Abstract

Background

Covid-19 has disrupted the lives of many and resulted in high prevalence rates of mental disorders. Despite a vast amount of research into the social determinants of mental health during Covid-19, little is known about whether the results are consistent with the social gradient in mental health. Here we report a systematic review of studies that investigated how socioeconomic condition (SEC)—a multifaceted construct that measures a person’s socioeconomic standing in society, using indicators such as education and income, predicts emotional health (depression and anxiety) risk during the pandemic. Furthermore, we examined which classes of SEC indicators would best predict symptoms of emotional disorders.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, we conducted search over six databases, including Scopus, PubMed, etc., between November 4, 2021 and November 11, 2021 for studies that investigated how SEC indicators predict emotional health risks during Covid-19, after obtaining approval from PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021288508). Using Covidence as the platform, 362 articles (324 cross-sectional/repeated cross-sectional and 38 longitudinal) were included in this review according to the eligibility criteria. We categorized SEC indicators into ‘actual versus perceived’ and ‘static versus fluid’ classes to explore their differential effects on emotional health.

Results

Out of the 1479 SEC indicators used in these 362 studies, our results showed that 43.68% of the SEC indicators showed ‘expected’ results (i.e., higher SEC predicting better emotional health outcomes); 51.86% reported non-significant results and 4.46% reported the reverse. Economic concerns (67.16% expected results) and financial strains (64.16%) emerged as the best predictors while education (26.85%) and living conditions (30.14%) were the worst.

Conclusions

This review summarizes how different SEC indicators influenced emotional health risks across 98 countries, with a total of 5,677,007 participants, ranging from high to low-income countries. Our findings showed that not all SEC indicators were strongly predictive of emotional health risks. In fact, over half of the SEC indicators studied showed a null effect. We found that perceived and fluid SEC indicators, particularly economic concerns and financial strain could best predict depressive and anxiety symptoms. These findings have implications for policymakers to further understand how different SEC classes affect mental health during a pandemic in order to tackle associated social issues effectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Covid-19, caused by the acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first discovered in December 2019 in the Wuhan city of China. The World Health Organization (WHO) first declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020 [1] and, soon after, a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. In addition to collective fear of the virus exacerbated by its high infectiousness and growing death rate, emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic also led to a worldwide socioeconomic crisis [2, 3]. Many countries were forced to implement movement restrictions and instantaneous lockdown measures to contain the virus and doing so has greatly crippled the global economy [4]. Thus, Covid-19 has emerged as a common stressor to all, as it affected businesses, trades, and production of goods, which has consequently affected the income of a large number of individuals [5].

Covid-19 has been recognized as the worst pandemic of the century, in terms of scale and infection rate [6], and has profoundly impacted people’s mental health [7]. Given this, it is of great relevance to consider whether the social gradient in mental health would continue to be shown in a crisis of such magnitude. Defined as an inverse linear relationship between one’s socioeconomic status and/or conditions and mental health status, the social gradient in mental health theory posits that an individuals’ mental health follows a gradient that is in-line with his or her socioeconomic position in society, and such a relationship exists along a continuum [8]. Indeed, the relationship between SEC and mental health has been well-documented (e.g., [9,10,11]), with studies reporting moderate-to-strong associations between socioeconomic standing and subjective well-being and/or mental health (e.g., [12,13,14,15]). However, few have investigated whether specific SEC indicators are more predictive of mental health conditions over others [16].

Social Economic Conditions (SEC) Indicators

SEC has been defined as an umbrella concept that encompasses both actual (objective) and perceived (subjective) status of a person or a group in a given social context [17]. This should include different facets, such as economic, education, occupation [18], and subjective self-evaluation [19]: (a) economic here refers to traditional material metrics, such as income and assets, which should include both individually- and family-owned (e.g., household income, family assets etc.); (b) education typically refers to years of education attained by an individuals or their parents; (c) occupation is used to reflect the complexity and the intellectual demands of jobs held [17]; and (d) self-evaluated SEC, measured using tools such as the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (MSS) [19], relies on individuals’ self-assessment of their socioeconomic standing in the context of their countries or communities.

However, even if SEC is defined as an overarching concept that includes multiple components, many SEC indicators (e.g., income, education, occupation etc.) do not seem to correlate strongly with one another [20]. Using the example provided in Farah [20], a plumber may not have attained as high an education level as an adjunct professor, but it is the plumber who could be earning a much higher income due to the shortage in this profession. A similar situation can be seen in traditional business owners who may not be highly educated, but could be earning much more than the average population. Thus, it is not surprising that past surveys have found a correlation of only between 0.2 and 0.7 (generally below 0.5) among SEC measures such as income, education, and occupation [21, 22].

In relation, studies have suggested that different SEC indicators are separate, standalone constructs that represent different dimensions of one’s socioeconomic position in society [23]. Relevant to our review, different SEC indicators exhibit differential effects on our emotional health. For instance, higher education (typically viewed as a proxy for good socioeconomic standing) has been linked to higher depressive symptoms, while the opposite was shown for income [24]. Hence, although SEC indicators may overlap, it is valuable for them to be investigated as separate variables to better elucidate their unique effects on emotional health. To-date, it is equivocal as to whether there is a specific SEC measure or cluster of measures that best predicts changes in emotional health, and hence this warrants further investigation, especially with the unique contextual opportunity brought about by Covid-19 as a natural global stressor.

Actual versus perceived SEC indicators

The basic tenet of social inequalities of mental health is the consequences of an uneven distribution of resources across social domains [25]. The fact that the social gradient in health is so robustly observed for a wide range of mental and physical health outcomes [26, 27] and has persisted since the early nineteenth century [28] across both developing and developed nations [29] suggests that the ‘fundamental’ cause of health inequalities is due to SEC disparities [30].

‘Resources’, referred to in the theory of fundamental causes, include tangible material possessions (e.g., wealth, income, assets, social capitals), and intangible ones (e.g., knowledge, power, prestige), which are disproportionately owned by the upper economic classes (e.g., [31,32,33,34]). More importantly, these resources are deemed to be ‘flexible” in that individuals can utilize them in “different ways and in different situations” [30 pS29]. For example, elite individuals have the privilege of choosing world-class treatment for psychiatric conditions, even if that means travelling overseas, and moreover high SEC individuals in positions of power can choose to reduce their workloads (or change jobs for the matter) if they feel that their mental health has been compromised by their work environment. All these privileges and flexibilities endowed by possession of key resources are posited to be the reason for the existence of the social gradient in mental health.

However, studies have shown that in addition to the ‘actual’ possession, the ‘perceived’ lack of such SEC resources could also play a role in the social inequalities in health [35, 36]. Numerous studies using various form of perceived SEC indicators, such as financial threat [37], debt stress [38], and money-management stress [39], perceived financial strain [40], have reported that such perceived financial well-being indicators could affect subjective well-being and mental health. More importantly, recent studies have provided evidence that such financial well-being indicators could potentially mediate the relationship between actual SEC indicators and emotional health [37, 39].

Although actual and perceived SEC indicators are interrelated, as individuals from low SEC backgrounds are more likely to have more concerns about their financial situations [41, 42], there are studies reporting otherwise. For example, individuals from objectively high-SEC backgrounds may still perceive themselves as ‘poor’ [43]. Additionally, there are individuals who do not consider themselves poor despite actually being objectively low in SEC as indicated by traditional income or asset-based measures [44]. In a study by Wang et al. [45] in rural China, 29% of households perceived and reported feeling poor even though they do not meet the objective criteria for poverty. Interestingly, a study by Chang et al. [46] which investigated 1,605 households in Hong Kong, showed that while only 29.06% of the respondents meet the criteria as living below the poverty line, more than 50% of them perceived themselves as poor.

Thus, in this review, we investigated how ‘actual’ and ‘perceived’ SEC categories may be differentially associated with emotional health symptoms in the context of Covid-19.

Static versus fluid SEC indicators

Aside from objectivity of one’s socioeconomic position, it may also be important to compare SEC indicators that are either stagnant or change over time. Past studies have showed that negative changes to one’s socioeconomic position could affect mental health [47, 48]. As a matter fact, the socioeconomic disruptions following disasters, be it man-made or natural, have been shown to be detrimental to mental well-being, as the financial disturbances would result in stress escalation, leading to various mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety [49]. More importantly, such negative consequences are usually more prominent in the low SEC population, as they are likely to lack resources that are needed to cope with the changes following crisis [49].

However, not all SEC indicators are capable to reflect such changes. For instance, education and occupation class are relatively time-invariant and may remain static even in a global health crisis while variables such as income are subject to change. More importantly, research typically compared low and high SEC between individuals, but few have explored how individual’s changes in SEC over time can impact mental well-being [50]. For the few studies which have investigated how changes in SEC influence mental health, the results were mixed.

First, Sareen et al. [47] showed that in addition to having a low income, a decline (i.e., change) in household income was significantly related to a higher risk of mood disorders. This was echoed in a systematic review and meta-analysis by Thomson et al. [48], and in a longitudinal study by Lorant et al. [50], where short-term fluid changes to one’s SEC was associated with greater depression symptoms—although the effects of SEC on mental health was more apparent between subjects instead of within. Conversely, another longitudinal study by Benzeval and Judge [51] in Britain found that a decline in income had only a minor effect on mental health. Similarly, Levesque et al. [52] reported a lack of evidence to support that changes in SEC has any unique effect on mental health separate from the effects of static or current SEC.

In this review, we aimed to investigate how different measurements of one’s SEC, be it static or fluid, are associated with emotional health symptoms (i.e., depression and anxiety), within the context of Covid-19.

Current review

We conducted this systematic review with the aim of answering three pertinent research questions. First, in light of the socioeconomic disruptions brought about by the Covid-19 crisis, we sought to investigate how various classes of SEC indicators were associated with emotional health symptoms (i.e., anxiety and depression). Secondly, we aimed to compare SEC indicators to evaluate whether there were differences in how strongly specific indicators predicted mental health outcomes. Lastly, we assessed whether different groups of SEC indicators (static vs fluid, perceived vs actual) show dissociable effects on emotional health symptoms.

Materials and method

This article constitutes a systematic review, which follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and statement [53]. This work has also been registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021288508).

Article search was conducted over six popular databases (Scopus, ProQuest, PubMed, PsyInfo, OvidMedline, Web of Science), from November 4, 2021 after PROSPERO approved the registration, till November 11, 2021. Five keywords were used: (a) depression or anxiety; (b) Covid-19; (c) socioeconomic; (d) financial; and (e) economic. The combination of the keywords used in the searches was ((depression OR anxiety) AND covid* AND (socioeconomic* OR ses OR financ* OR economic*)). To ensure that only articles conducted on Covid-19 were retrieved, we restricted the publication date to be January 1, 2020 and beyond. The search strategy was developed by the lead author and was used consistently for each database. All subsequent reviews, extraction and consensus were jointly decided by the teams comprising eight reviewers and three assistants. Any disagreements between review authors were resolved through discussion. We used the Covidence, a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews, to assist us in the whole process of the systematic review. The characteristics of the qualitative data based on the PICO model are shown in Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

As we are only 20 months into the pandemic at the time of this review, and in consideration of articles that may still be in the pipeline of publishing, we have decided to include, in addition to published articles, preprints as long as they fulfil our inclusion criteria, which includes: (a) depression and/or anxiety must be studied as the main outcome and measured using validated inventories or scales, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), etc.; (b) socioeconomic status and/or conditions must be studied as a predictor of depression and/or anxiety; articles using SEC as demographic information were excluded; (c) only quantitative studies were included; personal narrative, qualitative, case studies, meta-analyses or review articles were excluded. However, mixed-method studies were included; (d) only articles published on or after January 1, 2020 were included to ensure studies are COVID-19 related; and (e) English version must have been available.

Screening and data extraction

The review process, including screening and data extraction, was carried out on Covidence. For each stage of the screening (title/abstract and full-text reviews), all studies were carefully reviewed by a team comprised of eight members, working independently. Two votes were required for each article to be decided as included or excluded. In case of any conflict, the lead author (JKC) was tasked to resolve it. Data extraction for each article was similarly carried out by any two members of the team independently. A consensus was reached between the two reviewers should there be any conflict.

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality and risk of bias of studies eligible for review were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools for cross-sectional [54] and cohort studies [55]. The tool assesses the trustworthiness, relevance, and results of published papers [54, 55]. The assessment was conducted and verified independently by any two reviewers. Any disagreements between reviewers regarding the qualification and analysis of articles were resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis and coding

In consideration of the diverse ways SEC were measured and used in various studies, we have developed a coding scheme to assist us in data synthesis (Table 2).

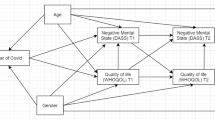

In addition, we further categorized the SEC indicators into ‘static/fluid’ and ‘actual/perceived’ categories depending on how they were measured. ‘Static’ refers to measurements that assessed SEC at a single time-point whereas ‘fluid’ measurements assessed the changes in SEC. ‘Actual’ and ‘perceived’ categorized the measurements in accordance to whether SEC was quantitatively or subjectively assessed. To clarify our point and intention, we used an example listed in Table 3 to illustrate.

Thus, all SEC variables used in articles included in this systematic review were categorized into three levels. Firstly, according to the coding scheme listed in Table 1. Secondly, they were categorized as static or fluid according to the measurement method. Lastly, the SEC variables were further classified as actual or perceived, depending on how they were assessed. The intention for the three levels of categorization was to investigate which method or class of SEC measurements would yield the best result in predicting emotional health risks during the pandemic era.

With the classification, we would then assess how each class of SEC indicators was related to depression and anxiety. For each study, if the SEC class was associated with depression and/or anxiety in accordance with the theory of the social gradient in mental health, as per hypothesized (e.g., higher income/education was associated with lower depression/anxiety), we would count the finding as ‘Expected’. However, if the SEC class was showing the opposite result (e.g., higher income/education was associated with high depression/anxiety), we would count the finding as ‘Contrasting’. In the case that the SEC was not associated with depression and/or anxiety significantly, we would count it as ‘Non-significant’.

Results

Search results

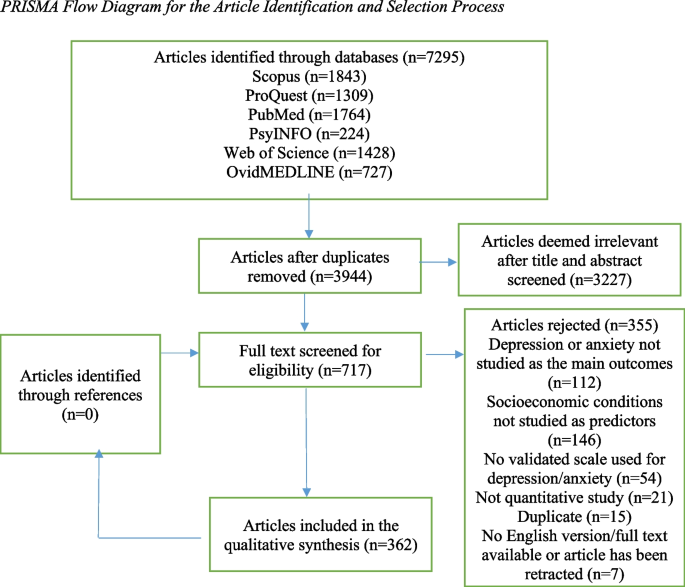

Initially, 7295 studies were imported to Covidence. After removing the duplicate studies (n = 3351), the abstracts of 3944 studies have been screened via Covidence in line with the defined including/exclusion criteria. Next, 717 studies have been found eligible for the full-text review, out of which, 355 studies were excluded. The main reasons for exclusion at the full-text review stage were as follows: (a) socioeconomic conditions have not been examined as primary predictors; (b) depression or anxiety were not studied as the main outcome variables; (c) mental health has not been assessed using a validated scale; (d) not being a quantitative study; (e) duplicate; and (f) the English version was not available, or the study has been retracted. Eventually, 362 studies were included in the data extraction stage. The details of the search and selection process are illustrated in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1).

The articles included in this review involved 324 cross-sectional and repeated cross-sectional studies with 38 longitudinal studies. The total number of participants sampled in these 362 articles was 5,677,007, including 2,342,848 (41.27%) female and 3,334,159 (58.73%) male. The countries where these studies were conducted was summarized in Appendix A [see Supplementary file]. The characteristics and main outcomes of these articles were tabulated as Supplementary Material 2 and Table 4.

Quality appraisal findings

Among 324 cross-sectional/repeated cross-sectional studies included in the review, 242 articles (74.69%) obtained the maximum score of 8 on JBI criteria for the cross-sectional study, 67 articles (20.68%) got a score of 7, and 15 articles (4.63%) scored 6 and below. Of the 38 longitudinal studies, 24 articles (63.16%) received the maximum of 11 points on JBI criteria for the cohort study, 5 (13.16%) got 10 points, 3 (7.89%) obtained a score of 9, 6 studies got a score of 8 and below (15.79%). Details of the quality appraisal were tabulated as Tables 5 and 6.

The relationship between SEC classes and depression/anxiety

As nearly all article used multiple SEC variables in their study, the frequency for each class of SEC used in these studies was first tabulated. In addition, the relationship found between each class of SEC with depression and/or anxiety illustrated in these articles was summarized. The results were showed in Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Our results showed that not all SEC indicators were consistently predicting emotional health outcomes during the Covid-19 pandemic, with some (e.g., economic concerns) performing better than others (e.g., education). From Table 8, we can see that across 362 studies with a total of 1479 SEC indicators used, there were only 646 (43.68%) ‘expected’ (i.e., higher SEC predicting better mental health outcomes) results. Conversely, there were 767 (51.86%) non-significant and 66 (4.46%) ‘contrasting’ (i.e., higher SEC predicting worse mental health outcomes) results. Interestingly, this trend was found in both high income, upper-middle and lower-middle income countries, with 48.63% of studies in high income countries, 56.86% in upper-middle and 55.29% in lower-middle income countries finding non-significant results. This trend was also found in low-income countries, with 55.56% of studies in these countries finding non-significant results (please see Table 10). However, the number of studies conducted in low-income countries was notably limited and therefore, should be interpreted with caution.

SEC Categories and mental health outcomes

In terms of SEC categories (please refer to Table 2), economic concerns as well as financial strain clusters were found to be the most likely predictors of emotional health outcomes. To illustrate, 67.16% of studies reported that economic concerns, such as financial worry [57], financial security stress [58], and concerns about future economic scenario [59] had a significant ‘expected’ relationship with depression/anxiety outcomes. Similarly, 64.13% of studies reported that financial strain, such as economic burden [60], financial problems [61], and ability to meet expenses during lockdown [62] had a significant ‘expected’ relationship with depression/anxiety outcomes.

Conversely, living conditions and education were found to be the least likely to predict emotional health outcomes. 67.12% of studies reported that living conditions such as size of house [63], area of residence (urban or rural) [64], and neighborhood overall environment quality level [65] had no significant relationship with depression/anxiety outcomes. Similarly, 64.11% of studies reported that educational attainment including number of years of education received [66] and having been to college or not [67] had no significant relationship with depression/anxiety outcomes.

Static and fluid SEC indicators and emotional health outcomes

From Table 9, we can see that ‘fluid’ SEC indicators (i.e., measurements that assessed changes in SEC over a period of time) were more likely to predict depression/ anxiety outcomes compared to ‘static’ SEC indicators (i.e., measurements that assessed SEC at a single time-point). To illustrate, 58.59% of studies reported that ‘fluid’ SEC indicators such as loss of employment [68] and reduced family income [69] had a significant ‘expected’ relationship with depression/anxiety outcomes, whereas only 39.59% of studies reported the same for ‘static’ SEC indicators such as current employment status [70] and monthly income [71].

Actual and perceived SEC indicators and emotional health outcomes

From Table 9, ‘Perceived’ (i.e., subjectively assessed) SEC indicators were found to be more likely to predict depression/anxiety compared to ‘actual’ (i.e., objectively assessed) SEC indicators. 60.64% of studies reported that ‘perceived’ SEC indicators such as self-reported food insecurity [72] and SEC assessed by the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status [73] had a significant ‘expected’ relationship with depression/anxiety outcomes, whereas only 36.04% of studies reported the same for ‘actual’ SEC indicators such as food security measured by Household Food Security Survey Module [74] and SEC assessed by an asset-based index [75].

Discussion

Our comprehensive systematic review has identified a wide-array of studies using heterogeneous indicators to predict symptoms of anxiety and depression throughout Covid-19. Despite the variability in measures, our results revealed general patterns that seem to challenge the widely accepted social gradient in mental health and theory of fundamental causes.

Differences in predictive power of sec indicators

First, we have uncovered that not all SEC indicators were strongly predictive of emotional health symptoms during Covid-19, as majority of studies conducted across the globe reported non-significant relationships between the two variables regardless of country income classification. This contradicts pre-Covid-19 findings reporting moderate-to-strong associations between socioeconomic standing and subjective well-being and/or mental health [12,13,14,15]. Overall, around 40% of studies aligned with the social gradient in mental health theory, but more than 50% revealed no significant results. However, using economic concerns as a measure of SEC showed that the social gradient theory is still applicable for most studies.

These findings suggest that the relationship between SEC and mental health may vary in accordance to how SEC was assessed and measured. Our findings are corroborated by one pre-pandemic study [76], which report that self-reported physical health is more intertwined with SEC compared to mental health. This could be due to mental health being more influenced by internal factors such as psychological state or personality, compared to external factors such as SEC.

In the context of Covid-19, lockdown measures may have equalised the risk for mental health conditions as those from higher social classes would have been unable to utilise economic resources to mitigate health concerns and loss of freedom. This is a notion consistent with the theory of fundamental causes described in the introduction section of this review. Indeed, pandemic related stressors may have impacted individuals regardless of socioeconomic class. Uncertainty caused by the pandemic may have been more detrimental to mental health compared to one’s SEC [77], and difficulty coping with uncertainty is a common trait across various mood and anxiety disorders [78, 79].

Reduced access to and availability of mental health services may have also played a role in people of all social classes developing symptoms of anxiety and depression. At the height of the pandemic, countries and health organisations were forced to redirect funding, space, equipment, and facilities towards treating patients experiencing Covid-19 complications. Indeed, a survey by the WHO [80] found that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted or halted critical mental health services in 93% of countries worldwide. Moreover, due to social distancing measures, 67% saw disruptions to counselling and psychotherapy appointments, 65% to critical harm reduction services, and 45% to opioid agonist maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Thus, those with a history of mental health conditions likely experienced worsened symptoms, while those who developed symptoms during the pandemic were unable to access urgent care and treatment, leading to a global mental health crisis transcending SEC.

Economic concerns and financial strain

In our systematic review, the SEC category, ‘economic concerns’, emerged as being most predictive of emotional health during Covid-19, based on percentage of papers reporting significant relationships. Relevant papers revealed that the construct assessed under this category centred around ‘concerns, worries or stress arising from current or future uncertainty about one’s economic position’, although the items can be phased quite differently, e.g., ‘fear of job loss’, ‘financial insecurity’ etc. This construct may be closely linked with worrying, a transdiagnostic construct that has been shown to be robustly predictive of depression and anxiety [81, 82], though in this aspect, such worrying is economically-induced.

Defined as the tendency to dwell on uncertainty of future problems or events in an obsessive, repetitive and negative manner [83], worrying, particularly pathological worrying, is associated with the onset and intensity of mood and anxiety disorders [84,85,86]. Constant worrying functions like rumination, which takes up variable cognitive resources, resulting in depleted cognitive functioning abilities that are necessary for daily life [87,88,89]. Such cognitive deficits are expected to result in reduced problem-solving abilities, leading to adverse life circumstances, which would consequently affect one’s mental health. As illustrated by allostatic load theory, when cumulative effects of life stressors exceed a person’s buffer to cope or adapt, an allostatic overload occurs which results in poorer physical and mental health [90].

In conjunction, several studies in our review reported significant links between emotional health and the financial strain cluster, which encompasses one’s ability to pay bills/rent/mortgage, having sufficient funds to retire, as well as one’s perceived financial state, and financial wellbeing. This is consistent with pre-Covid 19 studies reporting that perceived inability to pay bills or afford food is associated with greater anxiety, depression, stress, feelings of isolation, and alcohol dependence [91,92,93].

Financial strain may serve as a superior predictor of mental health as it intersects both objective and subjective SEC measures. This means it reflects changes in one’s objective circumstances (e.g., ability to pay bills), while also encompassing subjective measures (e.g., satisfaction with finances) that exerts influence over mental health [94].

Empirically, decreased objective financial resources was found to be associated with increased financial strain, and in turn, financial strain emerged as a strong and robust predictor of poor mental health in older adults [94]. Financial strain and economic concerns being perceived measures also likely strengthens their ability to predict mental health since our review has found that perceived indicators are more correlated with anxiety and depression than objective ones. This will be discussed further in the section entitled ‘Perceived and Objective SEC Indicators’.

Fluid and static SEC indicators

Research done prior to Covid-19 has reported that fluid indicators of SEC (e.g., job loss or income loss) are highly predictive of poor mental health outcomes [95,96,97]. The inverse has also been observed, wherein income gains (via, for instance, increasing minimum wage) lead to stark improvement in mental health symptoms [98]. However, to our knowledge, our review is the first to clarify that fluid SEC indicators may be more informative of changes in emotional health compared to static indicators (e.g., current income or occupation) during Covid-19.

A sudden negative change in income or employment would profoundly impact one’s lifestyle; affected individuals would be forced to alter spending habits, cut back on leisure to focus on saving for essential goods, or even resort to drastic measures such as removing their children from school. This period of adjustment can culminate in severe stress. In addition, the shame and stigma associated with job loss or unemployment can also lead to depressive feelings [99]. By contrast, people who have had consistently low income or have been unemployed pre-pandemic may be more resilient to declines in mental health linked to Covid-19 as they are more accustomed to lifestyles associated with poverty.

Perceived and objective SEC indicators

Next, consistent with prior literature we report that perceived SEC indicators (e.g., measures used for financial strain) correlate more with emotional health outcomes compared to objective indicators. This phenomenon has been observed across continents including in Asia and Europe [76, 100, 101]. Additionally, a current meta-analysis across 357 studies found that subjective SEC corresponded to subjective well-being better than income or educational attainment [15]. Research also reports that objective SEC only affects mental health via promoting changes in subjective SEC [100] suggesting that subjective or perceived SEC serves as an important mediating variable.

One potential reason for perceived SEC being a superior predictor of mental health outcomes is that it perhaps serves as a more precise measure of social position. This is because perceived SEC considers not only current social standing, but past contexts and future prospects [102]. As an example, two individuals with post-graduate qualifications may be considered similar in social standing based on objective measures of SEC. However, if one of them graduated from a less prestigious university, they may rate their subjective SEC as being lower due to future financial and career prospects not being as lucrative.

Another reason is that subjective SEC appears to have more of an influence over physiological stress pathways, as perceiving oneself as financially disadvantaged impacts the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis leading to enhanced production of cortisol [103,104,105]. Dysregulated HPA is also observed in clinical depression [106]. Thus, poor SEC may be elevating mental health symptoms via dysregulating the HPA axis [101].

Living conditions and education

Lastly, we have observed that living conditions and education level appear weakly predictive of anxiety and depression symptoms. Work published prior to Covid-19 congruently report mixed findings pertaining to these indicators. On one hand, education, particularly parental education, and crowding (an indicator of living condition) is reported to predict children and adolescent mental health outcomes [107, 108]. In contrast, other systematic reviews and meta-analysis report that education and neighbourhood living conditions do not strongly predict mental-health and well-being [76, 109]. The lack of predictive power may be attributed to these being objective SEC measures which, as highlighted above, do not influence emotional health as strongly as perceived indicators.

The weak link we have observed between education and emotional health may be considered surprising at first as high educational attainment typically leads to lower rates of unemployment and occupations that provide economic resources beneficial to quality of life [110]. Nevertheless, the association between emotional health and education is unlikely to be linear. Research has instead revealed that at higher levels of educational attainment, additional increases in formal education is decreasingly beneficial for mental health [111]. For instance, advancing from an undergraduate to a post-graduate qualification is less significant for mental health compared to going from primary to secondary level of education [111]. Moreover, being overeducated is reported to lead to diminishing mental health, as it is associated with decreased job satisfaction, increased job stress, and greater prevalence of depressive symptoms [24, 111,112,113]. This may, in part, be due to a skills mismatch and overeducated people feeling under-challenged in their careers [114].

Additionally, it is perhaps difficult to detect a strong effect of living conditions on emotional health due to the studies in our review using extremely varied measures that may not be capturing the same construct or even indeed socioeconomic constructs, including rural versus urban housing, crowding, noise levels, presence of balcony or garden, number of rooms, area of house, etc. Hence, it is difficult to isolate a specific variable that could be most predictive of emotional health within this SEC indicator.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our systematic review revealed that there are differential effects of various classes of SEC indicators in predicting emotional health. Notably, the economic concerns and financial strain clusters emerged as stronger predictors of depression and anxiety. Surprisingly, classic SEC measures, such as education and income, did not exhibit strong predictability during this period. In addition, ‘fluid’ and ‘perceived’ class of SEC indicators have been shown to display better predictive power on depression and anxiety as compared to ‘static’ and ‘actual’. These findings suggest that the strength of the association between SEC and mental health is dependent upon the class of SEC indicator used.

Limitations

While our systematic review has compellingly unveiled how diverse SEC indicators differentially affect emotional health during Covid-19, it is not without limitations. First, because of the heterogeneity in measures, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis to elucidate whether observed trends in studies show statistical significance. Next, our review only included studies with data collected during the pandemic, and hence we could not compare pre-Covid and post-Covid findings in more detail to truly determine whether Covid-19 has resulted in differences in how SEC indicators are predictive of emotional health symptoms. In addition, since our review has only included articles on depression and/or anxiety as the overall gauge of the emotional health status of the general population, we could have missed out articles that studied on other specific mental health disorders during the pandemic, and we could not rule out the linkages between SEC with these specific mental disorders might be different compared to general emotional health as revealed in our review. Thus, though our review has interrogated an important link between SEC and anxiety/depressive symptoms, we acknowledge that it would be imperative in future work to probe other mental health disorders that were also affected by the pandemic. Also, our review only includes articles that were published in journals or in pre-print servers as of November 11, 2021. Articles published after this date were not included in this review.

Articles included in this review

1) Silva [115] | 2) Bhandari [116] | 3) Guerin [117] |

4) Alharbi [118] | 5) Elezi [119] | 6) Campos [120] |

7) Dawel [66] | 8) Agberotimi [121] | 9) Chakraborty [62] |

10) Al Zabadi [71] | 11) Balakrishnan [122] | 12) d'Arqom [123] |

13) Bower [70] | 14) Chen [65] | 15) Alkhamshi [124] |

16) Généreux [125] | 17) Hall [126] | 18) Islam [127] |

19) Brouillette [128] | 20) Frankel [58] | 21) He [129] |

22) Badellino [130] | 23) da Silva Júnior [131] | 24) Sharif Nia [132] |

25) Hoque [133] | 26) Aruta [134] | 27) Dharra [135] |

28) Cui [136] | 29) Graupensperger [137] | 30) Chasson [138] |

31) Gong [139] | 32) Cost [140] | 33) Luo [141] |

34) Ettman [142] | 35) Hajek [143] | 36) Han [144] |

37) Heanoy [68] | 38) Brunoni [145] | 39) Ali [146] |

40) De Pietri [73] | 41) Ren [147] | 42) Hueniken [57] |

43) Karing [148] | 44) Gouvernet [149] | 45) Betini [150] |

46) Barcellos [67] | 47) Elhadi [151] | 48) Ames-Guerrero [152] |

49) Ali [61] | 50) Hu [153] | 51) Harjana [154] |

52) Gong [155] | 53) Bérard [156] | 54) De France [157] |

55) Frontera [158] | 56) Alpay [159] | 57) Hammarberg [160] |

58) Conti [161] | 59) Irfan [69] | 60) Jewell [162] |

61) Dhar [163] | 62) Ahmmed [164] | 63) Figueroa-Quiñones [165] |

64) Islam [166] | 65) Pensgaard [167] | 66) Al Mutair [168] |

67) Cevher [169] | 68) Chen [60] | 69) Zhang [170] |

70) Ahmed [171] | 71) Karaivazoglou [172] | 72) Basheti [173] |

73) Flores [174] | 74) Abrams [175] | 75) Chen [176] |

76) Hart [177] | 77) Bahar Moni [178] | 78) Cao [179] |

79) Huang [180] | 80) Guo [181] | 81) Effati-Daryani [182] |

82) Every-Palmer [183] | 83) Cortés-Álvarez [184] | 84) Fitzpatrick [185] |

85) Gur [186] | 86) Fu [187] | 87) Akkaya-Kalayci [188] |

88) Díaz-Jiménez [59] | 89) Ben-Kimhy [189] | 90) Goularte [190] |

91) Fu [191] | 92) Ganson [192] | 93) Gloster [193] |

94) Donnelly [194] | 95) Delmastro [195] | 96) Fountoulakis [196] |

97) Simha [197] | 98) Antiporta [198] | 99) Hou [199] |

100) Fornili [200] | 101) Das [201] | 102) Fukase [202] |

103) Fanaj [203] | 104) Blix [204] | 105) Feter [205] |

106) Harling [206] | 107) Batterham [207] | 108) Hao [208] |

109) Haliwa [209] | 110) Cerecero-Garcia [210] | 111) Creese [211] |

112) Alkhaldi [212] | 113) Hoyt [213] | 114) Beach [214] |

115) Oh [215] | 116) BC [216] | 117) Davis [217] |

118) Beutel [218] | 119) Kim [219] | 120) Dehkordi [220] |

121) Hu [221] | 122) Mekhemar [222] | 123) Hoffart [223] |

124) Adnine [224] | 125) Bryson [225] | 126) Geren [226] |

127) Angwenyi [75] | 128) Guerrero [227] | 129) Fröhlich [228] |

130) Coley [229] | 131) Law [230] | 132) Sun [231] |

133) Heo [232] | 134) Hertz-Palmor [233] | 135) Lindau [234] |

136) Ruengorn [235] | 137) Repon [236] | 138) Owens [237] |

139) Varma [238] | 140) Stampini [239] | 141) Esteban-Gonzalo [240] |

142) Mistry [241] | 143) Schmits [242] | 144) Feurer [243] |

145) Mana [244] | 146) Marmet [245] | 147) Wright [246] |

148) Kobayashi [247] | 149) Oginni [248] | 150) Maffly-Kipp [249] |

151) Shuster [250] | 152) Ogrodniczuk [251] | 153) Moya [252] |

154) Kjeldsted [253] | 155) Ochnik [254] | 156) Robertson [255] |

157) Senturk [256] | 158) Sams [257] | 159) Sirin [258] |

160) Lueck [259] | 161) Ribeiro [260] | 162) Tasnim [261] |

163) Zhang [262] | 164) Rudenstine [263] | 165) Zheng [264] |

166) Shalhub [265] | 167) Vujčić [266] | 168) Liang [267] |

169) Nagasu [268] | 170) Vicens [269] | 171) Posel[270] |

172) Romeo [271] | 173) Thombs [272] | 174) Wong [273] |

175) Meng [274] | 176) Porter [275] | 177) Knolle [276] |

178) Jones [277] | 179) Wickens [278] | 180) Racine [279] |

181) Mikocka-Walus [280] | 182) Thayer [281] | 183) Landa-Blanco [282] |

184) van Rüth [283] | 185) Koyucu [284] | 186) Ettman [285] |

187) Kämpfen [286] | 188) Jacques-Aviñó [287] | 189) Li [288] |

190) Xiao [289] | 191) Ueda [290] | 192) Garre-Olmo [291] |

193) Polsky [292] | 194) Silverman [293] | 195) Lin [294] |

196) Sinawi [295] | 197) Kar [296] | 198) Serafini [297] |

199) Yörük [298] | 200) Reagu [299] | 201) Khademian [300] |

202) Reading Turchioe [301] | 203) Saito [302] | 204) Torrente [303] |

205) Wong [304] | 206) Yang [305] | 207) Wang [306] |

208) Khoury [307] | 209) Trujillo-Hernández [308] | 210) Luo [309] |

211) Wang [310] | 212) Lee [311] | 213) Lei [312] |

214) Ping [313] | 215) Solomou [314] | 216) Song [315] |

217) García-Fernández [316] | 218) Gasparro [317] | 219) Newby [318] |

220) McCracken [319] | 221) Islam [320] | 222) Zhao [321] |

223) Winkler [322] | 224) Shatla [323] | 225) Massad [324] |

226) Iob [325] | 227) Nelson [326] | 228) Généreux [327] |

229) Kuang [328] | 230) Smith [329] | 231) Khan [330] |

232) Van Hees [331] | 233) Ballivian [332] | 234) Wilson [333] |

235) Montano [334] | 236) Skapinakis [335] | 237) Yáñez [336] |

238) Shevlin [337] | 239) Wanberg [24] | 240) Sayeed [338] |

241) Wang [339] | 242) Wang [340] | 243) Marthoenis [341] |

244) Toledo-Fernández [342] | 245) Tuan [343] | 246) Sisay [344] |

247) Mekhemar [345] | 248) Klimkiewicz [346] | 249) Mâsse [347] |

250) Watkins-Martin [348] | 251) Nam [349] | 252) Malesza [350] |

253) Prati [63] | 254) López-Castro [351] | 255) Ettman [352] |

256) Kwong [353] | 257) Minhas [354] | 258) Meraya[355] |

259) Rutland-Lawes [64] | 260) Garvey [356] | 261) Yao [357] |

262) Lai [358] | 263) Sultana [359] | 264) Wang [360] |

265) Liu [361] | 266) Kohls [362] | 267) Millevert [363] |

268) Zheng [364] | 269) Passavanti [365] | 270) Peng [366] |

271) Yan [367] | 272) Liu [368] | 273) Zhao [369] |

274) Vrublevska [370] | 275) Shen [371] | 276) Kinser [372] |

277) Rondung [373] | 278) Yadav [374] | 279) Song [375] |

280) Sazakli [376] | 281) Jolliff [377] | 282) Hyun [378] |

283) Krumer-Nevo [379] | 284) Pagorek-Eshel [380] | 285) Mistry [381] |

286) Kaplan Serin [382] | 287) Leaune [383] | 288) McDowell [384] |

289) Killgore [385] | 290) Qiu [386] | 291) Zhou [387] |

292) Kira [388] | 293) Su [389] | 294) Wolfson [390] |

295) Mekhemar [391] | 296) King [392] | 297) Teng [393] |

298) Saw [394] | 299) Oryan [395] | 300) Kim [396] |

301) Qiu [397] | 302) Zhao [398] | 303) Miklitz [399] |

304) Sundermeir [400] | 305) Gangwar [401] | 306) Mojtahedi [402] |

307) Obrenovic [403] | 308) McArthur [404] | 309) Oliva [405] |

310) Wagner [406] | 311) Shahriarirad [407] | 312) Okubo [408] |

313) Jia [409] | 314) Kikuchi [410] | 315) Robinson [411] |

316) Olibamoyo Olushola [412] | 317) Suleiman [413] | 318) Mani [414] |

319) López Steinmetz [415] | 320) Widyana [416] | 321) Thomas [417] |

322) Li [418] | 323) Salameh [419] | 324) Zajacova [72] |

325) Yamamoto [420] | 326) Zwickl [421] | 327) Gama [422] |

328) Solomou [423] | 329) Malek Rivan [424] | 330) Nishimura [425] |

331) Sabat [426] | 332) Torkian [427] | 333) Suarez-Balcazar [74] |

334) Westrupp [428] | 335) Li [429] | 336) Scarlett [430] |

337) Pinchoff [431] | 338) Tsai [432] | 339) Msherghi [433] |

340) Myhr [434] | 341) Kusuma [435] | 342) Rassu [436] |

343) Sabate [437] | 344) Lee [438] | 345) Jing [439] |

346) Shangguan [440] | 347) Liu [441] | 348) Van de Velde [442] |

349) Saadeh [443] | 350) Ravens-Sieberer [444] | 351) Mikolajczyk [445] |

352) Santangelo [446] | 353) Morin [447] | 354) Spiro [448] |

355) Kira [449] | 356) Leach [450] | 357) Juchnowicz [451] |

358) Song [452] | 359) Emery [453] | 360) Zarrouq [454] |

361) Restar [455] | 362) Smallwood [456] |

Abbreviations

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

- EW:

-

Economic-worries

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SEC:

-

Socioeconomic conditions

- STAI:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), 12 October 2020. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIg9260rDL6QIVFreWCh3PIw0_EAAYASABEgKCofD_BwE. Assessed on 27 Sep 2022.

McKibbin W, Fernando R. The economic impact of COVID-19. Australian National University. Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Asian Economic Papers. 2020:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1162/asep_a_00796

Serafini G, Parmigiani B, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Sher L, Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 2020;113:531. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201.

Kaim A, Gering T, Moshaiov A, Adini B. Deciphering the COVID-19 health economic dilemma (HED): a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9555.

Akbulaev N, Mammadov I, Aliyev V. Economic impact of COVID-19. Sylwan. 2020;164(5). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3649813

Wilder-Smith A. COVID-19 in comparison with other emerging viral diseases: risk of geographic spread via travel. Trop Dis, Travel Med Vac. 2021;7(1):1–1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40794-020-00129-9.

Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LM, Gill H, Phan L, Chen-Li D, Iacobucci M, Ho R, Majeed A, McIntyre RS. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001.

Shepherd CC, Li J, Zubrick SR. Social gradients in the health of Indigenous Australians. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):107–17. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300354.

Deaton A. Measuring and understanding behavior, welfare, and poverty. Am Econ Rev. 2016;106(6):1221–43. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.106.6.1221.

Gilman SE, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice GM, Buka SL. Family disruption in childhood and risk of adult depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):939–46. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.939.

Leech SL, Larkby CA, Day R, Day NL. Predictors and correlates of high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among children at age 10. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(2):223–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000184930.18552.4d.

Bøe T, Øverland S, Lundervold AJ, Hysing M. Socioeconomic status and children’s mental health: results from the Bergen child study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(10):1557–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0462-9.

Finegan M, Firth N, Wojnarowski C, Delgadillo J. Associations between socioeconomic status and psychological therapy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(6):560–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22765.

Lorant V, Deliège D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):98112–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf182.

Tan JJ, Kraus MW, Carpenter NC, Adler NE. The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2020;146(11):970. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000258.

McLaughlin KA, Costello EJ, Leblanc W, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1742–50.

Perera-Wa H, Salehuddin K, Khairudin R, Schaefer A. The relationship between socioeconomic status and scalp event-related potentials: a systematic review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;15:601489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.601489.

Duncan GJ, Magnuson K. Socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning: moving from correlation to causation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2012;3(3):377–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1176.

Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy, white women. Health Psychol. 2000;19(6):586. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586.

Farah MJ. The neuroscience of socioeconomic status: correlates, causes, and consequences. Neuron. 2017;96(1):56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.034.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, Posner S. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294(22):2879–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.22.2879.

Chen E, Paterson LQ. Neighborhood, family, and subjective socioeconomic status: How do they relate to adolescent health? Health Psychol. 2006;25(6):704. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.704.

Geyer S, Hemström Ö, Peter R, Vågerö D. Education, income, and occupational class cannot be used interchangeably in social epidemiology. Empirical evidence against a common practice. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60(9):804–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.041319.

Wanberg CR, Csillag B, Douglass RP, Zhou L, Pollard MS. Socioeconomic status and well-being during COVID-19: a resource-based examination. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(12):1382. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000831.

Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;1:80–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626958.

Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.49.1.15.

Keating DP, Hertzman C, editors. Developmental health and the wealth of nations: Social, biological, and educational dynamics. New York: Guilford press; 2000.

Antonovsky A. Social class, life expectancy and overall mortality. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1967;45(2):31–73.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. The lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6.

Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1_suppl):S28-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383498.

Hackman DA, Betancourt LM, Gallop R, Romer D, Brodsky NL, Hurt H, Farah MJ. Mapping the trajectory of socioeconomic disparity in working memory: parental and neighborhood factors. Child Dev. 2014;85(4):1433–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12242.

Jefferson AL, Gibbons LE, Rentz DM, Carvalho JO, Manly J, Bennett DA, Jones RN. A life course model of cognitive activities, socioeconomic status, education, reading ability, and cognition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1403–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03499.x.

Kuruvilla A, Jacob KS. Poverty, social stress & mental health. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126(4):273.

Noble KG, Houston SM, Brito NH, Bartsch H, Kan E, Kuperman JM, Akshoomoff N, Amaral DG, Bloss CS, Libiger O, Schork NJ. Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(5):773–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3983.

Euteneuer F. Subjective social status and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(5):337–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000083.

Zahodne LB, Kraal AZ, Zaheed A, Sol K. Subjective social status predicts late-life memory trajectories through both mental and physical health pathways. Gerontology. 2018;64:466–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487304.

Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, Fiksenbaum L, Bell CM. Psychometric evaluation of the Financial Threat Scale (FTS) in the context of the great recession. J Econ Psychol. 2013;36:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2013.02.005.

Drentea P. Age, debt and anxiety. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;1:437–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676296.

Netemeyer RG, Warmath D, Fernandes D, Lynch JG Jr. How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. J Consumer Res. 2018;45(1):68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109.

Selenko E, Batinic B. Beyond debt. A moderator analysis of the relationship between perceived financial strain and mental health. Social Sci Med. 2011;73(12):1725–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.0223.

Jones AD. Food insecurity and mental health status: a global analysis of 149 countries. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):264–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.008.

Ryu S, Fan L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among US adults. J Fam Econ Issues. 2023;44(1):16–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-022-09820-9.

Zanin L. On Italian households’ economic inadequacy using quali-quantitative measures. Soc Indic Res. 2016;128(1):59–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1019-1.

Rojas M. Well-being and the complexity of poverty: A subjective well-being approach. WIDER research paper; 2004.

Wang H, Zhao Q, Bai Y, Zhang L, Yu X. Poverty and subjective poverty in rural China. Soc Indic Res. 2020;150:219–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02303-0.

Chang Q, Peng C, Guo Y, Cai Z, Yip PS. Mechanisms connecting objective and subjective poverty to mental health: Serial mediation roles of negative life events and social support. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113308.

Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJ. Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):419–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15.

Thomson RM, Igelström E, Purba AK, Shimonovich M, Thomson H, McCartney G, Reeves A, Leyland A, Pearce A, Katikireddi SV. How do income changes impact on mental health and wellbeing for working-age adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(6):e515–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00058-5.

Mao W, Agyapong VI. The role of social determinants in mental health and resilience after disasters: Implications for public health policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2021;9:658528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.658528.

Lorant V, Croux C, Weich S, Deliège D, Mackenbach J, Ansseau M. Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(4):293–8. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020040.

Benzeval M, Judge K. Income and health: the time dimension. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(9):1371–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00244-6.

Levesque AR, MacDonald S, Berg SA, Reka R. Assessing the impact of changes in household socioeconomic status on the health of children and adolescents: a systematic review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2021;6:91–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00151-8.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Lisy K, Qureshi R, Mattis P. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. 2020a. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Analytical_Cross_Sectional_Studies2017_0.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2021.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromatari sE SK, Sfetcu R. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Cohort_Studies2017_0.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2021.

Fantom N, Serajuddin U. The World Bank's classification of countries by income. The World Bank; 2016.

Hueniken K, Somé NH, Abdelhack M, Taylor G, Marshall TE, Wickens CM, Hamilton HA, Wells S, Felsky D. Machine learning-based predictive modeling of anxiety and depressive symptoms during 8 months of the COVID-19 global pandemic: repeated cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Mental Health. 2021;8(11):e32876. https://doi.org/10.2196/32876.

Frankel LA, Kuno CB, Sampige R. The relationship between COVID-related parenting stress, nonresponsive feeding behaviors, and parent mental health. Curr Psychol. 2021;8:1–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02333-y.

Díaz-Jiménez RM, Caravaca-Sánchez F, Martín-Cano MC, De la Fuente-Robles YM. Anxiety levels among social work students during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Soc Work Health Care. 2020;59(9–10):681–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2020.1859044.

Chen X, Wu R, Xu J, Wang J, Gao M, Chen Y, Pan Y, Ji H, Duan Y, Sun M, Du L. Prevalence and associated factors of psychological distress in tuberculosis patients in Northeast China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06284-4.

Ali M, Uddin Z, Ahsan NF, Haque MZ, Bairagee M, Khan SA, Hossain A. Prevalence of mental health symptoms and its effect on insomnia among healthcare workers who attended hospitals during COVID-19 pandemic: a survey in Dhaka city. Heliyon. 2021;7(5):e06985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06985.

Chakraborty T, Subbiah GK, Damade Y. Psychological distress during COVID-19 lockdown among dental students and practitioners in India: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(S 01):S70-8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1719211.

Prati G. Mental health and its psychosocial predictors during national quarantine in Italy against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34(2):145–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1861253.

Rutland-Lawes J, Wallinheimo AS, Evans SL. Risk factors for depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in middle-aged and older adults. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(5):161. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.997.

Chen Y, Jones C, Dunse N. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and psychological distress in China: does neighbourhood matter? Sci Total Environ. 2021;759:144203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144203.

Dawel A, Shou Y, Smithson M, Cherbuin N, Banfield M, Calear AL, Farrer LM, Gray D, Gulliver A, Housen T, McCallum SM. The effect of COVID-19 on mental health and wellbeing in a representative sample of Australian adults. Front Psych. 2020;11:579985. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579985.

Barcellos S, Jacobson M, Stone AA. Varied and unexpected changes in the well-being of seniors in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Plos One. 2021;16(6):e0252962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252962.

Heanoy EZ, Shi L, Brown NR. Assessing the transitional impact and mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic onset. Front Psychol. 2021;11:607976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607976.

Irfan M, Shahudin F, Hooper VJ, Akram W, Abdul Ghani RB. The psychological impact of coronavirus on university students and its socio-economic determinants in Malaysia. INQUIRY. 2021;58:00469580211056217. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580211056217.

Bower M, Buckle C, Rugel E, Donohoe-Bales A, McGrath L, Gournay K, Barrett E, Phibbs P, Teesson M. ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health. Int J Hous Pol. 2021;14:1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1940686.

Al Zabadi H, Alhroub T, Yaseen N, Haj-Yahya M. Assessment of depression severity during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic among the Palestinian population: a growing concern and an immediate consideration. Front Psych. 2020;11:570065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570065.

Zajacova A, Jehn A, Stackhouse M, Choi KH, Denice P, Haan M, Ramos H. Mental health and economic concerns from March to May during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Insights from an analysis of repeated cross-sectional surveys. SSM-Popul Health. 2020;12:100704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100704.

De Pietri S, Chiorri C. Early impact of COVID-19 quarantine on the perceived change of anxiety symptoms in a non-clinical, non-infected Italian sample: effect of COVID-19 quarantine on anxiety. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;4:100078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100078.

Suarez-Balcazar Y, Mirza M, Errisuriz VL, Zeng W, Brown JP, Vanegas S, Heydarian N, Parra-Medina D, Morales P, Torres H, Magaña S. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and well-being of Latinx caregivers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7971. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157971.

Angwenyi V, Kabue M, Chongwo E, Mabrouk A, Too EK, Odhiambo R, Nasambu C, Marangu J, Ssewanyana D, Njoroge E, Ombech E. Mental health during COVID-19 pandemic among caregivers of young children in Kenya’s urban informal settlements. A cross-sectional telephone survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10092. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910092.

Read S, Grundy E, Foverskov E. Socio-economic position and subjective health and well-being among older people in Europe: a systematic narrative review. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(5):529–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023766.

Rettie H, Daniels J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Psychol. 2021;76(3):427. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000710.

Jensen D, Cohen JN, Mennin DS, Fresco DM, Heimberg RG. Clarifying the unique associations among intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016;45(6):431–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1197308.

McEvoy PM, Mahoney AE. To be sure, to be sure: Intolerance of uncertainty mediates symptoms of various anxiety and depressive disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2011;2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.007

World Health Organization. The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological and substance use services: results of a rapid assessment, 5 October 2020. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/impact-covid-19-mental-neurological-and-substance-use-services-results-rapid-assessment?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAn-2tBhDVARIsAGmStVkuuSW-vO_hc37gS2Zzq2_M-Th70KUjakNfD7mdcz6nxQSYIjlAH6waAmGOEALw_wcB. Assessed on 27 Sep 2022.

Segal Z, Williams M, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford publications; 2018.

Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(2):163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163.

Borkovec TD, Robinson E, Pruzinsky T, DePree JA. Preliminary exploration of worry: some characteristics and processes. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21(1):9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(83)90121-3.

Hong RY. Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(2):277–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.006.

McLaughlin KA, Borkovec TD, Sibrava NJ. The effects of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behav Ther. 2007;38(1):23–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003.

Szabó M. The emotional experience associated with worrying: anxiety, depression, or stress? Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011;24(1):91–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615801003653430.

Lyubomirsky S, Tucker KL, Caldwell ND, Berg K. Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(5):1041. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1041.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x.

Davis RN, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cogn Ther Res. 2000;24(6):699–711. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005591412406.

McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(18):2093–101. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004.

Klesges LM, Pahor M, Shorr RI, Wan JY, Williamson JD, Guralnik JM. Financial difficulty in acquiring food among elderly disabled women: results from the women’s health and aging study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):68. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.1.68.

Stack RJ, Meredith A. The impact of financial hardship on single parents: an exploration of the journey from social distress to seeking help. J Fam Econ Issues. 2018;39(2):233–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9551-6.

Richardson T, Elliott P, Roberts R, Jansen M. A longitudinal study of financial difficulties and mental health in a national sample of British undergraduate students. Commun Ment Health J. 2017;53(3):344–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0052-0.

Wilkinson LR. Financial strain and mental health among older adults during the great recession. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016;71(4):745–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw001.

Bubonya M, Cobb-Clark DA, Wooden M. Job loss and the mental health of spouses and adolescent children. IZA J Labor Econ. 2017;6(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-017-0056-1.

Olesen SC, Butterworth P, Leach LS, Kelaher M, Pirkis J. Mental health affects future employment as job loss affects mental health: findings from a longitudinal population study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-144.

Dooley D, Fielding J, Levi L. Health and unemployment. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17(1):449–65.

Reeves A, McKee M, Mackenbach J, Whitehead M, Stuckler D. Introduction of a national minimum wage reduced depressive symptoms in low-wage workers: a quasi-natural experiment in the UK. Health Econ. 2017;26(5):639–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3336.

Stankunas M, Kalediene R, Starkuviene S, Kapustinskiene V. Duration of unemployment and depression: a cross-sectional survey in Lithuania. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-174.

Hoebel J, Maske UE, Zeeb H, Lampert T. Social inequalities and depressive symptoms in adults: the role of objective and subjective socioeconomic status. Plos One. 2017;12(1):e0169764. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169764.

Sasaki Y, Shobugawa Y, Nozaki I, Takagi D, Nagamine Y, Funato M, Chihara Y, Shirakura Y, Lwin KT, Zin PE, Bo TZ. Association between depressive symptoms and objective/subjective socioeconomic status among older adults of two regions in Myanmar. Plos One. 2021;16(1):e0245489. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245489.

Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):855–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0.

Derry HM, Fagundes CP, Andridge R, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Lower subjective social status exaggerates interleukin-6 responses to a laboratory stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(11):2676–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.026.

Seeman M, Merkin SS, Karlamangla A, Koretz B, Seeman T. Social status and biological dysregulation: The “status syndrome” and allostatic load. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:143–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.002.

Wright CE, Steptoe A. Subjective socioeconomic position, gender and cortisol responses to waking in an elderly population. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(6):582–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.01.007.

Lopez-Duran NL, Kovacs M, George CJ. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation in depressed children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(9):1272–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.016.

Evans GW, Lercher P, Kofler WW. Crowding and children’s mental health: the role of house type. J Environ Psychol. 2002;22(3):221–31. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2002.0256.

Reiss F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2013;90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026.

Richardson R, Westley T, Gariépy G, Austin N, Nandi A. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(11):1641–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1092-4.

Kettunen J. Education and unemployment duration. Econ Educ Rev. 1997;16(2):163–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7757(96)00057-x.

Bracke P, Pattyn E, von dem Knesebeck O. Overeducation and depressive symptoms: diminishing mental health returns to education. Sociol Health Illn. 2013;35(8):1242–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12039.

Gal G, Kaplan G, Gross R, Levav I. Status inconsistency and common mental disorders in the Israel-based world mental health survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(12):999–1003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0393-2.

Solomon BC, Nikolaev BN, Shepherd DA. Does educational attainment promote job satisfaction? The bittersweet trade-offs between job resources, demands, and stress. J Appl Psychol. 2022;107(7):1227. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000904.

Link BG, Lennon MC, Dohrenwend BP. Socioeconomic status and depression: the role of occupations involving direction, control, and planning. Am J Sociol. 1993;98(6):1351–87. https://doi.org/10.1086/230192.

Silva AN, Guedes CR, Santos-Pinto CD, Miranda ES, Ferreira LM, Vettore MV. Demographics, socioeconomic status, social distancing, psychosocial factors and psychological well-being among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147215.

Bhandari S, Sharma L. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental well-being of employees: a study of mental wellness of employees during COVID-19 in India. Cardiometry. 2021 (19). https://doi.org/10.18137/cardiometry.2021.19.7889

Guerin RJ, Barile JP, Thompson WW, McKnight-Eily L, Okun AH. Investigating the impact of job loss and decreased work hours on physical and mental health outcomes among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(9):e571–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002288.

Alharbi R, Alnagar D, Abdulrahman AT, Alamri O. Statistical methods to represent the anxiety and depression experienced in Almadinh KSA during Covid-19. JP J Biostat. 2021;18(2):231–48. https://doi.org/10.17654/JB018020231.

Elezi F, Tafani G, Sotiri E, Agaj H, Kola K. Assessment of anxiety and depression symptoms in the Albanian general population during the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic. Ind J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):S470. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_842_20.

Campos JA, Martins BG, Campos LA, Marôco J, Saadiq RA, Ruano R. Early psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: a national survey. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2976. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092976.

Agberotimi SF, Akinsola OS, Oguntayo R, Olaseni AO. Interactions between socioeconomic status and mental health outcomes in the nigerian context amid covid-19 pandemic: a comparative study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:559819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559819.

Balakrishnan V, Mohamad Nor A, Zainal NZ. COVID-19 nationwide lockdown and it’s emotional stressors among Malaysian women. Asia Pac J Soc Work Dev. 2021;31(3):236–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2021.1886976.

d’Arqom A, Sawitri B, Nasution Z, Lazuardi R. “Anti-COVID-19” medications, supplements, and mental health status in Indonesian mothers with school-age children. Int J Women’s Health. 2021;13:699. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S316417.

Alkhamshi SS, Abdulrahman bin Shalhoubm H, Hammad MA, Alshahrani HF. Covid-19 pandemic: psychological, social and economic impacts on Saudi society. Acad J Interdiscip Stud. 2021;10(3):335-. https://doi.org/10.36941/AJIS-2021-0088.

Généreux M, Roy M, David MD, Carignan MÈ, Blouin-Genest G, Qadar SZ, Champagne-Poirier O. Psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: main stressors and assets. Glob Health Promot. 2022;29(1):23–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/17579759211023671.

Hall LR, Sanchez K, da Graca B, Bennett MM, Powers M, Warren AM. Income differences and COVID-19: impact on daily life and mental health. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25(3):384–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2021.0214.

Islam MS, Rahman ME, Banik R, Emran MG, Saiara N, Hossain S, Hasan MT, Sikder MT, Smith L, Potenza MN. Financial and mental health concerns of impoverished urban-dwelling Bangladeshi people during COVID-19. Front Psychol. 2021;12:663687. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663687.

Brouillette MJ, Koski L, Scott S, Austin-Keiller A, Fellows LK, Mayo NE. Factors influencing psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in people aging with HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2022;38(5):421–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/AID.2021.0024.

He M, Cabrera N, Renteria J, Chen Y, Alonso A, McDorman SA, Kerlow MA, Reich SM. Family functioning in the time of COVID-19 among economically vulnerable families: risks and protective factors. Front Psychol. 2021;12:730447. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.730447.

Badellino H, Gobbo ME, Torres E, Aschieri ME, Biotti M, Alvarez V, Gigante C, Cachiarelli M. ‘It’s the economy, stupid’: Lessons of a longitudinal study of depression in Argentina. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(2):384–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764021999687.

da Silva Júnior AE, de Lima Macena M, de Oliveira AD, Praxedes DR, de Oliveira Maranhão Pureza IR, Bueno NB. Racial differences in generalized anxiety disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic among Brazilian University Students: a national survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(5):1680–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01107-3.

Sharif Nia H, Akhlaghi E, Torkian S, Khosravi V, Etesami R, Froelicher ES, Pahlevan SS. Predictors of persistence of anxiety, hyperarousal stress, and resilience during the COVID-19 epidemic: a national study in Iran. Front Psychol. 2021;12:671124. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671124.

Hoque MN, Hannan A, Imran S, Alam MA, Matubber B, Saha SM. Anxiety and its determinants among undergraduate students during E-learning in Bangladesh amid covid-19. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;6:100241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100241.

Aruta JJ, Callueng C, Antazo BG, Ballada CJ. The mediating role of psychological distress on the link between socio-ecological factors and quality of life of Filipino adults during COVID-19 crisis. J Commun Psychol. 2022;50(2):712–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01322-x.