Abstract

Background

In the case of preterm birth, the idealized postnatal period is replaced by an anxious and even traumatic experience for parents. Higher prevalence of parental anxiety, postnatal depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder has been observed in mothers of preterm infants up to 18 months after childbirth. There is increasing evidence that proprioceptive stimulation has a beneficial effect on preterms’ short-term outcomes. Could this care also have an impact on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms? We reviewed recent publications on the impact on parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms of delivering tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation to their premature newborn.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review by searching the PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar databases for English-language publications from the past 10 years. We focused on the mothers or fathers of infants born preterm (before 37 weeks of gestation) who provided tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation to their premature newborn in the neonatal intensive care unit. Relevant outcomes were the parents’ anxiety, stress, depressive symptoms, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, assessed with reliable standardized inventories.

Results

Eleven articles were included in the systematic review. Results suggested a beneficial effect of parents’ early tactile and kinesthetic stimulation of their preterm infants.

Conclusions

These interventions may act as protective factors against the occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in parents and deserve to be studied further in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Preterm birth disrupts early infant development. The technical and stressful environment of the incubator, which separates premature babies from their parents, replaces the natural intrauterine environment. Sleepwake cycles are often interrupted by medical care [1]. The developing brains of premature babies are exposed to stimuli that may be detrimental to their maturation [2], with either too much or too little sensory input [3]. This is referred to as dystimulation. Medical comorbidities and sedation impair physiology and makes them less available to interact. On the parental side, the idealized postnatal period is replaced by an anxious and even traumatic experience [4,5,6]. Parents often express guilt and anxiety about their child’s survival and feel unable to fulfill their parental role [7, 8].

The interaction between the immaturity of the neonate’s organism and this technical environment may affect long-term outcomes, which are consensually reported in the scientific literature for both children and their parents [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. There is evidence that the severity of the infant’s clinical status is related both to the degree of prematurity and to birth weight [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Multifactorial and diffuse brain damage leads to the loss of vulnerable cells [9,10,11], but even preterm infants with no overt brain lesions have impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes. These neurodevelopmental problems include impairment of gross and fine motor skills, behavior, and cognition (language, executive functions, and social cognition) [12, 15,16,17,18]. In addition, more than 35% of children born prematurely go on to exhibit insecure attachment behaviors in relationships with others [19]. In the long term, these intricate difficulties lead to academic, socio-emotional, relational, and behavioral problems [12, 15,16,17,18]. On the parental side, a higher prevalence of parental anxiety, postnatal depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been observed in the mothers of preterm infants [20] up to 18 months after childbirth [21]. The parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms appear to interact with the child’s developmental difficulties (especially in terms of attachment and emotional and cognitive development) in a vicious circle [22, 23].

To avoid these negative consequences of preterm birth, developmental care has been introduced into many neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Among the most widely studied and practiced forms are the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP), the “skin-to-skin care” (SSC) and the “Kangaro mother care” (KMC; which key features are early, continuous skin-to-skin contact between the mother and her baby along with exclusive breastfeeding, ideally [24]). They aim to avoid overstimulation, by protecting the newborn’s most vulnerable sensory systems (e.g., covering the incubator with a blanket, reducing noise levels in the NICU, etc.). They also aim to reduce interruptions of the sleepwake cycle by organizing medical care during the child’s quiet periods of wakefulness and preserving sleep times. Finally, they aim to promote affective contact with parents through the practice of SSC [25]. SSC consists in placing the newborn on the parent’s bare chest. NIDCAP and the SSC have been shown to have many positive effects on the child, such as weight gain, somatic development, maturation of brain electrical activity as measured by EEG, fewer medical complications, a shorter hospital stay, and long-term cognitive development [26], as well as on maternal wellbeing [27, 28].

Several teams are currently testing whether targeted enhancement of preterm infants’ sensory environment has an additional positive effect, compared with the usual developmental care. The common purpose is to provide stimulation to promote physiological maturation of neuronal networks sensitive to (or dependent on) sensory input. One challenge is to avoid dystimulation by compensating for under-stimulation in the tactile, kinesthetic or vestibular sensory modalities while protecting the visual and auditory modalities from over-stimulation. Some authors have investigated the potential of massage care, which consists of touch with gentle pressure. Several studies have shown that massage care in very preterm infants is associated with reduced stress levels, less late sepsis, improved hemodynamic stability, increased weight gain, and enhanced parental wellbeing [29,30,31,32]. Other studies have focused on the effects of tactile and kinesthetic stimulation (TKS) on preterm infants. TKS is a combination of moderate tactile stimulation and kinesthetic stimulation through flexion and extension movements of the limbs. It has been shown to have many beneficial effects on physiological measures (e.g., heart rate, state of alertness, breastfeeding) [33, 34], length of hospital stay [33], maturation of brain electrical activity measured by EEG [35], early interactions and attachment [36], and neurodevelopmental outcomes [36,37,38].

These studies underline the relevance of these types of stimulation for premature children. But what about the parents who provide this stimulation? As we mentioned earlier, preterm mothers have been found to have higher prevalence of parental anxiety, postnatal depression, and PTSD [20] up to 18 months after childbirth [21]. The main purpose of this systematic review was to highlight the impact on parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms of providing stimulation (i.e., SSC and TKS) to their premature newborn.

There is a consensus that children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes are the result of interaction between their genetic and neurobiological phenotype and their environment [39,40,41], which includes their relationship with their parents. Parents’ behaviors toward their children therefore affect their development [42, 43]. Parents’ ability to interact with their children has been shown to be modified by anxiety and depressive symptoms [44, 45]. When interacting with their young children, parents with these disorders oscillate between moments of withdrawal and moments of intrusion [44, 45]. These atypical early interactions affect children’s cognitive, social and emotional development [46,47,48,49,50]. In very young children, sleep and feeding difficulties have been reported [51]. In extreme cases, if parents’ mental health difficulties are left untreated, they can become a risk factor for child neglect and even abuse [52], especially when the child has specific needs (e.g., prematurity or disability) [53]. It is therefore relevant to ask whether the care given to premature infants could also be beneficial for their parents, if they are the ones who provide it. The present systematic review investigated this question by focusing on the impact on parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms of providing tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation to their premature newborn.

Methods

Objective

We used the PopulationInterventionComparisonOutcomes (PICO) method to specify the components of our systematic review’s main research question. The population (P) was the parents of premature newborns, the intervention (I) was tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation delivered by parents to their premature newborn, in comparison (C) with standard care in the NICU (including developmental care), and the outcomes (O) were parental anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Procedure

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar databases, using the following keywords: (preterm AND (kangaroo care OR skin-to-skin OR massage OR tactile OR proprioceptive OR kinesthetic) AND (anxiety OR depression OR depressive OR traumatic OR stress)). Additional terms were associated with these keywords (e.g., for preterm: premature, prematurity). We restricted the search to English-language articles published within the previous 10 years (i.e., between January 2012 and December 2022). We also searched the reference lists of included studies for additional eligible articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We looked for studies that focused on the mothers or fathers of infants born prematurely (before 37 weeks of amenorrhea) who provided tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation to their premature newborn in NICU. Relevant outcomes were the parents’ anxiety, stress, depressive symptoms, or symptoms of PTSD, as assessed with reliable standardized inventories. Articles in which parents performed additional stimulation in another sensory modality (e.g., auditory stimulation through music) were excluded. Studies assessing symptoms without the use of reliable standardized inventories were also excluded.

Study selection and quality assessment

We used the PRISMA method to select the articles. An initial selection was made by the first author according to the title, and a second selection was based on the abstract. A final selection was made after a full-text reading of each article and analysis of its quality using the Joanna Briggs Inventory checklists. These checklists assess the quality of articles according to the following criteria: randomization, blinding of participants and assessors, treatment groups, follow-up of participants, methods of measuring outcomes (tools, time, etc.), and statistical analyses. Each criterion was rated as either met (yes), not met (no), not clearly met (unclear), or not applicable. It should be noted that the participant blinding criterion could not be applied here, given that the stimulation was provided by the participants themselves. The percentage risk of bias was therefore calculated on the remaining items (i.e., 10 items out of 13 for the Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials, and 10 items out of 11 for the Checklist for Cohort Studies). A high risk of bias corresponds to a score between 0% and 50%, a moderate risk to a score between 51% and 70%, and a low risk to a score between 71% and 100%. A percentage risk of bias was calculated for each article (see Appendix 1).

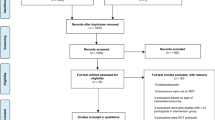

The first author helped by a master student performed the selection and qualitative assessment of the articles. In case of discrepancy about selected/rejected articles, the whole team assessed the articles under consideration and built consensus whether or not each article should be retained. The article selection steps are detailed in Fig. 1.

Data extraction

The data extracted from the articles regarding the population, stimulation (nature, duration, frequency, etc.), measurement tools, measured outcomes, and statistical results were compiled independently by the first author and the master student. Their respective extractions were then compared by the team to fill in any missing data. Given the heterogeneity of the methodologies and results in the selected articles, we undertook a qualitative synthesis of the data.

Results

Of the 309 studies we screened, 63 were assessed for eligibility. A total of 34 articles were excluded after reading the abstract. A further 18 articles were excluded after reading the full text for the following reasons: (a) 16 articles dealt with an ineligible intervention (i.e., nontactile and/or nonkinesthetic stimulation); (b) one article did not measure parental anxiety and depressive symptoms with reliable standardized inventories; and (c) one article was not in English. Accordingly, 11 studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review [27, 28, 31, 32, 36, 38, 54,55,56,57,58].

Two articles reported the effect of KMC [56, 57], four focused on the effect of SSC [27, 28, 54, 57], three on the effect of TKS [36, 38, 58], and two compared the effects of SSC and TKS [32, 33].

The studies we selected involved infants born between 25 and 37 weeks of gestation. All these studies included late preterm infants (33–37 weeks), eight studies included very preterm infants (26–32 weeks) and six studies included extremely preterm infants (< 26 weeks). These data are summarized in Table 1. After examining the respective effects of SSC, KMC and TKS on parents’ anxiety, stress, depressive symptoms, and symptoms of PTSD, we report the comparative effects of SSC versus TKS.

Parental symptoms were assessed with a number of standardized tools. Anxiety was assessed with the StateTrait Anxiety Inventory [59] in five articles [28, 31, 36, 54, 58], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [60] in one article [55], and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [61] in one article [32]. Parental stress was assessed with the Parenting Stress Index in two articles [38, 54], the Swedish Parenthood Stress Questionnaire in one article [57], and the DASS-21 in one article [31]. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [62] in three articles [27, 56, 57], the Beck Depression Inventory [63] in one article [54], the HADS in one article [55], and the DASS-21 in one article [32]. PTSD was not assessed in any of the articles.

Effects of skin-to-skin care on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms

Two trials consistently showed an association between SSC and a reduction in maternal anxiety was consistently demonstrated in two studies. In these studies, SSC was performed one hour per day for periods ranging from 1 to 14 days. Sweeney et al. [28] demonstrated a significant reduction in maternal anxiety after practicing SSC [27]. Feldman et al. [54] reported lower maternal anxiety at 3 and 6 months postpartum among mothers of babies born between 25 and 34 weeks who had practiced SSC in NICU, but this difference was no longer significant of age 10 years [54].

Only two studies assessed the effect of SSC on parental stress, and their results were divergent. Feldman et al. [54] reported lower parental stress at 3 and 6 months postpartum among mothers who had practiced SSC in NICU, but this difference was no longer significant at 10 years [54]. Mörelius et al. [57] found no significant effect of SSC on parental stress among either mothers or fathers [57].

Two studies found a beneficial effect of SSC on parents’ depressive symptoms. One study reported lower depressive scores in the first month postpartum in mothers who practiced SSC [27]. Mörelius et al. [57] showed lower scores of depressive symptoms in mothers who practiced continuous skin-to-skin (i.e., 24 h per day, 7 days per week) than in mothers who practiced standard SSC (i.e., as many times as the parent wished), but this effect did not reach statistical significance [57].

Effects of kangaroo mother care on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms

Two studies reported the effect of KMC (skin-to-skin contact combined with exclusive breastfeeding) on parental and/or depressive symptoms. However, it is important to note that in these trials, skin-to-skin contact was not practiced continuously, contrary to the recommended methodology in the KMC. Indeed, in these studies, SSC was performed between one and four hours per day for one week. Erduran et al. [56] thus refers to this as “intermittent kangaroo care”.

Only the Rao et al.’s study [55] reported the effect of KMC on parental anxiety. It showed a decrease in parental anxiety symptoms during the first week postpartum after performing KMC [55].

Both studies found a beneficial effect of KMC. Rao et al. [55] showed a significant decrease in depressive symptoms during the first week postpartum after performing KMC [55] and Erduran et al. [56] observed fewer depressive symptoms during the first month postpartum in parents who practiced KMC, although this effect did not reach statistical significance [56].

Effects of tactile and kinesthetic stimulation on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms

The effect of TKS on maternal anxiety was investigated in two studies. In these studies, TKS was performed for at least 8 min per day (maximum of 45 min per day), for 2–60 days). Both studies found that mothers who practiced TKS had less anxiety than those who did not, from the first week after childbirth [36, 58].

A single study investigated the effect of TKS on maternal stress [38]. This study reported no significant difference in stress at 3 months postpartum between mothers of infants born after 28–34 weeks of gestation who practiced TKS and those who did not.

None of the studies investigated the effect of TKS on parents’ depressive symptoms.

Effects of skin-to-skin contact versus tactile and kinesthetic stimulation on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms

Two articles compared the effects of SSC versus TKS on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms, yielding divergent results [31, 32]. The first study compared the anxiety levels of mothers of infants born after 28–36 weeks of gestation who received either SSC, TKS, or standard care (control group) [31]. Mothers in the SSC and TKS groups had significantly lower anxiety scores than those in the control group, but there was no significant difference between mothers in the SSC versus TKS groups. The second study compared the effects of SSC and TKS on the anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms of mothers of infants with a gestational age of 28–36 weeks [32]. In this study, mothers who performed SSC had significantly lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms than mothers who performed TKS.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to highlight recent findings on the effects on parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms of providing tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation to their premature newborn. To address this issue, we screened the results of 11 articles dealing with tactile sensory interventions, including four articles on the effects of SSC, two on the effects of KMC, three on the effects of TKS, and two articles comparing the effects of SSC and TKS.

Results were unequivocal for the beneficial effects of sensory stimulation on maternal anxiety, with a significant decrease in symptoms from the first week of practice, whether the stimulation was solely tactile (SSC) or tactile and kinesthetic (TKS). Results were more mixed for parental stress, as most studies failed to find significant effects of either SSC or TKS. Regarding depressive symptoms, studies of SSC only found a trend toward a significant effect. It should be recalled that none of the studies specifically investigated the effect of TKS on depressive symptoms, and the comparison between TKS and SSC in one study failed to yield conclusive results. Moreover, none of the studies investigated the effects of either SSC or TKS on the symptoms of PTSD. There is therefore a dearth of scientific research on the effects of SSC and/or TKS on depressive symptoms and the symptoms of PTSD. Given that depressive symptoms in the postnatal period have been identified as being predictive of PTSD symptoms [64], it would be even more relevant to assess all the components of parental anxiety and depressive symptoms in relation to sensory interventions. Similarly, only two studies compared the effects of SSC and TKS. The heterogeneity of their methods and their divergent results did not allow us to draw any conclusions regarding the differential effects of TKS versus SSC. Moreover, as SSC has become standard care in NICUs, it would be more ecological for future studies to investigate the additional effect of TKS when associated with SSC [65].

The authors provided different explanations for the beneficial effects of SSC and TKS on parental anxiety and depressive symptoms. One of these focused on the physiological benefits of tactile and kinesthetic contact. Maternal oxytocin production has been found to be disturbed after premature birth [54, 66], and more generally in parents with anxiety and depressive symptoms [67,68,69,70]. However, tactile and affectionate contacts increase plasma levels of oxytocin and endorphins in both infants and their parents [71,72,73]. These hormones have been shown to improve parents’ mood by reducing their cortisol levels (associated with stress) [74,75,76,77] and giving them feelings of security, wellbeing, and happiness [77, 78]. The second explanation took more account of the social environment and the psychological mechanisms involved. As the parentinfant interaction is disrupted, the parents of premature infants often express a feeling of parental incompetence [79,80,81] characterized by the feeling of not being useful in caring for their baby (as most newborn care is performed by professionals and not by the parents themselves), and not being able to understand or respond to their baby’s needs. This contributes to the emergence of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and feelings of powerlessness that heighten the traumatic nature of hospitalization in NICU [4, 82, 83]. Practicing SSC or TKS places parents at the center of their infant’s care, giving them an important role. The daily benefits that they can see in their child’s condition reduce their feeling of parental incompetence [84]. By acting at both physiological and psychological levels, TKS is likely to have a dual effect. SSC and TKS may therefore act as protective factors against the occurrence of parental anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Further studies are needed to confirm the beneficial effects of SSC and/or TKS on parents’ depressive symptoms and symptoms of PTSD. As indicated earlier, studies have not always yielded significant statistical results. These divergent results can be explained by the heterogeneity of the interventions, in terms of the frequency and duration of stimulation. The different methods used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, in terms of tools and timing, may be another explanation. Finally, the discrepancy in results could also be explained by the diversity of the samples. The studies included in this review were conducted among the parents of preterm babies of different gestational ages. The parents and their babies therefore faced different risk factors, newborn health conditions, and hospitalization durations, which may have had differential effects on their anxiety and depressive symptoms. Maternal anxiety and depressive symptoms have been shown to correlate with the infant’s gestational age [21, 85,86,87], medical risk factors such as birth weight [86,87,88], neonatal risk [48, 51, 86, 87, 89], cesarean Sect. [21] and medical complications [85, 88, 89], and length of hospital stay [90]. Sensory interventions may therefore need to be longer to have a statistically significant beneficial effect in parents, if the neonatal risk is particularly high. In addition, most studies only included mothers in the intervention protocol, whether it be for the practice of sensory stimulation or the assessment of anxiety and depressive symptoms. However, fathers also form part of the child’s daily relational environment, and recent studies have shown that anxiety and depressive symptoms are also present in the fathers of preterm infants [91, 92], and therefore have an impact on these infants’ development [93,94,95,96,97]. Accordingly, it is important to include fathers in future studies and to develop scales to assess perinatal anxiety and depressive symptoms in fathers.

There can no longer be any doubt about the importance of developing interventions to reduce parental anxiety and depressive symptoms, given that there is so much at stake. Maternal anxiety and depressive symptoms are one of the main causes of postpartum suicide [98], and a risk factor for child neglect or abuse [99]. Moreover, parental anxiety and depressive symptoms have been shown to adversely affect sleep quality and feeding in early life [51], and cognitive, affective, social, and behavioral development in later childhood, even outside the context of prematurity [44, 48, 100,101,102,103,104]. Studies supporting the diathesisstress theory, according to which early exposure to stressors makes individuals more sensitive and receptive to negative influences from their subsequent environment, have shown that parental anxiety and depressive symptomatology has an even more detrimental effect on child development when it occurs in a context that is already a source of vulnerability, as in the case of preterm birth [48, 105, 106]. Researchers and clinicians need to work together to develop such interventions to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms in the parents of preterm infants.

Limitations

Our systematic review had three main limitations. First, the heterogeneity of the infants’ gestational age in the included studies prevented us from specifying the effects of tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation according to the stage of prematurity. This is nevertheless a promising avenue for research, given that researchers have demonstrated a correlation between parental symptoms and gestational age [21, 107, 108], and the benefits of stimulation increase with the severity of prematurity [109,110,111].

Second, some of the studies did not provide enough details about the characteristics of their sample (e.g., gestational age), the timing of the assessment of parental anxiety and depressive symptoms, and the sensory stimulation protocol. The validation of inventories translated into different languages and cultures might make it easier to reproduce these studies. Similarly, detailed descriptions of the stimulation provided to infants born preterm are mandatory for further replication studies.

Third, we selected studies published in English within the previous 10 years to examine the results of the most recent international scientific literature. However, there are certainly older studies and/or studies published in other languages that would provide interesting results.

Conclusion

In conclusion, providing early tactile and kinesthetic stimulation to their preterm infants seems to have a beneficial effect on parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms. These interventions protect against the occurrence of symptoms and could be used for prevention in at-risk populations.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PTSD:

-

posttraumatic stress disorder

- NICU:

-

neonatal intensive care unit

- NIDCAP:

-

Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program

- SSC:

-

skin-to-skin care

- TKS:

-

tactile and kinesthetic stimulation

- PICO:

-

Population–Intervention–Comparison–Outcomes

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- DASS-21:

-

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale

References

Als H. Individualized, family-focused developmental care for the very low birthweight preterm infant in the NICU. Psychol Dev Low Birthweight Child. 1992;6:341–88.

Philbin MK, Ballweg DD, Gray L. The effect of an intensive care unit sound environment on the development of habituation in healthy avian neonates. Dev Psychobiol. 1994;27(1):11–21.

Borghini A, Forcada-Guex M, Nix CM. XIII. Prématurité et interventions précoces [Internet]. Recherches en périnatalité. Presses Universitaires de France; 2014 [cité 11 mai 2021]. Disponible sur: https://www.cairn.info/recherches-en-perinatalite--9782130628545-page-247.htm.

Lahouel-Zaier W. Impact de l’hospitalisation périnatale sur l’établissement du lien d’attachement entre le bébé et sa mère. Devenir 31 mars 2017;Vol 29(1):27–44.

Rosenblum LA, Andrews MW. Influences of environmental demand on maternal behavior and infant development. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(s397):57–63.

Goutaudier N, Séjourné N, Bui É, Cazenave N, Chabrol H. L’accouchement prématuré: une naissance traumatique ? Symptômes De stress posttraumatique et variables associées. Gynécologie Obstétrique Fertil. 2014;42(11):749–54.

Borghini A, Nix CM. Traumatisme parental et conséquences lors d’une naissance prématurée. Contraste 14 avr. N° 2015;41(1):65–84.

Fernandes DV, Canavarro MC, Moreira H. The mediating role of parenting stress in the relationship between anxious and depressive symptomatology, mothers’ perception of infant temperament, and mindful parenting during the Postpartum Period. Mindfulness. 2021;12(2):275–90.

Penn AA, Gressens P, Fleiss B, Back SA, Gallo V. Controversies in preterm brain injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;92:90–101.

Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(1):110–24.

Back SA. Brain Injury in the Preterm Infant: New Horizons for Pathogenesis and Prevention. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;53(3):185–92.

Anderson PJ, Doyle LW. Executive functioning in school-aged children who were born very Preterm or with extremely low Birth Weight in the 1990s. Pediatr. 2004;114(1):50–7.

Arpi E, Ferrari F. Preterm birth and behaviour problems in infants and preschool-age children: a review of the recent literature. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(9):788–96.

Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, Hennessy E, Wolke D, Marlow N. Psychiatric disorders in extremely Preterm children: Longitudinal finding at Age 11 years in the EPICure study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(5):453–463e1.

MSc HM, Pitchford NJ, Hagger MS, Marlow N. Development of executive function and attention in Preterm children: a systematic review. Dev Neuropsychol. 2009;34(4):393–421.

Baron IS, Kerns KA, Müller U, Ahronovich MD, Litman FR. Executive functions in extremely low birth weight and late-preterm preschoolers: effects on working memory and response inhibition. Child Neuropsychol. 2012;18(6):586–99.

Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJS. Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of School-Aged Children Who Were Born PretermA Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288(6):728–37.

Sun J, Mohay H, O’Callaghan M. A comparison of executive function in very preterm and term infants at 8 months corrected age. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(4):225–30.

López-Maestro M, Sierra-Garcia P, Diaz-Gonzalez C, Torres-Valdivieso MJ, Lora-Pablos D, Ares-Segura S, et al. Quality of attachment in infants less than 1500 g or less than 32weeks. Related factors. Early Hum Dev. 2017;104:1–6.

Gangi S, Dente D, Bacchio E, Giampietro S, Terrin G, De Curtis M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of premature birth neonates. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2013;82:882–5.

Brunson E, Thierry A, Ligier F, Vulliez-Coady L, Novo A, Rolland AC, et al. Prevalences and predictive factors of maternal trauma through 18 months after premature birth: a longitudinal, observational and descriptive study. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246758.

Nix CM, Forcada-Guex M, Borghini A, Pierrehumbert B, Ansermet F. Prématurité, vécu parental et relations parents/enfant: éléments cliniques et données de recherche. Psychiatr Enfant. 2009;52(2):423–50.

Tarabulsy GM, Larose S. Attachement et développement: Le rôle Des premières relations dans le développement humain. PUQ; 2000. p. 421.

Pignol J, Lochelongue V, Fléchelles O. Peau à peau: un contact crucial pour le nouveau-né. Spirale. 2008;46(2):59–69.

Als H, Lawhon G, Duffy FH, McAnulty GB, Gibes-Grossman R, Blickman JG. Individualized Developmental Care for the very low-birth-weight Preterm Infant: Medical and Neurofunctional effects. JAMA. sept 1994;21(11):853–8.

Kleberg A, Westrup B, Stjernqvist K, Lagercrantz H. Indications of improved cognitive development at one year of age among infants born very prematurely who received care based on the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP). Early Hum Dev. 2002;68(2):83–91.

Herizchi S, Bagher Hosseini MBH, Ghoreishizadeh M. The impact of kangaroo-mother care on postpartum depression in mothers of premature infants. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2017;5(4):312–7.

Sweeney S, Rothstein R, Visintainer P, Rothstein R, Singh R. Impact of kangaroo care on parental anxiety level and parenting skills for preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Neonatal Nurs. 2017;23(3):151–8.

Cadet IG. Impact Du massage sur les fonctions physio et psychologiques des bébés nés prématurément et sur leur développement. 2015 [cité 15 nov 2021]; Disponible sur: https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/25807.

Jefferies A. Société canadienne de pédiatrie, Comité d’étude Du Foetus et du nouveau-né. La méthode kangourou pour le nourrisson prématuré et sa famille. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(3):144–6.

Gholami A, F K, Z G. M A, N R. Comparison of the Effect of Kangaroo Care and Infant Massage on the Level of Maternal Anxiety and Neonatal Pain. 1 janv 2021;23(0011):90–7.

Karimi F, Abolhassani M, Ghasempour Z, Gholami A, Rabiee N. Comparing the Effect of Kangaroo Mother Care and Massage on Preterm Infant Pain score, stress, anxiety, Depression, and stress coping strategies of their mothers. Int J Pediatr. 2021;9(10):14508–19.

White-Traut RC, Nelson MN, Silvestri JM, Vasan U, Littau S, Meleedy-Rey P, et al. Effect of auditory, tactile, visual, and vestibular intervention on length of stay, alertness, and feeding progression in preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44(2):91–7.

White-Traut RC, Nelson MN, Silvestri JM, Patel M, Berbaum M, Gu G, et al. Developmental Patterns of Physiological Response to a multisensory intervention in extremely premature and high‐risk infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(2):266–75.

Guzzetta A, D’acunto MG, Carotenuto M, Berardi N, Bancale A, Biagioni E, et al. The effects of preterm infant massage on brain electrical activity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(s4):46–51.

Mokaberian M, Noripour S, Sheikh M, Mills PJ. Examining the effectiveness of body massage on physical status of premature neonates and their mothers’ psychological status. Early Child Dev Care. oct 2022;26(14):2311–25.

Procianoy RS, Mendes EW, Silveira RC. Massage therapy improves neurodevelopment outcome at two years corrected age for very low birth weight infants. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(1):7–11.

Ochandorena-Acha M, Terradas-Monllor M, López Sala L, Cazorla Sánchez ME, Fornaguera Marti M, Muñoz Pérez I, et al. Early Physiotherapy Intervention Program for Preterm Infants and parents: a Randomized, single-blind clinical trial. Child. 2022;9(6):895.

Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Six theories of child development: revised formulations and current issues. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1992. pp. 187–249.

Graham AM, Marr M, Buss C, Sullivan EL, Fair DA. Understanding vulnerability and adaptation in early Brain Development using Network Neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2021;44(4):276–88.

Karmiloff-Smith A. Preaching to the Converted? From constructivism to Neuroconstructivism. Child Dev Perspect. 2009;3(2):99–102.

Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health. 2019;15:1745506519844044.

Field T. Postnatal anxiety prevalence, predictors and effects on development: a narrative review. Infant Behav Dev. 2018;51:24–32.

Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M, Pierrehumbert B, Jaunin L, Borghini A, Ansermet F. Prematurity, maternal stress and mother–child interactions. Early Hum Dev. 2004;79(2):145–58.

Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M. Perinatal Assessment of Infant, Parents, and parent-infant relationship: Prematurity as an Example. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin. 2009;18(3):545–57.

Carolina T, Isabel S, Judi M. Controlling parenting behaviors in parents of children born Preterm: a Meta-analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatric. 2020;41(3):230–41.

DESJARDINS N, DUMONT J, LAVERDURE J. POISSANT J. Les services intégrés en périnatalité et pour la petite enfance à L’intention Des familles vivant en contexte de vulnérabilité: guide pour Soutenir Le développement De L’attachement sécurisant De La Grossesse à 1 an. Québec: Santé et services sociaux Québec; 2005. p. 177.

Gueron-Sela N, Atzaba-Poria N, Meiri G, Marks K. The Caregiving Environment and Developmental outcomes of Preterm infants: Diathesis stress or Differential Susceptibility effects? Child Dev. 2015;86(4):1014–30.

Le Sourn-Bissaoui S, Deleau M. Discours Maternel et compréhension des états mentaux émotionnels et cognitifs à 3 ans. Enfance. 2001;53(4):329–48.

Letourneau NL, Dennis CL, Benzies K, Duffett-Leger L, Stewart M, Tryphonopoulos PD, et al. Postpartum Depression is a Family Affair: addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(7):445–57.

Pierrehumbert B, Nicole A, Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M, Ansermet F. Parental post-traumatic reactions after premature birth: implications for sleeping and eating problems in the infant. Arch Dis Child - Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(5):F400–4.

Pajulo M, Savonlahti E, Sourander A, Piha J, Helenius H. Maternal representations, depression and interactive behaviour in the postnatal period: a brief report. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2004;22(2):91–8.

Apter G, Nestour AL. Repérages et risques de maltraitance en période périnatale. Médecine Thérapeutique Pédiatrie. 2011;14(1):47–52.

Feldman R, Rosenthal Z, Eidelman AI. Maternal-Preterm Skin-to-Skin Contact Enhances Child Physiologic Organization and Cognitive Control across the First 10 years of life. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(1):56–64.

Rao P, Bethou RR, Bhat A. V, C P. Does Kangaroo Mother Care Reduce Anxiety in Postnatal Mothers of Preterm Babies? – A Descriptive Study from a Tertiary Care Centre in South India. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 7 août 2019;17(1):42–5.

Erduran B, Yaman Sözbir Ş. Effects of intermittent kangaroo care on maternal attachment, postpartum depression of mothers with preterm infants. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2022;0(0):1–10.

Mörelius E, Örtenstrand A, Theodorsson E, Frostell A. A randomised trial of continuous skin-to-skin contact after preterm birth and the effects on salivary cortisol, parental stress, depression, and breastfeeding. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91(1):63–70.

Afand N, Keshavarz M, Fatemi NS, Montazeri A. Effects of infant massage on state anxiety in mothers of preterm infants prior to hospital discharge. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(13–14):1887–92.

Spielberger. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (form Y). Palo Alto, Ca: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS‐21). : Construct validity and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample - Henry – 2005 - British Journal of Clinical Psychology - Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cité 5 avr 2023]. Disponible sur: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1348/014466505X29657.

Adouard F, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NMC, Golse B. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in a sample of women with high-risk pregnancies in France. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2005;8(2):89–95.

Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. Beck depression inventory (BDI). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–71.

Zelkowitz P, Papageorgiou A, Bardin C, Wang T. Persistent maternal anxiety affects the interaction between mothers and their very low birthweight children at 24 months. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85(1):51–8.

Guittard C, Novo A, Eutrope J, Gower C, Barbe C, Bednarek N et al. Protocol for a prospective multicenter longitudinal randomized controlled trial (CALIN) of sensory-tonic stimulation to foster parent child interactions and social cognition in very premature infants. Front Pediatr. 2023;10:913396.

Guédeney N, Beckechi V, Barbey-Mintz AS, Saive AL. L’implication Des parents en néonatologie et le processus de caregiving. Devenir. 2012;24(1):9–34.

Cyranowski JM, Hofkens TL, Frank E, Seltman H, Cai HM, Amico JA. Evidence of Dysregulated Peripheral Oxytocin Release among Depressed Women. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(9):967.

Skrundz M, Bolten M, Nast I, Hellhammer DH, Meinlschmidt G. Plasma oxytocin concentration during pregnancy is associated with development of Postpartum Depression. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;36(9):1886–93.

Ozsoy S, Esel E, Kula M. Serum oxytocin levels in patients with depression and the effects of gender and antidepressant treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2009;169(3):249–52.

Scantamburlo G, Hansenne M, Fuchs S, Pitchot W, Maréchal P, Pequeux C, et al. Plasma oxytocin levels and anxiety in patients with major depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(4):407–10.

Sue Carter C, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Kramer KM, Ziegler TE, White-Traut R, Bello D, et al. Oxytocin Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1098(1):312–22.

Feldman R, Gordon I, Schneiderman I, Weisman O, Zagoory-Sharon O. Natural variations in maternal and paternal care are associated with systematic changes in oxytocin following parent–infant contact. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35(8):1133–41.

Glover V, Onozawa K, Hodgkinson A. Benefits of infant massage for mothers with postnatal depression. Semin Neonatol. 2002;7(6):495–500.

Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1389–98.

Labuschagne I, Phan KL, Wood A, Angstadt M, Chua P, Heinrichs M, et al. Oxytocin attenuates Amygdala Reactivity to fear in generalized social anxiety disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35(12):2403–13.

Matricardi S, Agostino R, Fedeli C, Montirosso R. Mothers are not fathers: differences between parents in the reduction of stress levels after a parental intervention in a NICU. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(1):8–14.

Handlin L, Jonas W, Petersson M, Ejdebäck M, Ransjö-Arvidson AB, Nissen E, et al. Effects of Sucking and skin-to-skin contact on maternal ACTH and cortisol levels during the Second Day Postpartum—Influence of Epidural Analgesia and Oxytocin in the Perinatal Period. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4(4):207–20.

Bello D, White-Traut R, Schwertz D, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Carter CS. An exploratory study of Neurohormonal Responses of Healthy Men to Massage. J Altern Complement Med mai. 2008;14(4):387–94.

Beck CT, Driscoll JW, Watson S. Traumatic Childbirth. Routledge; 2013. p. 270.

Davis L, Mohay H, Edwards H. Mothers’ involvement in caring for their premature infants: an historical overview. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(6):578–86.

Thomason E, Volling BL, Flynn HA, McDonough SC, Marcus SM, Lopez JF, et al. Parenting stress and depressive symptoms in postpartum mothers: bidirectional or unidirectional effects? Infant Behav Dev. 2014;37(3):406–15.

Schecter R, Pham T, Hua A, Spinazzola R, Sonnenklar J, Li D, et al. Prevalence and longevity of PTSD symptoms among parents of NICU infants analyzed across gestational age categories. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2020;59(2):163–9.

Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and Postpartum Depression in parents of infants in the neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(3):230–7.

Nugent JK, Bartlett JD, Von Ende A, Valim C. The effects of the newborn behavioral observations (NBO) system on sensitivity in mother–infant interactions. Infants Young Child. 2017;30(4):257–68.

DeMier RL, Hynan MT, Hatfield RF, Varner MW, Harris HB, Manniello RL. A measurement model of perinatal stressors: identifying risk for postnatal emotional distress in mothers of high-risk infants. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56(1):89–100.

Kawafha MM. Parental stress in the neonate intensive care unit and its association with parental and infant characteristics. J Neonatal Nurs. 2018;24(5):266–72.

Singer LT, Fulton S, Davillier M, Koshy D, Salvator A, Baley JE. Effects of infant risk status and maternal psychological distress on maternal-infant interactions during the First Year of Life. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(4):233.

Feeley N, Zelkowitz P, Cormier C, Charbonneau L, Lacroix A, Papageorgiou A. Posttraumatic stress among mothers of very low birthweight infants at 6 months after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(2):114–7.

Holditch-Davis D, Bartlett TR, Blickman AL, Miles MS. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in mothers of premature infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(2):161–71.

Rogers CE, Kidokoro H, Wallendorf M, Inder TE. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J Perinatol mars. 2013;33(3):171–6.

Cajiao-Nieto J, Torres-Giménez A, Merelles-Tormo A, Botet-Mussons F. Paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression in the first month after Childbirth: a comparison between fathers of full term and preterm infants. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:517–26.

Eddy B, Poll V, Whiting J, Clevesy M. Forgotten fathers: Postpartum Depression in men. J Fam Issues. 2019;40(8):1001–17.

Barker B, Iles JE, Ramchandani PG. Fathers, fathering and child psychopathology. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;15:87–92.

Fredriksen E, von Soest T, Smith L, Moe V. Parenting stress plays a Mediating Role in the prediction of early child development from both parents’ perinatal depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47(1):149–64.

Gentile S, Fusco ML. Untreated perinatal paternal depression: effects on offspring. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:325–32.

Ramchandani P, Psychogiou L. Paternal psychiatric disorders and children’s psychosocial development. The Lancet. 2009;374(9690):646–53.

Sethna V, Murray L, Edmondson O, Iles J, Ramchandani PG. Depression and playfulness in fathers and young infants: a matched design comparison study. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:364–70.

Putnam KT, Wilcox M, Robertson-Blackmore E, Sharkey K, Bergink V, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(6):477–85.

Tursz A. [Risk factors of Child Abuse and neglect in childhood]. Rev Prat. 2011;61(5):658–60.

Narayanan MK, Nærde A. Associations between maternal and paternal depressive symptoms and early child behavior problems: testing a mutually adjusted prospective longitudinal model. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:181–9.

Psouni E, Eichbichler A. Feelings of restriction and incompetence in parenting mediate the link between attachment anxiety and paternal postnatal depression. Psychol Men Masculinities. 2020;21:416–29.

Zelkowitz P, Na S, Wang T, Bardin C, Papageorgiou A. Early maternal anxiety predicts cognitive and behavioural outcomes of VLBW children at 24 months corrected age. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(5):700–4.

Neri E, Agostini F, Salvatori P, Biasini A, Monti F. Mother-preterm infant interactions at 3 months of corrected age: influence of maternal depression, anxiety and neonatal birth weight. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2015. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01234. [cité 5 avr 2023];6. Disponible sur:. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/.

Korja R, Savonlahti E, Ahlqvist-Björkroth S, Stolt S, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, et al. Maternal depression is associated with mother–infant interaction in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(6):724–30.

Gould JF, Di Fiore C, Williamson P, Roberts RM, Shute RH, Collins CT, et al. Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Comparing the theories when determining the outcomes for children born before 33 weeks’ gestation. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2022;224:103533.

Shah PE, Robbins N, Coelho RB, Poehlmann J. The paradox of prematurity: the behavioral vulnerability of late preterm infants and the cognitive susceptibility of very preterm infants at 36 months post-term. Infant Behav Dev. 2013;36(1):50–62.

Trumello C, Candelori C, Cofini M, Cimino S, Cerniglia L, Paciello M, et al. Mothers’ depression, anxiety, and Mental representations after Preterm Birth: a study during the infant’s hospitalization in a neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00359/full. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/. [cité 13 sept 2021];0. Disponible sur.

Webb AR, Heller HT, Benson CB, Lahav A. Mother’s voice and heartbeat sounds elicit auditory plasticity in the human brain before full gestation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(10):3152–7.

Pelc K, Daniel I, Wenderickx B, Dan B. Multicentre prospective randomised single-blind controlled study protocol of the effect of an additional parent-administered sensorimotor stimulation on neurological development of preterm infants: Primebrain. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018084.

Guillois B, Castel S, Beunard A, Blaizot X, Creveuil C, Proia-Lelouey N. Efficacité des programmes d’intervention précoce après l’hospitalisation sur le développement neurocomportemental des enfants prématurés. Arch Pédiatrie. 2012;19(9):990–7.

Canada L. and A. Item – Theses Canada [Internet]. 2022 [cité 5 avr 2023]. Disponible sur: https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/services/services-libraries/theses/Pages/item.aspx?idNumber=1132099862.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eva Gonçalves Bedulho, a master student, for her contribution to the bibliographic search and data selection, extraction and qualitative assessment.

Funding

C. Guittard’s PhD research is funded by the American Committee of the American Memorial Hospital in Reims.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CG performed the literature search in the databases, selection and quality assessment of the studies, data extraction, analysis of the results, and drafting of the manuscript.GL, JE and SC supervised all the methodology and the writing of the manuscript.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guittard, C., Eutrope, J., Caillies, S. et al. Effect of tactile and/or kinesthetic stimulation therapy of preterm infants on their parents’ anxiety and depressive symptoms: A systematic review. BMC Psychol 12, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01510-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01510-x