Abstract

Entrepreneurship is a tool for facilitating rural economic development, which is becoming increasingly needed to respond to the growing impacts of accelerating climate change on rural women’s livelihoods in less developed countries creating constraints on sustainable development. This study examines the awareness of and impacts of climatic changes as perceived by women in South West Nigeria in diverse vegetation zones. It elicits the challenges facing women and which constrain their entrepreneurial activities. It therefore identifies potential adaptation strategies and opportunities, including drawing on a review of wider developments in at international development level, such as technological, institutional and infrastructural innovations. The study employed explorative, mixed approaches, including quantitative and qualitative methods. Five hundred and ninety-five questionnaires were administered to selected respondents through multi-stage sampling technique, while Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) were used to solicit qualitative data from two hundred and forty women. Quantitative data were analysed with SPSS for descriptive and analysis of variance, and Atlas ti. was used to thematically analyse qualitative data.

Findings showed that women have high levels of awareness of changes in their climate. Analysis of variance revealed that most of the women involved in crop farming in the vegetation zones showed better understanding than women in other livelihood. They strongly agreed (with mean of approximately 5) that climate change had greatly affected soil fertility, caused less predictable, and prolonged the dry season. Over 90% of the women perceived significant impacts of these changes on their livelihood activities. Overall, there were no clear divergences in women’s attitudes towards innovation and entrepreneurship between the vegetation zones and a relatively high expectation of government support. Wider review of current practice and innovations highlights a wide range of new opportunities for building women’s adaptive capacity which could directly or indirectly catalyse increased entrepreneurship amongst women. Furthermore, the involvement of local authorities and community-based organisations, as well as diverse public and private actors, in the development of adaptation strategies is crucial to achieving this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a critical tool for socio-economic development (UNCTAD 2005). Given the challenges and impacts of the changing climate on rural peoples, including disproportionate gendered impacts, there are now growing public, private and civil society efforts to respond through adaptation policy-making and programming. While the role of entrepreneurship in promoting rural development and women’s economic empowerment has been widely discussed, the gender-entrepreneurship-climate nexus has been neglected to date. This paper explores the potential opportunities associated with women’s entrepreneurship for improving adaptation responses to the changing climate and multiple rural stressors.

Climate change is accelerating (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or IPCC, 2014). Climate change issues will continue to be a frontline issue around the world, because even if it were possible to completely halt Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emission (IPCC 2007; Adesina & Odekunle 2011), an enormous volume of GHGs has been pumped into the atmosphere over the past two to three centuries and so we are committed to changes to the climate, no matter the mitigation strategies adopted now. If the current trajectory of increasing greenhouse gas emissions is not changed very soon, the effects of global warming will “spiral out of control.” This will bring about more natural disasters, worsen global food supply and threaten the existence of millions of people, with a disproportionately high impact on the impoverished and indigenous populations. Therefore, there is a need to continue to pursue climate change mitigation and adaptation with vigour (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014).

Climate change has significant implications for rural development and agriculture in developing countries. The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) stated that while 75% of the world’s 1.2 billion poor live and work in rural areas (IFAD, 2001), 50% of the developing-countries’ rural population were smallholders (farming 3 ha or less of crop land), and about 25% were landless (which may include some agricultural laborers, non-pastoralist livestock farmers, and non-agricultural based livelihoods). In the West and Southern African and Pacific countries, smallholder farmers cultivate excess of 70% arable and permanent cropland. In Nigeria, they are responsible for cultivating about 90% of rice, wheat, other food crops, cocoa, and cotton (Morton, 2007).

In the space of the 55 years between 1960 and 2015, the percentage of rural population to the total population in Nigeria has decreased from 84.59% in 1960 to 52.22% in 2015. However, in absolute figures, the rural population has increased from about 38.2 million in 1960 to about 95.2 million in 2015, which is approximately an 100% increment (UNDESA, 2015). This indicates that a large population of rural dwellers exist – all of whom are likely to be affected or have already been affected by the changing climate. Improving support for climate change adaptation is thus a policy imperative around the world, including in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Climate change impacts threaten rural livelihoods, especially among rural women. Both now, and over the long run, climate change and variability threatens to affect customary livelihood strategies and restrict the development of human potentials (Kronik & Verner, 2010). Studies have shown that rural women in developing countries are more vulnerable to climate change as they possess low adaptive capacity (Davies, et al., 2009; Oxfam, 2010). Rural dwellers, especially women across developing countries already perceive and experience negative effects of climate change and variability in all aspects, especially their livelihood practices (Hall & Patrinos, 2006); Akinbami, et al. 2015). As a result, it is increasingly important to empower rural women, alongside with other vulnerable groups like the children and the elderly, to help them to cope with the pressure of climate change and or make their livelihoods more resilient (Ogujiuba, 2014).

Climate change impacts are also felt at the national level, in terms of the economy. According to the World Bank classification (World Bank, 2010), the Nigerian economy is typical of a developing one in the lower-middle income category. Despite various reforms, the productive base of the economy remains weak, narrow and externally-oriented with primary production activities of agriculture and mining and quarrying (including crude oil and gas) accounting for about 65% of the real gross output and over 80% of government revenues (National Planning Commission, 2009). In addition, primary production activities account for over 90% of foreign exchange earnings and 75% of employment. Climate change is a threat to poverty reduction and economic growth especially in the rural areas, and it may wipe out many of the development gains made in last couple of decades, without major investment in adaptation responses as well as in mitigation efforts.

Supporting capacity strengthening of rural women in terms of their adaptive capacity will therefore, not only benefit rural women and communities, but has the potential to strengthen the effectiveness of climate change response measures nationally, promoting improved economic wellbeing of the country (UNDP, 2009; Zusammenarbeit, 2010). Adaptive capacity can be defined as the ability of a community to adjust its characteristics or behaviour, in order to expand its coping strategies under existing climate variability, or future climate conditions. It helps to reduce the magnitude of harmful outcomes resulting from climate-related hazards (Brooks and Adger, 2004).

It is also important to note that as well as climate change impacts, there are multiple rural stressors negatively affecting many rural areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as local environmental degradation, increasing population, land scarcity, food security issues, chronic poverty, poor governance etc., which intertwine with the effects of the changing climate to create challenges for economic development and undermining rural livelihood strategies. Various studies indicate that these combined stresses on rural populations in developing economies, disproportionately affect rural women (Dasgupta, et al., 2014).

This paper explores the hypothesis that women’s entrepreneurship development can improve adaptation responses. Entrepreneurship has been neglected in the rural climate adaptation literature to date. Various authors have worked on the relationship between women’s entrepreneurship, gender equality and rural development (Sarfaraz, et al., 2014; OECD, 2012; Allen, et al., 2007), but few have focused on the inter-relationship between entrepreneurship development, rural women’s livelihood practices and climate change (OECD, 2008; Mutekwa, 2009). The need to build rural adaptive capacity, and particularly to empower rural women is well documented, but there is a potential opportunity to explore how the promotion of an entrepreneurship culture could strengthen women’s adaptive capacity in the light of a changing climate. Africa faces special conditions and challenges such as rural infrastructural deficiency and corruption which affect entrepreneurial potential but there are also opportunities for climate entrepreneurship and investment (Innovation Systems and Clusters Program-Uganda 2011).

This study therefore raises the following questions: a) What are current climate change adaptation strategies in the rural areas? b) Are there climate change challenges for women’s livelihood practices? And, c) Are there opportunities associated with climate change challenges for enhancing entrepreneurship development in the study areas? To answer these research questions, the study sought to: a) Examine the impacts of climate change in the study areas; b) to assess current adaptation strategies in the study areas; c) Assess the challenges and opportunities of rural women in entrepreneurship development in the study areas; and d) Suggest a policy framework to enhance Nigeria’s rural women participation in climate entrepreneurship and other climate risk management practices.

Entrepreneurship and rural women

Entrepreneurship is a complex phenomenon that spans a variety of contexts. Definitions in the literature are highly varied, reflecting this complexity, but in this study, we employ the following definition: Entrepreneurship can be defined as the process of using private initiative to transform a business concept into a new venture or to grow and diversify an existing venture or enterprise with high growth potential (Aderoba and Babajide, 2015). Entrepreneurs identify innovative approach to seize an opportunity, mobilize money and management skills, and take calculated risks to open markets for new products, processes and services (UNDP, 1999). While entrepreneurship can occur without external intervention, there are also approaches which seek to catalyse and stimulate learning, knowledge development and capacity strengthening to improve outcomes. Relevant concepts in this regard include, a) Entrepreneurship development (ED) refers to the process of enhancing entrepreneurial skills and knowledge through structured training and institution-building programmes (UNDP, 1999); b) Entrepreneurial learning is also helpful – it refers to a process of facilitating the development of knowledge which can enable the creation and management of new business and enterprise ventures (Politis, 2005).

Viewing entrepreneurship as a process, it can be instructive to unpack the role of individuals and their capabilities. An individuals’ perceptions of their own capabilities regarding entrepreneurship can vary significantly, as can their ability to take advantage of opportunities as they arise for starting a business. In general, the higher the capability in the general population (i.e., people in a community believe they have the skills and knowledge to turn today’s problems to business opportunities), the higher the level of early-stage entrepreneurial activity and potential contribution to solving a community’s problem.

According to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2007), women are key to the development of entrepreneurship in any given society. They also help to eliminate some societal problems through their entrepreneurial activities in informal sectors, for example, adapting agricultural practices such as switching to crops and varieties that are flood or drought resistant, changing cultivation to more easily marketable crop varieties or to other animals (e.g. in Nepal: rearing goats and poultry farming; and in Bangladesh, rearing ducks instead of poultry) (WEDO, 2008). Therefore, a better understanding of rural women’s perceptions, attitudes, awareness and behaviour with respect to starting and managing climate-related enterprise initiatives and businesses could potentially help to guide future capacity strengthening efforts, expanding the base of women (entrepreneurs) and hastening the pace at which new ventures are created and climate change opportunities captured or barriers overcome. Formal or informal learning processes may be appropriate to achieve desired development, such as acceleration of employment generation and economic development. Entrepreneurship development focuses on the individual who wishes to start or expand a business and concentrates on growth potential and innovation. However, many women do not necessarily see themselves as entrepreneurs and have the confidence and capacity to identify potential climate change opportunities. To become entrepreneurs, women need to participate in entrepreneurial activities, taking risks, combining resources together in a unique way to take advantage of the opportunity identified in the immediate environment through the production of goods and services. Increasing women’s entrepreneurship can give women greater economic power, reducing poverty and enhancing their societal status.

Climate change and rural lifestyle

Climate change produces new and different weather patterns and extreme weather events; and research findings support the view that women’s economic insecurity increases more than men’s in the aftermath of natural disasters (Enarson, 2000). Women also recover more slowly than men from economic losses due to damage to property and the loss of livelihood (Athen, 2009). Food, water, health and energy are also particularly affected by climate change. These areas happen to be the basis of women’s livelihoods and fall within the purview of women’s socio-economic responsibilities (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2007). This experience makes their tasks become more gruelling and time consuming with the increased occurrence of floods and droughts associated with climate change.

Moreover, women’s lack of property rights and control over natural resources aggravated by their limited access to information, education, credit and technologies now translate to fewer means to deal with climate change. For instance, adaptation measures, related to curbing desertification, are labour-intensive and women often face increasing expectations to contribute unpaid household and community labour to soil and water conservation efforts. Women often rely on a range of crop varieties (agro-biodiversity) to accommodate climatic variability, but permanent temperature change would reduce agro-biodiversity and traditional practices (Aguilar, 2004).

Despite these challenges which result from gender inequalities in rural societies, there are also opportunities to build upon women’s existing roles and responsibilities to achieve climate adaptation goals, and where necessary to challenge cultural norms (e.g. to encourage self-confidence in their entrepreneurial capabilities).

Women in rural areas in developing countries play significant roles in the production of basic foods and natural resource management and should therefore be centrally involved in adaptation planning and implementation. For example, women can take action to conserve soil and water, if the environment is conducive and where they have the necessary resources to do so. An understanding of how women are affected by climate change and their capacity to contribute to climate adaptation strategies is essential for their effective involvement in climate change responses and for harnessing their capacity for appropriate mitigative and adaptive actions (Women’s Environment & Development Organization, 2007). Studies have shown various examples in different countries where women’s knowledge and actions have helped to control erosion, prevent flood damage, and improve access to water (Ajani, Onwubuya, & Mgbenka, 2013; Wuyep, Dung, Buhari, Madaki, & Bitrus, 2014). Women should therefore be an important part of decision-making processes regarding land and resource management in order to allow their knowledge to benefit entire communities.

Women have key roles in community natural resources management, innovation, farming and care-giving, thereby positioning them well to develop strategies for adapting to the changing environment. Experience has shown that communities fare better during natural disasters when women play a leadership role in early warning systems and reconstruction. Women tend to share information related to community wellbeing, choose less polluting energy sources, and adapt more easily to environmental changes when their family’s survival is at stake (Women’s Environment & Development Organization, 2007).

According to the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (2007), women and men are adapting their agricultural practices to naturally-varying climate conditions based on their specific needs, knowledge and access to resources. This same study found that when gender differentiated knowledge is properly understood and addressed, interventions to strengthen livelihoods and food security are more effective and efficient.

According to Denton (2002), one key climate-related opportunity (focused on climate mitigation) is the promotion of renewable energies that helps avoid or reduce greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, in rural areas of many developing countries there is a lack of energy services, which disproportionately affects women in their daily chores at home, since they are usually responsible for ensuring that energy is available at home for heating and cooking. In many parts of developing countries, women spend many hours daily gathering firewood and other energy sources. Thus, while rural energy initiatives could contribute to mitigation efforts, they could also be part of adaptation strategies: Energy production may also be a starting point for income-generation (Mitchell, Tanner, & Lussier, 2007). In Bangladesh, the Grameen Shakti (GS) microloans initiative combines renewable energy, jobs and skills training which helped to install more than 100,000 solar home systems in rural communities, creating employment opportunities while also empowering women and local youth (IPCC, 2007).

Theoretical framework

This study is based upon Human Ecology theory, as it dwells on the relationship between the environment and human activities and how the activities impact the environment. According to Marten (2001) human ecology is about relationships between people and their environment. In human ecology the environment is perceived as an ecosystem (Fig. 1). An ecosystem comprises of every element in a specified area - the air, soil, water, living organisms, economic and physical structures, including everything built by humans.

Human Ecology Model. Source: Marten (2001)

Humans are part of the ecosystem, better understanding the relationship between human social systems and the rest of the ecosystem, as depicted in Fig. 1, can be instructive. The social system comprises of the human population, and the knowledge, values, technologies and social organization that shape the behaviour of individual people in the society. The social system is a central concept in human ecology because human activities that impact on ecosystems are strongly influenced by the society in which people live. Values and knowledge - which together form our worldview as individuals and, collectively, informal society’s culture - shape the way that we process and interpret information and translate it into action. Social organization, and the social institutions that specify socially acceptable behaviour, shape the possibilities of what we actually do (actions), as individuals exert their agency. Like ecosystems, social systems can be on any scale - from a family to the entire human population of the planet.

The ecosystem provides services to the social system by making available materials, energy and information to the social system to meet people’s needs. Such services include water, fuel, food, materials for clothing, construction materials and recreation. Movements of materials are obvious; energy and information are less so. Every material object contains energy, mostly conspicuous in foods and fuels, and every object contains information in the way it is structured or organized.

Material, energy and information move from social system to ecosystem, as a consequence of human activities, which impact the ecosystem. Some of these activities are entrepreneurial in nature. As a result, people affect ecosystems when they use resources such as water, fish, timber and livestock grazing land. For instance, in this study, such resources have been turned into entrepreneurial activities such as: fish farming and processing, livestock farming, non-timber products (snail and herb picking). After using materials from ecosystems, people return the materials to ecosystems as waste which often contributing to environmental degradation, as well as instances of unsustainable exploitation of the resources in the first place. People intentionally modify or reorganize existing ecosystems, or create new ones, to better serve their needs (Marten, 2001).

With machines or human labour, people use energy to modify or create ecosystems by moving materials within them or between them. They transfer information from social system to ecosystem whenever they modify, reorganize, or create an ecosystem. The crop that a farmer plants, the spacing of plants in the field, alteration of the field’s biological community by weeding, and modification of soil chemistry with fertilizer applications are not only material transfers but also information transfers as the farmer restructures the organization of his farm ecosystem (Marten, 2001).

According to Terry (2009), the problem of deforestation is an example of human activities that generate a chain of effects back and forth through the ecosystem and social system. For centuries, people have depended on forests for domestic energy supply, especially, in rural areas. This was not a problem as the population was small. However, the situation has changed with populations growth particularly in land constrained areas. Forests, especially in Nigeria, have virtually disappeared, because of unabated demand for wood, weak protection mechanisms and viable energy and income generating alternatives. Fuelwood in now in such short supply that people resort to cooking in many localities with cow dung or even broken plastics, with deleterious health, livelihood and the ecosystem impacts (Terry, 2009). Using cow dung as fuel also reduces the quantities available for use as manure on farm fields, affecting food production. In addition, in some communities, the flow of water from the hills to irrigate farm fields during the dry season is less than previously, as the hills are no longer forested. Furthermore, the quality of the water becomes poor as the deforested hills are severely eroded and the adjoining low land heavily silted with large sediments from higher altitudes. This decline in the quantity and quality of water available for agriculture reduces food production even further. The result is poor nutrition, low income generation and poor health for people, especially, the children and women (See Fig. 2).

Figure 2 shows how the impact of human activities on the environment can be conceptualized. Such impacts can be fairly invisible so that people do not notice until they accumulate and produce serious challenges. Problems may appear suddenly, and sometimes at a considerable time interval from the human actions that cause them. Devastating floods and crop destruction have now become regular events in most communities. Urbanisation processes pose challenges for rural areas, because of outmigration levels for example, affecting agricultural production and other livelihood practices. Most obviously, human interactions with the environment have induced global warming creating climate change impacts, such as growing unpredictability in rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events which have had various effects on the inhabitants, most especially, the most vulnerable. Globally, such effects contribute to food insecurity, water scarcity, droughts, induced alterations of agricultural activities and other livelihood practices, flooding, rise in sea level and so on.

The theory advocates for ecologically sustainable development, i.e. humans should interact with ecosystems in ways that allow the latter to maintain sufficient functional integrity to continue providing humans and all other creatures in the ecosystem with the food, water, shelter and other resources that they need (Marten, 2001). The present generation must respond to their needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Damaged ecosystems that lose their capacity to meet basic human needs close off opportunities for economic development and social justice for its inhabitants. A healthy society gives equal attention to ecological sustainability, economic development and social justice because they are all mutually reinforcing.

Methodology

A mixed method approach underpins the study. The research both qualitative and quantitative data collection to answer the research questions. The empirical research aims to elicit the perspectives and experiences of rural women in selected states of Southwest Nigeria. Four different vegetation zones were selected and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), a qualitative method, were held with women from the various communities. A questionnaire survey (a quantitative method) was administered to a sample of rural women. The decision to focus on rural women in different vegetation belts was due to the hypothesis that the impact of climate change will be different for women in different vegetation zones and engaging in diverse livelihood practices. The livelihood practices considered in this study are farming, food processing, non-timber forest products and non-farming activities. The findings from both the qualitative and quantitative methods were analysed and combined to answer the research questions, highlighting the experiences of rural women and to identify climate-related entrepreneurship opportunities, applying the findings by formulating policy recommendations, encouraging policy makers to design appropriate interventions for rural communities.

The study is limited in its scope since comparisons cannot be made with other regions of Nigeria.

The study area

Nigeria lies roughly between latitudes 4o and 14oN and longitudes 3o and 15°E covering a land mass of approximately 923,768 km2which is about 14% of the land area of West Africa (Federal Ministry of Environment, 2009). The country is bordered by Benin Republic to the West, the Niger Republic to the north, the sub-equatorial Cameroun to the east and the Atlantic Ocean to the south (Iloeje, 1981). In 2006, the country’s population stood at about 170 million (NPC, 2006) with 36 States grouped into six geopolitical zones for political and development purposes and 774 local government areas (LGAs).

This study was conducted in the Southwest region of Nigeria comprising of Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun and Oyo States. It lies in the region of 60 and 80N latitude and 40 and 6°E longitude. The states have a total population of 27,722,432 across different vegetation zones (NPC, 2006). Ondo state possesses three different types of vegetation zones, namely, rainforest, fresh water swamp and mangrove. Oyo state has two which are rainforest and guinea savanna. Ogun state has similar to that of Oyo state, but with the inclusion of fresh water swamp zones. Ekiti state shares the same vegetation zones with Oyo state, but it has more rainforest than Oyo state. Lagos state is mainly under fresh water swamp and there is very little rainforest. Lastly, Osun state has two vegetation zones - the rainforest and savanna.

Originally, the region was rich in forest resources, much of which is now lost. Agricultural activities and other livelihood practices form the basis of entrepreneurial activities for rural dwellers. Women in this region make up about 49% of the total population with a population of 13,641,275 and they are known to be involved in various livelihood practices, though, mostly, on a micro and small scale in the rural areas (NPC, 2006).

Sampling techniques

The multi-stage sampling technique was used to sample women for the questionnaire survey. This involved sampling women who were involved in different types of identified livelihood practices. Three states (Oyo, Ondo and Ogun) from the Southwest region of the country were purposively selected, due to the presence of at least two types of vegetation zones in each. Although, Ekiti State met the selection criteria, there was political turbulence in the state as at the time of field work and so it was excluded. Lagos State, which also possesses more than one vegetation zone, is predominantly urban and so it was not selected. From each selected state, two Local Government Areas (LGAs) representing the different vegetation zones were purposively selected and one community from each LGA and vegetation zone was chosen based on information obtained from the Ministry of Forestry of each State.

The National Planning Commission (2009) zoned Oyo State into Oyo Central, Oyo North and Oyo South. Hence, one LGA was chosen from Oyo South (Ido LGA) and Oyo North (Iseyin LGA) to represent each of the two main vegetation zones in the state (the rainforest and guinea savanna respectively). The communities selected in the LGAs are Aba Serafu in Iseyin LGA and Araromi Idowu in Ido LGA. In Ogun State, two LGAs are at the two extreme ends of the State and have both forest and savanna vegetation types. The chosen communities are Oke Ola (Woodland Savanna) in Imeko Afon LGA and J4 (Rain forest) in Ijebu East LGA. Out of all the southwest states, only Ondo State has both mangrove and fresh water swamp vegetation zones. Ajagba community in Ode Irele LGA and Igbekebo in Ese Odo LGA which had fresh water swamp and mangrove vegetation, respectively, were selected for the study.

Sample size

Each household in the communities had at least a woman involved in one of the business classifications (food processing, non-timber forest products and non-farming activities). Since the communities are small in size, each house was visited for the questionnaire administration. Each household in the communities was therefore represented. For the quantitative data, the questionnaire was distributed randomly on household bases among women involved in various livelihood practices to capture quantitative data. Five hundred and ninety-five (595) questionnaires were administered and all were retrieved. This was made possible because 10 field workers were employed, trained and personally administered the questionnaire to respondents over a period of 3 months. Field workers and researcher moved from community to community.

Women who participated in the FGDs were chosen randomly by community women leaders. They were asked to identify women in the community so that the range of different livelihood strategies which had been identified would be covered. Four (4) FGDs were organized in each community based on the four livelihood classifications for this study. Each FGD comprised of 8–10 rural women who were not part of the quantitative phase. The overall FDG sample size was 240 women.

Measurement of variables

Based on human ecology theory, this study sought to examine the perceptions of respondents on the relationship between climate change and livelihood practices. Climate parameters included rainfall patterns, temperature, humidity, drought and change in sea levels. These climate parameters were measured on a 5-point likert scale (strongly agree was coded 5, agree coded 4, undecided coded 3, disagree coded 2 and strongly disagree coded 1). While the perceived impact of climate change on livelihood practices was measured on a 3-code item: High = 3, Moderate = 2 and Low = 1, and respondents were asked to tick these responses against some perceived impact statement as it affected their livelihood practices.

Data analysis

Data from the questionnaires were captured electronically and analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for descriptive analyses and analysis of variance was used to examine significant relationship among the mean ratings of some variables, while Duncan Multiple Range test was employed to separate the means. Atlas.ti was used for thematic analyse for the qualitative data. The results of the two sets of data were integrated to identify key patterns.

Results and discussion

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

An analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, differentiated by vegetation zones was undertaken to highlight similarities and or differences in the zones. The respondents were classified into six groups (Table 1). Respondents under 20 years of age were only found in rainforest and savanna zones. Across the vegetation zones, women were more concentrated in the age group ranges between 21 and 50 years old. Out of these, about 66% of the respondents were from rainforest, 77% from savanna, 63% from mangrove and 64% from fresh water swamp zones. The mean age of the respondents was 45 years. This implies that most of the women were in their productive years, hence, their involvement in more than one livelihood activities.

About 23.5% of the respondents were involved in other occupation for various reasons such as: the need to source for more income to diversify their enterprises and the need to augment income revenue for major activities.

A greater proportion (80%) of the respondents were married across all the zones. About 78% were married among respondents from rainforest zones, 88% from savanna zones, 71% from mangrove zones and 81% from fresh water swamp zones. The percentage of widowed women was highest in the mangrove areas with 27%, followed by 17% from fresh water swamp, 16% from rainforest and 6% from Savanna. The high levels of married status and widowed women as a proportion of the female populations in these vegetation zones coincides with their involvement in more than one occupation. Married women tend to have greater household responsibilities to cater for, and so may need to supplement their income from farming and forestry activities. Oberhauser and Pratt (2004) noted that married women are often socially-ascribed responsibility for providing for the household needs of their families and prevailing gender norms thus push them to engage in diverse livelihood strategies.

The analysis of the educational level of women respondents revealed that about 59% of the women in rainforest zones had formal education. In savanna areas, almost half had formal education and 67% in mangrove areas. While 58% were exposed to formal education in the fresh water swamp areas. The study recorded an appreciable percentage of respondents from each vegetation zone with no formal education. Only 2.0% of all the respondents had undertaken tertiary education, where advanced skills had been acquired. This explains why most of the women in the study areas were mostly confined to unskilled activities. As per Ranjan (2006) low levels of education and skills restrict women’s participation in non-farm activities and vice versa.

In this study, it was observed that involvement of respondents in the following activities such as farming, food processing and non-farming activities, cut across the different vegetation belts. About 37.0% of the respondents were involved in farming, 27.9% were active in non-farming activities, 31.1% in food processing and approximately 4.0% in non-timber forest products. Across the vegetation zones, the highest percentage of women involved in farming was found in the rainforest zones (46%), followed by 39% in the fresh water swamp zone. Across the vegetation zones in all the study areas, it was observed that the respondents from the savanna zone were more involved in food processing, than other vegetation zones.

It was observed that the percentage of women involved in non-timber forest product exploitation is reducing. This could be as a result of climate and environment-related changes in the study areas, such as loss of forests.. For instance, women interviewed reported that some of the herbal leaves they used to find from the forest are now extinct, they believe it is as a result of excessive heat.

More than half (59.0%) of the women interviewed had over 10 years of work experience. More than a quarter of the respondents in each of the vegetation zones had more than 20 years of work experience and about a quarter from each vegetation zone had become involved in various activities in the last 5 years. Other studies (See Ajani and Igbokwe, 2013; Mwangi, 2015) find that years of experience in livelihood practices encourage and enhance diversification, thereby increasing entrepreneurship involvement.

Though it was observed that nearly all of the women had no formal book keeping system for their business transactions, they were able to report on their monthly generated income (Akinbami, 2015). Despite the well-known challenges in gathering estimates of monthly income for rural farmers through questionnaire survey methods, the findings indicate some clear patterns which appear consistent with other studies. According to the women interviewed, a greater percentage of income generated monthly, concentrated around ₦10,000 and ₦20,000, that is, average monthly income. About 10.6% of the total respondents earned less than ₦5000 average monthly income, while 17% earned between ₦5000- ₦10,000 and less than one tenth of the respondents earned above ₦20,000 monthly. The mean average monthly income was about ₦7500. From this data, it is obvious that the majority (about 70%) of the rural women earned less than the approved minimum wage of ₦18,000 in the formal sector in the country. This again could be the reason why most of the women’s livelihood practices remain at the micro level, since there is a lack of sufficient capital for expansion. In situations of chronic poverty, particularly among the women, there are likely to be major barriers to entrepreneurship.

Assessment of perceived impacts of climate change on livelihood practices in the study areas

To assess the perceived impacts of climate change on the livelihood practices of women in rural areas, a first step is assessing their awareness of the changing climate.

As a follow up to a study by Akinbami, et al. (2015), the awareness level of the respondents concerning change in climate parameters was also found to be moderately high, irrespective of the livelihood involved, across different vegetation zones in the study areas. This finding contradicts the notion by some authors Adetayo and Owolade (2012) and Egbe, et al. (2014) that awareness of climatic changes is low among rural dwellers.

From all the vegetation belts (98.5%) a majority reported that the rainfall pattern has changed from what it was before, there is now less rainfall to give a good farm yield at the appropriate time, while only a few (1.5%) of the respondents were unable to give their opinion on the rainfall pattern.

More than a quarter (25.7%) reported that more drought is experienced and 81.2% were aware of increased flooding. The awareness level of the respondents about an increase in temperature is also high (98.5%). More than nine-tenths (90.3%) were aware of the change in humidity in their environments. Awareness of sea level rise was low in rainforest and savanna zones for obvious reasons. Figures 3a-e reveal the level of awareness on different climate-related parameters across the four vegetation belts.

a Level of awareness of change in rainfall patterns across vegetation zones. b Level of awareness of change in temperature patterns across vegetation zones. c Level of awareness of change in humidity patterns across vegetation zones. d Level of awareness of severity of drought across vegetation zones. e Level of awareness of change in sea level patterns across vegetation zones

Awareness is highest amongst rural women inhabitants with respect to changes in rainfall and temperature. As 94% of women depend on rainfall for their livelihood activities the impacts are likely to be important. The next section explores perceived impacts of climate change on women’s livelihood activities.

Perceived impacts of climate change on women’s livelihood activities

The research reveals women’s perspectives on how climatic-changes are affecting their livelihoods across the different vegetation zones. It ranges from delayed rainfall, strong wind, and heavy rain leading to flooding thereby affecting the roads to over flown rivers (Fig. 4).

All the women were able to comment on the effects of different aspects of the climate and changes in climatic factors as it affects their livelihoods. On rainfall patterns, it was reported that there has been delayed occurrence of rainfall and when it occurs, the intensity was unusually heavy and had an adverse effect on their farm products. This was also reported by women during the Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) in various vegetation belts. Figure 5 reveals the effects of climate change as reported by the women on the various livelihood practices across vegetation belts.

Figure 6 shows the comments from women who are engaged in the exploitation of Non-Timber forest products. In all the vegetation zones visited, it was observed that this livelihood practice is reducing in importance in rural livelihoods. Most of the women involved are diversifying into farming activities instead due to the loss of forest resources. This has great implications for the poverty levels of women and rural households.

At the study areas, women involved in farming activities reported various ways perceived changes in the climate have affected their livelihood practices. The effects are presented in Fig. 7 below.

The reported negative impacts of changes in climate variability has direct implications for rural household food security. According to Slater, et al. (2007) by 2080 around 1300 million people may be at risk of hunger. This therefore calls for more investment in sustainable agricultural intensification, requiring the involvement of women, as well as men, given their important role in agricultural production in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Challenges

The reported climate-related changes across the vegetation zones and their negative impacts on women’s and rural household livelihood strategies, has contributed to and exacerbated the challenges women already face in engaging in entrepreneurship development, learning and innovation.

During the qualitative sessions, the women gave their reasons for which constrain their engagement in the development of micro and small business operations in rural areas. Figure 8 shows some of the challenges raised during the FGDs across the vegetation zones.

These challenges which affect enterprise development, likely also contribute to suppressing income levels or income growth. Based on the women’s account, the income pattern for each vegetation zone over the last 25 years is shown in Figs. 9a – d. Overall, the broad income trends reported, suggest differences between the vegetation zones, which could, in part, potentially relate to the varying onset and nature of climate-related impacts on livelihoods between the zones Fig. 9a revealed that the income pattern of the women in rainforest vegetation zone fluctuates over the last 25 years. Most of the women reported that their income level has not been constant, but has declined, especially in the last 15 years. Though the graph indicates that more women reported a slight increase in their income level, but this negates reports from the women during FGDs where the women lamented lack of adequate fund for their business operations.

a Income pattern of respondents in the rainforest vegetation zone over the last 25 years. b Income pattern of respondents in the savanna vegetation zone over the last 25 years. c Income pattern of respondents in mangrove over the last 25 years. d Income pattern of respondents in fresh water swamp over the last 25 years

Figure 9b revealed a different income pattern in the savanna zone compared with the rainforest vegetation zone. The income pattern in savanna was more constant than rainforest area, until the last 10 years. However, the women have been experiencing a steady reduction in their income level over the last 25 years. This suggests that women in savanna had experienced a negative income trend, which could be partly the result of the effects of climate change having an impact upon them sooner than in the rainforest areas, although other factors such as localized environmental degradation could also be a factor. However, it was also observed that the women experienced great income increase in the last 5 years.

The income pattern of respondents from the mangrove vegetation zone as observed to be constant between 25 and 20 years ago, but the women reported an observed drastic drop in their income was noticed 15 years ago due to heavy flooding experienced during that period which affected their fish business.

The income pattern of fresh water swamp respondents is almost similar to that of the mangrove vegetation zone inhabitants. The women reported a constant pattern in livelihood income between 25 and 20 years ago. According to the reports from FGD, the women reported only recent experiences in climate-related trends affecting their livelihoods. Around 15 years ago they reported difficult conditions with respect to their livelihood practices, with an attendant decline in their income level.

Table 2 above shows the mean rating of some variables indicating the perceived effect of climate change on the livelihood of the rural women. This becomes important as it will help to further examine the impact of climate change, the perception of the women which will determine success of any established adaptation strategy. Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree (That is, strongly agree was coded 5, agree coded 4, undecided coded 3, disagree coded 2 and strongly disagree coded 1). Analysis of variance was used to examine significant relationships among the mean ratings of some variables, while Duncan Multiple Range test was employed to separate the means.

The analysis reveals that most of the women involved in crop farming in all the vegetation zones do strongly agree (with mean of approximately 5 in most related questions) that climate-related changes have greatly affected soil fertility, caused unpredictable weather, and a prolonged dry season.

The result also suggests that there is deforestation occurring in the rural areas, which likely intertwines with the impacts of climate change in the study areas, reinforcing the point that there are multiple factors shaping rural women’s incomes and livelihoods, not only climate change-related ones.

Climate-related entrepreneurship opportunities for rural women

Women’s Environment & Development Organization or WEDO (2007) reported that women are more than 50% of world population and can play important roles in climate change mitigation: not only do they manage most of the households, childcare and education, they are also often ready to take action to help mitigate climate change as a means of risk aversion, if educated on the opportunities options available. The report (WEDO, 2007) further states that women have developed specific adaptive strategies to cope with climate change-induced problems in livelihood, health, shelter and energy sectors, etc. in some countries.

The research clearly shows that there are major climate-related impacts affecting rural women and households in the study areas. Awareness of these climate-related changes and how they are affecting livelihoods is high amongst the women interviewed. Income data suggests that in many cases incomes are declining or fluctuating, with issues of chronic poverty reported. Many of the adaptation strategies being utilized by rural women appear to be essentially coping strategies, rather than adaptation strategies which can build up livelihood assets and thereby increase resilience. Further, the challenges which prevent enterprise development are significant, including lack of access to finance and skills.

One of the ways that additional support could be provided to enhance adaptation programming is to focus more clearly on entrepreneurship, as currently there are significant challenges for women to develop micro and small-scale enterprises.

Many women do not observe opportunities for entrepreneurship focusing on the (very real) challenges that they face to secure their livelihoods, which are only exacerbated by climatic changes (Fig. 10). Yet the discussions with women do reveal some potential climate-related opportunities. For example, in Araromi Idowu community where practically all houses produce fufu (staple food produced from processed cassava), all households rely upon what is described by one female interviewee as ‘colored and smelly’ water from the single deep and many shallow dug wells. The inserted picture shows how water is gotten from the swallow wells. Currently, women in the village all obtain alum from markets in Ibadan, which is some kilometres away from the community and means all the women having to make individual trips to obtain the same product. A business opportunity exists for the manufacturing and sale of alum (Aluminium Sulfate) in the village to purify the water before use. More research would be needed to establish the business case and potential risks of such a livelihood activity and whether it would indeed be suitable or accessible for rural women, and whether a wider set of rural women would benefit. This would likely require additional support via rural business incubation services. Most houses in Southwest Nigeria have Moringa Olifera planted around them. The stem of the plant can be used to coagulate and purify water for use. Another potential business opportunity for women in rural areas where there is water logging problem is developing nurseries for various kinds of trees (called apakuro in local dialect such as Tristaniopsis laurina) that are used to modify damp or wet environments for sale. These trees have the capacity to control waterlogging by absorbing excess soil water. As with any new technology or proposed livelihood activity, it is essential that these are developed through participatory processes with local women and rural households, to ensure that there is good understanding of the challenges which need to be addressed and so appropriate support can be given for the incubation of new business ideas as they emerge from the village level or are co-identified with external partners.

Theoretical contribution and future research direction

This study makes several contributions to the literature. Specifically, it contributes to research on the interrelationship between women entrepreneurship, rural development and climate change. It provides information on how human interactions with the ecosystems can be managed to produce a healthy environment, that is well balanced, thereby taking care of the issue of food and water security. This will in turn increase the livelihood practices of the rural dwellers, especially, the women, who are part of the vulnerable to climate change effects such as rise in temperature, unpredicted rainfall, flooding.

Besides this, it helps to advance knowledge on the possibility of turning the effects of climate change into entrepreneurship opportunities. It has also revealed that the climate change consequences are not likely to reduce hence adaptive measures that are suitable for the various vegetation zones should be put in place in order for the rural women to cope with the impacts of climate change. These adaptive strategies are additionally potential entrepreneurship options that will eventually enhance livelihood practices, thereby reducing poverty level among the rural women.

However, for effective implementation and realization of the suggested adaptive strategies, development projects that serve the dual purposes of adaptive measures and entrepreneurship opportunities appropriate for each vegetation zone need to be established and effectively monitored. The outcomes of these can serve as templates to be adopted in communities with similar vegetation zones and development parameters.

This study did not cover vegetation zones in other regions of Nigeria for comparative study, hence, similar studies need to be carried out in such regions.

Recommendation

The empirical findings indicate significant challenges facing rural women and hindering their engagement in enterprise development – challenges which already existed, but which may be being exacerbated by climatic changes. At the same time climate change mitigation and adaptation imperatives have led to a wide range of new climate smart technologies, infrastructure developments and institutional innovations which could be supported in rural areas and which could catalyse rural women to engage more in ‘climate entrepreneurship’ - given adequate investment and support. Some of the strategies would indirectly facilitate more entrepreneurship by increasing the livelihood assets of a household (rainwater harvesting in households), or of an entire community (e.g. improved, small scale irrigation schemes), i.e. stimulating more entrepreneurial activities by making water supply more secure. Others could directly catalyse more entrepreneurship amongst project participants (e.g. support for biogas projects) or specific groups of women (e.g. collective purchase or marketing, group loan schemes). Few of these innovations are only climate-specific or necessarily new to development. However, new sources of climate and development aid finance are creating opportunities for the scaling of such opportunities as well as increasing the need for such interventions. Enhancing women’s entrepreneurship could be facilitated by channelling such funding to (climate-informed) business incubation services, i.e. advisory and training services in rural areas. Such incubation services need to have a good awareness of climate impacts and opportunities) and capacity to build up entrepreneurship in a participatory, adaptive manner.

Green economy strategies

Green economy strategies improve human well-being and social equity, while significantly reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities (UN, 2011). Experience elsewhere suggests that green economy strategies can be low carbon, resource efficient and can also support job creation and poverty reduction. For example, waste from cassava processing, can be converted into biogas to improve rural living standards rather than being left in the open and allow to generate CH4 (Mathene) which can be injurious to the environment and health (Akinbami & Momodu, 2013). Slurry/sludge which is a by-product of biogas production can be used as manure to further enhance agricultural yields. South Africa is one of the countries that has adopted green economy policies, seeing them as a path to sustainable development, because of the potential for achieving inclusive economic growth, social protection and protecting natural ecosystems (Kaggwa, et al., 2013). However, policy implementation in rural areas would require significant investment and support to integrate such technologies into current production processes and along value chains to the customers.

Irrigation and lined canals

The study findings demonstrate that water supply is one of the major challenges in most of the communities in the various vegetation zones studied, including for rural women. The development of irrigation schemes is one pathway which can address water supply issues, when rains are delayed increasing the stability of supply. Lining canals can ensure that the water stored will be retained and not escape into the ground water, which can then be used in periods of delayed or scarcity of rainfall for irrigation and other domestic purposes. Irrigation schemes and lined canals have been created in countries like Sri Lanka and Portugal. In Sri Lanka, it has contributed to the availability of water not only for agriculture but also for domestic use by rural households (Meijer, et al. 2006). Investment in climate-proofed infrastructure can strengthen the adaptive capacities of rural communities, overcoming one of the likely barriers to increased entrepreneurship.

Harvesting of rainwater

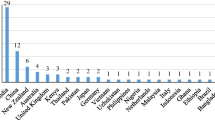

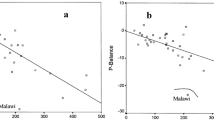

Another means of improving water supply chain, is improving rainwater harvesting to capture and stores rainwater for later use, thereby reducing demand on existing limited water supply, and also potentially reducing run-off and erosion. This practice has been widely adopted and used in some countries such as Japan, USA, China, Germany, Singapore, Thailand. This practice is also becoming more widespread in African countries such as Botswana, Togo, Mail, Malawi, South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania have embarked on different projects with rain water harvested (UNDP, 2010). Small-scale rainwater harvesting can enable households to improve the security of their water supply, and potentially stimulating more entrepreneurial activity.

Entrepreneurial Spirit and collective action

There is significant potential for collective action by women to improve livelihoods (Baden, 2013). Over-dependence on governmental intervention appears to be an issue emerging from the field research in South Western Nigeria. Promoting collective action may require support from external actors, given the challenges faced by rural women, particularly in remoter rural areas far from markets, but this does not mean ‘waiting for government to act’. There may also be activities which can be undertaken within communities, building upon indigenous climate adaptation measures. Individual ‘champions’ can play a role in initiating such movements in communities and researchers can identify ‘positive deviance’ by innovators, supporting peer learning at the community level so that all can benefit (Duncan, 2017).

Climate smart agriculture

Climate-smart agriculture is an approach defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) that ‘helps to guide actions needed to transform and reorient agricultural systems to effectively support development and ensure food security in a changing climate’ and it has three key goals: ‘sustainably increasing agricultural productivity and incomes; adapting and building resilience to climate change; and reducing and /or removing greenhouse gas emissions where possible’. Stakeholders at all level identify agricultural strategies which are locally tailored and appropriate to their local conditions. A whole range of production and resource innovations and enabling frameworks are identified.

It has been noted by Asare, et al., (2016) that some countries like Ghana, Nigeria, Liberia, Côte D’Ivoire farmers have poor access to improved planting materials and seedlings which serves as a major contributing factor to production inefficiencies. What is important is improving farmers’ access to good quality seed – whether through public or private systems in the development of national seed supply chains. Improving agricultural advisory and extension services is critical in improving farmers’ access to climate smart agricultural knowledge and support and this includes training and support for women’s access to quality seed and appropriate climate information to improve yields.

Producer organisation, incubation support and revolving loan

Small-scale producer organisation is often key to achieving sustainable participation in beneficial value chains. Incubation support services in rural areas are also a means of supporting business growth (Macqueen and Bolin, 2018) and should be made gender sensitive to promote women’s economic empowerment.

Soft loans can stimulate enterprise development activity and so should be made available to women in rural areas to stimulate business growth. Women can be encouraged to organise themselves into groups and have such loans revolve among them, helping to build up financial capital and boosting livelihood and entrepreneurial activities This method can serve as a control measure on each borrower to utilise the money well and payback the funds when due, since the other counterparts will be waiting for their turn to access the loan. These kinds of institutional innovations are as important as technological ones for achieving climate adaptation, but in some cases, there may be a need for the creation of alternative livelihood options where impacts are severe and what is key is systems which enable real time monitoring and learning to ensure appropriate adaptation strategies (Howden et al., 2007).

Conclusion

This study finds that women in South Western Nigeria have high levels of awareness of changes in their climate and identified multiple impacts on their livelihoods resulting from climate-related variability. They identified key resource-related challenges which constrain their ability to engage in entrepreneurial activities, linked to issues of poverty and risk, as well as a culture of dependence on government action. However, the research indicates several possible opportunities where women could engage in entrepreneurial activities, given appropriate support and facilitation. The study also found that women are experiencing declines in their incomes or volatility in their incomes – which also may undermine any notion of taking risks in entrepreneurial enterprises. We found that the women in the coastal zones (mangrove and fresh water swamp) may be experiencing climate-related impacts more recently than their counterparts in other zones. This chimes with work on climate-smart agriculture which encourages the development of locally tailored adaptation strategies, given the regional variations which can exist and the multiple factors which can influence livelihoods, including climate and environmental factors as well as markets. The results of the study reaffirm the dynamic inter-relationship between the environment (e.g. changing patterns of weather and climate, loss of forest resources etc) and human livelihood activities, which evolve in response as well as acting as a cause – in line with human ecology theory.

The increasing effects of climate impacts on the livelihoods of women and the wider community in this region clearly indicators the need for increased support to help these women overcome the challenges confronting and to take advantage of potential opportunities which may arise as a result of changing contexts, including new flows of development and climate finance, for example. The paper thereby enhances our understanding of potential entrepreneurship opportunities associated with a changing climate which in turn is creating additional pressures on local livelihoods and disproportionately affecting women. Too often discussions of women in rural development have treated them as being ‘passive actors’, and yet it is vitally important to recognize women’s agency, their capacity to engage in adaptation strategies and collective action, as well as understanding the specific gender-related challenges they face, including intersecting discriminations based on identity and wealth.

Adaptation strategies can build and improve the resilience of people living in communities most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, but it is critically important that such adaptation approaches should be gender-sensitive. The involvement of local authorities and community-based organisations in the development of such gender-sensitive adaptation strategies will be crucial, as well responses across scales (e.g. including governments and private sector actors).

There are a wide range of opportunities which can build adaptive capacity amongst rural women. These range from new technologies, infrastructural development and institutional innovations, all of which can, if successfully facilitated in a participatory approach, could build up women’s livelihood assets and household resilience, catalysing greater risk appetite and willingness to participate in entrepreneurial activities and ultimately contributing to a low carbon, more vibrant rural economy as a whole.

References

Aderoba, CT & Babajide, DA. (2015). Business Enterprises and Entrepreneurial Practices in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Management. Vol. 7(18) pp 7-16 ISSN 2222–1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222–2839 (Online)

Adesina, F. A., & Odekunle, T. O. (2011). Climate change and adaptation in Nigeria: Some background to Nigeria’s response – III. International conference on environmental and agriculture engineering IPCBEE Vol. 15. Singapore: IACSIT Press.

Adetayo, A. O., & Owolade, E. O. (2012). Climate change and mitigation awareness in small farmers of Oyo state in Nigeria. Open Science Repository Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.7392/Agriculture.70081902.

Aguilar, L. (2004). Fact sheet on: Climate change and disaster mitigation Costa Rica IUCN.

Ajani, E., Onwubuya, E., & Mgbenka, R. (2013). Approaches to economic empowerment of rural women for climate change mitigation and adaptation: Implications for policy. Journal of Agricultural Extension, 17(1), 23–34.

Ajani, E. N., & Igbokwe, E. M. (2013). Promoting entrepreneurship and diversification as a strategy for climate change adaptation among rural women in Anambra state. Nigeria. . Journal of Agricultural Extension, 16, 2.

Akinbami, C. A. O. (2015). Assessing the implications of book-keeping and payment culture on sustainable female entrepreneurship development in Osun state, Nigeria. Ife Social Science Review., 24(2), 71–95.

Akinbami, CAO, & Momodu, AS. (2013). Health and environmental implications of rural female entrepreneurship practices in Osun state Nigeria. AMBIO, A Journal of the Human Environment. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-012-0355-5.

Akinbami, C. A. O., Olawoye, J. O., & Adesina, F. A. (2015). Rural women belief system and attitude toward climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in Nigeria. Climate Change Adaptation, Resilience and Hazards. Springer.

Allen, E., Langovitz, N., & Minniti, M. (2007). Global entrepreneurship monitor 2006; report of women and entrepreneurship. Boston: The Center for Women's Leadership at Babson College and London Business School.

Asare, R, Afari-Sefa, V & Muilerman, S. (2016). Access to Improved Hybrid Seeds In Ghana: Implications For Establishment and Rehabilitation of Cocoa Farms. Expl Agric. page 1 of 13. Cambridge University Press 2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479716000247

Athen, P. (2009). Financing for climate change mitigation and adaptation in the Philippines: A pro-poor and gender-sensitive perspective. Reality Check, 1–14.

Baden, S. (2013). Women's collective action in African agricultural markets: the limits of current development practice for rural women's empowerment. Gender & Development, 21:2, 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.802882

Brooks, N. and Adger, W.N. (2004) Technical paper 7: Assessing and enhancing adaptive capacity, pp.165–182. http://www4.unfccc.int/nap/Country%20Documents/General/apf%20technical%20paper07.pdf

Dasgupta, P., Morton, J.F., Dodman, D., Karapinar, B. , Meza, F., Rivera-Ferre, M.G., Toure Sarr, A. & Vincent, K.E. (2014). Rural areas. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 613–657.

Davies, M, Oswald, K, & Mitchell, T. (2009). Climate Change Adaptation, Disaster Risk Reduction and Social Protection In OECD (Ed.), Promoting Pro-Poor Growth: Social Protection.

Denton, F. (2002). Climate change vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation: Why does gender matter? Gender and Development, 10(2), 10–20.

Duncan, G. (2017). ‘How change happens’. 2017 Oxfam. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/womens-collective-action-unlocking-the-potential-of-agricultural-markets-276159.

Egbe, C. A., Yaro, M. A., Okon, A. E., & Bisong, F. E. (2014). Rural peoples’ perception to climate variability/change in Cross River state- Nigeria. Sustainable Development, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n2p25.

Enarson, E. (2000). Gender and Natural Disasters. IPCRR Working Paper (Vol. 1). Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Federal Ministry of Environment (2009). Nigeria and Climate Change: Road to COP 15. Abuja, Nigeria.

Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. (2007). Women and food security. Geneva: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2007). 2006 Report on Women and Entrepreneurship. Centre for Women Leadership.: Babson.

Hall, G., & Patrinos, H. A. E. (2006). Indigenous people, poverty, and human development in Latin America: 1994–2004. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Howden S. M., Soussana, J-F., Tubiello, F.N., Chhetri, N., Dunlop, M., and Meinke, H. (2007). Adapting agriculture to climate change. PNAS December 11, 2007. 104 (50) 19691–19696; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701890104

IFAD 2001. Rural Poverty Report 2001: The Challenge of Ending Rural Poverty. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Iloeje, NP. (1981). A New Geography of Nigeria. Great Britain.: Longman, .

Innovation Systems and Clusters Program-Uganda 2011. Climate Change Innovations and Entrepreneurship. Research Report Submitted to Worldwide Fund for Nature Uganda Country Office. http://www.climatesolver.org/sites/default/files/reports/110601.pdf. Accessed on 18 Sept 2017.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. (2007). Gender Aspects of Climate Change, Briefing paper, .

IPCC. (2007). Climate Change 2007: Mitigation of climate change, . Bangkok.

IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2017: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge UK.

Kaggwa, M, Mutanga, SS, Nhamo, G, & Simelane, T. (2013). South Africa’s Green Economy Transition: Implications for Reorienting the Economy Towards a Low-Carbon Growth Trajectory. Occasional Paper No 168.Economic Diplomacy Programme.

Kronik, J., & Verner, D. (2010). Indigenous peoples and climate change in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington: World Bank.

Macqueen, D., & Bolin, A. (2018.) Forest business incubation: Towards sustainable forest and farm producer organisation (FFPO) businesses that ensure climate resilient landscapes. ISBN 978-92-5-130394-8.

Marten, GG. (2001). Human Ecology - Basic Concepts for Sustainable Development. : Earthscan publications.

Meijer, K, Boelee, E, Augustijn, DCM, & Van der Molen, P. (2006). Impacts of concrete lining of irrigation canals on availability of water for domestic use in southern Sri Lanka. Agricultural water management, 83(2006), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2005.12.007]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2005.12.007.

Mitchell, T., Tanner, T., & Lussier, K. (2007). We know what we need: South Asian women speak out on climate change adaptation. London: Action Aid.

Morton, J. F. (2007). The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (50):19680–19685.

Mutekwa, V. T. (2009). Climate change impacts and adaptation tn the agricultural sector: The case of smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 11(2), 237–256.

Mwangi, M. N. (2015). Gender and age analysis on factors influencing output market access by smallholder farmers in Machakos County, Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(40), 3840–3850. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2014.9368.

National Planning Commission. (2009). Nigeria Vision 20: 2020: Economic Transformation Blueprint. Abuja, Nigeria.

NPC. (2006). 2006 Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Priority Tables. Abuja Nigeria: National Population Commission Retrieved from www.population.gov.ng.

Oberhauser, A. M., & Pratt, A. (2004). Women's collective economic strategies and transformation in rural South Africa, gender place and culture. Feminist Geography, 2, 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369042000218464.

OECD. (2008). Gender and Sustainable Development: Maximising The Economic, Social And Environmental Role Of Women.

OECD. (2012). Women’s economic empowerment. The OECD DAC Network on Gender Equality (GENDERNET). Poverty reduction and Pro-Poor Growth: the role of Empowerment.

Ogujiuba, K. (2014). Poverty incidence and reduction strategies in Nigeria: Challenges of meeting 2015 MDG targets. Journal of Economics, 5(2), 201–217.

Oxfam. (2010). Climate Change Adaptation International Research Report.

Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: Conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 399–424.

Ranjan, S. (2006). Occupational diversification and access to rural employment: Revisiting the non-farm employment debate MPRA (pp. 4–8). Germany: University Library of Munich.

Sarfaraz, L., Faghih, N., & Majd, A. A. (2014). The Relationship Between Women Entrepreneurship and Gender Equality. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 2(6), 1–11. 10.11861225–7316-2-6.

Slater, R, Peskett, L, Ludi, E, & Brown, D. (2007). Climate change, agricultural policy and poverty reduction – How much do we know? UK: Overseas Development Institute, .

Terry, G. (2009). Climate change and gender justice. UK: Practical Action Publishing in association with Oxfam GB.

UN.(2011). Towards a green economy. United Nations Environment Programme, Version -- 02.11.2011. Accessed 16 Jan 2018 from https://web.unep.org/greeneconomy/sites/unep.org.greeneconomy/files/publications/ger/ger_final_dec_2011/1.0-Introduction.pdf

UNDESA, (2015) World urbanization prospects. Population division, United nations department of economic and social affairs, United Nations, New York.

UNDP. (1999). Entrepreneurship development. Essentials.

UNDP.(2009). Resource Guide on Gender and Climate Change Retrieved from <http://content.undp.org/go/cmsservice/download/asset/.

UNDP. (2010). Gender, climate change and community-based adaptation. A guidebook for designing and implementing gender-sensitive community-based adaptation Programmes and projects. UNDP, New York, USA.

United Nations Conference On Trade And Development. (2005). The Digital Divide: ICT Development Indices 2004 http://unctad.org/en/docs/iteipc20054_en.pdf United Nations New York and Geneva, 2005.

WEDO (2008). Gender, Climate Change and Human Security Lessons from Bangladesh, Ghana and Senegal. A report prepared byThe Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) with ABANTU for Development in Ghana, ActionAid Bangladesh and ENDA in Senegal. Pp 73.

Women’s Environment & Development Organization. (2007). Changing the climate: Why women’s perspectives matter. New York: WEDO.

World Bank. (2010). World Bank income classifications, reformatted for the 2011 global assessment report on disaster risk reduction. Washington.

Wuyep, S. Z., Dung, V. C., Buhari, A. H., Madaki, D. H., & Bitrus, B. A. (2014). Women participation in environmental protection and management: Lessons from plateau state, Nigeria. American Journal of Environmental Protection, 2(2), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.12691/env-2-2-1.

Zusammenarbeit, DGT. (2010). Climate change and gender: Economic empowerment of women through climate mitigation and adaptation? . In GTZ (Ed.), Working Paper, . Governance and democracy division: GTZ governance Cluster33.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) UK, African Academy of Science (AAS) Kenya and Dr. Sola Asa of Demography Department, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria for their support in the course of this study.

Funding

This research is supported by funding from the Department for International Development (DfID) under the Climate Impact Research Capacity and Leadership Enhancement (CIRCLE) programme. The fund provided by the body assisted in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that the funding body did not make provision for repository WEB LINK, however, the full study report was submitted but datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions