Abstract

Cellulose nitrate (CN) has been used in the past as support for photographic negatives and cinematographic films. This material is particularly unstable and can undergoes severe degradation due to thermal, photocatalytic and hydrolytic loss of nitro groups from the lateral chain. Thus, to prevent the disappearance of the movies, their scanning and digitalization become a priority.

However, CN bases degradation may prevent the scanning of the films. The decrease in pH, for instance, lowers the viscosity of gelatin, which becomes softer. This causes the formation of gelatin residues which stick on the back of the superimposed frames inside the reels creating a deposit.

Traditional approaches to clean gelatin residues from the surface of CN bases include the mechanical removal with scalpels and the use of organic solvents (such as isopropyl alcohol). However, these methods are either slow and ineffective or could potentially damage the degraded CN supports.

To overcome these drawbacks, we have evaluated the performance of three choline chloride and betaine-based Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) formulations as alternative for the removal of gelatine residues from CN supports. These solvents are inexpensive (when compared to traditional solvents), easy to prepare, green (non volatile, safe towards the operators and the environment, and potentially recyclable), non flammable and have been previously proposed for the extraction of proteinaceous materials, but their use for the restoration of photographic negatives or cinematographic films has not been reported yet.

Selected areas over the frames of a real deteriorated CN cinematographic film were cleaned comparing the DES performances with the ones obtained using isopropyl alcohol as an example of a traditional method.

In particular, the tested DES formulations showed superior cleaning power compared to isopropyl alcohol and, at the selected application times, resulted capable to remove the gelatin residues without affecting the CN film supports.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The layout of early film materials (Fig. 1) include a thick, transparent and flexible cellulose nitrate (CN) base (c) coated with the film emulsion (a). The emulsion is the layer employed to record the image and, in already developed films, it consists of a colloidal suspension of dark silver particles and color dyes (if the film was colored) fixed in a matrix of photographic-grade gelatin [1]. Sometimes, a thin intermediate adhesive or “subbing” layer (b) was applied to guarantee the adhesion between the emulsion and the polymeric base.

Generic stratigraphy for a simple early-period CN film, showing the black and white (B&W) emulsion (a), in this case subjected to a red tinting process, an adhesive subbing layer (b) and the CN base (c). More complex films can include additional and thin layers such as an overcoat and an anti-curling layer, each one ≤ 1 µm thick, located over the emulsion, and below the base respectively

CN is a cellulose derivate where hydroxyl groups in the glucopyranose ring have been substituted by nitrate groups O-NO2.

Since 1889 [2, 3], flexible polymeric films made of CN with a degree of substitution (DS) of around 2 were used as support for the first examples of cinematographic film.

Thanks to its low cost, CN was initially widely employed for producing film bases, but due to its high flammability, its use of was progressively reduced and then definitely abandoned in 1951 [2, 3].

Cellulose nitrate photographic and cinematographic materials are known to be intrinsically unstable. The complex pathways of degradation of CN bases have been recently summarized by Neves et al. [4] and Berthumeyrie et al. [5]. Mainly, degradation starts with the thermal (Fig. 2), photocatalytic and hydrolytic loss of nitro substitutive groups of the CN base [6]. This process occurs quickly under uncontrolled storage conditions, particularly unventilated environments showing high temperature and humidity (temperature above 10 °C and a relative humidity above 50% [2, 7, 8]).

The resulting degradation product, the NO2 gases, react with environmental water producing nitric and nitrous acids, which catalyze further loss of nitro groups in the CN polymer and the reduction of the molecular weight of the backbone.

Eventually, the base deforms, becomes frail and brittle, and crumbles to dust [9]. To avoid the complete loss of the recorded images, their scanning and digitalization is a priority for cinematheques, libraries and other institutions safeguarding such audiovisual archives [10].

However, nitrate supports which have already underwent some degree of hydrolytic degradation of their bases can suffer from softening of their gelatin emulsions since the pH decreases to values lower than the isoelectric point of type B gelatin (which may vary from 4.7 to 5.6 [11,12,13,14], where the gelatin molecule becomes positively charged, and the repulsion forces between positive charges slightly uncoil the gelatin molecule and facilitate its solubilization [14]. Nguyen et al. have suggested also that acids derived by the generation of NO2 promote the hydrolysis of hardened (cross-linked) and unhardened photographic gelatins, lowering their molecular weight and their viscosity [15].

Photographic gelatin is produced from the alkaline treatment of demineralized cattle bone, ossein [9]. Ossein is mostly made up of type I collagen, an heterotrimer collagen formed by three polypeptide α-chains associated in a triple helix configuration [16]. By treating parent collagen with an hydrated lime slurry, type B gelatin is produced, destroying the crosslinking between collagen [12, 16,17,18].

Gelatin softening is a serious drawback, because upon becoming more fluid it can easily migrate laterally when it is pressured and adhere to any surface in contact with it. This often affects the back side of the subsequent coils of the same film (Fig. 3), causing the loss of images in the first coil and gelatin accumulation on the back of the second. The adhesion of convolutions, known as blocking, ultimately transforms the film into a solid unit which cannot be unrolled. At this stage the so called “hockey puck” state is reached as the film roll appears as a compact solid mass [9].

Therefore, to allow the digitalization of the film and to avoid subsequent blocking when the reel is stored, it becomes mandatory to remove gelatin accretions.

Traditional cleaning approaches to eliminate gelatin residues from the side of film rolls include mechanical removal with surgical scalpels, and the use of polar solvents, such as distilled water, ethanol (EtOH) and isopropyl alcohol (IPOH). However, the use of alcohols results in a slow, ineffective cleaning, whereas water may be potentially dangerous if it accidentally leaks towards the front of the frame when cleaning a section of the base. Furthermore, the use of organic solvents presents different drawbacks, since they are flammable, and the excessive emissions of volatile solvents can harm the environment and can pose health risks to the operator upon extended unprotected exposure. Considering that a movie may be hundred of meters in length several liters of solvents may be needed for its cleaning.

To overcome these drawbacks, we have proposed, tested and evaluated the performance of three deep eutectic solvent (DES) formulations, providing green (being safe, biodegradable [19] and potentially recyclable [20]), inexpensive (when compared to traditional solvents), easy-to-prepare and effective alternative for the cleaning of gelatin accretions from CN photographic bases.

DES have been previously employed for the dissolution of proteinaceous [21, 22] and other organic materials, but to the best of the authors’ knowledge have not been employed for the restoration of photographic negatives or cinematographic films. The DES produced by mixing choline chloride (ChCl) and urea (U), at the mole ratio 1:2 has been previously successfully applied in gel form to remove proteinaceous coatings in paintings [23].

Deep eutectic solvents, first defined by Abbot et al. in 2003 [24], are mixtures of a hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), commonly a quaternary ammonium salt, with an hydrogen bond donor (HBD), like an amide, amine, alcohol or carboxylic acid. Electrostatic charge delocalization (through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions) between these two constituents lower the fusion point or glass transition temperature below that of the original components when both are present near a certain molar ratio [25, 26].

The precursors, such as choline chloride (ChCl), betaine (B) and urea (U), are biodegradable, environmentally friendly (being obtained from renewable sources), relatively cheap and non-toxic.

Choline chloride is regarded as a B-complex vitamin and is extracted from biomass; betaine is the trimethyl derivative of glycine and is obtained as a metabolic oxidation product of choline in different organisms [27]. Betaine can be commercially retrieved by separation during sugar production from beets. Urea is the most commercialized nitrogenous fertilizer and is employed by mammals for processing nitrogen-containing compounds [28, 29].

Ethylene glycol (EG) is commonly exploited as antifreeze, wetting and plasticizer agent in industrial processes [30]. It has been extensively used to produce DES whose limited toxicity can be further decreased increasing water content [31]. By mixing choline chloride with ethylene glycol at a 1:2 molar proportion, a DES commonly called ethaline is obtained. This product has been widely studied due to its low viscosity and therefore high solubilizing power. Through computer modelling, it has been found that the HBD and HBA in this DES formulation form a supramolecular cage-like arrangement where the Cl− anion becomes the central element interacting with five hydroxyl groups, one from the choline cation and four from both EG molecules [32]. Ethaline has been reported as capable of extracting collagen peptides from cod skins without destroying the peptide bonds in the process and also of being able to solubilize singular alanine, glutamic acid, lysine, glycine and hydroxyproline amino acids without creating new chemical bonds with them, so the solubilization process is probably based on intermolecular hydrogen bond formation between Cl− and the amino and carboxyl groups [21].

When urea is used as HBD, it has been observed that relatively basic DES are obtained, owing to the presence of the amino group, and to the fact that a small fraction of ammonia is released through urea decomposition during DES preparation, rising the pH of the mixture [33].

The DES formed by mixing betaine and urea in a 1:2 ratio worked well for the extraction of bovine serum albumin protein, showing a low glass transition temperature. After FTIR studies, it was suggested that in this DES formulation not only hydrogen bonds but also Coulomb interactions are formed between HBD and HBA, so its intrinsic interactions and structure differ from those of choline chloride-based DES [34].

Experimental

Aim of study

The objective of this research is to test three green DES formulations; i.e., choline chloride: ethylene glycol, betaine: ethylene glycol, and betaine: urea; as cleaning agents for cinematographic film cleaning, comparing their performance with that of traditional methods based on IPOH and EtOH, employed as conventional solvents, and evaluating their impact on the cellulose nitrate support.

Materials

Reagents and solvents were acquired from (Sigma-Aldrich) and used without any further purification: Betaine ≥ 98%, choline chloride ≥ 98%, urea ACS reagent 99.0–100.5%, ethylene glycol anhydrous 99.5%, and distilled water were used as DES precursors (Fig. 4); 2-propanol (isopropyl alcohol) ACS reagent ≥ 99.8%, ethyl alcohol 96.0–97.2% were instead used as solvent.

An (Amersham Protran®) medical grade CN filter membrane with 0.45 µm pore size, was used as CN analytical reference.

Cinematographic film sample

Some coils of a CN 35 mm B&W positive print of the film My Little Baby (La Principessa), kindly donated by the Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna, were used for all testing. The emulsion showed an orange tinting treatment, and deterioration effects including emulsion softening and accretions. These softened gelatin residues accumulate on the back of the film base (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

DES preparation

The DES mixtures were prepared by mixing the HBA with a HBD at a 1:2 molar ratio. For those DES based on betaine, a small amount of distilled water (10 wt% for B:EG and 30% wt% for B:U) was added to keep their viscosity low enough at room temperature (see Table 1).

Mixing was performed in a petri dish by stirring vigorously at 70–75 °C until the components turned into a transparent fluid, then letting the glass dish stand still until the liquid cooled down.

Solubility tests

From the same degraded cinematographic film sample, eight rectangular pieces of similar size (approximately 6 mg each) were cut from areas which did not present residues of gelatin in the back. After the removal of the gelatin emulsion from the upper side with water the samples were dried for 2 days at room temperature.

The samples were weighed, their thickness measured with a Mutitoyo® MDC-25SX digimatic micrometer and their superficial appearance documented with Optical Microscopy (OM). This was done semi-quantitatively by following the same procedure used for evaluating the cleaning performance (see below): the color, topography, reflectiveness and detection of scratches was assessed by visual comparison of the bright and dark field photos taken in the same area before and after the treatment. The dimensions of areas showing changes in appearance were measured with the software ZEN 3.3 blue edition (©Carl Zeiss microscopy Gmbh).

The samples were subsequently subjected to solubility tests using the same solvents employed for the cleaning, to assess their impact on degraded CN. This was done by immersing the CN samples into 100 μl of each solvent and sonicating them in sealed vials for 10 min at room temperature. Two of the CN samples were immersed in ChCl:EG, two in B:EG, and two in B:U, whereas one was immersed in IPOH and another one in EtOH. Afterwards, samples were oven-dried for two days. The samples immersed in the DES formulation were rinsed for 1 min by immersion into 3 ml of IPOH and gently agitated before being put in contact with absorbing paper for removing eventual solvent residues, before allowing to dry for 2 days.

After drying, sample weights and thickness were measured again, and the film surface condition documented with OM to check the changes or damages created during the procedure.

Weighing of samples used in the solubility tests was performed with a (Discovery DV215CD Ohau Corporation®) analytical balance. Sample weight was measured 3 to 4 times, each thickness 2 times, and averaged values were employed for comparison.

To properly evaluate the effect on the CN base, each DES formulation was directly applied on areas without gelatin residues, according with the same procedures employed for the removal of gelatin residues described in the following paragraph, by using a small cotton swab (ctsw). The effects of the solvents on the CN base was evaluated analyzing before and after the treatments the surface and the cross sections of the base with OM and Micro-Attenuated Total-Internal Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (µATR-FTIR).

Cleaning procedure

A small ctsw soaked with pure ETOH, pure IPOH or the DES solvents was gently rolled over an area (ca. 0.7 × 0.7 cm) of the CN base surface, previously documented under OM and µATR-FTIR, using minimal mechanical strength. Application time was 3 min when cleaning with pure IPOH and ETOH, whereas DES were applied just for 1 min. The non-volatile DES residues were removed from the surface by rolling 2 cotton swabs soaked with IPOH for 1.5 min.

In total, 3 zones with comparable gelatin accretions were cleaned with each one of the 3 DES, one area was cleaned with pure IPOH, and another area was cleaned with pure ETOH, for a total of 11 areas.

Evaluation of the cleaning performance

The performance of the cleaning procedure was evaluated using OM under different lightning conditions and µATR-FTIR on the film surface before and after the treatment on all the 11 cleaning areas under investigation.

In particular, the presence of gelatin and DES residues, as well as morphological damages inflicted by the treatment on the CN base, were evaluated qualitatively by recording bright field (BF) and dark field (DF) surface microphotographs before and after the treatments. To semi-quantitatively assess the change of the superficial appearance of the samples, the extensions of areas with presence of residues or other changes were measured with the software ZEN 3.3. µATR-FTIR allowed to check the presence of characteristic DES and gelatin (amide II) bands. The extension and the thickness of collagen residues left over on the CN base were evaluated by OM observation of cross sections prepared before and after the treatment, measuring their length and thickness with the software ZEN 3.3.

Surface and cross section observation with optical microscopy using visible and UV lights

Surface and cross section photomicrographs have been recorded with an (Olympus DP70) cooled digital color camera directly connected to an (Olympus BX51M) Optical microscope with different magnification objectives (1.25–5 × for surface and 5–50 × for cross section photomicrographs) under visible and UV lights, respectively provided by a 100 W halogen projection lamp and an (Ushio Electric USH102D) lamp. Surface photos were taken with visible light under DF (to enable real color observation) and BF (to enhance surface topography changes, transparent residue detection, and side differentiation), whereas cross section photos were taken in visible light (to record real color appearance) and UV fluorescence (to enhance material and layer differentiation). Surface photomicrographs from each cleaned area and each solubility test sample were stitched together using ImageJ Grid-stitching plugin based on the method published by Preibisch et al. 2009 [35], using linear blending and maximum intensity blending modes to obtain a single image covering the whole area of interest.

Cross section preparation

Cross sections of the treated film areas were prepared for documentation with optical microscopy by embedding microsamples in KBr [36, 37]. To avoid the cracking of the pellet due to the thickness of the sample, we gently pressed manually the first half of the pellet (300 mg KBr), and after positioning the sample and adding the remaining 300 mg of KBr, the pellet was pressed at 2 tons for 1 min.

FTIR spectroscopy

All FTIR spectra were acquired using a (Thermo Scientific® Nicolet iN 10MX) spectrometer fitted with a mercury–cadmium–telluride (MCT) type A detector cooled by liquid nitrogen and a X–Y–Z motorized stage with 1 μm incremental steps. Transmission spectra of pure reagents for DES production were acquired in transmission mode using a (MidIR Agilent® Cary 630) using the same parameters. Spectra were recorded in the 4000 to 675 cm−1range, using a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1, applying 64 scans per measurement and 64 scans for the background, acquired before each measurement in air.

Characterization of surface materials and treatment evaluation were carried out using μATR-FTIR with a Ge ATR crystal and an optical aperture of 40 × 40 μm. The ATR crystal was cleaned with acetone after each measurements Reflection Absorption spectra of the DES mixtures were acquired on a thin DES layer over a gold-coated glass holder with an aperture of 80 × 80 μm.

FTIR spectra were recorded in air and automatically baseline corrected using (OMNIC™) Software (Thermo Electron Corporaton™) after blanking out the 2300–2400 cm−1 region, related to νCO2 signals.

μATR-FTIR measurements before cleaning were performed in 3 different spots of each of the 11 cleaning test areas, whereas μATR-FTIR analysis after cleaning was performed in 7 to 14 spots for each cleaning area to ensure the representativeness of the data. For the CN samples used in the solubility tests, three µATR-FTIR measurements were recorded using 150 × 150 optical aperture on each of the 8 dry samples at the same spots before and after the test.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the film sample

By a visual examination of the film it can be noted that the support appears slightly warped and fragile; the degraded emulsion from the front side has softened and it has adhered also to the back side of the film base.

A fragment of the film sample has been embedded to evaluate the thickness of the gelatin residues. As reported in Fig. 5, the CN base is about 124 μm-thick and is covered by a continuous layer of degraded gelatin with maximum thickness of 13 μm).

50 × UV OM cross-sections photomicrographs of the film taken in a degraded point, highlighting the average depth of each of its layers: the red-tinted emulsion residues (a, depth in white) adhered to the back side of the film base, the CN base (b, depth in red), and the original emulsion layer at the front of the film (c). The treated side of the CN base is looking up

μATR-FTIR measurements performed on the base (Fig. 6 table 2)present four strong absorption bands directly linked to the nitro group vibrations ascribable to cellulose nitrate (1640 cm−1, 1276 cm−1, 832 cm−1 and 750 cm−1) [38].

The band at 1728 cm−1 not present in the CN standard, is most likely related to the presence of camphor, commonly used as plasticizer for CN [38, 42], or to the presence of carbonyl intermediates (e.g. gluconolactones, gluconic and glucuronic acid) produced during scission of the CN chain at later degradation stages [6].

The broad band at 3426 cm−1 can be assigned to O–H stretching; the bathochromic shift of the band in comparison to the CN standard is a sign of the increase in hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups, following hydrolytic loss of nitrate groups as a consequence of degradation [44].

It can be noted that the signals ascribable to the CH groups between 2800 and 3000 cm−1 appears different in shape and relative intensity when comparing the film base with the CN standard. This may be due to the influence of the plasticizers and addictive added to the base.

The μATR-FTIR spectra registered on the orange-tinted emulsion residues over the CN base (Additional file 1: Figure S2) are quite similar to that of a gelatin glue standard. A shoulder at around 1727 cm−1 can be attributed to the C = O bond stretching, associated to camphor sublimating from the degrading film base or to plasticizers used in film emulsions themselves, such as oils [42, 45]. The peaks at 1340 and 825 cm−1 can be attributed to the presence of nitrates, which can be a residue of unreacted silver nitrate [46] or could derive from nitric and nitrous acids formed with the degradation of the CN base.

The strong characteristic band of amide II of gelatin at ca. 1539 cm−1 does not overlap with other CN or DES bands, so they were used to detect remaining glue residues after the cleaning treatments.

Characterization of the DES solvents

The DES solvents were characterized by recording FTIR spectra in reflectance-absorbance mode. Table 3 reports the DES diagnostic bands which do not overlap with CN and gelatin signals, so they have been used to verify the presence of DES residues after the cleaning. The assignments of the bands [30, 32, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53] are also reported (Table 3).

Solubility tests results and cleaning tests on the CN bases

The effects of DES formulations on the degraded CN base were evaluated by comparing the thicknesses, weights and superficial appearance of the samples before and after the solubility tests (see data reported in Additional file 1: Table S2). The same tests were performed also with ethanol (EtOH) and isopropyl alcohol (IPOH) which are commonly employed for movie restoration.

EtOH completely solubilized the CN sample while IPOH caused a 0.5% decrease from the sample initial weight, letting unchanged the sample appearance by visual observation.

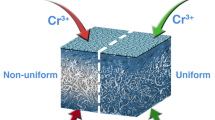

ChCl:EG clearly caused a change in the samples (see Additional file 1: Figure S3), which became whitish and decreased in transparency, showing evident softening of the plastic and a weight loss of 3.15%. This was expected at such long treatment times since previous researches showed the capability of ChCl:EG and other choline chloride-based DES to solubilize cellulose [54, 55].

B:EG induced a less pronounced whitish discoloration and loss of transparency, but no conclusive weight changes were observed on the samples. Finally, B:U seemed to have no effects on CN samples.

After observing the solubilization effects of each DES on fully immersed CN samples, cleaning tests with cotton swabs applied on the clean CN bases without gelatin just for 1 min were performed to evaluate their effect.

The surface OM photomicrographs (Additional file 1: Figure S4) show that after applying all three DES for this short application time, the treated areas did not have any distinctive changes on their surface: by qualitatively comparing the photos taken before and after the treatments, it is evident that no new scratches due to the cotton swab application, nor any loss of reflectivity can be detected.

The film depth variations measured by cross-section photos under UV light and the µATR-FTIR spectra (results not shown) indicated that the thickness of the films did not vary, and that no DES residues were found on the surface after the test. These findings suggests that the three formulations may be considered harmless towards the CN film supports when applied with cotton swabs with the proposed methodology.

Cleaning test results

The different treatments were applied to remove gelatin residues from the back side of the degraded movies described in section section “Characterization of the film sample”.

First, traditional cleaning systems (EtOH and IPOH) were tested and evaluated.

Comparing the OM surface photomicrographs before (Fig. 7I, Fig. 7 III) with the ones acquired after the treatments it can be noted that IPOH (Fig. 7II) did not remove the gelatin residues over the treated area, whereas EtOH (Fig. 7 IV) showed a better performance, but still abundant gelatin residues remained covering wide areas of the surface after the treatment. µATR-FTIR analyses and cross section photomicrographs (Fig. 7V–VIII) confirm that thick gelatin residues remain after both treatments, with thicknesses up to 13 and 6 µm respectively; presenting spectra acquired after cleaning which show a strong band at ca. 1539 cm−1, ascribable to the amide II vibration mode.

Evaluation of cleaning performance using traditional solvents. I–IV: dark field 5 × surface OM photomicrographs of selected film areas before (left) and after (right) being treated with IPOH (II) and EtOH (III) using the same methodology as used with the DES. V–VII: 50 × UV OM cross-section photomicrographs of the film before cleaning (left) and after cleaning with IPOH (center) and EtOH (right). The treated side of the CN base is looking up. VIII:µATR-FTIR spectra: representative spectrum of gelatin residues before cleaning (A, dashed line), a representative spectrum of the film surface once cleaned with IPOH (B, black), and EtOH (C, dark gray); spectrum of an unplasticized CN standard reference (D, light gray). Diagnostic amide II band due to gelatin presence is highlighted with a magenta diamond

In comparison, cleaning tests using all the three DES formulations showed a much more efficient cleaning efficacy.

From Fig. 8, we can observe that after the treatments the presence of gelatin residues was considerably and homogeneously reduced in all the treated surfaces. The documentation of the surface topography revealed that only a few, thin and well localized gelatin residues remained. There was no evident difference in cleaning efficiency among the three tested DES solvents with the method employed.

Accordingly, cross section analysis of samples collected after the treatment (Fig. 9) showed that after the treatments with all three DES, residues were few and drastically reduced in thickness, with average depths between 2 and 1 μm. Due to their transparency, thinness and number, these residues are not detectable with naked eye observation and remain hard to locate even at higher magnification. Therefore, it is less likely that they create a relevant impact during image scanning using transmitted light.

Interestingly, no damage was detected during OM surface documentation after any of the tests (Fig. 8), including scratches and gloss changes induced by mechanical action during cleaning.

Cross section photomicrographs (Fig. 9) also proved that after treatment, the CN base did not show detectable thickness changes, with minor differences being likely due to intrinsic base depth variability.

The vast majority of the µFTIR-ATR spectra acquired on each cleaned area (Fig. 10) did not show the bands associated to gelatin and the ones related to the DES solvents, confirming that the treatment not only resulted effective in removing the gelatin, but also left no major solvent residues. In particular, solvent residues were less frequently detected on the areas treated with ChCl:EG.

FTIR spectra. Each figure shows: µATR-FTIR of the gelatin residues covering each area before cleaning (A, dashed line), a representative µATR of the film surface once cleaned (B, black), µATR-FTIR of an unplasticized CN standard (C, dark gray) and the reference RAS-FTIR of each DES employed (D, light gray: I. ChCl:EG; II. B:EG; III. B:U). Diagnostic FTIR bands due to the CN base and its plasticizer are accompanied with a blue circle; the one due to gelatin presence shows a magenta diamond, and the peaks attributable to DES presence are highlighted with green triangles

All remaining DES/gelatin residues were punctual and very constrained spatially over the cleaned surface. Most were transparent, and all had diameters of less than 0.39 mm.

Overall, all three DES showed good cleaning action, with equivalent efficiency for the removal of gelatin when applied by cotton swab. None of these solvents created damage to the CN base. In particular, ChCl:EG showed lower viscosity than the other two DES, which increased control over the area of application and facilitated the monitoring of the cleaning level during the treatment, whereas the more viscous betaine-based DES tended to obscure the surface during treatment and made it difficult to assess the cleaning level until removal with IPOH. Moreover, ChCl:EG seemed to be more easily removed after the treatment by application of an IPOH-soaked cotton swab.

Conclusion

All the three formulations proved to be efficient in the removal of photographic gelatin residues from cinematographic CN bases using cotton swabs for application, so they are suitable for restoration purposes when followed by IPOH application for removal of DES residues. At short application times in the order of one minute, DES seem innocuous towards polymeric film bases as the cleaning tests on the clean CN bases suggested. IPOH was employed with a limited application time just for the removal of the DES residues. The alcohol appears ineffective when employed for the removal of the gelatin residues with short application time. Since this is the solvent normally employed for this type of treatment it means that larger amount with higher application times should be employed to have satisfactory cleaning results. This suggest that the proposed method allowed to reduce both the amount and the exposure to IPOH which is a flammable substance.

In conclusion, DES solvents seem particularly promising for the treatment of degraded CN film bases, and for separating glued cinematographic and photographic material before they arrive to the hockey puck state.

Further research is ongoing to test the applicability of these new solvents through the use of carrying semirigid absorbing materials, to remove the mechanical action of the cotton swab.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- B:

-

Betaine

- ChCl:

-

Choline chloride

- CN:

-

Cellulose nitrate

- DES:

-

Deep eutectic solvents

- EtOH:

-

Ethanol

- EG:

-

Ethylene glycol

- IPOH:

-

Isopropyl alcohol

- OM:

-

Optical microscopy

- µATR-FTIR:

-

Micro-attenuated total reflectance fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- B&W:

-

Black and white

- DS:

-

Degree of substitution

- HBA:

-

Hydrogen bond acceptor

- HBD:

-

Hydrogen bond donor

- Ctsw:

-

Cotton swab

- BF:

-

Bright field

- DF:

-

Dark field

- MCT:

-

Mercury–cadmium–telluride

References

Read P, Meyer MP. Restoration of motion picture film. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2000. 359 p. (Butterworth-Heinemann series in conservation and museology).

Bereijo A. The conservation and preservation of film and magnetic materials (1): film materials. Libr Rev. 2004;53(6):323–31.

Edward Chauncey Worden. Nitrocellulose Industry. 1911. http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.163826. Accessed 24 Apr 2020.

Neves A, Ramos AM, Callapez ME, Friedel R, Réfrégiers M, Thoury M, et al. Novel markers to early detect degradation on cellulose nitrate-based heritage at the submicrometer level using synchrotron UV–VIS multispectral luminescence. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20208.

Berthumeyrie S, Collin S, Bussiere PO, Therias S. Photooxidation of cellulose nitrate: new insights into degradation mechanisms. J Hazard Mater. 2014;15(272):137–47.

Nunes S, Ramacciotti F, Neves A, Angelin EM, Ramos AM, Roldão É, et al. A diagnostic tool for assessing the conservation condition of cellulose nitrate and acetate in heritage collections: quantifying the degree of substitution by infrared spectroscopy. Herit Sci. 2020;8(1):33.

Lavédrine B, Gandolfo JP, Frizot M, Monod S. Photographs of the past: process and preservation. Los Angeles: Getty Publications; 2009. p. 367.

Lavédrine B, Lavédrine J, Lavédrine P, Gandolfo JP, Monod S. A guide to the preventive conservation of photograph collections. Los Angles: Getty Publications; 2003. p. 304.

FilmCare.org. https://www.filmcare.org/vd_binder.php. Accessed 30 Apr 2021.

Catelli E, Sciutto G, Prati S, Chavez Lozano MV, Gatti L, Lugli F, et al. A new miniaturised short-wave infrared (SWIR) spectrometer for on-site cultural heritage investigations. Talanta. 2020;218:121112.

Schrieber R, Gareis H. Gelatine handbook: theory and industrial practice. 1st ed. Wiley; 2007. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9783527610969. Accessed 30 Mar 2021.

Johnston FA. Gelatine. In: Harris P, editor. Food Gels. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands; 1990.

Mees CEK, James TH, Kocher A, Berry CR. The theory of the photographic process. 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan; 1966. 591 p. https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/12386604. Accessed 9 Jan 2019.

Haist GM. Modern photographic processing. New Jersy: Wiley; 1979.

Nguyen TP, Lavédrine B, Flieder F. Effects of N02 and S02 on the degradation of photographic gelatin. Imaging Sci J. 1997;45(3–4):239–43.

Bella J. Collagen structure: new tricks from a very old dog. Biochem J. 2016;473(8):1001–25.

Balakhnina IA, Brandt NN, Mankova AA, Chikishe Yu A. The problem of manifestation of tertiary structure in the vibrational spectra of proteins. Vib Spectrosc. 2021;114:3250.

Derkach SR, Kuchina YA, Baryshnikov AV, Kolotova DS, Voronko NG. Tailoring cod gelatin structure and physical properties with acid and alkaline extraction. Polymers. 2019;11(10):1724.

Juneidi I, Hayyan M, Hashim MA. Evaluation of toxicity and biodegradability for cholinium-based deep eutectic solvents. RSC Adv. 2015;5(102):83636–47.

Clarke CJ, Tu WC, Levers O, Bröhl A, Hallett JP. Green and sustainable solvents in chemical processes. Chem Rev. 2018;118(2):747–800.

Bai C, Wei Q, Ren X. Selective extraction of collagen peptides with high purity from cod skins by deep eutectic solvents. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2017;5(8):7220–7.

Li N, Wang Y, Xu K, Huang Y, Wen Q, Ding X. Development of green betaine-based deep eutectic solvent aqueous two-phase system for the extraction of protein. Talanta. 2016;152:23–32.

Jia Y, Sciutto G, Botteon A, Conti C, Focarete ML, Gualandi C, et al. Deep eutectic solvent and agar: a new green gel to remove proteinaceous-based varnishes from paintings. J Cult Herit. 2021;1(51):138–44.

Abbott AP, Capper G, Davies DL, Rasheed RK, Tambyrajah V. Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures. Chem Commun. 2003;1:70–1.

Li W, Zhang Z, Han B, Hu S, Song J, Xie Y, et al. Switching the basicity of ionic liquids by CO2. Green Chem. 2008;10(11):1142–5.

Smith EL, Abbott AP, Ryder KS. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) and their applications. Chem Rev. 2014;114(21):11060–82.

Lin JC, Gant N. Chapter 2.3—The biochemistry of choline. In: Stagg C, Rothman D, editors. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy. San Diego: Academic Press; 2014. p. 104–10. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124016880000082. Accessed 9 Nov 2021.

Francisco M, van den Bruinhorst A, Kroon MC. Low-transition-temperature mixtures (LTTMs): a new generation of designer solvents. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(11):3074–85.

Zahrina I, Nasikin M, Mulia K. Evaluation of the interaction between molecules during betaine monohydrate-organic acid deep eutectic mixture formation. J Mol Liq. 2017;1(225):446–50.

Guo YC, Cai C, Zhang YH. Observation of conformational changes in ethylene glycol–water complexes by FTIR–ATR spectroscopy and computational studies. AIP Adv. 2018;8(5):055308.

Rodrigues LA, Cardeira M, Leonardo IC, Gaspar FB, Radojčić RI, Duarte ARC, Paiva A. Matias AA deep eutectic systems from betaine and polyols—physicochemical and toxicological properties. J Mol Liq. 2021;335:116201.

Wagle DV, Deakyne CA, Baker GA. Quantum chemical insight into the interactions and thermodynamics present in choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120(27):6739–46.

Simeonov SP, Afonso CAM. Basicity and stability of urea deep eutectic mixtures. RSC Adv. 2016;6(7):5485–90.

Zeng CX, Qi SJ, Xin RP, Yang B, Wang YH. Synergistic behavior of betaine–urea mixture: formation of deep eutectic solvent. J Mol Liq. 2016;219:74–8.

Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1463–5.

Prati S, Sciutto G, Bonacini I, Mazzeo R. New frontiers in application of FTIR microscopy for characterization of cultural heritage materials. Top Curr Chem. 2016;374(3):26.

Mazzeo R, Joseph E, Prati S, Millemaggi A. Attenuated total reflection-fourier transform infrared microspectroscopic mapping for the characterisation of paint cross-sections. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;599(1):107–17.

Quye A, Littlejohn D, Pethrick RA, Stewart RA. Investigation of inherent degradation in cellulose nitrate museum artefacts. Polym Degrad Stab. 2011;96(7):1369–76.

Mitchell G, France F, Nordon A, Tang P, Gibson LT. Assessment of historical polymers using attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infra-red spectroscopy with principal component analysis. Herit Sci. 2013;1(1):28.

Moore DS, McGrane SD. Comparative infrared and Raman spectroscopy of energetic polymers. J Mol Struct. 2003;661–662:561–6.

Pereira A, Candeias A, Cardoso A, Rodrigues D, Vandenabeele P, Caldeira AT. Non-invasive methodology for the identification of plastic pieces in museum environment—a novel approach. Microchem J. 2016;124:846–55.

Izzo FC, Carrieri A, Bartolozzi G, Keulen H van, Lorenzon I, Balliana E, et al. Elucidating the composition and the state of conservation of nitrocellulose-based animation cells by means of non-invasive and micro-destructive techniques. J Cult Herit. 2018; https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1296207418301134. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

Edge M, Allen NS, Hayes M, Riley PNK, Horie CV, Luc-Gardette J. Mechanisms of deterioration in cellulose nitrate base archival cinematograph film. Eur Polym J. 1990;26(6):623–30.

Kovalenko VI, Mukhamadeeva RM, Maklakova LN, Gustova NG. Interpretation of the IR spectrum and structure of cellulose nitrate. J Struct Chem. 1994;34(4):540–7.

Noohi S, Asadian H. Application of FTIR microscopy to identify some glass plates of golestan palace photo archive. Nian Conserv Sci J. 2017;01(01):48–53.

Miller FA, Wilkins CH. Infrared spectra and characteristic frequencies of inorganic ions. Anal Chem. 1952;24(8):1253–94.

Viertorinne M, Valkonen J, Pitkänen I, Mathlouthi M, Nurmi J. Crystal and molecular structure of anhydrous betaine, (CH3)3NCH2CO2. J Mol Struct. 1999;477(1):23–9.

Biernacki K, Souza HKS, Almeida CMR, Magalhães AL, Gonçalves MP. Physicochemical properties of choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents with polyols: an experimental and theoretical investigation. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(50):18712–28.

Du C, Zhao B, Chen XB, Birbilis N, Yang H. Effect of water presence on choline chloride-2urea ionic liquid and coating platings from the hydrated ionic liquid. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):29225.

Baran J, Barnes AJ, Engelen B, Panthöfer M, Pietraszko A, Ratajczak H, et al. Structure and polarised IR and Raman spectra of the solid complex betaine–trichloroacetic acid. J Mol Struct. 2000;5(550–551):21–41.

Grdadolnik J, Maréchal Y. Urea and urea–water solutions—an infrared study. J Mol Struct. 2002;615(1–3):177–89.

Ilczyszyn MM, Ratajczak H. Polarized vibrational spectra of betaine monohydrate single crystal. Vib Spectrosc. 1996;10(2):177–89.

Krishnan K, Krishnan RS. Raman and infrared spectra of ethylene glycol. Proc Indian Acad Sci. 1966;64(2):111.

Häkkinen R, Abbott A. Solvation of carbohydrates in five choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents and the implication for cellulose solubility. Green Chem. 2019;21(17):4673–82.

Zdanowicz M, Wilpiszewska K, Spychaj T. Deep eutectic solvents for polysaccharides processing. Rev Carbohydr Polym. 2018;200:361–80.

Acknowledgements

We heartily thank the Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and the specialists from L’Immagine Ritrovata S.r.l. (Marianna de Sanctis, Maura Psichedda and Lara Nobili) for supporting the research, for providing the studied samples and for providing access their facilities for the necessary testing.

Funding

This work was supported by the Emilia-Romagna Region [European Social Fund Scholarship for PhD Research Projects; 2014/2020 program. Project title: RICORDACI-Ricerca sulla conservazione, restauro e diagnosi di film cinematografici, approved DGR 886/2016]. The funding body had no incidence on the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MVCL: designed and performed the research, curated, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the original draft. SP: contributed to design the research; reviewed, edited, and provided validation for the work. GS: contributed to design the research, reviewed and edited the work. RM: reviewed the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Detail of the film appearance. Figure S2. µATR-FTIR spectra of industrial bovine glue reference (A, dashed line) and of the gelatin residues found over the studied sample (B, black). The diagnostic FTIR band due to gelatin presence is highlighted with a magenta diamond. Figure S3. Bright Field surface OM photomicrographs of CN base samples areas before (left) and after (right) being subjected to solubility tests inChCl:EG (I), B:EG (II) and B:U (III). Figure S4. Bright Field surface OM photomicrographs of relatively clean film base areas before (left) and after (right) being treated with ChCl:EG (I), B:EG (II) and B:U (III) using the same methodology for removal of gelatin residues. It can be notice that dark circular scratches due to cotton swab application. Are absent White lines instead reflect cracks in the gelatin emulsion at the other side of the film base, due to pressure applied by cotton swab treatment. Table S1. Assignments of the main infrared absorption bands of the spectra in Figure S2 ( assignments are based on the bibliography 1-5 reported in the SM). Table S2. Averaged values of weight, thickness and DS measured of the studied CN base before and after being subjected to solubility tests with the four solvents employed for cleaning.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lozano, M.V.C., Sciutto, G., Prati, S. et al. Deep eutectic solvents: green solvents for the removal of degraded gelatin on cellulose nitrate cinematographic films. Herit Sci 10, 114 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00748-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00748-9