layers. KF94 is a 4-ply mask with a spunbond outer layer, a meltblown filter, a thermal bonding middle layer, and an inner layer of non-woven fabric.

Optimization of adsorption conditions

Selection of adsorption solvent

The face masks are structurally composed of several stacked layers (Jung et al. 2020). Due to the hydrophobic nature of the mask layers, samples diluted in deionized water had difficulty binding to the mask surface (Li et al. 2006). Thus, the use of an alternative solvent was necessary.

To reduce the amount of water in the adsorption solvent, an aqueous ethanol solution was considered an alternative adsorption solvent. Although Bacillus spores are highly resistant to ethanol, the relative survival of Bacillus spores was significantly decreased after diluting them in solutions containing more than 50% ethanol (Lin et al. 2018). Therefore, 40% ethanol was used as a adsorption solvent for Bacillus atrophaeus spores. Use of this solvent caused gradual absorption of spores into the mask layers. By contrast, even low concentrations of ethanol have adverse effects on the viability of E. coli particles (Elzain et al. 2019; Horinouchi et al. 2010). Thus, PBS was used to dilute E. coli. In contrast to deionized water, PBS was more easily adsorbed into the layers.

Selection of adsorption time

Bacillus spores are resistant to stress and have a long survival time on surfaces (Brosseau et al. 1997; Setlow 2006), while E. coli survival drastically decreases after 8 h on respirators (Lin et al. 2017). Water loss from long-term storage may damage the cell membrane and lead to protein misfolding and detrimental effects on nucleic acids and lipids (Billi et al. 2002), thus interfering with the viability of E. coli following culture. To determine the optimum adsorption duration for Bacillus spores and E. coli, the bacteria were detached and cultured to obtain the survival fraction. In the medium of LB agar, Bacillus spores after incubation form circular, light-orange colonies (Gibbons et al. 2011). Meanwhile, E. coli colonies are off-white with a shiny texture (Son et al. 2012).

There were no significant differences in the viability of Bacillus atrophaeus spores (106 CFU/mL, 20 µL) loaded on the KF94 respirator masks up to 24 h (Fig. 3). The log10(survival fraction) was − 0.10 after 30 min and around − 0.28 from 2 to 24 h. E. coli (106 CFU/mL, 20 µL) showed a significant reduction in survival fraction with increasing adsorption duration time where the log10(survival fraction) was − 0.50 after 3 h adsorption and significantly decreased to − 2.23 after 4 h adsorption. The values further decreased to − 3.12 and − 4.05 after 8 and 24 h, respectively. Although the adsorption duration up to 24 h on face masks did not result in any adverse effect on viability of Bacillus spores, a notable reduction of E. coli was observed after 3 h. Therefore, we investigated the effect of UV laser irradiation in masks treated with Bacillus spores after drying overnight (16 h), and masks treated with E. coli after 2 h adsorption.

Measurement of bacterial survival

To investigate the sterilization effect of UV laser irradiation, bacterial samples were adsorbed on the masks for 16 h (Bacillus spores) and 2 h (E. coli). After exposure to the UV laser, bacterial samples were detached and cultured to determine remaining viability. Figure 4A shows the log10(survival fraction) of Bacillus atrophaeus spores. Treatment with the UV laser led to a log10(survival fraction) of − 3.71, − 3.65, and − 3.74 corresponding to KF-AD, KF80, and KF94 masks after 1 scan. Increasing the number of UV laser scans led to increased inactivation of bacterial particles, with a log10(survival fraction) of − 3.91, − 3.85, and − 3.89 for KF-AD, KF80, and KF94 masks, respectively, after 2 and 12 scans. In masks treated with E. coli, only 1 UV laser scan was needed for complete inactivation of KF-AD, KF80, and KF94 masks with log10(survival fraction) of − 3.45, − 3.72, and − 3.42, respectively (Fig. 4B). Because E. coli is vulnerable to dehydration, it is also more sensitive to UV laser than bacterial spores.

Decreased bacterial viability was similar between the different types of face mask, suggesting that the number of layers and type of material do not impact the effectiveness or penetration of the UV laser.

Particle filtration efficiency

To investigate whether UV laser irradiation would decrease the performance of the face masks, we measured the particle filtration efficiency of NaCl and paraffin oil aerosols before and after UV laser irradiation. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the masks demonstrated a high filtration efficiency (of 76.4%, 85.9%, and 95.5% for KF-AD, KF80, and KF94, respectively). After irradiation, KF94 masks retained a 95% filtration efficiency against paraffin oil filtration. The NaCl filtration efficiency decreased slightly after irradiation for the KF80 and KF-AD masks at 84.3% and 81.0% after 12 laser scans. Therefore, the physical characteristics of the three masks were not significantly affected by UV laser irradiation up to 12 scans.

The deterioration of particle filtration efficiency from sterilization treatments has been a limiting factor in the ability to reuse masks. Although alcohol solutions are effective at removing attached bacteria, they also reduce filtration performance (Kim et al. 2009; Ullah et al. 2020). Washing masks with or without detergent can also destroy filter integrity (Jung et al. 2020; Viscusi et al. 2007). Conversely, while UV irradiation-based treatment does not impact filtration efficiency, there is incomplete sterilization against E. coli (Jung et al. 2020). There are some limitations of using 266 nm pulsed laser for general purpose due to its high cost, high energy consumption, and trained operator requirement. The current results, however, show that UV laser irradiation could be used as alternative sterilization method for face masks in regard to both Bacillus spores and E. coli. Further research of UV laser irradiation is needed to include face mask components such as straps and metal nose clips.

Conclusions

Irradiation with a Nd:YVO4 laser (266 nm, 1 W) is an effective sterilization method against both Bacillus atrophaeus spores and non-spore-forming bacteria of E. coli contaminating three different kinds of safety face mask (KF-AD, KF80, and KF94). The particle filtration efficiency was successfully preserved after UV laser irradiation regardless of the type of investigated material.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Armstrong GL, Hollingsworth J, Morris JG Jr. Emerging foodborne pathogens: Escherichia coli O157:H7 as a model of entry of a new pathogen into the food supply of the developed world. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18:29–51.

Aronson AI, Beckman W, Dunn P. Bacillus thuringiensis and related insect pathogens. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:1–24.

Banerjee R, Roy P, Das S, Paul MK. A hybrid model integrating warm heat and ultraviolet germicidal irradiation might efficiently disinfect respirators and personal protective equipment. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:309–18.

Billi D, Potts M. Life and death of dried prokaryotes. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:7–12.

Brosseau LM, McCullough NV, Vesley D. Bacterial survival on respirator filters and surgical masks. Appl Biosaf. 1997;2:32–43.

Celina MC, Martinez E, Omana MA, Sanchez A, Wiemann D, Tezak M, Dargaville TR. Extended use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic - thermal conditioning and spray-on surface disinfection. Polym Degrad Stab. 2020;179: 109251.

Cortesao M, de Haas A, Unterbusch R, Fujimori A, Schutze T, Meyer V, Moeller R. Aspergillus niger spores are highly resistant to space radiation. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:560.

Cramer AK, Plana D, Yang H, Carmack MM, Tian E, Sinha MS, Krikorian D, Turner D, Mo J, Li J, Gupta R, Manning H, Bourgeois FT, Yu SH, Sorger PK, LeBoeuf NR. Analysis of SteraMist ionized hydrogen peroxide technology in the sterilization of N95 respirators and other PPE. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2051.

DeAngelis HE, Grillet AM, Nemer MB, Wasiolek MA, Hanson DJ, Omana MA, Sanchez AL, Vehar DW, Thelen PM. Gamma radiation sterilization of N95 respirators leads to decreased respirator performance. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0248859.

Derraik JGB, Anderson WA, Connelly EA, Anderson YC. Rapid Review of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 viability, susceptibility to treatment, and the disinfection and reuse of PPE, particularly filtering facepiece respirators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176117.

Doyle MP. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its significance in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:289–301.

Elzain AM, Elsanousi SM, Ibrahim MEA. Effectiveness of ethanol and methanol alcohols on different isolates of staphylococcus species. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1605(91)90143-D.

Gibbons HS, Broomall SM, McNew LA, Daligault H, Chapman C, Bruce D, Karavis M, Krepps M, McGregor PA, Hong C, Park KH, Akmal A, Feldman A, Lin JS, Chang WE, Higgs BW, Demirev P, Lindquist J, Liem A, Fochler E, Read TD, Tapia R, Johnson S, Bishop-Lilly KA, Detter C, Han C, Sozhamannan S, Rosenzweig CN, Skowronski EW. Genomic signatures of strain selection and enhancement in Bacillus atrophaeus var. globigii, a historical biowarfare simulant. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17836.

Horinouchi T, Tamaoka K, Furusawa C, Ono N, Suzuki S, Hirasawa T, Yomo T, Shimizu H. Transcriptome analysis of parallel-evolved Escherichia coli strains under ethanol stress. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:579.

Hossain MS, Nik Ab Rahman NN, Balakrishnan V, Alkarkhi AF, Ahmad Rajion Z, Ab Kadir MO. Optimizing supercritical carbon dioxide in the inactivation of bacteria in clinical solid waste by using response surface methodology. Waste Manag. 2015;38:462–73.

Jang H, Nguyen M-C, Noh S, Cho WK, Sohn Y, Yee K, Jung H, Kim J. UV laser sterilization of Bacillus atrophaeus spores on ceramic tiles. Ceram Int. 2022;48:1446–50.

Jung S, Hemmatian T, Song E, Lee K, Seo D, Yi J, Kim J. Disinfection treatments of disposable respirators influencing the bactericidal/bacteria removal efficiency, filtration performance, and structural integrity. Polymers (basel). 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13010045.

Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–40.

Kayani BJ, Weaver DT, Gopalakrishnan V, King ES, Dolson E, Krishnan N, Pelesko J, Scott MJ, Hitomi M, Cadnum JL, Li DF, Donskey CJ, Scott JG, Charnas I. UV-C tower for point-of-care decontamination of filtering facepiece respirators. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49:424–9.

Kim J, Hinestroza JP, Jasper W, Barker RL. Effect of solvent exposure on the filtration performance of electrostatically charged polypropylene filter media. Text Res J. 2009;79:343–50.

Lee S-Y, Jang D-I, Kim D-Y, Yee K-J, Nguyen H-Q, Kim J, Sohn Y, Jung H. UV laser decontamination of chemical warfare agent simulants CEPS and malathion. J Photochem Photobiol, A. 2021;406: 112989.

Li Y, Wong T, Chung J, Guo YP, Hu JY, Guan YT, Yao L, Song QW, Newton E. In vivo protective performance of N95 respirator and surgical facemask. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49:1056–65.

Lin T-H, Tang F-C, Chiang C-H, Chang C-P, Lai C-Y. Recovery of bacteria in filtering facepiece respirators and effects of artificial saliva/perspiration on bacterial survival and performance of respirators. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2017;17:187–97.

Lin TH, Tang FC, Hung PC, Hua ZC, Lai CY. Relative survival of Bacillus subtilis spores loaded on filtering facepiece respirators after five decontamination methods. Indoor Air. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12475.

Lindsley WG, Martin SB Jr, Thewlis RE, Sarkisian K, Nwoko JO, Mead KR, Noti JD. Effects of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) on N95 respirator filtration performance and structural integrity. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2015;12:509–17.

Manges AR, Johnson JR, Foxman B, O’Bryan TT, Fullerton KE, Riley LW. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1007–13.

McEvoy B, Rowan NJ. Terminal sterilization of medical devices using vaporized hydrogen peroxide: a review of current methods and emerging opportunities. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;127:1403–20.

MFDS, The types of MFDS-regulated Masks, Diagnostics Devices, MFDS-regulated Mask Information, 2020, https://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/brd/m_65/view.doseq=11&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&multi_itm_seq=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=2.

Nguyen MCT, Nguyen H-Q, Jang H, Noh S, Lee S-Y, Jang K-S, Lee J, Sohn Y, Yee K, Jung H, Kim J. Sterilization effects of UV laser irradiation on Bacillus atrophaeus spore viability, structure, and proteins. Analyst. 2021;146:7682–92.

Oh C, Araud E, Puthussery JV, Bai H, Clark GG, Wang L, Verma V, Nguyen TH. Dry heat as a decontamination method for n95 respirator reuse. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2020;7:677–82.

Paramita RI, Nelwan EJ, Fadilah F, Renesteen E, Puspandari N, Erlina L. Genome-based characterization of Escherichia coli causing bloodstream infection through next-generation sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0244358.

Park SH. Personal protective equipment for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Chemother. 2020;52:165–82.

Pascoe MJ, Robertson A, Crayford A, Durand E, Steer J, Castelli A, Wesgate R, Evans SL, Porch A, Maillard JY. Dry heat and microwave-generated steam protocols for the rapid decontamination of respiratory personal protective equipment in response to COVID-19-related shortages. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:10–9.

Paul D, Gupta A, Maurya AK. Exploring options for reprocessing of N95 filtering facepiece respirators (N95-FFRs) amidst COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0242474.

Post KW. Overview of Bacteria. In Diseases of Swine. 2019. p. 743–748.

Rodriguez-Martinez CE, Sossa-Briceno MP, Cortes JA. Decontamination and reuse of N95 filtering facemask respirators: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:1520–32.

Setlow P. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:514–25.

Son MS, and Taylor RK. Growth and maintenance of Escherichia coli laboratory strains. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2012;Chapter 5:Unit 5A 4.

Spotts Whitney EA, Beatty ME, Taylor TH Jr, Weyant R, Sobel J, Arduino MJ, Ashford DA. Inactivation of Bacillus anthracis spores. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:623–7.

Stenfors Arnesen LP, Fagerlund A, Granum PE. From soil to gut: Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:579–606.

Ullah S, Ullah A, Lee J, Jeong Y, Hashmi M, Zhu C, Joo KI, Cha HJ, Kim IS. Reusability comparison of melt-blown vs nanofiber face mask filters for use in the coronavirus pandemic. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2020;3:7231–41.

Viscusi DJ, King WP, Shaffer RE. Effect of decontamination on the filtration efficiency of two filtering facepiece respirator models. J Int Soc Respir Prot. 2007;24:93.

Viscusi DJ, Bergman MS, Eimer BC, Shaffer RE. Evaluation of five decontamination methods for filtering facepiece respirators. Ann Occup Hyg. 2009;53:815–27.

Wood JP, Adrion AC. Review of Decontamination techniques for the inactivation of Bacillus anthracis and other spore-forming bacteria associated with building or outdoor materials. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:4045–62.

Yadav RKP, Halley JM, Karamanoli K, Constantinidou HI, Vokou D. Bacterial populations on the leaves of Mediterranean plants: quantitative features and testing of distribution models. Environ Exp Bot. 2004;52:63–77.

Zhao X, You F. Waste respirator processing system for public health protection and climate change mitigation under COVID-19 pandemic: novel process design and energy, environmental, and techno-economic perspectives. Appl Energy. 2021;283: 116129.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Defense Acquisition Program Administration and Agency for Defense Development under the contract UD180050GD.

Funding

Funding was provided by Defense Acquisition Program Administration and Agency for Defense Development under the contract UD180050GD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN involved in conceptualization, methodology, data curation, visualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft, and reviewing. HN participated in methodology and data curation. HJ took part in methodology and data curation. SN involved in methodology and data curation. YS participated in supervision, conceptualization, and reviewing. KY took part in supervision, conceptualization, reviewing, and funding acquisition. HJ took part in supervision, project administration, conceptualization, reviewing, and funding acquisition. JK involved in supervision, conceptualization, validation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing and editing, and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, MC., Nguyen, HQ., Jang, H. et al. Effective inactivation of Bacillus atrophaeus spores and Escherichia coli on disposable face masks using ultraviolet laser irradiation. J Anal Sci Technol 13, 23 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-022-00332-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40543-022-00332-7