Abstract

We study urban, private sector Chinese employers’ preferences between workers with and without a local permanent residence permit (hukou) using callback information from an Internet job board. We find that these employers prefer migrant workers to locals who are identically matched to the job’s requirements; these preferences are strongest in jobs requiring lower levels of education and offering low pay. While migrant-native payroll tax differentials might account for some of this gap, we argue that the patterns are hard to explain without some role for a migrant productivity advantage in less skilled jobs. Possible sources of this advantage include positive selection of nonlocals into migration, negative selection of local workers into formal search for unskilled private sector jobs, efficiency wage effects related to unskilled migrants’ limited access to the urban social safety net, and intertemporal labor and effort substitution by temporary migrants that makes them more desirable workers.

Jel codes: O15, R23

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A common claim in popular discussions of migration is that employers prefer to hire workers with limited residency rights—such as temporary or undocumented migrants—over equally qualified natives, because these migrant workers are willing to work harder, for longer hours, or for less pay. Such claims coexist with others arguing that employers discriminate against migrants, either for taste-based reasons or out of a desire to protect native workers.Footnote 1 Yet despite substantial literatures on the labor market outcomes of temporary and undocumented migrants (e.g., Dustmann 2000, Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark 2002, Kahanec and Shields 2013), it appears that no study has examined employers’ hiring choices between workers with different residency rights in any jurisdiction.Footnote 2

This paper studies employers’ choices between workers with and without permanent residency rights in a context that has been called the largest migration in human history (Chan, 2013). In 2010, the internal rural migrant population in China’s cities was estimated at 206 million persons, or about two thirds of the entire U.S. population (Chan 2012, Table 1). A noteworthy feature of this migration is that unlike the U.S., and unlike many other developing nations, Chinese people do not have the right to permanently reside in any part of the country. Instead, each person is born with a city or province of permanent registration (hukou). While this does not prevent people from migrating to other jurisdictions for temporary work, it places severe limits on their ability to settle permanently in any location other than the one corresponding to their birth hukou. Since a worker’s hukou status is relatively public information, China’s internal migration system provides a unique laboratory in which to study employers’ preferences between workers with different residency rights.

To that end, this paper uses internal data from XMRC, an Internet job board in Xiamen, a medium-sized, prosperous Chinese city, to pose the following question: among equally qualified local hukou (LH, or ‘native’) and non-local hukou (NLH, or ‘migrant’) candidates who have applied for the same job, which applicants are more likely to receive an employer contact? Our main finding is that employers on this job board, which caters to private-sector firms seeking relatively skilled workers, prefer workers without a permanent residence permit over equally-matched permanent residents; specifically, there is a difference in callback rates to the same job of about 0.8 percentage points, or 11 percent. This gap is considerably larger in jobs requiring lower levels of education and in jobs offering lower wages. While migrant-native payroll tax differentials might account for some of this gap, we argue that the observed patterns are hard to explain without some role for a migrant productivity advantage over natives, especially in less skilled jobs. Higher levels of migrant productivity could stem from a number of sources, including positive selection of nonlocals into migration, negative selection of local workers into search for the unskilled private sector jobs that disproportionately employ migrants, efficiency wage effects related to unskilled migrants’ limited access to the urban social safety net, and intertemporal labor and effort substitution by temporary migrants that makes them more desirable workers.

In addition to these substantive results, our paper makes three methodological contributions. One is to illustrate the potential of large samples of naturally occurring applications on Internet job boards to study the value of employee characteristics and credentials. Compared to resume audit studies (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004, Oreopoulos 2011, Kroft et al. 2013), job board data let us study large samples of applications and callbacks at a very low marginal cost.Footnote 3 These large samples allow researchers to generate estimates for a more representative set of jobs and to explore match effects between worker and job attributes in a way that is not practical when one is creating and experimentally manipulating resumes. Naturally occurring job board data also avoids the use of fictitious resumes, which can raise issues of credibility in resume audit studies.

Job board data also reveal differences in application behavior between groups, allowing us to estimate the effects of how workers direct their search on their callback rates. For example, we show that migrants’ 11 percent callback advantage relative to equally qualified local applicants to the same job (our analog to the quantity estimated by the resume audit approach) substantially understates their advantage when still controlling for qualifications, but when not conditioning on where they apply. This is because migrants, on average, apply to jobs that are ‘easier to get’ and that pay lower wages relative to their qualifications. More generally, whether workers’ application choices accentuate or mitigate the callback gaps they face within ads has implications for the labor market effects of employers’ callback choices, and cannot be studied with standard resume audit methods.

A drawback of naturally-occurring job board data, of course, is the fact that the resume characteristics we study are not randomly assigned. Thus, if employers base callback decisions on worker characteristics they observe but we cannot hold constant, job-board-based estimates of the ‘pure’ effects of any given resume characteristic may be biased. That said, if we evaluate our approach with respect to the same criterion as resume audit studies—specifically, if the goal is to measure how employers react to specific features of a resume—the scope for omitted variable bias with naturally occurring resumes is relatively limited. This is because callback decisions on a job board (as opposed to hiring or pay decisions) are typically made only on the basis of information contained in a worker’s resume. Thus, the only information about applicants that is observed by employers but not controlled for in our regressions are the features of the worker’s online resume that we have not fully been able to code into our vector of control variables. While such aspects (such as formatting, grammar, unusual types of experience, etc.) certainly do exist, they are probably less important than between-group differences in employers’ expectations of workers’ interview and job performance, which are not eliminated by randomizing group membership on resumes.Footnote 4

A second methodological contribution is to illustrate the importance of the sample of jobs that is used in empirical studies of groups’ relative success in the recruitment process. In particular, job sampling plays a critical role whenever employers (or even jobs) specialize in hiring different types of workers; imagine, for example, a situation where one group of workers has preferential access to ‘good’ (e.g., high wage) jobs, while firms offering ‘bad’ jobs prefer to hire the other worker type.Footnote 5 In such a world, there might be no difference between two groups in their mean chances of getting a job offer, but both the size and sign of the offer or callback gap can depend on the type of job being applied to. Thus, if the sample of jobs surveyed is disproportionately ‘good’ (as it tends to be in existing audit studies) the results will overstate the favored group’s advantage in securing an offer at a randomly selected job. On the other hand, if the sample of jobs is disproportionately ‘bad,’ we might see that the group with worse labor market outcomes overall is preferred by employers. This is arguably what we observe in our data, and it does not necessarily indicate reverse discrimination, or even an absence of discrimination in this labor market. In sum, estimated callback differentials are only relevant to the sample of jobs studied. While this caveat applies both to resume audit studies and to job board studies like ours, it is arguably more important in the former case because of the more restricted sample of jobs for which credible, fictitious resumes can practically be designed.

Third, while it is common to hear claims that employers prefer to hire (say) migrant (or female) workers “because they are cheaper,” to our knowledge no existing studies of the hiring process consider the possible effects on callbacks of expected wage differences between workers who are hired in response to the same job ad. Clearly, if employers expect to be able to pay migrants (or women, or minorities) less, this could affect employers’ callback and hiring choices between two equally qualified applicants in a way that has been hard to assess in existing work. In this paper we take two approaches to bounding the effects of this form of (expected) wage discrimination. One is to distinguish between job ads with and without posted wages (since wage discrimination between worker types is arguably more difficult in posted-wage jobs). The other takes advantage of information on the current wages reported by job applicants on their resumes, which should place some bounds on the wages employers will have to pay to hire these workers. In our case, neither method suggests that within-job wage discrimination against migrants can account for their callback advantage. More generally, resume-based data on current wages help to bound the effects of expected within-job wage discrimination on callback rates: a factor that has been largely ignored in the existing literature.

Section 2 provides some background on China’s hukou system, both nationally and as it applies to our study city. Section 3 describes our data and methods, while Section 4 presents the main results. Section 5 discusses possible explanations of employers’ NLH preferences, while Section 6 concludes.

2 What is Hukou?

Hukou is the legal right to permanently reside in a Chinese province or city.Footnote 6 It is inherited from a parent (historically the mother) regardless of where one is born and is very hard to change. For example, neither long periods of residence in a new location nor marriage to a person of different hukou are sufficient to change one’s hukou. While Chinese workers are de facto relatively free to take jobs in areas where they do not have a permanent residence permit, both state and city governments have created a set of rules that distinguish between local hukou (LH) and non-local hukou persons (NLH) in a number of key markets, including those for housing, labor, education and health. Each province and city government also sets the rules for how migrants can acquire a local hukou.

One main set of legal differences between LH and NLH persons in most Chinese jurisdictions is in eligibility for government-provided benefits and services, especially education and social insurance. For example in our study city, Xiamen, neither LH nor NLH children pay elementary or junior middle school tuition, but LH children have priority in admissions. Seats not filled by LH children are assigned by lottery among NLH children (Xiamen Education Bureau 2010), raising significant barriers for NLH children. Some other cities impose tuition fees on NLH children; together these restrictions lead many NLH workers to leave their children in the care of relatives in their home region, creating a generation of ‘left-behind’ children (Démurger and Xu, 2013).

China’s social insurance programs, which are designed and administered by provincial and city governments, typically provide much lower benefits to NLH workers, but also impose lower payroll taxes on them. In Xiamen during our study period, LH and NLH workers were treated identically in the unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, and childbirth benefits programs, but the two most important social insurance programs—retirement and medical insurance—stipulated lower benefit and tax levels for NLH than for LH workers. At the mean wage in our analysis sample (about 2300 yuan per month), the average payroll tax rate for these two programs together was .31 for locals and .09 for migrants, of which .21 and .05 was paid by employers (and the remaining .10 and .04 by workers). We present additional details on the structure of this tax differential in Section 5, since it could certainly affect employers’ choices between equally qualified LH and NLH applicants.

The second main set of legal distinctions between NLH and LH persons is a patchwork of rules limiting migrants’ access to labor, real estate and some other markets. For example, before and during our analysis period, NLH persons could purchase a maximum of one apartment in Xiamen (General Office of Xiamen People's Government 2013).Footnote 7 In Beijing, NLH workers face barriers in entering the lottery for a car license plate (Beijing Municipal Transportation Committee et al. 2013). A variety of formal and informal restrictions can also affect the types of jobs NLH workers are allowed to take. While variable across cities and often hard to document officially, a number of sources report explicit restrictions on hiring NLH persons as taxi drivers, hotel front desk personnel, lawyers, and in Kentucky Fried Chicken stores in Beijing.Footnote 8 Some state-owned enterprises, as well as provincial and city governments, are claimed to favor LH workers and occasionally will even announce explicit LH quotas.Footnote 9 While we have no hard evidence of such restrictions in Xiamen, employment patterns (described below) suggest that LH preferences may exist for government and SOE jobs there as well.

To provide some context for our analysis, the LH and NLH populations of China’s major cities are described in Appendix 1, which is calculated from 2005 Census microdata.Footnote 10 Statistics specific to Xiamen are also shown. Overall, Appendix 1 documents four key facts that are common to Xiamen and other major Chinese cities. First, NLH persons form a majority of the working population: in Xiamen they constitute 61 percent of the employed population and 70 percent of the private sector workers; in all Tier 1 and 2 cities as a group, these numbers are 57 and 73 percent.Footnote 11 Second, the urban NLH population is much younger and much less educated than working-age natives; for example, 60 percent of Xiamen’s NLH working age residents are age 35 or younger, compared to 39 percent of natives. Sixty-six percent of NLH have at most a junior middle school education (9 years) compared to 46 percent of natives.

Third, urban NLH residents are much more attached to the labor market and work much longer hours than natives. Employment rates (in the working-age population) are 83 percent for working-age migrants compared to 68 percent for natives; one in three employed migrants in Xiamen put in more than 56 hours per week compared to just 12 percent of employed natives. Finally, consistent with the notion that NLH workers face barriers to public sector employment, only 22 percent of employed migrants in China’s major cities work in the broader public sector (government plus State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)), compared to 62 percent of employed urban natives. As we shall argue, this tendency for urban natives to cluster in public sector jobs—which is more muted but still very substantial in Xiamen—provides an important context for our results in this paper, which apply to private sector employers only.

3 Data and methods

3.1 Source and sample construction

With a 2010 Census population of 3.5 million, the city of Xiamen forms the center of a prosperous metropolitan area of 16.8 million people on China’s southern coast. While considerably smaller in population than Beijing and Shanghai, Xiamen’s income levels are relatively close to those cities’, with 2010 GDP per capita at 58,337 yuan, compared to 75,943 and 76,074 yuan for Beijing and Shanghai, respectively. In other respects, Appendix 1 shows that Xiamen is roughly representative of major cities in China; a very similar share of the local population (27-28%) is college-educated, though Xiamen’s population is somewhat younger and the public sector is considerably less important as an employer.

XMRC (http://www.xmrc.com.cn), the job board that is the source of our data, is a for-profit company sponsored by the Xiamen Personnel Bureau (a branch of the local government devoted to the market for skilled labor). Since it was established in 2000, XMRC’s mandate has been to be the main labor market intermediary serving skilled, private-sector workers in the Xiamen metropolitan area.Footnote 12 XMRC operates like a typical U.S. job board, with both job ads and resumes posted online. Workers and firms can contact each other to submit applications, arrange interviews, etc., through the site. According to our conversations with job board executives in other cities, XMRC is nationally recognized for its dominance in Xiamen; national competitors did not attempt to establish a presence there until very recently and have not had much success. In part, XMRC’s dominance in Xiamen’s skilled labor market stems from its stable clientele of local employers, who value good relations with XMRC managers, many of whom are also local government officers. XMRC’s dominance is also facilitated by its physical location within government offices providing employment and social-security related services to employers.

Our analysis sample is extracted from XMRC’s internal database and is designed to represent the inflow of new job ads during a window of time plus all the applications that were ever made to those ads.Footnote 13 Specifically, we asked XMRC to provide us with all the ads for jobs in Xiamen that received their first application between May 1 and October 30, 2010. Then we asked XMRC to provide us with all the resumes that applied to those ads, plus information on all the firms that posted those ads. We also have a mapping of which resumes applied to which ads and a record of which resumes were subsequently contacted by each firm through the XMRC website. Receiving such a contact is our indicator of worker success in the hiring process.Footnote 14 To ensure that we capture all contacts resulting from applications made during our sampling window, we continued to monitor all the ads posted during that window until January 13, 2011 (74 days after Oct. 30 2010). Most contacts occur very quickly, however (within 2 weeks of application). Finally, since our interest is in which workers are selected by firms for interviews or employment, the sample of ads used in this paper excludes ads that never resulted in any employer contacts via the XMRC site.Footnote 15

Other criteria used in constructing our analysis sample include dropping ads with a minimum requested age below 18 or a maximum requested age over 60; ads offering more than 10,000 yuan/month; ads requesting a master’s, professional or PhD degree (all of these were rare); ads for more than 10 vacancies, ads for jobs located outside the city of Xiamen, and ads with missing firm information. We also dropped resumes listing a current wage above 10,000 yuan/month, with missing hukou information or with non-Chinese citizenship, as well as applications that couldn’t be matched to both an ad and a resume. Finally, we dropped a small number of ads for jobs in State-Owned Enterprises and not-for-profit organizations. Despite being a substantial share of employment in Xiamen, ads for SOE jobs are very rare on XMRC, as most recruiting for these positions goes through other channels. Thus our results refer to hiring for private-sector jobs only.

3.2 Descriptive statistics

Our data consist of 221,135 applications made by 78,031 workers (resumes) to 3,489 ads placed by 1,551 firms, resulting in 18,731 callbacks. Thus, a typical ad received about 63 applications, of which 5.4 were contacted by the employer. Means in this sample are presented in Table 1, separately for applications from workers with local and non-local hukou.Footnote 16

As a comparison of Table 1 and Appendix 1 makes clear, applications in our XMRC sample are not representative of Xiamen’s employed population.Footnote 17 Specifically, our sample has a much larger share of young, highly educated, and migrant workers than Xiamen’s 2005 workforce. The much higher levels of education in our sample are consistent with XMRC’s mandate to serve skilled workers, with the massive expansion of higher education in China between 2005 and 2010 (Shen and Kuhn 2013), and with the fact that educated jobseekers are more likely to look for work online than less-educated jobseekers (Kuhn and Mansour, 2014). The high share of young and migrant workers is consistent with the fact that our XMRC data is a sample of job applications, not of employed persons; not only do young workers tend to change jobs more frequently than older workers (Topel and Ward 1992), our data contain a significant share of new labor market entrants. The very high share of migrant applications in our data—91.9 percent (203,239/221,135) compared to migrants’ 70 percent share of Xiamen’s 2005 employed private sector workers—is consistent with a scenario in which migrants search for new jobs on arrival in Xiamen and one where prospective migrants look for work on XMRC while still living elsewhere.Footnote 18

In addition to applicants’ age, education and hukou, our data also include measures of their experience (total years and number of spells), sex, current wage, marital status, height, an indicator for myopia, the number of schools attended, whether an English version of the resume was available, and number of certifications listed. For each application, we also have data on the requirements listed by employers in the job ad, including the desired education, experience, age and gender.Footnote 19 The typical job ad requested about 13 years of education, around a year less than the average education level of the applicants. Over half the job ads stipulated a desired age, with a mean of 27 (about 2.4 years older than the typical applicant). About 59 percent of job ads posted a wage, and the mean posted wage (2,362 yuan/month) is about 4.4 percent higher than the mean current wage listed by workers (2,261) in their resumes. Our data also have an indicator for the number of positions that were available (about 2 on average), and we can measure the number of applications each application is competing with.Footnote 20 Finally, we have indicators of firm ownership, head office location, and size (number of employees) as well as firm identifiers.

While most of the differences between LH and NLH workers and the jobs they are applying to in Table 1 are statistically significant due to the large sample sizes, most of the differences are quantitatively small and in the expected direction for migrant versus non-migrant populations. Specifically, NLH and LH applicants are equally well educated, but are younger, less experienced, more likely to be new graduates, more male, and are less likely to be married than LH applicants. Consistent with being younger, NLH are applying to jobs that request somewhat younger workers and require slightly less experience. Finally, the first row of Table 1 shows that NLH applicants are substantially more likely than LH applicants to receive an employer callback: 7.2 percent of applicants with local hukou are contacted by firms’ HR departments when they apply for a job compared to 8.6 percent for NLH workers, a gap of 19 percent.

3.3 Estimation framework—interpreting recall regressions

To assess whether other observed characteristics can account for the NLH contact advantage in Table 1, we estimate linear probability regressions for contacts as a function of the characteristics of the firm placing the ad, the characteristics of the ad itself (primarily the stated job requirements and the employer’s preferred employee demographics), the match between the job’s requirements and the applicant’s characteristics, the level of other applicant qualifications that are not specifically requested in the ad, and the amount of competition for the job (number of applicants and number of positions available).Footnote 21

Since native and migrant workers are treated differently by the payroll tax system in many jurisdictions, and since it is often claimed that migrants’ lower wage costs make them more attractive to employers, the rest of this section develops an interpretive framework for callback regressions that incorporates possible labor cost differentials, which are not typically considered in studies of the hiring process, including resume audits. As a starting point, we suppose that the probability that an application from worker i to job j receives an employer contact is approximated by the linear relationship:

where q ij is the firm’s expectation of worker i’s productivity in job j based on the contents of the resume, w ij is the wage the firm expects to pay to worker i in job j, t i is the employer portion of the payroll tax for that worker, d measures employers’ net distaste for migrants, M i is an indicator for migrant status (NLH), θ j is an ad-specific expected-quality threshold for contacting a worker, b > 0 is a scaling parameter, and e ij is an iid error term.Footnote 22

Suppose further that

where X ij includes measures of the job’s requirements, the match between the worker’s qualifications and those requirements, plus additional indicators of the worker’s absolute ability. Unobserved employer expectations of how productive the worker is likely to be in the job are captured by ε ij . It is worth noting that ε ij has two conceptually distinct components. One, \( {\varepsilon}_{ij}^1 \), consists of resume features that employers see, but which we have not been able to code into our vector of control variables, X ij . This component is held constant in resume audit studies but not in studies like ours that use naturally-occurring resumes. The second, \( {\varepsilon}_{ij}^2 \), includes both an iid component of match quality and employers’ forecasts of employee productivity from resume characteristics, X ij and M i . These forecasts are not held constant in either estimation approach. Importantly, then, both our results and those of resume audit studies are best interpreted as estimates of how employers react to resumes, where those reactions include both employer tastes and forecasts (whether biased or unbiased) of future productivity based on observable features of the resume.

We describe employer payroll taxes by:

where Δ t = t N − t M ≥ 0 is migrants’ payroll tax advantage.

Finally, the effect of expected wages on the callback decision depends on the firm’s wage-setting process. To explore this, we consider two cases, beginning with the case of posted wages (Doeringer and Piore 1971; Burdett and Mortensen 1998; Lang et al. 2005).

3.4 Case 1: Posted wages

If wages are completely tied to jobs, expected wages can be written as:

In this case, workers who are hired in response to the same ad must be paid the same wage. This assumption is typically maintained (either explicitly or implicitly) in resume audit studies, since otherwise the studies would not be informative about employers’ preferences

Substituting (2)-(4) into (1), the callback probability in Case 1 can be expressed as:

A key insight from (5) is that ad fixed effects, \( b\left[{\overline{w}}_j+{\theta}_j\right] \), will absorb any differences across firms and jobs in hiring standards, θ j . More importantly, while it seems intuitive that employers might prefer migrants “because they are cheap,” equation (5) makes it clear that the sizable native-migrant wage differentials that are measured in regression studies of Chinese survey data are not for the most part relevant to the callback gaps estimated in this paper.Footnote 23 This is because all native-migrant wage gaps associated with the possibility that migrants disproportionately apply to (and ultimately work in) low-wage jobs are also absorbed in our ad fixed effects, \( b\left[{\overline{w}}_j+{\theta}_j\right] \).

Summarizing Case 1, we have:

3.5 Result 1: The migrant-native hiring gap when wages are attached to jobs

When two workers who are hired in response to the same job ad must be paid the same wage, the estimated migrant-native callback gap in the presence of job ad fixed effects will be given by:

where ∂ε ij /∂M i is the partial regression coefficient of unobserved applicant quality on migrant status, controlling for all the remaining observables in (5).■

In sum, when wages are attached to jobs, the employer share—and only the employer share—of payroll taxes affects which workers we expect firms to pick from an applicant pool. In consequence, the estimated coefficient on M i in the presence of ad fixed effects reflects the net impact of three factors: employers’ tastes for hiring migrant workers, −bd, which we expect to reduce migrants’ callback rates; migrants’ payroll tax advantage, bΔ t, which we expect to raise migrants’ callback rates; and any uncontrolled migrant-native differences in expected productivity, b ∂ε ij /∂M i .

3.6 Case 2: Adding within-job wage differentials

To see how the above conclusions change when there is wage variation between workers who have been hired for the same job, we consider two possible sources of within-job wage variation. The first corresponds to shifting of the employer portion of the payroll tax onto workers. To incorporate within-job tax shifting, we replace (4) by:

where \( {w}_{ij}^{*} \) is the wage that would be paid in the absence of a payroll tax and 0 ≤ φ ≤ 1 is a pass-through parameter. If φ = 1, the entire employer portion of payroll taxes is passed on to workers in the form of lower wages, while φ = 0 corresponds to zero pass-through.Footnote 24

If taxes are described by (3) it follows that

According to (8), the effect of within-job shifting of employer payroll taxes is to reduce natives’ wages below migrants’, since part of natives’ higher employer tax cost is now passed on to them. One way this might occur is if wages are bargained after a hiring decision is made, as in Mortensen and Pissarides (1994), a situation which is more common in skilled jobs (Brencic 2012). Another possibility is that firms advertise a wage that is appropriate for one class of worker (say, NLH), with the understanding that LH applicants are expected to accept a lower wage to compensate for their higher tax costs.Footnote 25

A second possible source of within-job wage differentials for new hires is related to employer monopsony power. If, on average, migrants have less attractive labor market alternatives than natives, employers in a world without payroll taxes might be able to pay migrants less than equally-productive natives (Hotchkiss and Quispe-Agnoli 2009, Depew et al. 2013, Hirsch and Jahn 2015). To model this, let the baseline wage, \( {w}_{ij}^{*} \), in (7) equal \( {w}_j^{N*} + {\nu}_i \) for natives and \( {w}_j^{M*} + {\nu}_i \) for migrants, where ν i captures idiosyncratic worker bargaining power that is uncorrelated with migrant status. It follows that

where \( {\varDelta}^{w*}={w}_j^{N*}-{w}_j^{M*} \) is the monopsony-related cost advantage of hiring migrants, which is positive if migrants have worse outside options. Combining (8) and (9) yields:

In this more general setting, the wage the employer expects to pay is the sum of a job-specific intercept \( \left[{w}_j^{N*}-\varphi {t}^N\right] \) a term representing idiosyncratic worker wage bargaining power ν i , and a within-job migrant wage differential (φΔ t − Δ w *)M i . This latter term represents the net impact of shifting of employer tax rates onto workers (which tends to raise migrants’ wages relative to natives) and a monopsony effect, which we expect to have the opposite effect.

Substituting (10) into (1) yields:

Summarizing Case 2,

3.7 Result 2: The migrant-native hiring gap with within-job wage differentials

When two workers who are hired in response to the same job ad can be paid different wages, the estimated migrant-native callback gap in the presence of job ad fixed effects will be given by:

Compared to (6), (12) has two additional terms reflecting the effect of within-job wage differentials (if any) between natives and migrants. One of these, bΔ w *, is the effect of any additional monopsony power employers might have over migrant workers, due to their poorer labor market alternatives. Any such power should reduce the wage employers expect to pay migrant workers relative to natives, thereby raising (i.e., helping to explain) migrants’ callback advantage. The other, − bφΔ t, reflects shifting of natives’ payroll tax disadvantage into the wages paid to natives. Any such shifting should increase migrants’ relative wage costs (compared to the posted-wages baseline), thereby reducing (i.e., making it harder to explain) migrants’ callback advantage. In the following section, we shall argue that it is possible to bound the relative magnitude of these two factors by looking at data on the current wages of job applicants. Notably, as is formalized in equation (12), a situation where these two factors just balance each other is observationally identical to the much simpler case where wages are tied to jobs (Case 1).

4 Results

Table 2 presents linear probability estimates of equation (11), where the dependent variable equals one if the applicant was contacted by the firm’s HR department after applying to the ad.Footnote 26 Column 1 contains no regressors other than NLH; it replicates Table 1’s finding that, on average, NLH workers were 1.4 percentage points (or 19 percent) more likely to receive an employer contact than LH workers.Footnote 27 Column 2 adds controls for basic characteristics of the job ad (specifically the requested levels of education, age, experience, gender, and whether a new graduate or technical school graduate is sought) plus measures of the match between those characteristics and the worker’s actual characteristics X ij . Also included are controls for the advertised wage, the worker’s gender, and the worker’s technical school and new graduate status. Column (2) shows that workers who are older than the job’s preferred age range and of a different gender than the firm requests are significantly less likely to receive a callback than workers who meet these hiring criteria.

Column 3 adds controls for a more detailed set of CV characteristics that are available in our data. These are whether the applicant attended a technical school, the applicant’s zhicheng rank (6 categories), whether the CV is in English, the number of schools attended, the number of job experience spells, and the number of certifications reported.Footnote 28 The following characteristics are also included, both as main effects and interacted with the applicant’s gender: myopia, height, and marital status. Occupation fixed effects (for the job) are added in column 4. Column 5 adds two indicators of the amount of competition for the job in question, specifically the number of positions available and the number of persons who applied to the ad. Both of these indicators have strong effects in the expected directions; adding them increases the estimated NLH effect somewhat. Overall, however, between columns 1 and 5 there is some attenuation in the NLH coefficient as controls are added, reducing the size of the estimated effect from 1.38 percentage points in column 1 to 1.13 percentage points in column 5. Intuitively, this attenuation is accounted for by the fact that NLH workers apply to jobs to which they are somewhat better matched (column 1 to 2) and are slightly more qualified in terms of detailed resume characteristics (column 3).Footnote 29

Column 6 replaces the occupation fixed effects by fixed effects for job cells, defined as the interaction of firms and (requested) occupations. Thus, column 6 compares observationally identical LH and NLH workers who have applied for a job in the same occupation in the same firm (though not necessarily in response to the same ad). This reduces the estimated size of the NLH effect substantially (to 0.81 percentage points). It follows that part of the unadjusted NLH advantage in column 1 (at least (.0113-.081)/.0138 = 23 percent) results from a tendency for NLH workers to disproportionately apply to job cells with higher overall callback rates.Footnote 30 Thus, as argued earlier, group differentials in callback rates depend on the sample of job ads that is considered; in our case the overall callback advantage of NLH workers is explained, in part, by the fact that they disproportionately apply to jobs that are “easier to get”.

Our most saturated specification in column 7 replaces column 6’s job cell fixed effects with a full set of job ad fixed effects, thus effectively comparing the success rates of LH and NLH workers who have applied to the same ad. As noted earlier, column 7’s fixed effects absorb any wage that is attached to the job as well as job-specific hiring standards. These estimates are identified only by the sample of job ads that received at least one NLH applicant and one LH applicant. Compared to column 6, they leave the NLH coefficient essentially unchanged. An interesting feature of columns 6 and 7 is that several indicators of job-worker mismatch (specifically whether the worker is less educated than requested, younger than requested, and less experienced than requested) that were insignificant in less saturated specifications are now associated with highly significant reductions in callbacks. Part of this effect is due to a reduction in standard errors relative to columns 2–5, suggesting that focusing on within-ad competition for jobs improves the precision of our estimates.

Comparing columns (1) and (7), the NLH coefficient attenuates by .58 percentage points (.0138 - .0079) between columns 1 and 7, which might be a cause for concern if there are important features of workers’ resumes we have not adequately been able to code into our control variables. Importantly, however, note that only .13 points (or 22 percent) of this attenuation (i.e., the gap between columns 2 and 3) results from adding finer controls for resume characteristics. The remainder results from increasingly detailed controls for where applicants are directing their applications. Thus, as argued earlier, naturally occurring job board data provides information on how overall gaps in job search success between groups of workers are affected by those workers’ directed search strategies. According to Table 2, the within-job hiring gap of .8 percentage points in column (7) understates the aggregate gap of .14 percentage points in column (1) because migrant workers choose to target their job applications less aggressively than local workers, focusing on jobs that are, on average, ‘easier to get.’ From a welfare point of view, it is not clear whether column (1) or column (7) is more relevant.

In sum, Table 2 presents evidence that NLH workers have a higher chance of receiving an employer callback than observationally-equivalent LH workers when both groups of workers are competing for the same private-sector job. In our most saturated specification, NLH workers have a callback advantage of 0.8 percentage points, or 11 percent, an effect which is highly statistically significant. In the following section, we consider the plausibility of various explanations for this gap by exploring how the size of the gap varies across types of ads, firms and workers.

5 What explains firms’ preferences for NLH workers?

According to equation (12) there are four broad types of factors that could explain NLH workers’ callback advantage: employers’ tastes (−d); the direct effect of LH workers’ higher payroll taxes, Δ t; within-job wage gaps between LH and NLH workers (Δ w * − φΔ t); and the possibility that migrants are on average more productive than observationally identical natives (∂ε ij /∂M i ). The first of these is not a likely explanation of the NLH callback advantage, since available evidence from other sources suggests that if anything Chinese urban residents are either indifferent or have some distastes for interacting with non-local workers (Dulleck et al. 2012). In the remainder of this section, we draw on various pieces of evidence to attempt to assess the importance of the remaining three.

5.1 Payroll tax differentials

If NLH workers’ payroll tax advantage is the main explanation of their higher callback rate, one would expect their callback advantage to be most pronounced in situations where their payroll tax advantage is the greatest. To pursue this idea, note that during our sample period employers of LH workers in Xiamen paid 21 percent of the worker’s monthly salary (with a minimum and maximum basis) to city’s retirement and health insurance programs. For NLH workers, these contributions were set at a fixed, low amount that is unrelated to the worker’s wage rate. The exact formulas and their consequences for average tax rates at typical salaries in our sample are shown in Appendix 2, which shows a roughly constant employer tax rate gap of about 19 percent between the two worker types across the entire wage distribution in our sample (column 3). The absolute tax differential in column (4), on the other hand, increases with earnings. Both these properties also apply to total (employer plus employee-paid) taxes (in columns 5–8). Thus, depending on whether the total tax difference (in yuan) or the difference in tax rates is most relevant to employers’ callback decisions, NLH workers’ payroll tax advantage is either increasing or roughly constant across job skill levels.

To see if NLH workers’ callback advantage conforms to either of these patterns across skill levels, Table 3 estimates a different effect of NLH status on the callback rate for four levels of required education, while Table 4 does the same for four advertised wage bins. For both wages and education levels we find the opposite pattern from what is predicted by NLH workers’ payroll tax advantage: firms’ revealed preferences for NLH workers are considerably stronger at low skill levels than higher ones. With respect to education, the NLH advantage is strongest—at 1.7 percentage points—in jobs requiring junior middle school (9 years of education), much smaller (0.9 points) in jobs requiring senior middle or tech school, 0.6 percentage points in college-level jobs, and small and insignificant for university-level jobs. For advertised wage levels, the trend is similar: the NLH hiring advantage is highly statistically significant, at 1.4 percentage points, in jobs advertising a wage below 2,000 yuan per month, half that size in jobs paying 2,000-4,000 yuan per month, and absent at higher wage levels.

Overall, the fact that the NLH hiring advantage in our data is strongly concentrated among less-skilled and low-paid jobs is inconsistent with a scenario in which statutory payroll tax differences between LH and NLH workers are the only explanation of the callback gap.Footnote 31 At a minimum, one or more additional factors, which disproportionately make less-skilled NLH workers more attractive to employers, must also be at work. We discuss a number of such factors in the remainder of this section.

5.2 Within-job wage differentials

Equation (12) indicates that NLH workers’ relative callback rates should also depend on any expected wage differentials between NLH and LH workers who are hired in response to the same job ad. If within-job wage gaps primarily reflect payroll tax shifting, we would expect natives to be paid less than migrants; this would reduce the relative attractiveness of migrant workers and cancel out some or all of the direct effect of employer-paid payroll taxes. On the other hand, if monopsonistic wage discrimination against migrants dominates, we would expect natives to be paid more than migrants, which would raise migrants’ relative attractiveness. If these two factors roughly cancel each other out, or if within-job wage discrimination is not possible, we should not see within-job wage gaps between natives and migrants, and they cannot help us explain the NLH callback advantage.

We do not, of course, observe whether employers expect or plan to pay different wages to LH and NLH workers who apply to the same job in our data. Still, two features of our data help us place some bounds on the likely effects of these types of wage gaps. One is that we can distinguish between job ads that did or did not post a wage; if it is harder to wage discriminate between worker types when a wage is posted in the job ad we should see a different callback gap in the two types of jobs. (The sign of the difference depends, again, on Δ w * − φΔ t). To see if this is the case, we estimated callback regressions that interact the NLH effect with whether the job ad posted a wage.Footnote 32 No statistically significant interaction effects were estimated in any specification. Second, recall as Table 1 indicates that almost 70 percent of applicants list a current wage on their resume. If the wage currently earned by a job applicant is a rough lower bound for what a firm must pay to hire that applicant, the current wage will give us some indication of the scope available to employers to pay different wages to NLH and LH workers who have applied to the same job.

Table 5 presents NLH coefficients from the same regressions as our main results (in Table 2), but where the dependent variable is the log of the worker’s current wage as listed on their XMRC profile. To allow us to focus on the job types where the NLH hiring advantage is present, Table 5 estimates separate applicant wage differentials for jobs requiring below versus above 12 years of education, and for jobs posting a wage below versus above 4,000 yuan per month. Focusing first on the raw data in column 1, we see (as one might expect) that NLH workers applying to less skilled and low paying jobs have current wages that are below those earned by native applicants. Interestingly, the opposite is true for NLH workers applying to highly skilled, high paying jobs. NLH university graduates seeking work in Xiamen have very good current jobs compared to Xiamen’s local university-educated applicants.

More importantly, comparing equally-qualified workers who have applied to the same jobs (which is the relevant comparison for understanding our main result), column 7 shows a very different pattern. In applicant pools for skilled jobs, the current wages of NLH applicants are the same as those of native applicants. In applicant pools for unskilled jobs, however, the current wages of NLH applicants are two to four percent higher than natives. Again, this is because migrants target their applications a little less aggressively (in terms of wages relative to their current wage) than natives. The implication for employers of less-skilled workers on XMRC is that employers who want to match the wages their applicants are currently earning elsewhere would need, on average, to pay a migrant two to four percent more than natives. This strongly suggests that lower migrant wages within jobs are an unlikely explanation of the NLH callback advantage. Further, such a two to four percent wage discount for natives contrasts with a direct additional employer payroll tax bill (from Appendix 2) of 16 to 19 percent. Thus, it seems highly unlikely that firms will be able to pay natives sufficiently less than migrants within jobs to undo migrants’ payroll tax advantage.

In sum, if applicants’ current wages set meaningful constraints on what firms must pay to hire workers, within-job wage discrimination against migrants is not a likely explanation of the NLH hiring advantage. Applicants’ current wages also suggest that within-job payroll tax shifting onto natives would not be able to undo much more than a small fraction of natives’ higher direct payroll tax costs. Together, this means we can largely ignore the component of GAP 2 related to within-job wage differentials, b(Δ w * − φΔ t), leaving only the direct effect of employer payroll taxes and productivity differentials as remaining candidate explanations for the NLH callback advantage.

5.3 Productivity gaps—selection

We now turn to the final term in equation (12): the possibility that employers expect migrants to be on average more productive than observationally identical natives when making callback decisions (∂ε ij /∂M i > 0). We can think of a number of reasons why this might be the case and can only provide a few pieces of evidence regarding which ones might be most relevant. Sources of migrant-native productivity gaps fall into two main categories, the first of which is selection, i.e., uncontrolled productivity differentials that are time-invariant features of the employee.

One possible source of differential selection is the notion that NLH migrants may be perceived by employers as being positively selected relative to their compatriots who chose to remain behind in poorer parts of China (Borjas 1987). An important caveat to this explanation, however, is the fact that positive selection relative to stayers in the origin region does not imply positive selection relative to natives in the destination city. Indeed, if anything, we would probably expect NLH workers to suffer deficits relative to LH workers in education quality, connections (guanxi) and other destination-specific skills, which would all appear as negative selection on unobservables in our regressions. Thus, positive selection of out-migrants from other provinces can only explain our main result if it outweighs these likely skill disadvantages.

A second type of selection that could account for our result is negative selection of LH workers into formal search for private-sector jobs on XMRC. Is it possible that LH workers who choose to look for work in Xiamen’s private sector are on average less able than the typical LH worker? Evidence on selection into SOEs from the period before Premier Zhu’s “letting go of the small” SOE reforms in the late 1990s actually suggests the opposite: at that time the nascent private sector attracted workers who were more ambitious and risk tolerant (He et al. 2014). Since those reforms, however, SOE jobs have become much scarcer and pay well relative to urban private sector jobs (Du and Wang, 2013). Thus, it is possible that the subset of Xiamen’s LH workers who are looking for private sector work on XMRC during our sample period are negatively selected (in the same way that U.S.-born workers who apply to low-wage jobs occupied mostly by temporary migrants may also be negatively selected). If so, that could account for the NLH callback advantage in our data.

5.4 Productivity gaps—hours and effort

The other potential source of migrant-native productivity gaps is different choices made by workers of the same ability. Here, the most likely candidates are effort and labor supply decisions that make migrants more desirable to employers.Footnote 33 One commonly-cited reason for such oft-cited “immigrants work harder” effects is an efficiency wage effect: to the extent that migrants’ outside options are poorer than natives’, migrants should be willing to exert more effort to keep their jobs. Two of our key results in this paper, however, are inconsistent with this idea. One is the fact that the current wages listed by NLH workers on their resumes are higher than those of natives who applied to the same ad, especially in jobs with low skill requirements (where the NLH hiring advantage is concentrated). The other is the paper’s main result: NLH workers searching for work on XMRC have higher recall rates than urban natives, so they should have an easier time finding alternative employment. These caveats noted, however, there may be some outside options not visible in our data that are better for LH workers than migrants. Such options include better access to the urban social safety net (documented in Appendix 1), higher nonlabor income (including apartment rentals), and preferred access to attractive, secure public sector and SOE jobs. It is possible that these outside options reduce natives’ work incentives, thereby making them less attractive to private sector employers.

The second reason why effort and hours choices might differ between natives and migrants is intertemporal labor supply substitution: to the extent that NLH workers come from, and expect to return to a lower-wage region of origin, NLH workers have an incentive to reallocate work hours and effort from other stages of their lifetime into the time they are in the destination city (Dustmann 2000). If employers prefer workers with such higher attachment to work, the intertemporal labor substitution hypothesis predicts that employers should prefer NLH workers from poor provinces to NLH workers from rich provinces (since workers from poor provinces have lower wages at other points in their life cycle). Note that this prediction contrasts with what we might expect from simple human capital models, which suggest that the lower quality of education, poorer health, and lower familiarity with modern work practices in poorer regions would hurt those residents’ employment prospects in Xiamen.

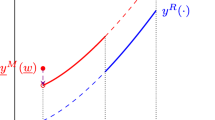

To explore this prediction, Fig. 1 plots the unadjusted NLH advantage in our data against the mean GDP per capita in an NLH applicant’s province of hukou. It shows very high callback rates for applicants from China’s two poorest provinces—Guizhou and Yunnan—, low callback rates from richer areas like Guangdong and Inner Mongolia, and very few applicants to jobs in Xiamen from the richest areas: Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin. The linear regression line in the Figure shows a clear negative relationship between per-capita GDP in the sending region and workers’ callback rates from employers in Xiamen. To quantify this relationship, Table 6 adds four regressors to the specification in Table 2. The first is a fixed effect for whether the NLH applicant is not from Fujian (the province in which Xiamen is located); this allows us to see whether interprovincial applicants, as a group, are treated differently from intraprovincial ones. The next two variables interact interprovincial migrant status with the railroad distance of the applicant’s home province from Fujian and its level of per capita income. Among other things, distance might affect the chances an applicant would accept the job offer if he applied while living in the hukou province. Finally, we add a control for the migrant’s current wage (i.e., the dependent variable in Table 5) to isolate the effect of coming from a poor region (as distinct from having different labor market alternatives in the destination city).

Consistent with an intertemporal labor supply interpretation of the NLH advantage, row 3 of Table 6 shows that the NLH callback advantage decreases with the origin province’s per capita GDP, reflecting the pattern in Fig. 1. While not statistically significant in every specification, this effect is significant (at 5 percent) in the absence of controls (column 1) and (at 10 percent) in our most saturated specifications (columns 6 and 7), which control for job cell and job ad fixed effects respectively. While hardly definitive, we see Table 6’s results as supportive of the intertemporal labor supply hypothesis.Footnote 34

5.5 Why is the NLH callback advantage absent at higher skill levels?

So far we have argued that payroll tax and expected productivity differences are the most likely causes of the NLH callback advantage in our data. Neither of these hypotheses on their own, however, can account for the fact that the NLH callback advantage is only observed in the less-skilled jobs posted on XMRC: the tax hypothesis predicts either a constant or increasing NLH callback advantage with skill, and so far we have not provided any reasons why NLH workers’ productivity advantage might be confined to less skilled workers. In this final subsection we discuss a number of factors that might attenuate NLH workers’ tax and productivity advantages at high skill levels relative to lower skill levels.

In our review of China’s hukou system, we noted that some Chinese cities make it easier for skilled workers than unskilled workers to acquire a local hukou. If this type of hukou conversion is sufficiently quick and common among skilled NLH workers, it could eliminate the tax and efficiency wage advantages of hiring them, compared to skilled LH workers. Data from the 2005 Census, however, suggests that hukou conversion rates within the first five years of residence in a new location are very low, even for college graduates: 87 percent of young, urban college graduates who lived in a different location five years before the Census date did not have their hukou in their current city.Footnote 35 Thus it seems unlikely that hukou conversion can explain why the NLH callback gap is absent at high skill levels.

Another possibility is income effects of the much more generous education, health and retirement benefits available to LH than NLH workers. Since these income effects are likely to be more important for unskilled workers, they could disproportionately reduce LH workers’ hours and effort levels at low skill levels, making them less attractive to employers than unskilled migrants who are not entitled to these benefits. The intertemporal labor substitution effects discussed in Section 5.4 will be also stronger for unskilled migrants than skilled migrants if, as seems likely, their wages in Xiamen differ more from their home-province wages than do the wages of skilled migrants. Finally, and perhaps most likely, there may be production complementarities between skill and local experience. If knowing that a worker comes from and will remain in the city is more important to employers of skilled than unskilled workers, this will favor skilled LH workers in the competition for callbacks. Put another way, employers of skilled workers may care more about long term relationships and location-specific skills, and be less interested in the cost savings or higher short-term effort levels associated with hiring temporary migrants.

6 Conclusion

To our knowledge this is the first paper to study employers’ hiring choices between equally-qualified workers with and without permanent residence permits in the region of employment. Our main finding is that despite other evidence of taste-based discrimination against persons without permanent status (NLH) in China’s cities, and despite the fact that NLH workers likely have lower levels of destination-specific skills than natives, employers in our data are more likely to call back identically-matched NLH than LH applicants to the same job. Further, this preference for migrant workers is confined to situations where firms are seeking to fill less-skilled and lower-paid positions.

What might account for migrant workers’ estimated callback advantage in our data? Since the advantage is confined to less skilled positions, we argue that employers’ payroll tax savings on NLH workers (which are either skill neutral or favor skilled NLH workers) cannot be the only explanation, suggesting that temporary migrant workers may have a productivity advantage over natives in less skilled and low paid jobs. Possible sources of such an advantage include differential selection of LH and NLH workers into active search for low-skilled private sector urban jobs, and different effort and labor supply decisions while in the destination city. For example, preferred access to secure, well paid SOE and public sector jobs and greater coverage by the urban social safety net could reduce less-skilled LH workers’ work incentives in a way that makes them less attractive to private sector employers. At the same time, intertemporal labor substitution effects might account for high observed levels of hours and effort among temporary migrants, making them more attractive to employers. These and other sources of a migrant productivity advantage will be muted in jobs with higher skill requirements if, as seems plausible, skill is complementary with LH workers’ local labor market experience, connections and knowledge. We stress that the above are only possible sources of a migrant productivity advantage in low paid jobs and that much additional work is needed to understand the source and robustness of such an advantage.

While we believe that our findings are thought-provoking, we also emphasize that they should be interpreted with a number of important caveats in mind. One is the fact that—as in all correspondence studies—our dependent variable measures callbacks only, not whether a worker ultimately receives a job offer. As a result, our main result could be in jeopardy if firms systematically make fewer offers per callback to NLH than LH workers, provided they do this more at low skill levels than high ones. While we cannot rule this out, it is hard to think of plausible reasons why callback and offer patterns might differ in this way.Footnote 36

Second, recall that our data are for private-sector jobs exclusively; thus, our results say nothing about the preferences of public-sector employers and state-owned enterprises, which according to the 2005 Census account for a majority of the jobs held by LH workers in China’s major cities.Footnote 37 Indeed, since public sector and SOE jobs are sometimes explicitly reserved for LH workers, our results are consistent with a segmented labor market scenario in which—holding match quality fixed—private-sector employers tend to prefer NLH workers, while public service and SOE employers give preference to LH workers. Indeed, the latter sectors, which are generally not exposed to significant competitive pressures in product markets, may play an important role in sheltering native workers from competition with the massive influx of migrants in many Chinese cities.Footnote 38

Finally, we emphasize that the unique nature of China’s hukou system clearly limits the relevance of our results to workers with insecure or limited residency rights in other jurisdictions. For example, unlike unskilled temporary migrants in the U.S. (many of whom are undocumented), NLH workers are not at risk of summary deportation. And unlike H-1B visaholders who are subject to U.S. Social Security and Medicare taxation (Thibodeau, 2010), skilled NLH workers pay different payroll taxes than their native counterparts. Still, in the Chinese context, our results suggest quite strongly (and perhaps paradoxically) that—at least at low skill levels—learning that a worker has limited residency rights in a city appears to make that city’s employers more interested in hiring that worker.

Notes

For recent examples of both these claims, see Nir’s (2015) description of the labor market for nail salon workers in New York.

In part, this is because very few databases include information on individuals’ residency or visa status. Oreopoulos (2011) studies Canadian employers’ choices between natives and persons with Asian-sounding names, but the latter are predominantly permanent residents.

Likely for cost reasons, resume audits tend to use quite constrained samples. Both Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) and Kroft et al. (2013) restrict their attention to four occupations: sales, administrative support, clerical, and customer service. Oreopoulos (2011) considers more occupations, but restricts his attention to jobs that required three to seven years of experience and an undergraduate degree, and to applications that possess those qualifications.

While it is possible to shed some light on the role of these expectations by manipulating the amount of information contained in resumes, both our approach and resume audit studies are probably best interpreted as estimates of how employers ‘read’ resumes, i.e., as estimating the effects of learning that a person belongs to a certain group on the probability of giving the worker a callback.

The simplest example of such a model is Becker’s (1971) model of taste-based employer discrimination. In that (frictionless) model, employers have heterogeneous distastes for interacting with one of the two worker types. An equilibrium wage gap clears the market and workers are segregated by type across employers. While neither group has a hiring advantage overall—in the sense that both will be hired for sure if they apply to the ‘right’ job—, the disfavored group will be turned away from the ‘good’ (high wage) jobs, and the favored group will be turned away from the bad jobs if they apply there.

Such restrictions could impact the labor market via income effects from the apartment rental market, which is reportedly an important income source for many LH persons.

See Li (2010) regarding lawyers and Standing Committee of the Beijing Municipal People’s Congress (2002) regarding taxi drivers. Hukou-based requirements for hotel front desk personnel and KFC employment have been claimed by a number of commentators on social media.

Aluminum Corporation of China (2012) is an ad for new college and university graduates placed by a large SOE. The company advertises an explicit recruitment quota of 30 percent LH and 70 percent NLH, but adds the following note at the bottom of the ad: “Note: Beijing students, education can be relaxed”.

“Major cities” are the four cities under direct central government control (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing), plus the fifteen sub-provincial cities, which include Xiamen. These city groups are sometimes referred to informally as China’s “Tier 1” and “Tier 2” cities.

70 and 73 percent are the NLH share in private enterprises (the main employers on the XMRC job board) implied by the employer type distribution in Appendix 1.

Recruiting for public sector and SOE jobs occurs via other channels. Recruiting for unskilled workers takes place primarily via XMZYJS (the Xia-Zhang-Quan 3-city public job board www.xmzyjs.com), which is the only other major job board based in Xiamen. XMZYJS is operated directly by the Xiamen Labor Bureau, a local government department focusing on unskilled workers. It does not post worker resumes and does not provide a mechanism for firms and workers to contact each other through their website.

This approach eliminates the problem of length-biased sampling that would apply to a sample of the stock of ads on the site during an interval of time.

Since only about 8 percent of applications in our sample result in employer contacts, we interpret these contacts as a relatively strong interest on the firm’s part in hiring the worker. Conversations with XMRC officials support this interpretation, as does evidence in all our regressions (detailed below) that the probability of contact is strongly and positively related to the quality of the match between workers’ characteristics and the job’s advertised requirements.

No contacts could mean the firm didn’t hire during our observation period, or they contacted successful workers using means other than the job board.

LH in Table 1 and throughout our main analysis denotes Xiamen city hukou only; workers with Fujian province (but not Xiamen) hukou are treated as NLH because their legal status in the city is the same as workers from other provinces.

Unfortunately, 2005 is the most recent Chinese Census data available to us.

While we know the location of our applicants’ hukous, our confidentiality agreement with XMRC prevents us from knowing where applicants are located when they apply to jobs on the website.

See Kuhn and Shen (2013) and Delgado Helleseter, Kuhn and Shen (2014) for an analysis of explicit gender targeting in Chinese job ads, which is quite common.

An average application was competing with about 189 others in our sample. Note that this is a different concept than the number of applications received by a typical ad, which we have already noted is about 64.

We use linear probability models rather than, say, probits, because our most saturated specifications use large numbers of fixed effects (one for each job ad), raising computational issues as well as concerns with consistency in the presence of a large number of incidental parameters.

Only the employer portion of the payroll tax enters equation (1) because the equation controls for the wage that is paid to the worker. This does not rule out shifting of the employer tax onto workers via endogenous adjustments in wages. In particular, if employers pay higher taxes on LH workers and some or all of that tax differential is shifted onto them, wages for LH workers will be reduced relative to NLH workers. This would be reflected in a lower value of w ij in (1), which has the effect of canceling out some or all of the effect of LH workers’ higher tax rate on firms’ hiring decisions. We discuss how the interpretation of our results depends on assumptions about tax shifting below.

Survey-based studies of the migrant-native wage gap in China include Meng and Zhang (2001), Lu (2008) and Xing (2014), all of whom find that migrants earn less than natives in urban China even after controlling for the usual observable worker characteristics. Importantly, however, Meng and Zhang, among others, find the gap is substantially reduced when controls for employer type (specifically, public sector and SOE) are introduced.

In addition to institutional factors, the amount of pass through may also depend on how much workers value the public health and retirement benefits their higher taxes buy (Summers 1989). For example, if LH workers place a high value on these benefits, employers will find it easier to ask them to accept a lower wage than migrants who are not entitled to the same benefits. The only effect on our analysis is on the value of, since employers care only about the relative wages, tax costs, and productivity of two workers when choosing whom to hire for the job.

Adjusting wages to shift employer taxes onto workers is illegal in Xiamen, though it is unclear how strongly this prohibition is enforced.

Applications that were contacted via methods other than the website (such as telephone) are treated as not being contacted in our data. This could be an issue if firms tend to use different methods to contact LH versus NLH workers. We explored this issue in discussions with XMRC officials, who stated that this was highly unlikely. The marginal financial cost of contacting an applicant anywhere in China is zero both by telephone and via the site, and recruiters generally find it easiest to issue all callbacks to the same job in the same way.

The standard errors in Table 2 adjust for correlation among applications to the same ad by clustering on ads; this handles a substantial share of the likely error correlations in our data since the typical ad received about 63 applications. To explore the effects of within-applicant error correlations on the significance of our estimates (which are likely much smaller since the average resume applied to only 2.8 jobs), we replicated our main results on a sample consisting of one randomly-selected application from each worker. There was very little change.

Zhicheng is a nationally-recognized worker certification system that assigns an official rank (from one through six) to workers in almost every occupation. While education and experience play key roles in many occupations’ zhicheng ranking schemes, several professions also use government-organized nationwide or province-wide exams both to qualify for and to maintain one’s zhicheng rank.

The column 5 coefficient is essentially identical to the column 3 coefficient because NLH apply to higher-callback occupations (column 4), but to individual ads where there is more competition for the job (column 5).

Some search models of discrimination, such as Lang, Manove and Dickens (2005) have the property that in equilibrium, groups that anticipate encountering discrimination in the hiring process direct their search towards lower-wage jobs, which may be easier to get.

Some commentators on this paper have suggested that payroll tax noncompliance among employers of unskilled NLH workers might help account for those workers’ stronger NLH callback advantage. The very low statutory NLH tax rates in Table 1, however, imply that even complete noncompliance (zero taxes) among migrants’ employers would not substantially alter the skill profile of the NLH tax advantage.

Admittedly, this is a rather weak test since our wage measures come in bins that are quite wide. This would leave considerable room for negotiation within a pre-announced wage bin.

In general, firms will prefer workers who choose higher effort levels, or who will accept additional work hours, whenever employment contracts are incomplete, i.e. as long as the pay rate per hour or piece gives workers less than 100% of the surplus they generate at the margin.

Consistent with the notion that employers must match applicants’ current wages, Table 6 also shows that ceteris paribus, workers with high current wages are less likely to receive employer callbacks.

Statistics refer to 18–35 year old college graduates currently living in a city and employed in the private sector. The comparable rate for movers with high school or lower education is 99 percent.

A key source of the difficulty is that most unobserved factors that could affect callback rates should theoretically affect offer rates conditional on callbacks in the same direction. For example, suppose (as seems likely) that NLH workers’ productivity is harder to predict than natives. In that case, their higher option value suggests that employers should not only interview more of them, but make more job offers to them as well (Lazear 1995). The same should apply if NLH workers are more likely to accept a job offer than LH applicants: both callbacks and offers should be higher, with no clear prediction for the ratio of offers to callbacks.

See Appendix 1: the share is 62 percent.

House (2012) documents a similar, though more extreme phenomenon in Saudi Arabia, where 90 percent of private-sector jobs are held by foreigners, while natives either work in the public sector or not at all.

References

Aluminum Corporation of China (2012) 2012 college graduates recruitment notice. http://www.yingjiesheng.com/job-001-253-682.html. Accessed 22 Apr 2014

Bao S, Bodvarsson OB, Hou JW, Zhao Y (2011) The regulation of migration in a transition economy: China's hukou system. Contemp Econ Policy 29(4):564–579

Becker GS (1971) The economics of discrimination, 2nd edn. U of Chicago Press, Chicago

Beijing Municipal Transportation Committee, et al., 2013, “Implementing regulations of ‘Interim provisions regulation of Beijing small passenger automobiles numbers’ (2013 revision) (in Chinese),” issued on November 28, 2013, come into effect on January 1st,2014. http://www.bjhjyd.gov.cn/bszn/20131128/1385625116338_1.html (accessed June 22, 2015)

Bertrand M, Mullainathan S (2004) Are Emily and Greg more employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. Am Econ Rev 94(4):991–1013

Bodvarsson OB, Hou JW, Shen K (2014) Aging and migration in a transition economy: The case of China. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) Discussion Paper 8351

Borjas G (1987) Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. Am Econ Rev 77(4):531–553

Brencic V (2012) Wage posting: evidence from job ads. Can J Econ 45(4):1529–1559

Burdett K, Mortensen DT (1998) Wage differentials, employer size, and unemployment. Int Econ Rev 39(2):257–273

Chan KW (2012) Migration and development in China: trends, geography and current issues. Migr Dev 1(2):187–205

Chan KW (2013) China, internal migration. The encyclopedia of global human migration. Blackwell Publishing, Hoboken

Chan KW, Buckingham W (2008) Is China abolishing the hukou system? China Q 195:582–606

Delgado Helleseter M, Kuhn P, Shen K (2014) Employers’ age and gender preferences: Direct evidence from four job boards

Démurger S, Xu H (2013) Left-behind children and return decisions of rural migrants in China. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) Discussion Paper 7727

Depew B, Norlander P, Sorensen T (2013) Flight of the H-1B: Inter-firm mobility and return migration patterns for skilled guest workers. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) Discussion Paper 7456

Doeringer PB, Piore MJ (1971) Internal labor markets and manpower analysis. D.C. Heath and Co., Lexington; Mass

Du J, Wang Y (2013) Reforming SOEs under China's state capitalism. In: Zhang J (ed) Unfinished reforms in Chinese economy. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore, p 520

Dulleck U, Fooken J, He Y (2012) Public policy and individual labor market discrimination: An artefactual field experiment in China. Queensland University of Technology Business School Working Papers 002

Dustmann C (2000) Temporary migration and economic assimilation. Swed Econ Policy Rev 7(2):213–244

General Office of Xiamen People's Government (2013) Notice of the issue of the notice by Xiamen People's Government General Office on the opinions of the city to implement the 'State council on further improving the work of the real estate market regulation issues related notice'. http://www.xm.gov.cn/zwgk/flfg/sfbwj/201304/t20130402_622686.htm. Accessed 22 June 2015

He H, Huang F, Liu Z, Zhu D (2014) Breaking the iron rice bowl: Evidence of precautionary savings from Chinese state-owned enterprises reform. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2014–04

Hirsch B, Jahn EJ (2015) Is there monopsonistic discrimination against immigrants? Ind Labor Relat Rev 68(1):501–528

Hotchkiss JL, Quispe-Agnoli M (2009) Employer monopsony power in the labor market for undocumented workers. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper: 2009–14

House KE (2012) On Saudi Arabia: its people, past, religion, fault lines-- and future. Knopf, New York