Abstract

Background

Schizophrenia shares some genetic risk and clinical symptoms with bipolar disorder. Clinical heterogeneity across subjects is thought to contribute to variable structural imaging findings across studies. The current study investigates cortical thickness in young adults diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder with a history of hyperthymic mania. We hypothesize that cortical thickness will be most similar between SCZ and the psychotic bipolar 1 disorder subtype.

Methods

Patients with schizophrenia (n = 52), psychotic bipolar I disorder (PBD; n = 49) and non-psychotic bipolar I disorder (NPBD; n = 24) and healthy controls (n = 40) were scanned in a 3T Trio MRI. The thickness of 34 cortical regions was estimated with FreeSurfer, and analyzed using univariate analyses of variance. Relationships to psychotic (SAPS) and negative (SANS) symptoms were investigated using linear regression.

Results

Cortical thickness showed significant group effects, after covarying for sex, age, and intracranial volume (p = 0.001). SCZ subjects had thinner paracentral, inferior parietal, supramarginal and fusiform cortices compared to CON. Caudal anterior cingulate cortical thickness was increased in SCZ, PBD and NPBD. Cortical thickness in PBD and NPBD were not significantly different from controls. Significant partial correlations were observed for SAPS severity with middle temporal (r = − 0.26; p = 0.001) and fusiform (− 0.26; p = 0.001) cortical thickness.

Conclusions

Individuals with SCZ displayed significantly reduced cortical thickness in several cortical regions compared to both CON and bipolar. We found that SCZ participants had significant cortical thinning relative to CON and bipolar disorder most significantly in the frontal (i.e. paracentral), parietal (i.e. inferior parietal, supramarginal), and temporal (i.e. middle temporal, fusiform) cortices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bipolar disorder has substantial genetic and familiar overlap with schizophrenia and often share clinical features, including the presence of psychotic symptoms (Cardno and Owen 2014; Moskvina et al. 2009; Mamah and Barch 2011; Fischer and Carpenter 2009). Over 60% of bipolar disorder patients have had a lifetime history of at least one psychotic symptom (Keck et al. 2003; Coryell et al. 2001; Goodwin and Jamison 2007). Some studies have also found that schizophrenia susceptibility genes are more commonly shared with psychotic bipolar patients, compared to bipolar patients without a psychotic disorder history (Moskvina et al. 2009; Ivleva et al. 2008, 2010; Green et al. 2005; Potash 2006; Tamminga et al. 2013).

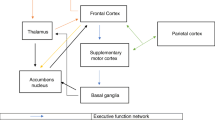

There has been continued interest in the use of neuroimaging to investigate intermediate phenotypes common across schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The cortical structure of the brain is commonly quantitatively measured via gray matter volume, a measurement that is dependent on both cortical thickness and surface area of a region. These structural measures are thought to be heritable (Panizzon et al. 2009) and can therefore provide insight into the genetic differences between patient populations. However, the surface area and cortical thickness appear to be genetically uncorrelated (Panizzon et al. 2009). Thus, volume measurements, which combine aspects of both traits, are likely influenced by some combination of these genetic factors. Cortical thickness is thought to be dependent on the size, number, and arrangement of neurons and neuroglia in the cortex (Hatton et al. 2013; Goldman-Rakic 1988; Kuperberg et al. 2003; Rakic and Caviness 1995; Winkler et al. 2010). As such, cortical thinning relative to normal populations has implications about the preservation of, or lack thereof, network architecture in the cortex. To the extent abnormal function in cortical and subcortical networks, which are thought to be perturbed in both diseases (Uhlhaas 2013; Hulshoff Pol et al. 2012; Menon 2011), can be explained by abnormality of structure, the region-specific nature of cortical thinning could provide insight into differential developmental trajectories of brain disorders (Fischl et al. 1999; Fischl and Dale 2000).

Several brain studies investigating cortical structure have been conducted in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients. A meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometric studies in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder identified overlap of gray matter deficits in paralimbic cortical regions (including the anterior cingulate and insula) across the two diagnoses, with schizophrenia patients showing more extensive cortical deficits, also including neocortical and limbic regions (Ellison-Wright and Bullmore 2010). A recent large meta-analysis by the ENIGMA schizophrenia working group found widespread cortical thinning in schizophrenia, as well as reduced surface area (van Erp et al. 2017). Similarly, Rimol et al. (2012) found widespread cortical thinning and circumscribed cortical area reductions in schizophrenia patients, but not in bipolar disorder patients. However, the largest study of cortical thickness and surface area in bipolar disorder was conducted within the ENIGMA Consortium, and involved 2447 adult bipolar disorder patients (Hibar et al. 2018). These authors found cortical thinning in frontal, temporal and parietal regions, as well as an association of reduced cortical surface area with psychosis history (Hibar et al. 2018).

Heterogeneity in patient populations studied can influence the structural imaging findings observed (Zhang et al. 2015). Thus, studying more homogenous populations may provide greater understanding of cortical thickness in disease. For example, investigating a wide age range of subjects can introduce confounds unrelated to the illness and associated with older age. Studying cortical thickness in younger and older bipolar disorder populations separately, have provided additional insights into the disease, showing substantial cortical thinning only in the older bipolar patients (Hibar et al. 2018). Studying the clinical subtypes separately, can also be valuable. Patients with bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder are sometimes pooled as one group, despite the former representing a subtype with longer duration clinical episodes (“mania”) than the latter (“hypomania”) (American_Psychiatric_Association 2013). Significant reductions in cortical volume and thickness however has been reported by some authors to be limited to bipolar I disorder patients (Maller et al. 2014; Abe et al. 2016; Rimol et al. 2010). Finally, separating bipolar patients based on psychotic disorder histories often show differential effects, usually with the psychotic bipolar patients showing structural changes more closely related to that of schizophrenia patients (Strasser et al. 2005; Mamah et al. 2016; Womer et al. 2014).

The current study compares cortical thickness between young adult (aged 18–30 years) control subjects and patients with schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar I disorder and non-psychotic bipolar I disorder. Bipolar disorder subjects all had a history of hyperthymic manic episodes, while patients with a history of exclusively irritable manic episodes were excluded. In addition, none of our participants met criteria for a substance use disorder in the past 6 months of assessment, to minimize substance related effects on cortical thickness. We hypothesized that patterns of cortical thinning in schizophrenia patients will share some similarity with psychotic but not non-psychotic bipolar disorder patients.

Methods

Participants

All participants provided written informed consent and experimental procedures were approved by the Washington University School of Medicine institutional review board. Four diagnostic groups were included in the current study: healthy controls (CON; n = 40), schizophrenia (SCZ, n = 52), psychotic bipolar I disorder (PBD, n = 49) and non-psychotic bipolar I disorder (NPBD, n = 24). Participant groups were diagnosed on the basis of a consensus between a research psychiatrist and a trained research assistant who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder (First et al. 2002; Lobbestael et al. 2011). CON subjects were required to have no lifetime history of psychotic or mood disorders. Bipolar (BD) participant patients were required to meet DSM-IV criteria for Bipolar I Disorder and were classified as psychotic BD if the participant had a psychotic event over the course of their lifetime, as assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID). All psychotic events were reported to have occurred during manic episodes in bipolar participants. Participants were excluded if they: (a) met DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence or severe/moderate abuse during the prior 6 months; (b) had a clinically unstable or severe general medical disorder; or (c) had a history of head injury with documented neurological sequelae or loss of consciousness. Additionally, to minimize clinical heterogeneity within the BD group, only participants with a history of euphoric mania (versus mania characterized by primarily irritable mood) were included in the study.

Table 1 shows demographic data across the four participant groups. All patients were on stable medication for at least 4 weeks prior to assessment. Based on the results of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), the majority of bipolar participants were euthymic at the time of admission into the study. Four participants (3 PBD, 1 NPBD) scored between 13 and 20 suggesting a potential case of hyper- or hypomania. Three participants (2 PBD, 1 NPBD) scored above 20 indicating a probable case of hyper- or hypomania (Young et al. 1978; Marchand et al. 2005). The YMRS was only collected for bipolar patients. The average duration of illness for the psychotic bipolar group was 7.87 years while the average duration of illness for the non-psychotic group was 8.58 years.

Clinical assessment

Symptoms were assessed using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Specific subscale scores were summed to derive measures of positive symptoms (i.e. hallucination, delusion) and negative symptoms (i.e. flat affect, alogia, anhedonia, attention and amotivation subscales). Disorganized symptoms were not included in SAPS scores so as to only reflect the presence of positive symptoms.

Image and cortical thickness acquisition

Magnetic resonance (MR) scans were obtained using a Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) 3T Tim TRIO Scanner at Washington University Medical School. T1-weighted images were acquired using a sagittal MPRAGE 3D sequence (TR = 2400 ms, TE = 3.16 ms, flip = 8°; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm).

Cortical thickness of 34 brain cortical regions for each hemisphere were obtained using FreeSurfer version 5.1.0 software (Fischl et al. 1999; Dale et al. 1999). Gray-matter (GM) and white-matter (WM) boundaries were reconstructed in order to estimate the distance between those surfaces across the cortex in order to calculate the cortical thickness (Dale et al. 1999; Han et al. 2006; Rosas et al. 2002). Our preprocessing included automated skull stripping, removal of subcortical surfaces, transformation into Talairach space, and a spatial smoothing algorithm (Dale et al. 1999). Measurements of intracranial volume (ICV) were determined via the automated Freesurfer pipeline. These surfaces were then inflated into spheres in order to be registered to a common space via an automated procedure based on identification of cortical features identified in a predefined atlas (Fischl et al. 1999). Thickness for each region of interest (ROI) was calculated on a per-vertex basis based on the distance between closest points between gray and white-matter surfaces and then averaged across vertices within each region of interest (Fischl et al. 1999; Dale et al. 1999).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM’s SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 24.0, Armonk, NY). We examined group differences in SAPS and SANS measures using a multivariate analysis of covariance, covarying for age and sex. Differences in cortical thickness between subjects of different diagnostic groups were initially tested using a repeated measures analysis of covariance, covaried for age, sex, and ICV, treating hemisphere and region as repeated-measures. ICV was used here as a covariate given past evidence of cranial size differences in individuals with schizophrenia (Ward et al. 1996). This repeated-measures test revealed no main effect of hemisphere. Thus, subsequent testing was performed on cortical thickness values averaged across hemisphere in order to reduce the number tests for multiple comparisons considerations. We then tested for univariate effects of diagnostic group on cortical thickness within each region, with post hoc analyses of pairwise differences in groups in regions showing a univariate effect. To assess the relationship between clinical variables and cortical thickness, we performed a set of linear regressions to predict SAPS and SANS scores for each ROI. Included in these models were predictors for age, sex, ICV as well as dummy predictors for SCZ, PBD, and NPBD group membership in addition to a cortical thickness regressor. Given the number of regions tested, multiple comparisons corrections are noted when performed.

Results

Clinical measures

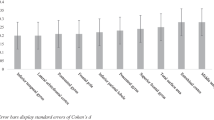

Based on multivariate testing, there was a significant main effect of diagnosis (F(6,310) = 20.530, Wilk’s Λ = 0.512, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.284) after controlling for age and sex, indicating a difference in SAPS and SANS scores between groups. Differences in scores were driven by higher ratings in the SCZ and PBD groups relative to controls (CON) in the SAPS data, and SCZ relative to all other groups in the SANS scores (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Clinical measures of positive and negative symptoms by diagnosis. (left) Relationship between positive symptoms by diagnosis as assessed by SAPS. (right) Negative symptom scores as assessed by SANS by diagnosis. Significant pairwise comparisons shown in both figures, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons. Error bars represent within-group standard error

Group analysis of cortical thickness

Covarying for sex, age, and ICV, a repeated-measures test of cortical thickness showed a significant main effect of diagnosis (F(3,158) = 5.664, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.058; Fig. 2) and region (F(33,514) = 23.074, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.127), but no effect of hemisphere (F(1,158) = 3.650, p = 0.057, η2 = 0.021). We observed a group by hemisphere interaction (F(3,158) = 8.879, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.144), driven by decreased right hemisphere thickness in the CON and SCZ groups relative to BD groups.

Average cortical thickness per hemisphere by diagnosis. In repeated-measures testing, a significant main effect of diagnosis was observed, with no significant main effect of hemisphere. Significance comparisons represent pairwise contrasts between diagnostic groups. Significance values greater than 0.05 not shown. Pairwise comparisons were Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons. Error bars represent within-group standard error

Further tests of cortical thickness averaged values across hemisphere to produce 34 cortical regions of interest to reduce the number of tests performed, given the lack of a main effect of hemisphere. Table 2 shows the results of 34 univariate tests, one for each region. After Bonferroni correction, significant effect of diagnosis was observed for the superior frontal cortex, paracentral cortex, the fusiform gyrus, as well as the caudal anterior and posterior portions of the cingulate. For visualization purposes, mean, z-scored cortical thickness values of the 34 cortical regions are depicted in Fig. 3.

Z-scored, average cortical thickness values per region of interest. Region of interest labels correspond to those identified in Table 2. Z-scores were computed by using the mean and standard deviation of the control group as reference, and as such the healthy controls lie on the horizontal axis. Error bars represent within-group standard error

Results of post hoc analyses, comparing cortical thickness between individual groups in regions that showed an omnibus group effect (prior to Bonferroni correction), are shown in Table 3. After Bonferroni correction, pairwise comparisons showed cortical thinning in SCZ participants relative to other groups, most notably in specific frontal, parietal and temporal regions. However, the thickness of the anterior cingulate cortex was increased in SCZ, PBD, and NPBD participants compared to CON participants. Cortical thickness in the posterior cingulate was larger in NPBD compared to CON participants. There were no other significant cortical thickness abnormalities in either PBD or NPBD compared to CON.

Clinical relationships of cortical thickness

We performed linear regressions to predict SAPS and SANS scores based on cortical thickness, diagnostic group membership, and covariates (age, sex, and ICV). All regression models significantly predicted SAPS scores (F’s(7,157) > 11.601, p’s < 0.001) and a diagnosis of SCZ (p’s < 0.001) or bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms (p’s < 0.005) predicted higher SAPS. The partial correlations associated with the cortical thickness of each region, as well as the significance of those parameter estimates is shown in Table 4. After Bonferroni correction for multiple (34) tests, two regions showed significant correlations with SAPS: the middle temporal gyrus (r = − 0.257) and the fusiform area (r = − 0.255). Several additional regions were significant prior to correction for multiple comparisons including frontal (pars triangularis, lateral orbitofrontal), parietal (inferior parietal, supramarginal, precuneus) and temporal (inferior temporal, bank of the superior temporal sulcus, entorhinal) areas.

All regression models also significantly predicted SANS scores (F’s(7,157) > 23.780, p’s < 0.001), with SCZ (p’s < 0.001) or psychotic BD (p’s < 0.005) predicting higher SANS scores. After correcting for multiple comparisons, no region’s cortical thickness predicted negative symptom scores. Partial correlations prior to multiple comparisons correction are shown in Table 5. Regions that were significant prior to multiple comparisons correction included frontal (middle frontal gyrus), parietal (inferior parietal), and temporal (inferior temporal, fusiform) regions.

Discussion

Our study investigated cortical thickness in young adult patients with schizophrenia and relatively homogenous clinical subgroups of bipolar I disorder patients, comprising of psychotic—(PBD) and non-psychotic (NPBD) patients with hyperthymic mania histories. We found that SCZ participants had significant cortical thinning relative to CON and BD most significantly in the frontal (i.e. paracentral), parietal (i.e. inferior parietal, supramarginal), and temporal (i.e. middle temporal, fusiform) cortices. Our results are consistent with that of most other studies which found cortical thinning in SCZ relative to control populations across a wide range of cortical regions, usually including parts of the frontal and temporal cortex (van Erp et al. 2017; Rimol et al. 2012; Sugihara et al. 2017; Knochel et al. 2016; Besteher et al. 2016; Nenadic et al. 2015; Goldman et al. 2009). A recent meta-analysis of 4474 SCZ subjects found that the largest effect sizes for lower cortical thickness compared to controls were present in the fusiform, inferior frontal (pars opercularis), lateral orbitofrontal, temporal (inferior/medial/superior), parahippocampal, insula, isthmus cingulate, and the posterior cingulate cortices (van Erp et al. 2017). Despite some inconsistencies in the specific affected regions across schizophrenia studies, which likely reflects the biological heterogeneity of patients and methodological differences, cortical thinning is considered a key pathology underlying schizophrenia. Interestingly, we also found increased cortical thickness in an isolated region—the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)—in the schizophrenia group, as well as in both groups of bipolar disorder subjects. The ACC is a brain region critical for integrating cognitive and emotional functions in support of adaptive, goal-directed behavior (Devinsky et al. 1995). Increased ACC thickness in our subjects do not appear to be driven primarily by their relatively young age, as ACC thinning has also been seen in youth at clinically high risk for developing schizophrenia (Jung et al. 2011; Yucel et al. 2003). These findings in our patient groups differ from other studies that found gray matter reduction in the ACC in schizophrenia (Fornito et al. 2009a; Bouras et al. 2001; Hanford et al. 2016). However, increased ACC thickness has been reported in male first episode psychosis in bipolar disorder (Fornito et al. 2009b). These authors suggested that hypertrophy of regions critical for regulating the HPA axis, including the ACC, amygdala and pituitary gland, in early psychosis may be associated with an elevated stress response, which ultimately results in volumetric contraction with chronic illness. A few other authors also found increased ACC thickness in either first-episode (Adler et al. 2007) or chronic (Adler et al. 2005; Bearden et al. 2007) bipolar disorder, which was also been attributable to lithium effects in one study (Bearden et al. 2007) but not others (Fornito et al. 2009; Adler et al. 2007). Taken together, these findings suggest that while widespread cortical thinning is pathognomonic of schizophrenia, increased ACC thickness in some schizophrenia cohorts may reflect a hyperfunctional abnormality that produces an excessive stress response.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find similar cortical thinning in PBD as we found in schizophrenia. Cortical thickness in both PBD and NPBD were comparable into controls, other than the increased ACC discussed above. It is notable that several other regions were larger in bipolar patients than in controls, albeit non-significantly. While these findings differ from those from a recent systematic review of bipolar disorder which reported cortical thinning in bipolar disorder (Hanford et al. 2016), normal cortical thickness have also been reported (Rimol et al. 2010, 2012). The ENIGMA Consortium conducted the largest cortical analysis of bipolar disorder patients, involving 6503 subjects and found bilateral frontal, temporal and parietal cortical thinning, especially in the left pars opercularis, fusiform gyrus and rostral middle frontal cortex (Hibar et al. 2018). When cortical thinning is observed in bipolar disorder, it is however not as pronounced as it is in schizophrenia and sometimes involves different brain regions (Knochel et al. 2016). Cortical thinning found in some bipolar disorder studies but not others appears to be due to differences in the populations studied. For example, older age and illness chronicity would be expected to lead to greater cortical thinning in bipolar disorder patients. Our study involved bipolar disorder subjects who on average, were in their mid-twenties, while most other bipolar studies include older populations. The ENIGMA bipolar study included older patients (grand mean age across sites was 37.5 years) found notably greater cortical thinning when comparing older BD patients to controls, than when younger bipolar patients were compared to controls (Hibar et al. 2018). Thus, cortical thinning may be a later presentation of bipolar disorder, which would not be evident in younger adults. Our bipolar disorder population also consisted of a more homogenous clinical cohort than those in most other studies, including only bipolar 1 disorder patients with hyperthymic manic histories. Although not directly investigated, it is plausible that bipolar disorder with hyperthymic mania may be associated with less cortical thinning than with irritable mania. Future studies comparing bipolar disorder patients based on their manic presentation, may clarify their relationship to brain structure. Finally, differences in cortical findings across studies may be related to differences in the medication and recreational drug use of the patient cohorts. Psychotropic medications used in bipolar disorder have been associated with both increased cortical thickness (e.g. lithium) (Giakoumatos et al. 2015) and cortical thinning (e.g. typical antipsychotics) (van Haren et al. 2011). Similarly, recreational substances can also exacerbate cortical thinning in patients (Hartberg et al. 2018). Our study design excluded those with a significant substance use comorbidity (i.e. substance use disorder in last 6 months), and therefore may have represented a healthier cohort with less cortical abnormality.

We did not find any notable differences between our clinical subgroups of bipolar disorder subjects. Cortical and subcortical volumetric deficits have been reported in psychotic compared to nonpsychotic bipolar disorder (Strasser et al. 2005; Altamura et al. 2017). However, consistent with our study, the ENIGMA group did not find a relationship of psychosis history and cortical thickness in bipolar subjects, although they reported an association of psychosis with surface area in isolated brain regions (Hibar et al. 2018). Thus, cortical surface or volume, which were not investigated in our study, may be more sensitive in discriminating these clinical subtypes of bipolar disorder. PBD has been reported to represent a clinical construct more closely related to schizophrenia than NPBD, based on clinical presentation, familial and genetic overlap (Moskvina et al. 2009; Ivleva et al. 2008, 2010; Green et al. 2005; Potash 2006; Tamminga et al. 2013). PBD patients also show greater cognitive dysfunction compared to NPBD, approximating that seen in schizophrenia (Martinez-Aran et al. 2008; Simonsen et al. 2011; Bourne et al. 2013).

Our results showed that the cortical thickness of several brain regions correlated with measures of positive and negative symptoms, although only relationships between temporal regions and positive symptoms survived multiple comparisons correction. The observed correlations however may have been minimized by confounders, which were not adequately corrected. For example, the recorded SAPS and SANS scores reflect symptom severity within the previous 2 weeks, and often fluctuate over time. Additionally, dimensional ratings for depression were not collected for the current study. Considering that the period between symptom assessment and brain scanning varied across patients and were in some cases lengthy (median: 14 days; mean: 19 days), clinical symptoms during scanning may not be properly captured by our instruments. In the future, studying associations with clinical measures of chronic symptoms severity, such as the Washington Early Recognition Affectivity and Psychosis (WERCAP) Screen (Hsieh et al. 2016; Mamah et al. 2014), may be more accurate in uncovering brain-behavior relationships.

Numerous factors may contribute to cortical thinning, including changes in the number, density and arrangement of cells in the cortical sheet (Hatton et al. 2013; Goldman-Rakic 1988; Kuperberg et al. 2003; Rakic and Caviness 1995). Post-mortem examination of SCZ have shown reduced neuronal size and neuropil (Rimol et al. 2012; Tandon et al. 2008; Harrison 1999). Others have reported decreases in glial density and proliferation, indicating a relative lack of gliosis (Tandon et al. 2008; Harrison 1999; Phillips et al. 2008) as well as an increase in synaptic apoptosis leading to reduced synaptic integrity in pyramidal neurons (Glantz and Lewis 2000). Decreased glial density, reduced neuronal size, and synaptic degeneration have also been observed in BD to a lesser extent than in SCZ (Tandon et al. 2008; Harrison 2002). Most of these changes are believed to be neurodevelopmental in origin (Harrison 1999, 2002; Phillips et al. 2008; Rapoport et al. 2005; Lewis and Levitt 2002) supported by reports of cortical thinning in medication naïve subjects (Narr et al. 2005a, b; Lyoo et al. 2006), as well as prior to disease onset (Ellison-Wright and Bullmore 2010; Tandon et al. 2008; Harrison 1999) and in unaffected relatives (Goghari et al. 2007).

There are some limitations to our study. Firstly, medications can influence cortical thickness, which could disproportionately affect SCZ and BD participants. Considering our sample size and the complexity of medications and doses, our current study was not adequately designed to decipher medication related effects. Typical antipsychotics, such as haloperidol, have been found to cause regional cortical thinning across wide ranges of cortical regions including frontal, temporal, and parietal areas (Dazzan et al. 2005; Lieberman et al. 2005; Navari and Dazzan 2009), in addition to increased basal ganglia volumes (Dazzan et al. 2005; Smieskova et al. 2009). Atypical antipsychotics have been associated with more muted cortical thinning compared to typical antipsychotics (Navari and Dazzan 2009; Mamah et al. 2012), and antidepressants (Duman and Monteggia 2006; Lim et al. 2012) and lithium (Bearden et al. 2007; Hafeman et al. 2012) have neurotrophic effects, which are believed to underlie symptomatic improvement. Secondly, our study results may also have been influenced by gender disparity across groups. Our subjects consisted of more males than females in the SCZ group, and more females in the BD groups. Thicker cortices have been found in regionally in women compared to men in some (Sowell et al. 2007; Koolschijn and Crone 2013; Savic and Arver 2014) but not all (Raznahan et al. 2011) studies. Sex related differences have also been reported in cortical surface area, as well as neuronal and synaptic density (Rabinowicz et al. 1999; Luders et al. 2004; Alonso-Nanclares et al. 2008). While our statistical design, treating gender as a covariate, may reduce some of this potential confound, matching studies by gender would lead to more accurate results. Finally, our study was not well powered to investigate group differences in each individual brain region. In order to reduce the number of tests performed when examining relationships between cortical thickness and symptom measures, we collapsed across hemisphere. While cortical thickness in most regions correlated across hemispheres, a group by hemisphere interaction was observed. Thus, group differences in regional cortical thickness in our patients may be specific to individual hemispheres.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our studies investigated cortical thickness in a relatively homogenous groups of young adult schizophrenia patients and bipolar I disorder patients with hyperthymic manic histories. Regions of decreased cortical thickness were observed in schizophrenia patients, but not in either psychotic or non-psychotic bipolar patients. Thickness of the anterior cingulate cortex was increased in all patient groups. Clinical and demographic heterogeneity in patient populations may explain inconsistent findings across studies.

Abbreviations

- B-SNIP:

-

Bipolar–Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes

- BD:

-

bipolar disorder

- CON:

-

healthy controls

- ICV:

-

intracranial volume

- GM:

-

gray matter

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NPBD:

-

bipolar disorder with no psychotic features

- PBD:

-

bipolar disorder with psychotic features

- ROI:

-

region of interest

- SANS:

-

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms

- SAPS:

-

Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms

- SCID-I:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

- SCID-II:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders

- SCZ:

-

schizophrenia

- WM:

-

white matter

- YMRS:

-

Young Mania Rating Scale

References

Abe C, Ekman CJ, Sellgren C, Petrovic P, Ingvar M, Landen M. Cortical thickness, volume and surface area in patients with bipolar disorder types I and II. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41(4):240–50.

Adler CM, Levine AD, DelBello MP, Strakowski SM. Changes in gray matter volume in patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(2):151–7.

Adler CM, DelBello MP, Jarvis K, Levine A, Adams J, Strakowski SM. Voxel-based study of structural changes in first-episode patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(6):776–81.

Alonso-Nanclares L, Gonzalez-Soriano J, Rodriguez JR, DeFelipe J. Gender differences in human cortical synaptic density. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14615–9.

Altamura AC, Maggioni E, Dhanoa T, et al. The impact of psychosis on brain anatomy in bipolar disorder: a structural MRI study. J Affect Disord. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.092.

American_Psychiatric_Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Bearden CE, Thompson PM, Dalwani M, et al. Greater cortical gray matter density in lithium-treated patients with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(1):7–16.

Besteher B, Wagner G, Koch K, et al. Pronounced prefronto-temporal cortical thinning in schizophrenia: neuroanatomical correlate of suicidal behavior? Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):151–7.

Bouras C, Kovari E, Hof PR, Riederer BM, Giannakopoulos P. Anterior cingulate cortex pathology in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102(4):373–9.

Bourne C, Aydemir O, Balanza-Martinez V, et al. Neuropsychological testing of cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar disorder: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128(3):149–62.

Cardno AG, Owen MJ. Genetic relationships between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(3):504–15.

Coryell W, Leon AC, Turvey C, Akiskal HS, Mueller T, Endicott J. The significance of psychotic features in manic episodes: a report from the NIMH collaborative study. J Affect Disord. 2001;67(1–3):79–88.

Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–94.

Dazzan P, Morgan KD, Orr K, et al. Different effects of typical and atypical antipsychotics on grey matter in first episode psychosis: the AESOP study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(4):765–74.

Devinsky O, Morrell MJ, Vogt BA. Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain. 1995;118(Pt 1):279–306.

Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1116–27.

Ellison-Wright I, Bullmore E. Anatomy of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;117(1):1–12.

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 2002.

Fischer BA, Carpenter WT Jr. Will the Kraepelinian dichotomy survive DSM-V? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(9):2081–7.

Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(20):11050–5.

Fischl B, Sereno MI, Dale AM. Cortical surface-based analysis. II: inflation, flattening, and a surface-based coordinate system. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):195–207.

Fornito A, Yucel M, Dean B, Wood SJ, Pantelis C. Anatomical abnormalities of the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia: bridging the gap between neuroimaging and neuropathology. Schizophr Bull. 2009a;35(5):973–93.

Fornito A, Yucel M, Wood SJ, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex abnormalities associated with a first psychotic episode in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2009b;194(5):426–33.

Giakoumatos CI, Nanda P, Mathew IT, et al. Effects of lithium on cortical thickness and hippocampal subfield volumes in psychotic bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;61:180–7.

Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):65–73.

Goghari VM, Rehm K, Carter CS, MacDonald AW 3rd. Regionally specific cortical thinning and gray matter abnormalities in the healthy relatives of schizophrenia patients. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(2):415–24.

Goldman AL, Pezawas L, Mattay VS, et al. Widespread reductions of cortical thickness in schizophrenia and spectrum disorders and evidence of heritability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(5):467–77.

Goldman-Rakic PS. Topography of cognition: parallel distributed networks in primate association cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:137–56.

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Green EK, Raybould R, Macgregor S, et al. Operation of the schizophrenia susceptibility gene, neuregulin 1, across traditional diagnostic boundaries to increase risk for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):642–8.

Hafeman DM, Chang KD, Garrett AS, Sanders EM, Phillips ML. Effects of medication on neuroimaging findings in bipolar disorder: an updated review. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(4):375–410.

Han X, Jovicich J, Salat D, et al. Reliability of MRI-derived measurements of human cerebral cortical thickness: the effects of field strength, scanner upgrade and manufacturer. Neuroimage. 2006;32(1):180–94.

Hanford LC, Nazarov A, Hall GB, Sassi RB. Cortical thickness in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(1):4–18.

Harrison PJ. The neuropathology of schizophrenia. A critical review of the data and their interpretation. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 4):593–624.

Harrison PJ. The neuropathology of primary mood disorder. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 7):1428–49.

Hartberg CB, Lange EH, Lagerberg TV, et al. Cortical thickness, cortical surface area and subcortical volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patients with cannabis use. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):37–47.

Hatton SN, Lagopoulos J, Hermens DF, Scott E, Hickie IB, Bennett MR. Cortical thinning in young psychosis and bipolar patients correlate with common neurocognitive deficits. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2013;1:3.

Hibar DP, Westlye LT, Doan NT, et al. Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder: an MRI analysis of 6503 individuals from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):932–42.

Hsieh CJ, Godwin D, Mamah D. Utility of washington early recognition center self-report screening questionnaires in the assessment of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:149.

Hulshoff Pol HE, van Baal GC, Schnack HG, et al. Overlapping and segregating structural brain abnormalities in twins with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):349–59.

Ivleva E, Thaker G, Tamminga CA. Comparing genes and phenomenology in the major psychoses: schizophrenia and bipolar 1 disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(4):734–42.

Ivleva EI, Morris DW, Moates AF, Suppes T, Thaker GK, Tamminga CA. Genetics and intermediate phenotypes of the schizophrenia–bipolar disorder boundary. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(6):897–921.

Jung WH, Kim JS, Jang JH, et al. Cortical thickness reduction in individuals at ultra-high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(4):839–49.

Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Havens JR, et al. Psychosis in bipolar disorder: phenomenology and impact on morbidity and course of illness. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(4):263–9.

Knochel C, Reuter J, Reinke B, et al. Cortical thinning in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;172(1–3):78–85.

Koolschijn PC, Crone EA. Sex differences and structural brain maturation from childhood to early adulthood. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2013;5:106–18.

Kuperberg GR, Broome MR, McGuire PK, et al. Regionally localized thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):878–88.

Lewis DA, Levitt P. Schizophrenia as a disorder of neurodevelopment. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:409–32.

Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):361–70.

Lim HK, Jung WS, Ahn KJ, et al. Regional cortical thickness and subcortical volume changes are associated with cognitive impairments in the drug-naive patients with late-onset depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(3):838–49.

Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID I) and Axis II disorders (SCID II). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(1):75–9.

Luders E, Narr KL, Thompson PM, et al. Gender differences in cortical complexity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(8):799–800.

Lyoo IK, Sung YH, Dager SR, et al. Regional cerebral cortical thinning in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(1):65–74.

Maller JJ, Thaveenthiran P, Thomson RH, McQueen S, Fitzgerald PB. Volumetric, cortical thickness and white matter integrity alterations in bipolar disorder type I and II. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:118–27.

Mamah D, Barch DM. Diagnosis and classification of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In: Ritsner MS, editor. Handbook of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, vol. 1. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011. p. 45–83.

Mamah D, Harms MP, Barch D, Styner M, Lieberman JA, Wang L. Hippocampal shape and volume changes with antipsychotics in early stage psychotic illness. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:96.

Mamah D, Owoso A, Sheffield JM, Bayer C. The WERCAP screen and the WERC stress screen: psychometrics of self-rated instruments for assessing bipolar and psychotic disorder risk and perceived stress burden. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(7):1757–71.

Mamah D, Alpert KI, Barch DM, Csernansky JG, Wang L. Subcortical neuromorphometry in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;11:276–86.

Marchand WR, Clark SC, Wirth L, Simon C. Validity of the parent young mania rating scale in a community mental health setting. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005;2(3):31–5.

Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Tabares-Seisdedos R, et al. Neurocognitive impairment in bipolar patients with and without history of psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(2):233–9.

Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(10):483–506.

Moskvina V, Craddock N, Holmans P, et al. Gene-wide analyses of genome-wide association data sets: evidence for multiple common risk alleles for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and for overlap in genetic risk. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(3):252–60.

Narr KL, Bilder RM, Toga AW, et al. Mapping cortical thickness and gray matter concentration in first episode schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2005a;15(6):708–19.

Narr KL, Toga AW, Szeszko P, et al. Cortical thinning in cingulate and occipital cortices in first episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2005b;58(1):32–40.

Navari S, Dazzan P. Do antipsychotic drugs affect brain structure? A systematic and critical review of MRI findings. Psychol Med. 2009;39(11):1763–77.

Nenadic I, Yotter RA, Sauer H, Gaser C. Patterns of cortical thinning in different subgroups of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(6):479–83.

Panizzon MS, Fennema-Notestine C, Eyler LT, et al. Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(11):2728–35.

Phillips ML, Ladouceur CD, Drevets WC. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(9):829, 833–57.

Potash JB. Carving chaos: genetics and the classification of mood and psychotic syndromes. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):47–63.

Rabinowicz T, Dean DE, Petetot JM, de Courten-Myers GM. Gender differences in the human cerebral cortex: more neurons in males; more processes in females. J Child Neurol. 1999;14(2):98–107.

Rakic P, Caviness VS Jr. Cortical development: view from neurological mutants two decades later. Neuron. 1995;14(6):1101–4.

Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MR. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(5):434–49.

Raznahan A, Shaw P, Lalonde F, et al. How does your cortex grow? J Neurosci. 2011;31(19):7174–7.

Rimol LM, Hartberg CB, Nesvag R, et al. Cortical thickness and subcortical volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(1):41–50.

Rimol LM, Nesvag R, Hagler DJ Jr, et al. Cortical volume, surface area, and thickness in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(6):552–60.

Rosas HD, Liu AK, Hersch S, et al. Regional and progressive thinning of the cortical ribbon in Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 2002;58(5):695–701.

Savic I, Arver S. Sex differences in cortical thickness and their possible genetic and sex hormonal underpinnings. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(12):3246–57.

Simonsen C, Sundet K, Vaskinn A, et al. Neurocognitive dysfunction in bipolar and schizophrenia spectrum disorders depends on history of psychosis rather than diagnostic group. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(1):73–83.

Smieskova R, Fusar-Poli P, Allen P, et al. The effects of antipsychotics on the brain: what have we learnt from structural imaging of schizophrenia?—a systematic review. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(22):2535–49.

Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Kan E, et al. Sex differences in cortical thickness mapped in 176 healthy individuals between 7 and 87 years of age. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(7):1550–60.

Strasser HC, Lilyestrom J, Ashby ER, et al. Hippocampal and ventricular volumes in psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar patients compared with schizophrenia patients and community control subjects: a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):633–9.

Sugihara G, Oishi N, Son S, Kubota M, Takahashi H, Murai T. Distinct patterns of cerebral cortical thinning in schizophrenia: a neuroimaging data-driven approach. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(4):900–6.

Tamminga CA, Ivleva EI, Keshavan MS, et al. Clinical phenotypes of psychosis in the bipolar–schizophrenia network on intermediate phenotypes (B-SNIP). Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1263–74.

Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, “Just the Facts”: what we know in 2008 part 1: overview. Schizophr Res. 2008;100(1–3):4–19.

Uhlhaas PJ. Dysconnectivity, large-scale networks and neuronal dynamics in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(2):283–90.

van Erp T, Hibar D, Walton E, et al. Cortical abnormalities in schizophrenia: an ENIGMA schizophrenia working group meta-analysis. Organization of Human Brain Mapping, Annual Meeting; June 26, 2017; Vancouver, Canada.

van Haren NE, Schnack HG, Cahn W, et al. Changes in cortical thickness during the course of illness in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(9):871–80.

Ward KE, Friedman L, Wise A, Schulz SC. Meta-analysis of brain and cranial size in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1996;22(3):197–213.

Winkler AM, Kochunov P, Blangero J, et al. Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage. 2010;53(3):1135–46.

Womer FY, Wang L, Alpert KI, et al. Basal ganglia and thalamic morphology in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2014;223(2):75–83.

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35.

Yucel M, Wood SJ, Phillips LJ, et al. Morphology of the anterior cingulate cortex in young men at ultra-high risk of developing a psychotic illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:518–24.

Zhang T, Koutsouleris N, Meisenzahl E, Davatzikos C. Heterogeneity of structural brain changes in subtypes of schizophrenia revealed using magnetic resonance imaging pattern analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(1):74–84.

Authors’ contributions

DM and LW were involved in the design and data acquisition of the study. DG and DM wrote the manuscript. DG and KA provided data and statistical analysis. LW and DM oversaw the research and provided additional interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Cortical thickness data to be made available by contacting corresponding author with appropriate requests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in study of human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Washington University School of Medicine institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written, informed consent was provided by all participants in the study.

Funding

This study was funded by NIMH grants K08 MH085958 and R01 MH104414 to Dr. Daniel Mamah. Additionally, this work was funded by the Taylor Family Institute and the Center for Brain Research on Mood Disorders in the department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Godwin, D., Alpert, K.I., Wang, L. et al. Regional cortical thinning in young adults with schizophrenia but not psychotic or non-psychotic bipolar I disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord 6, 16 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-018-0124-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-018-0124-x