Abstract

Background

Emotion dysregulation (ED) is a core intrinsic feature of adult presenting Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). However, the clinical expressions of ED are diverse and several questionnaires have been used to measure ED in adults with ADHD. Thus, to date, the characteristics of ED in adult ADHD remain poorly defined. The objective of this study is to identify the different patterns of ED in adults with ADHD.

Methods

A large sample of 460 newly diagnosed adults with ADHD were recruited. Patients completed a total of 20 self-reported questionnaires. Measures consisted in the several facets of ED, but also other clinical features of adult ADHD such as racing thoughts. A factor analysis with the principal component extraction method was performed to define the symptomatic clusters. A mono-dimensional clustering was then conducted to assess whether participants presented or not with each symptomatic cluster.

Results

The factor analysis yielded a 5 factor-solution, including “emotional instability”, “impulsivity”, “overactivation”, “inattention/disorganization” and “sleep problems”. ED was part of two out of five clusters and concerned 67.52% of our sample. Among those patients, the combined ADHD presentation was the most prevalent. Emotional instability and impulsivity were significantly predicted by childhood maltreatment. The ED and the “sleep problems” factors contributed significantly to the patients’ functional impairment.

Conclusions

ED in ADHD is characterized along emotional instability and emotional impulsivity, and significantly contributes to functional impairment. However, beyond impairing symptoms, adult ADHD may also be characterized by functional strengths such as creativity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder, concerning 4% of the adult population [1,2,3]. ADHD involves difficulties in managing attention resources, motor restlessness and impulsive behaviors leading to major functional difficulties [4,5,6]. Three clinical pictures of ADHD have been classically described. The predominantly inattentive presentation concerns patients who meet difficulties in sustaining their attention, and present with distractibility and disorganization. The predominantly hyperactive presentation refers to patients who deal with motor restlessness, excessive talkativeness and difficulties in waiting their turn. The combined presentation corresponds to a combination of the forementioned symptoms [4]. However, when applied strictly, these criteria often lead to false negatives and underdiagnosis of ADHD in adults [7]. In fact, the clinical picture of ADHD in adults is not a perfect continuation of the ADHD symptomatology found in children. Indeed, in adults, attention deficits often increase, while motor hyperactivity tends to be internalized [7,8,9,10,11]. Thereby, many studies have suggested that adult ADHD should be considered beyond the classical triad of symptoms reported in children. For instance, based on patients’ reports, Asherson [12] described a specific clinical picture found in adults with ADHD, including inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, but also mental restlessness, sleep difficulties and, most importantly, emotion dysregulation (ED; [12, 13]). ED is characterized by the experience and expression of excessive emotions along with rapid and exaggerated swings in emotional states [14]. ED can be conceptualized as a dimensional construct as individuals differ in terms of both the number and the severity of ED symptoms (e.g. emotional lability, irritability, low frustration tolerance;14). From this perspective, given that ED is found in different psychiatric diagnoses, ED is usually considered as a transdiagnostic feature [15,16,17]. For instance, high levels of ED are found in Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), but also in mood disorders, anxiety disorders and substance use disorders [17,18,19,20,21].

Since the first descriptions of adults with ADHD, emotional difficulties have been considered as a main symptom of the disorder in adults. For instance, Wender et al. [22] considered ED among the core symptoms of adult ADHD. This has been confirmed by several recent studies [23,24,25,26]. Indeed, ED is experienced by up to 70% of adults with ADHD [14, 27,28,29] and is highly associated with the core ADHD symptoms [30,31,32,33,34]. For instance, ED is particularly associated with hyperactivity [35], but also to additional symptoms typically found in adults with ADHD, i.e., racing thoughts and sleep difficulties [36]. Importantly, compared to the classic triad of symptoms, ED has been found to contribute significantly more to functional impairment in adults with ADHD [14, 24, 34, 37,38,39].

Regarding the etiology of ED in ADHD, it has been demonstrated that ED is not due to a comorbid disorder, but it is rather intrinsic to ADHD [34, 40,41,42,43]. However, little is known about the factors contributing to the development of ED in ADHD. To date, the genetic hypothesis is the most studied, considering that ADHD and ED are highly heritable [44,45,46,47]. Furthermore, family studies highlighted that the first-degree relatives of people presenting with both ADHD and ED are more likely to present with emotional difficulties than the first-degree relatives of individuals presenting with ADHD without ED [48,49,50]. However, some environmental factors might also be involved, such as childhood maltreatment. Indeed, compared to non-clinical controls, adults with ADHD report a greater number of traumatic events during childhood [51]. Conversely, maltreated children often present with ADHD [52, 53]. In a recent study led by Rüfenacht et al. [54], self-reported emotional neglect and abuse during childhood were found to contribute to emotional reactivity and poor emotion regulation strategies in adult ADHD.

Although ED is not considered to be disorder-specific, BPD is typically seen as the “gold-standard” presentation of ED. BPD is a highly impairing mental disorder characterized by a persistent pattern of unstable relationships associated with pronounced impulsive and self-harming behaviors, unstable identity and difficulties regulating emotions [4]. More specifically, ED in BPD is defined by affective instability, uncontrolled anger, and impulsive self-harming behaviors [55,56,57,58]. This clinical description of ED in BPD has been confirmed by studies using experience sampling assessments of emotional symptoms. In these studies, adults presenting with BPD have been found to experience more intense negative emotions, but also a greater instability of both positive and negative emotions compared to healthy peers [59,60,61]. Moreover, from a dynamic standpoint, adults with BPD experience emotional over-reactivity combined with a slower return to a neutral emotional state [62]. In adults with ADHD, a similar expression of ED (i.e. increased intensity and instability of negative emotions) has been reported in a number of studies [14, 41, 57, 63,64,65,66]. In particular, adults with ADHD present high levels of irritability, temper outbursts [41, 67], emotional lability (i.e. shifts from a neutral state to depressed mood or mild excitement; [12, 33, 34, 57, 67, 68]) and emotional over-reactivity (vulnerability to stressful situations, rapidly overwhelmed; [12, 33, 68]). However, compared to adults with ADHD, people with BPD experience reduced intensity of happiness [57].

Although the presence of ED in adults with ADHD is now established, the clinical characteristics of ED in ADHD remain poorly defined. Indeed, according to the instruments used in different studies, ED in ADHD has been characterized as “irritability” [41, 67], “lability and exacerbated emotional intensity” [24, 33, 34], but also “cyclothymia” [69, 70], and “borderline personality traits” [71]. Cyclothymic temperament is the most prevalent affective temperament in adults with ADHD [69, 70, 72, 73] and typical borderline symptoms are common in adults with ADHD [71]. However, it is unclear whether and how these aspects are related to ED in adults with ADHD. For example, some patients appear to have borderline personality traits [74], while others exhibit a cyclothymic temperament [69], suggesting that different patterns of ED could be observed. The aim of this study is to identify the clinical patterns of ED in adults with ADHD. To this end, a large cohort of newly diagnosed adults with ADHD completed self-reported questionnaires investigating several facets of ED symptoms. We also investigated ADHD symptoms more broadly, including clinical dimensions usually associated with ADHD (e.g., sleep difficulties and racing thoughts), and how ED features were associated with childhood maltreatment and functional impairment.

Methods

Participants

A total of 460 adults newly diagnosed with ADHD aged 18 to 76 (M = 33.89 years; SD = 10.76, 52.6% were women) were included in this cross-sectional study. Participants were recruited from the outpatient psychiatry clinics of the University Hospital of Strasbourg. Clinical assessments were led by senior psychiatrists and diagnoses were established according to the DSM-5 criteria for ADHD and comorbidities [4]. Inclusion criteria included being older than 18 years and the absence of a current acute depressive or manic phase. Demographic data, comorbidities and treatment were recorded at the diagnostic assessment. After the clinical interview, all patients completed several self-reported questionnaires assessing ADHD, other psychiatric disorders’ symptoms (e.g., borderline, depressive and anxiety symptoms) and additional clinical dimensions including ED questionnaires. We excluded subjects with missing data, thus the analyses were conducted on a sample of 391 adults with ADHD.

Subjects provided a written consent prior to inclusion in the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculties of Medicine, Odontology, Pharmacy, Schools of Nursing, Physiotherapy, Maieutics and the University Hospitals of Strasbourg.

Questionnaires

The Self-Reported Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (SR-WRAADDS; [75]) is a 61-item self-reported questionnaire assessing ADHD symptomatology, including inattention, hyperactivity, disorganization and emotional dysregulation (the 30 first items), and its impact on patients’ daily life (the 31 last items). A recent factor analysis conducted on the 30 items measuring ADHD-related symptoms in a sample of adults with ADHD yielded a four-factor model, encompassing: (i) attention/disorganization (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 21, 22, 23, 24), (ii) hyperactivity/restlessness (items 7, 8, 9), (iii) impulsivity/emotional outbursts (items 10, 11, 12, 26, 29), (iv) emotional lability (items 13, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20) [26]. In this study, we only focus on the ADHD symptomatology and chose to use this new factor solution.

Impulsivity was assessed according to the five-factor model of impulsivity using the Urgency Premeditation Perseverance Sensation seeking-Positive urgency short version (UPPS-P; [76]). The UPPS-P is a 20-item scale comprising 4 items per impulsive dimension (i.e. “Urgency”, “Positive urgency”, “Lack of premeditation”, “Lack of perseverance”, “Sensation seeking”). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“totally agree”) to 4 (“totally disagree”).

The Borderline Symptom List-23 (BSL-23; [77]) is a self-reported questionnaires assessing the severity of the typical borderline symptomatology. The BSL-23 comprises 23 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very strong”). A total score is calculated including all the 23 items.

Depression symptoms were assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; [78, 79]). The BDI is a 21-item self-reported questionnaire with items ranging from 0 (the symptom is absent) to 3 (maximum severity).

The brief Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego Autoquestionnaire (TEMPS-A; [80]) is the short version of the 110-item original questionnaire comprising 39 items, rated on a yes-or-no scale. The TEMPS-A is a self-reported questionnaire designed to assess affective temperaments via five subscales: (i) items 1 to 12 assess cyclothymic temperament, (ii) items 13 to 20 assess depressive temperament, (iii) items 21 to 28 assess irritable temperament, (iv) items 29 to 36 assess hyperthymic temperament, and (v) items 37 to 39 assess anxious temperament. To enhance response variability, the original TEMPS-A scale underwent adaptation. Each item was transformed into a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ("not at all") to 3 ("a lot"), as opposed to the binary response format of a yes-or-no scale. This modification has broadened the range of responses.

The Racing and Crowded Thoughts Questionnaire-13-item (RCTQ-13; [81]) is a 13-item self-reported questionnaire assessing three facets of racing thoughts during the last 24 h – i.e., thought overactivation, burden of thought overactivation and thought overexcitability. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“totally agree”).

The Cognitive Processes Associated with Creativity (CPAC; [82]) is a 28-item self-reported questionnaire measuring the use of different cognitive strategies involved in the creative process. The CPAC encompasses 5 subscales i.e., idea manipulation, imagery, flow of ideas, metaphorical/analogical thinking, idea generation and idea incubation. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”).

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI, [83]) is a 7-item self-reported questionnaire assessing insomnia symptoms, including type, severity and functional impact. Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”).

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS; [84]) is a 8-item self-reported questionnaire assessing the propensity to be sleepy in 8 different daily situations (e.g. when watching TV, when reading a document, when having a conversation…). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“weak probability”) to 3 (“high probability”).

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short-form (CTQ-SF; [85]) was used to assess the different childhood maltreatment (e.g. sexual abuse, emotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical abuse and physical neglect) that might be involved in the severity of ADHD symptomatology. The CTQ-SF is a self-reported questionnaire comprising 28 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“very often”).

The Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale (WFIRS; [86, 87]), is a 69-item self-reported questionnaire used to assess functional impairment. The WFIRS assesses daily difficulties in ADHD in seven domains of functioning (family, work, school, life skills, self-concept, social functioning, and risky activities). Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“never”) to 3 (“very often”).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages of categorical variables together with means and standard deviations of continuous variables. To investigate the different possible symptoms clusters in our sample of adults with ADHD, a factor analysis with the principal component extraction method was performed [88]. Considering that the obtained factors were correlated, an oblique rotation (Oblimin) was applied. Factors were retained based on their eigenvalue (greater than 1) and after inspection of the scree plot. Only non-overlapping items with loadings greater than 0.40 were considered as being part of a factor. A mono-dimensional clustering was conducted for each principal component obtained to assess whether participants presented or not with each symptomatic factor [89]. This mono-dimensional clustering consisted in an unsupervised k-means clustering for which we predetermined 2 clusters. Following the analysis, a score of 0 was attributed to the cluster when the patient did not present with this specific symptoms whereas a score of 1 was attributed when the patient was concerned by the symptomatic cluster. The mono-dimensional clustering was based on each subject factor score for each of the 5 components calculated by the Jamovi® software.. Finally, two linear regression analyses were conducted. On the one hand, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed to investigate the contribution of the identified factors in functional impairment. On the other hand, a simple linear regression analysis was carried out to partial out the specific contribution of childhood maltreatment on the extracted symptomatic factors. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. Analyses were performed using the Jamovi® and MatLab® softwares.

Results

Demographic description

Among the 391 retained adults with ADHD, the combined presentation was the most prevalent, concerning 73.40% of the group, followed by the inattentive presentation and the hyperactive one (22.9% and 3.7% respectively). Regarding psychiatric comorbidities, 34.1% (n = 106) experienced a past episode of depression and 15.1% (n = 41) have a comorbid bipolar disorder. 14.8% (n = 16) adults of our sample had an anxiety disorder, 2.05% (n = 8) presented with an obsessive–compulsive disorder, 8% (n = 40) presented a borderline personality disorder and 4.5% (n = 14) an autism spectrum disorder. Concerning medications, 67% (n = 154) of patients did not take any psychotropic drugs at the time of the recruitment. Among those under medication at recruitment, 1.28% (n = 5) had just started their psychostimulant treatment, 18.4% (n = 52) were treated with antidepressants and 10.3% (n = 29) with anxiolytics. Moreover, 9.90% (n = 28) of the sample were taking mood stabilizers, 7.1% (n = 20) antipsychotics and 2.8% (n = 8) were under hypnotics. Detailed demographic data are presented in Table 1.

Factor analysis

A total of 20 variables were used to perform the factor analysis. The variables consisted in the four symptoms subscales of the SR-WRAADDS (i.e., attention/disorganization, hyperactivity/restlessness, impulsivity/emotional outbursts and emotional lability), the five UPPS-P subscales, the BSL-23, the BDI, the five TEMPS-A subscales, the RCTQ-13, the CPAC, the ISI and the ESS. The analysis yielded a five factors solution explaining 60.1% of the total variance. Each factor presented with an eigenvalue greater than 1 (eigenvalues 5.52, 2.09, 1.87, 1.39, 1.15 respectively), explaining 17.1%, 15.6%, 11.1%, 8.9% and 7.4% of the variance (Table 2). The first factor, labelled “emotional instability”, had strong factor loadings for the TEMPS-A-Depressive subscale, the BDI, the BSL-23, the SR-WRAADDS-Emotional lability subscale, the TEMPS-A-Cyclothymic subscale and the TEMPS-A-Anxious subscale. The second factor, “impulsivity” included the UPPS-P-Urgency subscale, the SR-WRAADDS-Impulsivity subscale, the UPPS-P-Positive urgency subscale, the UPPS-P-Lack of premeditation subscale and the TEMPS-A-Irritable subscale. The third factor, labelled “overactivation”, comprised the CPAC, the TEMPS-A-Hyperthymic subscale, the RCTQ-13 and the SR-WRAADDS-Hyperactivity subscale. The fourth factor, labelled “inattention/disorganization”, had strong factor loadings for the UPPS-P-Lack of perseverance subscale and the SR-WRAADDS-Attention/Disorganization subscale. The fifth factor, labelled “sleep problems”, consisted in the ISI and the ESE. The UPPS-P-Sensation seeking subscale was not considered because of its overlap between the “impulsivity” and the “overactivation” factors.

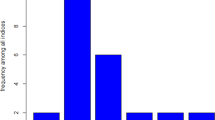

Mono-dimensional clustering

In total, 218 subjects presented the “emotional instability” cluster, 197 the “impulsivity” cluster, 234 the “overactivation” cluster, 240 the “inattention/disorganization” cluster and 199 the “sleep problems” cluster (Fig. 1). On the whole sample, only few patients presented with only one symptomatic cluster. 4, 3, 14, 26 and 15 participants respectively presented with just “emotional instability”, “impulsivity”, “overactivation”, “inattention/disorganization” or “sleep problems”. In most cases, adults with ADHD were attributed to several clusters (n = 300), whereas some patients do not present any symptomatic cluster (n = 29). The most prevalent combination was the one with the 5 factors (n = 54).

Regression analyses

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to partial out the specific contribution of the five symptomatic clusters to the functional impairment of adults with ADHD. The five obtained factors were simultaneously entered as predictors in the model. Results are presented in Table 3. Regarding the 7 domains of life impairment of the WFIRS, predictors accounted for 8.9% to 37.2% of the variance. Regarding the WFIRS-Family subscale, the “emotional instability”, “impulsivity” and the “sleep problems” factors were the main predictor of scores (β = 0.37, β = 0.24 and β = 0.09; p < 0.05 respectively). These factors were also the main predictors for the WFIRS-Social functioning subscale (β = 0.34, β = 0.14 and β = 0.17; p < 0.05 respectively). The “impulsivity”, the “inattention/disorganization” and the “sleep problems” factors were the main predictors of the WFIRS-Work and WFIRS-Daily skills subscales (β = 0.28, β = 0.40, β = 0.13, and β = 0.34, β = 0.35, β = 0.18 respectively). Regarding the WFIRS-Self-concept subscale, the main predictors consisted in “emotional instability”, “overactivation” and the “inattention/disorganization” factors (β = 0.58, β = -0.11, and β = 0.19). For the WFIRS-Risky behaviors subscale the factors “emotional instability”, “inattention/disorganization” and “overactivation” were the main predictors (β = 0.09, β = 0.47, and β = 0.14).

To partial out the specific contribution of childhood maltreatment to the obtained factors (i.e. emotional lability, impulsivity, overactivation, inattention/disorganization and sleep problems) a simple regression was conducted using the CTQ-SF as a predictor variable. Results are presented in Table 4. Regarding the “emotional instability”, the ‘impulsivity” and the “sleep problems” factors, the CTQ-SF accounted respectively for 10.6%, 4.5% and 2.4% of the variance (F = 47.08; p < 0.001; F = 19.46, p < 0.001; F = 10.41, p = 0.001).

Discussion

This study aimed at identifying the clinical patterns of ED in adults with ADHD, through the use of self-reported questionnaires assessing several psychological dimensions potentially related to ED. Overall, our results suggest that the clinical presentation of adults with ADHD is broader than the classic symptomatic triad comprising inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity [4]. Indeed, using factor analysis, the sets of symptoms found here are highly similar to the clinical picture of adult ADHD described by Asherson [12], and include ED, overactivity, and sleep problems. Indeed, the factor analysis revealed five symptomatic dimensions which seem to account for the clinical presentation of most adult ADHD cases. Emotional difficulties were part of three out of five clusters, suggesting that this symptom is central in the clinical picture of adult ADHD [14, 31, 34, 42, 63, 90]. The first cluster, i.e., “emotional instability”, refers to emotional fluctuations and the vulnerability to negative emotions. The second cluster, i.e., “impulsivity”, refers to the excessive emotional reactions in response to both positive and negative emotional situations and is in line with the concept of emotional impulsivity described by Barkley and Fischer [40] and Barkley [91]. The third cluster, labelled “overactivation”, encompasses several strengths of functioning of adults with ADHD, including hyperthymic temperament traits, racing thoughts and creativity. This factor is akin to the positive emotionality factor recently highlighted in the literature [92]. The other two factors were independent of emotional difficulties. The fourth and the fifth clusters, respectively labelled “inattention/disorganization” and “sleep problems”, refer to attention and cognitive problems and sleep difficulties.

Our results are in line with those of prior studies using factor analysis which suggest that inattention, associated with executive dysfunction, is a robust feature of ADHD [26, 35, 67, 75, 92, 93]. Indeed the factor “inattention/disorganization” concerns 61.38% of our sample of adults with ADHD. This number is similar to that referring to the “emotional instability” and/or “impulsivity” factors, as 67.52% of our sample presented with at least one of these symptoms. Interestingly, some authors suggest that considering two ADHD phenotypes (i.e. an inattention presentation and a combined inattention and dysregulated emotions presentation) may be more accurate than the classic three phenotypes (inattention, hyperactive-impulsive and combined presentations) [35, 75]. Regarding studies supporting the centrality of ED in adult ADHD [14, 26, 31, 34, 35, 42, 63, 90, 94], our results add to those and are the first using several measures of ED. Moreover, consistent with a number of recent studies on ED in ADHD, our results indicate that a large majority of individuals identified as presenting the two ED factors had the combined presentation (82.03%) compared to the inattentive presentation (14.84%; 24,35,67).

Regarding the patterns of ED found in adult ADHD, consistent with the study led by Weibel et al. [26], we found that ED can be conceptualized along two dimensions: the emotional instability dimension, associated with vulnerability to sadness, sensitivity to environmental stressors, and their behavioral implications, and the emotional impulsivity dimension. However, those two dimensions rarely occur alone. Indeed, only 17.14% and 11,76% of the participants were concerned with the “emotional instability” or the “impulsivity” factor alone. This can be explained by the temporal model of emotions symptoms in ADHD [63]. In this model, excessive experience or high sensitivity to emotional stimulations and further regulation strategies are distinguished. Faraone et al. [63] posit that emotional instability and emotional impulsivity are inherently associated, resulting from a hypersensitive emotional generation, whereas deficient late emotion regulation strategies are rather involved in the slower return to an emotional neutral state. Of note, emotional impulsivity and emotional lability are thought to be the main features of the ED experience in the ADHD combined presentation [63]. In contrast, deficient emotional self-regulation without emotional impulsivity is hypothesized to be more specifically associated with the ADHD inattentive presentation [63]. In line with Faraone et al.’s assumptions [63], we found that the combined ADHD presentation was the most prevalent among patients presenting with both “emotional instability” and “impulsivity” factors (82.17%), while the inattentive ADHD presentation concerned only 14.73% of those patients. This suggests that different mechanisms may underpin the experience of ED in the combined and the inattentive presentation of ADHD. Furthermore, consistent with a number of studies, the ED factors contributed to most functional difficulties of adults with ADHD, i.e. behavioral, academic and social impairment [39, 40, 92, 95, 96]. For instance, in a recent factor analysis study, Pallucchini et al., [92] also identify an ED factor, and patients with ED presented with the most severe impairments. In addition to the contribution of ED to the functional impairment associated with adult ADHD, our results suggest a weak, albeit significant contribution of childhood maltreatment to ED and sleep problems. This is consistent with a number of studies suggesting that environmental factors and especially childhood maltreatment are involved in the development and the severity of ED in ADHD [54], similar to other disorders, such as BPD and BD [54, 97, 98].

In contrast to ED, the factor “overactivation” was positively associated with increased self-esteem and did not contribute to any functional difficulties. Importantly, there is a growing number of studies focusing on the strengths of the ADHD functioning, shifting therefore from the deficit-focus view of ADHD [99,100,101]. Creativity, racing thoughts, motor hyperactivity and hyperthymic temperament are the dimensions composing the “overactivation” factor. Interestingly, in a qualitative study on the ADHD strengths, Sedgwick et al. [101] found that racing thoughts and creativity belonged to a global theme, labelled cognitive dynamism. Cognitive dynamism included ceaseless mental activity akin to racing thoughts found in BD [36, 101, 102]. Furthermore, Segdwick et al. [101] also found that motor hyperactivity may be beneficial. Indeed, increased physical energy leads patients to engage in physical activities, which may, in turn, contribute to their well-being. In line with the positive emotionality factor identified by Pallucchini et al. [92], consisting of few emotional control difficulties, the hyperthymic temperament was part of our “overactivation” factor. Individuals presenting with hyperthymic temperament display exuberance, tirelessness, sensation seeking and a high level of energy [80]. Although the hyperthymic temperament is not among the most prevalent affective temperament in adults with ADHD [70, 72], it could characterize a subgroup of high-functioning people with ADHD whom present with limited functional impairments [99]. Indeed, in the general population, the hyperthymic temperament has been found to have a protective effect against the development of mental health issues [103], such as addiction [104, 105]. Moreover, in adults with bipolar disorder, hyperthymic temperament traits are a protective factor against relapse, severity of anxiety and suicidality [106]. Overall, individuals presenting with the “overactivation” factor, reported more positive aspects of ADHD and fewer emotional difficulties, which are involved in the functional impairment associated with ADHD.

We acknowledge some limitations to this study. First, given the naturalistic approach used, the adults with ADHD recruited presented with different comorbidities, which may have influenced the factor analysis. Secondly, since our sample of adults with ADHD was recruited in a clinical setting, it included people who sought care and were likely to present with significant functional impairment,. Hence, participants probably experienced more severe ADHD and ED symptoms than the general adult ADHD population, limiting the generalization of our results to the general ADHD. For instance, the overactivation features might be more prominent in the general ADHD community, including adults who have a satisfactory quality of life. A replication of this study in the general population is warranted to capture a broader spectrum of ADHD and ED symptoms severity and to confirm the distribution of symptomatic factors more generally. Third, given the sample size, we were unable to perform a factor analysis on the items of each questionnaire and used the global scale or subscales scores. An item-based analysis could yield a more accurate description of ADHD. Nevertheless, this study counted a total of 20 measures allowing a large scanning of the ADHD functioning. Future studies should investigate the relative importance of each symptom using a network analysis approach. As an example Silk et al. [107] used this statistical method on the 18 ADHD diagnostic criteria described in the DSM-5 and found that motor hyperactivity is as central as the tendency of losing objects in ADHD.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified five symptomatic clusters that characterized adults with ADHD. Among them, ED appears as a central bi-factorial symptom, encompassing emotional lability and emotional impulsivity, contributing to greater functional impairment and partially explained by childhood maltreatment. However, adult ADHD cannot be reduced to a collection of clinical impairing symptoms, given that several features can be characteristic of high functioning ADHD and be involved in compensatory strategies used to overcome difficulties. In sum, there are relevant features beyond the classical symptomatic triad that may have significant implications for ADHD identification in adults. However, beyond functional impairment, ADHD may also be characterized by functional strengths.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- BSL-23:

-

Borderline Symptom List-23

- CPAC:

-

Cognitive Processes Associated with Creativity

- CTQ-SF:

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short-Form

- ED:

-

Emotion Dysregulation

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- ISI:

-

Insomnia Severity Scale

- RCTQ-13:

-

Racing and Crowded Thoughts Questionnaire-13 item

- SR-WRAADDS:

-

Self-Reported Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale

- TEMPS-A:

-

Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego Autoquestionnaire

- UPPS-P:

-

Urgency Premeditation Perseverance Sensation seeking Positive urgency

- WFIRS:

-

Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale

References

Fayyad J, Graaf RD, Kessler R, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Demyttenaere K, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(5):402–9.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23.

Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11(11):04009.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. 1520.

Brod M, Pohlman B, Lasser R, Hodgkins P. Comparison of the burden of illness for adults with ADHD across seven countries: a qualitative study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;14(10):47.

Kooij, Bijlenga D, Salerno L, Jaeschke R, Bitter I, Balázs J, et al. Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;56(1):14–34.

Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV. Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):816–8.

Adler. Clinical presentations of adult patients with ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 3):8–11.

Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Asherson PJ, Larsson H. Developmental twin study of attention problems: high heritabilities throughout development. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70(3):311–8.

Larsson H, Dilshad R, Lichtenstein P, Barker ED. Developmental trajectories of DSM-IV symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: genetic effects, family risk and associated psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(9):954–63.

Weyandt LL, Iwaszuk W, Fulton K, Ollerton M, Beatty N, Fouts H, et al. The Internal Restlessness Scale: Performance of College Students With and Without ADHD. J Learn Disabil. 2016. Cited 2020 Apr 30; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00222194030360040801.

Asherson P. Clinical assessment and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Expert Rev Neurother. 2005;5(4):525–39.

Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Faraone SV, Rohde LA. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: key conceptual issues. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(6):568–78.

Shaw, Stringaris A, Nigg J, Leibenluft E. Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(3):276–93.

Aldao A, Gee DG, De Los Reyes A, Seager I. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in the development of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: Current and future directions. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(4pt1):927–46.

Kring AM, Sloan DM. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: A Transdiagnostic Approach to Etiology and Treatment. Guilford Press. Cited 2022 Jul 12. Available from: https://www.guilford.com/books/Emotion-Regulation-and-Psychopathology/Kring-Sloan/9781606234501/contents.

Sloan E, Hall K, Moulding R, Bryce S, Mildred H, Staiger PK. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;57:141–63.

Bradley B, DeFife JA, Guarnaccia C, Phifer J, Fani N, Ressler KJ, et al. Emotion dysregulation and negative affect: association with psychiatric symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):685–91.

Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Fang A, Asnaani A. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(5):409–16.

Klassen LJ, Katzman MA, Chokka P. Adult ADHD and its comorbidities, with a focus on bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1):1–8.

Philipsen A. Differential diagnosis and comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) in adults. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(1):i42–6.

Wender. ATTENTION-DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER IN ADULTS. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(4):761–74.

Beheshti A, Chavanon ML, Christiansen H. Emotion dysregulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):120.

Gisbert L, Richarte V, Corrales M, Ibáñez P, Bosch R, Bellina M, et al. The Relationship Between Neuropsychological Deficits and Emotional Lability in Adults With ADHD: J Atten Disord. 2018 Cited 2020 Apr 30; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1087054718780323.

Hirsch O, Chavanon ML, Christiansen H. Emotional dysregulation subgroups in patients with adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): a cluster analytic approach. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11.

Weibel S, Bicego F, Muller S, Martz E, Costache ME, Kraemer C, et al. Two facets of emotion dysregulation are core symptomatic domains in adult ADHD: results from the SR-WRAADDS, a broad symptom self-report questionnaire. J Atten Disord. 2022;26(5):767–78.

Able SL, Johnston JA, Adler LA, Swindle RW. Functional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHD. Psychol Med. 2007;37(1):97–107.

Corbisiero S, Stieglitz RD, Retz W, Rösler M. Is emotional dysregulation part of the psychopathology of ADHD in adults? Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2013;5(2):83–92.

Rüfenacht E, Euler S, Prada P, Nicastro R, Dieben K, Hasler R, et al. Emotion dysregulation in adults suffering from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a comparison with borderline personality disorder (BPD). Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregulation. 2019;6(1):11.

Barkley RA. Differential diagnosis of adults with ADHD: the role of executive function and self-regulation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):e17.

Corbisiero S, Mörstedt B, Bitto H, Stieglitz RD. Emotional dysregulation in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-validity, predictability, severity, and comorbidity. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(1):99–112.

Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, Robison D, Robison RJ, Wender PH. Psychometric properties of the Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale. Psychol Assess. 2013;25(3):942–50.

Richard-Lepouriel H, Etain B, Hasler R, Bellivier F, Gard S, Kahn JP, et al. Similarities between emotional dysregulation in adults suffering from ADHD and bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2016;1(198):230–6.

Skirrow C, Asherson P. Emotional lability, comorbidity and impairment in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1):80–6.

Reimherr FW, Roesler M, Marchant BK, Gift TE, Retz W, Philipp-Wiegmann F, et al. Types of Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Replication Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):0–0.

Martz E, Bertschy G, Kraemer C, Weibel S, Weiner L. Beyond motor hyperactivity: Racing thoughts are an integral symptom of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113988.

Rösler M, Retz W, Fischer R, Ose C, Alm B, Deckert J, et al. Twenty-four-week treatment with extended release methylphenidate improves emotional symptoms in adult ADHD. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(5):709–18.

Surman CBH, Biederman J, Spencer T, Miller CA, Petty CR, Faraone SV. Neuropsychological Deficits Are Not Predictive of Deficient Emotional Self-Regulation in Adults With ADHD: J Atten Disord. 2013. Cited 2020 Apr 30; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1087054713476548.

Ben-Dor Cohen M, Eldar E, Maeir A, Nahum M. Emotional dysregulation and health related quality of life in young adults with ADHD: a cross sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):270.

Barkley RA, Fischer M. The unique contribution of emotional impulsiveness to impairment in major life activities in hyperactive children as adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):503–13.

Skirrow C, Ebner-Priemer U, Reinhard I, Malliaris Y, Kuntsi J, Asherson P. Everyday emotional experience of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence for reactive and endogenous emotional lability. Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3571–83.

Surman CBH, Biederman J, Spencer T, Miller CA, McDermott KM, Faraone SV. Understanding deficient emotional self-regulation in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a controlled study. ADHD Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2013;5(3):273–81.

Vidal R, Valero S, Nogueira M, Palomar G, Corrales M, Richarte V, et al. Emotional lability: the discriminative value in the diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1712–9.

Brikell I, Kuja-Halkola R, Larsson H. Heritability of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet Off Publ Int Soc Psychiatr Genet. 2015;168(6):406–13.

Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: a meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):608–37.

Hudziak JJ, Derks EM, Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Boomsma DI. The genetic and environmental contributions to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as measured by the Conners’ Rating Scales-Revised. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1614–20.

Larsson H, Chang Z, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P. The heritability of clinically diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Psychol Med. 2014;44(10):2223–9.

Biederman J, Spencer T, Lomedico A, Day H, Petty CR, Faraone SV. Deficient emotional self-regulation and pediatric attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a family risk analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(3):639–46.

Sobanski E, Banaschewski T, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Chen W, Franke B, et al. Emotional lability in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): clinical correlates and familial prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(8):915–23.

Surman CBH, Biederman J, Spencer T, Yorks D, Miller CA, Petty CR, et al. Deficient emotional self-regulation and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a family risk analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):617–23.

Rucklidge JJ, Brown DL, Crawford S, Kaplan BJ. Retrospective reports of childhood trauma in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2006;9(4):631–41.

Becker-Blease KA, Freyd JJ. A preliminary study of ADHD symptoms and correlates: do abused children differ from nonabused children? J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2008;17(1):133–40.

Sanderud K, Murphy S, Elklit A. Child maltreatment and ADHD symptoms in a sample of young adults. Eur J Psychotraumatology. 2016;7(1):32061.

Rüfenacht E, Pham E, Nicastro R, Dieben K, Hasler R, Weibel S, et al. Link between History of Childhood Maltreatment and Emotion Dysregulation in Adults Suffering from Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder or Borderline Personality Disorder. Biomedicines. 2021;9(10):1469.

Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004;364(9432):453–61.

Moukhtarian TR, Mintah RS, Moran P, Asherson P. Emotion dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregulation. 2018;5(1):9.

Moukhtarian TR, Reinhard I, Moran P, Ryckaert C, Skirrow C, Ebner-Priemer U, et al. Comparable emotional dynamics in women with ADHD and borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregulation. 2021;8(1):6.

Weiner L, Perroud N, Weibel S. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder And Borderline Personality Disorder In Adults: A Review Of Their Links And Risks</p>. Vol. 15, Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. Dove Press; 2019. Cited 2020 Apr 30. 3115–29. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-and-borderline-personality-di-peer-reviewed-article-NDT.

Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Kleindienst N, Welch SS, Reisch T, Reinhard I, et al. State affective instability in borderline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory monitoring. Psychol Med. 2007;37(7):961–70.

Ebner-Priemer UW, Welch SS, Grossman P, Reisch T, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Psychophysiological ambulatory assessment of affective dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150(3):265–75.

Ebner-Priemer UW, Trull TJ. Ecological momentary assessment of mood disorders and mood dysregulation. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(4):463–75.

Santangelo P, Bohus M, Ebner-Priemer UW. Ecological momentary assessment in borderline personality disorder: a review of recent findings and methodological challenges. J Personal Disord. 2014;28(4):555–76.

Faraone SV, Rostain AL, Blader J, Busch B, Childress AC, Connor DF, et al. Practitioner review: emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - implications for clinical recognition and intervention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(2):133–50.

Philipsen A, Limberger MF, Lieb K, Feige B, Kleindienst N, Ebner-Priemer U, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as a potentially aggravating factor in borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):118–23.

Posner, Kass E, Hulvershorn L. Using stimulants to treat ADHD-related emotional lability. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):478.

van Dijk FE, Lappenschaar M, Kan CC, Verkes RJ, Buitelaar JK. Symptomatic overlap between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder in women: the role of temperament and character traits. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):39–47.

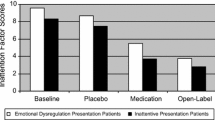

Reimherr FW, Marchant BK, Gift TE, Steans TA, Wender PH. Types of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): baseline characteristics, initial response, and long-term response to treatment with methylphenidate. ADHD Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2015;7(2):115–28.

Wender, Wolf LE, Wasserstein J. Adults with ADHD. An overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;931:1–16.

Landaas ET, Halmøy A, Oedegaard KJ, Fasmer OB, Haavik J. The impact of cyclothymic temperament in adult ADHD. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1):241–7.

Pinzone V, De Rossi P, Trabucchi G, Lester D, Girardi P, Pompili M. Temperament correlates in adult ADHD: A systematic review★★. J Affect Disord. 2019;1(252):394–403.

Philipsen A, Feige B, Hesslinger B, Scheel C, Ebert D, Matthies S, et al. Borderline typical symptoms in adult patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2009;1(1):11–8.

Ekinci S, Özdel K, Öncü B, Çolak B, Kandemir H, Canat S. Temperamental characteristics in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a comparison with bipolar disorder and healthy control groups. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(2):137–42.

Torrente F, López P, Lischinsky A, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Manes F. Depressive symptoms and the role of affective temperament in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a comparison with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2017;15(221):304–11.

Storebø OJ, Simonsen E. Is ADHD an early stage in the development of borderline personality disorder? Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68(5):289–95.

Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, Wender PH, Gift TE. Psychometric properties of the Self-Report Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale. Ann Clin Psychiatry Off J Am Acad Clin Psychiatr. 2015;27(4):267–77 (quiz 278–82).

Billieux J, Rochat L, Ceschi G, Carré A, Offerlin-Meyer I, Defeldre AC, et al. Validation of a short French version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(5):609–15.

Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, Stieglitz RD, Domsalla M, Chapman AL, et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32–9.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Akiskal HS, Mendlowicz MV, Jean-Louis G, Rapaport MH, Kelsoe JR, Gillin JC, et al. TEMPS-A: validation of a short version of a self-rated instrument designed to measure variations in temperament. J Affect Disord. 2005;85(1):45–52.

Weiner L, Ossola P, Causin JB, Desseilles M, Keizer I, Metzger JY, et al. Racing thoughts revisited: a key dimension of activation in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;1(255):69–76.

Miller A. Cognitive processes associated with creativity : scale development and validation. undefined. 2009 Cited 2022 May 25; Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Cognitive-processes-associated-with-creativity-%3A-Miller/8cd852a59a4da907c1dc18f0d1b63e1909893284.

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307.

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–5.

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–6.

Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Weibel S, Weiss M, Gachet M, Guichard K, Bioulac S, et al. Validation of the French Version of the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale-Self-Report in a Large Cohort of Adult Patients With ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(10):1148–59.

Weiss MD, McBride NM, Craig S, Jensen P. Conceptual review of measuring functional impairment: findings from the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(4):155–64.

Schreiber JB. Issues and recommendations for exploratory factor analysis and principal component analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(5):1004–11.

Hartigan JA, Wong MA. Algorithm AS 136: A K-Means Clustering Algorithm. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1979;28(1):100–8.

Hirsch O, Chavanon M, Riechmann E, Christiansen H. Emotional dysregulation is a primary symptom in adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J Affect Disord. 2018;1(232):41–7.

Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment, 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. xiii, p. 898. (Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment, 4th ed).

Pallucchini A, Carli M, Scarselli M, Maremmani I, Perugi G. Symptomatological variants and related clinical features in adult attention deficit hyperactive disorder. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):922.

Adler LA, Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Berglund P, Alperin S, Kessler RC. The structure of adult ADHD. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26(1): e1555.

Biederman J, DiSalvo M, Woodworth KY, Fried R, Uchida M, Biederman I, et al. Toward operationalizing deficient emotional self-regulation in newly referred adults with ADHD: A Receiver operator characteristic curve analysis. Eur Psychiatry J Assoc Eur Psychiatr. 2020;63(1): e21.

Bunford N, Evans SW, Langberg JM. Emotion Dysregulation Is Associated With Social Impairment Among Young Adolescents With ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(1):66–82.

Knouse LE, Traeger L, O’Cleirigh C, Safren SA. Adult ADHD Symptoms and Five Factor Model Traits in a Clinical Sample: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(10): https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a5bf33.

Krause-Utz A, Erol E, Brousianou AV, Cackowski S, Paret C, Ende G, et al. Self-reported impulsivity in women with borderline personality disorder: the role of childhood maltreatment severity and emotion regulation difficulties. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregulation. 2019;6:6.

Khosravani V, Berk M, Sharifi Bastan F, Samimi Ardestani SM, Wrobel A. The effects of childhood emotional maltreatment and alexithymia on depressive and manic symptoms and suicidal ideation in females with bipolar disorder: emotion dysregulation as a mediator. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25(1):90–102.

Lesch KP. ‘Shine bright like a diamond!’: is research on high-functioning ADHD at last entering the mainstream? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(3):191–2.

Mahdi S, Viljoen M, Massuti R, Selb M, Almodayfer O, Karande S, et al. An international qualitative study of ability and disability in ADHD using the WHO-ICF framework. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(10):1219–31.

Sedgwick JA, Merwood A, Asherson P. The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. ADHD Atten Deficit Hyperact Disord. 2019;11(3):241–53.

Martz E, Weibel S, Weiner L. An overactive mind: Investigating racing thoughts in ADHD, hypomania and comorbid ADHD and bipolar disorder via verbal fluency tasks. J Affect Disord. 2022;1(300):226–34.

Karam EG, Salamoun MM, Yeretzian JS, Mneimneh ZN, Karam AN, Fayyad J, et al. The role of anxious and hyperthymic temperaments in mental disorders: a national epidemiologic study. World Psychiatry Off J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2010;9(2):103–10.

Khazaal Y, Gex-Fabry M, Nallet A, Weber B, Favre S, Voide R, et al. Affective temperaments in alcohol and opiate addictions. Psychiatr Q. 2013;84(4):429–38.

Rovai L, Maremmani AGI, Bacciardi S, Gazzarrini D, Pallucchini A, Spera V, et al. Opposed effects of hyperthymic and cyclothymic temperament in substance use disorder (heroin- or alcohol-dependent patients). J Affect Disord. 2017;15(218):339–45.

Luciano M, Steardo L, Sampogna G, Caivano V, Ciampi C, Del Vecchio V, et al. Affective Temperaments and Illness Severity in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Med Kaunas Lith. 2021;57(1):54.

Silk TJ, Malpas CB, Beare R, Efron D, Anderson V, Hazell P, et al. A network analysis approach to ADHD symptoms: More than the sum of its parts. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0211053.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Federica Gioia, from Department of Information Engineering & Bioengineering and Robotics Research Centre E. Piaggio, University of Pisa, for her help with the statistical analyses.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EM contributed to the study conception, performed the data acquisition and the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LW contributed to the study conception, the data acquisition and the manuscript revision. SW contributed to the study conception, the data acquisition and the manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Subjects provided a written consent prior to inclusion in the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculties of Medicine, Odontology, Pharmacy, Schools of Nursing, Physiotherapy, Maieutics and the University Hospitals of Strasbourg (N° 2018–27 of March 14, 2018).

Consent for publication

‘Not applicable’.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Martz, E., Weiner, L. & Weibel, S. Identifying different patterns of emotion dysregulation in adult ADHD. bord personal disord emot dysregul 10, 28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-023-00235-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-023-00235-y