Abstract

Background

Biologgers have contributed greatly to studies of animal movement, behaviours and physiology. Accelerometers, among the various on-board sensors of biologgers, have mainly been used for animal behaviour classification and energy expenditure estimation. However, a general principle for the combined sampling duration and frequency for different taxa is lacking. In this study, we evaluated whether Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem applies to accelerometer-based classification of animal behaviour and energy expenditure approximation. To evaluate the influence of accelerometer sampling frequency on behaviour classification, we annotated accelerometer data from seven European pied flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) freely moving in aviaries. We also used simulated data to systematically evaluate the combined effect of sampling duration and sampling frequency on the performance of estimating signal frequency and amplitude.

Results

We found that a sampling frequency higher than Nyquist frequency at 100 Hz was needed to classify fast, short-burst behavioural movements of pied flycatcher, such as swallowing food with a mean frequency of 28 Hz. In contrast, high frequency movements with longer durations such as flight could be characterized adequately using much lower sampling frequency of 12.5 Hz. To identify rapid transient prey catching manoeuvres within these flight bouts, again a high frequency sampling at 100 Hz was needed. For both the experimental data of the flycatchers and the simulated data, the combination of sampling frequency and sampling duration affected the accuracy of signal frequency and amplitude estimation. For long sampling durations, the sampling frequency equal to the Nyquist frequency was adequate for accurate signal frequency and amplitude estimation. Accuracy declined with decreasing sampling duration, especially for signal amplitude estimation with up to 40% standard deviation of normalized amplitude difference. To accurately estimate signal amplitude at low sampling duration, a sampling frequency of four times the signal frequency was necessary (two times the Nyquist frequency).

Conclusions

The appropriate sampling frequency of accelerometers depends on the objective of the specific study and the characteristics of the behaviour. For studies with no constraints on device battery and storage, a sampling frequency of at least two times the Nyquist frequency will achieve relative optimal representative of signal information (i.e., frequency and amplitude). For classification and energy expenditure estimation of short-burst behaviours, 1.4 times the Nyquist frequency of behaviour is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Animal ecology research has benefited from miniaturized, energy efficient and multi-sensor biologgers [1, 2], which allows researchers to track animals in space and time [3], while also characterizing behavioural and physiological properties [4, 5]. Accelerometers have been applied to behaviour classification and estimating energy expenditure from accelerometer data in free moving animals [6], ranging from small songbirds (e.g., [7]) to large mammals (e.g., [8]). Furthermore, researchers have investigated various protocols of accelerometer attachment and sampling settings. These efforts show that the performance of both behavioural classification [9] and energy expenditure estimations [10] depends on accelerometer sampling frequency, window length for data analysis, and logger placement on the animal [11,12,13,14]. In addition, Garde et al. [11] stressed the importance of accelerometer calibration before logger attachment on animals.

Although biologging devices are becoming smaller and more energy efficient, constraints on device storage and battery capacity still exist. High sampling rates of accelerometer will cause faster battery drainage and faster filling of the memory. For example, Khan et al. [15] indicated that sampling accelerometer data at 25 Hz would result in more than double the battery life compared with sampling at 100 Hz. Obviously, sampling at 100 Hz would fill the device memory four times faster than sampling at 25 Hz. On the other hand, a low sampling rate might cause loss of information. Therefore, researchers need to optimize accelerometer sampling rate based on their specific research aim.

To evaluate how accelerometer sampling frequency settings influence performance of animal behaviour classification and estimated energy expenditure, researchers have usually sampled accelerometer data at a relatively high frequency and gradually down-sampled data from the original dataset. The performance metrics of each sampling frequency were then compared to determine the critical frequencies for appropriate preservation of information. In general, improved accuracy of behaviour classification was achieved using relatively high sampling frequency. Lok et al. [16] found walking and food ingesting behaviours of Eurasian spoonbills (Platalea leucorodia) could be better classified using accelerometer data sampled at 20 Hz compared with samples at 2, 5, and 10 Hz. Broell et al. [9] recommended using high frequency (> 30 Hz) accelerometer data for a bony fish, great sculpin (Myoxocephalus polyacanthocephalus), to detect short-burst (i.e., only last a couple of movement cycles and over time scales of order 100 ms) behaviours such as feeding and escape events. For a study on a larger cartilaginous fish, lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris), Hounslow et al. [17] found that short-burst behaviours (i.e., burst, chafe, and headshake) could be classified relatively well using accelerometer already at sampling frequency above 5 Hz. Walton et al. [18] showed that behaviour classification for sheep (i.e., lying, walking, and standing) performed best using accelerometer data sampled at 32 Hz, although the performance gain on data sampled beyond 16 Hz was marginal. In contrast, when using accelerometer measurements for estimating animal field energy expenditure (e.g., overall dynamic body acceleration—ODBA), Halsey et al. [10] suggested using a low accelerometer sampling frequency (i.e., from 10 down to 0.2 Hz). The calculations of ODBA were consistent over a 5-min window of chickens walking on a treadmill at 0.8 km h−1. Other studies also found that amplitude related metrics from accelerometer data such as VeDBA (vector of dynamic body acceleration) can be a good approximation for energy expenditure approximation [19]. In addition, signal frequency information from accelerometer data is one of the main determinants of aerodynamic power output of a flapping bird flight [20]. Although the above-mentioned studies evaluated the influence of accelerometer sampling frequency on animal behaviour classification and energy expenditure proxies, the choices of frequency were often based on trial-and-error and did not include conclusions based on a systematic evaluation.

Various studies stress the importance of the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem [21] in accelerometer data collection, which states that the sampling frequency should be at least twice the frequency of the fastest body movement essential to characterize that behaviour [1, 6, 22,23,24]. When the sampling frequency is lower than the Nyquist frequency, signal aliasing will cause a distortion effect on the original signal. However, none of these previous works explicitly tested this theorem in the context of their work on animal behaviour classification or energy expenditure approximation. Therefore, several questions remain unanswered about this theorem in the context of accelerometer-based research. For example, would samples at the exact Nyquist frequency be adequate for behaviour classification and energy expenditure estimation? Or would oversampling (i.e., higher than Nyquist frequency) provide additional value of increased accuracy?

The aim of this study was to evaluate the appropriate sampling frequency regarding the Nyquist–Shannon theorem with respect to behaviour classification and energy expenditure approximation using accelerometer data from freely moving birds. We collected accelerometer data from European pied flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) in aviaries to evaluate the influence of different sampling frequencies relative to the Nyquist frequency on behaviour classification results. We specifically analyzed flying and swallowing behaviours of pied flycatchers. The accelerometer data of flying were representative of long-endurance, rhythmic waveform patterns, whereas the accelerometer data of swallowing were representative of short-burst, abrupt waveform patterns. In addition, we used both flight accelerometer data from pied flycatchers and simulated data to evaluate the influence of sampling frequency and window length used to derive two accelerometer data metrics: movement frequency (such as wingbeat frequency) and amplitude, which are important for energy expenditure approximation.

Materials and methods

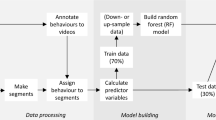

The methods in this study consist of analyses on accelerometer data collected from captive pied flycatchers and simulated data (Fig. 1).

Experimental data collection and analysis

The accelerometer loggers used in this study were developed by the Electronics lab at the Department of Biology, Lund University, Sweden. The small loggers (18 × 9 × 2 mm, W × L × H) weighed 0.7 g and were powered by a zink-air button cell (A10, 100 mAh capacity). The accelerometer unit recorded three-axis accelerations (x-axis: lateral; y-axis: longitudinal; z-axis: vertical) with a sampling frequency at around 100 Hz, a measurement acceleration range of ± 8 g (where g = 9.81 ms−2), and an 8-bit output resolution for each axis. As a result, the loggers had 256 output levels at a resolution of 0.063 g. The loggers had been programmed to start logging tri-axial acceleration at the next full hour after the hour from activation. Once logging had started the logger recorded data continuously for about 30 min, limited by on-board memory size that could hold approximately 175,000 individual 3-axis recordings.

Experiments were performed with seven (pre-breeding) male European pied flycatchers caught in the wild at Vombs fure, Lund, Sweden. The birds were caught when they inspected potential nest boxes using either mist nets or spring-loaded aluminium trap doors at the entrance hole inside the nest box. Each bird was weighed and ringed after being caught, and then transported to individual-based aviaries (measuring 5 × 3 × 2 m in length × width × height) at the Stensoffa field station (55°41′42″N, 13°26′50″E), approximately 8 km west of the catching site. During captivity, birds were given food (i.e., mealworms) and water ad libitum. The captive periods ranged from 3 to 7 days, with the majority being kept for 3–4 days. All birds were released back to the capture site after the experiments. The mean total mass of the logger and bird was 12.72 g. The capture and experimental protocols were approved by Malmö—Lund University Animal Ethics Committee (Permit Nos. 5.8.18-05926/2019 and 5.8.18-05284/2022).

Each flycatcher went through one experimental session inside their housing aviary, during which we recorded their behaviours using both a body-attached accelerometer and a stereoscopic videography system (Fig. 2). The accelerometer logger was attached to the animal over their synsacrum using a leg-loop harness [25]. The videography system consisted of two high-speed cameras (GoPro Hero 4) positioned outside the aviary and oriented such that they filmed the middle of the aviary arena at oblique angles from two sides. The cameras recorded videos at a temporal resolution of 90 frames-per-second with a spatial resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels. The two cameras were synchronized within a maximum 5 ns time lag, using custom-made sync electronics, which consisted of a ‘Bastet’ with ‘MewPro 2’ for the master camera, and a ‘MewPro Cable’ for the slave camera (Orangkucing Lab, Tokyo, Japan).

At the start of the experiment, we manually started video recording and accelerometer logging. Pied flycatchers are insectivores that catch their insect prey on the wing, by rapidly taking off from a perch, perform a catching manoeuvre and then return to the perch [26]. During the experiment, we triggered in-flight prey catching behaviour by providing the animal with a mealworm suspended from a fishing line in the middle of the region-of-interest filmed by the video system. If the bird would catch and eat the mealworm, we replaced it with a new one. Experiments and video recording continued for approximately 25 min. After each experimental session, the accelerometer logger was retrieved, and the data were downloaded.

Accelerometer and video data were synchronized by first using the times indicated by the GoPro cameras and the loggers (started at activation), followed with a more accurate synchronization based on identified activities of the birds (e.g., flight initiation after a period of inactivity). We then used the video data to categorize seven different behaviours (Table 1), including the high frequency behaviours of flying and food swallowing.

After the videography-based behaviour annotations, we used the R package ‘rabc’ [27] to develop a behaviour classification algorithm for characterizing the seven behaviour categories from the accelerometery data. For this, we used a fixed window length of 64 time steps (i.e., ~ 0.6 s duration) per behavioural segment, and we calculated 19 time domain features (i.e., mean, variance, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, range of each accelerometer axis, and ODBA from all three axes) using the function ‘calculate_feature_time’ for modelling. We excluded 15,354 segments of perching behaviour to keep the number of observations of this behaviour within the order of magnitude of the other behaviours. The model performance was evaluated by the function ‘plot_confusion_matrix’ for each behaviour category, which determined the precision rate as precision = TP/(TP + FP) and recall rate as recall = TP/(TP + FN). Here, TP, FP and FN are the number of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. With the function ‘plot_confusion_matrix’ we performed a stratified five-fold cross validation (i.e., samples were selected in the same proportion) using a supervised machine learning model—XGBoost [28]. The details of the functions and resulted machine learning classifier can be found in Yu and Klaassen [27]. To evaluate the influence of sampling frequency on performance of behaviour classification, we subsampled data from the original segments by taking every second, fourth and eighth datapoint from the original dataset, resulting in 50, 25, and 12.5 Hz as the sampling frequency of subsamples. We used the same functions and metrics to evaluate the performance of behaviour classification.

Each variable-length flight bout (i.e., from the start until the end of flight) was further annotated as either a prey catching event or a non-prey catching event. Prey catching flights were those in which the animal took off from its perch, performed an in-flight prey catching manoeuvre, and then returned to perching. This could occur when the bird caught the mealworm, when it caught a free-flying insect in the arena, or when it attempted to do so. All other flight bouts were characterized as non-catching events. Different from the fixed window length analysis on the seven behaviours (Table 1), the flight bouts had variable window lengths. Therefore, it was necessary to build another model for classification between prey catching and non-prey catching flights. We calculated a different set of 22 features of each accelerometer axis (i.e., 66 features in total) of all flight bouts by functions from the ‘tsfeatures’ R package. The details of features calculation can be found in the Additional file 1: Table S1. To evaluate the influence of sampling frequency on the classification, we performed features calculation on three datasets; the original sample frequency of 100 Hz and subsampled frequencies of around 50 Hz and 25 Hz. We excluded the calculation of features for the subsampled frequency of 12.5 Hz, because in this case some features could not be calculated on the shortest flight bouts. After features calculation, we used the function ‘select_features’ from ‘rabc’ package to select the top five most important features of each dataset for this additional flight behaviour classification. Finally, we used the function ‘plot_confusion_matrix’ to compare the results between the three datasets (100 Hz, 50 Hz and 25 Hz), based on the recalls and precisions of prey catching and non-prey catching flights.

In addition to behavioural classification, we also tested how sampling frequency affects the estimation of metrics relevant for energy expenditure. Typically, energy expenditure estimates of animals using accelerometery is modelled based on tri-axial accelerometer data amplitude [29]. For simplicity, we tested how sampling frequency affects the accuracy of accelerometer amplitude estimation in flycatchers during flight, using the z-axis accelerometer data of all flight sequences (i.e., each with 64 time steps) recorded in the aviary experiments. For this, we systematically down sampled the recorded accelerometer data by factors of two, four, and eight. This resulted in four accelerometery time series, corresponding to sample frequencies of 100 Hz (original baseline data), 50 Hz, 25 Hz and 12.5 Hz. For each series, we determined the accelerometer data amplitude estimate as \(A_{{\text{estimate}}} = \frac{1}{n}\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^n |a_z (i)|,\) where az is the z-axis accelerometer data and n is the number of data points in the set.

We then evaluated the influence of window length and sampling frequency on the signal amplitude estimation for powered flight. For this we identified the powered flight sequences with relatively consistent active wingbeat cycles by selecting z-axis accelerometer data of all flight sequences based on two criteria: (1) the primary wingbeat frequency should lay between 18 and 20 Hz [30]; (2) the standard deviation should be larger or equal to the 75% quantile of all flight sequences. The second criterion guarantees that the wave contains mostly flapping flight. We then used linear interpolation on the selected time series to expand it to a resolution of 1600 Hz as the baseline series (i.e., from the initial 64 to 1009 time steps). The first 900 time steps of each interpolated time series were used in the following test, which approximately contain ten wave cycles. We then systematically varied the window length (i.e., normalized window length W*sampling) from one to nine times the signal’s wave cycle, with 90 time steps for each cycle. The initial point of each subset was set at the start of each wave cycle, and its end point was less or equal to the end point of the wave. For example, when using nine times a wave cycle as W*sampling, two subsets were used for calculation per subsample series (i.e., one sample between wave cycles 1 to 9 and one between waves 2 and 10).

We performed this window analysis using the series with signal normalized sample frequencies f*sampling = fsampling/fsignal = 2.1 to 5, with increment of 0.1. For each of these subsets, we estimated the signal amplitude \(A_{{\text{estimate}}}\), and the normalized difference between the estimated amplitude and the baseline amplitude as ΔA* = (Aestimate-Abaseline)/Abaseline. Here, the baseline amplitude is the amplitude estimate at the maximum sampling frequency. For all combinations of sampling frequency and window length, we determined the mean value and standard deviation of the normalized amplitude difference, as they represent the accuracy and precision of the estimate, respectively.

Theoretical data simulation and analysis

We used a simulated sine wave to investigate in more detail the influence of the sampling frequency (relative to Nyquist frequency) on acquiring signal frequency and amplitude. The signal sine wave has a frequency of fsignal = 10 Hz and an amplitude Asignal = 1. The total wavelength is 800 data points (i.e., 80 datapoints for each sine wave cycle). The sine wave was denoted \(y = \sin \left( {2\pi f_{{\text{signal}}} x} \right),\,{\text{where}}\,x\,{\text{ is between 0 and 1, with}}\,\Delta x = 1/800.\) We then sampled this signal at the seven frequency levels of fsampling = 6, 11, 21, 31, 41, 51 and 61 Hz. We defined these seven cases using the signal-normalized sampling frequency, defined as f*sampling = fsampling/fsignal = 0.6, 1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 4.1, 5.1 and 6.1. To avoid signal trapping, we chose all sampling frequencies to be 1 Hz higher than the multiplication factors of the signal frequency (e.g., 11 Hz instead of 10 Hz). For example, if we had sampled at exactly 10 Hz, the resulting waves would all have constant values. For each sampling frequency, the start of the sample was set at the first quarter of the first sine wave in the signal, which resulted in 21 different commence points for each sample series.

From each sampled time series, we then determined the signal frequency estimate festimate and the signal amplitude estimate Aestimate. We calculated the frequency estimate using a fast Fourier transfer function (‘fft’ in R). To characterize the signal amplitude dynamics, we calculated the signal amplitude estimate as \(A_{{\text{estimate}}} = \frac{1}{n}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^n |x_i |\) with n as the number of datapoints.

The influence of window length and frequency on the signal amplitude estimation was evaluated using an approach similar to the one used for the flycatcher analysis. In each tested series, we systematically varied the window length (i.e., W*sampling) from one to nine times the signal’s sine wave cycle. The initial point of each subset window was set at the start of each sine wave cycle, and its end point was less or equal to the end point of the simulated sine wave. We performed this window analysis using the series with normalized sample frequencies f*sampling = 2.1–6 with increment of 0.1. For each sampling frequency, the start of the sample was set at the first quarter of the first sine wave in the signal. For each case, we estimated the normalized amplitude difference ΔA*. From each pair of subsampled frequency and window length, we determined the mean value and standard deviation of the normalized amplitude difference, as they represent the accuracy and precision of the estimate, respectively.

In accelerometer applications, the recorded data are unlikely to be pure sine waves without any noise. Therefore, we did two additional simulations to include noise and higher frequency component in the analysis. We added white noise with signal-to-noise ratio of 10 to the original simulated sine wave for the noise simulation. For the higher frequency component simulation, we added the second harmonic of the sine wave signal to the data. The amplitude of higher harmonics generally scales inversely with the square of the harmonics number [31], and thus we set the second harmonic amplitude to 1/4 of the signal amplitude. Furthermore, we added a harmonic phase shift of π/3. Thus, the resulting acceleration signal with second harmonic equals a = asignal + aharmonic2, with aharmonic2 = Aharmonic2 sin(2πfharmonic2 x + π/3), where fharmonic2 = 2 fsignal and Aharmonic2 = 1/4 Asignal. The influence of window length and frequency on the signal amplitude estimation were also tested on these two simulated waves.

Results

Accelerometery, behaviour and sampling frequency

In total, we performed aviary-based experiments with seven wild-caught pied flycatchers (i.e., one experiment for each bird), resulting in 160 min of combined video and accelerometer data. From the video recordings, we annotated 18,061 even-length segments according to seven behaviour categories. By excluding the 15,354 perching segments, 2707 segments were used in the following analysis. The seven annotated behaviours were flying (N = 1016 segments), preening (N = 94 segments), food shaking (N = 180 segments), perching (N = 1000 segments), swallowing (N = 131 segments), bill wiping (N = 39 segments), and other (N = 247 segments). Among the flight sequences (i.e., flight bouts with uneven time steps), we identified 51 flights as prey catching flights and 205 as non-catching flights. The flights had variable lengths that ranged from 25 to 388 timesteps (i.e., around 0.25–3.88 s).

Visual assessment of the down sampled data for flying and swallowing highlights interesting trends. The accelerations during flight are dominated by the wingbeat frequency of 18 ± 3.6 Hz (calculated from all z-direction accelerometer data of flying by ‘fft’ function). This signal is strongest in the y- and z-directions (ay and az), whereas sideways accelerations (ax) remain small (Fig. 3a). Subsamples at 50 Hz were above the Nyquist frequency of flying (i.e., approximately 36 Hz). The individual wave cycles due to each wing flapping cycle remained clearly distinguishable, although local maxima and minima of several cycles were missing. For sample frequencies below the Nyquist frequency of flying, at 25 and 12.5 Hz, the details of each wave cycle were lost, which is known as signal aliasing [32]. Nevertheless, the signal maxima and minima were roughly retained, but only when sampling duration is long enough.

Example time-series waveform plots for tri-axial accelerometer data (marked by ax: lateral movement, ay: longitudinal movements, and az: vertical movement) of flying (A), and swallowing behaviour (B). Grey lines are original raw data sampled at 100 Hz. Black lines are waveforms subsampled at 50, 25, and 12.5 Hz. Vertical scale bars in the 50 Hz panel of A and B show scale in number of g units (1 g = 9.8 m/s2)

For the food swallowing behaviour (Fig. 3b), the accelerations mostly occur in the y-direction (approximately aligned with the body axis), at a primary frequency of 28 ± 9.4 Hz (calculated from all y-direction accelerometer data of swallowing using the ‘fft’ function). Therefore, subsamples at 50 Hz were already below the Nyquist frequency of swallowing (~ 56 Hz), resulting in signal aliasing. Unlike for the signals from flying, the acceleration peaks (maxima and minima) for swallowing were lost for both the 25 Hz and 12.5 Hz sampling frequencies, also when the complete swallowing action was sampled.

Precision and recall values were used as the metrics to evaluate machine learning classifier performance on behaviour classification using different sampling frequencies (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the precision and recall values of flying and perching behaviours were very close on all 4 sampling frequencies (flying: recall 97.9–98.8%, precision 94.5–96.1%; perching: recall 93.1–94.2%, precision 95.5–96.6%). The other five behaviour categories (i.e., preening, food shaking, swallowing, bill wiping and other) generally show a similar trend of precision and recall values, with higher sampling frequency resulting in improved performance. This performance trend was especially prominent for food shaking and swallowing. Similarly, the classifiers performed better on prey catching flights when using high sampling frequency (Fig. 5).

The z-axis accelerometer data of all flying segments (az, N = 1016) were used for amplitude estimation (Fig. 6). Although the amplitude estimates of each subsample series were not significantly different from the raw data at 100 Hz (Paired t-test: 50 Hz, t = 0.05, p = 0.95; 25 Hz, t = − 1.19, p = 0.24; 12.5 Hz, t = − 1.91, p = 0.06), but the variation increases at lower sampling frequencies as shown by the scatter of the points, particularly in the 12.5 Hz panel (Fig. 6).

Amplitude estimations of z-axis accelerometer data of all flying segments from seven pied flycatchers. Comparison between the mean amplitude at different subsampled frequencies on the y-axis and the empirical measured amplitude (at 100 Hz) on the x-axis. The grey diagonal line in each panel shows the 1:1 ratio

Fifty-two segments of z-axis accelerometer data of all flight sequences were selected for the analysis of how the amplitude estimation is influenced by window length and frequency collectively (Fig. 7). Here, we used the mean and standard deviation of the normalized amplitude difference ΔA* (Fig. 7a, b, respectively) as estimates of the amplitude estimation accuracy and precision, respectively. The normalized mean values of ΔA* are surprisingly small, as they remain close to zero throughout almost the complete parametric space of sampling frequency and window length (Fig. 7a). Only at the lowest tested sampling frequency (~ Nyquist frequency) the mean ΔA* goes up, but only to values less than 0.03 (3% of baseline amplitude). This shows that the amplitude estimation accuracy is unbiased, even for short window lengths at sampling frequencies above the Nyquist frequency. The standard deviation of ΔA* varies much more with window length and normalized sample frequency (Fig. 7b). At sampling frequencies of more than three times the wingbeat frequency, the standard deviation is already significant, especially for low window lengths. Strikingly, at the combination of the smallest window length and lowest tested sampling frequency (~ Nyquist frequency), the standard deviation increases to half the baseline amplitude. This shows that the amplitude estimation precision is much more sensitive to the sampling frequency and window length, to the point that amplitude estimations cannot be trusted anymore. Therefore, to achieve proper amplitude estimation precision the window length should be greater than two times the signal duration, and normalized sample frequency should be larger than 3.1 (Fig. 7b).

Evaluation of the influence of normalized window length (W*sampling) and normalized sampling frequency (f*sampling) on the precision and accuracy of the amplitude estimation, of the selected z-axis accelerometer data of flying pied flycatchers. A We quantified the estimation precision using the mean of the normalized amplitude difference between signal and estimate (ΔA*). B We quantified the equivalent estimation accuracy using the standard deviation (SD) of ΔA*

Simulating and modelling of how sampling frequency affects signal estimation

A simulated sine wave with signal frequency of fsignal = 10 Hz and sampling frequency of 800 Hz was used in the simulated data analysis. Normalized sample frequency of 0.6, 1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 4.1, 5.1 and 6.1 were used. With higher sampling frequency, the waveform plots were closer to the original simulated sine wave (Fig. 8a). We can observe the signal aliasing effect at frequencies of the subsamples lower than Nyquist frequency (i.e., plots of f_0.6 and f_1.1 in Fig. 8a). Also, the main frequency of normalized samples at 0.6 and 1.1 could not match the original signal frequency at 10 Hz (Fig. 8b). With sampling frequency equal to or higher than Nyquist frequency (i.e., 2.1 and higher), the frequency information of the original signal could be retained (Fig. 8b). The amplitude estimation of each subsample series was close to the value of the original sine wave (Fig. 8c). However, the deviation increased with the decreasing of sampling frequency from 2.1 to 0.6 in Fig. 8c.

Sine wave simulations (i.e., Y = sin(X)) and the frequency and amplitude plots. A Waveforms of the original simulated sine wave (grey lines) and subsampled waveforms from 0.6 to 6.1 (annotated by f_0.6 to f_6.1) times the frequency of the original sine wave at 10 Hz. The initial points of subsample series within each frequency panel were chosen at 1, 5, 9, 13, 17, and 21 within the first quarter of the first sine wave for demonstration purpose. B Boxplot of main frequency calculated from each subsample series. The frequency of the original simulated sine wave is marked by the grey line. C Boxplot of mean amplitude calculated from each subsample series. The mean amplitude of the original simulated sine wave is marked by the grey line

Furthermore, similar to the results from the flight sequences of the pied flycatchers (Fig. 7), small normalized mean values (Fig. 9d–f) indicated the estimations of amplitude were unbiased, and the amplitude estimation from simulated data was also influenced by the window length and frequency jointly (Fig. 9g–i). With a window length between 1 to 6 and a sampling frequency close to the normalized frequency of 2.1, the amplitude estimation had large variation from the true amplitude. With higher sampling frequencies, the amplitude estimations were less influenced by window length. Compared to the original sine wave, amplitude estimation had larger variation on the sine wave with white noise added (i.e., compare Fig. 9h with Fig. 9g). Adding the second harmonic as ‘noise’ to the sine wave signal data had a stronger effect than the white noise (Fig. 9c, f, i vs. Figure 9b, e, h). The signal estimation precision was affected relatively little, but the estimation accuracy was reduced particularly close to the normalized frequency of ~ 2.8 (Fig. 9i). A similar reduction in estimation accuracy was observed for the pied flycatcher experimental data (Fig. 7b), suggesting that in both cases higher harmonics might cause this phase locked reduction in estimation accuracy.

Evaluation of the influence of normalized window length and normalized sample frequency on the precision and accuracy of the signal amplitude estimation, for simulated sine wave data with and without artificial noise added. A–C The simulated sine wave without noise added (A), with white noise (B), and with the second harmonic added as noise (C). D–I The effect of normalized sampling frequency (f*sampling) and normalized sampling window length (W*sampling) on the signal amplitude estimation. D–F We quantified the estimation precision using the mean of the normalized amplitude difference between signal and estimate (ΔA*), for the sine wave without noise, with white noise, and with the second harmonic, respectively. G–I we quantified the equivalent estimation accuracy using the standard deviation of ΔA*, for the sine wave without noise, with white noise, and with the second harmonic, respectively

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate how to apply the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem to accelerometer sampling frequency for accurate animal behaviour classification and energy expenditure estimation. In general, the performance of machine learning classifiers improved when using higher sampling frequency, especially on short-burst behaviours such as food shaking and swallowing of pied flycatchers. For detailed behaviour classification (i.e., prey catching and non-prey catching within the flying category), sampling frequencies higher than Nyquist frequency performed better. Using simulated sine wave data and accelerometer data of pied flycatchers, we demonstrated that with higher sampling frequency than the Nyquist frequency (i.e., two times Nyquist frequency) the amplitude values were better representatives of the original signal.

When using a sampling frequency higher than the Nyquist frequency for behaviour classification, more information from the original signal can be retained. For example, the swallowing behaviour was clear on the y-axis accelerometer data using 100 Hz because the sampling frequency was around 3.6 times the movement frequency of swallowing. With sampling frequency equal to and lower than 50 Hz (i.e., 1.8 times the frequency of swallowing), signal aliasing caused failure to detect details of this behaviour. Consequently, the classifiers with sampling frequencies at 50, 25, and 12.5 Hz had lower recall and precision rates than using 100 Hz. Similarly, 100 Hz was around 5 times the flapping frequency of flycatchers, which resulted in better classification performance in prey catching and non-prey catching classification than models using 50 Hz or lower (i.e., 2.5 times the frequency of flapping and lower). When performing flycatching, a bird generally had more short-burst manoeuvres, of which more information could be retained when using a high sampling frequency. Other studies also found that higher sampling frequency could improve behaviour classification model accuracy (e.g., [9, 33]). However, in some cases the improvement was limited for some behaviours (e.g., standing and lying behaviours of sheep in [18]). One possible reason was that the sampling frequency may already be more than two times the Nyquist frequency. Therefore, very limited information gain could be achieved using an even higher sampling frequency.

Although a high sampling frequency could benefit classification of short-burst movements, this was not always necessary. The choice of sampling frequency depends on the aim of the study. In this study, we demonstrated that even with 12.5 Hz sampling frequency the classification of flying and perching remained at high precision and recall values, although 12.5 Hz was much lower than the Nyquist frequency of flying pied flycatchers. Assuming we combined behaviours other than flying and perching (i.e., preening, food shaking, swallowing, bill wiping and other) into one category of “active behaviours”, the behaviour classification model for the three categories would have had good performance of all categories, which has already been applied in studies tracking songbirds for long-term research using on-board accelerometer data reductions (e.g., [34,35,36,37]). Because flying has high intensity and perching has almost zero intensity, the data could retain the relatively high and low intensity information even with sampling frequency lower than the Nyquist frequency.

The simulated data at Nyquist frequency could retain the frequency information well (Fig. 8b). Higher sampling frequency than the Nyquist frequency (i.e., two times Nyquist frequency) also retained the amplitude information well, either for mean amplitude across multiple movement cycles or the amplitude information of each movement cycle. In this study, the swallowing behaviours of pied flycatchers were short burst (Fig. 3b). These behaviours are similar to the simulated sine wave case with normalized window lengths close to one (Fig. 9). The simulations without and with 10% white noise added to the signal (Fig. 9a, d, g and Fig. 9b, e, h, respectively) suggest that a normalized frequency of at least 2.8 (i.e., 1.4 times Nyquist frequency) should be chosen to guarantee stable amplitude estimation. The results of the simulations with the second harmonic included in the signal (Fig. 9c, f, i) suggest that the normalized frequency should be even higher, especially when proper estimation accuracy is needed (Fig. 9i).

The amplitude information was important for behavioural and energetic studies of short-burst behaviours such as “pounce-buck” of pumas [38] or feeding and escape activities of the great sculpin [9]. In other cases, both frequency and amplitude information were necessary for capturing wingbeat kinematics and estimating power required to fly [20]. Also, higher sampling frequency could result in more accurate amplitude estimation, which was shown by a lower scatter condition of the experimental data and low range around true mean value of the simulated data.

The effect of window length on the calculation of mean amplitude with different sampling frequencies indicated that if the window length was long (i.e., > 10 movement cycles), lower sampling frequency could yield similar mean amplitude values as the ones with high sampling frequency. This effect could explain the findings by Halsey et al. [10] that with a 5-min window for ODBA calculation, even sampling frequency as low as 0.2 Hz could remain at a similar level as the ones calculated from 10 Hz. One should be cautious when using accelerometers to study wild animals since many species have variable behaviours within short time intervals. The choice of sampling frequency and time window for energy expenditure approximation should be carefully adjusted to suit different study species and purposes.

In addition, there was a difference between the experimental data (Fig. 7b) and simulated data (Fig. 9g) around the normalized sample frequency of 2.8, where the deviations of amplitude estimation were large on experimental data with short window length. However, when adding a second harmonic to the simulated signal, the high variation also appeared around the normalized sample frequency of 2.8 (Fig. 9i). Our spectral analysis of z-axis flight accelerometer data indicated that a similar second harmonic is also present in most flight data (Additional file 2: Fig. S1). Similar waveform patterns could also be found on the accelerometer measurement of pigeon flight [20]. The large variation around normalized sample frequency of 2.8 was probably caused by signal aliasing effect of the high frequency component. This suggested that a choice of high sampling frequency (i.e., two times Nyquist frequency) could well mitigate the aliasing effect.

The drawbacks of choosing a high sampling frequency of an accelerometer are high battery energy consumption and high storage requirement, which would both limit the duration of sampling. To reduce energy consumption and hence battery lifespan, one strategy is to use adaptive sampling settings, where high sampling frequency would only be used for high frequency movements when necessary (e.g., [39]), while sample frequency is reduced when the animal is inactive. To reduce the storage, on-board data processing can reduce data volume for longer measurement periods, either by processing of raw accelerometer data into representative features (e.g., [40]) or by applying a machine learning classifier directly on-board (e.g., [41]). In addition, for new study species without prior knowledge of the movement frequencies of different behaviours, a pilot study using a high sampling frequency would be necessary for the exploration of the full potentials using accelerometery.

Concluding remarks

Based on the analyses and findings from this study, we give three recommendations for different study objectives. First, in biologging devices with no memory and battery constraints, we recommend using at least two times Nyquist frequency to achieve relative optimal representation of signal information (i.e., frequency and amplitude). In addition, this choice will mitigate the influence of unexpected high frequency signals, which could be twice the movement frequency of behaviours (e.g., flying in this study). Second, for classification and energy expenditure estimation of short-burst behaviours, 1.4 times the Nyquist frequency of behaviour is required. Third, in studies only interested in energy expenditure approximations using accelerometer data, we suggest using at least the Nyquist frequency of the movement frequency of the behaviour for a stable calculation of the signal amplitude.

Availability of data and materials

Annotated accelerometer data used in this study are available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23659578.

References

Williams HJ, Taylor LA, Benhamou S, Bijleveld AI, Clay TA, de Grissac S, Demsar U, English HM, Franconi N, Gomez-Laich A, Griffiths RC, Kay WP, Morales JM, Potts JR, Rogerson KF, Rutz C, Spelt A, Trevail AM, Wilson RP, Borger L. Optimizing the use of biologgers for movement ecology research. J Anim Ecol. 2020;89:186–206.

Wilmers CC, Nickel B, Bryce CM, Smith JA, Wheat RE, Yovovich V. The golden age of bio-logging: how animal-borne sensors are advancing the frontiers of ecology. Ecology. 2015;96:1741–53.

Nathan R, Monk CT, Arlinghaus R, Adam T, Alos J, Assaf M, Baktoft H, Beardsworth CE, Bertram MG, Bijleveld AI, Brodin T, Brooks JL, Campos-Candela A, Cooke SJ, Gjelland KO, Gupte PR, Harel R, Hellstrom G, Jeltsch F, Killen SS, Klefoth T, Langrock R, Lennox RJ, Lourie E, Madden JR, Orchan Y, Pauwels IS, Riha M, Roeleke M, Schlagel UE, Shohami D, Signer J, Toledo S, Vilk O, Westrelin S, Whiteside MA, Jaric I. Big-data approaches lead to an increased understanding of the ecology of animal movement. Science. 2022;375:eabg1780.

Williams HJ, Shipley JR, Rutz C, Wikelski M, Wilkes M, Hawkes LA. Future trends in measuring physiology in free-living animals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021;376:20200230.

Yu H, Deng J, Nathan R, Kroschel M, Pekarsky S, Li G, Klaassen M. An evaluation of machine learning classifiers for next-generation, continuous-ethogram smart trackers. Mov Ecol. 2021;9:15.

Brown DD, Kays R, Wikelski M, Wilson R, Klimley AP. Observing the unwatchable through acceleration logging of animal behavior. Animal Biotelemetry. 2013;1:20.

Liechti F, Bauer S, Dhanjal-Adams KL, Emmenegger T, Zehtindjiev P, Hahn S. Miniaturized multi-sensor loggers provide new insight into year-round flight behaviour of small trans-Sahara avian migrants. Mov Ecol. 2018;6:19.

Goldbogen JA, Stimpert AK, Deruiter SL, Calambokidis J, Friedlaender AS, Schorr GS, Moretti DJ, Tyack PL, Southall BL. Using accelerometers to determine the calling behavior of tagged baleen whales. J Exp Biol. 2014;217:2449–55.

Broell F, Noda T, Wright S, Domenici P, Steffensen JF, Auclair JP, Taggart CT. Acceleroget almeter tags: detecting and identifying activities in fish and the effect of sampling frequency. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:1255–64.

Halsey LG, Green JA, Wilson RP, Frappell PB. Accelerometry to estimate energy expenditure during activity: best practice with data loggers. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2009;82:396–404.

Garde B, Wilson RP, Fell A, Cole N, Tatayah V, Holton MD, Rose KAR, Metcalfe RS, Robotka H, Wikelski M, Tremblay F, Whelan S, Elliott KH, Shepard ELC. Ecological inference using data from accelerometers needs careful protocols. Methods Ecol Evol. 2022;2022:1.

Kölzsch A, Neefjes M, Barkway J, Müskens GJDM, van Langevelde F, de Boer WF, Prins HHT, Cresswell BH, Nolet BA. Neckband or backpack? Differences in tag design and their effects on GPS/accelerometer tracking results in large waterbirds. Animal Biotelemetry. 2016;4:13.

Ladds MA, Thompson AP, Kadar J-P, Slip J, Hocking DP, Harcourt RG. Super machine learning: improving accuracy and reducing variance of behaviour classification from accelerometry. Animal Biotelemetry. 2017;5:8.

Shepard ELC, Wilson RP, Halsey LG, Quintana F, Gómez Laich A, Gleiss AC, Liebsch N, Myers AE, Norman B. Derivation of body motion via appropriate smoothing of acceleration data. Aquat Biol. 2008;4:235–41.

Khan A, Hammerla N, Mellor S, Plötz T. Optimising sampling rates for accelerometer-based human activity recognition. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2016;73:33–40.

Lok T, van der Geest M, Bom RA, de Goeij P, Piersma T, Bouten W. Prey ingestion rates revealed by back-mounted accelerometers in Eurasian spoonbills. Animal Biotelemetry. 2023;11:1.

Hounslow JL, Brewster LR, Lear KO, Guttridge TL, Daly R, Whitney NM, Gleiss AC. Assessing the effects of sampling frequency on behavioural classification of accelerometer data. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2019;512:22–30.

Walton E, Casey C, Mitsch J, Vazquez-Diosdado JA, Yan J, Dottorini T, Ellis KA, Winterlich A, Kaler J. Evaluation of sampling frequency, window size and sensor position for classification of sheep behaviour. R Soc Open Sci. 2018;5:171442.

Qasem L, Cardew A, Wilson A, Griffiths I, Halsey LG, Shepard ELC, Gleiss AC, Wilson R. Tri-axial dynamic acceleration as a proxy for animal energy expenditure; should we be summing values or calculating the vector? PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31187.

Krishnan K, Garde B, Bennison A, Cole NC, Cole EL, Darby J, Elliott KH, Fell A, Gomez-Laich A, de Grissac S, Jessopp M, Lempidakis E, Mizutani Y, Prudor A, Quetting M, Quintana F, Robotka H, Roulin A, Ryan PG, Schalcher K, Schoombie S, Tatayah V, Tremblay F, Weimerskirch H, Whelan S, Wikelski M, Yoda K, Hedenstrom A, Shepard ELC. The role of wingbeat frequency and amplitude in flight power. J R Soc Interface. 2022;19:20220168.

Shannon CE. Communication in the presence of noise. Proc IRE. 1949;37:10–21.

Chen KY, Bassett DR Jr. The technology of accelerometry-based activity monitors: current and future. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:S490-500.

Nathan R, Spiegel O, Fortmann-Roe S, Harel R, Wikelski M, Getz WM. Using tri-axial acceleration data to identify behavioral modes of free-ranging animals: general concepts and tools illustrated for griffon vultures. J Exp Biol. 2012;215:986–96.

Tatler J, Cassey P, Prowse TAA. High accuracy at low frequency: detailed behavioural classification from accelerometer data. J Exp Biol. 2018;221:jeb184085.

Rappole JH, Tipton AR. New harness design for attachment of radio transmitters to small passerines (Nuevo Diseño de Arnés para Atar Transmisores a Passeriformes Pequeños). J Field Ornithol. 1991;62:335–7.

Bibby CJ, Green RE. Foraging behaviour of migrant pied flycatchers, ficedula hypoleuca, on temporary territories. J Anim Ecol. 1980;49:507–21.

Yu H, Klaassen M. R package for animal behavior classification from accelerometer data—rabc. Ecol Evol. 2021;11:12364–77.

Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining; 2016. p. 785–94.

Wilson RP, White CR, Quintana F, Halsey LG, Liebsch N, Martin GR, Butler PJ. Moving towards acceleration for estimates of activity-specific metabolic rate in free-living animals: the case of the cormorant. J Anim Ecol. 2006;75:1081–90.

Tomotani BM, Muijres FT, Koelman J, Casagrande S, Visser ME, Portugal S. Simulated moult reduces flight performance but overlap with breeding does not affect breeding success in a long-distance migrant. Funct Ecol. 2017;32:389–401.

Hwang Y, Cossu C. Linear non-normal energy amplification of harmonic and stochastic forcing in the turbulent channel flow. J Fluid Mech. 2010;664:51–73.

Mitchell DP, Netravali AN. Reconstruction filters in computer-graphics. SIGGRAPH Comput Graph. 1988;22:221–8.

Brownscombe JW, Lennox RJ, Danylchuk AJ, Cooke SJ. Estimating fish swimming metrics and metabolic rates with accelerometers: the influence of sampling frequency. J Fish Biol. 2018;93:207–14.

Bäckman J, Andersson A, Pedersen L, Sjöberg S, Tøttrup AP, Alerstam T. Actogram analysis of free-flying migratory birds: new perspectives based on acceleration logging. J Comp Physiol A. 2017;203:543–64.

Evens R, Kowalczyk C, Norevik G, Ulenaers E, Davaasuren B, Bayargur S, Artois T, Akesson S, Hedenstrom A, Liechti F, Valcu M, Kempenaers B. Lunar synchronization of daily activity patterns in a crepuscular avian insectivore. Ecol Evol. 2020;10:7106–16.

Hedenstrom A, Norevik G, Warfvinge K, Andersson A, Backman J, Akesson S. Annual 10-month aerial life phase in the common swift apus apus. Curr Biol. 2016;26:3066–70.

Norevik G, Akesson S, Andersson A, Backman J, Hedenstrom A. The lunar cycle drives migration of a nocturnal bird. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000456.

Williams TM, Wolfe L, Davis T, Kendall T, Richter B, Wang Y, Bryce C, Elkaim GH, Wilmers CC. Instantaneous energetics of puma kills reveal advantage of felid sneak attacks. Science. 2014;346:81–5.

Wilson AM, Lowe JC, Roskilly K, Hudson PE, Golabek KA, McNutt JW. Locomotion dynamics of hunting in wild cheetahs. Nature. 2013;498:185–9.

Nuijten RJM, Gerrits T, Shamoun-Baranes J, Nolet BA. Less is more: on-board lossy compression of accelerometer data increases biologging capacity. J Anim Ecol. 2020;89:237–47.

Yu H, Deng J, Leen T, Li G, Klaassen M. Continuous on-board behaviour classification using accelerometry: a case study with a new GPS-3G-Bluetooth system in Pacific black ducks. Methods Ecol Evol. 2022;13:1429–35.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Arne Andersson and Johan Bäckman for developing the micro data loggers used in this study and for setting them up before measurements and downloading data from them after. We thank Koosje Lamers for catching the experimental pied flycatchers on the field site. We are grateful to Henjo de Knegt for providing valuable suggestions in the early stage of this work. This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council (2018-04292) to P.H., and (2016-03625, 2020-03707) to A.H., and the Next Level Animal Sciences innovation initiative of Wageningen University & Research to H.Y. and F.M. The development of the micro data loggers was possible through a Linnaeus grant from the Swedish Research Council (349-2007-8690) and Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HY, FM, AH, and PH conceived the ideas, HY, FM, JSL, and PH designed methodology; HY, JSL, and PH did experiments and collected the data; HY analyzed the data with advice from FM; HY wrote the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to writing the manuscript and gave approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Feature calculations for prey catching and non-prey catching behaviour classification through pied flycatcher accelerometer data.

Additional file 2.

An example of z-axis flight accelerometer data and spectrogram.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Muijres, F.T., te Lindert, J.S. et al. Accelerometer sampling requirements for animal behaviour classification and estimation of energy expenditure. Anim Biotelemetry 11, 28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-023-00339-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-023-00339-w