Abstract

Background

Cashew nut shell is a by-product of cashew (Anacardium occidentale) production, which is abundant in many developing countries. Cashew nut shell liquor (CNSL) contains a functional chemical, cardanol, which can be converted into a hydroxyoxime. The hydroxyoximes are expensive reagents for metal extraction.

Methods

CNSL-based oxime was synthesized and used to extract Ni, Co, and Mn from aqueous solutions. The extraction potential was compared against a commercial extractant (LIX 860N).

Results

All metals were successfully extracted with pH0.5 between 4 and 6. The loaded organic phase was subsequently stripped with an acidic solution. The extraction efficiency and pH0.5 of the CNSL-based extractant were similar to a commercial phenol-oxime extractant. The metals were stripped from the loaded organic phase with a recovery rate of 95% at a pH of 1.

Conclusions

Cashew-based cardanol can be used to economically produce an oxime in a simple process. The naturally-based oxime has the economic potential to sustainably recover valuable metals from spent lithium-ion batteries.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Solvent extraction is commonly used in hydrometallurgical processes to separate the desired metal from aqueous solutions. With the use of careful pH control and a series of selective extraction and stripping stages, the separation of multiple desirable streams can be achieved [1]. Solvent extraction is considered a lower cost and more environmentally friendly option than traditional pyrometallurgical processes [2]. In addition to mineral production, solvent extraction is also used in metal recycling. Currently, the recycling process of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) and many types of electronic waste relies on solvent extraction [3].

With the increasing demand for LIBs and the high production of electronic waste, there is an urgent need for effective recycling both to recover valuable materials and for more environmentally acceptable disposal. While LIBs recycling facilities are available in developed countries, economic feasibility remains a challenge. These facilities are only available in countries with strict LIB regulations [3]. On the other hand, wastes from developed countries are often shipped to developing countries for processing and disposal. According to a CSIRO report, only 2% of Australian spent LIBs were recycled, whereas the majority of the remainder was shipped overseas [4]. LIBs’ disposal in landfills can cause severe ecological and health damages [3]. Recycling of many types of e-waste faces similar challenges [5]. The lack of recycling facilities is a particularly pressing issue for developing countries with weak environmental regulations. Recycling metals, especially nickel and cobalt, avoid associated environmental impacts from the mining activities [6] and provides a method to recover valuable materials.

These problems show an urgent need to develop an economical and practical process with potential application for localized or small-scale collection and recycling facilities. To facilitate this, a move away from industrial chemicals, which are effective but expensive, is needed. In addition to affordable costs, the chemicals should have lower toxicity and lower risks in handling and transportation. For instance, organic and less hazardous acids, citric acid [7], malic acid [8], and oxalic acid [9], have been used in leaching processes.

The extractant is the most specialized and expensive chemical among the required reagents for the processes [10]. Commonly used extractants are based on either a hydroxyoxime group [10] (such as the Acorga and LIX series) or phosphonic groups (Cyanex series) [11, 12], although a wide variety exists for specific metal selectivity. The extractants are often made from petrochemicals. For instance, the hydroxyoximes are synthesized via several reaction steps such as oligomerisation and oximation [13]. The solvents (diluent) and extractants in current use represent a high operating cost alongside the generation of hazardous (organic) waste [14].

In this study, we utilize a natural-based chemical in extracting metals from LIBs. The chemical is made from natural cardanol, which is an alkyl-phenol found in the cashew nut shell liquor (CNSL) [15]. The cashew tree (Anacardium occidentale) is a native of Brazil and the Lower Amazons [16]. The tree is a valuable cash crop in tropical parts of Africa and Asia (Fig. 1a). The cashew nut shell (Fig. 1b) is a by-product of cashew processing and is typically treated as a waste stream. CNSL contains a high fraction of cardanol (Fig. 1c), up to wt. 25% [15]. It should be noted that the CNSL cardanol contains a 15-carbon chain in the alkyl branch, whereas most industrial alkylphenols have 12 or fewer carbons [17]. Furthermore, the CNSL cardanol has the hydrocarbon chain situated in the meta-position (Fig. 1c), which is distinct from most synthesized alkyl phenols [15]. The CNSL cardanol thus creates an oxime where the hydrocarbon chain is in the meta-position relative to the phenol group, as (Fig. 1d) distinct from the overwhelming majority of reported oxime-type extractants (including the common ACORGA and LIX series) which have an ortho-structure (Fig. 1e) [18]. The underlying reason is that industrial oligomerisation tends to form ortho- and para-alkyl-phenol only [13].

Previously, we synthesized an oxime from CNSL and successfully used it to extract gallium from bauxite processing liquor [19]. This study explores the feasibility of the chemical to extract valuable metal from recycling LIBs and e-waste. Among the current LIBs, Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC) is the most common cathode due to its high capacity [20]. Consequently, the extraction of the natural-based extractants with three divalent metals, Ni2+, Co2+ and Mn2+, is investigated. Among a myriad of structures, complexes between phenolic oxime extractants and a large number of transition metals, including vanadium, nickel, cobalt, copper, platinum, and palladium, have been reported [18], which is promising for their use in recovering valuable metals as part of the recycling process. Ultimately, this study aims to provide an economical and environmental friendly extractant for LIBs’ recycling.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization of CNSL-oxime

Cardanol was received from a cashew nut shell processing facility in Binh Phuoc Province, Vietnam. Cardanol was dissolved in triethylamine (volume ratio 3:2). The cardanol solution was stirred for 30 min and added to a mixture of SnCl4 and toluene (SnCl4:toluene volume ratio of 1:4) at the volume ratio of 1:1. The solution was stirred for 30 min before adding a mixture of formaldehyde and methanol (formaldehyde to methanol volume ratio of 3:2). This solution was stirred constantly for 24 h at 25 °C. The resulting alkyl salicylaldehyde product was rinsed and filtered using toluene and deionized water.

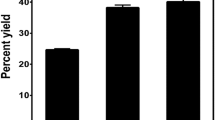

The recovered alkyl salicylaldehyde was employed for the oximisation reaction (step 2 in Fig. 2). Alkyl salicylaldehyde was dissolved into deionized water (1:1 weight ratio), mixed with the same amount of hydroxylamine hydrochloride, and stirred for 30 min. A mixture constituting triethylamine and methanol (trimethylamine to methanol volume ratio of 1:2) was added into the solution to start the oximisation reaction [21]. The reaction was maintained for 6 h at 25 °C under constant stirring (at 200 rpm). The final oxime product was filtered and heated at 80 °C for 30 h to remove the organic solvent.

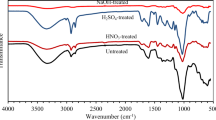

The intermediate (alkyl salicylaldehyde) and final (oxime) products were diluted in toluene at 5% for IR characterization (Spectrum Two PerkinElmer). The IR spectra are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The characteristic bands of the aldehyde group are clearly identified in Fig. 3: 1607 cm−1 (C=O bond) and three peaks in the range 3033–2882 cm−1 (C–H bonds). The characteristic bands of the oxime group were confirmed in Fig. 4: 1643 cm−1 (C=N–OH bond) and 3418 cm−1 (O–H bond).

Chemicals for extractant study

In addition to the CNSL-based oxime, 5-nonylsalicylaldoxime (LIX 860N-IC) was received from BASF Ltd. (Australia). Table 1 presents a list of metal compounds employed in the extraction study. All chemicals were obtained from Chem-Supply (Australia) and used as received, without any further purification.

Solvent extraction procedures

The aqueous solution was prepared by dissolving the exact amount of MnSO4·H2O, CoSO4·7H2O, and NiSO4·6H2O with the Mn:Co:Ni molar ratio of 1:1:1 in doubly distilled water. The organic phase was prepared by mixing extractant and kerosene (a mixture of CnH2n+2 with n between 10 and 16). The volumetric ratio between extractant solution (both LIX 860N-IC and natural oxime) and kerosene was 1:9. The extraction and stripping processes were performed by mechanically contacting equal volumes (100 mL) of aqueous and organic solutions in a separating funnel. To generate the pH extraction equilibrium, a 3 M NaOH solution was employed to adjust the pH of the aqueous–organic mixture. Such pH values of the aqueous–organic mixture or emulsion were continuously measured with an intermediate junction pH electrode (Ionode, IJ-44A) connected to a pH meter. After each addition of NaOH into the mixture, the separating funnel was shaken for 10 min using Separatory Funnel Shaker (SR-2DW, Borg Scientific) and followed by its equilibrium at each sample point until the pH was stable to two decimal points.

The loaded organic phase obtained from the extraction experiments was used for the stripping experiment. The loaded organic was contacted with deionized water at a volume ratio of 1:1. Acidic solution (5 wt. % of sulphuric acid) was added to adjust the pH of the mixture. The stripping equilibrium was established with a similar procedure of the extraction experiment, that is shaken for 10 min and allowed to separate.

The collected aqueous sample was digested with a 5% HNO3 solution and analyzed by employing ICP-OES equipment (NexION™ 350D-Optima 8300, PerkinElmer). All measurement was performed at room temperature and in triplicate.

Results and discussion

The metal loading (oil phase percentage, E) of each metal was evaluated by the following equation:

where \(\left[ {\text{M}} \right]_{0}\) and \(\left[ {\text{M}} \right]_{{\text{e}}}\) (mg L−1) are the initial and equilibrium metal concentration in the aqueous phase, respectively; V0 and Ve (mL) are the initial and equilibrium volumes of the aqueous phase, respectively.

The extraction and stripping isotherms of the CNSL-based extractant and commercial (LIX series) extractant are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. As expected, the metals are transferred to the oil phase at higher pH and transferred to the aqueous phase at low pH. The pH-dependent behavior is consistent with the photon ionization of oxime at a high pH [10]. The commercial and naturally based oximes were shown to have similar extracting and stripping capacities. While the CNSL-based molecule has 15 carbons in the hydrocarbon chain, against the nine-carbon chain in LIX 860N-IC, it also has three double bonds. In addition, the 15-carbon “tail” is in the meta- (rather than ortho-) orientation to the phenol group. The length of the carbon chain can impact the hydrophobicity of the extractant and complexes [13]. A short carbon chain can increase water solubility, and reduce loading efficiency and phase separation. A longer carbon chain, in contrast, decreases solubility and hinders the stripping process. However, there is no noticeable impact of the molecular structure on the extraction capacity in this instance. The natural-based extractant can extract all three metals within the intermediate pH range, indicating that the change in hydrophobicity is too weak to have a significant impact on the loading and stripping processes. Both the commercial (LIX) and CNSL-based extractant show similar equilibrium curves for the three metals (Ni, Co and Mn) due to the complex formation of the oxime group [10]. Conversely, both extractants can collect the three metals at an intermediate pH, making them practical choices for generating a combined product that can be sent off-site to another refinery for further processing.

a Extraction equilibrium and b stripping equilibrium of CNSL-based oxime [lines represents fitting according to Eq. (2)]

a Extraction equilibrium and b stripping equilibrium of LIX (lines represents fitting according to Eq. (2))

The data were fitted with Gaussian distribution by an error function (error f):

where pH0.5 is the equilibrium pH (at which the metal ion is present equally in the two phases), and δ is the width of the distribution.

The error function is a well-accepted model for probability theory and given by [22]

The fitting data are tabulated in Table 2.

The results demonstrate the potential of CNSL to recover Ni, Mn, and Co as part of the recycling process. Most of the existing LIBs recycling aims to recover cobalt [3], the most valuable metal in the cathode. However, battery manufacturers tend to increase nickel content to improve capacity [23, 24]. For instance, the LIBs for electric vehicles are now relying on NMC 622 (60% Ni, 20% Mn, and 20% Co) [25] and NMC 811 [20]. Consequently, a recycling facility should recover both Ni and Co. In comparison with these two metals, Mn has a lower economic value and is often a nuisance in Ni–Co production [26]. The natural-based extractant allows the recovery of the metals that could then be sent as a crystalline or matte product for further processing and recovery.

It is important to highlight that CNSL is an abundant by-product in many developing countries in Asia, Africa, and South America [27]. These developing countries can effectively utilize natural resources for metal recovery. The current price of CNSL is around US $300–400 per tonne, and it is often used as fuel. The synthesizing agents required for the production of the oxime are common chemicals. The overall cost of synthesized oxime is estimated ~ US $2000–3000 per tonne, which is about 20% of the current price of the industrial oxime. In addition to being low cost, the natural oxime has a low carbon footprint and significantly reduces the environmental impact of LIBs’ recycling [28].

Conclusions

A natural-based extractant was synthesized from cashew nut shell liquor and used to extract a mixture of metals from an aqueous solution. It was found that the product has a similar extraction potential as a commercial oxime. The natural chemical is abundant in many developing countries and could be used for economically reclaiming valuable metals from spent batteries.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Cheng CY, Barnard KR, Zhang W, Robinson DJ. Synergistic solvent extraction of nickel and cobalt: a review of recent developments. Solvent Extr Ion Exch. 2011;29:719–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/07366299.2011.595636.

Bartos PJ. SX-EW copper and the technology cycle. Resour Policy. 2002;28:85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4207(03)00025-4.

Winslow KM, Laux SJ, Townsend TG. A review on the growing concern and potential management strategies of waste lithium-ion batteries. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2018;129:263–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.11.001.

King S, Boxall NJ, Bhatt AI. Lithium battery recycling in Australia—current status and opportunities for developing a new industry. J Clean Prod. 2018;215:1279–87.

Islam A, Ahmed T, Awual MR, et al. Advances in sustainable approaches to recover metals from e-waste—a review. J Clean Prod. 2020;244:118815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118815.

Schmidt T, Buchert M, Schebek L. Investigation of the primary production routes of nickel and cobalt products used for Li-ion batteries. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2016;112:107–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.04.017.

Li L, Zhai L, Zhang X, et al. Recovery of valuable metals from spent lithium-ion batteries by ultrasonic-assisted leaching process. J Power Sources. 2014;262:380–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.04.013.

Musariri B, Akdogan G, Dorfling C, Bradshaw S. Evaluating organic acids as alternative leaching reagents for metal recovery from lithium ion batteries. Miner Eng. 2019;137:108–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2019.03.027.

Zeng X, Li J, Shen B. Novel approach to recover cobalt and lithium from spent lithium-ion battery using oxalic acid. J Hazard Mater. 2015;295:112–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.02.064.

Wilson AM, Bailey PJ, Tasker PA, et al. Solvent extraction: the coordination chemistry behind extractive metallurgy. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:123–34. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cs60275c.

Kang J, Senanayake G, Sohn J, Shin SM. Recovery of cobalt sulfate from spent lithium ion batteries by reductive leaching and solvent extraction with cyanex 272. Hydrometallurgy. 2010;100:168–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2009.10.010.

Mantuano DP, Dorella G, Elias RCA, Mansur MB. Analysis of a hydrometallurgical route to recover base metals from spent rechargeable batteries by liquid–liquid extraction with Cyanex 272. J Power Sources. 2006;159:1510–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2005.12.056.

Szymanowski J. Hydroxyoximes and copper hydrometallurgy. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1993.

Vahidi E, Zhao F, et al. Life cycle analysis for solvent extraction of rare earth elements from aqueous solutions. In: Kirchain RE, Blanpain B, Meskers C, et al., editors. REWAS 2016: towards materials resource sustainability. Cham: Springer; 2016. p. 113–20.

Vasapollo G, Mele G, Del Sole R. Cardanol-based materials as natural precursors for olefin metathesis. Molecules. 2011;16:6871–82. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16086871.

Akinhanmi TF, Atasie VN. Chemical composition and physicochemical properties of cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale) oil and cashew nut shell liquid. J Agric Food Environ Sci. 2008;2:1–10.

Lorenc, J.F., Lambeth, G. and Scheffer, W. (2003). Alkylphenols. In Kirk-Othmer (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471238961.0112112512151805.a01.pub2.

Smith AG, Tasker PA, White DJ. The structures of phenolic oximes and their complexes. Coord Chem Rev. 2003;241:61–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00310-7.

Hoang AS, Nguyen HN, Quoc Bui N, et al. Extraction of gallium from Bayer liquor using extractant produced from cashew nutshell liquid. Miner Eng. 2015;79:88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2015.05.012.

Xuan W, Otsuki A, Chagnes A. Investigation of the leaching mechanism of NMC 811 (LiNi0·8Mn0.1Co0.1O2) by hydrochloric acid for recycling lithium ion battery cathodes. RSC Adv. 2019;9:38612–8. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ra06686a.

Hoang AS, Tran TH, Nguyen HN, et al. Synthesis of oxime from a renewable resource for metal extraction. Korean J Chem Eng. 2015;32:1598–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-014-0348-0.

Andrews LC. Special functions of mathematics for engineers. Bellingham: SPIE; 1998.

Kasnatscheew J, Röser S, Börner M, Winter M. Do increased Ni contents in LiNi xMn yCo zO2 (NMC) electrodes decrease structural and thermal stability of Li ion batteries? A thorough look by consideration of the Li+ extraction ratio. ACS Appl En Mater. 2019;2:7733–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.9b01440.

Xi Z, Wang Z, Yan G, et al. Hydrometallurgical production of LiNi 0.80Co0.15Al 0.05 O 2 cathode material from high-grade nickel matte. Hydrometallurgy. 2019;186:30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2019.03.007.

Lipson AL, Durham JL, LeResche M, et al. Improving the thermal stability of NMC 622 Li-ion battery cathodes through doping during coprecipitation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:18512–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c01448.

Zhang W, Cheng CY, Pranolo Y. Investigation of methods for removal and recovery of manganese in hydrometallurgical processes. Hydrometallurgy. 2010;101:58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2009.11.018.

Dendena B, Corsi S. Cashew, from seed to market: a review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2014;34:753–72.

Liang Y, Su J, Xi B, et al. Life cycle assessment of lithium-ion batteries for greenhouse gas emissions. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2017;117:285–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.08.028.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by the Regional Collaboration Programme, Australian Academy of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMP, SAH, and SY designed the study. SAH and SHV. synthesized the oxime. HMN, CVN and AEH measured the extraction. The manuscript was written through the contributions of all the authors. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Phan, C.M., Hoang, S.A., Vu, S.H. et al. Application of a cashew-based oxime in extracting Ni, Mn and Co from aqueous solution. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 8, 37 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-021-00236-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-021-00236-5