Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are remitting and relapsing diseases that mainly interest the gastrointestinal tract. IBD is associated with a condition of psycho-social discomfort that deeply compromises the quality of life and the competence of patient to be fully engaged in their self-management. As a consequence, effective care of IBD patients should include not only medical but also psychological support in order to improve patients' wellbeing. Although this, to date there is no standardized approach to promote psychological wellbeing of IBD patients in order to improve the perception of the quality of the care. To fill this gap, a consensus conference has been organized in order to define the psychosocial needs of IBD patients and to promote their engagement in daily clinical practice. This paper describes the process implemented and illustrates the recommendations deriving from it, which focus on the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in IBD management.

Results

The consensus conference has been organized in three phases: (1) literature review about life experiences, engagement, and psychosocial needs of IBD patients; (2) workshops with IBD experts and patients’ representatives; (3) drafting of statements and voting. Seventy-three participants were involved in the consensus conference, and sixteen statements have been voted and approved during the consensus process.

Conclusions

The main conclusion is the necessity of the early detection of – and, in case of need, intervention on- psycho-social needs of patients in order to achieve patient involvement in IBD care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are remitting and relapsing conditions that mainly interest the gastrointestinal tract. IBD include two heterogeneous diseases, ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) [1]. It is estimated that in Italy about 200,000 people are affected by IBD [2]. CD and UC can occur in every age of life but the highest incidence is documented between 20 and 40 years [3]. IBD are chronic diseases requiring multiple interventions and continuous monitoring and adaptation processes by patients and family members [2]. This is associated with a condition of psycho-social sufferance that prevents the affected person from living normally and deeply compromises the quality of life in terms of personal, work, and interpersonal well-being [2]. Management of IBD patients should include not only purely medical but also psychosocial aspects in order to improve patients' wellbeing and quality of life [4] and their ability to get fully engaged in self-management [5]. A growing corpus of literature has indeed demonstrated that promoting patients’ active engagement in their care process has proven to be an effective strategy to achieve a better patient's quality of life in various chronic care contexts (e.g. diabetes, kidney disease) [6] and in different phases of life (e.g. childhood or adolescence) [7]. The word “patient engagement” embodies several related concepts, including patient-centered care and shared decision-making, all of which are built on the principle of involving patients as full partners in their healthcare path [8]. Patient engagement, indeed, aims at giving a protagonist role to patients for a more efficient and effective process of care delivery. There in a lot of evidence in the literature that patient engagement is linked with a better patient self-management, a decreased use of healthcare and fewer adverse events [9]. Particularly, scientific studies have demonstrated that patients who are more engaged in their care reports better medical results [10], higher quality of life [11], higher satisfaction with their care relationship, healthier behaviors [12], more effective self-management skills [13] and treatment adherence [13]. Furthermore, some research has shown that patient engagement may contribute to a reduction of healthcare costs and to economically more sustainable organizational processes [14]. Previous research has proven that emotional adjustment and psychological wellbeing is a crucial antecedent of positive patient engagement and participation in his/ her health care process management; so is crucial to grant psychological support in order to have a more involved patient [15]. Although the undoubted role of patient engagement in the decision-making process, to date there is no standardized approach to promote the engagement and little attention is paid to social and psychological needs of subjects with IBD [16].

To fill this gap, A.M.I.C.I. association (the Italian association of IBD patients), the Higher Institute of Health and EngageMindsHUB – Consumer, Food & Health Engagement Research Center of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore organized a consensus conference (see Materials and methods) involving gastroenterologists, healthcare professionals expert in IBD care and IBD patients in order to define the priorities and best practices of care to ensure a self-management of the psychosocial needs of IBD patients which may improve their quality of life and engagement self-management. Here, we report the literature evidence and practical recommendations that emerged from the consensus process.

Materials and methods

The consensus conference was conducted in accordance with the Consensus Development Program of the United States’ National Institutes of Health [17] (all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations) and was aimed to draft recommendations to answer the following three questions a priori determined by the project coordinators:

-

1.

What are suggested strategies to ensure the management of psycho-social needs of pediatric IBD patients in order to improve their patient engagement?

-

2.

What are suggested strategies to ensure the management of psycho-social needs of adult IBD patients in order to improve their patient engagement?

-

3.

What e-health technologies are available for improving IBD patients’ psychological wellbeing and engagement?

The consensus conference was divided into three steps: (1) literature review on published evidence about life experiences, engagement, and psychosocial needs of IBD patients (see Appendix 2 for literature review details and Volpato et. Al. [18]); (2) workshops with IBD experts and patients representatives (held in October 2019); (3) drafting of statements and voting. The final drafting and presentation to the press was held on the 23rd and 24th of June 2020.

Participants

A purposive selection of participants was made by following two steps: (1) identification of the categories of stakeholders/actors relevant to IBD management (see Table 2); (2) identification and enrollment—for each category—of prototypical representatives (bearers of experience in the field and/or opinion leaders in the context of reference). Due to the goal of ensuring multi-disciplinarity in the selection of experts, no fixed criteria were a priori settled to define the extent of expertise and we followed a broad inclusive concept of expertise such as the ownership of the relevant knowledge, skills and experience in the management of IBD care. Furthermore, experts have been defined as relevant key opinion leaders in their field of scientific expertise. In order to guarantee the scientific standards of the process the stakeholders involved in the project were asked to sign a conflict-of-interest statement and to accept the Consensus conference regulation. The Research Team paid close attention to guarantee the equal chance for everyone to express his/her own opinion in the workshops and meetings to discuss the collected evidence. Furthermore, according to the methodology of Consensus Conference approach, an organizational structure for the Consensus Process was set up as described in Table 1 [19]. A detailed list of participants in the different roles is provided in the Appendix 1.

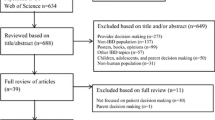

Literature review

A systematic search of the scientific literature was conducted in electronic databases from January 2009 to October 2019 in accordance with the approach defined by Arksey and O’Malley [20] and the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews [21]. A detailed description of the literature review process is provided in the Appendix 2 [18].

Workshops

Five workshops were organized. One workshop addressed the technology question, while the questions about needs and interventions were each articulated in two workshops (one focused on the developmental age and one on the adult age). All workshops involved a balanced mix of IBD experts and patients’ representatives following the maximum variety coverage criterion [17]. The workshops – moderated in a non-directive approach [22]–had a scheduled duration of 4 h. The moderators ensured the equal participation of patients and caregivers advocates in all the meetings. The documents generated during the workshops were discussed, revised, and enriched by the Panel of Jury participants in order to reach a collegial approval.

Consensus statements

Finally, the jury panel (to see the composition of the jury panel see Appendix 1) revised the workshop reports in order to elaborate the final statements of the consensus. The jury panel, discussed, drafted, voted and approved the final document. The statements included in the document were selected on the basis of a twofold criterion of (1) being approved by the majority of the panel members; (2) having received no overt expression of dissent.

Results

Seventy-three participants were involved in the consensus conference including IBD experts from different scientific and professional fields and representatives of patient associations (Table 2).

The available literature evidence on this topic has also been previously reported more broadly by Volpato and colleagues [18].

Main strategies to ensure the management of psycho-social needs of pediatric IBD patients in order to improve their patient engagement

Literature evidence

Psychosocial needs of pediatric patients with IBD include three main topics: transmission of information/knowledge, psychological/psychotherapeutic interventions, and promotion of psychosocial support [23].

An adequate communication of disease-related information to the patient (literacy) is associated with a better disease management with possible positive effects on coping competencies, perception of self-efficacy, and satisfaction with the services received [23, 24]. On this point, there are problems of continuity in the flow of information related to organizational dysfunctionality [25], especially in the moment of transition between medical structures dedicated to pediatric and to adult age.

Pediatric IBD patients experience a higher rate of psychological problems (e.g. depression, sense of helplessness, anxiety, family problems, and school difficulties) compared with the general population, requiring more psychological support [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Several validated psycho-diagnostic tools are available for the management of IBD, including the Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) Family Impact Module [32], the KidScreen-10 [33], the IBD Specific Anxiety Scale (IBD-SAS) [34], and the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [35]). Interestingly, most psychotherapeutic treatments showed to be effective in terms of clinical management of disease and psychological support to the patient [36,37,38,39].

Finally, attention should be paid to the psychosocial support to the pediatric IBD patient [40]. This could be done in various methods such as narrative exchange of experiences, self-help groups, mapping strengths and weaknesses of patients and their network of social support, development of coping and problem-solving skills, integration of peers/family contexts/care settings [41]. In this, patient associations can play a big role [42]. The transition in the management of IBD from childhood to adulthood should also be considered, supporting the integration between these phases both in terms of patient's personal identity and health organization and coordination of the operators involved [43, 44]. Importantly, the cooperation between physicians and nurses in this transition period is crucial to ensure an optimal management [45,46,47]. In addition, the connection between health care professionals and school/life contexts has been associated with improved patient care [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Of note, an uncomfortable social context could lead – not only to a worse physical symptoms management (tiredness, use of bathrooms…)- but also to negative behaviors such as personal isolation, feelings of embarrassment/humiliation in relationships, and difficulty in formulating requests for help [55,56,57]. The role of family and caregivers is relevant in the management of IBD patients during childhood, but to date it is still poorly explored [58]. On the other hand, appreciable results on caregivers’ quality of life and disease management capabilities were reported after psychological and social support interventions [59, 60]. The coordination between different professional figures (e.g. health professional, psychologist, nutritionist, and social worker) could improve the synergy in responding to specific psycho-social needs of patients (in addition to the clinical ones) and support patient engagement in the care process [61,62,63,64].

Final consensus statement

Based on literature evidence, attention should be given to the psychological needs of pediatric IBD patients in order to ensure their full engagement in care management and to improve their quality-of-care experience. In this scope, the experts claimed for the following recommendations.

IBD patients should be managed through a multidisciplinary approach

Different professionals should be involved in the management of pediatric IBD patients including physicians (gastroenterologists, radiologists, surgeons, pediatricians, rheumatologists, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and general practitioners), nurses, psychologists, nutritionists, and social workers [65, 66]. This in order to take care not only of the medical needs of the patients but also of the psychosocial ones [67].

Patients with IBD should be provided with early psychological screening and psychosocial support

Patient psychology should be investigated already at the time of IBD diagnosis to promptly identify patients at risk of psychological and social distress [68]. The assessment should consider the social and psychological status of the patient in order to intervene on a targeted psychotherapeutic plan and/or on a psychosocial plan to promote adaptation and self-management, as well as to build a proactive role (engagement) in the management of disease impacting on quality of life. Patient's distress should be evaluated at each follow-up visit and/or hospital access: in case of critical psychosocial status an intervention has to be planned [69].

Psychosocial support should be provided to IBD patient's family/caregiver

Even if it is often reported in the clinical settings, there is still little scientific evidence about the distress of family and caregivers of IBD patients [61]. More studies are needed to deepen and to improve the interventions dedicated to them, as well as to define their role in the management of pediatric IBD patients.

Connection/cooperation between IBD patient’s clinical structure and school should be guaranteed

It is necessary to provide n adequate information on IBD at school and to promote collaboration between health caregivers and teaching staff to guarantee better physical symptoms management (tiredness, diarrhea…) prevent disease-related stigma and the loss of educational continuity during relapses or hospitalizations.

Awareness about IBD in evolutive age should be increased in the general population

Greater awareness in the general population about IBD during childhood and adolescence is necessary to limit the formation of social stigma and contain its negative effects on patients’ life [70]. A recent survey conducted by the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) found that patient organizations play a key role in reducing fears and worries of IBD patients [42] For this reason, close cooperation between physicians and patient associations is desirable in order to promote activities of dissemination of information about IBD and to ensure an optimal management of this chronic condition.

IBD patient’s transitioning from pediatrics to adulthood should be managed through the combined work of pediatric and adult experts (transitional ambulatory)

Pediatric and adult professionals should be involved in the management of patients with intermediate age to guide therapeutic decisions [71].

Main strategies to ensure the management of psycho-social needs of adult IBD patients in order to improve their patient engagement

Main evidence

A higher proportion of psychological distress (e.g. anxiety and depression) is detected in adult IBD patients than in both general population and patients with other diseases [72, 73]. IBD patients may have an altered perception of their body image, resulting in a negative impact on subjective well-being [74, 75]. In addition, IBD-related fatigue is associated with a decreased quality of life [76]. Regarding human relationships, adult IBD patients tend to social withdrawal and to experience considerable difficulties in adapting to daily and working life due to the unpredictability of the disease course [77, 78].

Several psychotherapeutic and psychosocial interventions are available to achieve adequate levels of well-being and quality of life. In this context, different initiatives have been proposed including a focus on diet, physical activity, sleep [79,80,81,82,83], and restoration of a good social relationship [81, 82, 84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Effective clinical and social management of IBD requires the active involvement of health care stakeholders and health care organizations implicated in this condition [94, 95].

To date, there is a gap between the level of information on disease provided by health professionals and the one required by patients [96,97,98]. An appropriate transmission of information is a prerequisite for the development of patient engagement [99]. Interestingly, engagement programs should involve not only the patient but also the family, caregivers, and the care team [94, 95].

With regard to the care team, programs have been developed to improve communication skills strengthening the physician–patient relationship [49, 96, 100]. Similarly to what found for pediatric patients, the psycho-social needs should be taken into account in a multidisciplinary perspective also in adult IBD patients in order to integrate the performances of health professionals (doctors, nurses…) and lay people (family members, caregivers, and patients' associations) [101]. Consequently, the involvement of non-medical personnel in the management of IBD patients and caregivers should be enhanced [86,87,88,89, 102]. Growing evidence shows that the physician should be accompanied by a figure (case manager) who coordinates the interactions among IBD patient, hospital, and any other parties [103]. This multidisciplinary strategy should be associated with organizational changes leading to the development of IBD unit including physicians, nurses, and psychologists to meet patients’ needs [101, 104] and ensure continuity of care [105].

Final consensus statement

Based on the indications offered by the literature, the experts formulated seven recommendations for the management of IBD patients.

An integrated approach to the adult IBD patient should be used

A multidisciplinary structured approach is needed to take care (in addition of the medical ones) of psycho-socio-assistential-existential needs of IBD patients. Dedicated and specialized nurses and psychologists should be fully integrated in IBD management unit (composed by all the members that, at various levels, address IBD).

Active IBD patient engagement should be promoted

Effective response to patient's psychosocial needs (in addition of the clinical ones) requires the engagement of patients, family members/caregivers, and care providers through appropriate information and support interventions.

IBD physician–patient communication should be enhanced

Specific attention should be paid to physician–patient communication through communication and empathy training programs to improve the effectiveness of the therapeutic relationship. Communication should be flexibly modulated in relation to critical moments and specific phases of the patient journey (diagnosis, pre and post-surgical phases, worsening of the condition…).

Continuity of IBD care should be monitored

It is necessary to ensure a therapeutic continuity to achieve an effective response (in addition of the clinical ones) to the psycho-social needs of patients.

Adult IBD patient support should be planned

For the adult patient, psychological (and, if necessary, psychotherapeutic) support should be planned and implemented, to overcome critical moments and achieve/maintain good levels of quality of life.

IBD patients’ family and caregiver support should be planned

More attention should be paid to family members and caregivers implementing psychological/psychosocial initiatives dedicated to them [106].

General knowledge about IBD should be improved

Communication interventions should be implemented and maintained in order to improve knowledge of IBD, its psycho-social impact on quality of life, and reduce the negative effects of social stigma related to IBD [107].

What e-health technologies are available for improving IBD patients psychological wellbeing and engagement?

Main evidence

E-Health is a wide term, and is referred to the utilization of information and communications technologies in the healthcare world [108]. Scientific research, although in its beginnings, has already highlighted some opportunities for the application of e-health technologies in the management of chronic diseases, such IBD. Among the most important: the possibility of sharing stories and experiences to support the emotional management of one's pathology [109]; the supply of an effective support to maintain therapeutic continuity and promote the physician–patient relationship even in "remote" settings [110]. E-health technologies can also limit the spread of fake news (linked to the use of unreliable or inaccurate digital sources to search for information on a pathology) by spreading correct information [111].

Moreover, several e-health tools are available to be used in different fields and patient groups in chronic care management [111, 112]. Web-apps can provide the adult patient with useful information for self-education, monitoring of disease and side effects, as well as for therapeutic decision-making [106, 110, 113]. Telemedicine can be an effective communication channel between patient and physician outside the routine clinical practice (e.g.: unexpected events, need for unscheduled consultations in the presence of unpredictable flare-ups) [110]; more in particular, in young and adolescent patients, a telemedicine-based approach can be useful to support the achievement of skills and competencies (self-management, adherence, therapeutic relationship satisfaction…) in the transition to adulthood, saving time, costs and ensuring disease monitoring [114]. Social media can play an elective role in sharing experiences and promoting social support [114]. Finally, groups and disease-related web pages represent an important "place" for the creation of a lay network of sharing and support, in particular when physical participation is not possible or complicated [115].

Consensus statement

Based on the available evidence, three statements were approved with reference to new technologies.

Further studies on usability and effectiveness of e-health technologies in IBD management should be promoted

The use of e-health technologies, even if the first pieces of evidence are encouraging, requires further research with respect to usability and effectiveness.

Personalized e-health interventions in IBD management should be planned according to the characteristics of the target audience

The e-health technologies should be chosen on the basis of available tools, patient targets, and combination between target and tool specificity (e.g.: a too sophisticated technology for an old or a low-cultured patient could not work being too difficult for him to use).

E-health interventions in IBD management should be planned according to the demonstrated utility

The choice of specific e-health technologies should be justified by its proven usefulness (e.g. sharing of experiences among patients, therapeutic continuity, and prevention of fake news).

The statements at a glance

The whole of the statements of this consensus conference is also summarized in the Table 3.

Discussion

IBD disease has an undoubted impact on patients’ quality of life with important consequences at psychosocial level [116]. However, psychosocial support for IBD care is still underestimated and there is no clear consensus on priorities for interventions. In addition, although patient engagement is a crucial target in chronic care, it often appears to be an abstract principle and it is not applied to clinical practice117. Based on these considerations, we conducted a consensus conference to animate a scientific, multidisciplinary, and inclusive debate in which IBD patients could participate together with scientists and healthcare professional with the final aim of improving psycho-social wellbeing and engagement of IBD patients. This project was the occasion to bridge expertise, visions, and concerns from multiples scientific disciplines and with the subjective and crucial expertise of the patients about their needs and priorities. So, a co-constructive and collaborative endeavor was enabled along the whole consensus process and this in itself constitutes a best practice for innovation of IBD care practices. The consensus statements emerged offer a complex and integrated framework aimed to track the specificities of the psycho-social unmet needs of patients along their life-cycle and in the different phases of the patient journey. Early detection of psycho-social needs of patients is the first priority for achieving a truly patient centered and participate approach to IBD care. A second crucial step concerns the design and implementation of an organic approach to the promotion of patient and caregiver/family engagement. This approach requires not only the development of an effective information activity (literacy), but also of adequate psychological and psychosocial initiatives aimed at fostering active involvement in the management of IBD. To this end (third step), it is also necessary to educate and sensitize all the different healthcare professionals involved in the IBD care in order to support not only the Engagement of the patient/caregiver but also of the healthcare organizations in charge of the management of the disease (with specific attention to the hospital-territory connection). Fourth, a better sensitive and personalized use of the different digital health technologies today available can contribute to achieve these goals, but in the light of further education activities about a more proficient and aware use of such devices. Finally, an intervention on public opinion, stakeholders and health policy makers is important to improve the representation and management of IBD in society, free from the prejudices of the IBD stigma. In this perspective, the role of patient associations may play a fundamental role in such transformation process as a catalyst of the cultural shift required both from the healthcare professionals’ and the IBD patients’ side.

Limitations

Even if the consensus Statement process has been broad, deep and inclusive there were a few limitations. First, any generalizations from the literature review or workshops must be done carefully being that they represent the specific experience and perspectives of the individuals included in the process, and a forthcoming replica of the consensus process in a wider international scenario would be useful. Another limitation is connected to the national nature of this Consensus Conference: the habits of clinical practice of IBD may indeed change in different countries and local communities. Nonetheless, the participating experts have a reputable international clinical and scientific know how on the theme of the conference. Finally, these recommendations are not meant to be paradigmatic standards of practice. They are a scientific outline of best practices in the IBD sector. These recommendations should be taken as inspiring concepts to promote an effective engagement eco-system in IBD. Indeed, the most important stage of the process is the application of this principles in the day by day IBD practice through use of validated scientific instruments and practices.

Conclusions

Going beyond the indications illustrated and discussed in the previous paragraphs, a final remark can be made about the "usability" of the consensus conference as a tool to facilitate the promotion the psychological wellbeing and the engagement of patients in the context of IBD management.

Beyond the appropriate improvements of the process (see “Limitations” paragraph), we believe that three advantages of the consensus conference method can be electively recognized at the operational level: (a) the possibility of designing interventions closely related to the indications offered by scientific research; (b) the possibility of articulating at the organizational level the actors and the practices involved in the process of promoting engagement, by integrating the medical-clinical perspective with the psycho-social one; (c) finally, the possibility of building a shared course of action that is inclusive of all the actors (experts and lay people) involved in the process. We plan to disseminate these results through conferences, congresses and publications.

Availability of data and materials

All the data and materials are provided or referenced in the paper.

Abbreviations

- A.M.I.C.I. Onlus:

-

Associazione Nazionale per le Malattie Infiammatorie Croniche dell'Intestino

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IG-IBD:

-

Italian group for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases

- ISS:

-

Istituto Superiore di Sanità

References

Giulia R, Siew CN, Kotze PG, et al. Crohn’s disease (Primer). Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6(1).

Kawalec P, Malinowski KP. Indirect health costs in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2015.1011130.

Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel J-F, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1741–55.

Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Avedano L. IBD and health-related quality of life—discovering the true impact. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2014;8(10):1281–6.

Speedling EJ, Rose DN. Building an effective doctor-patient relationship: From patient satisfaction to patient participation. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(2):115–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90079-6.

Van den Bos G, Triemstra A. Quality of life as an instrument for need assessment and outcome assessment of health care in chronic patients. Qual Heal care QHC. 1999;8(4):247.

Eiser C, Morse R. A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84(3):205–11.

De Haes HCJM, Molenaar S. Patient participation and decision control. Med Decis Mak. 1997;17(3):353–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x9701700314.

Kim J. The effect of patient participation through physician’s resources on experience and wellbeing. Sustain. 2018; https://doi.org/10.3390/su10062102

Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; Fewer Data On Costs. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):207–14. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061.

Graffigna G, Barello S. Patient health engagement (PHE) model in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS): Monitoring patients’ engagement and psychological resilience in minimally invasive thoracic surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:S517–28. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.12.84.

Graffigna G, Barello S, Bonanomi A, et al. Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient’s level of activation. Haemophilia. 2009;8(6):353–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2.

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4p1):1005–1026. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ. 1999;318(7179):318–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7179.318.

Graffigna, G. SB. Engagement. Un Nuovo Modello Di Partecipazione in Sanità. (Il Pensiero Scientifico, ed.).; 2018.

Mikocka-Walus A, Massuger W, Knowles SR, et al. Psychological distress is highly prevalent in inflammatory bowel disease: A survey of psychological needs and attitudes. JGH Open. 2020;4(2):166–71.

Wortman PM, Vinokur A, Sechrest L. Do consensus conferences work? A process evaluation of the NIH consensus development program. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1988;13(3):469–98.

Volpato E, Bosio C, Previtali E, et al. The Evolution of IBD Perceived Engagement and Care Needs Across the Life-Cycle: A Scoping Review. 2020.

Graffigna G, Barello S, Riva G, et al. Recommandation for patient engagement promotion in care and cure for chronic conditions. [Promozione del patient engagement in ambito clinico-Assistenziale per le malattie croniche: raccomandazioni dalla prima conferenza di consenso italiana]. Recenti Prog Med. 2017;108(11):455–475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1701/2812.28441

O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework AU-Arksey Hilary. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Tynan AC, Drayton JL. Conducting focus groups—a guide for first‐time users. Mark Intell Plan. 1988.

Moradkhani A, Kerwin L, Dudley-Brown S, Tabibian JH. Disease-specific knowledge, coping, and adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1714-y.

Gumidyala AP, Plevinsky JM, Poulopoulos N, Kahn SA, Walkiewicz D, Greenley RN. What teens do not know can hurt them: an assessment of disease knowledge in adolescents and young adults with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(1):89–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000974.

Benchimol EI, Fortinsky KJ, Gozdyra P, Van Den Heuvel M, Van Limbergen J, Griffiths AM. Epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of international trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21349.

Greenley RN, Hommel KA, Nebel J, et al. A meta-analytic review of the psychosocial adjustment of youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp120.

Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: Findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1097/00054725-200608000-00005.

Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in iflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.20873.

Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, Hanes D, Wahbeh H. Depression and anxiety in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001.

Bokemeyer B, Hardt J, Hüppe D, et al. Clinical status, psychosocial impairments, medical treatment and health care costs for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Germany: An online IBD registry. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2012.02.014.

Jelenova D, Prasko J, Ociskova M, et al. Quality of life and parental styles assessed by adolescents suffering from inflammatory bowel diseases and their parents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:665–72.

Varni JW, Sherman SA, Burwinkle TM, Dickinson PE, Dixon P. The PedsQLTM family impact module: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(1):55.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Rajmil L, et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(10):1487–500.

Reigada LC, Moore MT, Martin CF, Kappelman MD. Psychometric evaluation of the IBD-specific anxiety scale: a novel measure of disease-related anxiety for adolescents with IBD. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43(4):413–22.

Sitarenios G, Kovacs M. Use of the Children’s Depression Inventory. 1999.

Szigethy E, Kenney E, Carpenter J, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and subsyndromal depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1290–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3180f6341f.

Keerthy D, Youk A, Srinath AI, et al. Effect of psychotherapy on health care utilization in children with inflammatory bowel disease and depression. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000001207.

Levy RL, van Tilburg MAL, Langer SL, et al. Effects of a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention trial to improve disease outcomes in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(9):2134–48. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000881.

van den Brink G, Stapersma L, El Marroun H, et al. Effectiveness of disease-specific cognitive-behavioural therapy on depression, anxiety, quality of life and the clinical course of disease in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial (HAPPY-I. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1): e000071. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgast-2015-000071.

Szigethy E, Whitton SW, Levy-Warren A, DeMaso DR, Weisz J, Beardslee WR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(12):1469–77. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000142284.10574.1f.

Jelenova D, Prasko J, Ociskova M, et al. Psychoeducation of adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseases and their families. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2016;58(1):33–9.

D’Amico F, Rahier J-F, Leone S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Views of patients with inflammatory bowel disease on the COVID-19 pandemic: a global survey. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(7):631–2.

McCartney S. Inflammatory bowel disease in transition: challenges and solutions in adolescent care. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2011;2(4):237–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/fg.2010.002741.

Gray WN, Resmini AR, Baker KD, et al. Concerns, barriers, and recommendations to improve transition from pediatric to adult IBD care: Perspectives of patients, parents, and health professionals. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000419.

Elkins G, Whitfield P, Marcus J, Symmonds R, Rodriquez J, Cook T. Noncompliance with behavioral recommendations after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(3):287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2005.03.186.

Cho R, Wickert NM, Klassen AF, Tsangaris E, Marshall JK, Brill H. Identifying needs in young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2018;41(1):19–28.

Donegan A, Boyle B, Crandall W, et al. Connecting families: a pediatric IBD center’s development and implementation of a volunteer parent mentor program. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(5):1151–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000733.

Timmer A, de Sordi D, Menke E, et al. Modeling determinants of satisfaction with health care in youth with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional survey. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1289.

Mayberry JF, Lobo A, Ford AC, Thomas A, Group GD. NICE clinical guideline (CG152): the management of Crohn’s disease in adults, children and young people. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(2):195–203.

Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Heal. 1993;14(7):570–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(93)90143-D.

Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009794.pub2.

Cooley WC. Adolescent health care transition in transition. JAMA Pediatr. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2578.

Afzali A, Wahbeh G. Transition of pediatric to adult care in inflammatory bowel disease: Is it as easy as 1, 2, 3? World J Gastroenterol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i20.3624.

Cole R, Ashok D, Razack A, Azaz A, Sebastian S. Evaluation of outcomes in adolescent inflammatory bowel disease patients following transfer from pediatric to adult health care services: case for transition. J Adolesc Health; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.012

van Tilburg MAL, Claar RL, Romano JM, et al. Psychological factors may play an important role in pediatric Crohn’s disease symptoms and disability. J Pediatr. 2017;184:94–100.

Vedrana V, Bramhagen A-C, Idvall E, Wennick A. Swedish Children’s lived experience of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/SGA.0000000000000295.

Reigada LC, Bruzzese J, Benkov KJ, et al. Illness-specific anxiety: Implications for functioning and utilization of medical services in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2011;16(3):207–15.

Zmeskalova D, Prasko J, Holubova M, et al. Unmet psychosocial needs in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2016;37(5):395–402.

Guilfoyle SM, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Paediatric parenting stress in inflammatory bowel disease: application of the Pediatric Inventory for Parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01200.x.

Guilfoyle SM, Gray WN, Herzer-maddux M, Hommel KA. Parenting stress predicts depressive symptoms in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26964–971(26):964–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000149.

Wang Z, Zhong J, Zhou X, et al. Illness perceptions and stress: mediators between disease severity and psychological well-being and quality of life among patients with Crohn’s disease. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2387–96. https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s118413.

Lindström C, Åman J, Anderzén-Carlsson A, Lindahl NA. Group intervention for burnout in parents of chronically ill children – a small-scale study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016;30(4):678–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12287.

Halmos EP, Gibson PR. Dietary management of IBD—insights and advice. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(3):133.

García-Vega E, Fernandez-Rodriguez C. A stress management programme for Crohn’s disease. Behav Res Ther. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00146-3.

Morar P, Read J, Arora S, et al. Defining the optimal design of the inflammatory bowel disease multidisciplinary team: results from a multicentre qualitative expert-based study. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2015;6(4):290. https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2014-100549.

Stansfield C, Robinson A, Lal S. The impact of a nurse co-ordinated ibd multidisciplinary team meeting in enhancing safety and reducing cost. Gut. 2015;64(Suppl 1):A96. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309861.196.

Lemberg DA, Day AS. Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis in children: An update for 2014. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51(3):266–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12685.

Parekh NK, Shah S, McMaster K, et al. Effects of caregiver burden on quality of life and coping strategies utilized by caregivers of adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30(1):89–95. https://doi.org/10.20524/aog.2016.0084.

Porcell P, Leoci C, Guerra V. A prospective study of the relationship between disease activity and psychologic distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(8):792–6.

Gamwell KL, Baudino MN, Bakula DM, et al. Perceived illness stigma, thwarted belongingness, and depressive symptoms in youth with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(5):960–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy011.

Goodhand JR, Greig FIS, Koodun Y, et al. Do antidepressants influence the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease? A retrospective case-matched observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21846.

Moser G. Should we incorporate psychological care into the management of IBD? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep0549.

Filipović BR, Filipović BF, Kerkez M, Milinić N, Randelović T. Depression and anxiety levels in therapy-naïve patients with inflammatory bowel disease and cancer of the colon. World J Gastroenterol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.438.

Muller KR, Prosser R, Bampton P, Mountifield R, Andrews JM. Female gender and surgery impair relationships, body image, and sexuality in inflammatory bowel disease: Patient perceptions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21090.

Pittet V, Vaucher C, Froehlich F, et al. Patient self-reported concerns in inflammatory bowel diseases: a genderspecific subjective quality-of-life indicator. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171864.

Norton C, Czuber-Dochan W, Bassett P, et al. Assessing fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease: comparison of three fatigue scales. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13255.

Keefer L, Taft T. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.2147/ceg.s83533.

Leso V, Ricciardi W, Iavicoli I. Occupational risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(15):2838–51.

Hood MM, Keshavarzian A. Sleep quality in ulcerative colitis: associations with inflammation, Psychological Distress , and Quality of Life. 2018.

Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(9):1882–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21580.

Kakodkar S, Mutlu EA. Diet as a therapeutic option for adult inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):745–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2017.08.016.

Schreiner P, Yilmaz B, Rossel J-B, et al. Vegetarian or gluten-free diets in patients with inflammatory bowel disease are associated with lower psychological well-being and a different gut microbiota, but no beneficial effects on the course of the disease. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(6):767–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050640619841249.

Limdi JK, Aggarwal D, McLaughlin JT. Dietary practices and beliefs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(1):164–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000585.

Ng V, Millard W, Lebrun C, Howard J. Low-intensity exercise improves quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin J Sport Med Off J Can Acad Sport Med. 2007;17(5):384–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0b013e31802b4fda.

Klare P, Nigg J, Nold J, et al. The impact of a ten-week physical exercise program on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Digestion. 2015;91(3):239–47. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371795.

Goodhand JR, Wahed M, Rampton DS. Management of stress in inflammatory bowel disease: a therapeutic option? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1586/egh.09.55.

Von Wietersheim J, Kessler H. Psychotherapy with chronic inflammatory bowel disease patients: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mib.0000236925.87502.e0.

McCombie AM, Mulder RT, Gearry RB. Psychotherapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review and update. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2013;7(12):935–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.004.

Knowles SR, Monshat K, Castle DJ. The efficacy and methodological challenges of psychotherapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0b013e318296ae5a.

Ewais T, Begun J, Kenny M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness based interventions and yoga in inflammatory bowel disease. J Psychosom Res. 2019;116(November):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.010.

Britt RK, Britt RK. Online social support for participants of Crohn ’ s and ulcerative colitis groups online social support for participants of Crohn ’ s and ulcerative colitis groups. Health Commun. 2017;32(12):1529–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1234539.

Limdi JK. Dietary practices and inflammatory bowel disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37(4):284–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-018-0890-5.

Loudon CP, Corroll V, Butcher J, Rawsthorne P, Bernstein CN. The effects of physical exercise on patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):697–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00939.x.

Chrobak-Bień J, Gawor A, Paplaczyk M, Małecka-Panas E, Gąsiorowska A. Analysis of factors affecting the quality of life of those suffering from Crohn’s disease. Pol Przegl Chir. 2017;89(4):16–22.

Gregory VL Jr. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with implications for clinical social work. J Evid Based Soc Work. 2019;16(4):363–85.

Bernstein KI, Promislow S, Carr R, Rawsthorne P, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Information needs and preferences of recently diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21363.

Wong S, Walker JR, Carr R, et al. The information needs and preferences of persons with longstanding inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/735386.

Wu Q, Zhong J. Disease-related information requirements in patients with Crohn’s disease. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1579–86. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S169706.

Tormey LK, Reich J, Chen YS, et al. Limited health literacy is associated with worse patient-reported outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(1):204–12.

Butcher RO, Law TL, Prudham RC, Limdi JK. Patient knowledge in inflammatory bowel disease: CCKNOW, how much do they know? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(10):E131–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21810.

Leone D, Menichetti J, Fiorino G, Vegni E. State of the art: psychotherapeutic interventions targeting the psychological factors involved in IBD. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15(11):1020–9. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450115666140627151702.

Ewais T, Begun J, Kenny M, et al. Protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in youth with inflammatory bowel disease and depression. BMJ Open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025568.

Carpio D, López-Sanromán A, Calvet X, et al. Perception of disease burden and treatment satisfaction in patients with ulcerative colitis from outpatient clinics in Spain: UC-LIFE survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(9):1056–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000658.

Squires SI, Boal AJ, Lamont S, Naismith GD. Implementing a self-management strategy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): patient perceptions, clinical outcomes and the impact on service. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2017;8:272–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2017-100807.

Hait E, Arnold JH, Fishman LN. Educate, communicate, anticipate—practical recommendations for transitioning adolescents with IBD to adult health care. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(1):70–3.

Kluthe C, Isaac DM, Hiller K, et al. Qualitative analysis of pediatric patient and caregiver perspectives after recent diagnosis with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:106–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.11.011.

Khan S, Dasrath F, Farghaly S, et al. Unmet communication and information needs for patients with ibd: implications for mobile health technology. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;12(3):1–11. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMMR/2016/21884.

Carlsen K, Jakobsen C, Houen G, et al. Self-managed eHealth disease monitoring in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease : a randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000001026.

Sieverink F, Kelders SM, van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC. Clarifying the concept of adherence to eHealth technology: systematic review on when usage becomes adherence. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(12):e402.

Aguas M, Del Hoyo J, Faubel R, et al. A web-based telemanagement system for patients with complex inflammatory bowel disease: protocol for a randomized controlled clinical trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(12): e190. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.9639:10.2196/resprot.9639.

Bossuyt P, Pouillon L, Bonnaud G, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. E-health in inflammatory bowel diseases: more challenges than opportunities? Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(12):1320–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2017.08.026.

Bossuyt P, Pouillon L, Peyrin-biroulet L. Primetime for e-health in IBD? Nat Publ Gr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.11.

Akobeng AK, Leary NO, Vail A, et al. EBioMedicine telephone consultation as a substitute for routine out-patient face-to-face consultation for children with inflammatory bowel disease: randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:1251–6.

Heida A, Dijkstra A, Groen H, Kobold AM, Verkade H, Rheenen P Van. Comparing the efficacy of a web-assisted calprotectin-based treatment algorithm ( IBD-live ) with usual practices in teenagers with inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial Comparing the efficacy of a web-assisted calp. 2015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0787-x

George LA, Cross RK. Remote monitoring and telemedicine in IBD: are we there yet? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(3):12.

Baker DM, Lee MJ, Jones GL, Brown SR, Lobo AJ. The Informational needs and preferences of patients considering surgery for ulcerative colitis: results of a qualitative study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(1):179–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izx026.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank AMICI Onlus and IG-IBD (Italian Group for Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Diseases) and ISS (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) for their support to the project.

Funding

This project has been funded by AMICI Onlus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GG and CB drafted the paper with the contribution of FP and EV. All the authors reviewed and approved the final draft of the paper before the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the Italian regulations, in terms of ethical approvals we follow the rules established by the Italian Association of Psychology. According to article 11, studies such as expert panels do not require the approval from local Ethics Committees.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

S Danese has served as a speaker, consultant, and advisory board member for Schering-Plough, AbbVie, Actelion, Alphawasserman, AstraZeneca, Cellerix, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Genentech, Grunenthal, Johnson and Johnson, Millenium Takeda, MSD, Nikkiso Europe GmbH, Novo Nordisk, Nycomed, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, UCB Pharma and Vifor. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Consensus conference organizational chart

Institutional representatives: A.M.I.C.I. Onlus; EngageMinds HUB—Consumer, Food & Health Engagement Research Center Sacred Heart Catholic University—Milan; Istituto Superiore di Sanità.

Promoting committee: S. Leone, A.M.I.C.I. Onlus; E. Previtali A.M.I.C.I. Onlus; G. Graffigna, EngageMinds HUB, Consumer, Food & Health Engagement Research Center, Sacred Heart Catholic University; M. Boirivant, Istituto Superiore di Sanità; S. Brusaferro, Istituto Superiore di Sanità.

Technical and scientific committee

-

Tonino Aceti|FNOPI (National Federation of Orders of Nursing Professions)

-

Alessandro Armuzzi|IG-IBD (Italian Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease)

-

Livia Biancone| “Tor Vergata" University of Rome

-

Piero Cai|Policlinico San Martino IRCCS Hospital

-

Elena Carnevali|Social Affairs Commission Chamber of Deputies

-

Liliana Coppola|Region of Lombardy

-

Silvio Danese|Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano|Past president ECCO

-

Luigi Dall’Oglio|Pediatric Hospital Bambino Gesù, Roma

-

Santo Di Nuovo|AIP (Italian Association of Psychology)

-

Giulio Gallera|Region of Lombardy

-

Maria Alessandra Gallone|Republic Senate

-

Antonio Gaudioso|Secretary General Cittadinanzattiva

-

Antonio Gasbarrini|Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome

-

Fulvio Giardina|CNOP (National Council Order Psychologists)

-

David Lazzari|CNOP President

-

Paolo Lionetti|Full Professor of Pediatrics University of Florence, Head of Gastroenterology and Nutrition SOD Meyer Pediatric Hospital

-

Beatrice Mazzoleni|IPASVI (Professional Nurses, Health Care Assistants, Child Care Workers)

-

Enrico Molinari|Sacred Heart Catholic University, Auxological Institute of Milan

-

Giovanni Muttillo|IPASVI (Professional Nurses, Health Care Assistants, Child Care Workers)

-

Gilberto Poggioli|Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, Policlinico Sant'Orsola Bologna

-

Claudio Romano|University of Messina

-

Maria Rizzotti|Republic Senate

-

Gabriele Roveron|AIOSS (Italian Association of Health Operators of Stomatherapy)

Work groups

Group on psychosocial support needs in the child with IBD

-

Marina Aloi|La Sapienza University, Rome

-

Claudia Canaletti|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Eleonora Geccherle|Sacro Cuore Don Calabria" Hospital Negrar” (VR)

-

Giammarco Mocci|G. Brotzu" Hospital, Cagliari

-

Lorenzo Norsa|ASST Hospital Pope John XXIII, Bergamo

-

Francesca Maria Onidi|G. Brotzu" Hospital, Cagliari

-

Floriana Perillo|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Sonia Storoni|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

Group on psychosocial interventions to support the child with IBD

-

Enrica Atzori|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Matteo Bramuzzo|IRCCS «Burlo Garofolo», Trieste

-

Gionata Fiorino|Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano

-

Simona Gatti|Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti of Ancona

-

Antonino Morabito|Meyer University Hospital, Florence

-

Maria Simonetta Spada|ASST Hospital Pope John XXIII, Bergamo

-

Claudia Venditti|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

Group on psychosocial support needs in adults with IBD

-

Giovanna Artioli|IPASVI (Professional Nurses, Health Care Assistants, Child Care Workers)

-

Concetta Balzotti|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Luciano Bertolusso|FIMMG (Italian Federation of General Practitioners)

-

Gaia Campanale|ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, University of Milan

-

Federico Colombo|IMIPSI (Milanese Institute of Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy)

-

Renata D’Incà|Hospital of Padua

-

Manuela Pes|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Simona Radice|Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano

-

Elena Vegni|State University of Milan

Group on psychosocial interventions to support the adult with IBD

-

Alessandro Agostini|DIMES (Department of Specialistic, Diagnostic, Experimental Medicine), University of Bologna

-

Flavio Caprioli|Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Policlinico di Milano

-

Giuseppe Coppolino|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Antonio Di Sabatino|Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Pavia

-

Maria Galanti|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Daniele Napolitano|Agostino Gemelli Foundation University Hospital, Rome

-

Gaspare Solina|Azienda Ospedaliera Ospedali Riuniti Villa Sofia Cervello, Palermo

-

Marinella Sommaruga|CNOP (Consiglio Nazionale Ordine Psicologi)

Group on the definition of technology in the psychosocial care of the patient with IBD

-

Andrea Dessì|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

Anna Kohn|IG-IBD (Italian Group for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease)

-

Filippo Mocciaro|ARNAS Civico Di Cristina, Palermo

-

Claudia Repetto|Sacred Heart Catholic University

-

Luigi Sofo|Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS Università cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome

-

Antonino Spinelli|Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano

Jury panel

-

Patrizia Alvisi|SIGENP (Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition)

-

Gianluca Castelnuovo|AIP (Italian Association of Psychology)

-

Antonella Celano|APMARR (National Association of People with Rheumatologic and Rare Diseases)

-

Marco Daperno|General Secretary IG-IBD|Vice-Chairman of the Jury Panel

-

Ferdinando Ficari|Careggi University Hospital, Florence

-

Anna Lisa Mandorino|Deputy Secretary Cittadinanzattiva|Secretary of the Jury Panel

-

Paolo Michielin|University of Padua, AIAMC (Italian Association of Behavior Analysis and Modification and Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy)

-

Giuseppe Parisi|SIPeM (Italian Society of Medical Pedagogy)

-

Paola Pisanti|Ministry of Health Chronic Disease Consultant|Chairman of the Jury Panel

-

Alessandra Tongiorgi|Pisana University Hospital

-

Silvia Tonolo|ANMAR (National Association of Rheumatic Diseases)

Writing committee: A. Celano, A. Tongiorgi

-

Antonella Celano|APMARR (National Association of People with Rheumatologic and Rare Diseases)

-

Alessandra Tongiorgi|Pisana University Hospital

Methodological support

-

F. Pagnini|Sacred Heart Catholic University – Milan (Coordinator)

-

C. Bosio|EngageMinds HUB—Sacred Heart Catholic University

-

E. Volpato|Sacred Heart Catholic University—Milan

Scientific-organizational coordination center

Scientific secretariat

-

C. Bosio| EngageMinds HUB—Sacred Heart Catholic University

Organizational secretariat

-

M. Rizzi|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

N. Fiumanò|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

-

C. Ranghetti|A.M.I.C.I. Onlus

Appendix 2: The literature review process

Method | Literature review according to the principles of scoping review methodology [20, 21] |

Search string | ("IBD*" OR "inflammatory bowel disease*" OR "Crohn*" OR "ulcerative colitis") AND ("Psych*" OR "social*" OR "famil*" OR "Engagement" OR "empowerment") AND ( "intervention" OR "trial" OR "program" OR "strategy*" OR "counsel*" OR "treatment" OR "support “) |

Queried databases | Health and Life Sciences, Social Sciences and Medical Sciences, such as PubMed, Medline, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane, Web of Science, PsychInfo |

Inclusion criteria | Years considered: 2009–2019; language: English (recognized language of international scientific debate); types of articles: qualitative or quantitative studies published in peer-reviewed journals, commentaries, letters, editorials; ethical aspects: studies approved by Ethics Committees; age groups considered: pediatric (< 18 years), adult (≥ 18 years and < 60 years), and elderly patients (≥ 60 years); population: chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD); focus of the literature: studies that explicitly discuss priority social care and psychological needs, best practices for a social care intake, the concept of Patient Engagement, studies on social and/or psychological strategies that value the patient's point of view and experience, studies that present a clear theoretical framework on patient experience, studies that focus on the experience of using care, quality of life indicators and monitoring, in the context of the chronic diseases considered |

Analysis | Structured analysis grid following a mixed-methods approach given the qualitative and quantitative nature of the studies included: (1) methodological characteristics of the study (e.g., year of publication, country of first author, study design, no. of participants); (2) characteristics of the participants (e.g., diagnosis, age range, presence of caregivers); (3) characteristics of the social and psychological needs (e.g., for which transition phase, type of need expressed, theoretical framework considered); (4) characteristics of the social and/or psychological strategy (if present: type of strategy, tools used, group or individual, theoretical foundations thereof). (4) characteristics of the social and/or psychological strategy (if any: type of strategy, tools used, group or individual, theoretical foundations of the same); (5) results obtained (e.g. outcomes measured, method of evaluating results, overall results achieved) |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Graffigna, G., Bosio, C., Pagnini, F. et al. Promoting psycho-social wellbeing for engaging inflammatory bowel disease patients in their care: an Italian consensus statement. BMC Psychol 9, 186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00692-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00692-6