Abstract

Background

Prevention of tuberculosis (TB)-related stigma is vital to achieving the World Health Organisation’s End TB Strategy target of eliminating TB. However, the process and impact evaluation of interventions to reduce TB-stigma are limited. This literature review aimed to examine the quality, design, implementation challenges, and successes of TB-stigma intervention studies and create a novel conceptual framework of pathways to TB-stigma reduction.

Method

We searched relevant articles recorded in four scientific databases from 1999 to 2022, using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, supplemented by the snowball method and complementary grey literature searches. We assessed the quality of studies using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool, then reviewed study characteristics, data on stigma measurement tools used, and interventions implemented, and designed a conceptual framework to illustrate the pathways to TB-stigma reduction in the interventions identified.

Results

Of 14,259 articles identified, eleven met inclusion criteria, of which three were high quality. TB-stigma reduction interventions consisted mainly of education and psychosocial support targeted predominantly toward three key populations: people with TB, healthcare workers, and the public. No psychosocial interventions for people with TB set TB-stigma reduction as their primary or co-primary aim. Eight studies on healthcare workers and the public reported a decrease in TB-stigma attributed to the interventions. Despite the benefits, the interventions were limited by a dearth of validated stigma measurement tools. Three of eight studies with quantitative stigma measurement questionnaires had not been previously validated among people with TB. No qualitative studies used previously validated methods or tools to qualitatively evaluate stigma. On the basis of these findings, we generated a conceptual framework that mapped the population targeted, interventions delivered, and their potential effects on reducing TB-stigma towards and experienced by people with TB and healthcare workers involved in TB care.

Conclusions

Interpretation of the limited evidence on interventions to reduce TB-stigma is hampered by the heterogeneity of stigma measurement tools, intervention design, and outcome measures. Our novel conceptual framework will support mapping of the pathways to impacts of TB-stigma reduction interventions.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stigma experienced by people with or affected by tuberculosis (TB)—henceforth termed TB-stigma—remains one of the major challenges in TB control [1, 2]. TB-stigma has been shown to delay health-seeking behaviour [3]. This challenge has been aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic which has restricted access to healthcare, reduced the number of people notified with TB, and been associated with an increase in TB mortality [1, 4, 5]. TB-stigma has also been shown to reduce treatment compliance, and negatively impact on TB treatment outcomes [6, 7]. The prevalence of TB-stigma varies geographically and, in specific subpopulations, has been estimated to affect up to 80% of people with TB [8, 9]. Therefore, in the context of TB control, TB-stigma is one of the major social determinants of health and contributes to compounding health inequalities [1, 10, 11].

For these reasons, the Global Fund and UN high-level meeting highlighted TB-Stigma as one of the most significant barriers to reaching the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB goal of eliminating TB by 2050 and called on the international community to “promote and support an end to stigma and all forms of discrimination” [12,13,14]. Despite this, few resources have been mobilised to address this issue [15]. In part, this is due to inherent difficulties in the identification and measurement of TB-Stigma and the complexity and limited evidence base relating to stigma-reduction interventions [16].

Measuring stigma is vital to understand its determinants, prevalence and assess the effectiveness of stigma-reduction interventions [17]. Multiple scales and tools exist that assess health-related stigma [18]. To be robust and reliable, these tools should have been validated in the community or population in which they are to be used and then refined to ensure they are accurate, specific, and reliable. In 2018, the KNCV Tuberculosis Foundation created a TB-Stigma Handbook, which provides examples of how the limited available set of existing tools can best be applied to measure and evaluate stigma [19]. However, most studies to date have used either disparate, invalidated tools or solely qualitative measures of stigma. This has made it difficult to broaden our understanding of the determinants and consequences of TB-Stigma [15, 20] (Box 1).

In addition, despite recognition of the global importance of TB-stigma, there has been limited critical appraisal in the literature of the few existing interventions aimed at reducing TB-stigma. The single related systematic review on TB-Stigma by Sommerland et al. focused on the effectiveness of stigma-reduction interventions [17]. Measuring and reducing TB-Stigma is complex. It involves interrelated, heterogeneous system structures, and multiple approaches from the individual to societal level [16]. Therefore, it is critical to evaluate not only the scale but also the challenges and successes in the design and implementation processes of interventions to reduce TB-stigma. These evaluations will help identify the weaknesses in current TB-stigma intervention design and delivery in order to refine these interventions for future implementation and scale-up.

We reviewed studies reporting interventions to reduce TB-Stigma. The review appraised the study design and stigma measurement tools, identified their challenges and successes, and evaluated their pathways to impact on TB-Stigma. We then developed a conceptual framework for the TB-Stigma reduction pathway to support researchers to successfully design and deliver impactful TB-stigma reduction interventions.

Methods

This study was a systematic literature review. A preliminary scoping search was conducted to ensure that all relevant key terms were identified, and the final search strategy refined.

Search terms and management of search results

The following search terms were used within four databases (CINAHL Complete, Medline Complete, Global Health and PubMed): (TB OR Tubercul* OR “Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections”) AND (stigma* OR discrimin* OR “social stigma” OR barrier* OR attitude* OR “social discrimination” OR marginalisation OR “psychosocial impact” OR “socioeconomic impact” OR shame OR “social isolation” OR “social inclusion” OR prejudice OR perception OR “self-esteem”) AND (interven* OR strateg* OR pathway* OR education OR “psychosocial intervention*” OR “psychoemotional intervention*” OR “socioeconomic intervention*” OR “social support” OR “patient support” OR “training workshop*” OR “counselling”) were searched. In addition, the “snowballing” method of reference tracking and searches of Google Scholar and the WHO database for grey literature were used to identify additional articles that may have been overlooked by the initial search strategy. Searches were limited to December 31, 2021. Citations of the articles identified from the searches were exported into Endnote X9 (Camelot UK Bidco Limited/Clarivate, UK). Duplicates were then identified and removed using the duplicates tool in Endnote X9. The titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were read through and screened for relevance independently by three reviewers (CN, HN, AF). Where there were unresolved disagreements, a fourth senior reviewer finalized screening for inclusion or exclusion (TW). We applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, documented the reasons for article exclusion, and identified the relevant articles for full-text review. Finally, supplemental manual review of the reference lists of the selected full-text articles was performed to identify any further articles for inclusion.

Selection criteria

Eligible studies included those that reported the implementation and evaluation of TB-stigma reduction interventions amongst people with TB and their households, healthcare workers, and the general public. Included study designs were intervention studies with randomised controlled trials, non-randomised controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, mixed-methods studies, qualitative studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. The review was restricted to articles that were written in English. Articles were excluded if they did not report measurement of stigma.

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal was undertaken by three reviewers (CN, HN, AF) using the “Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool” (CCAT), Version 1.4, to determine the quality of each study [21]. The CCAT was selected as it has been proven to be reliable and valid for the analysis of multiple studies of heterogenous design and implementation approaches, and can reduce rater bias [22]. To further reduce researcher bias, each individual assessment was cross-checked. A fourth reviewer (TW) resolved any discrepancies. A priori, and in line with published guidance [21], a pragmatic decision was taken by the study team that articles with a CCAT score between 75% and 100% would be deemed high quality, 50% and 74% moderate, and below 50% to be low quality.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data on country and region of intervention, target population, type of stigma studied, the scale or tool used to assess stigma, intervention activities, challenges and successes of intervention, the impact of intervention, and reported changes to TB practice and policy were collated and tabulated. Further information on the intervention including format, content, outcomes (both reported and intended if different) and detail on how the intervention reduced TB-stigma (theory explicitly stated in the main text or implied in objectives or methods) were also tabulated. Qualitative details were lifted directly from the text and copied into the data-extraction table. The articles were read carefully for similar and recurring themes and concepts. The concepts were then organised to determine any contradictory concepts, which were then removed. A conceptual framework was then created to organise the variables and concepts perceived by the research team to contribute to the pathways by which an intervention successfully reduced TB-stigma. The intention of the novel conceptual framework was to support researchers to design, develop, and implement a successful and sustainable stigma-reduction intervention in current and future studies [23]. With respect to stigma measurement tools and scales, these were evaluated through collection of data including: the tool or scale used; implementation methods; methods to reduce bias and ensure validity; internal and external validation and piloting prior to use; comparison of stigma scores before and after the intervention or between study groups; types of stigma assessed; whether the tool was adapted from a previously validated tool; and the described limitations of the tool. Any required data that was missing from the published papers was collected by directly contacting the corresponding author of the paper.

Results

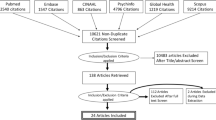

The search yielded 14,244 articles with 15 further articles identified from other sources including grey literature. After removal of duplicate articles, 10,954 were screened, 54 of which met the study inclusion criteria. Following the full-text eligibility assessment, 43 further articles were excluded (Additional file 1). The remaining 11 articles were included for critical appraisal in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

The median CCAT score for quality of studies was 24/40 (range 15–38) (Additional file 1). Three studies were classified as high quality [24,25,26]. The predominant reasons for lower quality scoring were lack of details relating to methods and study protocols including sampling frames and ethical approval.

Study characteristics

There was marked heterogeneity in the study characteristics in terms of study aims, designs, population and region/sites, and type of stigma measured (Table 1). The studies were conducted in low- (n = 1) [27], middle- (n = 9) [24,25,26, 28,29,30,31,32,33], and high-income (n = 1) countries [34]. Two studies were conducted in the same country (Peru) [30, 31], and these studies were linked with some overlap of study team members and co-authors. The studies were targeted at a variety of different populations including people with TB and MDR-TB and their households (n = 5), HCWs (n = 3), and the public (n = 3).

Study population, aims and intervention

Six studies applied interventions targeted towards people with TB. Five of the studies aimed to improve TB treatment compliance and completion through psychosocial support interventions, which were TB clubs or support groups (n = 3) [28,29,30], nurse support (n = 1) [31], and household counselling (n = 1) [26], while one study focused on improving TB knowledge [33].

TB clubs involved group meetings of people diagnosed with TB to discuss their experiences and provide mutual support to encourage each other through their illness and treatment. Other studies initiated patient-centred home visits by HCWs to complement the TB clubs [30], provided individualised emotional support from community nurses who informed and educated people with TB and their households about TB [31], and implemented a household counselling intervention delivered by nurses and trained counsellors [26]. All of the studies tailored towards people with TB captured stigma related to being diagnosed with TB. The assessment focused on measuring enacted and internalised stigma and, where possible, the influence of such stigma on TB treatment success rates. Two of the studies also involved family members of people with TB: one to evaluate stigma [26] and another to evaluate people with TB and their family members’ TB knowledge following delivery of educational videos while waiting at TB outpatient clinic appointments [33].

Two studies evaluated stigma among HCWs using workshops focused on distinct aspects of stigma [24, 34]. One delivered nationwide TB training workshops to educate HCWs on TB, stigma and human rights to improve knowledge on TB and reduce TB-stigma towards people with TB [34]. In another, there was a focus on healthcare workers who were themselves stigmatised by other HCWs [24]. This study measured external or secondary stigma, in which HCWs experience negative attitudes or rejection because of the care they have given to people with TB.

Three studies assessed anticipated TB-Stigma among the public: two in an adult population and one in an adolescent population. All the studies measured anticipated TB-stigma using before-after intervention designs. Two studies applied health education programs in the community (mass information programs and health promotion at mass gatherings) [27, 32]. Another study delivered training to students and evaluated whether the training reduced their levels of anticipated TB-stigma [25].

Stigma measurement tools

Eight studies used quantitative questionnaires to measure stigma (Table 2) [24,25,26,27,28, 32,33,34]. The format of the questionnaires to measure stigma varied widely including the number of questions asked (range 3–14 questions). Three of the questionnaires were adapted from tools that were not specific to any particular disease and had been previously validated but not among people with TB [28, 29, 34]. For example, Macq et al. adapted their questionnaire from the Boyd Ritsher Mental Illness stigma scale and pre-tested it 2 years before the intervention study to improve its internal validity [28]. One study piloted the tools in six different communities (four Zambian and two South African) with six different languages (Nyanja, Bemba, Tonga, isiXhosa, Afrikaans and English) [26]. Four other studies piloted their questionnaires in a single population each [24, 25, 27, 28, 35].

Most studies (n = 7) applied the tool before and after a stigma-reduction or related intervention with the time period between the first and second application varying from 4 weeks to 18 months [24,25,26, 28, 32,33,34]. One quantitative study did not evaluate stigma before the intervention [27]. The study was an evaluation of an extensive mass health education programme that was implemented for 2–3 years in one case study area and compared to another control study area with a limited health education programme.

Four studies used qualitative methods, such as focus group discussions, interviews and observation, to evaluate stigma [24, 29,30,31]. No studies used previously validated methods or tools to qualitatively evaluate stigma. However, the qualitative approaches focused less on measurement of stigma and more on exploring how people with TB attempted to combat the stigma perceived by themselves [29] or by other people [30], and how HCWs who work with people with TB struggled to deal with stigmatisation from other HCWs [24].

Challenges, successes, and outcomes

Implementation and delivery challenges and process indicators such as fidelity, acceptability, and feasibility were infrequently measured or reported in the studies. One study caused a positive change to national practice with the production of a manual to expand the intervention to a wider population [28]. Three studies reported that a success of the intervention was that sustainable changes had been made within the study site communities [26, 29, 33]. However, there was no objective way to measure or verify these changes from the data presented within the study articles.

Four of the studies explicitly stated that their intervention was limited by geographical challenges including some populations not being reached by the intervention [25, 27, 28, 32]. This limited the external validity of the data. Three studies mentioned challenges concerning maintenance and sustainability of the programmes, including identifying participants to take part in the intervention and motivating people to continue engaging with the intervention [30, 31, 34]. Another study mentioned that inviting all HCWs to participate in a workshop about TB was problematic because hospitals were busy and understaffed [24]. The intervention itself was also challenged by issues relating to professional rank, position, and social status of different HCWs, which was perceived as limiting open discussion about the optimal ways to address stigma between HCWs (Table 3).

Pathways to impact of TB-stigma interventions

Synthesising learning from the interventions and outcomes, we found distinct pathways to reduce stigma depending on the population targeted by the intervention. We created a novel conceptual framework to illustrate these pathways (Fig. 2).

Among people with TB, stigma is a negative effect of being ill with TB, diagnosed with TB, and being on TB treatment. Stigma towards people with TB can develop in three other populations: the public, TB-related HCWs, and other HCWs. The interventions for people with TB improved TB knowledge, reduced myth and misconception related to TB, increased confidence of people with TB, and thereby reduced internalised stigma experienced by people with TB [28,29,30,31, 33]. These effects directly supported people with TB to comply with and complete TB treatment. Another study showed that, although household counselling was not specifically designed to, or found to, reduce TB-Stigma [26], health counsellors can help households manage the consequence of TB-Stigma. The main challenge in providing household counselling, particularly in communities with high levels of TB-stigma, is that the visits themselves may trigger anticipated, internalised, or enacted stigma.

Training to TB HCWs improved the HCWs’ knowledge, attitude, and practice towards people with TB [34], which may contribute to improved TB care. Conversely, our review found that TB-related HCWs were often stigmatised by other HCWs [24]. Training HCWs who care for people with TB to educate other HCWs is likely to support dissemination of knowledge and accurate information about TB-Stigma in their workplace. Although the training failed to reduce external or secondary stigma, there was a potential spill over effect that TB-related HCWs could have used the campaign materials to educate people living in their neighbourhood.

Interventions targeted towards the general public had positive impacts on knowledge, attitudes and practice related to TB as measured by knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) and stigma scores [25, 27, 32]. Mass TB education to the public was expected to increase TB knowledge and remove TB misconceptions which could result in improved community attitudes and reduced stigma towards people with TB. However, the evidence found in this review suggested that misconceptions about TB persisted, even worsened, if health education through pamphlets or posters were too short and failed to convey accurate public health messages [32].

Discussion

This literature review found that, despite the global importance of addressing TB-Stigma, there is a paucity of high-quality studies evaluating interventions to reduce TB-stigma. Intervention design across studies was heterogeneous, but education about TB frequently featured as a core intervention activity. Assessment of the impact of interventions on TB-stigma reduction was limited by a lack of well-validated tools to measure stigma. The novel conceptual framework highlighted that people with TB may experience stigma from three different populations around them: the public, TB HCWs, and other HCWs. The ideal and possibly most synergistic interventions to reduce TB-Stigma would be optimized by delivering interventions targeted towards more than one key populations at the same time.

There has been an increasing awareness of the importance of combatting TB-Stigma in recent years. This study may not have captured stigma-reduction interventions or programs at local, sub-national, or national levels due to such programs not being executed, evaluated, or reported systematically, which makes them difficult to review and compare. Among the limited studies identified, this review found that research on TB-stigma was often hampered by suboptimal design and methods for implementation and evaluation.

This review complements the Sommerland et al. paper[17] and extends its findings through a specific focus on the tools used to measure stigma reduction, a qualitative evaluation of the potential reasons underlying the success or failure of the interventions, and the creation of a novel conceptual framework of the pathways to intervention impact. By this approach, this review highlights that most TB-stigma intervention studies used tools that lacked appropriate validation. This finding is consistent with other published studies [36,37,38,39]. Using reliable, validated stigma measurement tools and methods is important and helps measure stigma accurately and consistently. It also enables the comparison of impact evaluation of stigma reduction interventions across studies and contexts. There is a list of available tools that can be used and validated [19], including Van Rie’s TB-Stigma Scale [40], one of the most adapted questionnaires to assess stigma [38], which may support researchers and implementers designing TB-stigma reduction programmes in the future.

Using qualitative approaches to measure TB-stigma has both strengths and limitations. This approach cannot precisely assess the reduction of stigma after the intervention. However, it can help explore more profound dimensions of stigma and its impact on people with TB and their households. For example, qualitative studies have been able to elicit key emotional responses to TB-Stigma, including shock, fear of being isolated or abandoned by a spouse, shame related to becoming weak and incapable of working, worry relating to loneliness, and desperation related to thoughts about TB-related death [29, 30]. Therefore, interventions incorporating mixed methods process evaluations would be both prudent and beneficial.

The conceptual framework we have generated can support understanding of the pathways through which interventions successfully reduce stigma and the parties affected. It is notable that interventions rarely have stigma-reduction as a primary aim or objective. Rather, programs often cite stigma reduction as a bridge towards TB treatment compliance, completion, and success. This may be short-sighted: besides improving treatment completion, psychosocial support is also important to prevent or alleviate anxiety, depression, and mental illness, which are well established correlates of being affected by TB [41, 42]. Not having stigma reduction as a primary or even co-primary outcome may have contributed to a lack of focus on using validated instruments to measure stigma. Given that global TB policy strongly recommends interventions to reduce TB-stigma [43, 44], it is vital that appropriately validated tools be used to measure stigma and that reduction of stigma be considered as a key individual-level outcome for people affected by TB.

The framework shows that the interventions on TB HCWs are also critical and may have potential spill over effects to other healthcare workers and the general public. TB HCWs often face secondary stigma and may be at risk of a psychosocial impact of TB themselves, particularly in areas with high co-prevalence of HIV/AIDS and TB [45, 46]. TB-stigma interventions for HCWs can be challenging to implement because they may encounter power structure problems against colleagues with higher professional rank, position, and status [24]. However, HCWs are well placed to convey anti-stigma messages to their surrounding communities and should be empowered to do so.

The framework also emphasises the potential role for synergy across different pathways of TB-stigma reduction to enhance the effectiveness of interventions. For example, improvements in community and HCWs’ KAP are likely to reduce enacted stigma. Concurrently improving people with TB’s KAP is also expected to mitigate internalised and anticipated stigma. This implies that the ideal and possibly most synergistic intervention would be optimized by delivering interventions to more than one key population. TB clubs, for example, often only benefit people with TB. Stigma-reduction activities and interventions should aim to be more inclusive where possible with HCWS and/or community members being encouraged to attend and participate in TB club meetings, helping to act on all three forms of stigma.

Given that social and economic determinants and consequences of TB are now recognised as significant limiting factors for ending TB, it is notable that there is no recognised national or global indicator for TB-stigma [47]. Currently, there is a global indicator of TB-related catastrophic costs. This indicator has already proven highly useful within research and National TB Programme activities [48] and has led to the creation of a WHO database of the financial burden of TB for more than twenty countries [1]. The same approach should be taken to document the psychosocial burden of TB-stigma across countries. We would strongly advocate for a unified, adaptable global TB-stigma indicator. It could support research and activities to gather data on the prevalence of stigma in different countries or regions. It would also eventually garner further resource investment and scientific interest and heighten much-needed advocacy in this field.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the heterogeneity of study designs, quality, interventions, and tools used, it was not possible to quantitatively determine the effectiveness of interventions. While this was a weakness, the focus was on qualitative assessment of the studies. Second, only articles written in English were included, therefore, some relevant literature may have been missed, particularly of research performed in high TB burden countries in which English is not the first language. Third, paper quality was moderate, and some papers had missing data, which—despite contacting corresponding authors—was not made available for analysis. As our analysis suggested that most papers included were of only low or moderate quality, the power of this review to make conclusions about study impacts is limited [49]. Fourth, we were not able to include studies of complex interventions that aimed to minimise both the psychosocial (e.g. stigma) and economic (e.g. catastrophic costs) of TB, such as the randomised-controlled HRESIPT and CRESIPT studies in Peru [50,51,52]. While TB treatment, prevention, and economic outcomes from these studies are available, the impact of these interventions on stigma is not yet known. While publication bias is a limitation of any review of the published literature, we attempted to mitigate this bias through a comprehensive grey literature review. Despite the comprehensive evaluation of stigma reduction interventions, this review and framework could not capture the complexity of stigma, which—from a social perspective—involves a set of interrelated, heterogeneous system structures [16].

Conclusions

Despite the global importance of addressing TB-Stigma, there is a paucity of high-quality studies evaluating interventions to reduce TB-stigma. The novel conceptual framework highlighted that people with TB may experience internalized stigma and anticipated or enacted stigma from three different populations around them: the public, TB HCWs, and other HCWs. Interventions for people with TB can effectively provide psychosocial support for treatment completion. Interventions on HCWs can enhance the support provided for people with TB, and interventions for the public have the potential to reduce community-level stigma toward people with TB. The ideal and possibly most synergistic intervention would be optimized by delivering interventions to more than one key population. Finally, our findings reinforce that it is vital to promote stigma as an indicator in national and international TB strategies to strengthen the development and evaluation of stigma-reducing interventions.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional information files.

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Datiko DG, Jerene D, Suarez P. Stigma matters in ending tuberculosis: nationwide survey of stigma in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):190.

Teo AKJ, Singh SR, Prem K, Hsu LY, Yi S. Duration and determinants of delayed tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment in high-burden countries: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):251.

Pai M, Kasaeva T, Swaminathan S. COVID-19’s devastating effect on tuberculosis care—a path to recovery. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1490–3.

Chapman HJ, Veras-Estévez BA. Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic to strengthen TB Infection control: a rapid review. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;9(4):964–77.

Chang SH, Cataldo JK. A systematic review of global cultural variations in knowledge, attitudes and health responses to tuberculosis stigma. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(2):168–73.

Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2007;4(7): e238.

Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(4_suppl):34–42.

Chowdhury MRK, Rahman MS, Mondal MNI, Sayem A, Billah B. Social impact of stigma regarding tuberculosis hindering adherence to treatment: a cross sectional study involving tuberculosis patients in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2015;68(6):461–6.

Bonadonna LV, Saunders MJ, Zegarra R, Evans C, Alegria-Flores K, Guio H. Why wait? The social determinants underlying tuberculosis diagnostic delay. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185018.

Craig GM, Daftary A, Engel N, O’Driscoll S, Ioannaki A. Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:90–100.

World Health Organization. The end TB strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

The Global Fund. Tuberculosis and human right. In: The UN General Assembly high-level meeting on ending TB. The Global Fund; 2018.

United Nations. United Nations high-level meeting on the fight against tuberculosis. New York: United Nations; 2018.

Macintyre K, Bakker MI, Bergson S, Bhavaraju R, Bond V, Chikovore J, et al. Defining the research agenda to measure and reduce tuberculosis stigmas. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(11):S87–96.

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK. The stigma complex. Ann Rev Sociol. 2015;41(1):87–116.

Sommerland N, Wouters E, Mitchell EMH, Ngicho M, Redwood L, Masquillier C, et al. Evidence-based interventions to reduce tuberculosis stigma: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(11):S81–6.

Partnership STB. TB stigma assessment: implementation handbook. Geneva: Stop TB Partnership; 2019.

Challenge TB. TB stigma measurement guidance. Den Haag: KNCV; 2018.

Hartog K, Hubbard CD, Krouwer AF, Thornicroft G, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD. Stigma reduction interventions for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review of intervention strategies. Soc Sci Med. 2020;246: 112749.

Crowe M. Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) v 1.4. Queensland; 2013.

Crowe M, Sheppard L. A general critical appraisal tool: an evaluation of construct validity. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(12):1505–16.

Thapa S, Hannes K, Cargo M, Buve A, Aro AR, Mathei C. Building a conceptual framework to study the effect of hiv stigma-reduction intervention strategies on HIV test uptake: a scoping review. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2017;28(4):545–60.

Sommerland N, Masquillier C, Rau A, Engelbrecht M, Kigozi G, Pliakas T, et al. Reducing HIV- and TB-stigma among healthcare co-workers in South Africa: results of a cluster randomised trial. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266: 113450.

Idris NA, Zakaria R, Muhamad R, Nik Husain NR, Ishak A, Wan Mohammad WMZ. The effectiveness of tuberculosis education programme in Kelantan, Malaysia on knowledge, attitude, practice and stigma towards tuberculosis among adolescents. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27(6):102–14.

Bond V, Floyd S, Fenty J, Schaap A, Godfrey-Faussett P, Claassens M, et al. Secondary analysis of tuberculosis stigma data from a cluster randomised trial in Zambia and South Africa (ZAMSTAR). Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(11):49–59.

Croft RP, Croft RA. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding leprosy and tuberculosis in Bangladesh. Lepr Rev. 1999;70(1):34–42.

Macq J, Solis A, Martinez G, Martiny P. Tackling tuberculosis patients’ internalized social stigma through patient centred care: an intervention study in rural Nicaragua. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:154–154.

Demissie M, Getahun H, Lindtjørn B. Community tuberculosis care through “TB clubs” in rural North Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(10):2009–18.

Acha J, Sweetland A, Guerra D, Chalco K, Castillo H, Palacios E. Psychosocial support groups for patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: five years of experience. Glob Public Health. 2007;2(4):404–17.

Chalco K, Wu DY, Mestanza L, Muñoz M, Llaro K, Guerra D, et al. Nurses as providers of emotional support to patients with MDR-TB. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(4):253–60.

Balogun M, Sekoni A, Meloni ST, Odukoya O, Onajole A, Longe-Peters O, et al. Trained community volunteers improve tuberculosis knowledge and attitudes among adults in a periurban community in southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(3):625–32.

Wilson JW, Ramos JG, Castillo F, Castellanos EF, Escalante P. Tuberculosis patient and family education through videography in El Salvador. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2016;4:14–20.

Wu PS, Chou P, Chang NT, Sun WJ, Kuo HS. Assessment of changes in knowledge and stigmatization following tuberculosis training workshops in taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(5):377–85.

Wouters E, Rau A, Engelbrecht M, Uebel K, Siegel J, Masquillier C, et al. The development and piloting of parallel scales measuring external and internal HIV and tuberculosis stigma among healthcare workers in the Free State Province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(suppl_3):S244–54.

Sommerland N, Wouters E, Mitchell EMH, Ngicho M, Redwood L, Masquillier C, et al. Evidence-based interventions to reduce tuberculosis stigma: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(11):81–6.

Sengupta S, Banks B, Jonas D, Miles MS, Smith GC. HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1075–87.

Bergman A, McNabb K, Farley JE. A systematic review and psychometric appraisal of instruments measuring tuberculosis stigma in Sub-Saharan Africa. Stigma Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000328.

MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP. Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Q. 2011;35(2):293–334.

Van Rie A, Sengupta S, Pungrassami P, Balthip Q, Choonuan S, Kasetjaroen Y, et al. Measuring stigma associated with tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in southern Thailand: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of two new scales. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(1):21–30.

Koyanagi A, Vancampfort D, Carvalho AF, DeVylder JE, Haro JM, Pizzol D, et al. Depression comorbid with tuberculosis and its impact on health status: cross-sectional analysis of community-based data from 48 low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):209–209.

Naidu T, Pillay SR, Ramlall S, Mthembu SS, Padayatchi N, Burns JK, et al. Major depression and stigma among individuals with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1067–71.

Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):34–42.

Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN. Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):211.

Wouters E, Sommerland N, Masquillier C, Rau A, Engelbrecht M, van Rensburg AJ, et al. Unpacking the dynamics of double stigma: how the HIV-TB co-epidemic alters TB stigma and its management among healthcare workers. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):106.

Rau A, Wouters E, Engelbrecht M, Masquillier C, Uebel K, Kigozi G, et al. Towards a health-enabling working environment—developing and testing interventions to decrease HIV and TB stigma among healthcare workers in the Free State, South Africa: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):351.

Lönnroth K, Glaziou P, Weil D, Floyd K, Uplekar M, Raviglione M. Beyond UHC: monitoring health and social protection coverage in the context of tuberculosis care and prevention. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9): e1001693.

Viney K, Islam T, Hoa NB, Morishita F, Lönnroth K. The financial burden of tuberculosis for patients in the Western-Pacific region. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4(2):94.

Peters SE, Johnston V, Coppieters MW. Interpreting systematic reviews: looking beyond the all too familiar conclusion. J Hand Ther. 2014;27(1):1–3.

Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Huff D, Boccia D, Montoya R, Ramos E, et al. Socioeconomic support to improve initiation of tuberculosis preventive therapy and increase tuberculosis treatment success in Peru: a household-randomised, controlled evaluation. Lancet. 2017;389:S16.

Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Huff D, Boccia D, Montoya R, Ramos E, et al. A randomized controlled study of socioeconomic support to enhance tuberculosis prevention and treatment, Peru. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(4):270.

Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Huff D, Boccia D, Montoya R, Ramos E, et al. The economic effects of supporting tuberculosis-affected households in Peru. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(5):1396–410.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

TW is supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust, UK (209075/Z/17/Z), the Medical Research Council, Department for International Development, and Wellcome Trust (Joint Global Health Trials, MR/V004832/1), and a Dorothy Temple Cross Tuberculosis International Collaboration Grant from the Medical Research Foundation, UK. AF and TW are recipients of a Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene early career research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CN and AF led the construction and write-up of the manuscript. TW advised throughout the process of constructing the study and was the lead editor of the manuscript. HN was the second reviewer of papers. KD and MM reviewed the manuscript and provided substantial comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This review was conducted without patient or public involvement and did not need ethical approval.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed on the final version of the manuscript and gave consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Excluded studies reasoning and Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) Score.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nuttall, C., Fuady, A., Nuttall, H. et al. Interventions pathways to reduce tuberculosis-related stigma: a literature review and conceptual framework. Infect Dis Poverty 11, 101 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-01021-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-01021-8