Abstract

Background

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease worldwide. Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors are the first-line treatment for diabetic patients with hypertension. However, whether RAS inhibitors prevent the development of DKD remains controversial. We conducted a retrospective cohort study quantifying the preventive effect of antihypertensive treatment with RAS inhibitors on DKD, using data from specific health check-ups and health insurance claims.

Methods

The study subjects were 418 patients with diabetes and hypertension, drawn from health insurance societies located in Fukuoka and Shizuoka prefectures in Japan. The subjects were divided into three groups, according to the type of antihypertensive treatment they received. They were then compared in terms of the development of DKD, using the diagnostic codes from ICD-10.

Results

Thirty subjects (6.2 %) developed DKD during the study period between April 2011 and September 2013. RAS inhibitor treated group showed a significantly lower risk of DKD [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.35; 95 % confidential interval (CI): 0.16–0.76] compared with the no treatment group.

Conclusion

We conclude that antihypertensive treatment with RAS inhibitors is potentially useful for preventing the development of DKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide [1]. Defined as having a decreased glomerular filtration rate or elevated urine albumin excretion level, CKD is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases as well as end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [2]. The prognosis for diabetic patients is worsened when complicated with CKD. Therefore, special attention has recently been paid to this complication, defined as diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [3, 4]. The progression of DKD is associated with substantial morbidity, mortality, and costs. Therefore, its prevention and management have been increasingly recognized as being important for clinical care, disease management, and public health.

Although the mechanism underlying the development of DKD is still unknown, it is widely accepted that the treatment of hypertension is as important as optimal glycemic control in preventing the development of DKD among diabetic patients [5]. Many studies have demonstrated that renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors such as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) slow the rate of progression of DKD and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease and ESRD [6–9]. However, whether RAS inhibitors prevent the development of DKD remains controversial [10–14].

Currently, the guidelines for the management of hypertension in Japan [15], as well as the United States [16, 17] and Europe [18], recommend RAS inhibitors as first-line treatment for diabetic patients with hypertension. However, the proportion of RAS inhibitors used clinically in diabetic patients remains unclarified. Moreover, the degree to which RAS inhibitors reduce the risk of DKD has not been fully investigated. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective cohort study quantifying the effect of antihypertensive treatment with RAS inhibitors on the prevention of DKD, using specific health check-ups and health insurance claims data.

Methods

Data sources

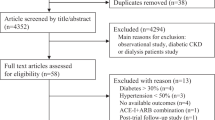

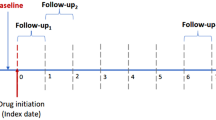

We identified 16,804 beneficiaries aged ≥ 40 years as of March 31, 2011, who worked for health insurance societies located in the Japanese prefectures of Fukuoka and Shizuoka, and attended specific health check-ups in the 2010 fiscal year (FY). From this population, we identified 1022 subjects whose hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level [taken from the national glycohemoglobin standardization program (NGSP)] was ≥ 6.5 %, and/or who were receiving treatment for diabetes. Next, we excluded 522 subjects without hypertension. Subjects with hypertension were identified as those using antihypertensive drugs and/or having a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≥90 mmHg. Blood pressure was determined from the average of two consecutive measurements, separated by 30 s and after 5 min of rest. Owing to the nature of the health checkup, blood pressure was only measured on the day of the checkup. We also excluded 57 subjects diagnosed as having stroke, chronic heart disease, CKD, or anemia, and 25 subjects whose health insurance claim data indicated a diagnosis of kidney disease between January and March 2011. Unfortunately, as this retrospective study was conducted using administrative data, only those with a diagnosed kidney disease were excluded. Finally, we obtained 418 study subjects (Fig. 1). The study was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Kyushu University Institutional Board for Clinical Research (25–340).

Main outcome

The main outcome in this study was the development of DKD. DKD was defined as diabetes with the presence of albuminuria, decreased GFR, or both. We identified patients with DKD between April 2011 and September 2013 on the basis of the diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (Table 1).

Definition of variables

Subjects whose HbA1c values were ≥6.5 %, or who were receiving diabetic treatment in FY 2010 were defined as having DM. Ages were categorized into three groups: 40–49 years, 50–59 years, and ≥60 years. Baseline HbA1c levels were categorized into three groups: ≤7.0, 7.1–8.0, and ≥8.1.

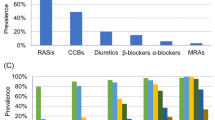

We divided the subjects into three groups, according to the type of antihypertensive treatment and compared the groups in terms of the development of DKD after 2.5 years of follow-up. The ‘no treatment’ group included hypertensive patients who were untreated. The RAS treatment group included those who had received antihypertensive treatment with RAS inhibitors. The RAS inhibitors included ARBs and ACE-Is. Although the direct renin inhibitor is also categorized as a RAS inhibitor, none of the patients received the drug in this study. The non-RAS treatment group included those who had received treatment other than RAS inhibitors such as calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, alpha blockers, and diuretics.

Statistical analyses

Subject characteristics were summarized using frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and median and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. The categorical variables were compared between the three groups using Pearson’s chi-square test, and the continuous variables were compared between the three groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Multiple logistic regression analyses were carried out to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the development of DKD. We set the development of DKD as the dependent variable, and categorized age, gender, HbA1c level, prefecture, and treatment type for hypertension as independent variables.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

We identified 136 patients in the no treatment group, 11 patients in the non-RAS treatment group, and 271 patients in the RAS treatment group. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 2, stratified according to the type of antihypertensive treatment. There were no significant differences in age, age category, gender, prefecture, or median BMI among the three groups. Distributions of HbA1c level, SBP, and DBP were significantly different among the three groups. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the proportions of subjects with hypercholesterolemia and the smoking.

During the follow-up period, 16 (11.8 %), 2 (22.2 %), and 12 (4.4 %) subjects developed DKD in the no treatment, non-RAS treatment, and RAS treatment groups, respectively. Table 3 shows the results of multiple logistic regression analyses. The RAS treatment group had a significantly lower risk of DKD (OR = 0.35; 95 % CI 0.16–0.76, AOR = 0.37; 95 % CI: 0.16–0.83) than the no treatment group. In contrast, the non-RAS treatment group had a higher risk of DKD (OR = 1.67; 95 % CI: 0.33–8.41, AOR = 2.40; 95 % CI: 0.43–13.48) than the no treatment group, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our results indicated that among diabetic patients with hypertension, antihypertensive treatment with RAS inhibitors significantly reduced the risk of developing DKD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using the combination of data from specific health check-ups and health insurance claims to evaluate the preventive effect of RAS treatment on DKD.

Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that RAS inhibitors reduced the likelihood of developing DKD among diabetic patients with hypertension [8, 14]. It is assumed that RAS inhibitors prevent the development of DKD by improving the hemodynamics of the kidney via inhibition of angiotensin II overactivity [19].

RAS inhibitors were used for 96 % of the antihypertensive-treated group, indicating a high rate of compliance with the guidelines. However, 32.5 % of all the subjects with hypertension were not treated for hypertension, despite the fact that diabetic patients with hypertension are at the highest risk of cardiovascular events [20]. The reasons for this are not well understood. One possible reason is that the subjects with hypertension in this study may have included patients not actually hypertensive, but with a one-off abnormal blood pressure reading. A low hypertension treatment rate among diabetic patients has been similarly reported [21, 22]. Turchin et al. suggested that shorter time intervals between physician–patient encounters are associated with improved blood pressure control [23]. In terms of disease management in the future, a survey of consultation rates of the patients, including oral examination, would be necessary.

In June 2013, the Japanese government announced a ‘data health plan’ to be started in FY 2015. This plan will encourage all insurers to engage in disease prevention and health promotion programs based on administrative data such as data from health insurance claims and specific health check-ups. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare will play a central role in promoting the project. Administrative data should be analyzed to monitor patient compliance and adherence to treatment, and to determine whether medical treatment is based on the guidelines. Furthermore, in terms of disease management, health guidance by insurers may play an important role in encouraging consultations.

The non-RAS treatment group showed a higher prevalence of DKD than the no treatment group, although this difference was not statistically significant. The finding could be related to the type of antihypertensive drug that they received; as in both cases, the subjects received antihypertensive drugs with diuretics. It has been suggested that diuretics cause DKD via the deterioration of glycemic control.

This study has several limitations. First, we used administrative data; thus, the confirmation of the development of DKD depended on claims data, rather than clinical data such as urine and blood test results. Second, in this study, the regularity of patient visits and drug compliance were not evaluated; these factors could be related to the development of DKD. Third, the types of RAS inhibitor were not considered. Several studies have demonstrated that each RAS inhibitor has a different mode of action and displays properties that may or may not be replicated by any other RAS inhibitor [13, 24]. In this regard, further studies are necessary to clarify the details of RAS treatment, namely, ARB, ACE-I, or combination therapy. Finally, the homogeneity of the study group may limit the generalizability of our findings to other racial and ethnic groups. Further evidence is needed to corroborate our findings in other populations.

Conclusion

This study suggests that antihypertensive treatment with RAS inhibitors is potentially useful for the prevention of DKD among diabetic patients with hypertension.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- DKD:

-

Diabetic kidney disease

- RAS:

-

Renin-angiotensin system

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- FY:

-

Fiscal year

- NGSP:

-

National glycohemoglobin standardization program

References

de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Weiss NS, Himmelfarb J. Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2532–9.

Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–305.

National Kidney F. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes and CKD: 2012 Update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):850–86.

Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, Hirsch IB, Tuttle KR, Himmelfarb J, et al. Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(2):302–8.

Fioretto P, Bruseghin M, Berto I, Gallina P, Manzato E, Mussap M. Renal protection in diabetes: role of glycemic control. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(4 Suppl 2):S86–9.

Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):861–9.

Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):851–60.

Ruggenenti P, Fassi A, Ilieva AP, Bruno S, Iliev IP, Brusegan V, et al. Preventing microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(19):1941–51.

Parving HH, Lehnert H, Brochner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P, et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):870–8.

Bilous R, Chaturvedi N, Sjolie AK, Fuller J, Klein R, Orchard T, et al. Effect of candesartan on microalbuminuria and albumin excretion rate in diabetes: three randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):11–20. W13-14.

Mauer M, Zinman B, Gardiner R, Suissa S, Sinaiko A, Strand T, et al. Renal and retinal effects of enalapril and losartan in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):40–51.

Mann JF, Schmieder RE, Dyal L, McQueen MJ, Schumacher H, Pogue J, et al. Effect of telmisartan on renal outcomes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):1–10. W11-12.

Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, Craig ME, Craig JC, Strippoli GF. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004136.

Haller H, Ito S, Izzo Jr JL, Januszewicz A, Katayama S, Menne J, et al. Olmesartan for the delay or prevention of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(10):907–17.

Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37(4):253–387.

American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 Suppl 1:S11–66.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–20.

Hypertension EETFftMoA. 2013 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31(10):1925–38.

Reidy K, Kang HM, Hostetter T, Susztak K. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2333–40.

Fioretto P, Bruseghin M, Berto I, Gallina P, Manzato E, Mussap M. Role of cardiovascular risk factors in prevention and treatment of macrovascular disease in diabetes. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 1989;12(8):573–9.

Suh DC, Kim CM, Choi IS, Plauschinat CA, Barone JA. Trends in blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988–2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908–16.

Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA. 2004;291(3):335–42.

Turchin A, Goldberg SI, Shubina M, Einbinder JS, Conlin PR. Encounter frequency and blood pressure in hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2010;56(1):68–74.

Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, Dyal L, Schumacher H, Pogue J, et al. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9638):547–53.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a Grant-In-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (grant no. 25293160).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HM performed literature review and the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. AB helped in the study design, interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript. TN carried out the construction of dataset and helped in statistical analyses. TM helped in manuscript preparation. TI, MI, and HU critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Miyazaki, H., Babazono, A., Nishi, T. et al. Does antihypertensive treatment with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors prevent the development of diabetic kidney disease?. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 16, 22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0024-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0024-y