Abstract

Background

In the criminal justice system, special populations, such as older adults or patients with infectious diseases, have been identified as particularly vulnerable to poor health outcomes. Military veterans involved in the criminal justice system are also a vulnerable population warranting attention because of their unique healthcare needs. This review aims to provide an overview of existing literature on justice-involved veterans’ health and healthcare to identify research gaps and inform policy and practice.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted to identify research articles related to justice-involved veterans’ health and healthcare that were published prior to December 2017. Study characteristics including healthcare category, study design, sample size, and funding source were extracted and summarized with the aim of providing an overview of extant literature.

Results

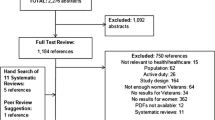

The search strategy initially identified 1830 unique abstracts with 1387 abstracts then excluded. Full-text review of 443 articles was conducted with 252 excluded. There were 191 articles included, most related to veterans’ mental health (130/191, 68%) or homelessness (24/191, 13%). Most studies used an observational design (173/191, 91%).

Conclusions

Knowledge gaps identified from the review provide guidance on future areas of research. Studies on different sociodemographic groups, medical conditions, and the management of multiple conditions and psychosocial challenges are needed. Developing and testing interventions, especially randomized trials, to address justice-involved veterans care needs will help to improve their health and healthcare. Finally, an integrated conceptual framework that draws from diverse disciplines, such as criminology, health services, psychology, and implementation science is needed to inform research, policy and practice focused on justice-involved veterans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Public significance statement

Of 191 research articles published on the health and healthcare of veterans involved in the criminal justice system, the majority examined veterans’ mental health. Studies are needed that address challenges faced by different sociodemographic groups of veterans who are in the justice system and interventions that help them manage multiple mental health, substance use disorder, and medical conditions.

Special populations in the criminal justice system

In the criminal justice system, vulnerable populations, such as women (Binswanger et al., 2010; Timko et al., 2019), older adults (Skarupski, Gross, Schrack, Deal, & Eber, 2018), and people with HIV or hepatitis C (Spaulding, Anderson, Khan, Taborda-Vidarte, & Phillips, 2017), are at risk of poor health outcomes. Although these groups have been the focus of numerous research studies, another vulnerable group – military veterans in the criminal justice system – only recently gained attention. Justice-involved veterans, which are military veterans detained by or under the supervision of the criminal justice system (e.g., incarcerated in jail or prison, supervised by probation or parole), are a special population who comprise approximately 8% of the incarcerated population in the U.S. (Bronson, Carson, Noonan, & Berzofsky, 2015). There are an estimated 181,500 veterans incarcerated in prisons and jails.

Background on justice-involved veterans

Justice-involved veterans have extensive medical, mental health and substance use disorder treatment needs. Among veterans age 55 and older who were exiting prison, 50% had hypertension, 20% had diabetes, and 16% had hepatitis (Williams et al., 2010). In 2007, the Veterans Health Adminstration (VHA) implemented the Veterans Justice Programs, which are designed to connect justice-involved veterans with a broad range of VHA and community healthcare and related services. More than half of veterans seen by these programs are diagnosed with mental health or substance use disorders after entering VHA treatment (Finlay et al., 2016, 2017). The mortality risk among veterans exiting prison is similar to that of non-veterans exiting prison, 12 times higher than that of the general population, with overdose as the leading cause of death (Wortzel, Blatchford, Conner, Adler, & Binswanger, 2012).

In addition to healthcare treatment needs, justice-involved veterans face numerous psychosocial problems. Among veterans in prison, 30% have a history of homelessness (Tsai, Rosenheck, Kasprow, & McGuire, 2014). Housing can be difficult to find after incarceration, especially for veterans with registered sex offenses (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015). Finding and maintaining employment can also be difficult. Challenges include legal restrictions on employment, stigma and criminal background checks, and competing needs and health conditions (McDonough, Blodgett, Midboe, & Blonigen, 2015). Finally, an estimated 10% of incarcerated veterans are not eligible for VHA services due to dishonorable/bad conduct or other discharge records from military service, and an additional 13% may not be eligible due to other than honorable discharge status (Bronson et al., 2015). These veterans may face the same challenges to finding healthcare as other justice-involved populations, including lack of insurance, limited community treatment options, or other competing challenges, such as finding and maintaining housing and employment (Mallik-Kane & Visher, 2008).

Importance of examining justice-involved veterans

Examining the health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans is important for at least three reasons. First, veterans may have different healthcare treatment needs than civilians involved in the justice system because of combat or other traumatic events they experienced while in the military (Backhaus, Gholizadeh, Godfrey, Pittman, & Afari, 2016), which may have increased their risk for involvement in the criminal justice system. Second, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and society at large, has an obligation to care for veterans, including justice-involved veterans. Third, communities will be safer and save resources when the care needs of justice-involved veterans are addressed. Understanding the health and healthcare needs of incarcerated and other justice-involved veterans will allow the VHA and other settings in which veterans seek health care to design programming that will be responsive to the treatment priorities of these veterans.

Differences between veterans and non-veterans

Prior research suggests some connection between military service and criminal justice involvement, which may be explained by profiles of those who volunteer for military service, traumatic experiences during military service, and medical, mental health, or substance use disorder conditions related to military service. People who volunteer for the military have higher odds of becoming incarcerated than people who do not join the military (Culp, Youstin, Englander, & Lynch, 2013). Pre-existing differences in people who join the military may also explain how type of crime committed varies by military status. Compared to non-veterans, a higher percentage of veterans were incarcerated in US prisons and jails for sexual offenses, but a lower percentage were incarcerated for property and drug offenses (Bronson et al., 2015). In Arizona, a higher percentage (30%) of veterans were arrested for a violent offense compared to non-veterans (20%) (White, Mulvey, Fox, & Choate, 2012).

Traumatic experiences and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been linked with criminal justice involvement (Backhaus et al., 2016; Donley et al., 2012; Edalati & Nicholls, 2017; MacManus et al., 2013) and may explain the link between military service and criminal behaviors. People who select into the military may come from a background where they experienced more trauma. For example, compared to non-veterans, veterans experienced more adverse events in childhood (Katon et al., 2015). Among veterans in jail, 87% had experienced a lifetime traumatic event and 39% screened positive for PTSD (Saxon et al., 2001). In addition, exposure to combat or other traumatic situations may occur during military service. Among veterans in jail, 58% of men and 38% of women had served in a combat zone (Stainbrook, Hartwell, & James, 2016). Exposure to more traumatic events during military service and PTSD were linked with a higher risk of violent offending among veterans in the United Kingdom (MacManus et al., 2013). PTSD symptoms have been linked with interpersonal violence (Hoyt, Wray, & Rielage, 2014) and other criminal justice involvement among veterans (Brown, 2011) and civilians (Donley et al., 2012).

Health conditions related to military service may also be linked to criminal justice involvement. Traumatic brain injury, a signature injury of recent military conflicts (Snell & Halter, 2010), is associated with criminal behaviors, such as violent offending (Williams et al., 2018). Substance use disorders have been linked with recidivism among justice-involved veterans in the US (Blonigen et al., 2016; Tsai, Finlay, Flatley, Kasprow, & Clark, 2018) and post-deployment alcohol use has been associated with violent offending among veterans in the United Kingdom (MacManus et al., 2013). Among US veterans who served in recent conflicts in Iraq or Afghanistan, combat-related PTSD was linked with a high risk of incarceration (Tsai, Rosenheck, Kasprow, & McGuire, 2013a).

Health differences between criminal justice involved veterans and non-veterans

There are few health differences between justice-involved veterans and non-veterans. In a sample of older adults leaving jail, prevalence rates of medical, mental health and substance use disorders were similar between incarcerated veterans and non-veterans, except veterans had a higher prevalence of asthma and PTSD (Williams et al., 2010). A nationally representative sample of men incarcerated in prisons and jails indicated that veterans had higher prevalence of a history of PTSD and personality disorders than non-veterans, but did not differ on a history of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or anxiety disorder (Bronson et al., 2015). Veterans and non-veterans released from prison shared a similar risk of death in the weeks immediately following release, though this risk was attenuated for veterans with VA benefits (Wortzel et al., 2012).

Prior reviews on justice-involved veterans

Although there are prior reviews studies on justice-involved veterans, a scoping review has not yet been conducted. Scoping reviews aim to give a comprehensive view of the extant literature and identify gaps in research to inform research agendas and policy and practice (Arskey & O'Malley, 2005; Tricco et al., 2016). Prior reviews examined justice-involved veterans from a social work perspective (Canada & Albright, 2014), the socio-cultural and psychological aspects of military service and justice involvement (Brown, Stanulis, Theis, Farnsworth, & Daniels, 2013), the link between criminal behavior and military experience from a legal perspective (Holbrook & Anderson, 2011), the legal and clinical implications of PTSD among combat veterans (Fine & Levin, 2008; Marciniak, 1986), arrest rates among Vietnam veterans (Beckerman & Fontana, 1989), and theoretical models explaining criminal justice involvement among veterans with a summary of existing justice-related programming for veterans (Stacer & Solinas-Saunders, 2015). However, these reviews were not systematic. A few systematic reviews on specific topics related to justice-involved veterans have been conducted, including studies examining suicide risk (Wortzel, Binswanger, Anderson, & Adler, 2009), recidivism risk (Blonigen et al., 2016), and the prevalence of mental health disorders (Blodgett et al., 2015). A protocol for a systematic review to examine risk of criminal justice involvement among veterans with mental health and substance use disorder conditions was published by Taylor, Parkes, Haw, and Jepson (2012).

Aims

The aim of the current study was to conduct a scoping review of the literature related to the health and healthcare of military veterans involved in the criminal justice system.. Accordingly, the purposes of this study were to: (1) Summarize and synthesize the extent and characteristics of the existing literature across multiple fields, and (2) Identify research gaps to be addressed in future research efforts. The results of this study will help guide future research in this area and inform policy and practice. Additionally, this reviewed literature can serve as a resource for researchers, legal professionals, healthcare providers, and other professionals who work with justice-involved veterans.

Methods

The population of interest was justice-involved veterans, both in the US and internationally. As our aim was to summarize and synthesize the existing literature, we included all comparators, interventions, settings, and outcomes, but we did not evaluate, aggregate, or present study findings. Ethical approval is not required as our study includes only published peer-reviewed manuscripts and reports.

Data sources and searches

Following a modified version of the PRISMA guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009) and guidelines for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2015), we used a variety of search mechanisms to find articles related to justice-involved veterans. We searched five databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, and PsychINFO. Keywords included veterans or former military, and criminal justice-related terms such as prison, jail, court, or probation with no restrictions on dates searched (see the Additional file 1 for search algorithms and terms used). The initial search was implemented on June 2, 2017. We also created alerts in the selected search engines and added articles through the study period ending November 30, 2017. During the summer of 2017, we queried experts in the field with requests for articles from their personal files. Finally, we mined references from articles to identify any missing work.

Study selection

We excluded studies that did not include justice-involved veterans, were not relevant to health or healthcare, or were limited to active duty military personnel. Consistent with previous studies (Danan et al., 2017), we excluded several article types. Case reports, law articles/briefs, and meeting abstracts were excluded because most did not contain sufficient study description or results. Editorials, letters, protocols, and literature or systematic reviews were excluded because they did not include original empirical results. We also excluded brief news articles that did not report original results and articles that were not in English or without a published English translation. We included non-peer-reviewed publications if they were publicly available in a published form (e.g., government reports) and dissertations if they were publicly available and exhibited scientifically rigorous methods, but unpublished papers that were neither government reports or dissertations were excluded.

Prior to abstract review, duplicates were removed. The lead author (AKF) reviewed all abstracts with a co-investigator (MDO or CT) providing a secondary review. Any differences in agreement were discussed and resolved. Rayyan was used to review abstracts (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, 2016). Full-text articles were obtained for the selected abstracts, and each article was independently reviewed by an investigator or research assistant. The lead author independently reviewed a 10% random sample of full-text articles that were reviewed by another investigator or research assistant and reviewed any additional articles when asked by the first reviewer. Any studies that raised questions were discussed among the research team to reach agreement.

Data extraction

For studies that were selected for inclusion at the full-text stage, an investigator or research assistant extracted 14 study characteristics. We selected and defined these characteristics based on prior studies (Danan et al., 2017) and by conducting extraction with a subsample of articles and discussing potential characteristics to include. The final extracted characteristics were: (1) healthcare category, (2) study design, (3) sample size, (4) percentage of veterans, (5) number of justice-involved veterans, (6–8) reporting of gender, race and age, (9) research setting, (10) period of military service, (11) outcomes reported, (12) funding source, (13) country, and (14) period of data collection.

Data synthesis and analysis

We summarized the selected studies across characteristics. Consistent with the aims of a scoping review, our results present an overview of the extant literature, but we do not examine individual studies. Thus, we did not assess for risk of bias nor did we analyze the strength of the evidence.

Results

In total, we reviewed 1830 abstracts and excluded 1387 abstracts (Fig. 1). We reviewed full-texts of 443 articles, of which 252 were excluded. All included studies are listed in Table 1 and summarized by healthcare category, sample size, study design, and funding source. The majority of studies were related to mental health (130/191, 68%) or homelessness (24/191, 13%). There were 49 studies (26%) published prior to 2000, 55 articles (29%) published from 2000 to 2012, and 86 articles (45%) published from 2013 to 2017. The majority (133/191, 70%) of articles drew from samples in VHA treatment settings or programs, but the remaining 30% were conducted in other settings where justice-involved veterans seek healthcare including jails, prisons, courts, and community treatment settings.

Healthcare category

Mental health conditions

Substance use disorders were the most common conditions examined in studies, including studies focused solely on veterans with alcohol use disorder (Finlay et al., 2018; McQuaid et al., 2000; Moore, Fuehrlein, & Rosenheck, 2017; Richards, Goldberg, Anderson, & Rodin, 1990), opioid use disorder (Craig, 1980; Finlay et al., 2016; Rothbard et al., 1999), or co-occurring substance use and other mental health diagnoses (Mohamed, 2013; Timko, Finlay, Schultz, & Blonigen, 2017; Wenzel et al., 1996). Some studies investigated the prevalence of multiple mental health and substance use disorder conditions, reporting on these conditions and healthcare utilization among justice-involved veterans (e.g., Finlay et al., 2017; Finlay, Smelson, et al., 2016).

Several articles focused on conditions and experiences related to military service such as PTSD and trauma (Backhaus et al., 2016; Bennett, Morris, Sexton, Bonar, & Chermack, 2018; Elbogen et al., 2012; Saxon et al., 2001; Sigafoos, 1994). A number of observational studies addressed violence (Elbogen et al., 2012; Hoyt et al., 2014; MacManus et al., 2013) and Veterans Treatment Courts (Clark, Blue-Howells, & McGuire, 2014; Knudsen & Wingenfeld, 2016; Tsai, Flatley, Kasprow, Clark, & Finlay, 2017). Only one study we identified examined suicide as the primary outcome (Ilgen, Harris, Moos, & Tiet, 2007), though another study addressed suicide along with other factors (Kimbrel et al., 2014).

Homelessness

Studies were coded as fitting the healthcare category of Homelessness when the samples examined were homeless veterans (i.e., veterans who were homeless prior to treatment or who were receiving homeless services) or the study’s primary focus was to examine homelessness. The majority of participants in these studies were currently or previously justice-involved and/or their criminal justice involvement was a primary or secondary factor in the study. Often these veterans were recruited from VHA clinical settings, such as addiction treatment programs (Benda, Rodell, & Rodell, 2003a) or mental health inpatient care (e.g., Douyon et al., 1998), or were from VHA homeless programs (e.g., Cusack & Montgomery, 2017; Gabrielian et al., 2016; Tsai, O'Connell, Kasprow, & Rosenheck, 2011), although four studies were conducted in non-VHA settings (e.g., Montgomery, Szymkowiak, Marcus, Howard, & Culhane, 2016; Williams et al., 2010). Mental health and substance use disorders were the most commonly addressed issues among these studies, though some studies also examined medical conditions.

Access & utilization

Of the 14 articles that examined access and utilization, half reported on healthcare service use, such as treatment utilization among veterans with PTSD who recently returned from military service in Iraq or Afghanistan (DeViva, 2014), differences in treatment use among veterans who received VHA outreach services while in jail compared to veterans who received VHA outreach services in settings to address homelessness (McGuire, Rosenheck, & Kasprow, 2003), and health services utilization among veterans who received medical-legal partnership services (Tsai et al., 2017). Five of the studies occurred in non-VHA settings, including prison (Wainwright, McDonnell, Lennox, Shaw, & Senior, 2017; Wortzel et al., 2012), an emergency shelter (Petrovich, Pollio, & North, 2014), and courts (Shannon et al., 2017; Trojano, Christopher, Pinals, Harnish, & Smelson, 2017). Three articles described barriers to and facilitators of healthcare for justice-involved veterans (Blonigen et al., 2018; Butt, Wagener, Shakil, & Ahmad, 2005; Wainwright et al., 2017).

Medical

Infectious diseases were the most commonly addressed medical conditions. Five studies were of veterans who had HIV or hepatitis C and incarceration was examined as a risk factor (Cheung, Hanson, Maganti, Keeffe, & Matsui, 2002; Currie, 2009; Dominitz et al., 2005; Mishra, Sninsky, Roswell, Fitzwilliam, & Hyams, 2003). Mortality while in prison (Luallen & Corry, 2017) and after exiting prison (LePage, Bradshaw, Cipher, Crawford, & Parish-Johnson, 2016) was examined. Other medical conditions examined included brain injury (Virkkunen, Nuutila, & Huusko, 1977), hypertension (Howell et al., 2016) and hormone levels related to antisocial behavior (Mazur, 1995).

Psychosocial

Vocational training was the most commonly studied psychosocial factor in relation to the health of justice-involved veterans. The majority of studies were randomized controlled trials comparing vocational training to usual care among justice-involved veterans in VHA settings (LePage et al., 2016, 2017; LePage, Lewis, Washington, Davis, & Glasgow, 2013; LePage, Ottomanelli, Barnett, & Njoh, 2014; LePage, Washington, Lewis, Johnson, & Garcia-Rea, 2011). Screening for psychosocial issues in primary care was addressed by two studies (Bikson, McGuire, Blue-Howells, & Seldin-Sommer, 2009; Cook, Freedman, Freedman, Arick, & Miller, 1996).

Sample size

Study sample sizes were somewhat evenly distributed with 21% (41/191) of studies with fewer than 100 participants, 40% (77/191) of studies with 100–1000 participants, and 38% (73/191) of studies with over 1000 participants. Of studies with fewer than 100 participants, the majority took place at a single VHA site (13/41; 32%) or at a single court (or multiple courts (9/41; 22%) with additional studies conducted in jail or prison settings or in multiple settings. Of studies with 100–1000 participants, 61% (47/77) were conducted at a single VHA site and 15% (11/77) were conducted in non-VHA settings. Of studies with over 1000 participants, 36% (26/73) used VHA administrative/clinical databases, 22% (16/73) used multiple data sources (e.g., prison release records and VHA administrative databases), and 18% (13/73) collected data from multiple VHA sites. The remaining studies were conducted in prison or jail settings, drew from multiple data sources, or were surveys of veterans.

Research settings

Studies in VHA settings that used administrative databases identified veterans who participated in a VHA justice program (e.g., Finlay et al., 2015; Tsai et al., 2018) or who reported a criminal justice history (Gabrielian et al., 2016; Tejani, Rosenheck, Tsai, Kasprow, & McGuire, 2014). Court mandates for treatment were not recorded in these databases. Single VHA site studies used criminal justice data gathered through randomized controlled trials (Anderson et al., 2017; Bennett et al., 2018), longitudinal treatment surveys (Atkinson, Tolson, & Turner, 1993; Timko et al., 2017), and one-time questionnaires (Backhaus et al., 2016; Briggs et al., 2001). Multiple VHA site studies included qualitative interviews (Blonigen et al., 2018), longitudinal assessments (Tsai, Middleton, et al., 2017), and administrative evaluation data (Coker & Rosenheck, 2014).

Study design

The majority of studies identified for this review used an observational design (173/191; 91%). Ten studies (5%) used a randomized clinical trial design with an additional two studies (1%) conducting secondary analyses of a randomized clinical trial. Six studies (3%) used qualitative interviewing and focus group methods.

Funding source

The majority of studies either did not report a funding source (97/191, 51%) or were unfunded (5/191, 3%). When reported, the most common funding sources were VHA funding (53/191, 28%), National Institutes of Health funding (31/191, 16%), and other government funding (21/191, 11%) including the Department of Defense and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The remaining funding support was from universities (6/191, 3%) and foundations (6/191, 3%).

Discussion

This scoping review summarizes the research literature on justice-involved veterans and their health and healthcare. The majority of studies focused on mental health conditions, and over 90% used an observational research design. Few studies examined medical conditions, psychosocial factors, healthcare delivery and organization, or long-term care and aging in this vulnerable population. Randomized clinical trials aimed at improving health outcomes, rather than simply observing and documenting outcomes, were rare. Half of studies did not report a funding source or were unfunded, 28% of studies were funded by the VHA, and 27% were supported by other government funding.

PTSD, military service, and criminal justice involvement

Mental health conditions, particularly PTSD and substance use disorders, were the foci of most articles published in the justice-involved veterans’ scientific literature. PTSD was consistently linked to more legal problems among US veterans (Backhaus et al., 2016; Black et al., 2005; Saxon et al., 2001). PTSD and combat exposure were significantly associated with violent offending among military veterans in the UK (MacManus et al., 2013). Similarly, among US veterans, PTSD and “anger hyperarousal symptoms” (derived from the Davidson Trauma Scale question that asked in the past week “Have you been irritable or had outbursts of anger?”) were found to predict family violence across a one-year study period (Sullivan & Elbogen, 2014). Among US veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, military sexual trauma was linked with higher predicted probability of legal problems (Backhaus et al., 2016). Prosecutors offered more diversion programs to veterans with PTSD and thought they were less criminally culpable than veterans without PTSD (Wilson, Brodsky, Neal, & Cramer, 2011).

Combat exposure – and related PTSD from such experiences – was examined to explain the link between military experience and criminal justice involvement, though results were mixed. Combat experience has been associated with lower odds of non-violent offending (Bennett et al., 2018), and serving in wartime has been linked with lower odds of incarceration (Culp et al., 2013). However, greater combat exposure has also been associated with higher odds of unlawful behavior, including “having been arrested”, “being on probation or parole”, or “driving a car or other vehicle after having too much to drink” (Larson & Norman, 2014). While neither causal nor conclusive, this body of research on PTSD and combat exposure suggests that systems serving veterans should increase access to evidence-based trauma treatment for justice-involved veterans and develop prevention programs to attenuate their risk for violence and justice involvement.

Other aspects of military service were examined in relation to criminal justice involvement and were similarly inconclusive. Compared to enlisted soldiers, officers had lower odds of being incarcerated (Black et al., 2005) or of violent offending (MacManus et al., 2013). In most studies, period of service was either not specified or included veterans from multiple periods of service without examining differences by service era. One exception was a study that compared veterans from Iraq/Afghanistan, Gulf War, and Vietnam eras: Veterans who served during the Iraq/Afghanistan era had a lower rate of incarceration than veterans from the other eras of service (Fontana & Rosenheck, 2008). Branch of service was mentioned in a few studies. For example, a higher percentage of veterans incarcerated in jail served in the Army or Marines compared to veterans who were not incarcerated (Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2009). Length of service was examined with longer military service associated with fewer lifetime arrests among veterans incarcerated in prison (Brooke & Gau, 2018). However, examination of aspects of military service and links with criminal justice involvement were rare.

Although more research is needed to explore the link between military service and criminal justice involvement, results will have implications for the Department of Defense in their treatment of active duty personnel. For example, if combat trauma is determined to be a mechanism that causes later criminal justice involvement, designing post-deployment treatment programs that comprehensively address PTSD and trauma experienced while personnel are still serving in the military will be an important practice change. The VHA could use the reviewed studies to estimate the number of veterans who may become justice-involved and allocate treatment services to help reduce criminal behavior.

Knowledge gaps and informing policy, practice, and research

The scoping review uncovered numerous gaps in the literature on the health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans. These gaps include studies of different sociodemographic groups, and research on veterans’ medical conditions and the impact of managing multiple medical, mental health, and substance use disorder conditions. Gaps were also apparent for studies of interventions to improve the health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans, especially studies using randomized trials. Differences in health and healthcare by type of criminal justice involvement were understudied. Conceptual models were rarely used to guide studies’ analyses or interpretation of results, and there was little consistency across studies that used conceptual models. The identified gaps provide guidance on areas for future research.

Medical conditions

Needed are studies focused on medical conditions, especially conditions such as traumatic brain injury, which may disproportionately affect veterans and be related to their justice involvement (To et al., 2015). Research on traumatic brain injury in veterans will also be relevant to both veterans and non-veterans with justice involvement as this condition is prevalent among justice-involved populations (Durand et al., 2017). Although hypertension is the most common medical condition among veterans served at the VHA (Frayne et al., 2014), only one study touched on this topic (Howell et al., 2016). Other chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, were unaddressed in the studies we reviewed and need attention in future research. Studies on suicide and suicide risk will inform programming by the VHA Office of Suicide Prevention. Other important topics that need research include mortality, and the impact of civil legal issues on criminal issues and health. For example, studies on medical-legal partnerships (Tsai, Middleton, et al., 2017) may shed light on the types of civil legal issues that are most effectively addressed among veterans, allowing legal providers to be strategic with their time and resources.

Management of multiple conditions

Even though chronic mental health or addiction conditions, including depression and alcohol use disorder, were examined in a number of studies, the long-term management of these conditions in clinical practice among justice-involved veterans is an area of untapped investigation. A subset of studies examined multiple medical, mental health, and substance use disorder conditions, however, most lacked in-depth analysis on the topic, only reporting the prevalence of such conditions and health services utilization. Some studies examined the interaction of these conditions. However, given that 35–58% of justice-involved veterans served by VHA outreach programs have co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (Finlay et al., 2017; Finlay, Smelson, et al., 2016) and many have medical conditions (Brown & Jones, 2015), more studies are needed that examine the cumulative effect of managing multiple conditions to inform clinical practice and policy. Studies that investigate how cycling in and out of incarceration impacts management of multiple conditions are also important. Furthermore, many justice-involved veterans who have mental health and addiction conditions struggle with homelessness and unemployment. Although the VHA and community programs provide comprehensive housing and employment training services to some justice-involved veterans, the impact of these programs, especially for veterans with multiple chronic mental health and addiction conditions, is unknown. Efforts to identify and evaluate approaches to meeting housing and employment needs across the spectrum of justice-involved veterans will be critical to improving the health of this population by means of improved clinical practice and evolving policy decisions.

Sociodemographic differences

The scoping review highlights that we need to know more about sociodemographic groups within the justice-involved veteran population, such as women, people of color, rural veterans, veterans with disabilities, and veterans from different periods of service and service branches. Only a few studies examined women veterans separately from men (Finlay et al., 2015; Stainbrook et al., 2016) and only one study was of transgender compared to non-transgender veterans (Brown & Jones, 2015). To inform clinical practice and policy, research is needed to examine the extent to which these underrepresented veterans differ from white male veterans living in urban areas, who have predominated in most justice-related studies, what unique programmatic needs they may have, and the effectiveness of tailored intervention programs.

Intervention studies

Along with studies on sociodemographic groups, intervention studies focused on addressing the unique and additional treatment needs of justice-involved veterans and preventing or reducing their criminal justice involvement are needed. There is a robust literature examining the link between criminal justice involvement and mental health and addiction issues (e.g., Baillargeon, Binswanger, Penn, Williams, & Murray, 2009; Binswanger et al., 2012), and the effectiveness of interventions to improve outcomes among the general population of justice-involved individuals (e.g., Cusack, Morrissey, Cuddeback, Prins, & Williams, 2010; Kinlock et al., 2007). Borrowing from this literature to inform policy and practice with veterans, as well as developing this body of research among veterans will help move the field of justice-involved veterans research forward. Expanding the study designs used to include more randomized controlled trials, qualitative studies such as interviews or focus groups, and more rigorous observational studies that allow for propensity score analysis and other sophisticated statistical tests are needed.

Although 30% of studies focused on veterans in non-VHA settings, information on the quality of health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans in non-VHA treatment setting is lacking, as is best practices for how to coordinate between VHA and non-VHA treatment settings. The lack of studies in non-VHA settings may be partially because most healthcare provided to veterans occurred at VHA facilities. However, in 2014, Congress enacted the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act, known as the Veterans Choice Program, which enabled the VHA to substantially expand the purchase of community care for veterans. Primary care and mental health care, including substance use disorder care, were among the top five types of community care used by veterans (Vanneman et al., 2017). In 2018, the VA MISSION Act continued funding for the Veterans Choice Program and an additional 640,000 veterans are estimated to move into community care annually in the early years of the program (Rieselbach, Epperly, Nycz, & Shin, 2019). Understanding what impact purchased care has on justice-involved veterans and coordination between VHA and non-VHA treatment is important to ensuring they are receiving high quality care (Liu et al., 2010).

Type of criminal justice involvement

Distinctions in the health and healthcare among veterans involved in different aspects of the criminal justice system are difficult to draw because the majority of articles did not examine differences by criminal justice type. Most articles asked about current (Backhaus et al., 2016; Cook et al., 1996) or past criminal justice involvement, such as lifetime legal problems measured by the Addiction Severity Index (Anderson et al., 2017; Benda et al., 2003a; Bennett et al., 2018; Cacciola, Rutherford, Alterman, & Snider, 1994), and results were not reported by type of criminal justice involvement. Studies also examined veterans in jail diversion programs (Clark, Barrett, Frei, & Christy, 2016; Hartwell et al., 2014), courts (Clifford, Fischer, & Pelletier, 2014; Gallagher, Nordberg, & Gallagher, 2016; Hoyt et al., 2014), or jails (Davis, Baer, Saxon, & Kivlahan, 2003; Greenberg & Rosenheck, 2009; Saxon et al., 2001), but these studies often lacked comparison groups.

There were several articles that studied veterans incarcerated in prison, but samples were limited to US state prisons only with no comparisons with US federal prisons (Boivin, 1987; Brooke & Gau, 2018; Luallen & Corry, 2017; Stacer & Solinas-Saunders, 2015; Tsai & Goggin, 2017) or it was not stated where the incarceration occurred (Black et al., 2005). One exception was a study found that a higher percentage of jail incarcerated veterans had current indicators of mental health problems and more previous mental health problems than prison incarcerated veterans (Bronson et al., 2015). From the broader criminal justice literature, limited evidence suggests that individuals incarcerated in prisons have similar or greater medical needs (Maruschak, Berzofsky, & Unangst, 2015), but have fewer mental health needs compared to individuals in jails (Bronson & Berzofsky, 2017). Individuals in prison also may have greater access to healthcare than those in jails or under community supervision, including medical care (Maruschak et al., 2015) and substance use treatment (Taxman, Perdoni, & Harrison, 2007), which likely is related to being in a confined environment for longer sentences. However, given that the majority of justice-involved individuals are under community supervision (71%) (Kaeble, Glaze, Tsoutis, & Minton, 2016), future work should identify and better understand potential differences in health and healthcare by criminal justice status.

Conceptual models

Although the majority of studies in our scoping review lacked a conceptual model, a few studies drew from conceptual models across a variety of fields. One study grounded their research in criminology models, including the importation model and the functionalist model (Stacer & Solinas-Saunders, 2015). Conceptual models drawn from psychology included psychosocial rehabilitation (Elbogen, Johnson, Wagner, et al., 2012), ecological theory and cross-cultural approaches (Clifford et al., 2014), and a survivor mode coping model (Wilson & Zigelbaum, 1983). Two health services studies used the Gelberg-Andersen Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gabrielian et al., 2016; Petrovich et al., 2014). Finally, the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) model was used in an implementation science study (Blonigen et al., 2018). The field of justice-involved veterans draws from different disciplines with their own conceptual models, but the lack of a common framework is a notable gap. Convening an interdisciplinary research consortium to develop a unifying conceptual model will help integrate these disciplines and guide future research.

Limitations of the scoping review

This scoping review was designed to provide a broad overview of the literature on the health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans and how these articles add to our general understanding of criminal justice involved populations. We did not provide an in-depth analysis of the topics covered in the reviewed studies, the quality of these studies, or an investigation of bias; thus, we were limited in the conclusions we could draw about the research we reviewed. We did not conduct a second review of all full-text articles; rather, a second review was conducted on only a subset of articles. Finally, we limited our search to healthcare databases. Additional articles relevant to our review may have been published in other fields, such as law journals, and not every relevant article may have been identified using our search strategy. Articles not available in English that may have been relevant were also excluded due to limitations on the availability of translation. However, the search strategy used likely identified most key studies available in English and the findings likely reflect the scope of healthcare issues related to justice-involved veterans currently in the literature. Many of the articles we excluded focused on legal aspects of veterans’ experiences in the criminal justice system, such as recidivism and legal rationales for considering PTSD when charging a veteran. Criminal justice outcomes were included in some of the studies in our scoping review, though we did not summarize those outcomes here. We instead focused our review on health and healthcare outcomes, but a more comprehensive review of the literature including health, law, and other related areas, such as sociology, may be needed to fully understand the experiences of justice-involved veterans.

Conclusions

Identifying and organizing existing literature to inform current research, and strategically expanding into existing gaps, will help to generate a robust body of literature focused on the health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans. The current review identified gaps in the justice-involved veteran literature, which also may exist in the general literature on justice-involved individuals, and highlighted areas for future research. Accomplishment of research in the identified domains will help inform policy and practice to improve the health and healthcare of justice-involved veterans as well as treatment for other justice-involved populations who have similar experiences of trauma and mental health and addiction issues.

Abbreviations

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- VHA:

-

Veterans Health Administration

References

Anderson, R. E., Bonar, E. E., Walton, M. A., Goldstick, J. E., Rauch, S. A. M., Epstein-Ngo, Q. M., & Chermack, S. T. (2017). A latent profile analysis of aggression and victimization across relationship types among veterans who use substances. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(4), 597–607.

Arskey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Atkinson, R. M., Tolson, R. L., & Turner, J. A. (1993). Factors affecting outpatient treatment compliance of older male problem drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 54(1), 102–106.

Backhaus, A., Gholizadeh, S., Godfrey, K. M., Pittman, J., & Afari, N. (2016). The many wounds of war: The association of service-related and clinical characteristics with problems with the law in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 49, 205–213.

Baillargeon, J., Binswanger, I. A., Penn, J. V., Williams, B. A., & Murray, O. J. (2009). Psychiatric disorders and repeat incarcerations: The revolving prison door. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(1), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030416.

Bale, R. N., Van Stone, W. W., Kuldau, J. M., Engelsing, T. M., Elashoff, R. M., & Zarcone, V. P., Jr. (1980). Therapeutic communities vs methadone maintenance. A prospective controlled study of narcotic addiction treatment: Design and one-year follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 37(2), 179–193.

Bale, R. N., Zarcone, V. P., Van Stone, W. W., Kuldau, J. M., Engelsing, T. M., & Elashoff, R. M. (1984). Three therapeutic communities. A prospective controlled study of narcotic addiction treatment: Process and two-year follow-up results. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41(2), 185–191.

Beckerman, A., & Fontana, L. (1989). Vietnam veterans and the criminal justice system: A selected review. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 16(4), 412–428.

Benda, B. B., Rodell, D. E., & Rodell, L. (2003a). Crime among homeless military veterans who abuse substances. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 26(4), 332–345.

Benda, B. B., Rodell, D. E., & Rodell, L. (2003b). Differentiating nuisance from felony offenses among homeless substance abusers in a V.A. medical center. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 37(1), 41–65.

Benda, B. B., Rodell, D. E., & Rodell, L. (2003c). Homeless alcohol/other drug abusers: Discriminators of non-offenders, nuisance offenders, and felony offenders. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 21(3), 59–80.

Bennett, D. C., Morris, D. H., Sexton, M. B., Bonar, E. E., & Chermack, S. T. (2018). Associations between posttraumatic stress and legal charges among substance using veterans. Law and Human Behavior, 42(2), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000268.

Bikson, K., McGuire, J., Blue-Howells, J., & Seldin-Sommer, L. (2009). Psychosocial problems in primary care: Patient and provider perceptions. Social Work in Health Care, 48(8), 736–749.

Binswanger, I. A., Merrill, J. O., Krueger, P. M., White, M. C., Booth, R. E., & Elmore, J. G. (2010). Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149591.

Binswanger, I. A., Nowels, C., Corsi, K. F., Glanz, J., Long, J., Booth, R. E., & Steiner, J. F. (2012). Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: A qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1940-0640-7-3.

Black, D. W., Carney, C. P., Peloso, P. M., Woolson, R. F., Letuchy, E., & Doebbeling, B. N. (2005). Incarceration and veterans of the first gulf war. Military Medicine, 170(7), 612–618.

Blodgett, J. C., Avoundjian, T., Finlay, A. K., Rosenthal, J., Asch, S. M., Maisel, N. C., & Midboe, A. M. (2015). Prevalence of mental health disorders among justice-involved veterans. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxu003.

Blonigen, D. M., Bui, L., Elbogen, E., Blodgett, J. C., Maisel, N. C., Midboe, A. M., et al. (2016). Risk of recidivism among justice-involved veterans: A systematic review of the literature. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(8), 812–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403414562602.

Blonigen, D. M., Rodriguez, A. L., Manfredi, L., Nevedal, A., Rosenthal, J., McGuire, J. F., et al. (2018). Cognitive-behavioral treatments for criminogenic thinking: Barriers and facilitators to implementation within the veterans health administration. Psychological Services, 15(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000128.

Boivin, M. J. (1987). Forgotten warriors: An evaluation of the emotional well-being of presently incarcerated Vietnam veterans. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 113(1), 109–125.

Bray, I., O'Malley, P., Ashcroft, S., Adedeji, L., & Spriggs, A. (2013). Ex-military personnel in the criminal justice system: A cross-sectional study. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 52(5), 516–526.

Briggs, M. E., Baker, C., Hall, R., Gaziano, J. M., Gagnon, D., Bzowej, N., & Wright, T. L. (2001). Prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection at an urban veterans administration medical center. Hepatology, 34(6), 1200–1205.

Bromley, E., Mikesell, L., Whelan, F., Hellemann, G., Hunt, M., Cuddeback, G., et al. (2017). Clinical factors associated with successful discharge from assertive community treatment. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(8), 916–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0083-1.

Bronson, J., & Berzofsky, M. (2017). Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12 (NCJ 250612). Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf

Bronson, J., Carson, E. A., Noonan, M., & Berzofsky, M. (2015). Veterans in prison and jail, 2011–12 (NCJ 249144). Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vpj1112.pdf

Brooke, E. J., & Gau, J. M. (2018). Military service and lifetime arrests examining the effects of the total military experience on arrests in a sample of prison inmates. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 29(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403415619007.

Brown, G. R., & Jones, K. T. (2015). Health correlates of criminal justice involvement in 4,793 transgender veterans. LGBT Health, 2(4), 297–305.

Brown, G. R., & Jones, K. T. (2016). Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the veterans health administration: A case-control study. LGBT Health, 3(2), 122–131.

Brown, W. B. (2011). From war zones to jail: Veteran reintegration problems. Justice Policy Journal, 8, 1–48.

Brown, W. B., Stanulis, R., Theis, B., Farnsworth, J., & Daniels, D. (2013). The perfect storm: Veterans, culture and the criminal justice system. Justice Policy Journal, 10(2), 1–44.

Butt, A. A., Wagener, M., Shakil, A. O., & Ahmad, J. (2005). Reasons for non-treatment of hepatitis C in veterans in care. Journal of Viral Hepatitis, 12(1), 81–85.

Cacciola, J. S., Alterman, A. I., Rutherford, M. J., McKay, J. R., & McLellan, A. T. (1998). The early course of change in methadone maintenance. Addiction, 93(1), 41–49.

Cacciola, J. S., Rutherford, M. J., Alterman, A. I., & Snider, E. C. (1994). An examination of the diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality disorder in substance abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 182(9), 517–523.

Calsyn, D. A., Roszell, D. K., & Chaney, E. F. (1989). Validation of MMPI profile subtypes among opioid addicts who are beginning methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(6), 991–998.

Canada, K. E., & Albright, D. L. (2014). Veterans in the criminal justice system and the role of social work. Journal of Forensic Social Work, 4, 48–62.

Cantrell, B. C. (1999). Social support as a function of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within Washington state Vietnam veteran populations. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 60(8), 4207.

Cheung, R. C., Hanson, A. K., Maganti, K., Keeffe, E. B., & Matsui, S. M. (2002). Viral hepatitis and other infectious diseases in a homeless population. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 34(4), 476–480.

Clark, C., Barrett, B., Frei, A., & Christy, A. (2016). What makes a peer a peer? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(1), 74–76.

Clark, S., Blue-Howells, J., & McGuire, J. (2014). What can family courts learn from the veterans treatment courts? Family Court Review, 52(3), 417–424.

Clifford, P., Fischer, R. L., & Pelletier, N. (2014). Exploring veteran disconnection: Using culturally responsive methods in the evaluation of veterans treatment court services. Military Behavioral Health, 2, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2014.904716.

Coker, K. L., & Rosenheck, R. (2014). Race and incarceration in an aging cohort of Vietnam veterans in treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The Psychiatric Quarterly, 85(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-013-9272-4.

Comings, D. E., Muhleman, D., Ahn, C., Gysin, R., & Flanagan, S. D. (1994). The dopamine D2 receptor gene: A genetic risk factor in substance abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 34(3), 175–180.

Cook, C. A., Freedman, J. A., Freedman, L. D., Arick, R. K., & Miller, M. E. (1996). Screening for social and environmental problems in a VA primary care setting. Health & Social Work, 21(1), 41–47.

Copeland, L. A., Miller, A. L., Welsh, D. E., McCarthy, J. F., Zeber, J. E., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2009). Clinical and demographic factors associated with homelessness and incarceration among VA patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Public Health, 99(5), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149989.

Cote, I. (2013). Pilot project on incarcerated former military personnel in three Ontario detention centres, 2011-2012. In A. B. Aiken, & Bélanger, S. A. H. (Eds.), Beyond the Line: Military and Veteran Health Research (pp. 307–318). Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Craig, R. J. (1980). Characteristics of inner city heroin addicts applying for treatment in a veteran administration hospital drug program (Chicago). International Journal of the Addictions, 15(3), 409–418.

Culp, R., Youstin, T. J., Englander, K., & Lynch, J. (2013). From war to prison: Examining the relationship between military service and criminal activity. Justice Quarterly, 30(4), 651–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.615755.

Currie, S. (2009). An investigation of the quantity and type of female veterans’ responses to hepatitis C treatment screening and acceptance. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 70(2), 487.

Cusack, K. J., Morrissey, J. P., Cuddeback, G. S., Prins, A., & Williams, D. M. (2010). Criminal justice involvement, behavioral health service use, and costs of forensic assertive community treatment: A randomized trial. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(4), 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9299-z.

Cusack, M., & Montgomery, A. E. (2017). Examining the bidirectional association between veteran homelessness and incarceration within the context of permanent supportive housing. Psychological Services, 14(2), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000110.

Danan, E. R., Krebs, E. E., Ensrud, K., Koeller, E., MacDonald, R., Velasquez, T., et al. (2017). An evidence map of the women veterans’ health research literature (2008-2015). Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(12), 1359–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4152-5.

Davis, A. K., Bonar, E. E., Goldstick, J. E., Walton, M. A., Winters, J., & Chermack, S. T. (2017). Binge-drinking and non-partner aggression are associated with gambling among veterans with recent substance use in VA outpatient treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 27–32.

Davis, T. M., Baer, J. S., Saxon, A. J., & Kivlahan, D. R. (2003). Brief motivational feedback improves post-incarceration treatment contact among veterans with substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69, 197–203.

Decker, K. P., Peglow, S. L., & Samples, C. R. (2014). Participation in a novel treatment component during residential substance use treatment is associated with improved outcome: A pilot study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 9, 7.

Derkzen, D., & Wardop, K. (2015). A profile of veterans within the correctional service of Canada. Retrieved from Correctional Service, Government of Canada website: http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/005008-rb-15-09-eng.shtml

DeViva, J. C. (2014). Treatment utilization among OEF/OIF veterans referred for psychotherapy for PTSD. Psychological Services, 11(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035077.

Dominitz, J. A., Boyko, E. J., Koepsell, T. D., Heagerty, P. J., Maynard, C., Sporleder, J. L., et al. (2005). Elevated prevalence of hepatitis C infection in users of United States veterans medical centers. Hepatology, 41(1), 88–96.

Donley, S., Habib, L., Jovanovic, T., Kamkwalala, A., Evces, M., Egan, G., et al. (2012). Civilian PTSD symptoms and risk for involvement in the criminal justice system. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, 40(4), 522–529.

Douyon, R., Guzman, P., Romain, G., Ireland, S. J., Mendoza, L., Lopez-Blanco, M., & Milanes, F. (1998). Subtle neurological deficits and psychopathological findings in substance-abusing homeless and non-homeless veterans. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 10(2), 210–215.

Durand, E., Chevignard, M., Ruet, A., Dereix, A., Jourdan, C., & Pradat-Diehl, P. (2017). History of traumatic brain injury in prison populations: A systematic review. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 60(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2017.02.003.

Edalati, H., & Nicholls, T. L. (2017). Childhood maltreatment and the risk for criminal justice involvement and victimization among homeless individuals: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017708783.

Elbogen, E. B., Johnson, S. C., Newton, V. M., Straits-Troster, K., Vasterling, J. J., Wagner, H. R., & Beckham, J. C. (2012). Criminal justice involvement, trauma, and negative affect in Iraq and Afghanistan war era veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1097–1102.

Elbogen, E. B., Johnson, S. C., Wagner, H. R., Newton, V. M., Timko, C., Vasterling, J. J., & Beckham, J. C. (2012). Protective factors and risk modification of violence in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(6), e767–e773.

Elbogen, E. B., Sullivan, C. P., Wolfe, J., Wagner, H. R., & Beckham, J. C. (2013). Homelessness and money mismanagement in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. American Journal of Public Health, 103(Suppl 2), S248–S254. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301335.

Erickson, S. K., Rosenheck, R. A., Trestman, R. L., Ford, J. D., & Desai, R. A. (2008). Risk of incarceration between cohorts of veterans with and without mental illness discharged from inpatient units. Psychiatric Services, 59(2), 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.59.2.178.

Fine, E. W., & Levin, L. D. (2008). Posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans: Clinical and legal perspectives. American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 29(2), 5–17.

Finlay, A. K., Binswanger, I., Timko, C., Rosenthal, J., Clark, S., Blue-Howells, J., et al. (2018). Receipt of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder by male justice-involved U.S. veterans health administration patients. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 29(9), 875–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403416644011.

Finlay, A. K., Binswanger, I. A., Smelson, D., Sawh, L., McGuire, J., Rosenthal, J., et al. (2015). Sex differences in mental health and substance use disorders and treatment entry among justice-involved veterans in the veterans health administration. Medical Care, 53(Suppl 1), S105–S111. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000271.

Finlay, A. K., Harris, A. H., Rosenthal, J., Blue-Howells, J., Clark, S., McGuire, J., et al. (2016). Receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder by justice-involved U.S. veterans health administration patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 222–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.013.

Finlay, A. K., Smelson, D., Sawh, L., McGuire, J., Rosenthal, J., Blue-Howells, J., et al. (2016). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs veterans justice outreach program: Connecting justice-involved veterans with mental health and substance use disorder treatment. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(2), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403414562601.

Finlay, A. K., Stimmel, M., Blue-Howells, J., Rosenthal, J., McGuire, J., Binswanger, I., et al. (2017). Use of veterans health administration mental health and substance use disorder treatment after exiting prison: The health care for reentry veterans program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0708-z.

Fontana, A., & Rosenheck, R. (2008). Treatment-seeking veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan: Comparison with veterans of previous wars. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(7), 513–521.

Frayne, S., Phibbs, C., Saechao, F., Maisel, N., Friedman, S., Finlay, A. K., et al. (2014). Sourcebook: Women veterans in the veterans health administration. Volume 3. Sociodemographics, utilization, costs of care, and health profile. Washington DC: Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Gabrielian, S., Burns, A. V., Nanda, N., Hellemann, G., Kane, V., & Young, A. S. (2016). Factors associated with premature exits from supported housing. Psychiatric Services, 67(1), 86–93.

Gallagher, J. R., Nordberg, A., & Gallagher, J. M. (2017). A qualitative investigation into military veterans’ experiences in a problem-solving court: Factors that impact graduation rates. Social Work in Mental Health, 15(5), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2016.1237925.

Gauthier, J. R., (2017). Moral injury and the justice-involved veteran. University of California, Santa Barbara: Retrieved from https://www.alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f38c9wdm.

Gerlock, A. A. (1999). Comparison and prediction of completers and non-completers of a domestic violence program. University of Washington Retrieved from https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/7295.

Gerlock, A. A. (2004). Domestic violence and post-traumatic stress disorder severity for participants of a domestic violence rehabilitation program. Military Medicine, 169(6), 470–474.

Greenberg, G. A., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2009). Mental health and other risk factors for jail incarceration among male veterans. Psychiatric Quarterly, 80(1), 41–53.

Greenberg, G. A., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2012). Incarceration among male veterans: Relative risk of imprisonment and differences between veteran and nonveteran inmates. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56(4), 646–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X11406091.

Greenberg, G. A., Rosenheck, R. A., & Desai, R. A. (2007). Risk of incarceration among male veterans and nonveterans: Are veterans of the all volunteer force at greater risk? Armed Forces and Society, 33(3), 337–350.

Groppenbacher, J., Batzer, G. B., & White, L. (2003). Reducing hospitalizations and arrests for substance abusers. The American Journal on Addictions, 12(2), 153–158.

Hamilton, A. B., Poza, I., & Washington, D. L. (2011). “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: Pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Womens Health Issues, 21(4 Suppl), S203–S209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.04.005.

Harmless, A. (1990). Developmental impact of combat exposure: Comparison of adolescent and adult Vietnam veterans. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 60(2), 185–195.

Harpaz-Rotem, I., Rosenheck, R. A., & Desai, R. (2006). The mental health of children exposed to maternal mental illness and homelessness. Community Mental Health Journal, 42(5), 437–448.

Hartwell, S. W., James, A., Chen, J., Pinals, D. A., Marin, M. C., & Smelson, D. (2014). Trauma among justice-involved veterans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(6), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037725.

Heinz, A. J., Cohen, N. L., Holleran, L., Alvarez, J. A., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2016). Firearm ownership among military veterans with PTSD: A profile of demographic and psychosocial correlates. Military Medicine, 181(10), 1207–1211.

Hiley-Young, B., Blake, D. D., Abueg, F. R., Rozynko, V., & Gusman, F. D. (1995). Warzone violence in Vietnam: An examination of premilitary, military, and postmilitary factors in PTSD in-patients. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 125–141.

Holbrook, J. G., & Anderson, S. (2011). Veterans courts: Early outcomes and key indicators for success. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1912655

Howell, B. A., Long, J. B., Edelman, E. J., McGinnis, K. A., Rimland, D., Fiellin, D. A., et al. (2016). Incarceration history and uncontrolled blood pressure in a multi-site cohort. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(12), 1496–1502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3857-1.

Hoyt, T., Wray, A. M., & Rielage, J. K. (2014). Preliminary investigation of the roles of military background and posttraumatic stress symptoms in frequency and recidivism of intimate partner violence perpetration among court-referred men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(6), 1094–1110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513506058.

Hser, Y. I., Stark, M. E., Paredes, A., Huang, D., Anglin, M. D., & Rawson, R. (2006). A 12-year follow-up of a treated cocaine-dependent sample. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(3), 219–226.

Ilgen, M. A., Harris, A. H., Moos, R. H., & Tiet, Q. Q. (2007). Predictors of a suicide attempt one year after entry into substance use disorder treatment. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(4), 635–642.

Joe, G. W., & Hudiburg, R. A. (1978). Behavioral correlates of age at first marijuana use. International Journal of the Addictions, 13(4), 627–637.

Johnson, D. R., Rosenheck, R., Fontana, A., Lubin, H., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (1996). Outcome of intensive inpatient treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(6), 771–777.

Johnson, R. S., Graham, D. P., Sikes, K., Nelsen, A., & Stolar, A. (2015). An analysis of sanctions and respective psychiatric diagnoses in veterans’ court. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, 43(2), 171–176.

Johnson, R. S., Stolar, A. G., McGuire, J. F., Mittakanti, K., Clark, S., Coonan, L. A., & Graham, D. P. (2017). Predictors of incarceration of veterans participating in U.S. veterans’ courts. Psychiatric Services, 68(2), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500266.

Johnson, R. S., Stolar, A. G., Wu, E., Coonan, L. A., & Graham, D. P. (2015). An analysis of successful outcomes and associated contributing factors in veterans’ court. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 79(2), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.2015.79.2.166.

Kaeble, D., Glaze, L., Tsoutis, A., & Minton, T. (2016). Correctional populations in the United States, 2014 (NCJ 249513). Retrieved from U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus14.pdf

Kasarabada, N. D., Anglin, M. D., Stark, E., & Paredes, A. (2000). Cocaine, crime, family history of deviance-are psychosocial correlates related to these phenomena in male cocaine abusers? Substance Abuse, 21(2), 67–78.

Kashner, T., Rosenheck, R., Campinell, A. B., Suris, A., Crandall, R., Garfield, N. J., et al. (2002). Impact of work therapy on health status among homeless, substance-dependent veterans: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 938–945.

Katon, J. G., Lehavot, K., Simpson, T. L., Williams, E. C., Barnett, S. B., Grossbard, J. R., et al. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences, military service, and adult health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(4), 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.020.

Khalsa, H. K., Kowalewski, M. R., Anglin, M. D., & Wang, J. (1992). HIV-related risk behaviors among cocaine users. AIDS Education and Prevention, 4(1), 71–83.

Kimbrel, N. A., Calhoun, P. S., Elbogen, E. B., Brancu, M., Beckham, J. C., Green, K. T., et al. (2014). The factor structure of psychiatric comorbidity among Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans and its relationship to violence, incarceration, suicide attempts, and suicidality. Psychiatry Research, 220(1), 397–403.

Kinlock, T. W., Gordon, M. S., Schwartz, R. P., O'Grady, K., Fitzgerald, T. T., & Wilson, M. (2007). A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 1-month post-release. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 91(2–3), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.022.

Knudsen, K. J., & Wingenfeld, S. (2016). A specialized treatment court for veterans with trauma exposure: Implications for the field. Community Mental Health Journal, 52, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9845-9.

Kopera-Frye, K., Harrison, M. T., Iribarne, J., Dampsey, E., Adams, M., Grabreck, T., et al. (2013). Veterans aging in place behind bars: A structured living program that works. Psychological Services, 10(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031269.

Larson, G. E., & Norman, S. B. (2014). Prospective prediction of functional difficulties among recently separated veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(3), 415–428.

Laudet, A., Timko, C., & Hill, T. (2014). Comparing life experiences in active addiction and recovery between veterans and non-veterans: A national study. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 33(2), 148–162.

LePage, J. P., Bradshaw, L. D., Cipher, D. J., Crawford, A. M., & Parish-Johnson, J. A. (2016). The association between recent incarceration and inpatient resource use and death rates: Evaluation of a US veteran sample. Public Health, 134, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.01.009.

LePage, J. P., Lewis, A. A., Crawford, A. M., Parish, J. A., Ottomanelli, L., Washington, E. L., & Cipher, D. J. (2016). Incorporating individualized placement and support principles into vocational rehabilitation for formerly incarcerated veterans. Psychiatric Services, 67(7), 735–742.

LePage, J. P., Lewis, A. A., Crawford, A. M., Washington, E. L., Parish-Johnson, J. A., Cipher, D. J., & Bradshaw, L. D. (2017). Vocational rehabilitation for veterans with felony histories and mental illness: 12-month outcomes. Psychological Services, 15(1), 56–64.

LePage, J. P., Lewis, A. A., Washington, E. L., Davis, B., & Glasgow, A. (2013). Effects of structured vocational services in ex-offender veterans with mental illness: 6-month follow-up. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 50(2), 183–192.

LePage, J. P., Ottomanelli, L., Barnett, S. D., & Njoh, E. N. (2014). Spinal cord injury combined with felony history: Effect on supported employment for veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 51(10), 1497–1504.

LePage, J. P., Washington, E. L., Lewis, A. A., Johnson, K. E., & Garcia-Rea, E. A. (2011). Effects of structured vocational services on job-search success in ex-offender veterans with mental illness: 3-month follow-up. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 48(3), 277–286.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339, b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Liu, C. F., Chapko, M., Bryson, C. L., Burgess, J. F., Jr., Fortney, J. C., Perkins, M., et al. (2010). Use of outpatient care in veterans health administration and Medicare among veterans receiving primary care in community-based and hospital outpatient clinics. Health Services Research, 45(5 Pt 1), 1268–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01123.x.

Luallen, J., & Corry, N. (2017). On the prevalence of veteran deaths in state prisons. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 28(4), 394–411.

Lynch, D. M., & Noel, H. C. (2010). Integrating DSM-IV factors to predict violence in high-risk psychiatric patients. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 55(1), 121–128.

MacManus, D., Dean, K., Jones, M., Rona, R. J., Greenberg, N., Hull, L., et al. (2013). Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: A data linkage cohort study. Lancet, 381(9870), 907–917.

Mallik-Kane, K., & Visher, C. A. (2008). Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Retrieved from the Urban Institute website: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411617_health_prisoner_reentry.pdf.

Marciniak, R. D. (1986). Implications to forensic psychiatry of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review. Military Medicine, 151(8), 434–437.

Maruschak, L. M., Berzofsky, M., & Unangst, J. (2015). Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Retrieved from Bureau of Justice: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf

Mays, D. M., Gordon, A. J., Kelly, M. E., & Forman, S. D. (2006). Violent criminal behavior and perspectives on treatment of criminality in opiate treatment. Substance Abuse, 26(2), 33–42.

Mazur, A. (1995). Biosocial models of deviant behavior among male army veterans. Biological Psychology, 41(3), 271–293.

McDonough, D. E., Blodgett, J. C., Midboe, A. M., & Blonigen, D. M. (2015). Justice-involved veterans and employment: A systematic review of barriers and promising strategies and interventions. Menlo Park: Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System.

McGuire, J. (2008). The incarcerated veterans transition program (IVTP): A pilot program evaluation of IVTP employment and enrollment, VA service use and criminal recidivism. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Report to Congress.

McGuire, J., Rosenheck, R. A., & Kasprow, W. J. (2003). Health status, service use, and costs among veterans receiving outreach services in jail or community settings. Psychiatric Services, 54(2), 201–207.

McKay, J. R., McLellan, A. T., Alterman, A. I., Cacciola, J. S., Rutherford, M. J., & O'Brien, C. P. (1998). Predictors of participation in aftercare sessions and self-help groups following completion of intensive outpatient treatment for substance abuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 59(2), 152–162.

McKay, J. R., Merikle, E., Mulvaney, F. D., Weiss, R. V., & Koppenhaver, J. M. (2001). Factors accounting for cocaine use two years following initiation of continuing care. Addiction, 96(2), 213–225.

McLellan, A. T., Ball, J. C., Rosen, L., & O'Brien, C. P. (1981). Pretreatment source of income and response to methadone maintenance: A follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138(6), 785–789.

McLellan, A. T., Erdlen, F. R., Erdlen, D. L., & O'Brien, C. P. (1981). Psychological severity and response to alcoholism rehabilitation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 8(1), 23–35.

McLellan, A. T., Luborsky, L., O'Brien, C. P., Barr, H. L., & Evans, F. (1986). Alcohol and drug abuse treatment in three different populations: Is there improvement and is it predictable? The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 12(1), 101–120.

McLellan, A. T., Luborsky, L., O'Brien, C. P., Woody, G. E., & Druley, K. A. (1982). Is treatment for substance abuse effective? JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 247(10), 1423–1428.

McQuaid, J. R., Brown, S., Aarons, G. A., Smith, T. L., Patterson, T. L., & Schuckit, M. A. (2000). Correlates of life stress in an alcohol treatment sample. Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 131–137.

Mishra, G., Sninsky, C., Roswell, R., Fitzwilliam, S., & Hyams, K. C. (2003). Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among patients receiving health care in a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 48(4), 815–820.

Mohamed, S. (2013). Dual diagnosis among intensive case management participants in the veterans health administration: Correlates and outcomes. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 9(4), 311–321.

Montgomery, A. E., Szymkowiak, D., Marcus, J., Howard, P., & Culhane, D. P. (2016). Homelessness, unsheltered status, and risk factors for mortality: Findings from the 100 000 homes campaign. Public Health Reports, 131(6), 765–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354916667501.

Moore, D. T., Fuehrlein, B. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2017). Delirium tremens and alcohol withdrawal nationally in the veterans health administration. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(7), 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12603.

Mumola, C. J. (2000). Veterans in prison or jail (NCJ 178888). Retrieved from U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs website: https://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vpj.pdf.

Nace, E. P., Meyers, A. L., O'Brien, C. P., Ream, N., & Mintz, J. (1977). Depression in veterans two years after Viet Nam. American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(2), 167–170.

Neale, M. S., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2000). Therapeutic limit setting in an assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services, 51(4), 499–505.

Noonan, M. E., & Mumola, C. J. (2007). Veterans in state and federal prison, 2004 (NCJ 217199). Retrieved from Bureau of Justice Statistics website: http://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/vsfp04.pdf

Otis, G. D., & Louks, J. L. (2001). Differentiation of psychopathology by psychological type. Journal of Psychological Type, 57, 5–17.

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan — A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Pandiani, J. A., Ochs, W. R., & Pomerantz, A. S. (2010). Criminal justice involvement of armed forces veterans in two systems of care. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 835–837.

Pandiani, J. A., Rosenheck, R., & Banks, S. M. (2003). Elevated risk of arrest for veteran’s administration behavioral health service recipients in four Florida counties. Law and Human Behavior, 27(3), 289–298.

Peralme, L. (1995). Predictors of post-combat violent behavior in Vietnam veterans. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 56(12), 7053.

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal for Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

Petrovich, J. C., Pollio, D. E., & North, C. S. (2014). Characteristics and service use of homeless veterans and nonveterans residing in a low-demand emergency shelter. Psychiatric Services, 65(6), 751–757. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300104.