Abstract

Background Neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusions are found in 1% of gliomas across children and adults. TRK inhibitors are promising therapeutic agents for NTRK-fused gliomas because they are tissue agnostic and cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Methods We investigated twelve NGS-verified NTRK-fused gliomas from a single institute, Seoul National University Hospital. Results The patient cohort included six children (aged 1–15 years) and six adults (aged 27–72 years). NTRK2 fusions were found in ten cerebral diffuse low-grade and high-grade gliomas (DLGGs and DHGGs, respectively), and NTRK1 fusions were found in one cerebral desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma and one spinal DHGG. In this series, the fusion partners of NTRK2 were HOOK3, KIF5A, GKAP1, LHFPL3, SLMAP, ZBTB43, SPECC1L, FKBP15, KANK1, and BCR, while the NTRK1 fusion partners were TPR and TPM3. DLGGs tended to harbour only an NTRK fusion, while DHGGs exhibited further genetic alterations, such as TERT promoter/TP53/PTEN mutation, CDKN2A/2B homozygous deletion, PDGFRA/KIT/MDM4/AKT3 amplification, or multiple chromosomal copy number aberrations. Four patients received adjuvant TRK inhibitor therapy (larotrectinib, repotrectinib, or entrectinib), among which three also received chemotherapy (n = 2) or proton therapy (n = 1). The treatment outcomes for patients receiving TRK inhibitors varied: one child who received larotrectinib for residual DLGG maintained stable disease. In contrast, another child with DHGG in the spinal cord experienced multiple instances of tumour recurrence. Despite treatment with larotrectinib, ultimately, the child died as a result of tumour progression. An adult patient with glioblastoma (GBM) treated with entrectinib also experienced tumour progression and eventually died. However, there was a successful outcome for a paediatric patient with DHGG who, after a second gross total tumour removal followed by repotrectinib treatment, showed no evidence of disease. This patient had previously experienced relapse after the initial surgery and underwent autologous peripheral blood stem cell therapy with carboplatin/thiotepa and proton therapy. Conclusions Our study clarifies the distinct differences in the pathology and TRK inhibitor response between LGG and HGG with NTRK fusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase (NTRK) family gene fusions are rare, found in only 1% of gliomas across adult and paediatric patients. Despite the rarity of these fusions, TRK inhibitors are emerging as promising therapeutic options. This promise stems from their broad efficacy across various cancer types of any organ, their ability to cross the blood‒brain barrier (BBB) effectively, and the ongoing improvement of second-generation inhibitors designed to overcome resistance [7, 16, 22, 32].

TRK inhibitors represent a targeted strategy for cancer therapy designed to block the activity of NTRK fusion proteins. These fusion proteins are formed when the NTRK family genes NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 fuse with other genes, leading to abnormal activation of signalling pathways that promote cancer cell growth and survival [10]. TRK inhibitors achieve these effects by binding to the ATP binding site of NTRK fusion proteins, preventing the phosphorylation of downstream signalling molecules and blocking the transmission of growth signals within cancer cells (Table 1) [16]. The mechanistic basis of TRK inhibitors lies in their disruption of signalling pathways responsible for driving cancer cell proliferation and survival, ultimately leading to tumour regression or tumour growth inhibition [33].

In 2018, larotrectinib became the initial TRK inhibitor to gain FDA approval, demonstrating selective inhibition of TRK A/B/C across various solid tumours, including gliomas [8]. Notably, larotrectinib exhibited good tolerance in paediatric patients, with minimal adverse effects such as mild vomiting and fever. Subsequently, in 2019, entrectinib received FDA approval for TRK A/B/C inhibition in NTRK-fused solid tumours and ROS1-positive nonsmall cell lung cnancer (NSCLC) [5]. However, resistance to larotrectinib and entrectinib has emerged, as has been the case for other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, leading to FDA approval of the first second-generation TRK inhibitor, repotrectinib, in 2023 [9], however, in other solid cancer types, it is currently undergoing clinical trials (TPX-0005).

Despite the increasing interest in TRK inhibitors, the diagnosis of tumours with NTRK fusions presents numerous challenges. Due to the rarity of NTRK fusions in all cancers, routine next-generation sequencing (NGS) is impractical for all solid tumours [10]. The use of alternative molecular testing methods such as direct sequencing or in situ hybridization is not recommended because of the diversity of NTRK fusions observed in various central nervous system (CNS) tumours, with NTRK1/2/3 interacting with multiple fusion partners [10]. Pan-TRK immunohistochemistry (IHC) using antibodies such as EPR17341 (Ventana, ready to use, Export, US) and A7H6R (Cell Signaling, 1:50, Massachusetts, US) is available but has exhibited inconsistent reliability as a screening tool for NTRK fusions [2, 25]. Until pan-TRK IHC is adequately optimized to serve as a surrogate marker for NTRK fusion, NGS remains the most precise method for confirming the diagnosis of NTRK-fused tumours. This approach is the foundation for the evidence-based administration of TRK inhibitors.

There is a compelling rationale to continue pursuing efficient and effective diagnostic methods for NTRK-fused tumours, particularly for CNS tumours. The BBB has historically been an obstacle to successful pharmacotherapy for CNS tumours. Therefore, it is essential to explore molecules with the ability to effectively penetrate the BBB, maximally extending their utility. The ability of TRK inhibitors to cross the BBB provides a primary incentive to optimize the detection of NTRK-fused CNS tumours [5, 8]. Second, both neuropathologists and oncologists emphasize the effectiveness of TRK inhibitors against solid tumours that have metastasized to the brain [8].

For patients with high-grade gliomas (HGGs), the standard treatment approach, which includes a combination of surgery, concurrent chemoradiation therapy and Temozolomide (CCRT-TMZ), still results in a poor prognosis. This consideration has prompted the exploration of alternative therapeutic options [30]. For paediatric glioma patients, the urgent need for a targeted therapy is increased because radiation therapy carries the inherent risks of the development of secondary glioma, meningioma, or sarcoma and radiotoxicity to the developing and growing brain [3, 13]. This study was designed to investigate the real-world applications of the diagnostic and therapeutic options for NTRK-fused gliomas in both paediatric and adult patients.

Materials and methods

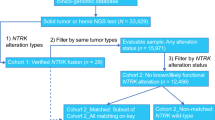

Between 2018 and January 2024, twelve patients with confirmed NTRK-fused gliomas were identified at Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH). Since the establishment of the NGS platform and brain tumour-targeted gene panel in the Department of Pathology at SNUH in 2018, nearly all primary CNS tumours have been subjected to NGS. Since the initiation of this NGS program, twelve cases have been discovered, including two recurrent cases. The initial tumours in two specific patients developed in 1998 and 2017. In this study, the clinicopathological characteristics of the twelve patients with NTRK-fused CNS tumours were reviewed, highlighting the sex and age distributions of the patients (Tables 2 and 3). The paediatric patients showed a significant female predominance, with a male:female ratio of 1:5 and a median age of 3 years (range, 1–15 years). In contrast, the adult patients exhibited a male predominance, with a male:female ratio of 4:2 and a median age of 64 years (range, 27–72 years). Overall, the female:male ratio was 7:5. In terms of tumour grade, LGGs were more common among female patients (female:male ratio of 5:1) and paediatric patients (child:adult ratio of 4:2), while HGGs were more prevalent among male patients (male:female ratio of 4:2) and adult patients (child:adult ratio of 2:4).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Neutral formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues were sliced into 3 μm thick sections for H&E staining and IHC. For pan-TRK IHC, two different clones were used for each tumour. The pan-TRK assays with EPR17341 (Ventana, ready to use, Export, US) and A7H6R (Cell Signaling, 1:50, Massachusetts, US) were performed using a standard avidin–biotin-peroxidase method with the BenchMark ULTRA procedure (Roche Diagnostics). For the pan-TRK assay with the Cell Signaling antibody (clone A7H6R), the vendor-recommended immunoprecipitation antibody dilution of 1:50 was used, with antigen retrieval for 64 min and antibody incubation for 60 min. Tumours were classified as positive for TRK if more than 1% of the tumour cells exhibited staining at any intensity above the background intensity, regardless of the subcellular staining pattern (cytoplasmic, membranous, nuclear, or perinuclear). However, in TRK-positive tumours, the staining was consistently diffuse and robustly positive, observed in more than 90% of the cells [11]. For diagnosis, several immunohistochemical analyses were conducted on tumour sections using the following antibodies (Supplementary Table 1): anti-IDH1 R132H (H09) monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution, Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), anti-ATRX polyclonal antibody HPA001906 (1:300 dilution, Atlas Antibodies AB, Bromma, Sweden), anti-p53 monoclonal antibody, DO-7 code M7001 (1:1000 dilution, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-pHH3 antibody (1:100 dilution, Cell Marque, Rocklin, USA), and anti-Ki67 antibody (1:1000 dilution, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). The Ki-67 labelling index was calculated using the Sectra Ki-67 morphometric analyser on virtual Leica Biosystems slides. We used known positive tissues or internal positive controls as IHC-positive controls; for the negative controls, the primary antibodies were omitted during IHC.

NGS and pipelines for the analysis of somatic mutations

NGS analyses were performed with tumour DNA extracted from FFPE tumour tissues and the NEXTSeq 550Dx system using a tailored panel called “FiRST Brain Tumour DNA/RNA panel v3.3”, which was developed in-house at SNUH, as previously reported by our research team [20]. The panel comprises 223 brain tumour-associated genes and 151 fusion genes, including NTRK1/2/3. The fusion genes were sequenced using RNA methods. Somatic mutations were detected using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) Mutect2 v4.1.4.1. tool with the default parameters. To avoid germline variant contamination, we used the gnomad.hg19.vcf Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) and 1000 g_pon.hg19.vcf files, which included a normal panel for 1000 genomes. The files were provided by the GATK resource bundle. After somatic mutations were called, all variants were annotated with ANNOVAR (https://doc-openbio.readthedocs.io/projects/annovar/en/latest/) as previously described [20].

Results

Histopathology of NTRK-fused gliomas

NTRK-fused gliomas can be categorized as DLGGs or DHGGs based on the mitotic rate, microvascular proliferation (MVP) status, and necrosis status (Supplementary Table 2). The Ki-67 labelling index was used as a reference.

Diffuse low-grade gliomas (DLGGs)

In this cohort, the majority of DLGGs with NTRK fusions exhibited diffusely infiltrating astrocytic tumours characterized by low mitotic activity (< 3/10 high-power fields (HPFs)) and a low Ki-67 labelling index (< 3%). These tumours lacked HG features, such as MVP and necrosis. However, three cases displayed distinctive features that were morphologically similar to those of myxoid glioneuronal tumour (MGNT) of the lateral ventricle, desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma (DIG), and astrocytoma with neuropil-like islands, as described in the 2016 4th edition of the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System (hereafter referred to as the WHO2016).

A tumour with the KIF5A::NTRK2 fusion that developed in the right lateral and 3rd ventricles of patient #2 (15 y/F) exhibited features of a LG MGNT (Fig. 1).

A, B Patient #2 (15 y/F) presented with an intraventricular diffuse low-grade glioma located at the lateral ventricle, exhibiting heterogeneous high signal intensity on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted and T1-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. B The tissue in the H&E section resembled a myxoid glioneuronal tumour, characterized by monotonous round cells within a myxoid background. D, F Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positivity for GFAP, TRK, and Olig2 in this tumour. G An Arriba plot generated from next-generation sequencing (NGS) data using RNA identified the KIF5A::NTRK2 in-frame fusion in the tumour (C, D: H&E, E: GFAP, F: Olig2; scale bar, C-E: 200 μm, F: 100 μm)

A tumour with the TPR::NTRK1 fusion that developed in the left temporo-occipital lobe of patient #4 (1 y/F) exhibited microscopic features compatible with DIG, CNS WHO grade 1. This patient is a long-term survivor with no evidence of tumour (NET) for 25 years following gross total resection. The tumour exhibited storiform spindled astrocytic tumour cells and ganglion cells, fitting the profile for DIG.

A tumour with the LHFPL2::NTRK2 fusion in the left temporal lobe of patient #5 (27 y/F) had features of anaplastic astrocytoma with neuropil-like islands, on the basis of the diagnostic criteria of the WHO2016 classification. The neuropil-like islands were positive for synaptophysin but negative for GFAP (Fig. 2). This tumour had a moderately high mitotic rate (4/10 HPFs) but a low Ki-67 index (1.2%).

Patient #5, a 27-year-old female, presented with an uncommon glioma harbouring the LHFPL3::NTRK2 fusion. A, B T1 and T2 FLAIR MR images revealed a 5.3 × 4.5 × 1.6 cm solid and cystic mass in the right lateral ventricle with multifocal enhancement in the right intra- and periventricular white matter. C, D H&E sections of the tumour exhibited a distinctive pathology characterized by multiple whorls formed by glial cells and neuropil-like islands. E The spindle-shaped glial cells forming the whorls were positive for GFAP and negative for synaptophysin, but F the neuropil-like islands were positive for synaptophysin and negative for GFAP. G An Arriba plot generated from next-generation sequencing (NGS) data for tumour RNA identified the LHFPL3::NTRK2 in-frame fusion (scale bar, C–E: 200 μm, F: 100 μm)

Diffuse high-grade gliomas (DHGGs)

The histopathological characteristics of four adult HGGs (patients #9-#12) with SPECC1L::NTRK2, FKBP15::NTRK2, KANK1::NTRK2, and BCR::NTRK2 fusions and a paediatric HGG with the ZBTB43::NTRK2 fusion (patient #7, 2 y/F) were consistent with IDH wild-type (IDH-wt) GBM. These tumours displayed high mitotic activity, high Ki-67 proliferation indices, MVP, and necrosis, meeting the criteria for CNS WHO grade 4 tumours.

A spinal cord tumour with the TPM3::NTRK1 fusion (patient #8, 2y/F) also exhibited a GBM-like pathology with MVP and necrosis.

One GBM, IDH-wt with the BCR::NTRK2 fusion, in patient #12 (54 y/M) contained uniform round cells with a clear cytoplasm, resembling those of oligodendroglioma. This tumour also harboured additional genetic abnormalities, including TERT promoter (C228T) mutation, PTEN mutation, and homozygous CDKN2A/2B deletion (Fig. 3).

Patient #12 had the BCR::NTRK2 fusion. A, B T2-weighted turbo spin‒echo (TSE) and T2 FLAIR images showing a hyperintense mass in the thalamus and bifrontal area with peritumoral oedema. C The tumour was composed of oligodendroglioma-like clear cells with microvascular proliferation and pseudopalisading necrosis. D and E Diffuse positivity for TRK and Olig2 was observed in the cytoplasm and nuclei, respectively, of tumour cells. F The Ki-67 labelling index was high (88.4%). G The Arriba plot revealed the in-frame fusion between the BCR gene and NTRK2 gene (scale bar, F: 50 μm)

This categorization scheme emphasizes the differences in histological features and molecular profiles between LGG and HGG in patients with NTRK-fused gliomas.

In the NTRK-fused CNS tumours in our patients, pan-TRK IHC using clone A7H6R and clone EPR17341 revealed diffuse cytoplasmic positivity with sparing of nuclei in nearly 100% of the tumour cells across all cases. Clone EPR17341 displayed slightly less intense staining than clone A7H6R, but both clones showed good concordance with the NTRK fusion.

Genetic abnormalities of NTRK-fused gliomas

Except for the DIG of patient #4 (1 y/F) and the spinal HGG of patient #6 (2 y/F), both of which had NTRK1 fusions, all other cerebral gliomas had NTRK2 fusions. The fusion partners of NTRK2 included HOOK3, KIF5A, GKAP1, LHFPL3, SLMAP, ZBTB43, SPECC1L, FKBP15, KANK1, and BCR, while the NTRK1 fusion partners were TPR and TPM3 (Table 4).

Diffuse low-grade gliomas (DLGGs)

All LGGs exclusively harboured NTRK fusions without additional genetic alterations.

Diffuse high-grade gliomas (DHGGs)

The HGGs, including the GBMs in the adult patients and a spinal HGG in a paediatric patient, exhibited additional genetic alterations. The genetics of IHG in patient #7 was relatively simple and had hemizygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B in addition to ZBTB43::NTRK2 fusion.

In the remaining tumours, additional genetic alterations included homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B in five patients (#8-12), TERT promoter (C228T) mutation in two patients (#11 and #12), PDGFRA/KIT/MDM4/AKT3 amplification in patient #10, and mutations in TP53 (p.Glu286Ala, c.857A > C; p.Glu224Asp, c.672G > T) and PTEN (p.Ile101Thr, c.302 T > C; p.Lys6fs, c.17_18delAA) as well as multiple chromosomal losses and trisomy 7 in patient #11 (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

Illustration of the clinicopathological and genetic abnormalities in NTRK-fused gliomas in paediatric and adult patients, Abbreviations LG, low-grade; HG, high-grade; P, parietal lobe; LV, lateral ventricle; Thal, thalamus, TO, temporo-occipital lobe; T, temporal lobe; FT, fronto-temporal lobe; SP, spinal cord; CBLL, cerebellum; F/Thal, frontal lobe and thalamus; Hemi D, hemizygous deletion; HoD, homozygous deletion

Treatment and response to TRK inhibitor therapy in patients with NTRK-fused gliomas

Four patients with LGG who underwent complete resection (patients #1, 2, 5, and 6) did not undergo adjuvant treatment. The patients had NET throughout their follow-up periods. However, one patient with residual tumour who was diagnosed with LGG (patient #3) and three patients with HGG (patients #5, #6, and #9) received TRK inhibitor therapy at different stages of disease management. The patients with NTRK-fused gliomas exhibited responses to TRK inhibitor therapy, though the durability of these responses varied among the patients (Fig. 5).

Summary of the radiological characteristics and treatment timelines for patients receiving TRK inhibitor therapy (IHG: Infant-type hemispheric glioma, DLGG: Diffuse low-grade glioma, DHGG: Diffuse high-grade glioma, GBM: Glioblastoma, IDH-Wild-type, OP: Operation, SD: Stable disease, PD: Progressive disease, NET: No evidence of tumour, aPBSCT: autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; Carbo, carboplatin, Thio, thioflavin #3)

Patient #3, a 3-year-old female with GKAP1::NTRK2-fused LGG in the right thalamus and 3rd ventricle, underwent adjuvant larotrectinib treatment for residual tumour. During the 14-month follow-up period, MRI scans revealed stable disease. Larotrectinib treatment is ongoing and planned to be continued for an additional 10 months.

Patient #7, a 2-year-old female who was diagnosed with IHG with the ZBTB43::NTRK2 fusion and hemizygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B, underwent induction chemotherapy, autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (aPBSCT) with carboplatin and thiotepa, and proton therapy (55.8 Gy) following the initial surgical removal of her left frontotemporal tumour (Fig. 5). After the second surgery to remove the residual tumour, she was enrolled in an oral repotrectinib clinical trial. Throughout the 3-year follow-up period after repotrectinib treatment, this patient demonstrated NET. However, the final outcome of this patient is unknown, as the clinical trial has not yet been completed.

Patient #8, a 3-year-old girl who was previously healthy, presented at the clinic with sudden lower extremity weakness for the previous two weeks. Initial MRI of the spine revealed a tumour at the C7 to L1 level (Fig. 5). Following laminectomy and tumour removal, the patient was diagnosed with a spinal GBM, IDH-wt, by the 2016 WHO criteria. Within one month after the operation, the patient developed gait disturbance and constipation. Only four months after the initial operation and following two cycles of CCRT-TMZ, a second laminectomy and intramedullary removal of the residual tumour were conducted (Fig. 5). After pathological confirmation of the recurrence as a spinal GBM-like HGG, four cycles of procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) chemotherapy were administered. As the tumour recurred again during follow-up, a third operation was conducted. During this procedure, SNUH utilized NGS with a brain tumour-targeted gene panel, identifying the TPM3::NTRK1 fusion, amplification of MDM4/AKT3, and one-copy loss of PTEN/FGFR2, leading to the diagnosis of the tumour as HGG, not otherwise specified (NOS), according to the WHO2021 criteria. Subsequent recurrences warranted a fourth operation, and after the fifth recurrence, a decision was made to enrol the patient in a clinical trial for larotrectinib. She was resistant to the offered chemotherapies and had stable disease with larotrectinib. However, the patient passed away due to disease progression 22 months after the initial trial of larotrectinib.

Patient #9, a 64-year-old male with SPECC1L::NTRK2-fused HGG with additional homozygous deletion of CDKN2A, underwent adjuvant CCRT-TMZ only. Despite ependymal enhancement, the condition of patient #9 remained relatively stable without gait disturbance during the 27-month follow-up.

Patient #10, a 67-year-old male with FKBP15::NTRK2-fused HGG of the cerebellum, had additional PDGFRA/KIT amplification, homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B and 1-copy loss of PTEN/NF1. He received entrectinib after completing CCRT-TMZ#6 and re-radiation therapy (45 Gy). The tumour showed transiently stable disease on entrectinib for 2 months, but the patient eventually experienced disease progression and death in three months after starting entrectinib (Table 3 and Fig. 5).

Patients #11 and #12 did not undergo additional treatment after surgery. Patient #11, a 72-year-old male with the KANT::TRAK2 fusion and the associated histopathological characteristics, along with additional genetic abnormalities – homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B, mutation of PTEN/TP53, TERTp mutation (C228T), PTEN loss, trisomy 7, and losses of 10, 14q, 22q, indicative of HGG – was in compromised general health and died 4 months after surgery.

Patient #12, a 54-year-old male diagnosed with glioblastoma (GBM) with the BCR::NTRK2 fusion, PTEN mutation, homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B, and TERTp mutation (C228T), refused adjuvant therapy and received palliative care, resulting in death 13 months post-surgery.

Discussion

The development and evolution of first-generation TRK inhibitors and the subsequent development of second-generation TRK inhibitors represent significant milestones in precision oncology [29]. First-generation TRK inhibitors were initially developed following the discovery of NTRK family gene fusions across diverse cancers. Their development process included rigorous preclinical studies confirming their efficacy against NTRK fusion proteins [7]. Their efficacy and safety were evaluated in subsequent clinical trials, resulting in their regulatory approval [6, 15, 24, 29]. First-generation TRK inhibitors, such as larotrectinib and entrectinib, effectively block downstream signalling pathways, resulting in durable responses and favourable tolerability, as observed in clinical trials [15]. Both larotrectinib and entrectinib function as TRK inhibitors by targeting the ATP binding site of NTRK family genes. Additionally, entrectinib has a broader spectrum of activity than other first-generation TRK inhibitors, also targeting ROS1 and ALK fusion genes through the same binding mechanism. Drugs acting through both mechanisms have shown high response rates in clinical trials; however, some patients have developed resistance to these drugs over time [29]. The development of second-generation TRK inhibitors, such as repotrectinib, aimed to overcome these resistance mechanisms and provide therapeutic options for patients who experience relapse or develop resistance to first-generation TRK inhibitors. Repotrectinib targets multiple kinases, including NTRK, ROS1, and ALK [24]. Second-generation NTRK inhibitors utilize an allosteric binding site other than the ATP binding site and thus interact with regions outside the ATP binding site to regulate TRK fusion activity. This method increases their selectivity for TRK fusion proteins, minimizing off-target effects and reducing the risk of adverse reactions [24]. Other second-generation TRK inhibitors, such as selitrectinib and taletrectinib, have shown increased efficacy in patients who have experienced progression on first-line therapies or who have developed resistance mutations. Clinical trials for these drugs are currently in progress, aiming to further explore their potential for overcoming resistance to targeted therapy [29].

The primary recognized adverse effects of TRK inhibitors are constitutional symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, liver toxicity, peripheral oedema, rash, cardiac toxicity, and neurological effects such as dizziness, headache, or peripheral neuropathy [26, 27]. Despite these adverse effects, TRK inhibitors are generally well tolerated by patients.

Among the twelve patients diagnosed with CNS gliomas harbouring NTRK fusions, four received TRK inhibitors; three of these were paediatric patients, and one was an adult patient. The choice of TRK inhibitor for each patient was determined solely by the clinical trials in which they were enrolled. One adult patient (#10) received entrectinib after completing CCRT with six cycles of TMZ. The patient initially had stable disease for 2 months; however, no significant therapeutic benefit was observed. Disease progression occurred, and the patient eventually died 3 months after starting entrectinib treatment.

The question of whether initiating a TRK inhibitor as the first-line adjuvant chemotherapy is equivalent to or beneficial compared to the conventional CCRT-TMZ#6 (6 treatment cycles) Stupp protocol remains unanswered [19]. Particularly in paediatric patients, the use of a CCRT-TMZ#6 adjuvant regimen, which is the standard approach for managing HGG in adults, requires careful consideration. This approach has significant concerns due to its high toxicity, the potential for the development of secondary tumours in response to radiation therapy, and its adverse effects on development and growth [23]. Considering these concerns, paediatric patients with CNS tumours are ideal candidates for treatment with a TRK inhibitor as first-line adjuvant chemotherapy. The relatively mild toxicity profile associated with targeted therapies makes this approach an attractive option for paediatric patients. For instance, patient #3 (3 y/F) received larotrectinib for residual DLGG after surgery. During her 10-month evaluation period, she maintained stable disease, with a progression-free survival (PFS) time of at least 10 months.

Patient #7 (2 y/F), who was diagnosed with ZBTB43::NTRK2-fused HGG, underwent induction chemotherapy, aPBSCT with carboplatin and thiotepa, and proton therapy (55.8 Gy) after her first surgery. Unfortunately, due to tumour progression, a second surgical intervention was performed. Following the second gross total removal of the tumour, she started treatment with repotrectinib. Remarkably, after completing the repotrectinib regimen, there was no evidence of tumour recurrence for 3 years. This exceptional response in a HG IHG highlights the prominent potential of targeted TRK inhibitor therapy in such challenging cases. However, the exact outcome of this patient remains undetermined, as the clinical trial in which she is enrolled is ongoing. Relative to the other patients, this patient had only hemizygous deletion of CDKN2A/2B as an additional genetic alteration, which is thought to have contributed to her relatively good prognosis.

Importantly, 40% of nonbrainstem HGGs in children less than 3 years old have been reported to harbour an NTRK fusion [31]. This rate is significantly greater than the NTRK fusion rate of approximately 1% in CNS tumours. However, it is challenging to compare survival gains specific to IHG following treatment with TRK inhibitors, due to the rarity of this tumour type. However, regardless of tumour grade, the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate for this type of tumour is 42.9% [12]. Considering that the tumour in patient #7 was classified as CNS WHO grade 4, her disease-free survival time of 36 months following treatment with repotrectinib is especially remarkable.

The case of patient #8 (2 y/F), who had a TPM3::NTRK1-fused spinal HGG, highlights the potential efficacy of TRK inhibitor (larotrectinib) therapy in the management of recurrent and challenging tumours [21]. This tumour was diagnosed as GBM in 2017 by the revised WHO2016 classification, and the patient underwent CCRT-TMZ. This type of fusion, previously identified in soft tissue sarcoma and nonbrainstem paediatric HGGs [11, 28, 31], had never been documented in the spinal cord before this case. However, this patient had additional genetic abnormalities, such as MDM4/AKT3 amplification, and experienced multiple recurrences. After the fifth tumour recurrence, the patient was enrolled in a larotrectinib clinical trial, but she died due to tumour progression 22 months after starting larotrectinib.

A French nationwide study reported a median OS time of 13.1 months and a median PFS time of 8.0 months for primary spinal GBM among a generally older population (mean age: 37 years, standard deviation (SD): 16.5). Remarkably, patient #8 achieved an OS time of 22 months post-larotrectinib treatment, significantly exceeding the OS time observed in the French study [1].

The outcomes of these patients demonstrate the notable potential of TRK inhibitors in managing rare and complex cases of tumours such as primary spinal HGG, which accounts for approximately 0.1% of gliomas.

The tumour grade and additional molecular alterations play crucial roles in determining the potential value of NTRK-targeted therapy. Patients with DHGG with additional molecular features alongside NTRK fusion eventually experienced disease progression despite undergoing therapy. Conversely, patients with DLGG without additional genetic alteration who were treated with a TRK inhibitor had stable disease. This pattern indicates that while NTRK-targeted therapies can be effective, their success may vary significantly depending on the tumour grade and the presence of other molecular alterations.

The optimization of NTRK fusion screening using pan-TRK IHC demonstrated high sensitivity, as shown in the 2020 Belgian Ring trial [4] and 2024 CanTRK trial [14], both of which were conducted with the same clones used in our study. However, variability in staining intensity and staining patterns, influenced by different fusion partners, was noted; this variability posed a challenge, especially in CNS tumours, where normal brain tissue also shows pan-TRK IHC positivity [17]. Despite these challenges, our study of twelve tumours harbouring NTRK1 or NTRK2 fusions revealed strong correlations and consistent positive results across various fusion partners. Karakas et al. reported that the sensitivity and specificity of pan-TRK IHC for NTRK fusions were 100% and 88%, respectively [18]. Moreover, the pan-TRK IHC concordance tends to be lower for NTRK3 fusions than for NTRK1 and NTRK2 fusions [11].

Except for a paediatric spinal HGG (GBM-like) and a DIG, which harboured NTRK1 fusions, all other CNS tumours in this study exhibited NTRK2 fusion, consistent with its status as the most common NTRK family member exhibiting fusion in CNS tumours [11]. Importantly, a distinct fusion partner was found in each case, highlighting the molecular heterogeneity within the studied CNS tumours. This observation emphasizes the need for individualized approaches for understanding and targeting specific NTRK fusions in the clinical setting, as well as the necessity of NGS for a final diagnosis.

We report ZBTB43::NTRK2 as a new fusion that has not been previously reported in any tumour. This fusion was identified in the HG IHG of patient #8 (3 y/F) diagnosed according to the WHO2021 diagnostic criteria. The NTRK-fused cerebral gliomas in paediatric patients, with WHO grades ranging across the scale, exhibited no additional genetic alterations. This feature contrasts sharply with the findings in adult GBMs, and this observation highlights the existence of NTRK-fused DLGGs and teaches neuropathologists to be alert in identifying NTRK fusions. Moreover, this need for caution extends beyond HG IHGs to encompass a wide range of gliomas, irrespective of their grade or age at onset.

Torre et al. reported that NTRK-fused gliomas in paediatric patients are of various histologic types, such as DIG, pilocytic astrocytoma, ganglioglioma, and GBM. Our cases included a variety of histopathological classifications, such as IHG, MGNT of the lateral ventricle, astrocytoma with neuropil-like islands, spinal HGG, and GBM. Thus, the histopathology of NTRK-fused CNS tumours is characterized by heterogeneity.

Additionally, our NTRK-fused gliomas were identified across a wide age range of patients and in various locations, including the cerebrum, thalamus, intraventricular area, cerebellum, and spinal cord. Therefore, importantly, NTRK-fused glioma are not exclusively IHG, a paediatric-type DHGG.

Conclusion

The diverse presentations of NTRK-fused CNS tumours complicate the process of diagnosis according to the WHO2021 criteria. However, the therapeutic potential of TRK inhibitors is evident in the positive outcomes obtained. Considering the favourable outcomes of patients undergoing TRK inhibitor therapy, routine screening of all CNS tumours is recommended, particularly in children. Bearing in mind its relatively low specificity, the incorporation of routine pan-TRK IHC testing has the potential to improve both diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of the management of CNS tumours.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Amelot A, Terrier LM, Mathon B, Joubert C, Picart T, Jecko V, Bauchet L, Bernard F, Castel X, Chenin L et al (2023) Natural course and prognosis of primary spinal glioblastoma: a nationwide study. Neurology 100:e1497–e1509. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000206834

Bourhis A, Caumont C, Quintin-Roue I, Magro E, Dissaux G, Remoue A, Le Noac’h P, Douet-Guilbert N, Seizeur R, Tyulyandina A et al (2022) Detection of NTRK fusions in glioblastoma: fluorescent in situ hybridisation is more useful than pan-TRK immunohistochemistry as a screening tool prior to RNA sequencing. Pathology 54:55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathol.2021.05.100

de Carvalho C, Correa D, Tesser-Gamba F, Dias Oliveira I, Saba da Silva N, Capellano AM, de Seixas Alves MT, Dastoli PA, Cavalheiro S, Caminada de Toledo SR (2022) Gliomas in children and adolescents: investigation of molecular alterations with a potential prognostic and therapeutic impact. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 148:107–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03813-1

De Winne K, Sorber L, Lambin S, Siozopoulou V, Beniuga G, Dedeurwaerdere F, D’Haene N, Habran L, Libbrecht L, Van Huysse J et al (2021) Immunohistochemistry as a screening tool for NTRK gene fusions: results of a first Belgian ring trial. Virchows Arch 478:283–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02921-6

Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, Siena S, Shaw AT, Farago AF, Blakely CM, Seto T, Cho BC, Tosi D et al (2020) Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1–2 trials. Lancet Oncol 21:271–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, Krumholz HM, Ross JS (2014) Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005–2012. JAMA 311:368–377. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.282034

Drilon A (2019) TRK inhibitors in TRK fusion-positive cancers. Ann Oncol 30(Suppl 8):viii23–viii30. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz282

Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, DuBois SG, Lassen UN, Demetri GD, Nathenson M, Doebele RC, Farago AF, Pappo AS et al (2018) Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med 378:731–739. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

FDA US (2023) FDA approves repotrectinib for ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-repotrectinib-ros1-positive-non-small-cell-lung-cancer. Accessed January 28, 2024 2024

Gambella A, Senetta R, Collemi G, Vallero SG, Monticelli M, Cofano F, Zeppa P, Garbossa D, Pellerino A, Ruda R et al (2020) NTRK fusions in central nervous system tumors: a rare, but worthy target. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030753

Gatalica Z, Xiu J, Swensen J, Vranic S (2019) Molecular characterization of cancers with NTRK gene fusions. Mod Pathol 32:147–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0118-3

Guerreiro Stucklin AS, Ryall S, Fukuoka K, Zapotocky M, Lassaletta A, Li C, Bridge T, Kim B, Arnoldo A, Kowalski PE et al (2019) Alterations in ALK/ROS1/NTRK/MET drive a group of infantile hemispheric gliomas. Nat Commun 10:4343. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12187-5

Hong L, Shi ZF, Li KK, Wang WW, Yang RR, Kwan JS, Chen H, Li FC, Liu XZ, Chan DT et al (2022) Molecular landscape of pediatric type IDH wildtype, H3 wildtype hemispheric glioblastomas. Lab Invest 102:731–740. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-022-00769-9

Hyrcza MD, Martins-Filho SN, Spatz A, Wang HJ, Purgina BM, Desmeules P, Park PC, Bigras G, Jung S, Cutz JC et al (2024) Canadian multicentric Pan-TRK (CANTRK) immunohistochemistry harmonization study. Mod Pathol 37:100384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100384

Jiang Q, Li M, Li H, Chen L (2022) Entrectinib, a new multi-target inhibitor for cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother 150:112974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112974

Jiang T, Wang G, Liu Y, Feng L, Wang M, Liu J, Chen Y, Ouyang L (2021) Development of small-molecule tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) inhibitors for NTRK fusion cancers. Acta Pharm Sin B 11:355–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.05.004

Kang J, Park JW, Won JK, Bae JM, Koh J, Yim J, Yun H, Kim SK, Choi JY, Kang HJ et al (2020) Clinicopathological findings of pediatric NTRK fusion mesenchymal tumors. Diagn Pathol 15:114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-020-01031-w

Karakas C, Giampoli EJ, Love T, Hicks DG, Velez MJ (2024) Validation and interpretation of Pan-TRK immunohistochemistry: a practical approach and challenges with interpretation. Diagn Pathol 19:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13000-023-01426-5

Kim BS, Seol HJ, Nam DH, Park CK, Kim IH, Kim TM, Kim JH, Cho YH, Yoon SM, Chang JH et al (2017) Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients: a retrospective multicenter observation study in Korea. Cancer Res Treat 49:193–203. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2015.473

Kim H, Lim KY, Park JW, Kang J, Won JK, Lee K, Shim Y, Park CK, Kim SK, Choi SH et al (2022) Sporadic and Lynch syndrome-associated mismatch repair-deficient brain tumors. Lab Invest 102:160–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-021-00694-3

Langston RG, Wardell CP, Palmer A, Scott H, Gokden M, Pait TG, Rodriguez A (2021) Primary glioblastoma of the cauda equina with molecular and histopathological characterization: case report. Neurooncol Adv 3:1154. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdab154

Lanman T, Hayden Gephart M, Bui N, Toland A, Nagpal S (2021) Isolated leptomeningeal progression in a patient with NTRK Fusion+ uterine sarcoma: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 14:1841–1846. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521158

Lee JH, Eom KY, Phi JH, Park CK, Kim SK, Cho BK, Kim TM, Heo DS, Hong KT, Choi JY et al (2021) Long-term outcomes and sequelae analysis of intracranial germinoma: need to reduce the extended-field radiotherapy volume and dose to minimize late sequelae. Cancer Res Treat 53:983–990. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2020.1052

Liu F, Wei Y, Zhang H, Jiang J, Zhang P, Chu Q (2022) NTRK fusion in non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis, therapy, and TRK inhibitor resistance. Front Oncol 12:864666. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.864666

Mohamed F, Kurdi M, Baeesa S, Sabbagh AJ, Hakamy S, Maghrabi Y, Alshedokhi M, Dallol A, Halawa TF, Najjar AA et al (2022) The diagnostic value of Pan-Trk expression to detect neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) gene fusion in CNS tumours: a study using next-generation sequencing platform. Pathol Oncol Res 28:1610233. https://doi.org/10.3389/pore.2022.1610233

Qin H, Patel MR (2022) The challenge and opportunity of NTRK inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23062916

Shyam Sunder S, Sharma UC, Pokharel S (2023) Adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: pathophysiology, mechanisms and clinical management. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8:262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01469-6

Solomon JP, Linkov I, Rosado A, Mullaney K, Rosen EY, Frosina D, Jungbluth AA, Zehir A, Benayed R, Drilon A et al (2020) NTRK fusion detection across multiple assays and 33,997 cases: diagnostic implications and pitfalls. Mod Pathol 33:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0324-7

Theik NWY, Muminovic M, Alvarez-Pinzon AM, Shoreibah A, Hussein AM, Raez LE (2024) NTRK therapy among different types of cancers. Int J Mol Sci Rev Fut Perspect. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042366

Woo HY, Na K, Yoo J, Chang JH, Park YN, Shim HS, Kim SH (2020) Glioblastomas harboring gene fusions detected by next-generation sequencing. Brain Tumor Pathol 37:136–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10014-020-00377-9

Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, Rankin SL, Ju B, Li Y, Zhu X, Qu C, Chen X, Zhang J et al (2014) The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet 46:444–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2938

Xiang S, Lu X (2024) Selective type II TRK inhibitors overcome xDFG mutation mediated acquired resistance to the second-generation inhibitors selitrectinib and repotrectinib. Acta Pharm Sin B 14:517–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.11.010

Yang Y, Li S, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Li Q (2022) Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in malignant tumors: molecular mechanisms and future perspective. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7:329. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01168-8

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HI14C1277), an Institute for Information & Communications Technology Promotion (IITP) grant funded by the Republic of Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2019-0567) and the SNUH Kun-hee Lee Child Cancer & Rare Disease Project, Republic of Korea (grant No.: 24C-039-0000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sung-Hye Park designed and supervised the study. The manuscript was written by Eric Eunshik Kim and edited by Sung-Hye Park. Jae-Kyung Won and Sung-Hye Park reviewed the histopathological slides and genetic studies. Chul-Kee Park, Seung-Ki Kim, Ji Hoon Phi, Sun Ha Paek, Jung Yoon Choi, Hyoung Jin Kang, and Joo Ho Lee contributed to the clinical and radiological descriptions. Hongseok Yun performed the NGS data analysis. All authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No: 1906-02-1037) and was performed according to the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. As this study is a retrospective review of anonymized electronic medical records, pathology, and NGS data utilizing a brain tumour-specific somatic gene panel, informed consent was waived by our IRB under the Korean Bioethics and Safety Act.

Consent for publication

All materials obtained for the medical care of the patients were anonymized and retrospectively reviewed. No extra-human materials were obtained for this study. Under the Korean Bioethics and Safety Act, additional consent for publication was waived.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, E.E., Park, CK., Kim, SK. et al. NTRK-fused central nervous system tumours: clinicopathological and genetic insights and response to TRK inhibitors. acta neuropathol commun 12, 118 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-024-01798-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-024-01798-9