Abstract

Background

The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) is a widely used tool for individuals to self-report their self-esteem; however, the factorial structures of translated versions of the RSES vary across different languages. This study aimed to validate the Chinese version of the RSES in the Chinese mainland using a longitudinal design.

Methods

A group of healthcare university students completed the RSES across three waves: baseline, 1-week follow-up, and 15-week follow-up. A total of 481 valid responses were collected through the three-wave data collection process. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the baseline data to explore the potential factorial structure, while confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the follow-up data to determine the best-fit model. Additionally, the cross-sectional and longitudinal measurement invariances were tested to assess the measurement properties of the RSES for different groups, such as gender and age, as well as across different time points. Convergent validity was assessed against the Self-Rated Health Questionnaire (SRHQ) using Spearman’s correlation. Internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients, while test–retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient.

Results

The results of EFA revealed that Items 5, 8, and 9 had inadequate or cross-factor loadings, leading to their removal from further analysis. Analysis of the remaining seven items using EFA suggested a two-factor solution. A comparison of several potential models for the 10-item and 7-item RSES using CFA showed a preference for the 7-item form (RSES-7) with two factors. Furthermore, the RSES-7 exhibited strict invariance across different groups and time points, indicating its stability and consistency. The RSES-7 also demonstrated adequate convergent validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability, which further supported its robustness as a measure of self-esteem.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that the RSES-7 is a psychometrically sound and brief self-report scale for measuring self-esteem in the Chinese context. More studies are warranted to further verify its usability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Self-esteem is considered to be a set of thoughts and feelings about one’s self-worth and importance; that is, a global positive or negative attitude towards the self [1]. Positive self-esteem is often regarded as a protective factor for mental health and a buffer against adverse events [2, 3]. Conversely, negative self-esteem is seen as a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and social problems [4,5,6,7,8]. Arguably, self-esteem is a highly crucial psychological need that requires the attention and protection of each individual as well as wider society; therefore, it is essential to gain a deeper understanding of its subjective evaluation.

To date, the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), developed in 1965 [1], is one of the most accepted and globally used scales for measuring self-esteem. It has been translated into more than 28 languages and used in 53 countries and regions, and this data continues to grow [9]. Rosenberg proposed that people with high self-esteem tend to be self-respecting, consider themselves worthy, and appreciate their own merits while recognizing their faults. People with low self-esteem lack respect for themselves and consider themselves to be unworthy, inadequate, or seriously deficient [10, 11]. Regarding its measurement, unlike many other scales that assess self-esteem, the RSES is concise and convenient [9, 12]. The low number of items, short completion time, and reduced chance of respondent tiredness facilitate its ease of use in various cohorts.

The RSES has been translated into numerous languages since it was first developed [13,14,15]. Even though many studies have supported the psychometric properties of the different versions, such as the Spanish, German, Dutch, and Japanese versions [16,17,18], there is ongoing controversy about whether the RSES is unidimensional or multidimensional and whether the difference between positive and negative self-esteem is due to language effects [19]. In cross-cultural validation, many studies have reported low factor loadings for some items, an unstable factor structure, and a cross-cultural misfit [20,21,22,23]. More importantly, cultural differences between the East and West, caused by different understandings of negatively worded items, may have confined the cross-cultural comparisons [9].

Several studies have examined the psychometric properties of different Chinese versions of the RSES. In 1993, the first translation in simplified Chinese resulted in a version of the RSES that showed poor reliability [24]. In that study, Item 8 (“I wish I could have more respect for myself”) resulted in a negative item-total correlation due to translation bias and cultural differences [24]. Other researchers have discussed the removal of Item 8 yet failed to reach a consensus [25,26,27]. In 1997, a version in traditional Chinese was created in Hong Kong, China, to provide a self-esteem instrument for Cantonese-speaking people [28]. Given the unsatisfactory reliability (N = 1101, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.686) of this version, scholars in Macau, China, modified Items 2, 3, 7, and 8 to adapt the RSES to the local culture [29]. The adaptations resulted in a version with improved scale reliability, although Item 8 retained suboptimal psychometric properties [29]. After comparison, we chose the traditional Chinese adaptation for use in the current study, which was conducted in the Chinese mainland after the traditional Chinese adaptation was converted directly into simplified Chinese.

Since societal processes influence self-esteem, it is crucial to assess whether different versions of the RSES work in a similar way across different contexts and generations. Thus, a longitudinal study focusing on the utility of the simplified Chinese adaptation of the RSES within the Chinese mainland context can provide new evidence to the extant literature and ongoing exploration of the Chinese version. The goal of this study, which was with a Chinese healthcare students cohort, was mainly twofold: (i) evaluate the main psychometric properties of the scale—structural validity, convergent validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability; (ii) test the cross-sectional and longitudinal measurement invariance.

Methods

Study design and procedure

The study used a three-wave longitudinal observational design among healthcare students in Hangzhou, China. The protocol adhered strictly to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to ensure the accurate, high-quality presentation of the research [30].

Minimum sample size guidelines recommend 15 participants per variable; hence, as there are 10 items in the RSES, the required sample was 150 [31]. Using a stratified random sampling method, healthcare students in the medical department of one university in Hangzhou were randomly selected to participate in a paper-and-pencil survey from December 2020 to April 2021. Before the survey, we contacted the leaders of the target classes to determine when the respondents would have free time and subsequently conducted the survey in the classroom during breaks. We collected student ID numbers; this step was for matching the same individual across three waves. A total of 637 healthcare students participated in the initial baseline assessment. One week later, 616 students underwent the re-assessment wave [32, 33]. After a 15-week interval, 540 students completed the third assessment. There data from 512 participants were successfully matched across three waves; after participants with missing data were removed from the dataset, 481 individuals were left for the subsequent analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hangzhou Normal University Division of Health Sciences, China (Reference No. 20190076). The data collection process with prior informed consent was undertaken anonymously to protect individual privacy rights.

Measures

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The RSES [1] consists of five positively worded items (1, 3, 4, 7, 10) and five negatively worded items (2, 5, 6, 8, 9), and serves as one of the most broadly used instruments for global self-esteem. The scale was initially designed to be unidimensional, yet numerous studies worldwide have revealed that it may be multidimensional, with both positive and negative self-esteem dimensions. Positively worded items are given a score from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Negatively worded are reverse scored, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total sum score for all 10 items ranges from 10 to 40, with higher scores representing higher self-esteem. The scale used in this study was the traditional Chinese language adaptation, developed in Macau, China [29], that was converted into simplified Chinese for the purposes of this study.

Self-Rated Health Questionnaire

The Self-Rated Health Questionnaire (SRHQ) [34] is a two-item scale that assesses physical and psychological health. Participants reported their health status on a five-point Likert scale with varying response categories (1 = excellent, 2 = good, 3 = average, 4 = poor, 5 = extremely poor), giving a total sum score ranging from 2 to 10. Higher scores represent poorer overall self-rated health. The scale has shown stable psychometric properties in recent measurements with large samples (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.706) [34].

Sociodemographic description

The following variables were also collected: gender (0–male, 1–female), age (mean = 19.688, standard deviation = 1.329), home location (0–urban, 1–rural, 2–suburban), single-child status (0–yes, 1–no), academic year (0–first year, 1–second year, 2–third year), family income (0– < 10 000 CNY, 1– ≥ 10 000 CNY), part-time employment (0–yes, 1–no), leisure-time sports involvement (0–yes, 1–no).

Statistical analysis

Measurement properties were assessed based on the COnsensus-based Standards for selecting health Measurement INstruments guidelines (COSMIN) [35, 36]. EpiData (version 3.1), JASP (version 0.16.1), and R (version 4.1.2) software were used for database creation, data organization, and data analysis, respectively. Missing data analysis was performed using the “naniar” package and showed that out of the 512 participants who completed the questionnaires on all three occasions, 481 (93.945%) had no missing values, and 31 (6.055%) had missing values. The missing data rate for the RSES items and sample variables ranged from 0.195% to 1.758%. Listwise deletion was applied since the level of missing data was negligible in this study [37]. The multivariate normality test of scores was performed using the “MVN v.5.9” package [38].

Structural validity

To assess the structural validity of the RSES, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on the baseline, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the 1-week and 15-week follow-ups using the “lavaan v.0.6–9” package [39]. Before EFA, item-total correlation, two tests, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO, KMO ≥ 0.800) and Bartlett’s test (P < 0.001), were implemented to examine the factorability of the data [40, 41]. EFA with the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) method, Promax rotation, and parallel analysis was used for the factor extraction. When the target-loading was less than 0.450, the cross-loading was higher than 0.320, or the gap between the target-loading and cross-loading was lower than or equal to 0.200, the item was considered for removal [41, 42].

Given the ordinal nature of the variables, in the CFA we chose the WLSMV estimator, which shows less bias in standard errors and yields more accurate factor loadings [43]. Fit indices were considered to be acceptable when they were within the following thresholds: Chi-square/degree of freedom (χ2/df) = 2‒3, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.900, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.900, standardized root mean residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.080, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.080 [37, 44, 45].

Measurement invariance

The measurement invariance of the RSES was examined by comparing five nested models (i.e., configural, threshold, metric, scalar, and strict invariance model) with progressively tighter restrictions using the “semTools v.0.5–5” package [46]. A range of tests were conducted: configural invariance tests assessed whether the constellation of items and factors was the same across groups or time; threshold invariance tests assessed whether the association of the underlying (latent) continuous score with the ordinal numbers of the items was the same across groups or time; metric invariance tests whether the factor loadings of each item were the same across groups or time; scalar invariance tests assessed whether the item intercepts were the same across groups or time; and finally, strict invariance was used to examine whether the error variance (residuals) of each item were the same across groups or time.

To comprehensively examine the scale’s usability, we analyzed the cross-sectional measurement invariances (CMIs) in the best-fit scale model across gender and age. This was because previous research has shown different in self-esteem between genders and age groups [47]. We also examined the measurement invariance across home location, single-child status, academic year, family income, part-time employment, and leisure-time sports involvement to explore their potential influence (if any) on self-esteem measurement.

To test for response shifts, through longitudinal CFA, the longitudinal measurement invariances (LMIs) were analyzed across three waves: baseline, 1-week follow-up, and 15-week follow-up. Measurement invariance was assumed when two of the three following indices met the criteria: ΔCFI ≤ 0.010, ΔTLI ≤ 0.010, ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 [48,49,50].

Convergent validity

Spearman’s correlation was used to examine convergent validity by testing the correlation between two relevant constructs. Given that self-esteem measured by the RSES has been associated with self-rated mental health using the SRHQ, a moderately strong correlation (-0.500 ≤ r ≤ -0.300) between the SRHQ and RSES was hypothesized. Meanwhile, the average variance extracted (AVE; AVE > 0.500) and construct reliability (CR; CR > 0.700) were also integrated to assess convergent validity [51].

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the subscale and total scores for the RSES and SRHQ across the three waves was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (α) and MacDonald’s omega (ω) using the “ufs v.0.4.5” package in R [52, 53]. Cronbach’s α is the most commonly used coefficient; however, in consideration of its reported imperfections, MacDonald’s ω was calculated simultaneously to provide more objective confidence estimates [53]. Both α and ω were considered acceptable when ≥ 0.700 [36, 53,54,55].

Test–retest reliability

Test–retest reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), with ICC ≥ 0.700 considered as the preferable value [56]. Standard error of measurement was also computed using “standard deviation × sqrt (1-ICC)”. The test–retest reliability was performed using the “irr v.0.84.1” package in R [57].

Results

Sample characteristics

The final sample size for this study was 481. The participant characteristics and the RSES total scores for the three measurement waves are presented in Supplementary Material, Table S1.

Structural validity

The results of the KMO test (KMO = 0.900) and Bartlett’s test (χ2 = 1976.017, df = 45, P < 0.001) for the 10-item RSES (RSES-10) suggested that the scale was suitable for factor analysis. EFA of the baseline data revealed two factors (see Table 1). However, the factor loading for Item 8 (“I wish I could have more respect for myself”) was below 0.450; hence, it was removed. Subsequent EFA of the remaining nine items suggested removing Item 5 (“I feel I do not have much to be proud of”) due to a factor loading below 0.450, and then removing Item 9 (“All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure”) due to a gap between the target-loadings and cross-loadings of below 0.200. The results of the 7-item RSES (RSES-7) without Items 5, 8, and 9 (KMO = 0.848; χ2 = 1336.556, df = 21, P < 0.010) revealed two factors and accounted for 57.6% of the total variance. The factor loadings for the positive (0.577 to 0.812) and negative (0.597 to 1.052) subscales were acceptable.

As the factor loading of Item 6 exceeded one, we also explored another model without Item 6. Again, a two-factor solution was found. However, the negative factor only comprised one item (Item 2). After removing this single item and rerunning the EFA, the five positively worded items loaded onto a single factor and explained 50% of the total variance (see Supplementary Material, Table S2).

Several CFAs were then conducted to examine the following models for the RSES-10 and RSES-7: a one-factor model, a two-factor model (with positive and negative factors), a second-order factor model (with a general factor of self-esteem accounting for the two specific factors), and a two-factor model for acquiescence (with a general factor of self-esteem and a method factor of acquiescence). The same analyses were conducted with the data collected from the 1-week follow-up and 15-week follow-up. As can be seen in Table 2, the two-factor model was superior to the other three models for both the RSES-10 and RSES-7. The same pattern of results was also observed in both follow-up datasets. Finally, inspection of the two-factor RSES-10 and RSES-7 models demonstrated found that the RSES-7 showed a better fit, and the two-factor model for acquiescence indicated that the difference between the two models was not caused by the method. In other words, the results suggest that the 7-item simplified Chinese language RSES with two factors was the preferable model.

Measurement invariance

Cross-sectional measurement invariance

Table 3 summarizes the CMI results for the RSES-7 across eight subgroups (e.g., gender, age, family income) for the three waves. The results showed that at least two of the three indices (ΔCFI, ΔTLI, and ΔRMSEA) in each subgroup met the suggested criteria, indicating that there were negligible changes between two adjacent models [58]. Thus, the threshold, metric, scalar, and strict invariance models were all supported for the RSES-7.

We also examined the CMI results for the RSES-10 (see Supplementary Material, Table S3) for comparison. The strict model was achieved for both the 1-week follow-up and 15-week follow-up data. But for the baseline data, the academic year, part-time employment, and sports engagement subgroups showed the measurement invariance only in the threshold model.

Longitudinal measurement invariance

Table 4 shows the LMI results across the three waves (i.e., baseline, 1-week follow-up, 15-week follow-up) for the RSES-7 and RSES-10. It was found that all the indicators met the criteria, and strict measurement invariance was held for both models, suggesting that our participants’ self-esteem scores remained consistent across the 15 weeks of the study.

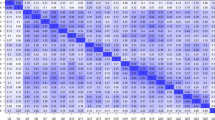

Convergent validity

The left half of Fig. 1 shows the factor-factor and factor-total score correlations for the RSES-7 (AVE: 0.640‒0.866, CR: 0.784‒0.875, see the Supplementary Material, Table S4, for more details), and the right half shows the correlation between the RSES-7 and SRHQ scores measured at the three waves. The factors of the RSES-7 were positively correlated with each other as well as with the total score. The weakest relationship was observed between the negative factor score measured at baseline and the positive factor score measured at the third wave (r = 0.414), while the strongest relationship was found between the positive factor score and the total score of the RSES measured at baseline (r = 0.909). In addition, the RSES-7 scores were negatively associated with the SRHQ scores, ranging from -0.205 to -0.500. Similar results were also documented for the RSES-10 (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1, for more details).

Spearman inter‒factor, factor‒total and convergent validity correlations between the RSES-7 and SRHQ

Color gradient represents correlation level. Pink represents a positive correlation. Purple represents a negative correlation

Abbreviations: Pos positive subscale, Neg negative subscale, RSES Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Self-Phy Self-Rated Physical Condition, Self-Psy Self-Rated Psychological Condition, SRHQ Self-Rated Health Questionnaire, T1 baseline, T2 1-week follow-up, T3 15-week follow-up

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω were used to evaluate the internal consistency of the subscales and the total scores of the most recommended form—the RSES-7 for the three waves (see Table 5). The results showed that the RSES-7 had excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.905‒0.937; McDonald’s ω = 0.904‒0.936), as well as the RSES-10 (Cronbach’s α = 0.911‒0.942; McDonald’s ω = 0.915‒0.944; see Supplementary Material, Table S5, for more details).

Test–retest reliability

The test–retest reliability of the RSES-7 is reported in Table 5. The overall scale and the positive subscale showed adequate results, but not the negative subscale (ICC = 0.579‒0.717). The RSES-10 also displayed similar results (ICC = 0.642‒0.790), with low test–retest reliability for the negative schedule (see Supplementary Material, Table S5, for more details).

Discussion

This paper presents a validation of the Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), using a three-wave assessment to examine its main psychometric properties and measurement invariances. The findings add another piece of robust evidence to support the ongoing psychometric evaluation of the RSES. Given the current context in China and the results of the tests conducted, the RSES-7, which is a modified version of the RSES that excludes Items 5, 8, and 9, has been identified as a potentially more suitable measure for self-esteem. In this study, this brief version, which incorporated simplified Chinese language, demonstrated robust reliability, validity, and measurement invariance.

Converging evidence demonstrates that response artifacts (e.g., social desirability) may occur when all questions are stated in one direction, and leads to questionable test results [59]. To partially mitigate the potentially invalidating effects of acquiescence, the RSES was designed to consist of five positively worded and five negatively worded items [59]. However, including positive and negative wording to examine the same dimension might lead to response bias, so threatening validity; this is a phenomenon known as the wording effect [60, 61]. Given the specificity of the different cohorts used to examine the properties of the RSES and the inherent differences between Eastern and Western cultures, even when the factor structure is known, it is necessary to perform EFA on the data from different cohorts to further examine the factor loadings and cross-loading phenomena, and identify potential and fundamental issues with the items. Items 5, 8, and 9, all of whichare negatively worded, exhibited inapplicability, and the reason for this was worth exploring. Cross-cultural differences have, therefore, been observed in Chinese versions of the RSES, and a similar situation has been identified in other language versions [21, 22, 24, 62]. A multi-center cross-cultural study involving nearly 17 000 participants from 53 countries found that participants responded truthfully to positively worded items, while showing significant concealment for negatively worded items [9]. This indicates that people from many cultures tend to be biased toward negatively worded items. Additionally, a study across three countries showed that some respondent experience difficulty answering the negatively-worded questions effectively, resulting in serious consequences (e.g., low scale reliability) [63].

The reasons for the inconsistent factor structure regarding Items 5, 8, and 9 are worth exploring. Self-esteem is rooted in Western culture and expresses a greater emphasis on the self as a valuded, independent individual. In China, although there has been a tremendous increase in people’s literacy and self-awareness, humility and altruism are still significant values in Chinese culture. In Eastern cultures, people are more inclined to situate the self in interactions with others, which is an inevitable cultural difference compared to in the West [64]. From an early age, Chinese children are often taught to be humble and that pride makes people fall behind. This may lead to the inconsistent dimensional attribution of Item 5 of the RSES [65]. Sixty-eight percent of the impact of social media use on mental health is mediated by self-esteem [66], and in the Internet era, contacting successful people worldwide has become easier. Over time, this may elicit a sense of falling behind. For example, respondents to the RSES who major in medicine may be exceptional, hard-working, and self-demanding individuals [67], but they might still perceive themselves as a failure compared to their peers, leading to inconsistent dimensional attributions for Item 9. Whether to remove Item 8 has been of long-standing debate among scholars [68]. The discrepant understanding of the word “wish” in different cultural contexts and ideas about modesty in Chinese culture have led to the phenomenon whereby people with high self-esteem may also hope for continued respect [65]. Due to the inevitable cultural differences, to date, there has been no particularly effective solution for Item 8 [69]. However, the present study, which was based on a three-wave design, offers strong evidence for the deletion of Item 8.

Scale maladaptation in cross-cultural applications is the norm. Furthermore, Chinese people are often characterized by dialecticism [70]. This is reflected in a scale that tends to support both sides of the issue, that is, both positive and negative expressions of self-esteem. A cross-cultural study between China and US showed that four of the five negatively-worded items were answered differently by respondents from the two countries [71]. Some cross-cultural studies exclude negatively worded items when using the RSES [62], which is the reason why we explored five models.

Overall, the present study, which utilized a substantial sample across three waves, yielded consistent results that provide compelling evidence for cross-cultural differences regarding Items 5, 8, and 9. When the oblique rotation was applied, the pattern load, which is essentially a regression coefficient, exceeded 1. Consequently, the RSES-7 was considered to be the best model even when the factor loading for Item 6 was greater than 1. Although less information is inevitably collected when items are deleted, when we removed items from the negatively-worded dimension, we retained the two-factor structure. Generally, the RSES-7 is an easy-to-use instrument with strong validity data for self-esteem measurement.

Self-esteem varies widely across groups, and a large study based on a sample of nearly one million participants found an age-related increase in self-esteem from late adolescence to mid-adulthood, and that self-esteem was significantly higher in men than in women [47]. Group comparisons and longitudinal changes are fundamental to understanding the role of self-esteem in psychological well-being. Therefore, it is important to examine whether the measurement properties of the RSES are comparable across groups (CMI) and stable across time (LMI). However, few studies have tested these forms of measurement invariance for the RSES. With our CMI evidence, we found that subgroups of students who participate in sports, have higher family incomes, and are involved in part-time jobs, have higher self-esteem [72]. With all eight subgroups, the RSES-7 achieved strict invariance across the three waves, which means that differences in self-esteem itself are well-identified when comparing these subgroups.

Based on a three-wave design, the RSES-7 achieved the strict invariance models in longitudinal CFA, indicating that the residual invariance constrains factor loadings, item intercepts, and residual variances, and does not change across time points. This implies that if the scores had changed over time, this would have been caused by a change in the latent variable and not by a change in item understanding. The present study adds LMI across 15 weeks to the psychometric evidence for the RSES; the LMI provided robust evidence regarding the assessed construct and had the same meaning across time points, which will support the design of for future longitudinal studies.

Recommendations

The RSES-10 has a suboptimal factor structure, validity, and measurement invariance, yet it is advantageous for cross-cultural comparisons; the RSES-7 is the simplest and most robust form of the RSES and has adequate psychometric properties and measurement invariance; therefore, we recommend the RSES-7 as the preferred solution for use with Chinese university students.

Strengths and weaknesses

This paper presents a large-scale validation of the Chinese Macau adaptation of the RSES in the Chinese mainland. After a dramatic change in the Chinese socio-cultural context, the study re-evaluated the psychometric properties of the previously translated traditional language version of the RSES by utilizing the simplified Chinese language. Ultimately, a more concise and potentially applicable form of the RSES—a 7-item form—was proposed. Second, by retaining the two original factors with a reduced number of items, the RSES-7 has the potential to alleviate the response burden on respondents. Third, although the RSES has been validated worldwide, the longitudinal design used here (baseline, 1-week follow-up, 15-week follow-up), with a large sample size, was a particular advantage and provided robust evidence. Lastly, a comprehensive and systematic assessment of the psychometric properties based on COSMIN and STROBE guidelines, in which CMI was evaluated for a wide range of socio-demographic variables and LMI was estimated for the three-wave measure, was unprecedented.

Nonetheless, some limitations of our study need to be considered. The respondents were drawn from one university, representing a specific group of Chinese millennials in the medical specialty. The homogeneity of the population was taken to provide a more accurate historical and social focus but it limits the generalizability of the findings to the same age groups. In the same vein, the present study tested the RSES-7 in the Chinese mainland context and hence, its usability in other cultural contexts remains to be explored. Third, although item removal was accomplished while retaining a two-factor structure, reduced information resulting from the use of fewer items is inevitable. Finally, although it is noteworthy that we used the original 10-item RSES to retrieve the data from which the seven item selected RSES-7 were identified, the findings of participants’ responses may still have been confounded by removing three items. As a result, the psychometric qualities of the RSES-7 require further examination.

Future directions

Further investigation is warranted through a comprehensive survey of healthcare students from diverse regions and specialties to determine if the aforementioned findings can be replicated. In addition, as a more concise version, the RSES-7 requires comparative analysis with other self-esteem scales to further assess its psychometric properties. In response to the item deletions, while we tentatively conclude that they were not due to methodological effects, the underlying linguistic reasons need to be further explored. Lastly, the RSES is available in many languages, but large-scale cross-cultural measurement invariance has not been evaluated. In the future, we hope to join forces with researchers from other countries and regions to further explore the cross-cultural invariance of the RSES.

Conclusion

This study revealed that Items 5, 8, and 9 of the RSES pose potential risks to its structural stability and may hinder cross-cultural comparability. These findings enhance our understanding of the RSES. Cross-sectional measurement invariance across eight subgroups, and longitudinal measurement invariance based on three-wave assessments, were well demonstrated, providing support for the psychometric qualities of the RSES-7. This enlightens future studies to validate the RSES-7 in different regions and populations. If its psychometric properties remain adequate, this simplified form of the RSES would facilitate a lower response burden, more efficient analysis, and wider application.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the ethics committee. The dataset supporting the conclusions is available upon reasonable request to the last author.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

comparative fit index

- CMI:

-

cross-sectional measurement invariance

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments

- EFA:

-

exploratory factor analysis

- ICC:

-

intraclass correlation coefficient

- KMO:

-

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

- LMI:

-

longitudinal measurement invariance

- RMSEA:

-

root mean square error of approximation

- RSES:

-

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

- SRHQ:

-

Self-Rated Health Questionnaire

- SRMR:

-

standardized root mean residual

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis index

- WLSMV:

-

weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted

References

Rosenberg M: Society and the Adolescent Self-Image: Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400876136

O’Donnell K, Brydon L, Wright CE, Steptoe A. Self-esteem levels and cardiovascular and inflammatory responses to acute stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(8):1241–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.012.

Rodriguez-Solana A, Gracia-Marco L, Llorente-Cantarero FJ, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Marmol-Perez A, Gil-Cosano JJ, Moliner-Urdiales D, Ubago-Guisado E. Is higher physical fitness associated with better psychological health in young pediatric cancer survivors? A cross-sectional study from the iBoneFIT project. Scand J Med Sci Spor. 2023;33(7):1157–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14345

MacDonald G, Saltzman JL, Leary MR. Social approval and trait self-esteem. J Res Pers. 2003;37(2):23–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00531-7.

Roberts SB, Kendler KS. Neuroticism and self-esteem as indices of the vulnerability to major depression in women. Psychol Med. 1999;29(5):1101–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799008739.

Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Does cosmetic outcome from treatment of primary breast cancer influence psychosocial morbidity? Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25(6):571–3. https://doi.org/10.1053/ejso.1999.0708.

Button E, Reveley C, Palmer R. An ethnic comparison of eating attitudes and associated psychological problems in young British women. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(3):317–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199804)23:3%3c317::AID-EAT9%3e3.0.CO;2-M.

Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Pederson Mussell M, Crow SJ, Miller JP. Binge eating disorder with and without a history of purging symptoms. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;24(3):251–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199811)24:3%3c251::AID-EAT2%3e3.0.CO;2-L.

Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous Administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 Nations: Exploring the Universal and Culture-Specific Features of Global Self-Esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(4):623–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623.

Rosenberg M: Conceiving the Self: New York: Basic Books; 1979. https://doi.org/10.2307/3340091

Roth M, Altmann T. A Comparison of the Predictive Validity of Self-Esteem Level and Directly Measured Self-Esteem Stability in the Temporal Prediction of Psychological Distress. Front Psychol. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01770

Heatherton TF, Polivy J. Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(6):895–910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.895.

Vallieres EF, Vallerand RJ. Traduction et Validation Canadienne-Française de L’échelle de L’estime de Soi de Rosenberg. Int J Psychol. 1990;25(2):305–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599008247865.

Prezza M, Trombaccia FR, Armento L: La scala dell'autostima di Rosenberg: Traduzione e validazione Italiana. [The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Italian translation and validation.]. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali 1997, 223:35-44.

Kourakou A, Tigani X, Bacopoulou F, Vlachakis D, Papakonstantinou E, Simidala S, Ktena E, Katsaouni S, Chrousos G, Darviri C. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and Validation in the Greek Language in Adolescents. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1339:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78787-5_13.

Piyavhatkul N, Aroonpongpaisal S, Patjanasoontorn N, Rongbutsri S, Maneeganondh S, Pimpanit W. Validity and reliability of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale-Thai version as compared to the Self-Esteem Visual Analog Scale. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94(7):857–62.

Franck E, De Raedt R, Barbez C, Rosseel Y. Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Psychologica Belgica. 2008;48(1):25–35. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-48-1-25.

Mimura C, Griffiths P. A Japanese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: translation and equivalence assessment. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(5):589–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.11.004.

García-Batista ZE, Guerra-Peña K, Garrido LE, Cantisano-Guzmán LM, Moretti L, Cano-Vindel A, Arias VB, Medrano LA. Using Constrained Factor Mixture Analysis to Validate Mixed-Worded Psychological Scales: The Case of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in the Dominican Republic. Front Psychol. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636693

Mayordomo T, Gutierrez M, Sales A. Adapting and validating the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale for elderly Spanish population. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(2):183–90. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636693.

Makhubela M, Mashegoane S. Psychological validation of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) in South Africa: Method effects and dimensionality in black African and white university students. J Psychol Afr. 2017;27(3):277–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219001170.

Cong CW, Cheong JY. Validation of Rosenberg self-esteem scale for Malaysian adolescents. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(21):17835–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02960-z.

Gnambs T, Scharl A, Schroeders U. The structure of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: A cross-cultural meta-analysis. Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 2018;226:14–29. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000317.

Yifu Ji XY. The Self-Esteem Scale, SES (in Chinese). Chin J Ment Health. 1993;251–2.

Cheng S-T, Hamid PN. An Error in the Use of Translated Scales: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale for Chinese. Percept Mot Skills. 1995;81(2):431–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/003151259508100214.

Shek DTL. Please Don’t Drop an Item So Quickly: A Comment on Cheng and Hamid’s Syntax Incompatibility Error. Percept Mot Skills. 1995;81(3):977–8. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.81.3.977.

Hamid PN, Cheng S-T. To Drop or Not to Drop an Ambiguous Item: A Reply to Shek. Percept Mot Skills. 1995;81(3):988–90. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.81.3.988.

Tsang S. Parenting and Self-Esteem of Senior Primary School Students in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Boys & Girls’ Club Association of Hong Kong; 1997.

Chenan Liang PW. Validity and reliability of Chinese Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (in Chinese). New Horizons in Education. 2008;56(1):62–9.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

Mundfrom DJ, Shaw DG, Ke T-L. Minimum Sample Size Recommendations for Conducting Factor Analyses. Int J Test. 2005;5(2):159–68. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0502_4.

Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J: Health Measurement Scales: A practical guide to their development and use. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL. Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12(4):142s–58s. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-2456(05)80019-4.

Zhu Y, Jiang C, Yang Y, Dzierzewski JM, Spruyt K, Zhang B, Huang M, Ge H, Rong Y, Ola BA, et al. Depression and Anxiety Mediate the Association between Sleep Quality and Self-Rated Health in Healthcare Students. Behav Sci. 2023;13(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020082.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006.

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, Terwee CB. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1147–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3.

Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th ed. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2016.

Korkmaz S, Goksuluk D, Zararsiz G. MVN: An R package for assessing multivariate normality. The R Journal. 2014;6(2):151–62. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2014-031.

Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

Polit DF: Measurement and the Measurement of Change: A Primer for the Health Professions: Wolters Kluwer Philadelphia; 2016.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007.

Comrey LA, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Psychology Press; 1992.

Li C-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. 2016;48(3):936–49. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7.

Joseph F. Hair WCB, Barry J. Babin, Rolph E. Anderson: Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition, 7th ed.: London: Pearson Higher Education; 2014.

Mulaik SA, James LR, Van Alstine J, Bennett N, Lind S, Stilwell CD. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(3):430–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.430.

Jorgensen TD, Pornprasertmanit, S., Schoemann, A. M., Rosseel, Y: semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling. 2020.

Bleidorn W, Arslan RC, Denissen JJA, Rentfrow PJ, Gebauer JE, Potter J, Gosling SD. Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;111(3):396–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000078.

Meade AW, Johnson EC, Braddy PW. Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(3):568–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568.

Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(3):464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834.

Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Struct Equ Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–55. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5.

Fornell C, Larcker DF: Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. US: American Marketing Association; 1981;18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312.

Peters GY GS: ufs: A collection of utilities. Published 2021. Accessed.

Cho E, Kim S. Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha: Well Known but Poorly Understood. Organ Res Methods. 2015;18(2):207–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114555994.

Revelle W, Condon DM. Reliability from α to ω: A tutorial. Psychol Assess. 2019;31(12):1395–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000754.

Kline P. The Handbook of Psychological Testing. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1993. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315812274.

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012.

Gamer M LJ, Singh I: irr: Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. https://rdrr.io/cran/irr/ Web site. Accessed.

Nelemans SA, Meeus WHJ, Branje SJT, Van Leeuwen K, Colpin H, Verschueren K, Goossens L. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) Short Form: Longitudinal Measurement Invariance in Two Community Samples of Youth. Assessment. 2017;26(2):235–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116685808.

Hinz A, Michalski D, Schwarz R, Herzberg PY. The acquiescence effect in responding to a questionnaire. Psychosc Med. 2007;4:Doc07.

Nieto MD, Garrido LE, Martínez-Molina A, Abad FJ. Modeling Wording Effects Does Not Help in Recovering Uncontaminated Person Scores: A Systematic Evaluation With Random Intercept Item Factor Analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685326.

DiStefano C, Motl RW. Further Investigating Method Effects Associated With Negatively Worded Items on Self-Report Surveys. Struct Equ Model. 2006;13(3):440–64. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1303_6.

Bean RA, Bush KR, McKenry PC, Wilson SM. The Impact of Parental Support, Behavioral Control, and Psychological Control on the Academic Achievement and Self-Esteem of African American and European American Adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2003;18(5):523–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558403255070.

Steinmann I, Strietholt R, Braeken J. A constrained factor mixture analysis model for consistent and inconsistent respondents to mixed-worded scales. Psychol Methods. 2022;27(4):667–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000392.

Baranik LE, Meade AW, Lakey CE, Lance CE, Hu C, Hua W, Michalos A. Examining the Differential Item Functioning of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Across Eight Countries1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2008;38(7):1867–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00372.x.

Wu CH. An examination of the wording effect in the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale among culturally Chinese people. J Soc Psychol. 2008;148(5):535–51. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.148.5.535-552.

Plackett R, Sheringham J, Dykxhoorn J. The longitudinal effect of social media use on adolescent mental health in the UK: findings from the UK Longitudinal Household Study. Lancet. 2022;400:S71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02281-4.

Latas M, Stojković T, Ralić T, Jovanović S, Spirić Z, Milovanović S. Medical students’ health-related quality of life–a comparative study. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2014;71(8):751–6. https://doi.org/10.2298/vsp1408751l.

Xu M, Leung S-O. Bifactor Structure for the Categorical Chinese Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Span J Psychol. 2016;19:E67. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.66.

Leung SO. WPM: A study on reliability and validity of Chinese Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (in Chinese). New Horizons in Education. 2008;56:62–9.

Peng K, Nisbett RE. Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. Am Psychol. 1999;54:741–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2016.66.

Song H, Cai H, Brown JD, Grimm KJ. Differential item functioning of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in the US and China: Measurement bias matters. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2011;14(3):176–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2011.01347.x.

Ozsaker M, Dorak F, Vurgun N. Self esteem, physical activity and sedentary lifestyle associated with physical performance among Turkish elemantary school children. HealthMED. 2012;6(5):1636–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank two peer reviewers and the Editor for their excellent opinions and suggestions. The authors also thank all the study participants and research assistants for their contributions.

Funding

This study was supported by the Medical Research Fund of Zhejiang Province, Grant No. 2023RC073 and the Research Initiation Fund of Hangzhou Normal University, Grant No. RWSK20201003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJ, YZ, and YL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. C-S T, SM, PC, LC, and LG: Methodology, Validation, Writing—Review and Editing. HM: Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation. RM: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hangzhou Normal University Division of Health Sciences, China (Reference No. 20190076), thus ensuring that it adhered to the standards set by the Helsinki Declaration. All healthcare students freely consented to completing the questionnaires and provided their informed consent before they were included in the survey. The authors confirmed full respect and protection of individual privacy rights before, during and after the data collection and processing.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Spearman inter‒factor, factor‒total, and convergent validity correlations between the RSES-10 and SRHQ. Table S1. Characteristics of participants (N = 481). Table S2. EFA factor loadings: RSES-9, RSES-8, RSES-6, and RSES-5. Table S3. Cross-sectional measurement invariances: RSES-10 with two factors. Table S4. The average variance extracted and construct reliability of the RSES-7 in convergent validity. Table S5. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability: RSES-10 and SRHQ.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, C., Zhu, Y., Luo, Y. et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: evidence from a three-wave longitudinal study. BMC Psychol 11, 345 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01293-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01293-1