Abstract

This paper provides a new perspective by classifying active labor market programs (ALMPs) depending on their objectives, relevance and cost-effectiveness during normal times, a crisis and recovery. We distinguish ALMPs providing incentives for retaining employment, incentives for creating employment, incentives for seeking and keeping a job, incentives for human capital enhancement and improved labor market matching. Reviewing evidence from the literature, we discuss especially indirect effects of various interventions and their cost-effectiveness. The paper concludes by providing a systematic overview of how, why, when and to what extent specific ALMPs are effective.

JEL classification: J08, J22, J23, J38, E24

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Heavily advocated by the OECD, ALMPs are of growing interest and relevance due to increasing unemployment also for transition and developing countries. Governments have been responding to the crisis through active labor market programs (ALMPs) like subsidizing employment and providing training and employment services. The job crisis may have increased unemployment persistence, leading to longer unemployment spells, an increase in long-term unemployment and subsequently to skill attrition–thereby, also having detrimental effects on future employment probability1. At the same time, tighter budget constraints highlight the relevance of evidence-based, cost-effective active labor market policy making to support recoveries. This paper aims to bridge the gap between understanding cost-effective ALMPs and boosting post-crisis recoveries. At the same time, as pointed out by Cazes et al. (2009) and as witnessed by take-up rates of ALMPs, for example, in work sharing arrangements2, time lags until policies can be operational need to be taken into account. Thus, this calls for an existing ready-to-implement policy strategy based on existing evidence, which can be adapted to the respective position in the business cycle.

This paper provides a new policy perspective in classifying ALMPs in light of their relevance and cost-effectiveness during normal times and recoveries to guide evidence-based policy making. We will discuss in particular the indirect effects, including macroeconomic and general equilibrium effects, as well as longer run effects determining the cost-effectiveness. We will also address the challenges for design and implementation in balancing these and avoiding disincentives. Instead of comprehensively reviewing existing programs and their evaluations across countries, the focus of this paper is rather to provide a systematic overview of the cost-effectiveness of ALMPs. In assessing the cost-effectiveness of ALMPs, we follow Heckman et al. (1999), asking whether ALMPs are effective for targeted workers in line with their respective aims and whether they are cost-efficient from a macroeconomic perspective3. In doing so, we provide a strong focus on indirect and macroeconomic effects.

We show that policies retaining employment like work sharing schemes can be applied in severe recessions for limited time periods. ALMPs creating employment perform much better in terms of cost-effectiveness and desirability by strengthening outsiders’ position in the labor market, especially during recoveries, and by raising the outflow out of unemployment, ultimately reducing labor market persistence. In-work benefits and public works are very cost-inefficient in terms of raising employment, but might be cost-efficient in reducing poverty and inequity. Policies readjusting distorted employment incentives, such as activation and sanction measures, have proven to provide cost-effective results, especially during normal times.

While short-run evaluations of ALMPs have not conveyed a consistent message on the cost-effectiveness, new longer-term evaluations clearly indicate cost-effectiveness from a longer-term perspective. This contrast is especially highlighted for training programs; evidence shows significantly positive long-run impacts. This is especially clear for on-the-job training and those targeted at disadvantaged outsiders. ALMPs improving labor market matching have an impact only in the short-run but are highly cost-effective.

Existing reviews and evaluations do not always take into account the full set of effects, including the longer-run effects which may only materialize many years after the program4. All these are, though, essential to determine the cost-efficiency of ALMPs and to understand why some programs work and others do not5.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: In Section 2, we present our new perspective on ALMPs. Section 3 provides an overview of indirect effects of ALMPs. Section 4 discusses the cost-effectiveness of the classified ALMPs based on evaluations of programs, and Section 5 concludes.

2 Categories of ALMPs

We present a new perspective on ALMPs by classifying them depending on their main objective. It is useful to distinguish five categories due to their distinct objectives as well as their different cost-effectiveness and relevance in a crisis, its recovery and “normal” times. Table 1 provides an overview of these five categories of ALMPs.

First, ALMPs that provide incentives for retaining existing employment consist of financial incentives to employers to continue their current employment relationship with workers and thereby aim to decrease outflow from employment. These measures are generally adopted for a limited period of time, support employed workers and are targeted at jobs at risk6. Most prominent measures are wage subsidies and reductions in non-wage labor costs as well as short work schedules or work sharing, which have been widely used in advanced economies during the crisis7. Short work schedules or work sharing programs are more complex subsidy programs; they incentivize employers to reduce labor costs along the intensive margin in contrast to the extensive margin while fully or partly reimbursing workers for hours not worked8. This category of ALMPs enables firms to keep workers and provide (at least temporary) job and income security to employees.

ALMPs providing incentives for creating new employment consist of incentives to private employers and workers to increase inflow into employment9. These measures thereby support labor market outsiders—that is, unemployed, inactive, and informal workers—and are often targeted at specific groups of unemployed workers such as long-term-unemployed and disadvantaged workers with outdated skills. Here, subsidies are also the most prominent measures, specifically wage and hiring subsidies directed at private employers, reducing their labor costs (e.g., salary or social contribution costs) and, thus, providing incentives to employ new workers10. But also self-employment or entrepreneurship incentives which provide financial incentives and advisory services to unemployed workers fall under this category. These ALMPs can be targeted at specific groups and usually involve some screening of feasible business plans11.

In contrast to the previous two groups, the next group of ALMPs providing incentives for seeking and keeping a job primarily address labor supply by increasing the payoff from employment for workers12. These instruments provide incentives to work to low-wage, unemployed, discouraged, and inactive workers but at the same time also have an explicit and clear redistributive objective. Important instruments are again financial transfers and subsidies, but these are specifically paid to the workers as an income supplement in the form of, for example, in-work benefits13. Also public works, which might seem partly misplaced in this category, pursue an explicit social safety net goal due to their history of ineffectiveness in achieving intended effects. Specifically, public works are increasingly being applied as workfare–the obligation to produce publicly useful goods or services as a condition for the receipt of unemployment benefits or social assistance. Thus, as activation instruments, they aim, together with the often associated sanctions, to reduce the disincentives to search for jobs and work created by passive labor market policies.

To raise the employability and productivity of workers, some ALMPs provide incentives for human capital enhancement by upgrading workers’ skills. These fourth category measures are widely used in Europe and either directly provide or finance14 labor market training and retraining in classrooms covering basic job skills or specific vocational skills as well as on-the job training15. These measures are targeted at unemployed and employed workers at the same time taking into account labor demand requirements.

Improved labor market matching policies aim at raising the probability, efficiency and quality of labor market matching by supporting job seekers and employers as well as by taking an intermediate and brokerage role to overcome informational deficiencies16. Among the wide range of instruments, the main elements are job search assistance and employer intermediation services; the former helps unemployed workers find a job through counseling and support services, access to and provision of information on the labor market situation and trends17. The latter identify employers’ needs and establish contacts with potential employers. These services are offered either traditionally by public employment services or by private agencies, which prefer higher-skilled workers18. Often the participation in these measures is also a condition to continue qualifying for unemployment benefits or combined with sanctions, thereby part of the rights and obligations package19.

3 Effects of ALMPs

To assess in line with their respective objectives whether ALMPs benefit the targeted workers as well as whether they are cost-effective and socially desirable from a macroeconomic viewpoint, it is crucial not only to evaluate the direct effects on employment, unemployment and earnings. Also partly countervailing indirect and general equilibrium effects on wage bargaining, incentives of targeted and third party employers and workers etc. need to be explicitly evaluated, since they contribute to a net employment effect. Along the same line, implications for the government budget and the effects on the composition of and dynamics between labor market states need to be taken into account20. Furthermore, beyond mere impact effects, long-run effects of these policies must be taken into account. Reviews by Martin and Grubb (2001), Calmfors et al. (2001) and Kluve and Schmidt (2002) cleary show the lacking evidence on the relationship between ALMPs and job durations.

According to Calmfors (1994), the direct effects on employment, unemployment and earnings act via three mechanisms: (i) an improved matching process; (ii) increased and enhanced labor supply; and (iii) increased labor demand. Since these are well understood, we will focus on describing the indirect effects21.

The indirect deadweight effect lowers the cost-effectiveness of ALMPs. It refers to the resources of the policy that go to beneficiaries who would have achieved the objective of the policy even in its absence. For example, it reflects the amount of hiring subsidies that are paid for hiring workers who would be hired even without the subsidy. While not completely avoidable, it can be minimized by concrete targeting of workers, for example those with the lowest exit rates out of unemployment.

The effectiveness of ALMPs can be further undermined by the cream-skimming effect, by which only workers with high employment probabilities are selected into the program22. This is especially significant if caseworkers assign workers to ALMPs and need to deliver a good reemployment rate of participants23.

The displacement effect in the labor market captures the fact that employment generated by ALMP might displace or crowd our regular employment, which lowers the effectiveness of the instrument24. For example, firms hire subsidized workers instead of hiring unsubsidized workers, or unsubsidized employed workers are fired and replaced by subsidized workers. In addition, the displacement effect also covers the fact that once the subsidy expires, the formerly subsidized worker is fired. Brown et al. (2011) illustrate that this effect can be reduced through effective targeting or tolerated if this enables long-term unemployed workers to reenter employment, regain work-routine and skills on the job, improving their longer-run employability. Often only additional jobs are subsidized, which reduces take-up rates, in order to significantly reduce displacement effects25. Furthermore, Martin and Grubb (2001) argue that in the medium run, capital will adjust and, thereby, the displacement effect is only relevant in the short run.

Another unintended effect of ALMPs is the substitution effect, by which incentives to employers are generated to substitute one skill-class of workers for another one to do the same jobs due to a change in the respective relative labor-costs. For example, low-wage subsidies might create the incentive for firms to substitute medium-ability workers with low ability workers. In contrast to the other mentioned effects, this effect lacks empirical support in the literature, which suggests that substitutability between different skill groups is small26.

The wage-effect reduces the effectiveness of policies and is defined as the resources of the ALMP that go into wage increases and thereby do not create new employment. For example, a subsidy reduces the firm’s labor costs, which increases the bargaining surplus, of which the worker will capture her share27.

During ALMPs workers may have less time or be less inclined to search for a job. The so-called locking-in effect (also called retention effect) refers to the lower probability of finding a job of ALMP participants compared to the unemployed who are not in ALMPs28. Calmfors (1994) expands the locking-in effect by also including the negative effect on search behavior due to the prospect of participating in an ALMP, for example, due to its attractiveness, its pay, or its lack of required geographical mobility. Martin and Grubb (2001) point out that the locking-in effect is particularly strong if participation is voluntary or if it is necessary to participate to qualify for continued receipt of unemployment benefits. This effect can be weakened by compulsory participation without additional pay on top of benefits or at a minimum wage, since workers might be able to earn more in regular employment. The authors argue, though, that monitoring of the job seeking behavior and job search assistance during participation and avoiding targeting workers who recently became unemployed and thereby still have high employment probabilities can limit the locking-in effect.

ALMPs may have negative effects on participants’ future employment probabilities due to the participation in the program; if the measure is too tightly targeted at very disadvantaged workers, they may be stigmatized. The stigmatizing effect signals low productivity to employers and prevents them from hiring workers participating in ALMPs29. Early evidence from Burtless (1985) on too tightly targeted wage subsidies in the USA shows that due to stigmatization, ALMPs can have the contrary effect of reducing reemployment probabilities.

Skill-acquisition incentives might be negatively affected by ALMPs, the consequences of which only materialize in the medium-run. For example, the negative skill-acquisition effect can be illustrated by low-wage subsidies, which might create disincentives for unskilled workers to gain further human capital, since the subsidy reduces the wage differential between unskilled and skilled work31. Oskamp and Snower (2006) show that positive short-run employment effects can be outweighed by the longer-run consequences of this effect.

Subsidies targeted at unskilled workers may provide an incentive to switch from full to a part-time employment in order to cash in the subsidy, but limiting the subsidy to full-time positions potentially provides incentives for firms and workers to collude and cheat the government to qualify for the subsidy due to asymmetric information 32.

While the negative indirect effects can be substantial, ALMPs can also have positive indirect effects:

The so-called competition effects highlight ALMPs’ role in strengthening outsiders’ position in the job market relative to insiders. According to the insider-outsider theory, labor turnover costs, firing costs as well as hiring and training costs for new employees give insiders market power, which they use to their own advantage, for example, to push up their own wages33. The competition effect strengthens outsiders’ position and, thus, exerts a downward pressure on wages in addition to a labor supply effect, thus, raising employment34.

The prospect of participating in ALMPs might (in contrast to the locking-in effect) generate an ex-ante threat effect, which characterizes the increased incentives for unemployed workers to search for a job. This is the case for activation policies where the payment of unemployment benefits is conditional on the participation in workfare programs35.

Bringing unemployed workers back into work via ALMPs will increase their employment probabilities by the transition effect. This effect is strongest for long-term unemployed workers, who during their unemployment suffer from skill attrition and loss of work routine36. If, for example, subsidies enable these long-term unemployed workers to transition back into employment, workers gather work habits and routines, and their human capital appreciates37. Once the subsidy expires, they are more valuable to the employer than originally, their retention rate is higher than their former hiring rate. Even if they are fired at this point, the former long-term unemployed workers are now short-term unemployed with an increased human capital and higher reemployment probabilities than long-term unemployed workers38. As Heckman et al. (2002) point out, bringing workers into employment can have longer run impacts on workers’ human capital and employment path.

Similarly the screening effect or signaling effect of ALMPs enables employers to collect information on the productivity of workers. Due to informational asymmetries on workers’ productivity, long-term unemployment, for instance, may signal low productivity to firms. ALMPs can indirectly improve the matching on the labor market by enabling firms to experience workers’ productivity, e.g., via subsidized employment39.

Last but not least, budget effects have to be taken into account when evaluating the cost-effectiveness in line with policy makers’ concerns. Also here this involves indirect effects. On the one hand, ALMPs financed by increasing taxes decrease the payoff from employment and, thereby, provide disincentives to work and search effort for all workers40.

On the other hand, these measures might generate additional tax revenue by bringing people into employment and generate savings in unemployment benefits and social assistance, which can be used to finance these measures41.

The design of ALMPs is crucial for their effectiveness. Focused targeting of measures can reduce negative indirect effects and give rise to positive ones, but it has to avoid stigmatizing workers and creating cost-intensive monitoring or bureaucraticc procedures, thereby reducing employer take-up. US evidence from Burtless (1985) and Katz (1998) shows that employer reporting requirements increase administrative costs and significantly reduce take-up.

Calmfors (1994) also discusses at which point in the unemployment spell workers should be targeted, since a later targeting reduces deadweight and locking-in effects, while at the same time this implies stronger skill attrition and more discouragement on part of the workers due to longer unemployment duration.

For a holistic approach, ALMPs must take into account the interactions, complementarities, and repercussions with other active and passive labor market policies42. Betcherman et al. (2004), Martin (2014) and Kuddo (2009) recommend a combination of sticks and carrots to provide incentives to search for and accept jobs, to provide employment incentives by making participation mandatory with the threat of benefit sanctions, and point to evidence of higher effectiveness. In contrast, many other studies, e.g., Calmfors et al. (2001), Martin and Grubb (2001), Kluve and Schmidt (2002), Kluve et al. (1999), Kluve et al. (2008) and Sianesi (2001, 2004), provide robust evidence that participation should not be used as an incentive instrument to (re-) qualify for the receipt of unemployment benefits since this would lead to costly churning effects and boost program sizes43. The churning effect refers to the providing of incentives to workers who have little interest in regular employment and only participate in ALMPs in order to gain entitlements for another round of unemployment benefits.

In the following, we will discuss the relevant effects for each category of ALMPs, review evaluations of these policies to determine their effectiveness and assess their suitability as an instrument during an economic crisis, the recovery from it as well as during the normal business cycle.

4 Effectiveness, evaluation and suitability of various ALMPs44

4.1 Incentives for retaining employment (Category I)

ALMPs providing incentives for retaining employment via subsidies to employers or work sharing schemes that aim to support or increase labor demand and, thereby, prevent an increase in unemployment due to a fall of economic activity. The OECD (2010) argues that these measures aim at preventing inefficient separations of workers who would have been retained in the longer-run in the absence of a temporary reduction in demand. Furthermore, the authors attribute to these measures the potential not only to raise efficiency but also equity by more equally distributing the cost of the crisis among the workforce45. Nonetheless, deadweight and substitution effects might be very substantial for these measures since they target all employed workers of a specific skill, industry or area. Calmfors (1994), Marx (2001) and Martin and Grubb (2001) review evaluations for the OECD and summarize that deadweight and substitution effects undo between 42 to 93 percent of the direct employment effect of wage subsidies, with general subsidies at the higher end46. Studies on Sweden put the value of deadweight, on average, at 60%47, and more recent evidence from Betcherman et al. (2010) reveals between 27% and 78% of deadweight depening on the design. Neumark (2013) surveys the evidence from the US and finds deadweight costs between 67% and 96%, and recent evidence for Germany by Boockmann et al. (2012) shows that deadweight costs fully absorb positive employment effects. Another recent study by Betcherman et al. (2010) clearly shows the importance of targeting in this respect: Turkish wage subsidies were subject to deadweight costs of 27% or 78% depending on design. Marx (2001) reviews various studies also generating substitution and displacement costs between 20% and 50%.

In addition, these instruments provide incentives to collude and cash in on the government subsidy, for example, taking up subsidized working hour reductions when this would be unnecessary to prevent separations.

Wage effects might also significantly weaken wage subsidies’ effectiveness, since they are exclusively targeted at insiders, who will bargain for a share of the subsidy, whereby the effectiveness of this policy is weakened. Temporary workers are often discriminated in work sharing schemes, which also strengthens the position of insiders vis-à-vis outsiders and thereby increases labor market segmentation48. Furthermore, these measures make it more difficult for outsiders to enter employment, which reflects a negative competition effect in the labor market as well as displacement of regular new employment since jobs can be preserved which would not have been conserved without the program, even after the economic situation recovers.

Thereby, by locking workers in low-productivity jobs and reducing the outflow from employment, these measures also reduce the outflow from unemployment as well as outsiders’ employment prospects49. Ultimately, these measures will increase the persistence in the labor market. If these policies are not implemented only for a very limited period, they will have longer lasting negative effects, that is, increasing structural and long-term unemployment, and the resulting skill attrition of unemployed workers as well as workers dropping out of the labor force. An additional longer-term side effect of the subsidies and also the work sharing schemes—if not combined with training measures in the hours not worked—is an increase in unemployment-prone labor market groups due to the disincentives for skill acquisition.

Besides the lowest skilled and productive workers, which are the most likely to be laid off in a recession, will be those entering the work sharing schemes50, thereby lowering aggregate productivity. A longer use of these instruments may keep non-competitive jobs and inhibits efficient labor reallocation51.

Both wage subsidies, in particular, and work sharing schemes imply a significant cost to the government52. For example, Huttunen et al. (2013) analyzed low-wage subsidies in Finnland which yielded huge fiscal costs but little employment effects and, thus, had been discontinued. On the other hand, the three countries making most extensive use of work sharing programs, Germany, Italy and Japan, in 2009 spent between 0.1% and 0.3% of GDP53. Again design is crucial to balance cost-effectiveness and take-up54.

Work sharing schemes have played a prominent role in OECD countries’ policy reaction to the economic crisis—they have been adopted in over three quarter of the OECD countries55 and involve up to 5 percent of the workforce. Some countries, for example Germany’s Kurzarbeit and France’s chômage partiel, already had programs in place and have extended them and eased design features to simulate take-up, while others have set up new programs56. While, on average, these schemes played an important role in retaining employment, take-up rates and effectiveness have varied significantly between countries, which has been attributed to design features and whether schemes were already in place57.

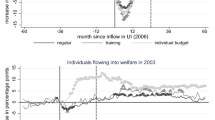

The work of the OECD (2010) and Boeri and Bruecker (2011) as well as empirical research reviewed by Cahuc and Carcillo (2011) suggest that work sharing schemes in the OECD significantly reduced the rise in unemployment, but they also confirm substantial deadweight costs (schemes are used to subsidize working hour reductions that would have been adopted also in the absence of the scheme) and suggest similar displacement costs58. Furthermore, Hijzen and Venn (2011) support that in contrast to permanent jobs, temporary jobs have not been saved through work sharing arrangements, which strengthens market segmentation and insiders’ position. The OECD (2010) also shows that countries with already existing programs have been more effective in retaining employment than countries which have set up a new scheme and attribute also the low take up rate in the latter countries to the time-lag involved in introducing and implementing a new scheme in the wake of a crisis. Several countries combined the work sharing scheme with partly subsidized training measures in the hours not worked, which, if not obligatory, was taken up only by up to 25 percent of the workers involved in the schemes59.

The intensively used German “Kurzarbeit” scheme and its success in keeping unemployment down have been widely praised and generated interest in the relevance of these programs as a tool to combat economic crises. According to the OECD (2010) and Boeri and Bruecker (2011), the German scheme has saved approximately. 400,000 jobs by the third quarter of 200960, and Brenke et al. (2011) point out that unemployment would have doubled its rate since mid-2009 in the absence of the scheme. Boeri and Bruecker (2011) highlight only moderate deadweight costs of this scheme, which the OECD (2010) estimates to be a third of the cost, and suggest this to be a result of its optimized design features (eligibility and entitlement conditions)61.

Brenke et al. (2011) and the OECD (2010) point out the importance of such schemes in fitting into the institutional framework and with other labor market policies (for example, centralization of wage bargaining). Worker and employers in countries running a flexicurity set of labor market policies, for example, involving low firing costs and high unemployment benefit replacement rates will have low incentives to take up a work sharing scheme unless it is heavily financed by the public budget.

Boysen-Hogrefe and Groll (2010) show that the so-called German Job Miracle and the intensive use of adjusting hours can only to a minor extent be attributed to the German Kurzarbeit, which is quantified by Fuchs et al. (2010) to a third of working-time reductions62.

Boeri and Bruecker’s (2011) results stress that work sharing schemes are only effective in steep downturns, and also the OECD (2010) attributes a higher effectiveness to an existing scheme at the onset of the recession. Furthermore, the negative effects of this measure will be smaller in a deep recession, but can rise dramatically in a recovery63.

Thus, both authors suggest, that it may be useful, if policy complementarities are taken into account, to have a small scheme with discouraging eligibility conditions and generosity to minimize above mentioned negative effects running in normal times. Such a scheme could then be swiftly scaled up by adapting the requirements and benefits to retain workers in employment in the short-run once temporary severely negative economic circumstances impact64. To limit negative effects in the presence of closely binding budget constraints, after a very limited period of time, the scheme should be tightened back again irrespectively if a recovery takes hold or not65. The OECD (2010) though points out the lack of empirical evidence to support such a policy stance.

In conclusion, while for the reasons stated above, wage subsidies have proven very cost-ineffective and undesirable to incentivize the retention of workers. Work sharing arrangements, if applied for a very limited period of time at the onset of a severe economic crisis, may alleviate the impact of the crisis on employment. This measure enables employers to reduce labor costs and at the same time retain skilled and trained workers and keeps insiders in employment with full or partial conservation of their income. Importantly, these schemes should be combined with training during the hours not worked to support skills development and combined with measures to significantly support outsiders. Nonetheless, the longer-run implications also have to be taken into account, i.e., the risk of increasing labor market persistence and long-term unemployment by disadvantaging outsiders as well as delaying inevitable labor reallocation, which might also obstruct recovery.

4.2 Incentives for creating employment (Category II)

ALMPs providing incentives for creating employment involve mainly financial incentives, that is, subsidies for employers and also entrepreneurship advisory services to encourage employment in the private sector. The scale and applicability of subsidies on the one hand and entrepreneurship support on the other hand are different; therefore, we will discuss their effects and evaluations separately.

A wide range of differently targeted and designed wage and hiring subsidies exist which can increase job matching by incentivizing job search and raise labor demand by subsidizing employer’s labor costs66.

Betcherman et al. (2004) point out that most evaluations of subsidies do not show positive impacts on post program employment or earnings. As pointed out in the previous section, wage subsidies entail huge indirect effects, especially deadweight, substitution and displacement, making them cost-ineffective and undesirable due to their long-run implications on skills development67.

To reduce indirect effects via appropriate targeting, the focus should be on hiring unemployed workers via hiring subsidies, which are more cost-effective68. These measures, thereby, support labor market outsiders—that is, unemployed, inactive, and informal workers—and are often targeted at specific subgroups such as long-term-unemployed workers with outdated skills. In contrast to wage subsidies, which are targeted at specific groups of workers irrespectively of whether they are new hires or already employed, hiring subsidies exclusively redistribute incentives to unemployed workers.

Various reviews of studies around the world (Heckman et al. 1999, Card et al. 2010) focused on OECD countries (Martin and Grubb 2001), and especially evaluations for Sweden (Sianesi, 2008; Carling and Richardson, 2004), highlight that private sector hiring subsidies can generally be more effective in benefiting the targeted workers by bringing them into employment than public education and training measures or public works69. For example, evidence on the success of hiring subsidies in Austria is presented by Dauth et al. (2010), for Australia by Stromback and Dockery (2000), for Poland by O’Leary et al. (1998), for Slovakia by van Ours (2000), for Gemany by Jirjahn et al. (2009) and Bernhard et al. (2008a), for Sweden by Sianesi (2004), Carling and Richardson (2004), and Forslund et al. (2011) as well as for the New Deal for young people in the UK by Bonjour et al. (2001) and Dorsett (2006). However, design features always strongly affect the impact and success of hiring subsidies.

Evidence for various countries shows that hiring subsidies outperform other ALMPs in terms of post program employability70. A survey by Neumark (2013) of US evidence highlights that, using unfavorable estimates, hiring subsidies are at least more than twice as effective as public job creation. Bernhard et al. (2008b) analyzed participation in hiring subsidies for welfare recipients in Germany and provide evidence that approximately 70 percent of participants gained regular employment, the effect of hiring subsidies amounted to around 40 percentage points.

Thus, evidence shows that hiring subsidies bring workers into employment, and these workers are retained, but often these evaluations do not look at longer run effects and do not take indirect effects into account71. In general, such indirect costs tend to be much smaller for hiring subsidies.

First, hiring subsidies are paid for a limited period. For this reason, in contrast to wage subsidies which can prove difficult to phase out72 and are subject to strong locking-in effects, subsidizing hirings have lower locking-in effects73. The limited duration feature of this instrument also reduces potential substitution effects and disincentives to acquire human capital in contrast to wage subsidies. As pointed out above, in contrast to the other mentioned indirect effects, the former effect lacks empirical support in the literature74.

Second, they cover new hires, thus outsiders, who in contrast to insiders are less protected by labor turnover costs and thereby, have a weaker bargaining position75. This is confirmed by Stephan’s (2010) microeconomic evidence for Germany showing that wages of new workers are not affected by hiring subsidies76. At the same time, by redistributing employment incentives to the disadvantaged outsiders, hiring subsidies increase the competition in the labor market, put downward pressure on wages and, thereby, indirectly increase employment77.

Third, they generally target disadvantaged workers, e.g., long-term unemployed workers, which have low probabilities of becoming employed, and furthermore, significantly less workers are covered by hiring subsidies, e.g., for the long-term unemployed relative to low-skill wage subsidies.

Thereby, the resulting deadweight costs can be expected to be smaller – evidence for Germany by Bernhard et al. (2008b) places it at 20-30%. But again, design is crucial; evidence for hiring subsidies for older workers by Boockmann et al. (2012) reveals that deadweight costs absorb any employment effects. Deadweight costs can be further minimized by tightly targeting workers with the lowest exit rates out of unemployment, but not completely avoided.

Nonetheless, hiring subsidies might still entail significant displacement costs, capturing the fact that employment generated by ALMP might displace or crowd our regular employment; for recent US evidence, see Neumark and Grijalva (2013). Hiring subsidies may incentivize firms to hire subsidized workers instead of unsubsidized workers, to lay off workers in order to hire subsidized workers or to lay off subsidized workers once the hiring subsidy expires. This indirect effect also significantly lowers the cost-effectiveness of programs since it clearly influences the net employment effect. Swedish studies find sizeable displacement effects for Swedish hiring subsidies of around 65-70%, and studies for Ireland and the UK 20%, for Belgium 36% and for the Netherlands 50%78.

In order to enhance their cost-effectiveness, hiring subsidies can be targeted at disadvantaged workers, for example long-term unemployed workers. As highlighted by Martin and Grubb (2001) and Neumark (2013), tight targeting can raise net employment impact by 20–30 percent, but it needs to balance still being attractive for employers to take up as well to avoiding stigmatization. A study by Fay (1996) on a smallscale British project for long-term unemployed people concluded that the deadweight loss amounted to no more than between 15 and 20 percent79. Employers may be asked to reimburse a share of the subsidy if the worker is dismissed within a certain period, which would also decrease churning and increase transition effects80. Documentation and reporting requirements may however create cost-intensive monitoring or bureaucratic procedures, thereby reducing employer take-up81. Recent evidence by Moczal (2013) on German wage subsidies for hard to place welfare recipients confirms low deadweight costs but also low take-up of tight targeting. Stigmatization results from too tight targeting of very disadvantaged workers, since workers participating in the program may then be perceived as signaling low productivity. Thus, too tight targeting can result in employers refraining from hiring workers, stigmatizing workers and effectively reducing their future employment. Evidence for this effect has also been widely documented82.

Displacement effects though may not be that significant. Apart from reducing them through sensible targeting, displacement could also be tolerated if the transition effect and also the screening effect are sufficiently large:83

The former refers to the fact that subsidized hirings enables employers to gain information on the productivity of workers. Among others, the review by Betcherman et al. (2004) and especially evaluations from Sweden and Switzerland (Gerfin and Lechner 2002, Kluve et al. 2008 as well as Sianesi 2008, 2001), point to evidence of effective programs in which employers effectively use subsidized hirings as screening devices as substitutes to work experience. Based on the gained information on the productivity of workers, employers may be more willing to retain the worker after the program than they would have been willing to hire her without the subsidy84.

By bringing unemployed workers into a job, hiring subsidies enable workers to sustain or regain their skills and thereby enhance effective labor supply85. Their previous low employment probability is exchanged with a higher retention probability, and even if laid off once the subsidy elapses, workers have higher reemployment probabilities than previously86. This effect is also highlighted in recent German evidence from Neubäumer (2012) revealing the same employment rate after several years for workers who got hired into a subsidized job as well as workers who received formal work-specific training and became immediately employed. This implies that employers value on the job learning via a subsidized job as much as formal training programs. Also evidence from Sweden and Switerland (Carling and Richardson, 2004 and Gerfin and Lechner, 2002) shows that work-specific human capital seems to be clearly valued by firms. The broad evidence that the closer subsidized employment is to regular employment the more valuable it is also supports this notion87.

The transition effect will be strongest for long-term unemployed workers who suffer from skill attrition and loss of work routine. Swiss evidence by Gerfin et al. (2005) highlights the stronger effects for the long-term unemployed. Recent evidence from Sjögren and Vikström (2013) on hiring subsidies targeted at long-term unemployed workers in Sweden reveals that the subsidy duration positively affects the retention probability. In contrast to increasing the subsidy rate, increasing durations is irrelevant for job finding rates, which may indicate, as one can expect, that transition effects need longer to materialize than screening effects. Further evidence from Slovakia, the UK's New Deal, from the US's Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and recent evaluations of different German labor market programs is presented by Jirjahn et al. (2009) and Bernhard et al. (2008a and b) on a significant transition effect88.

Hiring subsidies’ cost effectiveness depends on whether they impact workers’ employment prospects in the longer-run mainly via these effects. To capture the full longer-run implications of these effects, it is crucial to evaluate their impact on the longer-run development of employment careers89. Only recently did empirical research start looking at longer term effects, e.g., at the relationship between ALMP and job durations90. Longer-term evaluations provide evidence that short-term rankings of instruments’ effectiveness can be overturned and, thereby, highlight the need of longer-run evaluations and that hiring subsidies can indeed be cost-effective. For example, German evidence shows that 20 months after taking up a subsidized job, the probability of being in regular employment is around 40 percentage points higher. The evidence by Sianesi (2008) for Sweden reveals that hiring subsidies performed best in cost-effectiveness and led to higher employment probability of 40 percentage points after the program and 10 percentage points after 5 years, averaging to 19 percentage points over 5 years. Also Calmfors et al. (2001) find that hiring subsidies have a positive impact on future employability. As discussed, these effects will be stronger for long-term unemployed workers and should be targeted, as suggested by the evidence of Bernhard et al. (2008b) and Gerfin et al. (2005).

Hiring subsidies appear cheapest among the Swedish active labor market measures, and especially those targeting long-term unemployed workers perform best and have been the cheapest instrument91. Van Ours (2000) reports that hiring subsidies in Slovakia seem the most efficient active labor market policy. While these studies do only relate to direct budget effects, Brown et al. (2011) confirm the cost-effectiveness of hiring subsidies in their simulations. The authors show that by bringing long-term workers back into employment, these hiring subsidies could be self-financing via saved unemployment benefits payments and additionally generated tax revenue.

In sum, as Martin and Grubb (2001) point out, limited period hiring subsidies to private employers can indeed be cost-effective and have sizeable macroeconomic employment effects, but they have to balance negative effects, which calls for sensible targeting of hiring subsidies.

To maximize competition, transition and screening effects, hiring subsidies should be targeted at the losers in the labor market, for example, the long-term unemployed workers and inactive workers92, and to increase cost-effectiveness, subsidy payments should continuously increase with unemployment duration93.

Even if the positive employment effects on the one side and significant deadweight and displacement effects on the other side outweigh each other, implying no increase of total employment, hiring subsidies may still be desirable94. By redistributing employment incentives to the disadvantaged, strengthening their attachment to the labor market, and thereby reducing long-term unemployment, they increase labor market flows and reduce labor market persistence and enable a more equitable distribution of unemployment95. Thereby, hiring subsidies can be a significant countercyclical labor market stabilizer in normal times to avoid increases of long-term unemployment and detachments from the labor market96.

These instruments can perform as countercyclical labor market stabilizers in normal times to avoid increases of long-term unemployment and detachments from the labor market. Furthermore, As shown by the OECD (2010), various OECD countries in response to the crisis have adopted hiring subsidies targeted at disadvantaged parts of the workforce as well as reductions of non-wage labor costs for hires. While these instruments might be cost-ineffective once an economic crisis hits, they are an important device once the recovery is in sight to support it and incentivize the recruitment of disadvantaged workers97.

Nonetheless, in recessions, the equity aspect might be of relevance to avoid disadvantaged workers leaving the labor market and to give them a competitive edge in the search for jobs. Targeting should be tightened once the recovery accelerates to reduce costly negative indirect effects98.

This category also encompasses a generally smaller program in size and applicability of providing incentives for self-employment. Besides the direct objective of supporting the outflow of unemployment into self-employment, the indirect desired implication of these programs is that the start-ups create further employment.

While the thin and only microeconometric evidence on such programs is mixed, positive or insignificant, recent evidence signals more positive impacts. Reviews by Betcherman et al. (2004), Cazes et al. (2009), Kuddo (2009) and Martin and Grubb (2001) partly indicate positive effects on employment probability after the program for male, better educated workers of 30–40 years with particular interest in entrepreneurial activities, but mixed evidence on future earnings99. Almeida and Galasso (2007) find significant income effects in Argentina only for young and highly educated individuals. Rodriguez-Planas (2010), evaluating a Romanian program, shows strong employment effects for low-skilled workers100. Carling and Gustafson (1999) present evidence of self-employment grants being more effective than hiring subsidies in Sweden. Advisory services on their own or combined with financial incentives generally generate better results than only financial incentives101.

Most of the authors point out the usefulness of the instrument, but its restricted applicability to a small fraction of the unemployed workforce of up to 3 percent. The studies though usually only evaluate the short-term effects of the program, while as pointed out previously, it is important to analyze the long-run effects over workers’ employment history.

Indirect effects of these instruments have typically not been evaluated102.

Deadweight effects as well as displacement costs are though likely to be high for this instrument as well. At the same time, increases in the employability of participants through transition and indirectly screening effects are also potentially large. Workers will acquire human capital relevant networks, and their initiative to start up their own business is a signal to future employers, whereby if they leave self-employment, their employment probability will be higher than before. Similarly, competition effects will be strong.

A recent evaluation of two German self-employment subsidies for the unemployed from Caliendo and Künn (2010) provides new interesting results in this respect103. In their partial equilibrium analysis, the authors evaluate the longer-run impacts 5 years after self-employment. Their results show significantly higher income after 5 years and a 20 percent higher employment probability for participants. Furthermore, in contrast to the studies above, self-employment subsidies are especially effective for the disadvantaged workers in the labor market. The authors explain this finding with the low employment prospects for the disadvantaged groups, providing them with incentives for self-employment then has a strong effect (relative to non-participation).

These results strengthen the suitability and desirability of ALMPs providing self-employment incentives to redistribute incentives to the disadvantaged to move from unemployment into self-employment and strengthen their labor market attachment, to promote adaptability to new labor market conditions as well as to support recoveries.

Summing up, in contrast to ALMPs aiming at generating incentives for employment retention, these aiming at employment creation, due to their strong transition, screening and competition effects, have generally proven to be more cost-effective and suitable to provide labor market losers with incentives to adapt and work, especially in recoveries. This targeting, which is desirable from a social perspective, also limits cost-ineffective deadweight effects.

4.3 Incentives for seeking and keeping a job (Category III)

This category groups measures raising labor supply by directly increasing the return from employment or by making unemployment more costly. Measures such as making work pay schemes and public works though do not have the sole objective of increasing employment but rather often prioritized the aim of redistributing income104. The ultimate employment objective is to mitigate the disincentives to search and work created by passive labor market policies.

The first set of measures in this category comprises financial transfers in the form wage subsidies to workers, for example in-work benefits, reductions in social security contributions, tax credits and other making work pay schemes paid to low-wage workers or low-income families to raise their income conditional on working. These measures have been especially pioneered and increasing in size in countries like the USA (Earned Income Tax Credit - EITC) and the UK (Working Families Tax Credit - WFTC) and are given credit for positive labor market developments. They have recently entered the debate as acceptable reform instruments compared to tax or benefit reductions, especially in Continental European Countries, where high tax and social contribution rates as well as generous unemployment benefits and social assistance create strong disincentives to work105.

In contrast to passive labor market policies, these measures are conditional on employment and generate incentives for specific disadvantaged labor market actors to increase work at the intensive or extensive margin. The direct effect employment of these measures clearly lies in raising labor supply and labor force participation, increasing transition into employment and activating discouraged workers who have left the labor force by generating employment incentives and thereby, improving income and future employment prospects106.

In addition to being cost-ineffective, low-wage subsidies are detrimental to long-run skills development107. Specifically, the skill-acquisition and locking-in effects are especially pronounced with these kind of measures. These financial transfers, especially if they are permanent, may create disincentives for unskilled workers to move to a better job and/or enhance their human capital108. Any resulting payoff in wages from better jobs or training is lower since workers will lose entitlement to (part of) the financial transfers109. Thus, these measures effectively decrease wage differentials between low-wage work and high-skilled work. Not only will this effect increase the relative number of unskilled workers, who are associated with higher unemployment rates, but it will have significant longer-run effects.

Immervoll and Pearson (2009) highlight that the negative skill-acquisition effect is also likely to outweigh any positive transition effect, by which the transition into employment counteracts skill attrition and loss of work routine implications of unemployment. The reason is that while the former effect is significant, the latter, especially in the lowest-productivity jobs, might be more limited.

Further disincentives might arise, for example, to reduce working hours or shift from a full-time to a part-time position in order to receive the transfer110. In this context the asymmetric information effect could strengthen the influence of these disincentives, namely, if employers and workers collude to cash in on the transfer, for example, by falsely claiming lower hourly wages and more working hours111.

As the same instruments targeting the demand side, these are also not cost-effective in terms of the employment objective – from a poverty alleviation perspective they may be desirable. But also for the latter, these instruments entail a trade-off between coverage and costs, especially in countries with compressed wage distributions, as shown for Belgium by Marx et al. (2011).

Immervoll and Pearson (2009) point at the countervailing impacts in terms of wage effects, reinforced by the competition effect112, on the two objectives. Employers will capture a share of the transfer implying lower wages113. The larger the share is, the weaker will be the negative effect on employment in the low-skilled sector, but at the same time, the lower will be the reduction in working poverty.

Analyzing the US Unemployment insurance bonus experiments, Davidson and Woodbury (1993) estimate that displacement and substitution effects amount to 30–60 percent of the direct employment effect in the target group. A different supply-side displacement aspect has been raised by Lise et al. (2006) for the Canadian Self-Sufficiency Project (SSP). Specifically, only workers receiving income assistance (paid once unemployment insurance benefits are exhausted) are entitled to the transfer. This created implicit disincentives for low-skilled workers not yet covered by income assistance to look for a job114. The reduced reemployment probability counters the increased job-finding rate for those in income assistance, thereby cancelling out any employment effect.

As before, effective targeting and design are essential for cost-effectiveness, and various approaches can be found, for example, permanent or transitional transfers for all or only newly employed low-wage earners or low-income families115. The dual objectives make this issue even more complex as the controversy on individual or family-based targeting reflects116. While low-wage subsidies are generally individualized schemes conditioned on individual incomes (like the Canadian SSP or the Belgian Work Bonus), tax credits (like the EITC or WFTC) depend on family size and are means-tested on household income.

Family-based tax credits can be effectively targeted at poor working families. They are particularly effective in achieving both goals, labor market participation and poverty alleviation, for single workers (according to Brewer et al., 2006, the WFTC increased labor supply of single mothers by around 5.1 percentage points). Nonetheless, at the same time, they provide disincentives for married women with working partners117, since earnings by second earners might lead to a loss of entitlement.

In contrast, on the one hand, low-wage subsidies as an example for individualized measures not only cover a wider number of workers, thereby, generally – assuming the same government expenditures – with a lower transfer, they are also less effective in targeting the poor118. Low-wage workers receiving transfers may not necessarily be at the bottom of the household income distribution119. On the other hand, while having smaller effects, low-wage subsidies do not create disincentives to second earners, but rather improve the employment incentives of both married and single women120.

In the US and UK experiences, the success of tax credit measures is reflected by the fact that the effect on single mothers outweighs that on second earner couples121. In contrast, Bargain and Orsini (2006a), who simulated labor supply effects for European countries, show that the overall participation effect for women is negative for an introduction of the WFTC. The authors argue that the differences in the results are due to a wider wage dispersion and lower levels of taxation in this group of countries.

Generally, the interactions with the institutional framework and labor market policies (e.g., minimum wages, unemployment benefits, etc.) are crucial for the effectiveness of these kind of policies which aim at increasing the pay-off from employment122.

The decisive question to assess the cost-effectiveness of financial transfer to workers is whether both objectives are relevant. While the literature has shown the effectiveness in increasing employment and incomes of specific disadvantaged groups, they are costly. And due to various disincentives, they do not generate any (longer-run) positive employment effect123. Especially general equilibrium analyses, e.g., by Lise et al. (2006), have provided evidence for a reversal of the sign of longer-run employment effects and cost-effectiveness compared to partial equilibrium analyses. However, from the perspective of reducing inequality and in-work poverty, these instruments are cost-effective redistribution policies. This holds as far as these transfers are permanent and if wage or income distributions are not compressed124.

The literature and evidence though also raises the question whether a single policy instrument can and should effectively combine redistributive and efficiency aims, since the instruments discussed here have had advantages mainly in one objective or the other125. Marx et al. (2011) point to universal child benefits as an efficient policy – without disincentives – to address redistributive aims. To address the employment objective, other ALMPs are more cost-effective and a better demand-side policies, for example, hiring subsidies and especially labor-supply policies tackling the root of low-skilled workers’ employment problem, namely, policies enhancing their human capital126.

Nonetheless, if applied temporarily in crises within a package of instruments addressing also demand-side incentives, financial transfers to unskilled workers can be an effective redistributive instrument to soften income shortfalls.

The second group of instruments in this category is public works. The original aim of these measures is similar to the previous category of directly raising labor demand, indirectly enhancing labor supply by improving employability and by avoiding skill attrition, indirectly improving labor market matching by signaling of workers’ productivity out of employment and incentivizing workers’ job search efforts127. These original objectives would place this instrument in the second category, but nowadays, this instrument has de facto evolved into a safety net following a clear income support and poverty reduction objective.

Public works temporarily increase employment, but may also increase unemployment by providing incentives to discouraged workers to reenter the labor market and increase their income in public works. A strong locking-in effect is attributed to this instrument128. To avoid more general displacements effects, namely, crowding out private employment through public employment129, the principle of creating additional jobs in public work schemes is focused on low-skilled and labor-intensive publicly useful work130. This feature though eroded the transition effect on human capital, and furthermore, instead of acting as a substitute for employment experience in the private sector, these public works became self-targeting (also due their threat effect), attracting unemployed workers with the lowest employment probabilities and, thus, had a stigmatizing effect131. The role of public employment as a stabilizer during periods of low labor demand was, thereby, undermined; temporary public programs beyond short-term participation are ineffective, and participation may actually lower employment probability132.

The evidence on the ineffectiveness of public works has been widely documented; see, for example, Betcherman et al. (2004) and Martin and Grubb (2001) for an overview or Card et al. (2010), Kluve (2010) and Rodriguez-Planas and Benus (2008) for more recent analyses. Furthermore, the lack of usefulness of public works in generating medium- to longer-run effects is supported by Carling and Richardson (2004) as well as Sianesi (2008), who conclude in their evaluations that the closer an ALMP is to regular work the better its effects for the participants. The evidence from Autor and Houseman (2010) from Detroit’s Work First program cleary underlines the relevance of regular work experience for employment and earnings. Temporary-help job placements had no positive effect on employment and earnings. The so-called direct-hire placements increased workers’ earnings and their employment probability.

This evidence clearly questions public employment creation’s use as an ALMP in light of its significant budgetary costs133, which is reflected in decreasing use of this instrument. Nonetheless, as advantages of public works schemes provision and improvement of basic local infrastructure as well as its role as an income safety-net for the poor are mentioned134. These might explain the sizeable resources spent in OECD countries and, especially with respect to the latter, its heavy use in developing countries135. Public works can act as a temporary safety net during crises in middle income countries targeting the poor and establishing and offering an incentivized compatible low wage136 if existing safety nets cannot be expanded swiftly. As employment of last resort, especially in low income countries, where safety nets are broadly non-existing, public works can establish a self-targeted safety net. These aims of public works though would place it rather as a passive labor market policy than active and reflects a blending of active and passive objectives.

Experiences though have shown that in middle to high income countries, activation policies in interaction with passive labor market policies may provide a role for public works by reducing the payoff from being unemployed. In these cases, the receipt of unemployment benefits or social assistance is conditional on the participation in workfare schemes. This obligation as part of the rights and duties framework of the unemployed, has been particularly effective in Denmark’s flexicurtiy set of policies (generous unemployment support, low firing costs and workfare). The low unemployment rate of Denmark was attributed to this third feature, especially the introduction of workfare activation requirements in tandem with tightening of eligibility for unemployment support and its duration, which raised job search and work incentives for regular work137.

In their general equilibrium framework, Andersen and Svarer (2008) show that beyond the locking-in effect of workfare, workfare also has a threat effect for unemployed workers not activated, who then raise their search effort in light of potential activation, and a negative wage effect on the employed, since it lowers the fallback position of employed workers, which reduces their wage demands, and in turn increases labor demand. Rosholm and Svarer (2008) provide evidence for a strong and significant threat effect, which reduces unemployment duration by three weeks.

Non-participation in ALMP may be sanctioned by, e.g., reducing unemployment benefits. Sanctions represent another instrument targeted at raising distorted search and work incentives, which in contrast has no locking-in effects138. Van den Berg et al. (2004) report significant positive effects of sanctions. Lalive et al. (2005) also show significant quantitatively similar threat effects arising from benefit sanctions on the sanctioned and non-sanctioned. Van der Klaauw and van Ours (2010) show that the outflow from unemployment doubles after sanctions have been imposed139. Calmfors et al. (2001) though point out that program participation may then represent a means for benefit churning, and program volumes may explode.

In sum, financial transfers to workers and public works do not exclusively target an increase of employment but redistribute income to reduce inequality and in-work poverty. The former are cost-ineffective, and, due to various disincentives, they create no (longer-run) positive employment effects. But under certain conditions, they very well might be cost-effective redistribution policies. Public works programs resemble more a fiscal drain and can even have negative effects on the employment probability of participants. Its temporary use targeting poor families is justified as means to combat poverty by providing a safety net. This though raises the question whether public works should not be considered as rather more passive than active labor market policies.

The combination of public works instruments with activation policies as workfare has provided positive results, especially due to the significant threat effects. Sanctions and activation measures in general have been very successful in restoring search and work incentives from unemployment benefits. Imposing sanctions or activation requirements through participation in job search assistance, training or measures closer to regular jobs (along the results from Carling and Richardson, 2004, and Sianesi, 2008) might be a more cost-effective alternative, also in light of the considerable locking-in effect of public works. Bargain and Orsini (2006b) argue that efficient activation instruments could have a greater impact on poverty reduction by bringing workers into employment.

4.4 Incentives for human capital enhancement (Category IV)

ALMPs providing incentives for human capital enhancement are widely used and represent the largest share in governments’ expenditures on ALMPs, and the evaluations show mixed results. A wide array of training and retraining measures are adopted, stretching from basic jobs skills to certified specific vocational skills, from targeting disadvantaged workers to across-the-board programs as well as from offering public classroom training to financing on-the-job training140. These measures aiming at increasing productivity, employability and earnings of workers enhance labor supply by adapting and increasing workers’ skills and improve job matching by tackling skill mismatches141. Boone and van Ours (2004) show theoretically that even if training would not have any impact on the outflow from unemployment, by generating higher quality labor market matches, it will reduce the outflow from employment.

Displacement effects, i.e., trained workers are hired and therefore existing employees are fired, are only likely if the training content would be superior to on-the-job experience, which should be expected to be the opposite. Reviewed evidence by Calmfors et al. (2001) confirms that labor market training programs do not create significant displacement effects. They might though entail sizeable deadweight costs if they finance private training of workers who would have been trained also in absence of this measure. The high cost of these programs often leads to cream-skimming-effects, and by chosing unemployed workers with a higher employment probability deadweight effects are thereby further increased142. As with all ALMPs, targeting plays a crucial role in enabling cost-effectiveness, and detailed rules should minimize caseworkers’ leeway.

Training measures involve strong locking-in effects during participation in the training program; its magnitude is directly related to program duration. Evidence reviewed by Calmfors et al. (2001) suggests that the reduced employment probability during participation may even outweigh the positive treatment effect after participation. Lechner et al. (2005) argue that this result driven by the locking-in effect is due to the focus on the short-run effects and that positive effects need one to three years to materialize143. Their evidence suggests that all training measure increase long-run employability and earnings.

As previous ALMPs, training measures can act as substitutes for work experience (screening effect)144. To maximize the screening as well as the transition effect based on the available evidence, it is important to orientate the training towards current and future skills needs of employers as well as actively involving employers, provide recognized formal qualifications and especially having the training on-the-job145.

While training measures are expected to increase wages146, evaluations show that wages are insignificantly affected. This may be a result of shorter-run evaluations or also be a result of the countervailing competition effect of training, which is expected to be more enduring by increasing outsiders’ human capital147, and thereby increases labor market attachment of disadvantaged workers. The evidence reports most favorable results for training measures targeted at long-term unemployed workers.

Especially on-the-job training has proven to be particularly effective in comparison to classroom training148 — for example Kluve (2010) points out that combining classroom with on-the-job training increases the probability of a positive impact by 30 percent compared with solely classroom training. Lechner et al. (2005) provide results on training assigned by caseworkers misjudging skills and sectoral demands149. This aspect highlights the importance of involving employers, focusing at least partly on an on-the-job training component and providing unemployed workers with the appropriate tools to adapt150.

Reviews by Betcherman et al. (2004), Kuddo (2009) and Martin and Grubb (2001) report that the evidence suggests that tightly targeted training in small size programs for the unemployed have mostly positive impacts on raising employment probabilities151. Rodriguez-Planas (2010) confirm positive impacts of training in Romania for workers’ reemployment probabilities. Arellano’s (2010) evaluation of a Spanish program also suggests a significantly shorter duration of unemployment for trained workers. Kluve’s (2010) meta study confirms the effectiveness of training measures, but as Sianesi (2008), he ranks training measures below ALMPs for providing incentives for employment creation and those improving job matching in terms of effectiveness.

Card et al. (2010), Hotz et al. (2006a, 2006b) as well as Lechner et al. (2005) though point out that the effectiveness of training programs increases significantly in the medium to longer run and that shorter term ranking of policy effectiveness can be overturned, whereby it is crucial to evaluate the long-run implications152.

While being a very costly measure, on-the-job training targeted at long-term unemployed workers seems to be cost-effective. The evidence suggests targeting long-term unemployed workers – due to the implied competition, screening and transition effects – might be very cost-effective in supporting recoveries. Nonetheless, to keep the long-term unemployed attached to the labor market and upgrade their skills, these measures might also be relevant in recessions, though with no shorter-term impact.

4.5 Improved labor market matching (Category V)

ALMPs improving labor market matching are widely used in OECD countries and are considered the most cost-effective ALMPs in increasing job search and matching efficiency153. They can overcome frictional obstacles to employment and alleviate structural imbalances by improving matches and adapting qualifications to employers’ needs154. Besides incentivizing job search of the unemployed, they can avoid discouragement and support labor market attachment. Often measures to improve job matching are combined with various other ALMPs, especially with sanctions, whereby it is sometimes difficult to distill the effects of this policy alone. Furthermore, evaluations generally focus on job search assistance, which leaves little to say about the other instruments, which are expected to have comparable effects155.

While the wide set of short-term measures increases the outflow out of unemployment and decreases the duration of unemployment, it also increases the reservation wage of the workers and may have an upward pressure on wages156. This may be counterbalanced by an increase in labor supply by attracting inactive workers as well as by competition effects since these measures are mainly targeted at outsiders.

Reviews by Calmfors (1994), Martin and Grubb (2001) and Thomsen (2009) as well as studies for example by Card et al. (2010), Kastoryano and van der Klaauw (2011) and Kluve (2010) provide evidence on significant effects of intensified job search assistance for outsiders on their employment probabilities and sometimes earnings, especially for long-term unemployed workers157. Rodriguez-Planas (2010) present evidence on an increase of 20 percent in the employment probability due to job search assistance in Romania, and reviews by Martin and Grubb show an increased probability of outflow from unemployment between 15 and 30 percent158.

While these effects are achievable very swiftly through ALMPs improving job matching in contrast to other ALMPs, for example, those providing human capital enhancement, their effectiveness is concentrated on the short-run and is not as sustainable159. Recent evidence from Blasco and Rosholm (2011) though highlights the existence of the transition effect, whereby improved labor market matching can indeed have longer run implications on workers’ employment probabilities by bringing them into employment.

Displacement effects may exist but can be expected to be small in comparison with other ALMPs160. Nonetheless, measures for improving job matching may entail deadweight costs, if they support workers who would have found a job easily without the support, but this is rarely measured161. Similarly, cream-skimming effects may worsen the effectiveness due to caseworkers’ incentives or the involvement of private agencies, which typically target higher-skilled workers who generally have higher employment probability162. At the same time, caseworkers may also target discouraged workers with very low employment probabilities just to prequalify them for the receipt of unemployment benefits (churning effect)163.

Nonetheless, evidence by Wunsch (2013) underlines that job search assistance should be targeted at unemployed workers with low hiring probabilities, since these are the ones needing assistance in avoiding becoming long-term unemployed164, and beyond that at long-term unemployed workers.

Card et al. (2010), Kastoryano and van der Klaauw (2011) and Wunsch (2013) confirm previous results that ALMPs improving job matching should be applied at the beginning of the unemployment spell. Locking-in effects of these programs are also expected to be minimal165.

To improve the effectiveness via monitoring of search behavior and the willingness to work very often, job search assistance is combined with monitoring and sanctions to increase its effectiveness166. This makes it difficult to separate and attribute the positive effects to improved search and matching efficiency or increased search through threat effects167.

According to the OECD (2010), this category of ALMPs has been scaled up considerably during the crisis, but Cazes et al. (2009) and Kuddo (2009) point out that in the onset of a crisis, when labor demand is very low, improved job matching will not be very effective. Evidence from Dar and Tzannatos (1999) shows this instrument’s ability to strongly support the recovery phase after a deep recession, whereby, it can reduce the lagging behind of employment growth.

The literature, thus, shows that ALMPs improving labor market matching are very cost-effective measures which can have significant short-run effects and should be targeted at workers with low employment probabilities at the beginning of the unemployment spell and at long-term unemployed workers. This targeting minimizes negative effects, and potential churning incentives can be avoided with sanction mechanisms. While these ALMPs are essential for the functioning of the labor market, there are most effective in recoveries.

4.6 Policy overview

Table 2 summarizes the discussed cost-effectiveness, the positive and negative effects and their usefulness in crisis situations and in the normal business cycle.

5 Conclusion

This paper presents a new perspective on how to view active labor market programs (ALMPs) in light of their primary target. To guide evidence-based policy making, we explicitly highlight indirect effects of ALMPs. We show that ALMPs aiming at retaining employment, for example, work sharing schemes, should be used only for very short periods, specifically during severe recessions, and in combination with measures to accelerate take-up. More cost-effective and desirable are the ALMPs creating employment, which redistribute incentives to outsiders in the labor market, whereby their attachment to the labor market is strengthened, the outflow out of unemployment is supported and labor market persistence is reduced. These ALMPs are highly effective during recoveries.

In-work benefits and public works are not very cost-efficient in terms of raising employment, but might be in reducing poverty and inequity. The open question for future research is whether these types of ALMPs are better than passive policies. Policies readjusting distorted employment incentives, such as activation and sanction measures, have proven to provide cost-effective results, especially during normal times.

While generally evaluations of ALMPs tend to deliver mixed results in the short-run, recent studies have shown that longer-term evaluations provide evidence on more positive impacts of policies. ALMPs can be indeed cost-effective from a longer-term perspective (3 to 10 years), and some of them may even be self-financing. These results call for a shift towards long-run evaluations, including following workers’ employment trajectory to better ascertain the impact of individual policies.