Abstract

Background

Future distribution of dengue risk is usually predicted based on predicted climate changes using general circulation models (GCMs). However, it is difficult to validate the GCM results and assess the uncertainty of the predictions. The observed changes in climate may be very different from the GCM results. We aim to utilize trends in observed climate dynamics to predict future risks of Aedes albopictus in China.

Methods

We collected Ae. albopictus surveillance data and observed climate records from 80 meteorological stations from 1970 to 2021. We analyzed the trends in climate change in China and made predictions on future climate for the years 2050 and 2080 based on trend analyses. We analyzed the relationship between climatic variables and the prevalence of Ae. albopictus in different months/seasons. We built a classification tree model (based on the average of 999 runs of classification and regression tree analyses) to predict the monthly/seasonal Ae. albopictus distribution based on the average climate from 1970 to 2000 and assessed the contributions of different climatic variables to the Ae. albopictus distribution. Using these models, we projected the future distributions of Ae. albopictus for 2050 and 2080.

Results

The study included Ae. albopictus surveillance from 259 sites in China found that winter to early spring (November–February) temperatures were strongly correlated with Ae. albopictus prevalence (prediction accuracy ranges 93.0–98.8%)—the higher the temperature the higher the prevalence, while precipitation in summer (June–September) was important predictor for Ae. albopictus prevalence. The machine learning tree models predicted the current prevalence of Ae. albopictus with high levels of agreement (accuracy > 90% and Kappa agreement > 80% for all 12 months). Overall, winter temperature contributed the most to Ae. albopictus distribution, followed by summer precipitation. An increase in temperature was observed from 1970 to 2021 in most places in China, and annual change rates varied substantially from -0.22 ºC/year to 0.58 ºC/year among sites, with the largest increase in temperature occurring from February to April (an annual increase of 1.4–4.7 ºC in monthly mean, 0.6–4.0 ºC in monthly minimum, and 1.3–4.3 ºC in monthly maximum temperature) and the smallest in November and December. Temperature increases were lower in the tropics/subtropics (1.5–2.3 ºC from February–April) compared to the high-latitude areas (2.6–4.6 ºC from February–April). The projected temperatures in 2050 and 2080 by this study were approximately 1–1.5 °C higher than those projected by GCMs. The estimated current Ae. albopictus risk distribution had a northern boundary of north-central China and the southern edge of northeastern China, with a risk period of June–September. The projected future Ae. albopictus risks in 2050 and 2080 cover nearly all of China, with an expanded risk period of April–October. The current at-risk population was estimated to be 960 million and the future at-risk population was projected to be 1.2 billion.

Conclusions

The magnitude of climate change in China is likely to surpass GCM predictions. Future dengue risks will expand to cover nearly all of China if current climate trends continue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dengue is a viral infection transmitted to humans through the bite of infected female Aedes mosquitoes [1]. Dengue is becoming an increasing global public health threat, not only because no vaccine or effective treatment exists for the disease, but also because of its unpredictable epidemics and its dramatic geographic expansion worldwide due to the aggressive global invasion of the vector Aedes albopictus [2,3,4,5,6]. The WHO reported 5.2 million dengue cases in 2019, the largest number ever reported globally, compared to about 0.5 million in 2000 and 2.4 million in 2010. Asia represents approximately 70% of the global burden of the disease [1]. The estimated at-risk population was 3.9 billion in 2010, and risk exists in 129 countries [7,8,9].

In China, the first dengue outbreak, which was also the first report of dengue, since World War II occurred in 1978 in the southern city of Foshan, Guangdong Province [10]. Before 2000, dengue outbreaks in China were concentrated in a small tropical area in the southern coastal region [11,12,13,14]. Prior to 2010, dengue outbreaks moved slowly northward along the southeastern coast [15, 16]; since 2010, however, outbreaks have soared, and in 2013, the wavefront moved to central China [12, 13, 17, 18]. The largest number of outbreaks, in terms of outbreak areas covered, occurred in 2019 and spanned 15 provinces, including Shandong Province in northern China [19,20,21]. Early dengue outbreaks were likely initiated by internationally imported infections [11, 20]; however, molecular analyses and index case tracking indicate that most recent outbreaks in central and northern China have been caused by domestic travelers returning from dengue-endemic regions of southern China [18, 22, 23]. Although Aedes aegypti is believed to be the primary dengue virus vector globally and was responsible for most of the dengue outbreaks in southern China before 2000 [24,25,26,27], recent dengue outbreaks in China have been caused almost exclusively by Ae. albopictus [28, 29]. In fact, in recent years Ae. aegypti has been found only in a few small spots in southern and southwestern China [30, 31], whereas Ae. albopictus is found all over China, including in all mild temperate regions in northern China [32, 33].

At the same time, there is a strong link between dengue outbreaks and climatic variability [34,35,36,37,38], since the development and survival of Aedes mosquitoes and virus replication depend on environmental, especially climatic, conditions [39,40,41,42]. Many studies have modeled the impact of climate change on the future potential regional and global expansion and distribution of dengue virus transmission risk [40, 41, 43, 44]. Nonetheless, dengue outbreaks have expanded into temperate northern China. Global climate change is real, as observed in the past 50 years, and climate change may accelerate the northward expansion of dengue outbreaks in China. However, nearly all dengue risk assessment modeling has used future climate projections from climate models, also known as the General Circulation Models (GCMs)[40, 41, 43,44,45,46]. There are different GCMs based on different assumptions, and they produce quite different results [47]. In addition, there are different emissions scenarios [47]. However, uncertainty due to GCMs is rarely assessed, and predicted results may not be validated. A recent study showed that from 1979 to 2021, the Arctic warmed nearly four times faster than the climate model predicted, and the magnitude of temperature increase depended on latitude, indicating that GCMs may severely underestimate global warming [48]. Since we have many years of observational data from meteorological stations across the globe, it would be interesting if not preferable to use real data to make future climate predictions and dengue risk assessments because the results can be tested or validated using currently available observed data [49]. Using observed climatic records has additional advantages. For example, climate changes vary in different regions [48, 49]; temperature increases in the tropics may have a limited impact on dengue risks in these areas, whereas temperature increases in high-latitude temperate zones may push the vector distribution boundary farther north [33, 40, 41, 49], resulting in a major impact on the expansion of the Aedes distribution and dengue risk. Using observed climatic data can lead to more accurate estimates of the spatial distribution of climate trends. However, few if any studies have attempted to use real climatic records to assess future dengue risks caused by global climate change [49].

In this study, we analyzed the relationships between the prevalence of Aedes mosquitoes and climatic variables in China. We examined the climate trends from 1970 to 2021 based on meteorological observations across China and mapped the spatial variation of these climate trends. Based on these trend analyses, we predicted the potential future climate conditions and Ae. albopictus risks in China. Dengue risk seasonality and at-risk populations were also estimated. This study provides an alternative look at the impact of climate change on dengue risk from a different angle.

Materials and methods

Aedes mosquito data collection

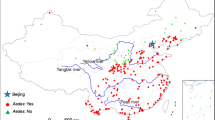

We employed the Aedes mosquito collection database established in our previous study [33]. The prevalence of Aedes at a site was defined as a place where Aedes mosquitoes have been detected. We updated the database by reviewing some recently published work [28, 29, 50,51,52]. The updated Aedes mosquito records included data up to 2021 and covered all provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in China except Taiwan Province (Fig. 1). The new China CDC Aedes surveillance system covers 23 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities, plus published data from surveillances conducted by provincial CDCs [29, 32, 54]. Most of the surveillances is performed in areas where Aedes data are already available, especially in southern China. However, there are several newly Aedes-invaded places, especially at high altitude of western Sichuan Province (Ae. albopictus) and central Qinghai Province (Aedes caspius and Aedes flavidorsalis) (Fig. 1). Surveillance sites have also been updated in Tibet Autonomous Region, however, no Aedes has been detected in the area (Fig. 1). In this study, we used data for Ae. albopictus only; other Aedes mosquitoes were not included [54,55,56]..

Many places in southern China have more than one Ae. albopictus records, to avoid redundancy, much of the sampling data from southern China was not included, since Ae. albopictus exists everywhere there (Fig. 1). Most of the surveillance results from northern China, especially from areas along the Ae. albopictus distribution boundary, were included in the modeling process so that the risk models could identify the environmental/climatic variables that could differentiate mosquito presence/absence sites. A few Ae. albopictus present localities are on the eastern slope of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, where the elevation is > 3000 m above sea level (Fig. 1). Although other mosquitoes such as Culex, Anopheles, and other Aedes mosquito species such as Ae. caspius and Ae. flavidorsalis have been found in the central area of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Ae. albopictus has not been detected there (Fig. 1). The study included Ae. albopictus data from 259 sites for analyses (Fig. 1).

Environmental and climatic suitability modeling

We updated the machine learning classification and regression tree (CART) model based on the updated Aedes database and WorldClim 2.0 data [33, 57]. Details of the climatic and environmental data have been described in our previous study [33]. In brief, the 1970–2000 average monthly climate data for the minimum, mean, and maximum temperature and precipitation were downloaded from WorldClim version 2.1 (https://www.worldclim.org/data/worldclim21.html). The environmental regions were divided into four categories: humid, sub-humid, semiarid, and arid [33]. Climatic zones comprised nine categories: south subtropical, mid-subtropical, north subtropical, warm temperate, mild temperate, cool temperate, plateau subtropical, plateau temperate, and plateau subfrigid [33].

We conducted univariate analyses to examine the relationship between Ae. albopictus prevalence and climatic variables using Chi-square automatic interaction detection (CHAID) [58, 59]. The aim was to examine how changes in climatic variables affected the presence/absence of Ae. albopictus. CHAID is similar to logistic analysis, but CHAID produces the critical cutoff of predictors and allows for a nonlinear combination of predictors [60]. In addition to overall prediction accuracy, we measured sensitivity and specificity to examine the prediction skewness (bias for presence/absence) and used Yale’s coefficient to measure the association between the observed and predicted prevalence of Ae. albopictus by each climatic variable [61, 62]. We did not examine the impact of summer temperatures (June–September) on Ae. albopictus prevalence, and we only examined the climatic effect for the same month and the following four months.

For the multivariate analysis, the detailed multi-step modeling process has been described in our previous study [33]. Briefly, after data pre-processing, CART models were developed using a tenfold cross-validation method to predict the potential seasonal (or monthly) distribution ranges of Ae. albopictus in China at a high resolution based on environmental-climatic conditions (refer to Additional file 6: Supplement A for modeling details). Since Ae. albopictus was found only in northern China from June to September, these months were aggregated as one season for risk analyses. Environmental-climatic suitability for Ae. albopictus was predicted as the average predicted suitability probability of the 10 models developed during the tenfold cross-validation modeling process, and the spatial resolution was 30 arcsec or approximately 1 km.

Model performance was measured using prediction accuracy, sensitivity (presence predicted as presence), specificity (absence predicted as absence), and Cohen’s Kappa coefficient [63]. Kappa measures the reliability of agreement between observed and predicted qualitative data and considers the possibility of the agreement occurring by chance.

Trends in climate change in China, 1970–2021

To examine the heterogeneity of climate trends in China, we collected daily meteorological records from 1970 to 2021 from 90 meteorological stations (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Since Aedes mosquitoes exist nearly everywhere in southern China except the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, we selected only a representative subset of stations for climate trend analysis. We selected as many stations as possible from northern China, especially near the current margin of the Aedes distribution [33], but excluded some stations to avoid oversampling; i.e., if two stations were located very close to each other (< 200 km) we selected only one of the two stations. Daily records were summarized as monthly maximum/minimum/mean temperatures and monthly cumulative precipitation. Trends in monthly data at each station were analyzed using linear regression analysis. Climate trends were measured as the annual change rates in monthly maximum/minimum/mean temperature and annual cumulative precipitation. Due to the large variation in monthly precipitation in different years, trends in monthly precipitation were not analyzed. Climate change trends in China were analyzed by month (temperature) or annually (precipitation) and aggregated based on latitude.

Climate change and its impact on Aedes distribution

To predict future climate distribution, we needed to create a climate trend map of China. Based on our climate trend analyses, we produced the trend distribution map using the geostatistical spatial interpolation method of universal kriging (refer to Additional file 6: Supplement B for modeling details) [64], which assumes a third-order polynomial trend model, i.e., trends in climate change may be linearly or nonlinearly correlated with latitude/longitude. Using this climate trend map and the 1970–2000 mean climate as the baseline, we predicted the temperature and precipitation distributions in China for 2020, 2050 and 2080, a typical risk projection framework [40, 41]. We compared the projected temperature increases in 2050 and 2080 between this study and the GCMs using 2000 as the baseline [41].

We used the suitability models established earlier to predict the Aedes distribution in each month based on the 2020, 2050 and 2080 climatic projections. Ae. albopictus risk was measured as the probability of presence of Ae. albopictus.

We estimated the at-risk population for different projections based on 2010 census data for each county in China and the 2020 total population [65]. Since there was no updated population distribution for 2020, we projected the 2020 population distribution to be the same as that in 2010. Because projecting the 2050 and 2080 total populations and population distributions would create additional uncertainty, i.e., we do not know the future population movement and growth across China, we used the 2020 total population as the base population and fixed it for 2050 and 2080. We were aware of the potential bias for estimating the future at-risk population based on the 2020 population, but this was the best method upon which we could rely. If the total population decreases by 2050 and 2080, the at-risk population will need to be adjusted accordingly.

All data analyses were conducted using R 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) except universal kriging, which was performed using ArcGIS Pro 3.0.0 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). The following R packages were used in this study: for raster image reading and risk mapping, we used the raster and crop methods within the rasterImage and sp packages; and for regression tree modeling, we used the ctree and rpart methods within the rpart, party, and caret packages.

Results

The impact of climatic variables on Ae. albopictus prevalence in China

Univariate analyses revealed that wintertime (November–February) mean and maximum temperature were strongly correlated with Ae. albopictus presence in the following three months (Yale’s correlation coefficient ranged from 0.84 to 1.00). October mean and maximum temperature were also important predictors of Ae. albopictus presence (Yale’s R 0.56–0.94) (Table 1); the results indicated that the higher the temperature was, the higher the prevalence (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). The minimum temperature was moderately associated with Ae. albopictus prevalence (Yale’s R 0.15–0.95) (Table 1; Additional file 2: Fig. S2). Precipitation was moderately correlated with Ae. albopictus prevalence during April–September (Yale’s R 0.15–0.91) (Table 1; Additional file 2: Fig. S2).

Aedes albopictus distribution modeling

Multivariable modeling with tenfold cross-validation indicated that the models predicted the existing Ae. albopictus sites with very high accuracy (Fig. 2). The accuracy of the predictions ranged from 93.2% in May to 99.2% in February. Kappa agreement between observed and predicted Aedes prevalence ranged from 0.78 for June–September to 0.98 in February indicating almost perfect agreement (> 0.80 considered perfect). Sensitivity ranged from 94.6% (November) to 100% (February), and specificity ranged from 81.8% (May) to 100% (January) (Fig. 2).

Variable importance analyses found that winter to early spring (October–February) temperature were the most important factors that determined the presence of Ae. albopictus, and the relative influences of each variable on Ae. albopictus presence were very similar from December to March (ranging from 15 to 20%) (Table 2). A greater number of variables influenced the Ae. albopictus distribution from April to November and environmental/climatic zones were only important for determining June–October Ae. albopictus distribution (Table 2). The overall total influence of climatic variable in each month varied from no influence to 82% (Table 3). October to February temperatures contributed the most (range 19–82%, mean ± standard deviation (SD): 44.3 ± 20.5%), followed by summertime (June–September) precipitation (range 10–15%, mean 12.8 ± 2.2%) (Table 3).

Climate changes from 1970 to 2021

We analyzed changes in monthly temperature and annual precipitation for the study period. We found that in general, temperature increases were more pronounced in central and northern China than in the southern subtropical areas and were greater in spring (February–April) than in winter (October–December) (Fig. 3). The minimum temperature increased the most, approximately 3–4 °C, in high-latitude areas in the north in March, while the maximum temperature increased by 3–4 °C across central China from February to March. The greatest increase in the mean temperature (4.7 °C in March) was similar to that of the maximum temperature (4.3 °C in March) but was more pronounced in the north (Fig. 3). For example, the average increase in the maximum temperature in March was 3.5 °C in the north > 39°N and 4.1 °C in the south-central 28–39°N, whereas mean temperature in March increased 4.5 °C in the north > 36°N and 3.5 °C in the south-central 28–36°N (Fig. 3). The winter temperature increase was minimal (Fig. 3). In most places and months, the temperature increased by approximately 1–2 °C (Fig. 3); however, inter-station variation was large (Additional file 3: Fig. S3). For example, in Ejin Qi of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, north of the current Ae. albopictus northern boundary, the minimum temperature increased at least 3 °C in almost all months and more than 5 °C in two months (Additional file 3: Fig. S3a), while in Datong in Shanxi Province, which lies just on the Ae. albopictus distribution northern boundary line, the minimum temperature decreased by approximately 2 °C in several months (Additional file 3: Fig. S3a). Overall, the normalized (anomaly) mean temperature showed very similar trends in central, western and northern China, i.e., north of (including) Xuzhou (Jiangsu Province), Zhengzhou (Henan Province), and Xi’an (Shannxi Province) cities, plus Gansu, Xinjiang and Tibet Province/Autonomous Regions (Fig. 4a), while a few stations in southern China showed almost no change in the mean temperature from 1970 to 2021 (Fig. 4b). The major changes in the mean temperature started in 1990, i.e., the mean temperature was below normal before 1990 and above normal after 1990 (Fig. 4c, d). The trends were very similar for southern (mean increase of 0.0432 °C/year, R2 = 0.72) and northern (mean increase of 0.0436 °C/year, R2 = 0.71) China (Fig. 4c, d).

Monthly precipitation varied greatly, and we did not find consistent trends (results not shown). However, analysis of annual precipitation found that overall precipitation increased > 100 mm during the study period in most regions (Fig. 3d). Similar to temperature, trends in precipitation varied greatly among stations (Additional file 3: Fig. S3b). For example, in Beijing, although annual precipitation increased in the past two decades, the overall change in precipitation from 1970 to 2021 was nearly zero (annual change rate − 0.162 mm); however, in many other places, precipitation increased considerably in the past 10 years (Additional file 3: Fig. S3b).

Projection of future climatic conditions and distribution of Ae. albopictus

Despite variations, the observed annual temperature anomaly showed a clear linear increase from 1970 to 2021 (Temperature = 0.0434, Year–86.146, R2 = 0.71) (Fig. 4). Based on the linear regression model, we predicted that the mean temperature will increase approximately 2.17 °C (range 1.88–2.46 °C) in China by 2050 from the 2000 baseline, compared to the GCM prediction of 0.98–1.36 °C increase globally by 2050 [47], i.e., GCMs underestimated approximately 1 °C increase in temperature. Similarly, we predicted a 3.47 °C (range 3.10–3.93 °C) increase in the mean temperature by 2080 based on meteorological observations, while GCMs predicted 1.06–2.39 °C increase by 2080 [47].

Figure 4 shows the estimated baseline (2000) distribution of the Ae. albopictus in China, the updated current distribution (2020), and the projected distributions for 2050 and 2080 based on predicted climate changes (Additional file 4: Fig. S4, Additional file 5: Fig. S5). The major changes in the Ae. albopictus distribution from 2000 to 2020 were the slight expansion in north-central and northeastern China in April and May (Fig. 5a, b). However, major changes in the Ae. albopictus distribution were projected for April–November by 2050 and 2080 (Fig. 5c, d). Currently, Ae. albopictus distribution is limited to north-central and a small portion of northeastern China; by 2050, if the current trend in climate change continues, Ae. albopictus may be found in most parts of northern China, mostly in the summer (June–September) and possibly in April, May, and October (Fig. 5c, d). Expansion in the Ae. albopictus distribution in the winter (December–February) was limited, even for 2050 and 2080 (Fig. 5c, d).

After consideration of the conditions for vector development and dengue virus growth (replication), and in consideration of current dengue outbreak areas in China, we estimated a population of approximately 960 million at risk of Ae. albopictus in 2020. Based on the 2020 total population in China and the population distribution from the 2010 census, we estimated that the at-risk population will increase to approximately 1.2 billion by 2050, with 1.02 billion at high risk (risk probability > 0.5), which covers south China to the west up to Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, to the north up to southern parts of Hebei, Shanxi and Shannxi provinces, and an additional 180 million at moderate to low risk (risk probability ≤ 0.5), which includes a small part of southern Gansu Province, northern parts of Shanxi and Hebei provinces, Liaoning Province and southeastern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Fig. 5). The risk maps for 2080 are similar to those for 2050 (Fig. 5). We must note that our estimates of the at-risk population were based on current census data (2010 distribution and 2020 total population) and did not include possible future increases/decreases in total population or changes in the population distribution.

Discussion

Many studies have predicted future distributions of Aedes mosquitoes and risks of dengue, including regional- and global-level predictions, based on GCMs of different climate change scenarios [40, 41, 43,44,45,46]. Since different models yield quite different results, it is difficult to assess the uncertainty of the predictions and to validate the modeling results. A study of climate change in the Arctic found that the actual increase in temperature from 1979 to 2021 was 4 times of that predicted by climate model [48], indicating the uncertainty of GCM predictions and the importance of observational data. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use actual observed climate trends to predict the future distribution of dengue risks worldwide. We found strong trends (measured by linear regression and correlation coefficient) in climate warming across nearly all meteorological observations in China, which makes our climate change predictions reliable if the current trend holds; the fixed annual change rates are similar to the assumptions for the climate models [47], but our predictions are supported by over 50 years of observations. We found that the temperature increased the most from February to April. We also found strong correlations between the prevalence of Ae. albopictus and observed winter to early spring temperature, the months with the greatest temperature increase, indicating that the warming temperature may have major impact on the northward expansion of the Ae. albopictus distribution. The projected temperatures in 2050 and 2080 in this study were approximately 1–1.5 °C higher than those projected by GCMs. Our model predicted that Ae. albopictus risk will expand to nearly all populated areas in China and the risk season will expand from June–September to April–October by 2050, likely due to the substantial increase in temperature from February to April. We estimated that the current population at risk of Ae. albopictus in China is approximately 960 million, or approximately 68% of the total population, and will reach 1.2 billion or approximately85% of the current population by 2050.

Dengue outbreaks in China have been reported in Shandong, Henan, and Chongqing provinces [19,20,21, 32, 54], which are not far from the current known northern Ae. albopictus distribution boundary [33], indicating that the risk of dengue outbreaks can reasonably be predicted by the distribution of the vector mosquito Ae. albopictus. Since Ae. albopictus is nearly the sole vector for recent dengue outbreaks in China [28, 29], the observed dengue outbreaks in northern China also demonstrate the urgency for updated Ae. albopictus surveillance in northern China, which is currently not available [28, 29, 50,51,52]. The increase in temperature in northern China warrants the need to use observed climate changes to examine the impact of these changes on dengue outbreak risks, both in China and worldwide. Given the wide distribution of imported dengue cases all over China [29, 66], our study is a timely example of such an approach, and our results show the power of using observed meteorological records for predicting future dengue outbreak risks.

Incidentally, it is interesting to note that Aedes species other than Ae. albopictus have also been observed in China. The known major dengue vector Ae. aegypti has been reported in Yunnan in southwestern China bordering Myanmar [53, 67], where dengue outbreaks have been reported. Ae. albopictus has also been reported in the same area [53]. Our model predicted very high risk of dengue outbreaks in Yunnan Province nearly year-round in the China-Myanmar border area. Aedes vexans has been reported from Heilongjiang Province [56], a northeastern province bordering the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Russia and Mongolia, far north of the current Ae. albopictus northern boundary. In addition, Ae. caspius and Ae. flavidorsalis have been reported in central Qinghai Province, the core area of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau [55, 68]. Culex and Anopheles mosquitoes have also been reported in these places [68]. The vector status of these Aedes mosquitoes is unknown, as is the impact of climate change on the distribution and vector status of these Aedes mosquitoes. Furthermore, Culex pipiens pipiens, Culex pipiens pallens, Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus and its hybrids have in recent years established populations in Lhasa city, Tibet Autonomous Region, 3700 m above sea level [69]; whether they can transmit diseases is unknown. However, malaria and malaria vectors have been reported in Motuo County, Tibet [70, 71], indicating the possibility of pathogen transmission at high altitudes, and climate change may enhance or support the transmission of pathogens in the highlands.

There are several limitations to this study. Although validation analysis showed that our model had high power to predict the observed presence of Ae. albopictus, the suitability model predicted the potential distribution of Ae. albopictus in the Taklamakan Desert area of southwestern Xinjiang in northwestern China, which is likely due to the lack of Ae. albopictus surveillance data and the sparse distribution of meteorological records in the area; the predicted future climate in this area was likely biased by the use of ground observations from other stations. In this context, mosquito surveillance should be enhanced by setting up more monitoring stations in western and northeastern China (see Fig. 1), and better surveillance coverage may improve the power of model predictions and capture the potentially newly invaded areas by Ae. albopictus in China. Some dengue risk models have used human population density as an independent risk predictor [9, 72, 73], which may reduce the uncertainty of model predictions; since the desert is a no-man’s land, the dengue risk will be zero. In this study, we used only climatic and environmental data [33]; therefore, we only predicted the climate suitability for dengue transmission. On the other hand, the environmental variables already included humid, sub-humid, semiarid, and arid regions as an independent variables [33], so the predicted suitability in the desert area is likely due to the lack of Ae. albopictus surveillance data from arid areas. In addition, adding the human population as a variable may not have a major impact on the overall results, because population density is high in northeastern China but no Ae. albopictus has been detected in the area, likely due to the low temperature. Since future trends in climate change may not be the same as those in the last 50 years, we cannot necessarily assume a fixed trend, i.e., the prediction of future climate change has uncertainty. However, most if not all climate models use the fixed emission assumption over time, although they allow for different emissions scenarios [40, 41, 43]. Since we used observed climatic data, the projected distribution of Ae. albopictus can be adjusted or the model calibrated when future data are updated; this may be a viable solution to address the uncertainty of future climate change. Finally, in addition to the uncertainty in future global climate change, future population growth in China is also uncertain especially by 2050 and beyond, recent birth/death records show a substantial downward trend in population growth in China. Since it is difficult to predict both the future population trend in China and population movement (thus population distribution), therefore there is an uncertainty for the prediction of future at-risk populations.

Conclusions

Dengue outbreaks have intensified in temperate northern China, in addition to the near endemic status of dengue in southern China. Climate change has also intensified in the past 50 years [74]. Ae. albopictus is rapidly expanding its distribution [41, 75, 76]. This expanded distribution, fueled by increased temperatures, will likely enhance dengue transmission especially in high-latitude and high-altitude areas, as observed from field vector surveillance. Dengue outbreaks, an old threat, have become a new challenge for future prevention and control efforts in the era of climate change. A climate-based early warning system is urgently needed so that risks can be assessed in a timely manner to support preparedness for future outbreaks.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- GCMs:

-

General circulation models

- CART:

-

The machine learning classification and regression tree

- CHAID:

-

Chi-square automatic interaction detection

References

World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

Gubler DJ, Clark GG. Dengue/Dengue hemorrhagic fever: the emergence of a global health problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:55–7.

Wilder-Smith A, Gubler DJ. Geographic expansion of dengue: the impact of international travel. Med Clin N Am. 2008;92:1377–90.

Bonizzoni M, Gasperi G, Chen X, James AA. The invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus: current knowledge and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29:460–8.

Kamal M, Kenawy MA, Rady MH, Khaled AS, Samy AM. Mapping the global potential distributions of two arboviral vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus under changing climate. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0210122.

Vavassori L, Honnen AC, Saarman N, Caccone A, Müller P. Multiple introductions and overwintering shape the progressive invasion of Aedes albopictus beyond the Alps. Ecol Evol. 2022;12(7): e9138.

Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S, Messina JP, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, et al. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(8): e1760.

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496(7446):504–7.

Messina JP, Brady OJ, Golding N, Kraemer MUG, Wint GRW, Ray SE, et al. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1508–15.

Zhao HL. The epidemic of dengue fever at Shiwanzhen of Forshan City in 1978. National Med J China. 1981;61:466–9 (in Chinese).

Liu M, Huang S, Pan C. The clinical characteristics of 1649 dengue fever cases from epidemics in Fuzhou city in 1999. Chin J Zoonoses. 2002;18:132–3 (in Chinese).

Cui F, He F, Huang X, Tian L, Li S, Liang C, et al. Dengue and dengue virus in Guangdong, China, 1978–2017: epidemiology, seroprevalence, evolution, and policies. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9: 797674.

Lai S, Huang Z, Zhou H, Anders KL, Perkins TA, Yin W, et al. The changing epidemiology of dengue in China, 1990–2014: a descriptive analysis of 25 years of nationwide surveillance data. BMC Med. 2015;13:100.

Yue YJ, Ren DS, Liu QY. Spatial-temporal distribution of dengue fever in the mainland of China, 2005–2013. Dis Surveil. 2015;30:555–60 (in Chinese).

Xu GZ, Shi NF, Dong HJ, Zhou AM, Cheng ZH, Chen GH, et al. Studies on the prevalent features of imported dengue fever and control measure. Chine Trop Med. 2006;6:1129–31 (in Chinese).

May XH, Zhang ZX. Current situation of the dengue fever in China. J Pathog Biol. 2007;2:385–8 (in Chinese).

Xiao JP, He JF, Deng AP, Lin HL, Song T, Peng ZQ, et al. Characterizing a large outbreak of dengue fever in Guangdong Province. China Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:44.

Ma HX, Du YH, Huang XY, Li XL, Xu BL. Analysis of the genome sequence of dengue virus caused an outbreak of dengue fever in Henan province, 2013. Chin J Epidemiol. 2015;36:1185–6 (in Chinese).

Yue Y, Liu X, Ren D, Wu H, Liu Q. Spatial dynamics of dengue fever in mainland China, 2019. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):2855.

Yue Y, Liu Q, Liu X, Zhao N, Yin W. Dengue fever in mainland China, 2005–2020: a descriptive analysis of dengue cases and Aedes data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(7):3910.

Lun X, Wang Y, Zhao C, Wu H, Zhu C, Ma D, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and temporal-spatial analysis of overseas imported dengue fever cases in outbreak provinces of China, 2005–2019. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(1):12.

Luo C, Chen Q, Tan SB, Xiong XW, Cheng XT, Yan CY. Epidemic characteristics and influential factors of dengue fever in Wanzhou, Chongqing, 2019. China Trop Med. 2021;21:654–8 (in Chinese).

Huang DQ, Liu L, Chen Q, Wu Y, Liu M, Xiong JF. Analysis of dengue epidemic and Aedes vector surveillance in Hubei province, China, 2019. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2021;32:38–40 (in Chinese).

Wang CZ, Zhang BY, Chen WZ, Chen YB. Report of three outbreaks of dengue and dengue homorganic fever in Hainan Island. Dis Surveil. 1992;7:151–5 (in Chinese).

Meng FX, Wang YG, Feng L, Liu Q. Review on dengue prevention and control and integrated mosquito management in China. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2015;26(1):4–10 (in Chinese).

Wang YY, Lu BL, Wu ZQ, Gan BJ, Chen WW, Wu RX. Integrated control of Aedes aegypti in Hainan Island. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 1996;7:12–5 (in Chinese).

Wang ZG, Wang SQ, Masaji ONO, Takagi M, Yoshio T, Zeng HL, et al. Investigation on Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus in the north-western part of Hainan Province. Chine Trop Med. 2005;5(02):230–3 (in Chinese).

Liu Q. Dengue fever in China: new epidemiological trend, challenges and strategies for prevention and control. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2020;31:1–6 (in Chinese).

Liu X, Liu Q. Aedes surveillance and risk warnings for dengue—China, 2016–2019. CCDC Weekly. 2020;2:431–7.

Li Y, Zhou G, Zhong S, Wang X, Zhong D, Hemming-Schroeder E, et al. Spatial heterogeneity and temporal dynamics of mosquito population density and community structure in Hainan Island, China. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13(1):444.

Fan JH, Gao Y, Zhu J, Huang Q, Li JM, Su MH, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of dengue fever and surveillance results of Aedes mosquitoes in Xishuangbanna Prefecture, Yunnan province, China, 2006–2020. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2022;33:245–52.

Liu H, Liu L, Cheng P, Yang L, Chen J, Lu Y, et al. Bionomics and insecticide resistance of Aedes albopictus in Shandong, a high latitude and high-risk dengue transmission area in China. Parasit Vector. 2020;13:11.

Zheng X, Zhong D, He Y, Zhou G. Seasonality modeling of the distribution of Aedes albopictus in China based on climatic and environmental suitability. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8(1):98.

Xu L, Stige LC, Chan KS, Zhou J, Yang J, Sang S, et al. Climate variation drives dengue dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(1):113–8.

Zhang Q, Chen Y, Fu Y, Liu T, Zhang Q, Guo P, et al. Epidemiology of dengue and the effect of seasonal climate variation on its dynamics: a spatio-temporal descriptive analysis in the Chao-Shan area on China’s southeastern coast. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5): e024197.

Riad MH, Cohnstaedt LW, Scoglio CM. Risk Assessment of dengue transmission in Bangladesh using a spatiotemporal network model and climate data. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104(4):1444–55.

van Panhuis WG, Choisy M, Xiong X, Chok NS, Akarasewi P, Iamsirithaworn S, et al. Region-wide synchrony and traveling waves of dengue across eight countries in Southeast Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(42):13069–74.

Kakarla SG, Caminade C, Mutheneni SR, Morse AP, Upadhyayula SM, Kadiri MR, et al. Lag effect of climatic variables on dengue burden in India. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147: e170.

Cunze S, Koch LK, Kochmann J, Klimpel S. Aedes albopictus and Aedes japonicus—two invasive mosquito species with different temperature niches in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):573.

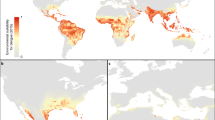

Ryan SJ, Carlson CJ, Mordecai EA, Johnson LR. Global expansion and redistribution of Aedes-borne virus transmission risk with climate change. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(3): e0007213.

Khan SU, Ogden NH, Fazil AA, Gachon PH, Dueymes GU, Greer AL, et al. Current and projected distributions of Aedes aegypti and Ae albopictus in Canada and the U.S. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128(5):57007.

Back AT, Lundkvist A. Dengue viruses—an overview. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2013;30:3.

Caminade C, Medlock JM, Ducheyne E, McIntyre KM, Leach S, Baylis M, et al. Suitability of European climate for the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus: recent trends and future scenarios. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(75):2708–17.

Fan JC, Liu QY. Potential impacts of climate change on dengue fever distribution using RCP scenarios in China. Adv Climate Change Res. 2019;10:1–8.

Xu Z, Bambrick H, Frentiu FD, Devine G, Yakob L, Williams G, et al. Projecting the future of dengue under climate change scenarios: progress, uncertainties and research needs. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(3): e0008118.

Soneja S, Tsarouchi G, Lumbroso D, Tung DK. A review of dengue’s historical and future health risk from a changing climate. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2021;8(3):245–65.

Pörtner H O, Roberts D C, Tignor MMB, Poloczanska E, Mintenbeck K, Alegria A, et al. Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, 2022. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

Rantanen M, Karpechko AY, Lipponen A, Nordling K, Hyvärinen O, Ruosteenoja K, et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun Earth Environ. 2022;3:168.

Iwamura T, Guzman-Holst A, Murray KA. Accelerating invasion potential of disease vector Aedes aegypti under climate change. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2130.

Li C-Y, Tian F-Y, Ling Y-N, Xiao C-K, Zhang F-Y. Monitoring of the density of the dengue vector Aedes albopictus and its resistance to commonly used insecticides in Zigong of Sichuan province, China. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2021;32(3):307–11 (in Chinese).

Tu T-T, Xiao H-S, Luo C, Tao X-Y, Zhang X-H, Liang W, et al. Ecological surveillance analysis of dengue vector Aedes in Chongqing, 2020. China Trop Med. 2021;21(7):667–70 (in Chinese).

Zhang J-L, Huang F-Y. Surveillance results of dengue vector Aedes in Anhui province of China, 2015–2019. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2021;32(5):582–5 (in Chinese).

Zhou K-M, Yang M-D, Lan X-M, Zheng Y-T, Tang Y-R, Wu C, et al. An investigation of the distribution of dengue vector Aedes in the main urban areas of 129 counties (cities, districts) of Yunnan province, China. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2021;32(2):150–7 (in Chinese).

Cao YO, Zhou XY, Liu XC, Liu Q. An analysis of surveillance results of dengue vector Aedes in Sichuan province, China, 2016–2018. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2020;31:185–92 (in Chinese).

Cui S-H, Fu S-H, Zhao S-C, Cao L, Fu J-N, Tang Z-J, et al. Investigation of mosquitoes and arboviruses in Delingha area in Qinghai, 2013. Dis Surveil. 2016;31(4):346–50 (in Chinese).

Yuan S, Ge T, Tang L, Yin S-H, Xing Z-F. An analysis of mosquito surveillance results from vector surveillance sites in Heilongjiang province, China, 2007–2017. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2021;32(1):52–5 (in Chinese).

Harris I, Jones PD, Osborn TJ, Lister DH. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations - the CRU TS3.10 Dataset. Int J Climatol. 2014;34:623–42.

Kass GV. An exploratory technique for investigating large quantities of categorical data. J R Stat Soc C. 1980;29(2):119–27.

Biggs D, De Ville B, Suen E. A method of choosing multiway partitions for classification and decision trees. J Appl Stat. 2006;18:49–62.

Antipov E, Pokryshevskaya E. Applying CHAID for logistic regression diagnostics and classification accuracy improvement. J Target Meas Anal Mark. 2010;18(2):109–17.

Warrens MJ. On association coefficients for 2 × 2 tables and properties that do not depend on the marginal distributions. Psychometrika. 2008;73(4):777.

Zhou G, Lee M-C, Wang X, Zhong D, Yan G. Mapping potential malaria vector larval habitats for larval source management: Introduction to multi-model ensembling approaches. bioRxiv. 2022:2022.10.06.511086.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med. 2012;22(3):276–82.

Isaaks EH, Srivastava RM. An introduction to applied geostatistics. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 1989.

China Data Center. University of Michigan. China County Map with 2010 Population Census Comparation Data from Long Form Data. Copyright by All China Marketing Research Co., Ltd; Beijing 2010. http://purl.stanford.edu/zb352pb5096.

Lin H, Wang X, Li Z, Li K, Lin C, Yang H, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of dengue in mainland China from 1990 to 2019: a descriptive analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(36): e21982.

Liu P, Lu L, Jiang J, Guo Y, Yang M, Liu Q. The expanding pattern of Aedes aegypti in southern Yunnan, China: insights from microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA markers. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:561.

Li WJ, Wang JL, Li MH, Fu SH, Wang HY, Wang ZY, et al. Mosquitoes and mosquito–borne arboviruses in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau–focused on the Qinghai area, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(4):705–11.

Liu Q, Liu X, Cirendunzhu, Woodward A, Pengcuociren, Bai L, et al. Mosquitoes established in Lhasa city, Tibet, China. Parasit Vector. 2013;6:224.

Wu S, Huang F, Zhou SS, Tang LH. Study on malaria vectors in malaria endemic areas of Tibet autonomous region. Chin J Schisto Control. 2012;24(6):711–3 (in Chinese).

Wu S, Huang F, Wang D-Q, Xu G-J, Jiang W-K, Zhou S-S, et al. Ecological behavior comparison between Anopheles pseudowillmori and A. willmori in villages with malaria outbreaks in Motuo County, Tibet Autonomous Region. Chin J Schisto Control. 2013;25(4):362–6 (in Chinese).

Schmidt WP, Suzuki M, Thiem VD, White RG, Tsuzuki A, Yoshida LM, et al. Population density, water supply, and the risk of dengue fever in Vietnam: cohort study and spatial analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8(8): e1001082.

Akter R, Hu W, Naish S, Banu S, Tong S. Joint effects of climate variability and socioecological factors on dengue transmission: epidemiological evidence. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(6):656–69.

Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Péan C, Berger S, et al. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. IPCC. 2022.

Kraemer MUG, Reiner RC Jr, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Gilbert M, Pigott DM, et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4(5):854–63.

Oliveira S, Rocha J, Sousa CA, Capinha C. Wide and increasing suitability for Aedes albopictus in Europe is congruent across distribution models. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9916.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their constructive comments and suggestions to improve our manuscript. We also wish to thank Ms. Brook Jeang for final language proofreading.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81702034 to HML, and 81871685 to MQG), Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2020KH001 to HML), NHC Key Laboratory of Parasite and Vector Biology (National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Center for Diseases Prevention and Control, NHCKFKT2021-02 to HML), Academic Promotion Programme of the Shandong First Medical University (2019QL005) and The Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data acquisition, HML, XXG, PC, XDH, HFW, LJL, CHZ, CXZ and XJW. Data sorting and analysis, HML and GZ. Funding acquisition, HML, PC and MQG. Methodology and software, HML and GZ. Supervision, XJW, GZ and MQG. Draft writing, HML. Writing, review and editing, HML, XDH, GZ and MQG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1

. Distribution of meteorological stations in China where 1970–2021 climatic records were obtained.

Additional file 2: Figure S2

. Univariate analyses of relationship between Ae. albopictus presence and climatic variables. a) Monthly mean temperature (°C); b) Monthly maximum temperature (°C); and c) Monthly minimum temperature (°C). Acc stands for accuracy. Yale represents Yale’s association. Dash line represents the optimal cutoff of temperature.

Additional file 3: Figure S3

. a) Examples of changes in monthly minimum temperature in different places; b) Examples of changes in annual precipitation in different places.

Additional file 4: Figure S4

. Distribution of annual changes in mean (a), maximum (b), and minimum (c) temperature from January to December for the period 1970–2021.

Additional file 5: Figure S5

. Universal Kriging estimated annual changes in precipitation (mm) in China.

Additional file 6

: A Machine Learning Classification and Regression Trees (CART) for Aedes albopictus distribution modeling. B. Universal Kriging for spatial interpolation of annual climate changes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Huang, X., Guo, X. et al. Climate change and Aedes albopictus risks in China: current impact and future projection. Infect Dis Poverty 12, 26 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-023-01083-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-023-01083-2