Abstract

Bangladesh consists of wetlands that pose great threat to the public primary education services. BRAC (Building Resources Across Communities) - a non-governmental organization, therefore, took the opportunity to serve unprivileged children by implementing boat schools model in solving barriers of such uninterrupted education. This case focuses in dealing those threats through the usage of prototype boat schools as a vehicle of social innovation for particular regional development. Thus, BRAC boat schools appear to bring blessings for children in accessing their basic right of education to enlighten the society. The impact of boat schools in education is examined to create positive socio-economic changes. However, this study highlights a brief analysis of the context based on diverse stakeholders and their perspectives to contribute in the theoretical endeavor of social innovation in educational context. It inevitably demands a promising avenue of interests to devise further research on the compatibility of social innovation in education to gear up status of an impoverished society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Bangladesh is located in the northeastern part of South Asia and covers an area of 147,570 km2 with population of 156.19 million (July 2016 estimate). It is almost entirely surrounded by India, except for a short southeastern frontier with Myanmar and a southern coastline on the Bay of Bengal (Chowdhury et al. 2013). The most significant feature of the land is the extensive network of large and small rivers that are of primary importance to the socioeconomic life of the nation (Bose 2013). Compared with other countries in the region, the landmass that constitutes Bangladesh is relatively new (Chowdhury et al. 2013). Approximately, one-third of the total land in Bangladesh is considered as a bowl shaped shallow depression with special hydro ecological characteristics (Master Plan 2012). People are economically dependent on resources and accommodate their subsistence adjacent to the environment. Density of population in region is 987 per square kilometers (Master Plan 2012). One of the greatest distresses in the area of Bangladesh, consequently, is the figures relating to the education. The present status of primary education has not reached a satisfactory level in terms of both quality and quantity. Despite having a mainstream primary education policy from the government side, achieving full enrollment and completion of primary education for children remains a serious challenging issue.

To address these needs, BRACFootnote 1 employs local resources and labor to build modern techno friendly boat schools (‘Shikkha Tari’) for communities where waterway is the only means of communication for most of the time in a given year. It is a novel innovative step to bring about ‘Shikkha Tari’ (boat of education) operated under the BRAC education program in an inundated area to lessen the number of school dropouts and enhance the school learning environment (Ahmed et al. 2016). These boat schools are now promising a range of educational and social services in developing socio economic base for a disadvantaged group of people in Bangladesh.

This paper provides an overview of education for children in Bangladesh with strategic challenges and policies to address them. It begins with a discussion by shedding light in the education scenario of children in Bangladesh and highlights the causes behind poor literacy growth in this sector. Then, it focuses on the theoretical overview on social innovation in education. The paper applies a case study approach where the structure, operations, and challenges of BRAC Boat Schools Education are discussed in detail.

Education for children

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) states, “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages.” Moreover, it states, “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms (Article 26).” Education for All (EFA) is an international initiative first launched in 1990 to bring the benefits of education to “every citizen in every society.” To realize this aim, a broad coalition of national governments, civil society groups, and development agencies such as UNESCO and the World Bank Group committed to achieving six specific education goals.Footnote 2

The Government of Bangladesh has shown commendable zeal whilst establishing laws to promote the quality, quantity and accessibility of primary and secondary education in the country since its liberation. The Primary Education Act (1981), the Primary Education (Compulsory) Act (1990), and later the country’s first National Plan of Action (NPA) on Education for All (EFA) (1990) are all legal endeavors carried out by the government to both ease access to, and boost enrollment of primary and secondary education (Ahmed et al. 2007).

A few of the causes for this tardy literacy growth rate can be associated with the following factors:

Impact of Flash Flood: It is characterized as a flood prone area filled with water for almost six to 7 months in a year. During this time, no education activities are actually carried out as people’s basic living conditions are conspicuously disturbed (Ahmed 2013). Schools are being used as an alternative shelter of emergency during disasters. Therefore, children remain away from education for a long period of time to maintain continuity in learning.

Abject Level of Poverty: Most often, people cannot fulfill their basic amenities of life due to the constraint of natural calamities and social exclusion. Due to the economic hardship, indigenous people cut off expenditure on education for their children to allocate a big chunk of money on securing food requirements (Chowdhury 2005). Geographical isolation and uneven distribution of income are two crucial factors to take in account for people in calculating the opportunity cost of going to school for their children. As these families are bound hand-to-mouth, children above age five are often put into day labor jobs. Thus, after birth, these children are never given the privilege to invest in formal education as their families perceive it as a lengthy process with too little instant return. According to their simple logic, the more hands they have to bring money in now, the greater are their chances of survival.

Deficit Number of School: Despite the national education policy of 2010 in Bangladesh that emphasizes on ensuring minimum one school in each village; the present scenario in regions reveal a distressing picture. Very few schools are constructed to serve the demand of primary education in based society (Roy 2015).

Poor Communication Infrastructure: Inadequate number of primary education institutions in a remote locality forces people to send their children to schools which are located far from their community. Considering inferior quality of transportation modes, high transportation cost and security issues, people usually restrain their children from going to school. Girls are more restricted as their parent fear for their safety while traveling across distances. Therefore, disparity in literacy rate among girls and boys is intense in primary education (BRAC 2016). The enrollment rate of primary education of girls is significantly lower and the dropout rate is higher than boys. Besides, inflexible communication also causes higher absenteeism and late arrival of teachers and staffs who mostly accommodate their living in the adjacent urban area (Alamgir 2015).

Indigent School Environment: Most of the schools in region are yet standing out of electrical connection. Drinking water and sanitation facilities have to be upgraded to attain minimum standards in the school environment (Raju 2013). In most instances, student friendly and learning oriented school ambiances are absent for an effective and efficient operation. Since students are deprived of recreational activities in school, it decreases their motivation and interest in continuing further education.

Internal Dissonance in School Management: The public education sector in Bangladesh is very poorly regulated. Rarely, haor schools are visited and monitored by Upazila Education Officers (also known as Thana Shikkha Officers or sub-district education officers) in any particular academic calendar. As a result, all the administration, staffs and teachers are accustomed to shrink their responsibilities. Scarcity of education materials, lack of experienced teachers and low teacher-student ratio are very pressing issues in schools to confirm quality management in serving education as a public good.

Literature review: Social innovation in education

The necessity of innovation is as old as the history of human civilization. Currently, innovations are profoundly becoming the engine of social change and adaptation for ensuring a better society. It is the society upon which any type of innovation centers on creating social impacts to name it social innovation. The notion of social innovation is articulated in diverse disciplines of public administration (Adams and Hess 2008; Guth 2005), a social movement (Henderson 1993), management (Clements and Sense 2010; Drucker 1987), social psychology (Marcy and Mumford 2007; Mumford and Moertl 2003; Mumford 2002), economics (Pol and Ville 2009), and social entrepreneurship (Lettice and Parekh 2010; Short et al. 2009). Under the multiple conceptual frameworks, it seems to be arduous to reach a comprehensive meaning of the subject considering paramount complexities underlying it.

Mumford (2002) defined social innovations as the creation and usage of new ideas about people and their interactions within a social system. In fact, social innovation appears to represent a particular form of creativity, leading to the formation of new methods and forms of social interaction (Gryskiewicz and Epstein 2000; OECD LEED Forum on Social Innovations 2000).It is assumed to create positive impact on broader parameters like sociological, environmental and economic aspects. Rooted in social challenges and needs, social innovation should be capable of upgrading the social status of an impoverished community (Nussbaumer and Moulaert 2004). It is further argued as a mechanism of devising innovative solution landscape for a social problem to advance in social issues and demands (Phills et al. 2008). Here, innovation is not only relevant for technology-intensive context, but also operating within a traditional context, which, for instance, rely on services to build their innovative capacity (D'Ippolito and Timpano 2015). Hence, the role of a social entrepreneur as a humanitarian agency and a social innovator has been greatly emphasized in the literature (Bacq and Janssen 2011; Nicholls 2010). However, social innovation gets its momentum through the process of institutionalization of innovation. Institutions are aiding to facilitate and diffuse practices of a particular social innovation in dispersed communities (Mulgan et al. 2007).

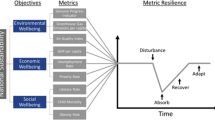

Structural determinants can catalyze the process of social innovation in bringing social reformation. All the social actors’ engagement in constructing complex social system is resulting from pattern of social interactions and conflicting interests among them. Therefore, interactions between individual agent, institutional structure and social system are advocated to newly define a social relation and structure for conceptualizing the idea of social innovation (Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006). In a reality, where sustainable changes are inevitable to remain with social dynamism, deployment of social innovation as a vehicle of change in a particular context leads to positive socioeconomic gear up (Heiskala and Hämäläinen 2007). A systematic change takes place to affect all spheres of meanings, practices and structures of a society through social innovation.

Regardless of the great array of views through which the concept of social innovation can be explained and analyzed, an integrative social innovation framework is proposed by Ümarik et al. (2014) that is capable of addressing educational change or innovation. It is built on a common set of characteristics among prevailing approaches of social innovation. Five main traits are outlined that have to be manifested in a social innovation under educational context: trigger of change, change agents, social mechanism, social implication or basis of legitimacy, and social gain. This model views social innovation as a deliberative process of facilitating educational change or innovation that is generated from a concrete logic to fix a problem or meet the social need by a social agent through social mechanism and implication to attain certain social outcome or gain (Loogma et al. 2013).

Educational change or innovation has a vast impact on society; similarly, change in society can also claim educational innovation mandatory to adopt with the new structure of the society. Both cases, social innovation explores the scope of a new avenue to find its connection with educational affairs. Social innovation in educational settings can be illustrated in a unique delivery system of education services to degrade educational exclusion and inequality (Martellucci and Thum 2013). Building on collaboration of different stakeholders and flexible schooling programs, community school is presumed to be the paragon of a social innovation in education (Furco 1996; Vleva 2012).

Educational challenges like student disengagement, diversity, school violence, globalization, environmental devastation and technological advancements can be resolved by delineating a sustainable and socially innovative solution (Conrad 2015). Thus, social innovation in education has a wider scope to create influence for ensuring innovative learning environment, organizing and managing schools, discovering new ways of teaching, learning and collaborating with local communities. Consequently, it can have further impact on broadening social scope of development through enabling educational reformation (Martellucci and Thum 2013). When top down initiatives fail to address some local problems of education, grass root activities getaway to find the root of social innovation that can also be transferred in another locality confronting similar problems.

Method: Case study approach

The method of case studies is, of course, general and has been extensively followed in many past studies (Ahmed 2007). Two streams of researchers’ group are found to view case study from different lenses. Stake (2005) proposed “a case” itself is a point of the object to be studied, whereas Simons (1996) argued it as a method that commonly involves different assumptions about how a study should be conducted from those underlying approaches.

However, in this study, a case study approach is employed as a method of study to explore the educational context in a particular school setting. Rationale of choosing this method is justified in any explorative investigation (Yin 2009) that focuses on an instance of the thing (Denscombe 1998). In a given research condition, a case study is well established to derive answers of “how” and “why” questions to generalize the phenomenon. The case study is widely used as a research method to examine an entity and a context under which the entity belongs to. It is worthy enough to get the optimum outcome from a research by applying case study when the focus of the study is not typical, but something unusual, unexpected, covert, or illicit (Hartley 1994).

The idea of social innovation in education rents for searching an in depth meaning and is positioning itself in a beginning phase of conceptual development. Thus, it becomes one of the most viable strategies to explore ways to connect with social innovation in educational reality by applying the case study design. Single case design would be followed instead of multiple case designs to understand the organization (BRAC boat schools) questions more deeply and rigorously without any confusion. However, the integrative framework of social innovation (Umarik et al. 2014) is adapted to measure the concept of social innovativeness of BRAC boat schools. Secondary data sources including documentation, archival records, daily newspapers, BRAC website, etc. are utilized to design the case in hand.

Case: BRAC boat schools in Bangladesh

Water vessels such as boats are an ancient and traditional mode of transportation in the Bengal delta. The settlement and the way of life of human civilization in rural Bangladesh are influenced by an extensive river system of the country (Zaman 1991) to notice the importance of a boat in rural communication. However, boats are becoming obsolete with the aim to seek human settlement in the culture of Bangladesh; revolution has been taking place in the process of boat production since 1980 that allows techno enabled less costly and modernized version of boats compared to previous backdated ones. As previously mentioned, boats are not new to the culture of Bangladesh, but using boats as schools is something that can be considered as a vehicle of social innovation.

Background of BRAC

BRAC (Building Resources Across Communities) was founded in Bangladesh, just after her independence in 1971 by (knighted) Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, who, like most antagonists of success stories, started off the project with very humble means. The 1971 war had an important role in starting national development processes (Chowdhury et al. 2013) which led a few individuals to work for BRAC rehabilitation projects in the remote north-eastern parts of Bangladesh. Later on, the founding operators of BRAC shifted their sights from a short-term relief effort to a long-term, more withstanding existence dedicated to fending off the persistent nature of endemic poverty in the country (Chowdhury and Bhuiya 2004).

Since its inception, the entire BRAC endeavor has gained fast momentum through innovative ways of expansion and operation. Its initial projects to heal the ailments of war in the nation, however, are boldly supported by the government. Activities such as providing mainstream microfinance and social support services that contains health, nutrition and livelihoods (vocational) training are BRAC’s areas of expertise (Kabeer et al. 2012). Currently, BRAC boasts a multitude of diversified projects that zero-in on an equally numerous host of issues; those which stunts human and economic progress in Third-World Nations. BRAC-owned organizations are in operation in all of the 64 districts of Bangladesh, as well as in Liberia, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, the Philippines, and a plethora of other such developing nations in the Southern Hemisphere.

BRAC boat schools education

After gaining enough momentum from its earliest projects (i.e. the health and nutrition program, the microfinance schemes, etc.), BRAC realized another chaotic obstacle to the development of rural Bangladesh. In a post-war economy with rampant population growth, there were less than 37,000 loosely-organized schools to cater to the entire nation. This situation was extremely problematic due to an access in education which in turn threatened the national growth and progress. Upon reaching this conclusion that strengthening the foundations of the nation’s intellect has equal precedence to its healthcare and finance systems, BRAC set out to functionalize its extra-governmental education system in 1985. Presently, BRAC prides itself in achieving the milestones of being the largest secular education system in the world by having 10 million local students (The Daily Star 2015) and 9 million global students (BRAC 2016) enrolled in around 38,000 primary and pre-primary BRAC schools. It has 9.51 million graduate students to highlight its effort in improving education index.

BRAC Education Programme carries out its activities in accordance with a five-year plan and is active in five major areas, comprising of NFPE, pre-primary schools, the Adolescent Development Programme (ADP), the Multi-Purpose Community Learning Centres, and the Mainstream Secondary Schools Support Initiative (Chowdhury and Bhuiya 2004). However, the idea of a floating school in combating local problems is one of the unique approaches initiated by BRAC in delivering education services to remote areas. High impact and low cost BRAC boat schools were inaugurated in October 22, 2012 as a result of a partnership between EAC (Educate A Child) and BRAC to promote quality primary education for unprivileged children of Bangladesh (The Daily Star 2012). It is a remarkable, innovative step to bring about “Shikkha Tari” operated (as shown in Figs. 1 and 2) under the BRAC education program. Initially, over 13,000 out of school children were targeted to allow them a second chance of coming back to school by launching 452 boat schools across 14 districts of Bangladesh (BRAC 2016).

The defining point of BRAC boat schools is educational services that distinguish its talents in setting goals and abiding by them. Unlike most other government and/or privately owned institutions, BRAC boat schools strictly monitor a set of quality-control factors and a solid level of organization. Among its set of quality control criterion, some of the following are included below:

-

◦ BRAC develops textbooks and other educational materials for up to grade 3 and government national curriculum textbooks are used in grades 4 and 5.

-

◦ One teacher maintaining a maximum of 30 students.

-

◦ A locally-resided female teacher of at least 10 years of experience in the field of school teaching, as well as a senior school certificate.

-

◦ At least 60% of class comprising of female students.

-

◦ Flexible school scheduling according to needs.

-

◦ Special attention to children with special needs.

-

◦ No homework for students since most of their parents are unable to assist them.

(BRAC, 2016)

BRAC boat schools make a conscious commitment to provide all-inclusive education that is accessible for all. For example, every class accommodates a ratio of 40% males and 60% females, so as to inspire the female population towards a greater push at receiving an education. Furthermore, community workers actively partake in awareness programs that are primarily geared towards families, such as the ultra-poor, that would otherwise never consider any form of formal education for their young. As a result, BRAC boat schools are now supporting more girls beyond the age of five than any other NGO that specializes in free and accessible education.

BRAC boat schools are mainly 12.8 m in length, 3.2 m in width and 1.9 m in height. They are designed to serve dual purposes: as a school boat and as a classroom. At a time, it can accommodate 30 students in a classroom. The ambiance of classroom of a boat school is unique and inspirational enough to display several paintings and writings, handmade flowers, alphabets, word lists and timetables. BRAC developed textbooks are recommended for students up to class three and national curriculum textbooks are followed for students in grades four and five (Ahmed et al. 2016).

BRAC boat schools makes an effort to ensure proper dietary plans for the pupils alongside medical attendance which is made readily available for students with special needs. Furthermore, in the pre-education level, children are exposed to “fun”, western-styled preschool activities and an average of two and a half hours of extra-curricular community activity after school (BRAC 2016) to engage their interest in learning and build enthusiasm in investment behind education. BRAC’s art of designating “grades” in the education system has been giving impoverished students a sense of direction ever since its inception (i.e. Pre-primary school, primary school, tracking of transfers throughout secondary school in government-subsidized institutions, and university).

Moreover, the education is completely free; as the smallest fees charged on education may become a burden to pay for the indigent families of children. Hence, BRAC insists it immoral to take any payment from the needy patrons of people. Moreover, monthly parent-teacher meetings in the BRAC floating schools allow guardians to increase awareness about the child’s performance, health, personal hygiene, nutrition, parenting, and moral values (Chowdhury 2015). The simple comfort of children in terms of eliminating boat fair costs of schooling is translated in broadening the opportunity for availing lessons from a skilled teacher on a regular basis irrespective of variation in natural calamities (Dhaka Tribune 2013).

Discussion

Social innovation seeks new answers to social problems by identifying and delivering new services that improve the quality of life of individuals and communities (OECD LEED Forum on Social Innovations 2000). It requires ideas and solutions that are based on identifying a limited number of manageable key causes. This characteristic of successful social innovations is nicely illustrated in this case study (Mumford 2002). Apparently, social innovation requires expertise in the system at hand but the social innovator must be able to transcend existing wisdom to push a system to adapt new models (Mumford and Moertl 2003). Here, BRAC boat schools have committed itself to relieving Bangladeshi public primary and mass education of its ailments, and thus filling in the vital void of producing educated individuals regardless of their socioeconomic circumstances. BRAC boat schools owe their results to one fact in particular – they patch together all the shortcomings of government funded education services as well as that which is provided by many private institutions. A prominent lack in setting quality standards for the curricula as well as the modes in which it is taught, teaching standards, class sizes, adequate extra-educational support, and mentoring are all promoted through BRAC boat schools as a prototype of social innovation to deliver public education free of cost to the poor children.

It seems unacceptable that children cannot access their educational rights due to some unprecedented factors mentioned in education. The logic of emergence for launching “Shikkha Tari” is thus considered to be a vigorous social innovation for mitigating the social issues confronted by locality. Certainly, BRAC boat schools target an impoverished area to ease the access of education for unprivileged children that can ameliorate the socioeconomic status of victims (Nussbaumer and Moulaert 2004). The schools are operating under the BRAC education program and are initiated by the already established NGO. Therefore, acting as an agent of gearing social innovation, BRAC institutionalizes the idea of a boat school in a short span of time to implement it in a real context (Mulgan et al. 2007). BRAC has been operating in Bangladesh since 1971 and it has already gained profusion of public esteem all over Bangladesh for its wide spread services target to people laying at the bottom of the pyramid in the society. It creates acceptance in the perception of people to catalyze the educational paradigm change in based society. A unique delivery system of education along with different school structure is portrayed in BRAC boat schools that are well adapted to the changing circumstances in filling the basic demand of a distress community. Thus, BRAC boat schools are arguably a vehicle of social mechanism of change (Heiskala and Hämäläinen 2007).

Moreover, the BRAC boat schools provide a platform for communities to interact with each other and with institution to increase awareness and knowledge on diverse practical subjects that have vast social impacts in creating sustainable livelihood options. It becomes a prominent center of community networks and knowledge exchange protocol for community members of society to create newly define sustainable social structure and practices (Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006). Hence, it creates structural change in the society by simply using a boat as a school and a school boat where the monthly parental meeting allows the change to happen in the attitude and practical knowledge of people.

Upon analysis, it can easily be generalized that the five characteristics feature (trigger of change, change agent, social mechanism of change, social implication and social gain) proposed in integrative model of social innovation (Umarik et al. 2014) in educational change or reformation are clearly demonstrated in BRAC boat schools program to define it as a social innovation under the provision of educational change or reformation.

Results: contributions and social implications

Social innovation is potentially system changing theme. It carries the notion of creating something novel and robust to add more value. Here, the objective of the floating schools (Shikkha Tari) is to provide free and accessible primary education to impoverished children of areas in Bangladesh. To achieve this objective, the organization has taken various steps. It provides a platform for education where textbooks and supplies are available and pursues an active learning environment to generate interest for studying amongst the young children. Moreover, as the children receive pick up and drop off services, it presents an ideal situation for both parents and children who were previously unable to attend school due to transportation issues.

Hence, the students greatly appreciate the services as it allows them to attend school whereas they would have either stayed at home or helped their parents with household chores. Likewise, attending school also prevents the children from being influenced by bad company and engage in illegal activities. Consequently, providing children with the opportunity to study, BRAC boat schools have increased literacy and reduced dropout rates and absenteeism amongst the children (as shown in Fig. 3). Moreover, it has encouraged woman empowerment as the school dropout rate for girls particularly saw a remarkable reduction. Besides, it has created opportunity for jobs and improved local economic development in the regions as the boats are locally manufactured and the pickup and drop off services carried out by locals. These boat schools collaborate with local community members for facilitating an innovative learning environment in creating a passion for knowledge in the impoverished regions.

Furthermore, the concept of boat schools can be used and applied to create boat communal places where communities may be able to receive basic facilities where unavailable. In addition, further development to improve the infrastructure of the boat models is crucial to the overall development prospect. For future prospects, the organization should focus on improving its services and eventually extend the all-inclusive education to cover all grades of primary education which increase the amount of children attending boat schools. Through education and intellectual training, extension would allow more children to develop self-reliance and lead an enhanced quality of life. Moreover, it would further increase awareness about the importance of education among the locals.

Conclusions

BRAC boat schools are best illustrations of a grass root initiative social innovation in education considering limitation of top down approach in reaching a gray zone like based society to deliver basic education services in Bangladesh. This model is capable of combating factors that are responsible for interrupting education of children. However, future impact in terms of secondary enrollment or vocational schooling of children cannot be ensured by those particular BRAC boat schools operations.

Though this particular case conforms to the integrative model of social innovation conceptualized by Umarik et al. (2014), it does not necessarily grasp the whole facets of social innovation in a single case. Perceptions of participants are also not examined in this study to reveal the underlying position of all stakeholders’ interests in accepting BRAC boat schools as a prototype of social innovation in education. A meticulous focus discussion is required to assess the impacts of boat schools program in different layer of society. Moreover, the transferability of newly created social practices and social structure by BRAC boat schools’ operation as an archetype of social innovation to geographically dispersed locations remain unexplored to reach the completeness of discussions.

The case of BRAC boat school continues to focus on how social innovation can take place in elementary and primary education; in particular, the way in which process applied to improve literacy and enroll high number of students. In this sense, future research would be supplementary for providing a holistic picture of social innovation in educational ground that happens to prove its worthiness in solving educational problems of a developing country like Bangladesh. Perhaps, an effective dialogue between top down and bottom up social innovation is essential in the process of theoretical conceptualization of social innovation in education. In addition, exchange of knowledge and methodologies on the topic among different stakeholders can be very fruitful in deriving unique understanding and approach of social innovation in education (Igarashi and Okada 2015).

Notes

Currently, BRAC is known as Building Resources Across Communities. It was formerly known as the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee and then as the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee. BRAC was initiated in 1972 by Sir Fazlé Hasan Abed in the district of Sunamganj as a small-scale relief and rehabilitation project to help returning war refugees after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. BRAC is present in all 64 districts of Bangladesh as well as 14 countries in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. BRAC employs over 111,000 people, approximately 70% of whom are women, reaching more than 138 million people.

In 1990, over 150 governments adopted the World Declaration on Education for All (EFA) at Jomtien, Thailand to boost efforts towards delivering the right to education. Again, in 2000, the World Education Forum in Dakar, Senegal reaffirmed this commitment and adopted the six EFA goals that run to 2015:

-

1.

Expand and improve comprehensive early childhood care and education, especially for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged children.

-

2.

Ensure that by 2015 all children, particularly girls, those in difficult circumstances, and those belonging to ethnic minorities, have access to and complete, free, and compulsory primary education of good quality.

-

3.

Ensure that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life-skills programs.

-

4.

Achieve a 50% improvement in adult literacy by 2015, especially for women, and equitable access to basic and continuing education for all adults.

-

5.

Eliminate gender disparities in primary and secondary education by 2005, and achieve gender equality in education by 2015, with a focus on ensuring girls’ full and equal access to and achievement in basic education of good quality.

-

6.

Improve all aspects of the quality of education and ensure the excellence of all so that recognized and measurable learning outcomes are achieved by all, especially in literacy, numeracy and essential life skills.

The World Bank (2014)

-

1.

References

Adams, D., & Hess, M. (2008). Social innovation as a new public administration strategy, in 12th Annual Conference of the International Research Society for Public Management (IRSPM XII).

Ahmed, J. U. (2007). Research issues in case study method: Debates and comments. AIUB Journal of Business and Economics, 6(2), 1–14.

Ahmed, J. U., Ashikuzzaman, N. M., & Nisha, N. (2016). Understanding operations of floating schools: A case of Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha in Bangladesh. South Asian Journal of Business and Management Cases, 5(2), 221–233.

Ahmed, M., Ahmed, K., Khan, N., & Ahmed, R. (2007). Access to Education in Bangladesh Country Analytic Review of Primary and Secondary Education. Dhaka, Bangladesh: BRAC University Institute of Educational Development (BU-IED).

Ahmed, P. (2013). A flood of opportunity. RTNN. http://www.english.rtnn.net/newsdetail/detail/12/62/55046#.VipkZsl961s. Accessed 23 Oct 2015.

Alamgir, M. (2015). Students in areas miss schools due to lack of transport facilities, New Age. http://newagebd.net/165158/students-in%2D-areas-miss-schools-due-to-lack-of-transport-facilities. Accessed 12 Aug 2015.

Bacq, S., & Janssen, F. (2011). The multiple faces of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(5–6), 373–403.

Bose, S. (2013). Sea-level rise and population displacement in Bangladesh: Impact on India. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 9(2), 62–81.

BRAC (2016). Boat School. http://www.brac.net/education-programme/item/762-boat-school. Accessed 28 Dec 2016.

Chowdhury, A. M. R., & Bhuiya, A. (2004). The wider impacts of BRAC poverty alleviation programme in Bangladesh. Journal of International Development, 16(3), 369–386.

Chowdhury, A. M. R., Bhuiya, A., Chowdhury, M. E., Rasheed, S., Hussain, Z., & Chen, L. C. (2013). The Bangladesh paradox: Exceptional health achievement despite economic poverty. The Lancet, 382(9906), 1734–1745.

Chowdhury, S. S. (2015). Boat of Dreams, (The) Daily Star, http://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/boat-dreams-116341. Accessed 20 Dec 2015.

Chowdhury, W.S. (2005). How universal primary education in Bangladesh: A case study of the area. Population poverty and social development (PPSD). http://hdl.handle.net/2105/9204. Accessed 17 Dec 2015.

Clements, M. D., & Sense, A. J. (2010). Socially shaping supply chain integration through learning. International Journal of Technology Management, 51(10), 92–105.

Conrad, D. (2015). Education and social innovation: The youth uncensored project-a case study of youth participatory research and cultural democracy in action. Canadian Journal of Education, 38(1), 1–25.

Denscombe, M. (1998). The good research guide for small-scale social research projects. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Dhaka Tribune. (2013). Floating school educates haor children. http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/education/2013/09/20/floating-school-educates-haor-children/. Accessed 10 Apr 2014.

D'Ippolito, B., & Timpano, F. (2015). The role of non-technological innovations in services: The case of food retailing. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(1), 73–89.

Drucker, P. F. (1987). Social innovation – management’s new dimension. Long Range Planning, 20(6), 29–34.

Furco, A. (1996). ‘Service-Learning: A Balanced Approach to Experiential Education’, Service Learning, General, Paper 128, http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slceslgen/128. Accessed 10 Nov 2013.

Gryskiewicz, S. S., & Epstein, R. (2000). Cashing in on creativity at work. Psychology Today, 33(5), 62–67.

Guth, M. (2005). Innovation, social inclusion and coherent regional development: A new diamond for a socially inclusive innovation policy in regions. European Planning Studies, 13(2), 333–349.

Hargrave, T. J., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2006). A collective action model of institutional innovation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 864–888.

Hartley, J. F. (1994). Case studies in organizational research. In C. Casell & G. Symon (Eds.), Qualitative methods in organizational research: A practical guide (pp. 208–229). London: Sage Publications.

Heiskala, R., & Hämäläinen, T. J. (2007). Social innovation or hegemonic change? Rapid paradigm change in Finland in the 1980s and 1990s, Social innovations, institutional change and economic performance. Making sense of structural adjustment processes in industrial sectors, regions and societies, pp., 80–94.

Henderson, H. (1993). Social innovation and citizen movements. Futures, 25(3), 322–338.

Igarashi, Y., & Okada, M. (2015). Social innovation through a dementia project using innovation architecture. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 97, 193–204.

Kabeer, N., Mahmud, S., & Castro, J. G. (2012). NGOs and the political empowerment of poor people in rural Bangladesh: Cultivating the habits of democracy? World Development, 40(10), 2044–2062.

Lettice, F., & Parekh, M. (2010). The social innovation process: Themes, challenges and implications for practice. International Journal of Technology Management, 51(1), 139–158.

Loogma, K., Tafel-Viia, K., & Umarik, M. (2013). Conceptualizing educational changes: A social innovation approach. Journal of Education Change, 14(3), 283–301.

Marcy, R. T., & Mumford, M. D. (2007). Social innovation: Enhancing creative performance through causal analysis. Creativity Research Journal, 19(2–3), 123–140.

Martellucci, E. & Thum, A.E. (2013). Can Social Innovation in Schools Mitigate Educational Inequality? Lessons from Innovative Learning Environments and NEUJOBS.NEUJOBS Special Report, Milestone No. 9.

Master Plan of Area. (2012). Master Plan of Area, and wetland development board, Ministry of Water Resources. Bangladesh: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

Mulgan, G., Tucker, S., Ali, R., & Sanders, B. (2007). Social innovation: What it is, why it matters and how it can be accelerated. Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, Said Business School, Working Paper. Oxford: The Young Foundation, Oxford University.

Mumford, M. D. (2002). Social innovation: Ten cases from Benjamin Franklin. Creativity Research Journal, 14(2), 253–266.

Mumford, M. D., & Moertl, P. (2003). Cases of social innovation: Lessons from two innovations in the 20th century. Creativity Research Journal, 15(2–3), 261–266.

Nicholls, A. (2010). The legitimacy of social entrepreneurship: Reflexive isomorphism in a pre-paradigmatic field. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 611–633.

Nussbaumer, J., & Moulaert, F. (2004). Integrated area development and social innovation in European cities: A cultural focus. City, 8(2), 249–257.

OECD. (2000). LEED Forum on Social Innovations. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Forum-Social-Innovations.htm. Accessed 29 Nov 2016.

Phills, J. A., Deiglmeier, K., & Miller, D. T. (2008). Rediscovering social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6(4), 34–43.

Pol, E., & Ville, S. (2009). Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(6), 878–885.

Raju, M. N. A. (2013). Haor education: Should distance be the barrier? (The) Daily Star, http://archive.thedailystar.net/beta2/news/haor-education-should-distance-be-the-barrier. Accessed 29 Nov 2015.

Roy, P. (2015). Sorry tale of people in Bangladesh, (The) Daily Star, 15 October 2015.

Short, J. C., Moss, T. W., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2009). Research in social entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3(2), 161–194.

Simons, H. (1996). The paradox of case study. Cambridge Journal of Education, 26(2), 225–240.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 443–466). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

The Daily Star (2012). BRAC to build 400 boat schools by 2014. http://archive.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=257808. Accessed 24 Dec 2014.

The Daily Star (2015). Deal to improve lives of people in areas. http://www.thedailystar.net/deal-to-improve-lives-of-people-in-haor-areas-40509. Accessed 30 Mar 2015.

The World Bank. (2014). Education for All. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/brief/education-for-all. Accessed 24 Oct 2016.

Ümarik, M., Loogma, K., & Tafel-Viia, K. (2014). Restructuring vocational schools as social innovation? Journal of Educational Administration, 52(1), 97–115.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). United Nations: Universal Declaration of Human Rights. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights. Accessed 30 Dec 2015.

Vleva (2012). Report seminar 'extended schools’, Tuesday 14 February 2012.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage Publications.

Zaman, M. Q. (1991). Social structure and process in char land settlement in the Brahmaputra-Jamuna floodplain. Man, 26(4), 673–690.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the scholarship from the InterResearch, Bangladesh to carry out the research. The role of the funding body to support this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were part of manuscript preparation process and approved the final draft of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Jashim Uddin Ahmed, Ph.D. is a Professor of the Department of Management, School of Business & Economics, North South University, Bangladesh. He is also the founder of InterResearch, Dhaka, Bangladesh. He was awarded his Ph.D. in Management Sciences from The University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST), UK and he has achieved master degrees both in Marketing and Management from the University of Northumbria, UK. He also studied in the University of Reading and the University of Lincolnshire and Humberside, UK. His research interests are in the area of Higher Education, Strategic Management, and Contemporary Issues in Marketing and Management. Dr. Ahmed has published over 80 research articles and case studies in reputed journals. [Email: jashim.ahmed@northsouth.edu, jashimahmed@hotmail.com]

N. M. Ashikuzzaman graduated from North South University in 2015 with a Bachelor of Business Administration. He is a research associate with InterResearch, Dhaka, Bangladesh. [E-mail: n.m.ashikuzzaman786@gmail.com]

Aditi Sonia Mansur Mahmud graduated from University of Delhi in 1995 with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She later obtained a Masters in International Business from Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia. She has been teaching International Business courses at NSU since 2000. [E-mail: aditimahmud@hotmail.com]

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, J.U., Ashikuzzaman, N.M. & Mahmud, A.S.M. Social innovation in education: BRAC boat schools in Bangladesh. J Glob Entrepr Res 7, 20 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0077-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0077-z