Abstract

Background

Although the tobacco epidemic is one of the greatest public health threats, the smoking cessation rate among Chinese adults is considerably lower. Personality information may indicate which treatments or interventions are more likely to be effective. China is the largest producer and consumer of tobacco worldwide. However, little is known about the association between smoking cessation and personality traits in China.

Aim

This study aimed to examine the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits among Chinese adults.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2018 China Family Panel Studies. Probit regression models were employed to analyze the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits stratified by sex.

Results

Lower scores for neuroticism (Coef.=-0.055, p < 0.1), lower scores for extraversion (Coef.=-0.077, p < 0.05), and higher scores for openness to experience (Coef.=0.045, p < 0.1) predicted being a successful male quitter after adjusting for demographics. Moreover, lower scores for conscientiousness (Coef.=-0.150, p < 0.1) predicted being a successful female quitter after adjusting for demographics.

Conclusion

The empirical findings suggested that among Chinese men, lower levels of neuroticism, lower levels of extraversion, and higher levels of openness to experience were associated with a higher likelihood of smoking cessation. Moreover, lower levels of conscientiousness were associated with successful smoking cessation among Chinese women. These results showed that personality information should be included in smoking cessation interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The tobacco epidemic is one of the greatest public health threats, resulting in 7.69 million deaths a year worldwide [1]. In China, 26.6% of adults aged 15 years or older were current smokers in 2018. Men (50.5%) were more likely than women (2.1%) to be current smokers [2]. Although smoking has been proven to be a significant cause of diseases such as cancers, heart diseases, stroke, lung diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [3], the smoking cessation rate (percentage of former smokers out of current and former smokers) among Chinese adults aged 15 years or older was 20.1%, and the smoking cessation rate of daily smokers was only 15.6% in 2018 [2]. Successful smoking cessation is associated with the amount of tobacco smoking, age, socioeconomic status, marital status, alcohol consumption, disease morbidity, and physiological, psychological, and behavioral factors [4,5,6,7,8]. Psychological factors include personality traits, self-control, depressive disorders, and anxiety [9, 10].

Personality traits reflect basic trait dimensions on which people differ [11]. The most widely accepted taxonomy of personality traits is the five-factor model of personality (FFM) known as the ‘Big Five’ personality traits. The FFM is a set of five trait dimensions describing most personality traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness [12]. Identification of personality traits associated with smoking initiation and successful smoking cessation may help develop tailored smoking cessation programs. The effects of personality traits on smoking initiation were similar across many studies. For example, Van Loon et al. [6], Sallis et al. [13], and Hakulinen et al. [14] found that higher levels of extraversion were positively related to smoking initiation. Hakulinen et al. [14] and Von Ah [15] reported that smoking initiation was associated with lower levels of conscientiousness.

The findings are mixed on how personality traits affect smoking cessation. For example, Van Loon et al. [6], Shadel et al. [16], and Berlin and Covey [17] found that the association between smoking cessation and personality traits was not confirmed. Hakulinen et al. [14] and Cosci et al. [18] reported that higher levels of neuroticism were negatively related to smoking cessation. Abe et al. [19] and Zvolensky et al. [20] showed that higher levels of conscientiousness were associated with smoking cessation. However, Lee et al. [21] reported the opposite; lower levels of conscientiousness were related to smoking cessation among women. Leung et al. [22] found that people with lower levels of openness to experience had a greater likelihood of quitting smoking. Stephan et al. [23] found that quitters were more likely to have higher levels of agreeableness. Gainforth et al. [24] reported that people with higher levels of extraversion had greater odds of being quitters.

The extremely low prevalence of smoking among women in China has been mainly attributed to social norms against women smoking [25]. However, women are more likely than men to have a higher risk of smoking-related morbidity and mortality and face gender-specific barriers to smoking cessation [26, 27]. Personality traits show apparent gender differences. For example, women tend to score higher than men in agreeableness, meaning women are more nurturing, tenderminded, and altruistic than men [28, 29]. Therefore, we should consider different personality patterns in male and female smokers seeking effective methods for successful smoking cessation [30].

Past studies provide substantial evidence that smoking initiation is associated with different personality traits. Some personality traits are protective factors for smoking initiation, and others are risk factors [31]. However, evidence on the association between smoking cessation and personality traits is limited. Moreover, although the association between smoking cessation and personality traits has been documented, thus far, only a few studies have analyzed this phenomenon using a nationally representative dataset. Last, as the world’s largest producer and consumer of tobacco, little is known about the association between smoking cessation and personality traits in China. The previous findings may not be applicable to the Chinese population. To fill these research gaps, the objective of this study was to examine the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits among Chinese adults using a nationally representative dataset.

Methods

Theoretical model

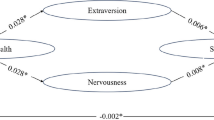

A theoretical path model of smoking cessation guided the current study [32]. The framework helps identification of potential factors affecting success in quitting smoking. A conceptual framework has been presented in Fig. 1. Demographic factors and socioeconomic status may affect smoking cessation interventions, although their effects are not in any consistent way [32, 33]. Demographic factors and socioeconomic status also significantly affect both psychological factors and health concerns [32, 34]. Psychological factors and health concerns can predict motivation, self-efficacy, and confidence to quit and also directly affect smoking cessation [32]. Abstinence motivation, self-efficacy, and confidence have been shown to play significant roles in smoking cessation [32]. It should be noted that some of the variables in the conceptual model may not be available in the CFPS. Still, this generalized framework will be helpful to ensure that all relevant variables are considered in the empirical analysis.

Data sources

The data used in this study were obtained from the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) initiated by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University in 2010. The CFPS is a general-purpose, nationally representative, longitudinal survey. A multistage probability sample proportional to size was used to select and interview households covering 25 provinces and their administrative equivalents. Five provinces or administrative equivalents (Liaoning, Shanghai, Henan, Guangdong, and Gansu) were selected to oversample populations, and the remaining twenty provinces or administrative equivalents were grouped (see Fig. 2). Each of the six CFPS subsamples was selected through three stages. The CFPS drew counties or their administrative equivalents in the first stage and then drew villages (rural areas) or resident committees (urban areas) in selected counties/districts in the second stage. Finally, households were drawn from a selected village or resident committee in the third stage. The CFPS represents 95% of the total population in the Chinese mainland [35].

The CFPS employed multi-module designs for questionnaires. Each questionnaire consisted of different modules regarding the specific situations of the individuals and households interviewed. The CFPS questionnaires include questions on demographic background, family structure/transfer, health status and physical functioning, health care utilization, insurance status, work, income, expenditure, asset ownership, community-level information, etc. The CFPS primarily conducts face-to-face interviews. When the CFPS fails to complete face-to-face interviews, telephone or web-based interviews are used as a substitute. More details on the sampling and data collection process are available in Xie and Hu [36].

The CFPS respondents are reinterviewed every two years, with the first wave in 2010 and five follow-ups in 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020. The 2018 survey included 30,593 adults (aged ≥ 16 years) who answered the survey questionnaire. From the full sample, only adults (aged ≥ 16 years) who reported former smoking or current smoking were selected (9,515 adults). After eliminating all cases with missing relevant data (173 adults), the final sample consisted of a total of 9,342 adults.

Measures

Successful Smoking cessation

Most studies on successful smoking cessation were conducted in the USA and Asian countries. In these studies, successful smoking cessation was defined as individuals who formerly smoked and stopped smoking at least 6 months, 6 to 12 months, or at least 12 months prior to the interview [37,38,39,40,41]. The current study defined successful smoking cessation as former smokers who stopped smoking cigarettes for at least 12 months. In the CFPS, each respondent was asked, ‘Have you ever smoked?’. Respondents who answered ‘Yes’ were then asked, ‘How old were you when you totally stopped smoking completely?’. The outcome variable, successful smoking cessation, was coded as 1 ‘yes’ and 0 ‘no’.

Personality traits

This study used the 15-item short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-S) to measure personality traits. In this inventory, three items assess each of the Big Five dimensions (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness). Each dimension includes positively and negatively keyed items. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After reverse-scoring the negatively keyed items and averaging the scores of each dimension, the score of each personality trait was calculated, and higher scores indicated a higher level of that trait. The BFI-S has been proven to be easy to administer, valid, and reliable [42].

Control variables

The analysis considered the following four categories of variables as control variables: (1) smoking addiction (age of smoking initiation), (2) demographic factors (age), (3) socioeconomic status (place of residence, educational attainment, marital status, medical insurance coverage, household income), and (4) health concerns (proxy indicators using self-rated health status and chronic conditions). Definitions of all the relevant variables are listed in Table 1.

Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis of successful smoking cessation was performed by considering various individual characteristics and personality traits. Statistical significance between groups was assessed through Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables.

Since the dependent variable was a binary response variable (successful smoking cessation), probit regression models were used to analyze the association of successful smoking cessation and personality traits stratified by sex. Because of different personality patterns among males and females, stratification was essential to avoid potential bias created by sex differences. The Model I was unadjusted. Age is a predictor of quit attempts and quit success in smoking cessation [43]. The control variables of adjusted models were demographic factors (Model II) and demographic factors, socioeconomic status, smoking addiction, and health concerns (Model III). The results are presented as coefficients (Coef.) along with their standard errors (SEs). All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A descriptive summary of all variables is shown in Table 1. The total sample size was 9,342; 93.76% of respondents were male, and the mean age was approximately 47 years. Approximately 60% of the respondents had at least a middle school education. A total of 7.10% of adult smokers successfully quit smoking for at least 12 months. Table 2 shows the differences between successful quitters and nonquitters according to demographics, social determinants, and health status. The results of univariable analyses indicated that successful quitters differed significantly from nonquitters in terms of their age, sex, residence, educational attainment, marital status, household income, self-rated health status, and chronic conditions.

Table 3 shows the differences between successful quitters and nonquitters according to personality traits and age of smoking initiation. Successful quitters had lower scores for extraversion (3.34 ± 0.70 vs. 3.40 ± 0.71; p < 0.05) and lower scores for conscientiousness (3.82 ± 0.72 vs. 3.87 ± 0.65, p < 0.05).

Table 4 shows successful smoking cessation associated with personality traits among Chinese men using probit models. In Model I, the coefficients of personality traits were not adjusted. Lower scores for neuroticism (Coef.=-0.055, p < 0.1) and lower scores for extraversion (Coef.=-0.075, p < 0.05) predicted being a successful male quitter. In Model II, the coefficients of personality traits were adjusted for demographics. Lower scores for neuroticism (Coef.=-0.055, p < 0.1), lower scores for extraversion (Coef.=-0.077, p < 0.05), and higher scores for openness to experience (Coef.=0.045, p < 0.1) predicted being a successful male quitter. In Model III the coefficients of personality traits were adjusted for demographics, social determinants, smoking addiction, and health concerns. Lower scores for extraversion (Coef.=-0.073, p < 0.05) predicted being a successful male quitter. Table5 shows the successful smoking cessation associated with personality traits among Chinese women using probit models. In Model I, the coefficients of personality traits were not adjusted. Lower scores for conscientiousness (Coef.=-0.167, p < 0.1) predicted being a successful female quitter. The Model II results were very similar to the Model I.

Discussion

This study examined the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits among Chinese adults. Data from a nationally representative survey were used for the analysis. The results indicated that only approximately 7% of adult smokers successfully quit for 12 months, which was consistent with the findings in the USA [44]. The adult smoking cessation rate is very low in China. Approximately 90% of adult smokers who have tried to stop smoking in the past 12 months have never received quitting assistance [2], which implies that inadequate smoking cessation programs may lead to a low cessation rate in China. Various national or international clinical guidelines suggest that smoking cessation programs include behavioral support and pharmacological treatments [45]. Knowledge regarding personality traits should be taken into consideration for individually tailored smoking cessation programs, which could lead to both improved uptake and efficacy [13]. The Chinese government needs to develop smoking cessation programs that are tailored to the needs of adult smokers. Therefore, identifying the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits will be of interest to physicians and policymakers.

We have used probit regression models to examine the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits. The results indicated that lower levels of neuroticism were associated with a higher likelihood of smoking cessation among Chinese men. However, the association became nonsignificant after adjusting for demographic factors, socioeconomic status, smoking addiction, and health concerns. Similar results have been obtained confirming the association between levels of neuroticism and smoking cessation. A cross-sectional and longitudinal individual-participant meta-analysis has shown that smoking cessation was negatively associated with neuroticism [14]. In addition, a cross-sectional study found that male smokers were much more neurotic than men who stopped smoking [46]. Neuroticism is the personality trait tendency toward anxiety, anger, self-consciousness, irritability, emotional instability, and depression [47]. An array of tobacco withdrawal symptoms accompanies smoking cessation, and these symptoms may be experienced more intensely by smokers with higher levels of neuroticism [14]. Moreover, smokers with higher levels of neuroticism respond poorly to environmental stress [48], which may increase the likelihood of smoking relapse.

We found that among Chinese men, lower levels of extraversion predicted being a successful quitter. This association was maintained after adjusting for demographic factors, socioeconomic status, smoking addiction, and health concerns. Our finding is consistent with previous Poland-based research. The cross-sectional study found that successful quitters’ facets of extraversion score were lower than current smokers [49]. However, another correlational study in the UK reported the opposite finding [24]. Extraversion is a personality trait characterized by sociability, assertiveness, high activity levels, and impulsivity [50]. Smoking is considered a highly acceptable social activity and a part of social interaction in China, especially among males [51]. The essential feature of extraversion is the disposition to enjoy social situations [52]. Therefore, cigarette refusal among smokers with higher levels of extraversion is more difficult in social situations, which may decrease the likelihood of smoking cessation.

Higher levels of openness to experience were positively associated with successful smoking cessation among Chinese men after adjusting for demographic factors. In contrast, a 7-year cohort study showed that Chinese smokers with lower levels of openness to experience had a greater likelihood of quitting smoking [22]. However, the association became nonsignificant after adjusting for demographic factors, socioeconomic status, smoking addiction, and health concerns. Individuals with higher levels of openness to experience are willing to try new things and embrace changes in their lives [53]. Although becoming a successful quitter is a challenge for smokers, smokers with higher levels of openness to experience are more likely to embrace the opportunity to remove smoking behavior from their lives and become a different version of themselves [54]. Moreover, smoking cessation services and medications are still relatively new in China. Smokers with higher levels of openness to experience are more likely to use these services and medications, which can increase quitting success rates.

Lower levels of conscientiousness were associated with successful smoking cessation among Chinese women, which was consistent with the findings in Japan [21]. However, the association became nonsignificant after adjusting for demographic factors, socioeconomic status, smoking addiction, and health concerns. Female sex was associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing depression [55]. Moreover, lower levels of conscientiousness have been found to be associated with an increased risk of depression and other mental disorders [56]. Therefore, female smokers with lower levels of conscientiousness who experience a worse mental health status are more likely to be successful quitters.

Limitations

Although the current study employed a nationally representative dataset to analyze the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits among Chinese adults, several limitations should be emphasized. First, this was a cross-sectional study based on the 2018 CFPS. It had limitations in providing causal inferences. Further longitudinal studies should be performed to track changes in smoking behavior and personality traits over time and may provide more robust evidence for the direction and mechanism of the association. Although the CFPS is a biennial longitudinal survey, the CFPS survey only collects information on personality traits in 2018. Second, the data were obtained via face-to-face or telephone interviews, and thus, limitations of all self-reported data exist, which may be subject to bias and measurement error. For example, participants may under-report their smoking behavior or over-report their success with stopping smoking, leading to inaccurate estimates of the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits. Last, although this study adjusted for a wide variety of covariates, it is possible that unknown or unmeasured confounders may explain the current findings.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to identify the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits among Chinese adults. The empirical findings suggested that among Chinese men, lower levels of neuroticism, lower levels of extraversion, and higher levels of openness to experience predicted being a successful quitter. Moreover, lower levels of conscientiousness were associated with successful smoking cessation among Chinese women. Nevertheless, the association between successful smoking cessation and personality traits among Chinese adults was not straightforward and may have varied according to sex. These results showed that personality information should be incorporated into smoking cessation interventions. The heterogeneity of smokers on several dimensions has been documented [57]. Personality information may indicate which treatments or interventions are more likely to be effective [58]. Increased attention and smoking cessation support for male smokers with higher levels of neuroticism and extraversion and encouraging the use of smoking cessation services and medications for male smokers with higher levels of openness to experience can improve the outcome of smoking cessation interventions. Female smokers with lower levels of conscientiousness have increased odds of suffering from depression, and smoking cessation interventions could effectively reduce female smokers’ risk of depression.

Data Availability

The dataset used for drafting the paper is a publicly available dataset available in the Peking University Open Research Data Platform repository. The dataset is downloadable for research purposes through the link: https://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/45LCSO.

References

GBD 2019 Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking Tobacco use and attributable Disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10292):2337–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7

World Health Organization. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). Fact sheet China 2018. (2019). https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/countries/china/2018-gats-china-factsheet-cn-en.pdf. [Accessed Dec 10, 2022].

Chan KH, Wright N, Xiao D, Guo Y, Chen Y, Du H, et al. Tobacco Smoking and risks of more than 470 Diseases in China: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(12):e1014–e26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00227-4

Osler M, Prescott E. Psychosocial, behavioural, and health determinants of successful Smoking cessation: a longitudinal study of Danish adults. Tob Control. 1998;7(3):262–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.7.3.262

Osler M, Prescott E, Godtfredsen N, Hein HO, Schnohr P. Gender and determinants of smoking cessation: a longitudinal study. Prev Med. 1999;29(1):57–62. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1999.0510

Van Loon AJ, Tijhuis M, Surtees PG, Ormel J. Determinants of Smoking status: cross-sectional data on Smoking initiation and cessation. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(3):256–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cki077

Yang JJ, Song M, Yoon HS, et al. What are the major determinants in the success of Smoking Cessation: results from the Health examinees Study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0143303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143303

Gritz ER, Nielsen IR, Brooks LA. Smoking cessation and gender: the influence of physiological, psychological, and behavioral factors. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1972;51(1–2):35–42.

Boudrez H. Psychological factors and long-term abstinence after smoking cessation treatment. J Smok Cessat. 2009;4(1):10–7. https://doi.org/10.1375/jsc.4.1.10

Rondina Rde C, Gorayeb R, Botelho C. Psychological characteristics associated with Tobacco Smoking behavior. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(5):592–601. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37132007000500016

Matthews G, Deary IJ, Whiteman MC. Personality traits. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Roccas S, Sagiv L, Schwartz SH, Knafo A. The big five personality factors and personal values. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(6):789–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202289008

Sallis HM, Davey Smith G, Munafò MR. Cigarette Smoking and personality: interrogating causality using mendelian randomisation. Psychol Med. 2019;49(13):2197–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718003069

Hakulinen C, Hintsanen M, Munafò MR, Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Batty GD, et al. Personality and Smoking: individual-participant meta-analysis of nine cohort studies. Addiction. 2015;110(11):1844–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13079

Von Ah D, Ebert S, Ngamvitroj A, Park N, Kang DH. Factors related to cigarette Smoking initiation and use among college students. Tob Induc Dis. 2005;3(1):27–40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1617-9625-3-1-27

Shadel WG, Cervone D, Niaura R, Abrams DB. Investigating the big five personality factors and Smoking: implications for assessment. J Psychopathol Behav. 2004;26(3):185–91. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000022111.13381.0c

Berlin I, Covey LS. Pre-cessation depressive mood predicts failure to quit Smoking: the role of coping and personality traits. Addiction. 2006;101(12):1814–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01616.x

Cosci F, Corlando A, Fornai E, Pistelli F, Paoletti P, Carrozzi L. Nicotine dependence, psychological distress and personality traits as possible predictors of smoking cessation. Results of a double-blind study with nicotine patch. Addict Behav. 2009;34(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.08.003

Abe S, Oshio A, Kawamoto T, Ito H, Hirashima T, Tsubota Y, et al. Smokers are extraverted in Japan: Smoking habit and the big five personality traits. SAGE Open. 2019;9(3):2158244019859956. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440198599

Zvolensky MJ, Taha F, Bono A, Goodwin RD. Big five personality factors and cigarette Smoking: a 10-year study among US adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;63:91–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.02.008

Lee C, Gao M, Ryff CD. Conscientiousness and Smoking: do cultural context and gender matter? Front Psychol. 2020;11:1593. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01593

Leung DY, Au DW, Lam TH, Chan SS. Predictors of long-term abstinence among Chinese smokers following treatment: the role of personality traits. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(9):5351–54. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.9.5351

Stephan Y, Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Caille P, Terracciano A. Cigarette Smoking and personality change across adulthood: findings from five longitudinal samples. J Res Pers. 2019;81:187–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.06.006

Gainforth HL, Aujla SY, Beard E, Croghan E, West R. Associations between practitioner personality and client quit rates in smoking cessation behavioural support interventions. J Smok Cessat. 2018;13(2):103–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsc.2017.10

Sansone N, Yong HH, Li L, Jiang Y, Fong GT. Perceived acceptability of female Smoking in China. Tob Control. 2015;24(Suppl 4):48–54. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052380

Allen AM, Oncken C, Hatsukami D. Women and Smoking: the effect of gender on the epidemiology, health effects, and cessation of Smoking. Cur Addict Rep. 2014;1:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-013-0003-6

Dieleman LA, van Peet PG, Vos HM. Gender differences within the barriers to smoking cessation and the preferences for interventions in primary care a qualitative study using focus groups in the Hague, the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e042623. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042623

Schmitt DP, Long AE, McPhearson A, O’Brien K, Remmert B, Shah SH. Personality and gender differences in global perspective. Int J Psychol. 2017;52(Suppl 1):45–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12265

Weisberg YJ, Deyoung CG, Hirsh JB. Gender differences in personality across the ten aspects of the big five. Front Psychol. 2011;2:178. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00178

Piñeiro B, López-Durán A, Fernández D, Río E, Martínez U, Becoña E. Gender differences in personality patterns and Smoking status after a Smoking cessation treatment. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:306. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-306

Yee Hway Ann A, Yoke Yuen SL, Chong Wee M, Gan CK, Mogan Mohan S, Mahadhir MAHB. (2022). Personality trait and associate factors among smokers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Use. 2022; 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2022.2120426

Manfredi C, Cho YI, Crittenden KS, Dolecek TA. A path model of smoking cessation in women smokers of low socio-economic status. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(5):747–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl155

Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Reitzel LR, Costello TJ, Cofta-Woerpel L, Li Y, Mazas CA, Vidrine JI, Cinciripini PM, Greisinger AJ, Wetter DW. Mechanisms linking socioeconomic status to smoking cessation: a structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2010;29(3):262–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019285

Harwood GA, Salsberry P, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Cigarette Smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(4):361–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00645.x

Xie Y, Lu P. The sampling design of the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chin J Sociol. 2015;1(4):471–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X15614

Xie Y. An introduction to the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chin Sociol Rev. 2014;47(1):3–29. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555470101.2014.11082908

Walton K, Wang TW, Prutzman Y, Jamal A, Babb SD. Characteristics and correlates of recent successful Cessation among adult cigarette smokers, United States, 2018. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:200173. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200173

Henley SJ, Asman K, Momin B, Gallaway MS, Culp MB, Ragan KR, et al. Smoking cessation behaviors among older US adults. Prev Med Rep. 2019;16:100978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100978

Bassett JC, Matulewicz RS, Kwan L, McCarthy WJ, Gore JL, Saigal CS. Prevalence and correlates of successful Smoking cessation in Bladder cancer survivors. Urology. 2001;153:236–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.12.033

Sornpaisarn B, Parvez N, Chatakan W, Thitiprasert W, Precha P, Kongsakol R, et al. Methods and factors influencing successful Smoking cessation in Thailand: a case-control study among smokers at the community level. Tob Induc Dis. 2002;20:1–12. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/150345

Kim YJ. Predictors for successful Smoking cessation in Korean adults. Asian Nurs Res. 2014;8(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2013.09.004

Zhang X, Wang MC, He L, Jie L, Deng J. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese big five personality Inventory-15. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0221621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221621

Arancini L, Borland R, Le Grande M, Mohebbi M, Dodd S, Dean OM, Berk M, McNeill A, Fong GT, Cummings KM. Age as a predictor of quit attempts and quit success in smoking cessation: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country survey (2002-14). Addiction. 2021;116(9):2509–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15454

Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, Cullen KA, Day H, Willis G, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation indicators among adults -United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1013–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2

Sutherland G. Current approaches to the management of smoking cessation. Drugs. 2002;62(Suppl 2):53–61. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200262002-00006

Patton D, Barnes EG, Murray PR. Personality characteristics of smokers and ex-smokers. Pers Individ Differ. 1993;15(6):653–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(93)90007-P

Leary MR, Hoyle RH. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009.

Widiger TA, Oltmanns JR. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):144–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20411

Buczkowski K, Basinska MA, Ratajska A, Lewandowska K, Luszkiewicz D, Sieminska A. Smoking status and the five-factor model of personality: results of a cross-sectional study conducted in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020126

Lucas RE, Baltes PB. Int Encyclopedia Social Behav Sci Pergamon. 2001;.5202–05p.

Ma GX, Shive SE, Ma XS, Toubbeh JI, Tan Y, Lan YJ, et al. Social influences on cigarette Smoking among Mainland Chinese and Chinese americans: a comparative study. Am J Health Stud. 2013;28(1):12–20.

Lucas RE, Diener E. Understanding extraverts’ enjoyment of social situations: the importance of pleasantness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(2):343–56. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.343

LePine JA. Team adaptation and postchange performance: effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(1):27–39. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.27

Sullivan G, Based on Your Personality. How to Quit Smoking, (2019). https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/acquainted-the-night/201912/how-quit-smoking-based-your-personality [Accessed Dec 20, 2022].

Goodwin RD, Gotlib IH. Gender differences in depression: the role of personality factors. Psychiatry Res. 2004;126(2):135–42.

Tellegen A, Lykken DT, Bouchard TJ Jr, Wilcox KJ, Segal NL, Rich S. Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1031–9.

Poland BD, Cohen JE, Ashley MJ, Adlaf E, Ferrence R, Pederson LL, Bull SB, Raphael D. Heterogeneity among smokers and non-smokers in attitudes and behaviour regarding Smoking and Smoking restrictions. Tob Control. 2000;9(4):364–71. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.9.4.364

del Río EF, López-Durán A, Rodríguez-Cano R, Martínez Ú, Martínez-Vispo C, Becoña E. Facets of the NEO-PI-R and smoking cessation. Pers Individ Differ. 2015; 80(2015): 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.030

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was funded by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Natural Science Fund (2021BS07006), Youth Development Program at Inner Mongolia Medical University (YKD2021QN016) and Inner Mongolia Medical University Duxue Talent Program (ZY0301017). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WJ, BX, and CL collaboratively designed the study, developed the methodology, and interpreted the results. CL and WJ led the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. WJ, CL, BX, and LZ made important contributions to revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Peking University Biomedical Ethics Review Committee (IRB00001052-14010). All participants (including minor and illiterate) provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Informed consent was obtained from their parents/ Legal guardians. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for research ethics.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, W., Xian, B., Zhao, L. et al. Association between personality traits and smoking cessation among Chinese adults. BMC Psychol 11, 398 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01442-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01442-6