Abstract

This study aims to elucidate the clinical and molecular characteristics, treatment outcomes and prognostic factors of patients with histone H3 K27-mutant diffuse midline glioma. We retrospectively analyzed 93 patients with diffuse midline glioma (47 thalamus, 24 brainstem, 12 spinal cord and 10 other midline locations) treated at 24 affiliated hospitals in the Kansai Molecular Diagnosis Network for CNS Tumors. Considering the term “midline” areas, which had been confused in previous reports, we classified four midline locations based on previous reports and anatomical findings. Clinical and molecular characteristics of the study cohort included: age 4–78 years, female sex (41%), lower-grade histology (56%), preoperative Karnofsky performance status (KPS) scores ≥ 80 (49%), resection (36%), adjuvant radiation plus chemotherapy (83%), temozolomide therapy (76%), bevacizumab therapy (42%), HIST1H3B p.K27M mutation (2%), TERT promoter mutation (3%), MGMT promoter methylation (9%), BRAF p.V600E mutation (1%), FGFR1 mutation (14%) and EGFR mutation (3%). Median progression-free and overall survival time was 9.9 ± 1.0 (7.9–11.9, 95% CI) and 16.6 ± 1.4 (13.9–19.3, 95% CI) months, respectively. Female sex, preoperative KPS score ≥ 80, adjuvant radiation + temozolomide and radiation ≥ 50 Gy were associated with favorable prognosis. Female sex and preoperative KPS score ≥ 80 were identified as independent good prognostic factors. This study demonstrated the current state of clinical practice for patients with diffuse midline glioma and molecular analyses of diffuse midline glioma in real-world settings. Further investigation in a larger population would contribute to better understanding of the pathology of diffuse midline glioma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diffuse midline glioma (DMG) harboring histone H3 K27 mutation is diagnosed as DMG, H3 K27-altered in World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System 2021 (CNS WHO 2021). It is characterized by the loss of histone H3 p.K28me3 (K27me3), which contains the H3 c.83A > T p.K28M(K27M) substitution in H3.3 (H3F3A) or H3.1 (HIST1H3B/C) [57]. DMG is categorized as a pediatric-type diffuse high-grade glioma in CNS WHO 2021 [57]. However, DMG may occur in adults as well as in children and adolescents, and this has created confusion over the diagnosis and treatment of adult diffuse gliomas, with differing definitions being used [14, 24, 26, 27, 33, 35, 42,43,44, 51, 55, 56, 60,61,62].

Essential information about DMG has been summarized in the WHO Blue Book [57]. Even after CNS WHO 2021, however, several researchers have reported additional findings [5, 6, 23, 27, 30, 32, 36, 53, 54, 58, 62]. Owing to its rarity, however, there are few comprehensive reports and there are remaining inconsistencies about DMG. There are major concerns regarding prediction of clinical behavior and outcomes in daily practice; there is a lack of real-world data on clinical and molecular characteristics and treatment outcomes. The current study investigates the prevalence and impact of previously-reported biomarkers.

DMG is defined as tumors located in areas such as the thalamus, the brainstem and the spinal cord, and occasionally in the pineal gland, the hypothalamus, and the cerebellum [57]. On the other hand, H3 K27M mutation has reportedly been detected in not only in tumors of these areas, but also in those of other locations, such as in the cerebral hemisphere, the corpus callosum, the ventricles, the basal ganglia, and the suprasellar region [1, 2, 7, 11, 14, 17, 19, 20, 23, 25, 31, 33, 39, 42, 47, 51, 55, 62] (Additional file 1: Table S1). As for the basal ganglia and corpus callosum, some researchers have regarded them as “midline” structures [1, 2, 7, 23, 25, 31, 39, 42, 51, 55, 62], while others have regarded them as “non-midline” structures and these tumors have thus been excluded from DMG [11, 19, 40, 60] (Additional file 1: Table S1). Discrimination between the “midline” and “non-midline” structures for definition of DMG therefore lacks consensus.

For the present study, we reviewed the inclusion criteria of DMG used in previous reports that focused upon the midline structures. We collected histone H3 K27M-mutant diffuse gliomas at the midline location in the Kansai Molecular Diagnosis Network for CNS Tumors (Kansai Network) cohort. This is a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study of 93 cases of DMG treated at 24 hospitals in the Kansai Network. We aim to elucidate both clinical and pathological features of cases of DMG, as well as treatment outcomes and prognostic factors of patients with DMG in real-world settings.

Material and methods

Ethics

This study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Osaka National Hospital (No. 713), Wakayama Medical University (No. 98), Wakayama Rosai Hospital (No. 20 Res-17), and all collaborating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patient population and study design

This study included patients with histone H3-mutated gliomas who were treated at one of 27 institutions or hospitals participating in the Kansai Network [41]. Between May 2007 and July 2022, we collected a total of 4128 samples including all kinds of primary and recurrent gliomas from 72 institutions. From this databank, we focused on diffuse gliomas with histone H3 mutation and collected 118 cases (116 cases with H3F3A mutation and two cases with HIST1H3B mutation). Among the cases with H3F3A mutation, 107 cases had the K27M mutation, and nine cases had the G34R/V mutation. In this study, we examined 109 cases from 24 institutions, consisting of 107 cases with the K27M mutation and two cases with the HIST1H3B mutation. Patient selection is summarized in a flowchart in Fig. 1. Diagnosis of diffuse gliomas was initially confirmed by histopathological examination at each institution or hospital.

Tumor location (Kansai classification)

Preoperative images were available in 106 of the 109 cases (the anatomic tumor locations were identified by medical records in three cases). Neuroradiological assessments were performed by three experienced board-certified neurosurgeons (N.H., H.N., H.K.) and three additional senior board-certified neurosurgeons (J.F., K.M., Yo.Ka.) to reach a consensus. Tumor locations in this study were determined using the anatomical criteria as follows:

-

The main anatomical structure in which the tumor is solely located is defined as the tumor location, for example, the thalamus, the brainstem, the spinal cord, etc. (Additional file 4: Figure S1A).

-

If tumors were distributed across multiple anatomical regions in a contiguous manner, the presumed tumor origin site was determined based on the location of contrast-enhanced lesions and the progression pattern of FLAIR high-signal areas (Additional file 4: Figure S1B).

-

The cases in which non-contiguous multifocal tumors were detected and in which the main anatomical structure of the tumor could not be determined were defined as unclassified. For example, a case might equally harbor both the thalamus and the corpus callosum (Additional file 4: Figure S1C, D).

To discriminate between the “midline” and “non-midline” locations for this study, we applied the following criteria:

-

The thalamus, brainstem, spinal cord, pineal gland, hypothalamus, cerebellum, and ventricles were categorized as midline, and the basal ganglia and corpus callosum (as part of the cerebral hemisphere) were categorized as non-midline [45, 49, 50] (Table 1).

-

If a tumor was located at the basal ganglia or corpus callosum but mainly involved midline structures such as the thalamus or the brainstem, it was categorized as a midline tumor (Additional file 4: Figure S1C, E, Table 1).

-

If a tumor mainly involved the cerebral hemisphere, it was categorized as a non-midline tumor (Additional file 4: Figure S1F, Table 1).

Clinical information

Clinical information was collected from medical records including patient demographics, preoperative Karnofsky performance status (KPS) scores, the extent of surgical resection (EOR), adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy regimens, and survival time. EOR was classified according to the assessment by the surgeon as either gross total resection (GTR, 100% of the tumor was resected), subtotal resection (STR, 80–99%), partial resection (PR, < 80%), or biopsy. Patients either received no adjuvant treatment regimen, or those consisting of radiation (RT) plus chemotherapy, RT alone, or chemotherapy alone. Chemo-agents included temozolomide (TMZ), nimustine hydrochloride (ACNU), and bevacizumab (BEV). Adjuvant treatment regimens were determined by the attending physicians’ consideration of the patient’s condition.

Histopathological examination

All cases were subject to central pathology review by a senior board-certified neuropathologist (Yo.Ko). Histological diagnosis was made based on the CNS WHO 2021 classification [57].

Genetic analysis

Frozen or fresh tumor samples were obtained during surgery, and tumor genomic DNA was extracted from those tissues for genetic analysis [41]. Briefly, the methylation status of MGMT promoter (MGMTp) was analyzed by quantitative methylation-specific PCR after bisulfite modification of genomic DNA, and a threshold of ≥ 1% was used for MGMTp methylation. The presence of hotspot mutations in H3F3A, HIST1H3B, IDH1 (R132), IDH2 (R172), TERT promoter, BRAF (V600), FGFR1 (exon12 and exon14) and EGFR (exon 7 and exon20) genes, and all exons of TP53 were analyzed by Sanger sequencing [4, 52, 58].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS package and JMP Pro version 16 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and the SPSS Statistics version 29 (IBM, NY, USA, 2022). Categorized data were compared between subgroups using the Kruskal–Wallis test (age: continuous factor) and Pearson’s chi-square test (other items: nominal scale). Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) curves were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Preoperative imaging analysis resulted in 93 of 109 cases being categorized as having midline tumors (diffuse midline tumor, DMG) (85%) and they were enrolled in this study. The other sixteen cases (15%) were categorized as having non-midline tumors.

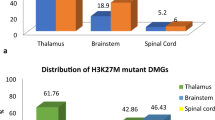

The clinical and molecular characteristics of the 93 patients analyzed in this study are shown in Table 2. Anatomical tumor locations were classified into four groups: the thalamus group (47 cases), the brainstem group (24 cases), the spinal cord group (12 cases) and other midline locations group (10 cases) (Fig. 2a, Table 2). Other midline locations included the ventricle (two cases), the basal ganglia (two cases), and the cerebellum (2 cases), and four cases were unclassified. Cases in the basal ganglia and unclassified cases mainly involved midline locations. Distribution of the patients’ age and sex are shown in Fig. 2b, and detailed information on each patient is shown as a tile panel in Fig. 3.

Clinical characteristics

There were 55 men (59%) and 38 women (41%) with a median age of 31 years (range 4–78 years). As shown in Figs. 2b and 3, only 26 patients were ≤ 18 years old (28%), and just seven patients were ≥ 70 years old (8%). According to the tumor locations, there seems to be significant difference in age distribution at other midline locations vs. the thalamus, the brainstem and the spinal cord locations (p = 0.041) (Table 2). As for sex, male predominance may exist in each location, but without significant difference (p = 0.809) (Table 2).

In MR images, gadolinium (Gd) enhancement of the tumor, as a high grade imaging feature, was observed in 68 tumors (73%) (Table 2 and Fig. 3). There was significant difference between groups (p = 0.016). Notably, Gd enhancement was not observed in 10 tumors (42%) in the brainstem group, a higher proportion than in the other groups. Hemorrhage was observed to have occurred in only one case in the thalamus [32].

Based on histopathological findings including morphology, cellularity, mitotic figures, and features of glioblastoma (GBM) (microvascular proliferation or necrosis) according to CNS WHO 2021 classification [57], 40 patients (43%) had GBM features and were diagnosed as having GBM. Thirty-six patients (39%) had diffusely infiltrative gliomas with histological features of anaplasia and displayed significant mitotic activity but without microvascular proliferation or necrosis, and they were diagnosed as having high-grade glioma (HGG) without GBM features. Sixteen patients (17%) had diffusely infiltrative glioma without histological features of anaplasia and displayed no/low mitotic activity without microvascular proliferation or necrosis, and they were diagnosed as having low-grade glioma (LGG). Approximately half of the cases with GBM features were in the thalamus and spinal cord groups (55% and 50%, respectively). Meanwhile, 79% of cases with LGG or HGG without features of GBM were in the brainstem group (Table 2).

Preoperative KPS scores ranged between 20 and 100 (median 70), and 46 patients had a score of ≥ 80 (49%). It may be notable that the preoperative KPS score was ≤ 70 in 67% cases in the spinal cord group. However, distribution of preoperative KPS score was not significantly different between tumor locations (p = 0.568).

Regarding EOR, 5 (5%), 11 (12%), 18 (19%), and 59 (63%) patients underwent GTR, STR, PR, and biopsy, respectively. Regardless of tumor locations, biopsy tended to be performed: it was performed in the thalamus, the brainstem, the spinal cord, and in other locations in 53%, 79%, 67% and 70% of cases, respectively (Table 1). EOR was not significantly different between tumor locations (p = 0.05). Surgical resection (46%) was more common in the thalamus group (46%) than in the other groups.

After surgery, 86 patients received adjuvant treatments of radiation (RT) and/or chemotherapy (93%). Although 82 patients underwent adjuvant RT, radiation was finally delivered for 86 patients (93% of the cohort), in which 82 patients (95%) and 74 patients (80%) received ≥ 40 Gy and ≥ 50 Gy, respectively (Table 2). The spinal cord group was significantly more likely to receive a lower radiation dose than other groups (p < 0.001). Chemotherapy was administered in 81 cases (87%), in which 76 patients received TMZ and only one patient in the thalamus group received ACNU with RT (Table 2, Fig. 3). BEV was administered with RT in 39 cases (42%). As shown in Table 2, adjuvant treatment regimen included RT + TMZ + BEV (35 cases, 38%), RT + TMZ (37 cases, 40%), RT + ACNU (1 case, 1%), RT + BEV (4 cases, 4%), RT alone (5 cases, 5%) and TMZ alone (4 cases, 4%), and were not significantly associated with tumor locations (p = 0.588). Meanwhile, bis-chloroethyl-nitrosourea wafers were placed in one case of the other midline location group. Tumor-treating fields therapy was applied in three cases in the thalamus in adult patients.

The observation period ranged between 0.5 and 63.5 months (median 15.6 months). During the observation period, tumor progression was observed in 58 patients (58/77, 75%). Repeat surgical resection was performed in seven cases (7/58, 12%). According to tumor locations, 6 of the 30 patients with a tumor in the thalamus and 1 of the 15 patients with a tumor in the brainstem underwent repeat resection [22] (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Molecular characteristics

As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3, HIST1H3B p.K27M mutation was observed in only two cases in the thalamus (2%) and all other cases had H3F3A p.K27M mutation (98%). IDH1/2 was wild-type in all cases, regardless of the tumor location. TERT promoter mutations were observed in only three cases in the thalamus (3%). MGMT promoter methylation was found in nine cases (10%) across tumor locations: five cases in the thalamus (11%), one case in the brainstem (4%), one case in the spinal cord, and two cases in other locations (20%), but there was no statistical difference (p = 0.304). TP53 mutation was detected in approximately half of cases across tumor locations (57%); there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.207). BRAF p.V600E was observed in only one case in the thalamus (1%). This patient had co-occurrence of H3 p.K27M and BRAF p.V600E mutations. FGFR1 mutation was found in 13 cases across tumor locations (14%), but there was no significant difference in frequency between the four locations (p = 0.619). Moreover, there was no significant difference between brainstem location (n = 24) and non-brainstem locations (n = 69) (p = 0.215). Notably, FGFR1 mutations were observed in almost all adult cases with the exception of one pediatric case in the brainstem (Fig. 3). In the cases harboring FGFR1 mutation, TP53 mutation occurred in five cases (5/13, 38%). EGFR mutation was observed in three patients (3%) (one in the thalamus, two in the brainstem). These cases can be diagnosed as DMG, EGFR-mutant, one subtype in DMG, H3 K27-altered.

Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors

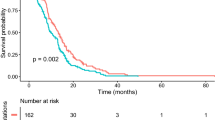

PFS was reported in 77 cases, and OS was reported in 87 cases. Tumor progression was observed in 58 patients (58/77, 75%). Sixty patients had died by the time of analysis (60/87, 69%). Median PFS was 9.9 months, and median OS (mOS) was 16.6 months (Fig. 4). This was similar to previous reports regarding the mOS (Additional file 2: Table S2). There was no significant difference in PFS or OS between the four tumor location groups (p = 0.676 and 0.132, respectively, Fig. 4). Patients (> 18 years) did not have significantly different OS (16.7 months) compared with 15.3 months in those ≤ 18 years old (p = 0.648) (Fig. 5a, Table 3). Women had significantly longer OS than men (27.6 vs. 14.4 months) (p = 0.015) (Fig. 5b, Table 3). In analysis based on specific locations, any differences were without significance: the thalamus (p = 0.116), the brainstem (p = 0.115), the spinal cord (p = 0.234), other locations (p = 0.274) (Additional files 6, 7, 8, 9: Figures S3b, S4b, S5b, S6b). As for histopathological findings, there was no significant difference in OS between the LGG group (27.6 months), the HGG without features of GBM group (12.4 months), and the HGG with features of GBM group (17.1 months) (p = 0.546). Moreover, the group with GBM features did not have significantly different OS (17.1 months) compared with the LGG and HGG without features of GBM groups (14.4 months) (p = 0.069) (Additional file 5: Figure S2a, b, Table 3). Patients with preoperative KPS score of < 80 survived for a shorter time than those with KPS 80–100 (12.0 vs. 18.4 months) (p = 0.025) (Fig. 5c, Table 3), while those with preoperative KPS score of < 70 survived without significant difference to those with KPS score 70–100 (12.8 vs. 17.3 months) (p = 0.086) (Additional file 5: Figure S2c). Patients in the group that underwent surgical resection (GTR + STR + PR) tended to survive longer than those who received biopsy (21.8 vs. 14.4 months), but this difference was not significant (p = 0.090) (Fig. 5d, Table 3). There was no significant survival difference between GTR + STR and PR + biopsy groups (p = 0.060), but patients in the GTR + STR group tended to survive longer than those in the PR + biopsy group (29.9 vs. 14.7 months) (Additional file 5: Figure S2d, Table 3). The repeat surgical resection group tended to have prolonged OS compared with those without surgical resection (31.5 vs. 16.7 months) (p = 0.104) (Additional file 5: Figure S2e). Patients who received adjuvant RT + TMZ ± BEV had significantly longer OS than those who received RT ± BEV or TMZ ± BEV (17.3 vs. 12.0 or 7.5 months) (p = 0.016) (Fig. 5e). RT + TMZ ± BEV group had significantly longer OS than others (p = 0.031) (Additional file 5: Figure S2f, Table 3). As for TMZ therapy, there was no significant survival difference between the TMZ (+) and (−) groups (17.3 vs. 11.1 months) (p = 0.08) (Additional file 5: Figure S2g, Table 3), and regarding BEV therapy, there was no significant difference in survival between the BEV (+) and (−) groups (16.6 vs. 16.0 months) (p = 0.933) (Additional file 5: Figure S2h). This was also similar to the trend in the adjuvant phase (p = 0.477) (Additional file 5: Figure S2i). There was no significant difference in survival between the RT(+) and RT(−) groups (16.8 vs. 7.5 months) (p = 0.063), but the RT(+) group tended to survive longer than the RT(−) group (Additional file 5: Figure S2j, Table 3).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to tumor locations. a Median progression-free survival of the cohort (n = 77) was 9.9 ± 1.0 (7.9–11.9, 95% CI) months. Thalamus (n = 43), 9.8 months; Brainstem (n = 18), 11.0 months; Spinal cord (n = 9), 9.1 months; Others (n = 7), 8.7 months. b Median overall survival (mOS) of the cohort (n = 87) was 16.6 ± 1.4 (13.9–19.3, 95% CI) months. Thalamus (n = 43), 19.2 months; Brainstem (n = 22), 12.4 months; Spinal cord (n = 12), 16.0 months; Others (n = 10), 12.0 months

Regarding the RT dose, there was significant difference in mOS between the groups (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5f). Median OS of RT ≥ 50 Gy group was the longest among the groups (17.3 months), and the difference with < 50 Gy groups (10.7 months) reached statistical significance (p = 0.008) (Additional file 5: Figure S2k, Table 3). Notably, there was also a statistical difference between ≥ 40 Gy and < 40 Gy groups (17.1 vs. 7.5 months) (p = 0.006) (Additional file 5: Figure S2l). With the exception of the spinal cord group, there was significant difference in mOS between the groups (p < 0.001) (Additional file 10: Figure S7a). Median OS of RT ≥ 50 Gy group was the longest between the groups (17.1 months), and the difference with < 50 Gy groups (7.5 months) reached statistical significance (p = 0.031) (Additional file 10: Figure S7b). However, there was no statistical difference between ≥ 40 Gy and < 40 Gy groups (16.8 vs. 7.5 months) (p = 0.144) (Additional file 10: Figure S7c).

Regarding molecular status, TERT promoter mutation status showed no significant difference in OS between wild-type (16.0 months) and mutated (31.7 months) groups (p = 0.533). However, the mutated group had too small a population (n = 3) to compare with the wild-type group (n = 84) (Fig. 6a, Table 3). Similarly, MGMT promoter methylated group (n = 8) did not have significant difference in OS compared with the unmethylated group (n = 79) (15.3 vs.16.7 months) (p = 0.967) (Fig. 6b, Table 3). As for TP53 status, no significant difference was found in OS between wild-type and mutated groups (17.3 vs. 14.7 months) (p = 0.754) (Fig. 6c, Table 3). The BRAF V600E group (n = 1) was too small for statistical analysis (Fig. 6d, Table 3). FGFR1 mutated group (n = 12) did not show longer OS than the wild-type group (n = 73) (11.6 vs.16.7 months) (p = 0.311) (Fig. 6e, Table 3). In the EGFR mutated group, a number of cases (n = 3), were shown to have shorter OS than the wild-type group (15.9 vs. 16.7 months) (p = 0.638) (Fig. 6f, Table 3).

We conducted a subgroup analysis of clinical and genetic prognostic factors for each location (Additional files 6, 7, 8, 9: Figures S3, S4, S5, S6). When stratifying by sex, no significant difference was observed in any of the locations (Additional files 6, 7, 8, 9: Figures S3b, S4b, S5b, S6b). In the thalamus, there was a significant difference in patients with KPS ≥ 80 and radiation dose (Additional file 6: Figure S3c, f). Similarly, in the brainstem, significant difference was observed in radiation dose (Additional file 7: Figure S4f). For the spinal cord and other midline locations, the sample size was small, potentially compromising the reliability of the observed significance (Additional files 8, 9: Figures S5, S6).

As the results of univariate analysis of the relationships between characteristics and estimated survival times for all cases of DMG, female sex, preoperative KPS score of ≥ 80, adjuvant RT + TMZ treatment and RT dose (≥ 50 Gy) were significantly associated with longer OS (Table 3).

The results of multivariate analysis of factors associated with OS are also shown in Table 3. Independent factors for good prognosis in the present cohort were identified as female sex and preoperative KPS score of ≥ 80.

Discussion

For the present study, we reviewed histone H3 K27M-mutant diffuse gliomas located at the midline structures in the Kansai Network dataset. We found 93 patients with midline DMG (47 in the thalamus, 24 in the brainstem, 12 in the spinal cord, and 10 in other midline locations). A separate article will report on non-midline tumors in more detail. The results of this study could be said to be representative of the current state of clinical practice for patients with DMG and molecular analyses of DMG in real-world settings.

Tumor location

Diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27-altered is defined as a tumor found in the thalamus, brainstem, spinal cord, and occasionally in the pineal gland, the hypothalamus or the cerebellum [57]. However, in clinical practice, H3 K27M-mutant diffuse gliomas could exist at the anatomically non-midline location. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S1, the definition of midline may have been confused in previous studies of DMG. For example, a tumor located at corpus callosum or basal ganglia was considered to be a midline tumor by some researchers, but as a non-midline tumor by others [1, 2, 7, 11, 19, 23, 25, 31, 39, 40, 42, 51, 55, 60, 62]. Diffuse glioma located at the thalamus along with the basal ganglia or both the thalamus and the corpus callosum was included in the studies of DMG [25, 28, 56]. The basal ganglia, embryologically associated with the cerebral cortex, is sometimes the location in which diffuse hemispheric glioma, H3 G34-mutant arise [19, 60]. From developmental and anatomical points of view, the cerebrum including the corpus callosum and the basal ganglia may be usually considered as non-midline structures [45, 49, 50]. However, a thalamic glioma involving the basal ganglia or corpus callosum would be categorized within the DMG [25, 28, 56]. On the other hand, there are some reports of the cerebral cortex being included in the location of the DMG [31, 38, 42, 51, 55, 60]. As for cerebellum, the vermis is apparently located at the midline, but diffuse glioma at the cerebellar hemisphere have sometimes been classified as non-midline tumors [21]. Meanwhile, a tumor in the ventricle was included in several DMG studies, although the ventricle was not described in CNS WHO 2021 [1, 2, 7, 14, 20, 31, 33, 47, 55, 57, 62]. Additionally, one study of DMG included diffuse glioma in the suprasellar region [51, 62]. For diffuse glioma extending from the spinal cord to the thalamus, one report introduced the concept of ‘diffuse growth along with brain axis’ [14]. Others have used the term ‘whole-brain type lesions’ for widespread lesions involving three or more contiguous lobes in the brain, and involvement of one or more traditional midline structures [39].

Based on these previous reports, we classified tumors in which the primary location was identified in the ventricles as ‘other midline locations’ (Table 1). Furthermore, among tumors which primarily involved the corpus callosum or basal ganglia, those which predominantly involved midline structures were classified as other midline locations, and tumors that primarily included the cerebral hemisphere were classified as non-midline, respectively (Table 1). In cases of non-contiguous, multifocal lesions where the primary location was indeterminate, we classified them as other midline locations if the main area involved midline structures, and as non-midline if it involved the cerebral hemispheres (Table 1). Using these criteria, we excluded 16 non-midline cases of 109 patients with H3 K27M-mutant diffuse glioma in Kansai Network cohort, as described in the Material and Methods section above. However, tumor locations of DMGs are sometimes heterogenous and complicated, so it may be difficult to identify the true tumor origin. We therefore suggest one standard definition for DMGs. However, this may still be incomplete, and future validation and reconsideration will be needed using a larger cohort, which we believe will improve the understanding of the features of DMGs.

Age

DMG is categorized in the pediatric-type diffuse high-grade gliomas of CNS WHO 2021; however, DMG may occur in adults, as well as in children and adolescents [14, 24, 26, 27, 33, 35, 42,43,44, 51, 55, 56, 60,61,62]. Previously, not-so-small percentages of adult cases were included in studies of DMG. For example, a recent study by Zheng et al. contained 57.3% patients aged ≥ 19 years, and other research by Williams et al. enrolled 48.6% patients aged ≥ 20 years [58, 62]. In our study cohort, the percentage of patients aged ≥ 19 years was 72.0%, so it may be higher than that of previous studies. There may be a higher occurrence in adults compared with in children [14, 56]. However, it should be taken into account that the limited number of pediatric cases may be due to the lower amount of surgical tissue sampling for brainstem tumors, which are more common in children than in adults [57]. DMG is generally thought to occur more commonly in children, but given the larger adult population, it is believed that the number of adult cases has become more prevalent as a result. DMG should nonetheless be considered as the differential diagnosis of adult diffuse gliomas.

Sex

Gliomas are known to have higher incidence and poorer prognosis in men [34, 48]. Numerous studies have indicated that women have a better prognosis than men, with factors such as hormones, metabolism, the immune system, genetic and molecular mechanisms, neurogenic niches and therapeutic responsiveness, among other factors, being suggested as reasons for this [8, 48]. None of the previous DMG reports found a significant difference in the prognosis by sex [23, 56, 62]. This study is thus the first report to list female sex a favorable prognostic factor in DMG.

Histopathological characteristics

In this study, histopathological features of DMGs were varied, and diagnosed as LGG (17%), HGG without features of GBM (39%) or HGG with features of GBM (43%). Zheng et al. reported common observations of microvascular proliferation (77/164, 47.0%), tumor cell necrosis (53/164, 32.3%), and multinucleated tumor cells (38/164, 23.2%) [62]. In this study, we observed similar microvascular proliferation (21/92, 23%), and tumor cell necrosis (28/92, 30%). These findings indicate that DMGs may show predominantly HGG or GBM histopathological features. On the other hand, some tumors showed LGG characteristics in morphology, despite their poor clinical prognosis. There might be a diagnostic limitation due to tiny biopsy specimens for DMG. Moreover, biopsies of low grade regions from tumors with high grade imaging features could be a potential confounder, especially in the biopsy cases; indeed, there were 24 cases (45%) in this study, comprising 11 cases in the thalamus group (50%), six cases in the brainstem group (31%), four cases in the spinal cord group (67%) and three cases in the others group (50%) (Additional file 3: Table S3). However, the present findings may indicate that H3 K27M-mutation does not always induce malignant histopathological phenotypes. Significance of histological malignant transformation occurring in DMGs therefore requires examination in future studies in combination with molecular analysis.

Molecular features

Regarding diagnostic molecular pathology, CNS WHO 2021 Blue Book stated that co-occurrence of histone H3 K27 mutation with IDH mutations is exceptional; correspondingly, all cases revealed IDH wildtype in our genetic analysis [57]. Similarly, TERT promoter mutations and MGMT promoter methylation represent rare events in DMGs. However, TERT mutated and MGMT methylated were detected in 3% and 9% of our cases, respectively, and these were mainly in the thalamus [57].

Only one patient in our cohort (a 4-year-old girl) had bilateral thalamic tumors harboring HIST1H3B p.K27M and EGFR mutations (Additional file 4: Figure S1B). As described in the WHO Blue Book, bi-thalamic tumors are more common in the EGFR-subtype of DMGs, most often occurring during childhood, with median age of 7–8 years [57].

Histone H3 K27M mutations are generally found to be associated with collaborating mutations of canonical cancer-associated pathways [57]. For example, TP53 mutations were found in 57% of our study cohort, being detected predominantly in H3.3 p.K28M (K27M)-mutant and EGFR-mutant cases according to a previous report [57]. BRAF p.V600E mutation co-occurred in just one case (1%) in this study with H3.3 p.K28M (K27M) mutation [57]. Gain-of-function mutation and genetic amplification of growth factor receptor involved in brain development are said to be common in H3 K27M-mutant DMGs, and FGFR1 mutation was found in 14% of patients in the present study [57]. A recent comprehensive genomic study of H3F3A-mutant high-grade gliomas revealed that FGFR1 hotspot point mutations (N546K and K656E) were exclusively identified in H3 K27M-mutant DMGs (64/304, 21%); these tend to occur in older patients (median age: 32.5 years) and mainly arise in the diencephalon [54, 58]. In this study, FGFR1 mutations were mainly observed outside of the brainstem, replicating the findings reported by Williams et al. [58]. The above findings were also similar to those observed in Japanese cases, and demonstrating a similar trend. Mutations were reportedly suggested to be associated with a favorable prognosis, and FGFR1 mutations are mutually exclusive with TP53 mutation [43]. TP53 mutations are associated with a poor prognosis [5, 43, 56]. However, these trends were not observed in our study cohort; these differences in prognostic factors and variations may be attributed to racial disparities. A future study will aim to validate these points within a larger sample size.

Relevance to treatments

Standard of care for DMG has never been determined, but several treatment options have been suggested, regardless of evidence. Surgical resection of DMG is often difficult, and in our cohort, biopsy tended to be undertaken (63%). However, aggressive resection may be attempted if feasible, and there were few cases in our cohort in which GTR was actually possible (5%) [23]. On the other hand, adjuvant RT + TMZ was conducted in the majority of our cohort (78%). Radiotherapy has been regarded as an important treatment option for brainstem gliomas, as is DMG [23]. TMZ concomitant with and adjuvant to RT is a widely used approach to GBM, but the role in cases of DMG has never been demonstrated [12, 46]. In our series, BEV was administered in 57% of cases, and there is a previous report of effectivity [59].

RT has been suggested in several studies to prolong the patients’ survival, although there is also a report to the contrary that radiotherapy does not influence prognosis [6, 23, 56]. Regarding the radiation dose, a standard protocol for DMG has never been established, but it often ranges from 36 to 65 Gy [6, 36, 42]. In our study cohort, 80% of patients received 50–60 Gy. The spinal cord group, however, was likely to receive a lower radiation dose (< 50 Gy), probably due to a spinal cord tolerance dose of < 50 Gy, and to avoid potential adverse effects such as bone marrow suppression in the long lesions. As for the prognostic impact of RT, survival benefit was demonstrated when we used ≥ 50 Gy for patients of our study.

Prognostic factors

The treatment outcomes of our series are mostly consistent with those of previous reports (Additional file 2: Table S2). To date, several prognostic factors of DMGs have been suggested (Additional file 2: Table S2). Clinical factors such as age, sex, tumor location, tumor size, EOR and radiation have been considered in some reports [6, 13,14,15,16, 23,24,25, 28, 37, 42,43,44, 53, 56, 62]. As for pathological and molecular factors, there has been previous discussion of histological grading, Ki-67 labelling index, histone H3 subtype and mutations of EZH2,TP53, ATRX, TERT promoter, BRAF and FGFR1 [3, 6, 9, 13,14,15,16, 23,24,25, 28, 37, 42,43,44, 53, 56, 62]. As for tumor locations, brainstem location is reportedly a poor prognostic factor [16, 62], but in this cohort, there was no significant difference in OS between the four tumor location groups. Adulthood has also been reported as a good prognostic factor [43, 44, 54], but in this cohort, there was no significant difference in OS between adults and infants. As for sex, it was not previously reported to be a prognostic factor, but we found female sex to be an independent factor in good prognosis. Meanwhile, for pathological findings, no significant difference was found among WHO grade 2,3,4 for prognosis [62], and we obtained similar results in this study as well. As for molecular factors, EZH2 expression, TP53 mutation, ATRX expression, are reportedly poor prognostic factors and FGFR1 mutation is reportedly a good prognostic factor [24, 43, 56], but we found no significant difference in OS between TP53 mutations in our cohort. We did not investigate EZH2 and ATRX expression in this cohort. RT is reportedly a good prognostic factor [44, 56], and similarly we found RT ≥ 50 Gy to be a good prognostic factor in this cohort.

As for the prognostic impact of each factor, however, consistent results cannot be achieved universally through studies; the limited number of study patients could partly explain the absence of statistical power to detect differences between groups. In our series, there was no statistically significant difference in OS according to age, location, resection, histological grading or genetic status (Table 3). On the other hand, our multivariate analysis identified female sex and preoperative KPS score ≥ 80 as independent prognostic factors (Table 3). Further investigation in a larger cohort could contribute to a better understanding of the prognostication of DMGs.

Summary of the present study and future challenges

Complete resection of DMGs without inducing new neurological deficits is challenging. In this study, no significant difference in OS was observed based on the resection rate, but a significant difference in OS was found based on the radiation dose. It is considered crucial to complete radiation therapy without compromising KPS through surgery as a treatment. We identified no significant prolonging of OS in cases with FGFR1 mutations, but the development of local treatment with molecular targeted drugs is desired.

Limitations

Owing to the multi-institutional retrospective cohort design, this study has several limitations. Unlike in a randomized study, there could be selection bias regarding the distribution of tumor locations and decision-making of treatment strategy. The limited number of patients could explain the lack of statistical power to detect differences between groups. Attending physicians may decide to deliver treatments with consideration of the patients’ age, conditions and wishes, and thus patient selection could affect the survival findings. Variation of treatment regimen at multiple institutions, such as radiation protocol and dose schedule, should also be considered. The modest prognostic impact of clinical and molecular characteristics might be partly due to the limited population.

Our Kansai classification has limitations. The ambiguity of the current midline terminology in DMG allowed us to discriminate between the midline and non-midline structures for definition of DMG. However, it is challenging to determine the location of the origin of DMG. Some tumors which appear centered in the hemispheres have involvement of midline structures. There is the possibility, for example, of a tumor starting in the midline, but from which cells that migrated outward ultimately formed the most aggressive-appearing regions according to images. Any diffuse glioma with H3 K27M mutation would qualify for the diagnosis of DMG. Further studies could help to clarify this problem. It would nonetheless be better to consider that the Kansai classification is our approach in this study for better understanding of the pathology of DMG.

There are also limitations in this study regarding the discrimination between the midline and non-midline structures for definition of DMG. In our Kansai classification, the basal ganglia and corpus callosum were categorized as non-midline structures and were excluded from the analysis of this study, although tumors located at the basal ganglia or corpus callosum but mainly involving midline structures such as the thalamus or brainstem were categorized as midline tumors (Table 1). In the notion that any diffuse glioma with H3 K27M mutation would qualify for the diagnosis of DMG, the current midline terminology in DMG would not be necessary. Further studies of diffuse non-midline gliomas including the basal ganglia and corpus callosum tumors could help to clarify this problem.

Conclusions

Considering the term “midline” areas, which had been confused in previous reports, we classified four midline locations based on previous reports and anatomical findings in this study, and reported characteristics and outcomes of patients with histone H3 K27M-mutant DMG in the Kansai Network. This community-based study is suggested to be representative of the present status of real-world practice. Further investigation in a larger patient population could contribute to better understanding of the pathology of DMG.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACNU:

-

Nimustine hydrochloride

- ATRX:

-

Alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation, X-linked

- BEV:

-

Bevacizumab

- BRAF:

-

V-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CNS:

-

Central Nervous System

- CNS WHO 2021:

-

The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System

- DMG:

-

Diffuse midline glioma

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EOR:

-

Extent of surgical resection

- EZH2:

-

Enhancer of zeste homolog2

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery

- FGFR1:

-

Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- Gd:

-

Gadolinium

- GTR:

-

Gross total resection

- Gy:

-

Gray

- HGG:

-

High grade glioma

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IDH:

-

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

- Kansai Network:

-

Kansai Molecular Diagnosis Network for CNS Tumors

- KPS:

-

Karnofsky performance status

- LGG:

-

Low grade glioma

- Met:

-

Methylated

- MGMT:

-

O-6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase

- mOS:

-

Median overall survival

- Mut:

-

Mutated

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PR:

-

Partial resection

- PFS:

-

Progression free survival

- RT:

-

Radiation, Radiotherapy

- STR:

-

Subtotal resection

- TERT:

-

Telomerase reverse transcriptase

- TMZ:

-

Temozolomide

- TP53:

-

Tumor protein p53

References

Aboian MS, Solomon DA, Felton E, Mabray MC, Villanueva-Meyer JE, Mueller S et al (2017) Imaging characteristics of pediatric diffuse midline gliomas with histone H3 K27M mutation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38:795–800. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A5076

Aboian MS, Tong E, Solomon DA, Kline C, Gautam A, Vardapetyan A et al (2019) Diffusion characteristics of pediatric diffuse midline gliomas with histone H3–K27M mutation using apparent diffusion coefficient histogram analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 40:1804–1810. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6302

Alvi AM, Ida CM, Paolini MA, Kerezoudis P, Meyer J, Fritcher EGB et al (2019) Spinal cord high-grade infiltrating gliomas in adults: clinico-pathological and molecular evaluation. Mod Pathol 32(9):1236–1243. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0271-3

Arita H, Matsushita Y, Machida R, Yamasaki K, Hata N, Ohno M et al (2016) TERT promoter mutation confers favorable prognosis regardless of 1p/19q status in adult diffuse gliomas with IDH1/2 mutations. Acta Neuropathol Commun 8:201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-01078-2

Auffret L, Ajlil Y, Tauziede-Espariat A, Kergrohen T, Puiseux C, Riffaud L et al (2024) A new subtype of diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27 and BRAF/FGFR1 co-altered: a clinoco-radiological and histomolecular characterization. Acta Neuropathol 147:2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-023-02651-4

Bin-Alamer O, Jimenez AE, Azad TD, Bettegowda C, Mukherjee D et al (2022) H3K27M-altered diffuse midline gliomas among adult patients: A systematic review of clinical features and survival analysis. World Neurosurg 165:e251-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.06.020

Bozkurt SU, Dagcinar A, Tanrikulu B, Comunoglu N, Meydan BC, Ozek M et al (2018) Significance of H3K27M mutation with specific histomorphological features and associated molecular alternations in pediatric high-grade glial tumors. Childs Nerv Syst 34:107–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3633-5

Carrano A, Juarez JJ, Incontri D, Ibarra A, Cazares HG (2021) Sex-specific differences in glioblastoma. Cells 10:1783. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10071783

Castel D, Philippe C, Calmon R, Dret LL, Truffaux N, Boddaert N et al (2015) Histone H3F3A and HIST1H3B K27M mutations define two subgroups of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas with different prognosis and phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol 130:815–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1478-0

Chai RC, Zhang YW, Liu YQ, Chang YZ, Pang B, Jiang T et al (2020) The molecular characteristics of spinal cord gliomas with or without H3 K27M mutation. Acta Neuropathol Commun 8:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-00913-w

Chia N, Wong A, Teo K, Tan AP, Vellayappan BA, Yeo TT et al (2021) H3K27M-mutant, hemispheric diffuse glioma in an adult patient with prolonged survival. Neuro Oncol Adv 3(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdab135

Cohen KJ, Heideman RL, Zhou T, Holmes EJ, Lavey RS, Bouffet E et al (2011) Temozolomide in the treatment of children with newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic gliomas: a report from the children’s oncology group. Neuro Oncol 13(4):410–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noq205

Dono A, Takayasu T, Ballester LY, Esquenazi Y (2020) Adult diffuse midline gliomas: clinical, radiological, and genetic characteristics. J Clin Neurosci 82:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.10.005

Ebrahimi A, Skardelly M, Schuhmann MU, Ebinger M, Reuss D, Neumann M et al (2019) High frequency of H3 K27M mutations in adult midline gliomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 145:839–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-02836-5

Enomoto T, Aoki M, Hamasaki M, Abe H, Nonaka M, Inoue T et al (2020) Midline glioma in adults: clinicopathological, genetic, and epigenetic analysis. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 60:136–146. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.oa.2019-0168

Feng J, Hao S, Pan C, Wang Y, Wu Z, Zhang J et al (2015) The H3.3 K27M mutation results in a poorer prognosis in brainstem gliomas than thalamic gliomas in adults. Human Pathol 46:1626–1632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2015.07.002

Funata N, Nobusawa S, Nakata S, Yamazaki T, Takabagake K, Koike T et al (2018) A case report of adult cerebellar high-grade glioma with H3.1 K27M mutation: a rare example of an H3 K27M mutant cerebellar tumor. Brain Tumor Pathol 35:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-017-0305-9

Gilbert AR, Zaky W, Gokden M, Fuller CE, Ocal E, Leeds NE et al (2018) Extending the neuroanatomic territory of diffuse midline glioma, K27M mutant: pineal region origin. Pediatr Neourosurg 53:59–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481513

Gutierrez DR, Jones C, Varlet P, Mackay A, Warren D, Warmuth-Metz M et al (2020) Radiological evaluation of newly diagnosed non-brainstem pediatric high-grade glioma in HERBY Phase II Trial. Clin Cancer Res 26(8):1856–1865. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3154

Hassan U, Latif M, Yousaf I, Anees SB, Mushtaq S, Akhtar N et al (2021) Morphological spectrum and survival analysis of diffuse midline glioma with H3K27M mutation. Cureus 13(8):e17267. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.17267

Huang T, Garcia R, Qi J, Lulla R, Horbinski C, Behdad A et al (2018) Detection of histone H3 K27M mutation and post-translational modifications in pediatric diffuse midline glioma via tissue immunohistochemistry informs diagnosis and clinical outcomes. Oncotarget 98:37112–37124. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.26430

Ishibashi K, Inoue T, Fukushima H, Watanabe Y, Iwai Y, Sakamoto H et al (2016) Pediatric thalamic glioma with H3F3A K27M mutation, which was detected before and after malignant transformation: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 32:2433–2438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-016-3161-8

Jang SW, Song SW, Kim YH, Cho YH, Hong SH, Kim JH et al (2022) Clinical features and prognosis of diffuse midline glioma: A series of 24 cases. Brain Tumor Res Treat 10(4):255–264. https://doi.org/10.14791/btrt.2022.0035

Karlowee V, Amatya VJ, Takayasu T, Takano M, Yonezawa U, Takeshima Y et al (2019) Immunostaining of increased expression of enhancer of zeste homolog 2(EZH2) in diffuse midline glioma H3K27M-Mutant patients with poor survival. Pathobiology 86:152–161. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496691

Karremann M, Gielen GH, Hoffmann M, Wiese M, Colditz N, Warmuth-Metz M et al (2018) Diffuse high-grade gliomas with H3 K27M mutations carry a dismal prognosis independent of tumor location. Neuro Oncol 20(1):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox149

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Mulcahy Levy JM (2018) H3 K27M-mutant gliomas in adults vs. children share similar histological features and adverse prognosis. Clin Neuropathol 37:53–63. https://doi.org/10.5414/NP301085

Komori T (2021) The molecular framework of pediatric-type diffuse gliomas: shifting toward the revision of the WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Brain Tumor Pathol 38:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-020-00392-w

Liu Y, Hua W, Li Z, Wu B, Liu W (2019) Clinical and molecular characteristics of thalamic gliomas: retrospective report of 26 cases. World Neurosurg 126:e1169–e1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.061

Lopez G, Bush NAO, Berger MS, Perry A, Solomon DA (2017) Diffuse non-midline glioma with H3F3A K27M mutation: a prognostic and treatment dilemma. Acta Neuropathol Commun 5:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-017-0440-x

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D et al (2021) The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23(8):1231–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab106

Maeda S, Ohka F, Okuno Y, Aoki K, Motomura K, Takeuchi K et al (2020) H3F3A mutant allele specific imbalance in an aggressive subtype of diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-mutant. Acta Neuropathol Commun 8:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-0882-4

Matsunaga K, Fukami S, Nakajima N, Ichimasu N, Kohno M (2023) Patient with diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27-altered, carrying an FGFR1 mutation who experienced thalamic hemorrhage: A case report and literature review. NMC Case Rep 10:309–314. https://doi.org/10.2176/jns-nmc.2023-0035

Meyronet D, Esteban-Mader M, Bonnet C, Joly MO, Uro-Coste E, Amiel-Benouaich A et al (2017) Characteristics of H3 K27M-mutant gliomas in adults. Neuro Oncol 19(8):1127–1134. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/now274

Ostrom QT, Kinnersley B, Wrensch MR, Eckel-Passow JE, Armstrong G, Rice T et al (2018) Sex-specific glioma genome-wide association study identifies new risk locus at 3p21.31 in females, and finds sex-differences in risk at 8q24.21. Sci Rep 8:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24580-z

Park C, Kim TM, Bae JM, Yun H, Kim JW, Choi SH et al (2021) Clinical and genomic characteristics of adult diffuse midline glioma. Cancer Res Treat 53(2):389–398. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2020.694

Peng Y, Ren Y, Huang B, Tang J, Jv Y, Mao Q et al (2023) A validated prognostic nomogram for patients with H3 K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma. Sci Rep 13:9970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37078-0

Picca A, Berzero G, Bielle F, Touat M, Savatovsky J, Polivka M et al (2018) FGFR1 actionable mutations, molecular specificities, and outcome of adult midline gliomas. Neurology 90(23):e2086–e2094. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005658

Pratt D, Natarajan SK, Banda A, Giannini C, Vats P, Koschmann C et al (2018) Circumscribed/non-diffuse histology confers a better prognosis in H3K27M-mutant gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 135:299–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1805-3

Qiu T, Chanchotisatien A, Qin Z, Wu J, Du Z, Zhang X et al (2020) Imaging characteristics of adult H3 K27M-mutant gliomas. J Neurosurg 133:1662–1670. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.9.JNS191920

Rocca GL, Sabatino G, Altieri R, Signorelli F, Ricciardi L, Gessi M et al (2019) Significance of H3K27M mutation in “Nonmidline” high-grade gliomas of cerebral hemispheres. World Neurosurg 131:174–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.08.024

Sasaki T, Fukai J, Kodama Y, Hirose T, Okita Y, Moriuchi S et al (2018) Characteristics and outcomes of elderly patients with diffuse gliomas: a multi-institutional cohort study by Kansai Molecular Diagnosis Network for CNS Tumors. J Neurooncol 140:329–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2957-7

Schreck KC, Ranjan S, Skorupan N, Bettegowda C, Eberhart CG, Ames HM et al (2019) Incidence and clinicopathologic features of H3 K27M mutations in adults with radiographically-determined midline gliomas. J Neurooncol 143:87–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03134-x

Schuller U, Iglauer P, Dorostkar MM, Mawrin C, Herms L et al (2021) Mutations within FGFR1 are associated with superior outcome in a series of 83 diffuse midline gliomas with H3F3A K27M mutations. Acta Neuropathol 141:323–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-020-02259-y

Schulte JD, Buerki RA, Lapointe S, Molinaro AM, Zhang Y, Villanueva-Meyer JE et al (2020) Clinical, radiologic, and genetic characteristics of histone H3 K27M-mutant diffuse midline gliomas in adults. Neuro Oncol Adv 2(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdaa142

Shah A, Jhawar S, Ai G, At G (2021) Corpus callosum and its connections: A fiber dissection study. World Neurosurg 151:e1024–e1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.05.047

Shi S, Lu S, Jing X, Liao J, Li Q (2021) The prognostic impact of radiotherapy in conjunction with temozolomide in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. A systemic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 148:e565-571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.01.024

Solomon DA, Wood MD, Tihan T, Bollen AW, Gupta N, Phillips JJJ et al (2016) Diffuse midline gliomas with histone H3–K27M mutation: A series of 47 cases assessing the spectrum of morphologic variation and associated genetic alterations. Brain Pathol 26:569–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12336

Stabellini N, Krebs H, Patil N, Waite K, Barnholtz-Sloan JS (2021) Sex difference in time to treat and outcomes for gliomas. Front Oncol 11:630597. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.630597

Swanson LW, Sporns O, Hahn JD (2016) Network architecture of the cerebral nuclei (basal ganglia) association and commissural connectome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 25:5972–5981. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.161318411

Thomas A (2000) Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. J Neurosci Nurs 32(5):250–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.10138

Thust S, Micallef C, Okuchi S, Brandner S, Kumar A, Mankad K et al (2021) Imaging characteristics of H3 K27M histone-mutant diffuse midline glioma in teenagers and adults. Quant Imaging Med Surg 11(1):43–56. https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-19-954

Umehara T, Arita H, Yoshioka E, Shofuda T, Kanematsu D, Kinoshita M et al (2019) Distribution differences in prognostic copy number alteration profiles in IDH-wild type glioblastoma cause survival discrepancies across cohorts. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0749-8

Vuong HG, Ngo TNM, Le HT, Dunn IF (2022) The prognostic significance of HIST1H3B/C and H3F3A K27M mutations in diffuse midline gliomas in influenced by patient age. J Neurooncol 158:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-022-04027-2

Vuong HG, Ngo TNM, Le HT, Jea A, Hrachova M, Battiste J et al (2022) Prognostic implication of patient age in H3K27M-mutant gliomas. Front Oncol 12:858148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.858148

Wang L, Li Z, Zhang M, Piao Y, Chen L, Liang H et al (2018) H3 K27M-mutant diffuse midline gliomas in different anatomical locations. Human Pathol 78:89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2018.04.015

Wang Y, Feng LL, Ji PG, Liu JH, Guo SC, Zhai YL et al (2021) Clinical feature and molecular markers on diffuse midline gliomas with H3K27M mutations: A 43 cases retrospective cohort study. Front Oncol 10:602553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.602553

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon; 2021.

Williams EA, Brastianos PK, Wakimoto H, Zolal A, Filbin MG, Cahill DP et al (2023) A comprehensive genomic study of 390 H3F3A-mutant pediatric and adult diffuse high-grade gliomas, CNS WHO grade 4. Acta Neuropathol 146:515–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-023-02609-6

Yabuno S, Kawauchi S, Umakoshi M, Uneda A, Fujii K, Ishida J et al (2021) Spinal cord diffuse midline glioma, H3K27M-mutant effectively treated with bevacizumab: A report of two cases. NMC Case Rep J 8:505–511. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmccrj.cr.2021-0033

Yoshimoto K, Hatae R, Sangatsuda Y, Suzuki SO, Hata N, Akagi Y et al (2017) Prevalance and clinicopathological features of H3.3 G34-mutant high-grade gliomas: a retrospective study of 411 consecutive glioma cases in a single institution. Brain Tumor Pathol 34:103–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-017-0287-7

Zhao JP, Liu XJ, Lin HZ, Cui CX, Yue YJ, Gao S et al (2022) MRI comparative study of diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M-altered and glioma in the midline without H3K27-altered. BMC Neurol 22:498. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-03026-0

Zheng L, Gong J, Yu T, Zou Y, Zhang M, Nie L et al (2022) Diffuse midline gliomas with histone H3 mutation in adults and children. Am J Surg Pathol 46:863–871. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001897

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all clinicians who took care of the patients and contributed to this study by providing specimens and clinical information. We thank Ms. Ai Takada and Ms. Yukako Matsuda at the Institute for Clinical Research, NHO Osaka National Hospital, Ms. Motoko Namiki at the Department of Neurological Surgery, Wakayama Medical University, and Ms. Yuki Nishikawa at the Wakayama Rosai Hospital for their excellent assistance. We acknowledge proofreading and editing by Benjamin Phillis at the Clinical Study Support Center, Wakayama Medical University.

Funding

This study was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI (No. 23K08529, JF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NH, JF, HN, HK, YO, KM, YoKa: Study design. NH, JF, HN, HK, KN, TU, KN, NK,YO, NK, NaHa, HA, KT, DS, TI, TK, YS, YM, KI, MM, TA, TaTo, MN, KH, NT, TaTs, YN, SO, NoNa, AW, AI, MU, MaKi, KaMo, NaNa: Data collection. YoKo: Pathology review. EY, DK, AK, SM, TS, MM: Sample analysis. NH, JF, HN, HK, KM, YoKa: Data analysis. NH, JF, YoKa: Interpretation. NH, JF, YoKa: Manuscript writing. KM, NaNa, YoKa: Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Osaka National Hospital (No. 713), Wakayama Medical University (No. 98), Wakayama Rosai Hospital (No. 20 Res-17), and all collaborative institutes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in association with this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Classification of "midline" or "non-midline" in the previous reports.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Summary of the previous reports on histone H3 K27-mutant diffuse midline glioma cohort studies.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Discordance between imaging features (low/high grade) and histological findings (presence or absence of GBM features) in the biopsy cases.

Additional file 4: Figure S1

. MR imaging of histone H3 K27-mutant gliomas in Kansai Network. A. a, b: FLAIR, The tumor is a sole lesion, and main location is the third ventricle: Others/midline (included). B. a, b, c: FLAIR, The tumor is comprised of contiguous multifocal lesions, and main location is the thalamus: Thalamus/midline (included). C. a: FLAIR, b:T1-Gd, The tumor is comprised of non-contiguous multifocal lesions, and the main location is the thalamus and/or corpus callosum, unclassified tumor: Others/midline (included). D. a: T1-Gd, b, c: FLAIR, The tumor is comprised of non-contiguous multifocal lesions, and the main location is unclassified, the cerebral hemisphere is more involved than the brainstem : Others/non-midline (excluded). E. a, b: FLAIR, c:T1-Gd, The tumor is comprised of contiguous multifocal lesions, and the main location is the left basal ganglia, which involve the thalamus and/or the brainstem more than the cerebral hemisphere: Others/midline (included). F. a: FLAIR, b:T1-Gd, The tumor is comprised of contiguous multifocal lesions, and the main location is the right medial temporal lobe: Cerebral hemisphere/non-midline (excluded)

Additional file 5: Figure S2

. Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to clinical factors: histopathology (LGG vs. HGG without GBM features vs. GBM features) (a), histopathology (LGG + HGG without GBM features vs. GBM features) (b), preoperative KPS score (≥ 70 vs. < 70) (c), EOR (GTR + STR vs. PR + Biopsy) (d), repeat surgical resection (e), RT+TMZ (f), TMZ (g), BEV (adjuvant + recurrent) (h), BEV (adjuvant) (i), Radiation (j), RT (≥ 50 Gy vs. < 50 Gy) (k), RT (≥ 40 Gy vs. < 40 Gy) (l).

Additional file 6: Figure S3

. (Thalamus). Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to clinical factors: age (a), sex (b), preoperative KPS score (c), extent of surgical resection (d) adjuvant treatment (e) and radiation dose (f), molecular factors: TERT (g), MGMT (h), TP53 (i), BRAF (j), FGFR1 (k) and EGFR (l) in the study cohort.

Additional file 7: Figure S4

. (Brainstem). Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to clinical factors: age (a), sex (b), preoperative KPS score (c), extent of surgical resection (d) adjuvant treatment (e) and radiation dose (f), molecular factors: TERT (g), MGMT (h), TP53 (i), BRAF (j), FGFR1 (k) and EGFR (l) in the study cohort.

Additional file 8: Figure S5

. (Spinal cord). Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to clinical factors: age (a), sex (b), preoperative KPS score (c), extent of surgical resection (d) adjuvant treatment (e) and radiation dose (f), molecular factors: TERT (g), MGMT (h), TP53 (i), BRAF (j), FGFR1 (k) and EGFR (l) in the study cohort.

Additional file 9: Figure S6

. (Other midline location). Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to clinical factors: age (a), sex (b), preoperative KPS score (c), extent of surgical resection (d) adjuvant treatment (e) and radiation dose (f), molecular factors: TERT (g), MGMT (h), TP53 (i), BRAF (j), FGFR1 (k) and EGFR (l) in the study cohort.

Additional file 10: Figure S7

. Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to radiation dose without spinal cord group: Radiation dose (a), RT (≥ 50 Gy vs. < 50 Gy) (b), RT (≥ 40 Gy vs. < 40 Gy) (c)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, N., Fukai, J., Nakatogawa, H. et al. Neuroradiological, genetic and clinical characteristics of histone H3 K27-mutant diffuse midline gliomas in the Kansai Molecular Diagnosis Network for CNS Tumors (Kansai Network): multicenter retrospective cohort. acta neuropathol commun 12, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-024-01808-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-024-01808-w