Abstract

This paper seeks to investigate social attributes and factors that influence entrepreneurial behaviors among rural women in Kakamega County, Kenya. A questionnaire survey was administered to 153 rural women entrepreneurs in the County. We found that husband’s moral support was very important for the success of women’s entrepreneurial ventures. At the market place about 77% of the respondents participated in various social activities. These activities fostered business growth through sharing ideas, group customer sourcing and branding of their products. About 97% of the respondents attributed their business success to the help and inspiration from these social networking groups. The respondents were inspired and motivated to entrepreneurship because of these social activities at the market. About 98% of them agreed that they started business to support their families financially. Through this they achieve financial independence and earn respect in their families and society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Sub-Saharan Africa social factors, such as poverty and gender inequality, have greatly affected and will still affect rural entrepreneurship. It is the only region where more than three-quarters of the poor live in rural areas. By the mid twenty-first century, its rural population is projected to increase by 63%. It is the only region in the world where the rural population will continue to grow after 2050 (IFAD 2011). This population growth means a massive expansion of the labor force and a huge pressure on the agricultural sector (Mills et al. 2017).

Many rural farmers have already responded to this trend by developing and diversifying non-farm economic activities. As a result, the overall rural poverty rate declined from 49.7% in 2005 to 40.1% in 2015. Many farmers have engaged in blacksmith, pottery, carpentry and tailoring. In Kenya, this variety of small businesses is called the jua kali sector (KNBS 2017). Here rural women have played important roles (Anthopoulou 2010). They tend to be great networkers with seemingly inherent skills for negotiating. When given opportunities, Kenyan women demonstrated greater ability than men to increase and improve agricultural and business outputs (Davis et al. 2012).

Considering this great resiliency among women, we wanted to find out how Kenyan rural women, who suffer from poverty with low education, have run their businesses and how they can be better empowered to be the future driving force for rural/regional economic developments. So far little research has been done to understand rural women’s entrepreneurial success in rural Kenya. Studies have shown about gender discrimination and poverty in Kenya, but we still do not know much about what motivates these women to engage in businesses (Chelogoi and Nyagar 2013; Amine and Staub 2009; Huysentruyt 2014). We do have a number of studies on women entrepreneurs’ behaviors in developed countries, but not so many on those in African countries (De Vita et al. 2014). Much focus has been placed on urban women rather than rural women (Rutashobya and Nchimbi 1999; Magesa et al. 2013; Gichuki et al. 2014; Brush et al. 2009).

Thus, this paper seeks to investigate social attributes and factors that influence entrepreneurial behaviors among rural women in Kakamega County. This paper is mainly based on the original questionnaire survey and field interviews. In the following discussion, however, we first examine past researches on women entrepreneurship to locate this study within contexts of gender, rural sustainability and entrepreneurship studies. We then introduce the study area so that our case study can be better understood.

Entrepreneurial behavior and gender

Gender differences in network structures and networking behaviors partly influence decisions to start and grow a business (McManus 2001). Anna et al. (2000) argued that in general gender plays a role in business performance or success. After examining gender perspectives on entrepreneurial processes, Bird and Brush (2002) demonstrated that the creation of business venture is gendered in and of itself.

In general scholars have examined the relationship between entrepreneurship and gender from two angles. One examined how gender affects entrepreneurial processes and societal legitimation (Singh et al. 2010). Another angle was to see how entrepreneurship affects the gendered system (Al-Dajani and Marlow 2013). Ahl (2004) suggested that researchers on female entrepreneurs should go beyond gender comparison or the illustration of the subordinated status of women. Somewhat heeding on this research suggestion, this paper seeks to better understand factors that trigger entrepreneurial behaviors among rural women.

Rural women and society

One of the factors that influence female entrepreneurship in Kenya’s rural areas is patriarchal society. Here women generally have been socially subordinated to men. They have been socialized to be passive, non-argumentative, and easy to accept defeat. With the ubiquitous cultural tradition of the bride dowry system, men feel entitled to take dominant roles in decision-making (Ondiba et al. 2017).

Since the 1970s, Kenyan women began to fight against social inequality and laid out the foundation for more women to establish businesses. For example, the late Professor Wangari Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement in 1977 to help improve the lives of rural women. The Movement focused on empowering rural women and girls to foster democratic space and sustainable livelihoods. At that time, they focused on enhancing the basic environment on which most rural women depended on, including water, food, fuel, and medicine. It actively campaigned for planting trees. Although this movement was not specifically related to businesses, it nourished a new generation of women in Kenya who actively pursued available options for their advancement despite gender bias and financial constraints (Muthuki 2006). Among those business women we interviewed in Kakamega County, we saw Maathai’s legacy still exists.

Kakamega County, our study area, is one of these rural areas in Kenya. The Luhya are the majority ethnicity here. Every day, Luhya women busily engage in heavy labor. They fetch fuel wood from the Kakamega forest, attend to household chores and childcare. Many manage family farms alone as their husbands are away to find work in Nairobi. In Kakamega, women do not traditionally own land or other immovable properties. At best, they have usufruct rights, which are restricted by their husbands (Ireri and Ngugi 2016).

Another aspect that influences Kakamega women’s entrepreneurship choice is lack of higher education. Unlike men, few women especially among the older generation received secondary education in Kakamega County. Local people tend to believe that women’s higher education delays women’s marriage (Chege and Sifuna 2006). Many young women get married at early age and become dependent on their husbands’ unstable income. Facing the rising inflation rate and poor living conditions, these rural women start informal businesses to supplement their husbands’ income. Some women also start businesses as they tend to experience less or no harassment from their husbands (Odinga 2012).

Rural women prefer informal businesses that do not require bureaucratic procedures. Typically they sell their farm products. For this type of business, the women pay daily County government market fee at the market place. This fee is very small and affordable. If women want to start formal businesses, they need to obtain business permits at the Kakamega county government office in Kakamega town.

Since 2013, when the Kenyan government promoted the devolution policy and tried to empower local authorities, a number of new opportunities have emerged for local businesses. Some projects aimed to improve infrastructure and created more jobs. County governments have been empowered by the transfer of economic resources from Nairobi. The establishment of Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology in 2007 has allowed more women to sell their products to university staff and students.

Materials and methods

Study area

Kakamega County is in the western region of Kenya with the population of 1,660,651, of which 52% is female (KNBS 2009). It is the second most populous county after Nairobi County and the most populous rural county in Kenya. About 85.5% of the area is rural (Muller and Mburu 2009; Ouma et al. 2011). It has been ranked among the poorest in Kenya with a poverty incidence of 49.2% (KIPPRA 2013).

Kakamega town is the capital and commercial hub of Kakamega County. Its Kakamega municipal market is the largest in the western region. Rural women in Kakamega County come to this town to sell their farm products at the market. Others have also set up kiosks in the central business districts. Wednesdays and Saturdays are the big market days that bring a large number of traders together.

The Luhya tribe has practiced polygamy. A man gains respect based on the number of wives he has. This is partly because only a very wealthy man can afford to pay dowry (bride price) for multiple wives. The dowry was paid in the form of cattle, sheep, or goats. Today, polygamy is no longer widely practiced, but dowry payment still exists in Luhya communities. Wife inheritance is also practiced where a man marries his older brother’s wife when the brother dies (KIG 2015).

Data collection

The main part of this paper is based on field interviews and the questionnaire survey. The questionnaire survey was administered between September and October 2017. Before this, a preliminary field study was conducted in August and September 2017 to make sure that all our questions were understandable within the local context. After this preliminary study, the revised questionnaire was distributed to 153 rural women entrepreneurs at major markets in the county, including Kakamega municipal market, Shianda market, Khayega market and Mumias market (Table 1).

We selected these markets on the basis of the population density and land use classification. These markets are located in Kakamega Central, East and South regions, which have high population densities. They are classified as upper medium ecological zones where intensive small-scale farming is practiced. The majority of markets and shopping centers are located in these regions. (KNBS 2017). Ondiba, the lead author of this article, grew up in this area. In the preliminary survey of 2017, he interviewed Kakamega County to have more thorough information about the County and its economic activities. In conducting the subsequent questionnaire survey, we used the simple random sampling method. In order to better understand the significance of the data we collected, we reviewed past publications on women SMEs, informal businesses and women network groups in Kenya. We also examined reports of the Kenyan government, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and local Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) like the Global Giving Organization.

The questionnaire focused on three sets of questions. The first part covered the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. The second set of questions sought to understand rural women’s relationships and social attributes. Here we tried to understand what triggers their entrepreneurial behaviors. These attributes were considered both in their households and at the market place. The third set of questions meant to assess factors that motivated the respondents to start business ventures. All of the respondents were women entrepreneurs of Kakamega County.

Results and discussions

Socio-demographic features

In the first part of our survey we found that our respondents were mostly younger than 40 years old in nuclear family households. Those between 31 and 40 years old consisted of 43% (Table 2). The age range of 21 to 30 years old had 25% of the total respondents, who were mostly well-trained jobless women. Those between 41 and 50 years old consisted of 27%. These three age groups constituted the vast majority of our respondents. About the marital status, 66% of the respondents were married, and most of them were living in their husband’s rural homes. About 80% of the total respondents had the household size from one to five members. The major component of these households was the children of the respondents while some lived with their younger siblings. Households with greater than five members were mostly polygamous. The majority of the respondents had monthly revenue of between 20,001 to 30,000 Kenya shillings. This monthly income in the rural areas comfortably put rural women in middle class income earners. Most of them were able to cater for the household expenses, expand their businesses and support their friends through the chama.

The education background of the responded varied, but tended to be up to the secondary education level. Those respondents without formal education were about 5%. These women did not adequately read and write, but they could fluently converse and count in the local language and basic swahili. About 31% had received up to primary education, and 21% received secondary education. Most of these women also could read, write and converse in Swahili with little English. They had also undergone informal training and acquired vocational skills that include basic accounting and computer skills, tailoring, and catering. The training was typically initiated by their social groups or chama as well as religious groups and NGOs like the Global Giving Organization. About 21% of the respondents had university education. Most of them had engaged in business as professionals or as part-time workers.

Personal relationship and social attributes

The second part of the questionnaire aimed to understand what attributes drive women’s entrepreneurship behaviors. In each of the age groups, about 66% of the respondents were married with families. Those in the age group between 31 and 40 years old consisted of 34% and those between 21 and 30 years old did 14%. The age group between 41 and 50 also constituted 14% (Table 3).

Some women would sell farm products at the roadside near their homes and later go to a market place to sell more. As mentioned above, the establishment of the Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology and the county government headquarters in Kakamega town increased business opportunities for women, including the respondents.

However, rural women in Kakamega cannot engage in market business without permission from their husbands. They are often discouraged to engage in any activities outside their homes. Social restrictions regarding networking with men in business is a common practice among the Luhya community. Traditional men sometimes find women’s economic independence and success as a threat to male dominance.

Back to our survey result, single women constituted the second largest group (19%) among the respondents (Table 3). Most of them were young fresh graduates who engaged in business due to lack of work experience. Others had acquired practical skills by receiving training from tertiary institutions. Some of them had formed business clubs and partnerships with their former schoolmates.

In the questionnaire, we asked the married respondents to rate their spouses’ support towards their entrepreneurial activities. About 59% of them responded that the support of their spouses was either good or very good (Fig. 1). Only about 15% of the respondents rated the spousal support as poor or very poor. This shows that husband’s support motivated women in operating businesses. Nevertheless, they agreed that it was not easy to obtain support from husband.

This support from husband does not mean financial support. The respondents who had spousal support said that it was not possible for their husbands to fund their businesses because their husbands were already burdened with household expenses. In our field visits, we also observed that women entrepreneurs were generally discouraged from doing business if they asked their husbands for money.

Social attributes at the market

At the market place, rural women customarily establish networks that often inspire them to find new business opportunities. They come to the market to sell their family farms products. Occasionally they acquire goods from outside to sell. For example, they procure fish from Lake Victoria and fruits from the central region of Kenya to sell at the Kakamega market. Kakamega women’s active participation in market transactions is also seen in our questionnaire survey result. About 77% of our respondents had participated in various social activities at the market place (Table 4). These activities range from family level to community one.

Women at the market place engage in several social activities, of which chama is the most famous one. Their social activities include organizing meals together, cleaning the market and also assisting funeral or wedding ceremonies. Chamas are more structured rural women social networking groups. About 86% of the respondents belonged to at least one chama at the market place (Table 4). Our questionnaire survey found that each chama had its founding principles, objectives and purposes. The purposes range from financial ones, asset acquisition, welfare or regulatory. The majority of our respondents had joined chama for financial purposes.

Similar to this discussion on chamas, Jack and Anderson (2002) argued that rural women often demonstrated strong social networking skills. Rather than competing, many rural businesses embrace the concept of cooperation, and draw upon their potential strengths to identify niche markets (Steiner and Cleary 2014). Our questionnaire survey similarly demonstrated that about 97% of the respondents attributed their business successes to these social networking groups. About 93% of the respondents had obtained business inspiration by meeting people at the market and participating in social networking activities. They were motivated when they saw successful rural women entrepreneurs who belonged to the same social class and had overcame similar challenges.

Motivating factors

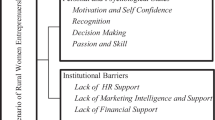

The third part of our survey aimed at assessing factors that motivated Kakamega rural women to start business ventures. Figure 2 shows that 98% of the respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that they started business to support their families financially. Traditionally, men were expected to meet all the financial needs of their families. However, due to the rising inflation rate, unemployment and growth in household sizes, rural women decided to support their husbands.

Women also wanted to achieve financial independence. About 97% of the respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that they started business to own property. As mentioned before, the Luhya traditionally restricted women to inherit property, but our field observation revealed that their enterprises, which are legally gender neutral, can help women buy land, houses, cars and other properties.

Another important factor was women’s desire to maintain social networks. About 84% of the respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that they started business for networking. Social groups at the market place provide a platform for them to share their family experiences and learn from others. About 50% of the respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that they engaged in entrepreneurship to earn respect in society. They also earned respect and trust from their husbands when they supported their husbands financially.

Conclusion and recommendation

From this research we conclude that social characteristics both at household and market significantly affect the decision of rural women to start and operate businesses in Kakamega County. Among married women, spouse’s support was an important factor to engage in business. At market, rural women established social networks like chamas that often inspired them to find new business opportunities or improve their on-going businesses. About 86% of the respondents belonged to at least one chama and about 97% attributed their business success to these chamas. Their desire to own property also motivated them.

Reflecting on these findings, we recommend further research on business behaviors, perceptions and factors that influence business performance and sustainability of rural women entrepreneurs. The socio-cultural challenges rural women face needs further investigation. To empower rural women in expanding their business opportunities, chamas may play important roles in the future.

Abbreviations

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental Organizations

References

Ahl, H. (2004). The scientific reproduction of gender inequality: A discourse analysis of research texts on women's entrepreneurship. Liber: Ola Hakansson publishers.

Al-Dajani, H., & Marlow, S. (2013). Empowerment and entrepreneurship: A theoretical framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 19(5), 503–524.

Amine, L. S., & Staub, K. M. (2009). Women entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa: An institutional theory analysis from a social marketing point of view. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 21(2), 183–211.

Anna, A. L., Chandler, G. N., Jansen, E., & Mero, N. P. (2000). Women business owners in traditional and non-traditional industries. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3), 279–303.

Anthopoulou, T. (2010). Rural women in local agro-food production: Between entrepreneurial initiatives and family strategies. A case study in Greece. Journal of Rural Studies, 26(4), 394–403.

Bird, B., & Brush, C. (2002). A gendered perspective on organizational creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 41–65.

Brush, C. G., De Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender-aware framework for women's entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24.

Chege, F., & Sifuna, D. N. (2006). Girls’ and women's education in Kenya. Gender perspectives and trends. 91, 86–90.

Chelogoi, K., & Nyagar, A. (2013). The effects of the microfinance institutions on small scale business growth: A survey of Uasin-Gishu County, Kenya. Journal of Finance Management, 56, 13402–13406.

Davis, K., Nkonya, E., Kato, E., Mekonnen, D. A., Odendo, M., & Miiro, R. (2012). Impact of farmer field schools on agricultural productivity and poverty in East Africa. World Development, 40(2), 402–413.

De Vita, L., Mari, M., & Poggesi, S. (2014). Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. 2013. European Management Journal, 32, 451–460.

Gichuki, C. N., Mulu-Mutuki, M., & Kinuthia, L. N. (2014). Performance of women owned entreprises accessing credit from village credit and savings associations in Kenya. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 4(1), 16.

Huysentruyt, M. (2014). Women’s social entrepreneurship and innovation. OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Working Papers, 2014/01, OECD.

IFAD (2011). International Fund for Agricultural Development, rural poverty report, Facts and figures. https://www.ifad.org/web/knowledge/publication/asset/39176373. (Accessed on 12th February 2018).

Ireri, J. W., & Ngugi, A. (2016). Factors influencing land ownership by women: case of Khwisero constituency, Kakamega county. Kenya: Department of extra mural studies, University of Nairobi. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke. (Accessed on 6th March 2018).

Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487.

KIG (2015) Kenya Information Guide. http://www.kenya-information-guide.com/luhya-tribe.html. (Accessed on 7th March 2018).

KNBS. (2009). Kenya national bureau of statistics. In 2009 population and housing census. https://www.knbs.or.ke/census-2009/. (Accessed on 7th March 2018).

KNBS. (2017). Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Basic Report on Well-being in Kenya. Based on Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey - 2015/16. https://www.knbs.or.ke/publications/?wpdmc=2015-step-survey. (Accessed on 6th June 2018).

Magesa, C., Shimba, C., & Magombola, D. (2013). Investigating impediments towards access to financial services by women entrepreneurs: A case of Arumeru District. Development Country Studies, 3(11), 105–115.

McManus, P. A. (2001). Women’s participation in self-employment in western industrialized nations. International Journal of Sociology, 31(2), 70–97.

Mills, G., Falconer, R., and Musker, S. (2017) Ghana: Realising Africa’s agriculture potential. Daily Maverick (newspaper). https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/Africa. (Accessed on 10th April 2018).

Muller, D., & Mburu, J. (2009). Forecasting hotspots of forest clearing in Kakamega Forest, Western Kenya. Forest Ecology and Management, 257, 968–977.

Muthuki, J. (2006). Challenging patriarchal structures: Wangari Maathai and the Green Belt movement in Kenya. Agenda, 20(69), 83–91.

Odinga, E. O. (2012). Challenges facing growth of small and medium enterprises owned by women in Kakamega Municipality. University of Nairobi: Doctoral dissertation.

Ondiba, H.A., Matsui, K., and Karanja J. M. (2017). Women’s Success Attributes in Small and Micro Enterprises in Kenya. 3 rd International Conference On Regional Challenges To Multidisciplinary Innovation. (5-6th October, 2017 Nairobi, Kenya.) (3), 10–15 (Oral Presentation). http://globalilluminators.org/conferences/rcmi-2017-kenya/rcmi-full-paper-proceeding.

Ouma, O. K., Stadel, C., & Eslamian, S. (2011). Perceptions of tourists on trail use and management implications for Kakamega Forest. Western Kenya. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 4, 243–250.

Rutashobya, L. K., & Nchimbi, M. I. (1999). The African women entrepreneurship: Knowledge gaps and priority areas for future research. Rutashobya: LK and DR Olomi.

Singh, S., Mordi, C., Okafor, C., & Simpson, R. (2010). Challenges in female entrepreneurial development – A case analysis of Nigerian entrepreneurs. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 18, 435–460.

Steiner, A., & Cleary, J. (2014). What are the features of resilient businesses? Exploring the perception of rural entrepreneurs. Journal of Rural Community Development., 9(3), 1–20.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my great appreciation to Prof. Kenichi Matsui for his guidance and professional advice during this research. I am greatful to the reviewers and editor of this article for the valuable input. Special thanks to Vivian Namayi of Soroptimist International women club for helping me access many rural women in Kakamega County.

Funding

No funding was received for this research, the authors catered for the research expenses by themselves.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HO corresponding, Conceived and designed the research with the guidance of the co author MK, Together with the co author, we designed the methodology and questionnaire used for the field survey and interview. Collected data both primary and secondary data. Performed the data analysis Wrote the paper, KM ,Co author, Revised and guided the research design, Designed the methodology and questionnaire used for the field survey and interview together with the corresponding author. Helped in data analysis and interpretation. Revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ondiba, H.A., Matsui, K. Social attributes and factors influencing entrepreneurial behaviors among rural women in Kakamega County, Kenya. J Glob Entrepr Res 9, 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0123-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0123-5