Abstract

Background

Natural gas seeps contribute to global climate change by releasing substantial amounts of the potent greenhouse gas methane and other climate-active gases including ethane and propane to the atmosphere. However, methanotrophs, bacteria capable of utilising methane as the sole source of carbon and energy, play a significant role in reducing the emissions of methane from many environments. Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs are a unique group of bacteria that grow on other components of natural gas (i.e. ethane and propane) in addition to methane but a little is known about the distribution and activity of Methylocella in the environment. The purposes of this study were to identify bacteria involved in cycling methane emitted from natural gas seeps and, most importantly, to investigate if Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs were active utilisers of natural gas at seep sites.

Results

The community structure of active methane-consuming bacteria in samples from natural gas seeps from Andreiasu Everlasting Fire (Romania) and Pipe Creek (NY, USA) was investigated by DNA stable isotope probing (DNA-SIP) using 13C-labelled methane. The 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved from DNA-SIP experiments revealed that of various active methanotrophs, Methylocella was the only active methanotrophic genus common to both natural gas seep environments. We also isolated novel facultative methanotrophs, Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 from Pipe Creek, able to utilise methane, ethane, propane and various non-gaseous multicarbon compounds. Functional and comparative genomics of these new isolates revealed genomic and physiological divergence from already known methanotrophs, in particular, the absence of mxa genes encoding calcium-containing methanol dehydrogenase. Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 had only the soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) and lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenase (XoxF). These are the first Alphaproteobacteria methanotrophs discovered with this reduced functional redundancy for C-1 metabolism (i.e. sMMO only and XoxF only).

Conclusions

Here, we provide evidence, using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods, that Methylocella are abundant and active at terrestrial natural gas seeps, suggesting that they play a significant role in the biogeochemical cycling of these gaseous alkanes. This might also be significant for the design of biotechnological strategies for controlling natural gas emissions, which are increasing globally due to unconventional exploitation of oil and gas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Methane, a potent greenhouse gas, is one of the most significant contributors to climate change. Emissions since the Industrial Revolution have driven a large increase in the atmospheric concentrations of methane, currently around 1.8 ppm, an increase by a factor of 2.6 from pre-industrial times [www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends_ch4/]. Globally, approximately 600–900 Tg of methane is emitted annually from various natural and anthropogenic sources [1]. Based on the process of methane synthesis, it can be categorised as arising from two origins. Firstly, biogenic methane is produced by methanogenic archaea, under anaerobic conditions, mainly in wetlands, landfill sites, rice paddies, the rumen of cattle and the hindgut of termites. Secondly, methane is produced from the thermogenic decay of sedimentary organic material, resulting in a mixture of methane and other gases commonly known as natural gas. The origin of methane-rich gas can be determined by its chemical composition and by measurement of the stable isotopic ratios of carbon (C) and hydrogen [2, 3].

Natural gas is emitted to the atmosphere from subsurface reservoirs, through natural seepage or during mining and extraction of coal and hydrocarbons. These sources contribute a significant amount of methane (42–64 Tg year−1) and other climate-active gases, e.g. ethane (a photochemical pollutant, 2–4 Tg year−1) and propane (an ozone precursor, 1–2.4 Tg year−1) [4, 5]. Seepage of natural gas occurs over a wide range of terrestrial hydrocarbon-prone sedimentary basins, both as visible features including dry gas seeps and mud volcanoes, hot and cold springs, alkaline soda lakes and volcanic systems [2, 6,7,8,9,10,11] and also as diffused and frequently undetected microseepage [12]. In marine environments, natural gas is emitted from deep sea hydrothermal vents and shallow marine methane seeps [13, 14]. Terrestrial natural gas seeps have been reported for centuries in many regions, including the Appalachian Basin in the USA [15,16,17], represented by towns such as Gasport (Niagara County, USA), thus named in 1826. Many of these seeps emit natural gas, which can be ignited [18]. Recently a seep, reputedly known to Native Americans thousands of years ago, named the “Eternal Flame” (Chestnut Ridge National Park USA) was highlighted, where remarkable releases of natural gas were observed [19]. The gas released from this site contains methane (60%, v/v) plus ethane (23%, v/v) and propane (12%, v/v) [19]. Human activities have also caused major natural gas releases, e.g. the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010 released 170,000 t of natural gas [20]. Geological events such as thawing glaciers [21], as well as the exploitation of unconventional oil and gas reserves, including shale gas extraction (fracking) are predicted to increase the release of geological methane, with accompanying concerns of environmental pollution and climate change [22,23,24,25].

However, methanotrophic bacteria, a unique group of microbes that utilise methane as their sole source of C and energy, can consume methane before it reaches the atmosphere and have been reported to mop up over half of the methane produced by methanogens in wetlands [26,27,28]. Phylogenetically, most aerobic methanotrophs belong to the phyla Proteobacteria (Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria) and Verrucomicrobia (although Verrucomicrobia comprises both methanotrophs and non-methanotrophs, preventing designation as methanotrophs by taxonomy alone in this case). They contain the enzyme methane monooxygenase (MMO) which catalyses the oxidation of methane to methanol [29]. There are two types of MMO: a copper-containing, membrane-bound, particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) and a diiron centre-containing, cytoplasmic, soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) [29,30,31,32]. After the initial oxidation of methane to methanol, methanol dehydrogenase oxidises methanol to formaldehyde, which can be assimilated to cell carbon or further oxidised to formate and CO2 for energy generation [31]. There are two types of methanol dehydrogenase common in methanotrophs; a calcium-containing enzyme encoded by the mxa gene cluster and a lanthanide-containing variant (XoxF) encoded by xoxF [33,34,35]. Although xoxF genes were detected in methanotrophs many years ago, their function was not established until the discovery of the role of lanthanides (rare earth elements) as co-factors [36]. Recently, several studies have shown that lanthanides regulate the expression of both types of methanol dehydrogenases in methanotrophs [37,38,39,40,41,42] and methylotrophs [43,44,45,46]. These findings confirm that lanthanide-containing XoxF is also environmentally important, in addition to the calcium-containing methanol dehydrogenase [35, 47].

Methanotrophs were considered obligate for decades until the discovery of Methylocella, a facultative genus capable of growing on several multicarbon compounds in addition to methane [48, 49]. Methylocella belong to the family Beijerinckiaceae (Alphaproteobacteria) that comprises diversified heterotrophs ranging from generalist organotrophs (e.g. Beijerinckia indica) to facultative methanotrophs (e.g. Methylocella silvestris) and obligate methanotrophs (e.g. Methylocapsa acidiphilia) [50]. Recently, some more limited facultative methanotrophs of the genera Methylocystis and Methylocapsa, which can grow on ethanol or acetate in addition to C-1 substrates, have been described [51,52,53,54]. Analysis of the genome of Methylocella silvestris BL2 revealed that, unlike most methanotrophs, Methylocella uses only the sMMO to oxidise methane and does not contain the pMMO [55]. For decades, ecological studies, which often rely on the pMMO gene markers, have identified obligate methanotrophs as prevalent in environments rich in methane emissions [56, 57] and with the exception of a few previous studies [58, 59] little is known about the distribution of Methylocella in the environment.

Microbes growing on other components of natural gas, such as ethane and propane, include mainly Actinobacteria (e.g. Rhodococcus, Nocardioides and Mycobacterium) [60,61,62,63], Gammaproteobacteria (Pseudomonas) [64] or Betaproteobacteria (Thauera) [65, 66]. Many propanotrophs contain a propane monooxygenase (PrMO) enabling growth on ethane and propane [67, 68]. Propanotrophs are metabolically versatile compared to methanotrophs, and grow on a range of multicarbon compounds, but not methane [67]. PrMO of propanotrophs and sMMO of methanotrophs form two distinct groups within a large family of enzymes known as soluble di-iron monooxygenases (SDIMOs) [69,70,71].

Methylocella silvestris BL2 also contains a PrMO and can grow on methane and propane simultaneously using sMMO and PrMO [49]. The metabolic versatility of Methylocella to utilise several components of natural gas is unique and suggests a potentially significant role for Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs in the biogeochemical cycling of natural gas in the environment. We hypothesised that less versatile obligate methanotrophs and propanotrophs at natural gas seep sites may be at a competitive disadvantage compared to Methylocella. Terrestrial natural gas seeps have been largely ignored in the past in terms of methanotrophic studies [72,73,74] compared to the studies targeting marine hydrocarbons seeps [75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. Recently, we reported that Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs are abundant at natural gas seep sites [59]. However, these data did not reveal the activity of abundant taxa. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify the active microbes involved in cycling natural gas methane and determine if Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs are active at terrestrial seep sites, using both culture-dependent and culture-independent methods.

Results and discussion

Active methanotrophs at terrestrial natural gas seeps revealed by DNA stable isotope probing (DNA-SIP)

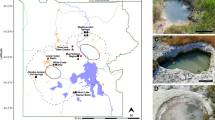

We sampled two different natural gas seeps reported to emit thermogenic natural gas containing methane, ethane and propane; Andreiasu Everlasting Fire, Romania, with a slightly basic pH (pH 8.2), and Pipe Creek, New York, USA, with slightly acidic pH (pH 6.0) [7, 18, 59]. Amplicon sequencing targeting the 16S rRNA gene in DNA samples isolated directly from these environments was performed to investigate the native bacterial community of the seep sites. Sequence analysis showed that out of 12 phyla at an abundance of higher than 1%, Proteobacteria (alpha, beta and gamma), Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Chloroflexi formed the major part (> 70%) of native bacterial communities in unenriched environmental samples (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Dominant taxa included Sideroxydans (Pipe Creek) and Mycobacterium (Andreiasu Everlasting Fire) when analysed at the genus level (Fig. 1). As reported previously [59], among methanotrophs, Methylocella and Methylocapsa dominated in samples from Pipe Creek while Methylococcus and Methylocella were the most abundant methanotrophs in Andreiasu Everlasting Fire (Fig. 1). Verrucomicrobia were also abundant in samples from Andreiasu Everlasting Fire, but cannot be definitively identified as methanotrophs based on 16S rRNA gene phylogeny. Comparatively, the relative abundance of Methylocella was higher at Pipe Creek (5.92% ± 0.1) than at Andreiasu Everlasting Fire (1.89% ± 0.01). Interestingly, the proportion of ethane and propane in the natural gas released from the Pipe Creek seep (22% v/v, ethane and propane) was also several times higher than in the gas released from Andreiasu Everlasting Fire (3% v/v, ethane and propane) [7, 18, 59]. This suggested that increased ethane and propane content of natural gas might favour Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs to colonise natural gas seep sites [59, 82].

Relative abundance of bacterial genera in native environmental samples from Pipe Creek and Andreiasu Everlasting Fire, based on 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Genera with a relative abundance of higher than 5% are shown in bold and with an asterisk (*). 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence data for Andreiasu Everlasting Fire were reported in Farhan Ul Haque et al. [59]

The community structure of active methane-consuming bacteria in samples from natural gas seep sites was investigated by DNA-SIP [83], using 13C-methane incubations in parallel with 12C-methane incubations (as control) at two time points (determined by incorporation of total methane consumed, i.e. 100 and 200 μmol methane utilised per gram sample). Rates of consumption of 13C-methane or 12C-methane observed in these samples from natural gas seeps (Fig. 2, Table 1) were faster than those reported for biogenic methane consumption in agricultural wetlands [84, 85]. This suggests that these natural gas seep sites may be hotspots for methane oxidation and potentially a large active biological sink for methane. DNA recovered from CsCl fractions of SIP incubations revealed that 200 μmol methane utilised per gram of sample (approximately 100 μmol C assimilated to biomass per gram of sample) resulted in the incorporation of sufficient 13C label for a successful DNA-SIP experiment (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

Consumption of methane by environmental samples from natural gas seep sites of Pipe Creek (a) and Andreiasu Everlasting Fire (b). Microcosms containing environmental samples were incubated under 13C-methane (red circles) or 12C-methane (blue circles) as the only sources of C or energy without any supplementary nutrients. The total amount of methane was injected into the headspace in two spikes (approximately 100 μmol/gram of fresh sample per spike). Data points show the mean (with error bars showing the standard errors) of duplicate incubations for each substrate

The 16S rRNA gene sequences retrieved by PCR from heavy and light DNA fractions of 13C-methane- and 12C-methane-incubated samples were resolved into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at the genus level. Eighteen OTUs (Pipe Creek) and 14 OTUs (Andreiasu Everlasting Fire) were found at a relative abundance of greater than 1% in heavy DNA fractions retrieved from 13C-methane-incubated samples (Fig. 3). Taxa were identified as being 13C-labelled based on their relative abundance in heavy and light fractions of incubations with 13C-methane, as compared with 12C-methane controls (as described in the “Materials and methods” section). The relative abundance of labelled taxa constituted 51.84% and 51.65% of the total in Pipe Creek and Andreiasu Everlasting Fire, respectively. Sequences affiliated with the genera Methylocella (30.3%), Verrucomicrobium (24.8%) Methylobacter (11.1%), Methylocapsa (10.0%) and Methylocystis (5.5%) were detected in 13C-labelled DNA obtained from DNA-SIP experiments with samples from Pipe Creek (Fig. 3), identifying Methylocella as the most abundant active methanotroph at this site. Methylocella were also 13C-labelled in Andreiasu Everlasting Fire DNA-SIP samples and constituted 3.5% of 13C-labelled taxa along with the methanotrophs Crenothrix (28.9%), Methyloglobulus (14.6%) and Methylosinus (3.6%) (Fig. 3). Hyphomicrobium and Methylobacterium were the only non-methanotrophs identified as 13C-labelled in DNA-SIP experiments with Pipe Creek samples, while in DNA-SIP experiments with Andreiasu Everlasting Fire samples, non-methanotrophic bacteria labelled with 13C were Hyphomicrobium, Rhodospirillum, Micavibrio and Bdellovibrio (Fig. 3). Hyphomicrobium and Methylobacterium are methylotrophic bacteria and may have been feeding on methanol released during methane utilisation by methanotrophs [86]. Micavibrio and Bdellovibrio are bacterial predators that might also have been cross-feeding on active methanotrophic bacteria. The presence and labelling of methylotrophs suggest that methanotrophs are supporting a community of non-methane oxidisers in these environments. Our data show that Methylocella was the only active methanotrophic genus common to both environments. Previously, Methylocella were detected in environmental samples originating from acidic forest soils and acidic peatlands as reported in a few cultivation-independent [87,88,89,90] and cultivation-dependent studies [54, 91,92,93,94,95,96]. Studies focussing on functionally active methanotrophs (for example [97,98,99,100]) also detected Methylocella in acidic environments leading to the belief that Methylocella were mainly confined to acidic environments, although, interestingly, some studies reported that Methylocella were also abundant in alkaline environments [58, 59, 101]. Our observation that Methylocella are active methanotrophs in environmental samples from geological natural gas-emitting sites of acidic and basic pH suggest that its metabolic flexibility gives Methylocella a competitive advantage over other methanotrophs to utilise methane and other short-chain alkanes in such environments.

Community profile of the enriched heavy (C-13 H) and light (C-13 L) DNA fractions of 13C-methane incubations from DNA-SIP experiment with the Pipe Creek samples (a) and Andreiasu Everlasting Fire samples (b), analysed by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. Sequencing community profiles of heavy (C-12 H) and light (C-12 L) fractions of control incubations with 12C-methane are also presented. Taxa represented by black borders and in parenthesis are identified as “13C-labelled” in that experiment. Taxa present at a relative abundance lower than 1% in any replicate of C-13 H fraction are included in “Others”. Data presented here are the mean of biological duplicates

Targeted isolation of facultative methanotrophs

As indicated above, culture-independent DNA-SIP experiments showed that Methylocella-like facultative methanotrophs were one of the most abundant and active methanotrophs at the natural gas seeps. To complement these results, we isolated facultative methanotrophs capable of utilising methane, ethane and propane as their only source of carbon and energy. Enrichments of environmental samples from the seep sites were incubated under a mixture of methane, ethane and propane (in a proportion comparable to the gas released from Pipe Creek). Serial dilutions of enrichment cultures were plated and incubated under the gas mixture, and colonies were screened for parallel growth on each gas separately. We isolated two bacterial strains growing under these gases, both as a mixture and individually (Table 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 from Pipe Creek exhibited faster growth rates on methane and propane (up to 0.04 h−1, Table 2) compared to those previously reported for Methylocella (0.01–0.02 h−1 on methane and 0.005–0.015 h−1 on propane) [49, 102, 103]. As with Methylocella silvestris BL2 [49], they grew under methane and propane simultaneously and could also utilise non-gaseous multicarbon compounds, including acetate, pyruvate and succinate (Additional file 1: Table S1). The isolates grew faster on ethane compared to their growth on methane or propane (Table 2, Additional file 1: Figure S3), as the only source of C and energy. Since these isolates were from an environment rich in ethane [18, 59], they may have been adapted to ethane utilisation and, hence, can utilise the major components of natural gas and serve as a natural biofilter for the various geological gases before they are emitted from terrestrial natural gas seep sites to the atmosphere.

Functional genomics and comparative genomics of Methylocella isolates

Analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene revealed that strains Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 were most closely affiliated with Methylocella tundrae (Fig. 4). Previously, complete genomes of only three strains of Methylocella have been reported, belonging to Methylocella silvestris and Methylocella tundrae species [55, 104, 105]. Genome sequencing and in silico DNA-DNA hybridization analyses suggest that these novel Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 strains represent subspecies of Methylocella tundrae distinct from Methylocella tundrae T4 strain (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA sequences from new Methylocella isolates (bold red) along with other known Methylocella (bold black) strains. Accession number for the nucleotide sequences are given in brackets. Sequences were aligned using Mega 7.0 and the optimal tree (drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site) with the sum of branch length = 0.65 is shown where the evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method (1067 positions in the final dataset)

PCR analyses as well as genome sequence analysis of the isolates showed that the mmoX gene (encoding MmoX, the alpha subunit of sMMO) is present while the pmoA gene (encoding the alpha subunit of pMMO) is absent. This is in agreement with previous reports of Methylocella [55, 104]. Apart from Methylocella, the obligate methanotrophs Methyloceanibacter [106] and Methyloferula stellata [107], also lack pMMO and rely on sMMO for methane oxidation.

Detailed analyses of the genomes revealed the presence of the genes of the soluble methane monooxygenase (mmo operon genes), in both isolates (Fig. 5). In contrast to Methylocella silvestris BL2 that has only one copy of the mmo operon, two complete mmo operons are present in Methylocella sp. PC4 (Fig. 5). To our knowledge, having multiple copies of mmo operons is unique to this novel Methylocella sp. PC4 isolate compared to other extant Methylocella strains. The mmo operons in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 are highly conserved and of high similarity to those present in Methylocella silvestris BL2 (Fig. 5). The structural genes for sMMO (mmoXYBZDC) are adjacent to regulatory genes encoding a σ54 transcriptional regulator (mmoR) and a putative GroEL-like chaperone (mmoG), respectively.

a The soluble methane monooxygenase genes in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 isolates compared with their homologues in Methylocella silvestris BL2. Names of the genes are given above, and amino acid identities to their homologous proteins in Methylocella silvestris BL2 are shown in brackets. b Phylogenetic analysis of MmoX (alpha subunit of soluble methane monooxygenase) from new Methylocella isolates (bold red) along with MmoX from other known Methylocella (bold black) strains based on the derived amino acid sequences. Protein names and accession numbers for the sequences are given in brackets. Amino acid sequences were aligned using Mega 7.0 and the optimal tree (drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site) with the sum of branch length = 0.53 is shown where the evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method (392 positions in the final dataset). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) ranged from 59 to 100

Methanol dehydrogenase, the second essential enzyme for methane metabolism, catalyses the conversion of methanol to formaldehyde during C-1 metabolism. Surprisingly, Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 lacked the mxa gene operon encoding the classical calcium-containing methanol dehydrogenase. Instead, multiple copies of the xox gene clusters encoding for a lanthanide-containing methanol dehydrogenase XoxF and associated proteins (XoxJ and XoxG) were present (Fig. 6a). Two complete xox gene operons (xoxFJG) phylogenetically related to XoxF5 and XoxF3 clades [108] are present (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Absence of calcium-containing methanol dehydrogenase in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 was confirmed by failure to PCR-amplify mxaF, encoding the alpha subunit (Fig. 6b). Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 showed very poor growth with methanol as the only source of C and energy when grown without adding lanthanides in the growth medium (Fig. 6c), confirming lanthanide-dependence under these conditions. All Methylocella strains and other methanotrophs described to date contain the classical calcium-containing methanol dehydrogenase, usually in addition to the lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenase(s) [33, 34, 47], with the exception of the Verrucomicrobium methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV [36] and two gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs [109]. The recently discovered role of lanthanides in the activity and regulation of methanol dehydrogenase had prompted us to use lanthanum as a regular nutrient in the medium for enrichment and isolation of methanotrophs, which facilitated the isolation of novel Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 isolates containing only lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenase. To our knowledge, these are the first alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs which do not contain a calcium-containing methanol dehydrogenase.

a Gene clusters encoding for the two types of lanthanide-dependent methanol dehydrogenases XoxF3 and XoxF5 in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4. Names of the genes are given above. Another copy of xoxF5 is also present in the genomes of Methylocella PC1 and PC4, but only as a singleton gene (see Additional file 1: Figure S4). b PCR amplification showing the absence of mxaF in Methylocella sp. PC1 (lane 1) and Methylocella sp. PC4 (lane 2) along with positive control Methylocella silvestris BL2 (lane 3) and no template control (lane 4). Lane M represents 1 kb DNA ladder. c Growth of Methylocella sp. PC4 with (red) and without (blue) lanthanum. Cultures were grown in DNMS medium with methanol (20 mM) as the only source of carbon and energy. Each point shows the average of duplicate cultures with error bars (invisible if smaller than symbol size) showing the standard errors. A control without any carbon substrate showing no growth of cells (green) was also performed

In addition to mmo and xox gene operons, other genes required for the central metabolism of C-1 substrate were also analysed (Additional file 1: Table S3). A complete set of genes encoding enzymes required to convert formaldehyde into formate via tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) pathway was found (Additional file 1: Table S3), and the genes (mtdA and fchA encoding methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase and methenyl-tetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase, respectively) required to convert formaldehyde into formate via the tetrahydrofolate (H4F) pathway were not found, but instead folD, encoding bifunctional 5,10-methylene-H4F dehydrogenase/methenyl-H4F cyclohydrolase, was present. For oxidation to CO2, genes encoding molybdenum-containing formate dehydrogenase (FDH2) [110] were found (Additional file 1: Table S3). To assimilate formaldehyde into biomass, the genes encoding enzymes of the serine cycle were present in both isolates (Additional file 1: Table S3). Our comparative genomic analyses show that the pathway for the assimilation and oxidation of formaldehyde from C-1 substrates to produce biomass and energy is similar in these isolates to that of Methylocella silvestris BL2 (Additional file 1: Table S3).

The genomes of Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 contained genes (prmABCDGR) encoding PrMO, a SDIMO enzyme responsible for the growth of bacteria on short-chain alkanes (Fig. 7a). Genes encoding PrMO in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 share identities (> 78% based on AA sequences) with those found in Methylocella silvestris BL2. Methylocella silvestris BL2 and Methylocella silvestris TVC are the only strains described previously, capable of growing on methane and propane and containing both sMMO and PrMO [55, 104]. Interestingly, and in contrast to other Methylocella strains, isolates Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 contain more divergent copies of gene clusters putatively encoding another SDIMO in addition to PrMO and sMMO. BLAST and phylogenetic analyses reveal that these gene clusters (here named as bmoXYBZDCG in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4) are more similar to the bmo genes encoding butane monooxygenase found in Thauera butanivorans (Fig. 7b, c) [111, 112]. Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 did not grow with butane as the only source of carbon and energy. The reason could be that this bmo-like gene cluster in both Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 lacks bmoR and istAB genes (Fig. 6b). BmoR is putatively involved in the regulation of butane monooxygenase and was required for good growth of Thauera butanivorans on butane [112]. However, the presence of multiple SDIMOs in the genomes of Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4, in particular, sMMO and PrMO enabled them to grow on methane as well as on ethane and propane, the major components of fugitive nature gas. This report is to our knowledge the first to describe and to isolate novel strains of facultative methanotrophs from natural gas seep sites. Considering the extent of gas seeps spread over Earth’s terrestrial regions, this finding has profound implications for the biological consumption of natural gas and carbon cycling in these environments, which have been ignored in the past.

a Gene operon encoding the propane monooxygenase in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 compared with their homologues in Methylocella silvestris BL2. Names of the genes are given above and amino acid identities to their homologous proteins in Methylocella silvestris BL2 are shown in brackets. b Gene operon putatively encoding butane monooxygenase in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 compared with their homologues in Thauera butanivorans. c Phylogenetic analysis of the alpha subunit of propane monooxygenase (PrmA) and putative butane monooxygenase (BmoX) from Methylocella PC1 and PC4 isolates (red and blue, respectively). PrmA and BmoX from known closely related strains (bold black) and other soluble diiron monooxygenases (ThmA, alpha subunit of tetrahydrofuran monooxygenase; Blr3677 and Rsp2792, putative monooxygenases; PmoC, alpha subunit of propene monooxygenase; MmoX, alpha subunit of methane monooxygenase; DmpN, alpha subunit of phenol hydroxylase; TomA3, alpha subunit of toluene ortho-monooxygenase; IsoA, alpha subunit of isoprene monooxygenase; and TouA, toluene o-xylene monooxygenase component) from different bacteria are also presented. Compressed MmoX sequences are same as the known methane monooxygenases presented in Fig. 5b. Protein names and accession number for the sequences are given in brackets. Amino acid sequences were aligned using Mega 7.0 and the optimal tree (drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site) with the sum of branch length = 5.7 is shown where the evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour-joining method (316 positions in the final dataset). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) ranged from 60 to 100

Conclusion

Here, we provide evidence, using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods, that Methylocella are abundant and active at terrestrial natural gas seeps. Methylocella were the only active methanotroph found in both of the contrasting natural gas seep sites tested, suggesting that they play a significant role in biogeochemical cycling of these gaseous alkanes and may serve as a natural biofilter for gaseous hydrocarbons of geological sources before they are emitted to the atmosphere.

We also isolated novel Methylocella isolates with considerable differences to extant strains, illustrating that natural gas seeps may be a rich source of new methanotrophs. Using lanthanum as a nutrient in medium for the enrichment of cultures from the natural gas seep sites we isolated Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4, which contain only XoxF methanol dehydrogenase. Our comparative genomic and growth data suggest that the ability of Methylocella strains to utilise methane as well as short-chain alkanes, integral components of natural gas, is not restricted to one species.

The bacteria obtained in this study provide novel experimental models for investigating the complexity and function of the facultative methanotrophic community active at terrestrial natural gas seeps. This would also be of significance for the design of environmental biotechnological strategies for controlling natural gas emissions along with industrial applications for converting these gases to value-added products, as natural gas emissions are increasing globally due to unconventional oil and gas extraction.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals and reagents (purity, > 99%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated. Buffers, culture media and solutions were prepared in ultra-pure water, and sterilisation was done by autoclaving (15 min, 121 °C, 1 bar) or by filtration (0.2 μm).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Modified diluted nitrate mineral salt (DNMS) medium [49] supplemented with 5 μM lanthanum (LaCl3) was used as a growth medium in 120 ml serum vials (with 20 ml culture volume), with substrate gas as the only source of C and energy. Methane (20%), ethane (10%) and propane (10%), individually or in a mixture at varying concentrations, were injected (percentage v/v in headspace) in sealed serum vials as C substrates. The growth of liquid cultures was monitored by measuring the optical density at 540 nm. Concentrations of substrate gases in the cultures were quantified using a gas chromatograph (GC) using an Agilent 7820A GC equipped with a Porapak Q column (Supelco) coupled to a flame ionisation detector (FID) to measure methane, ethane and propane concentrations as previously described [49]. Comparison of growth of Methylocella sp. PC4 with and without lanthanum (Fig. 6) was performed in 50 ml polypropylene falcon tubes (with 15 ml culture volume) to avoid any contamination of lanthanides from glassware. As many methanotrophs do not store well frozen [113], cultures were maintained on plates or in liquid.

Sample collection

Two different natural gas seep sites, (Andreiasu Everlasting Fire, Romania (Additional file 1: Figure S1B), with a slightly basic pH (8.2), and Pipe Creek, New York, USA (Additional file 1: Figure S1B), with slightly acidic pH (6.0)) with varying characteristics of physical nature, pH and the proportion of methane, ethane and propane in the gas released, were sampled as described previously [59]). Two to five sub-samples, taken from each site in sterile 50 ml plastic tubes, were pooled together in the lab before further experiments were carried out.

DNA-SIP incubation, DNA extraction and fractionation

For DNA-SIP experiments, approximately 2 g of soil/sediment suspensions (1:3 environmental samples and water ratio) in sterile ultra-pure molecular biology grade water without any nutrient supplements were incubated in 120 ml sealed serum vials. Substrate gas (12C-methane or 13C-methane) was injected into the headspace of each serum vial at 1% concentration (v/v) and consumption was followed over time by GC. Time point 1 samples from DNA-SIP incubations were harvested after they had consumed approximately 1% (v/v) added gas, and for time point 2 samples, 12C-methane or 13C-methane was replenished by injecting an extra 1% (v/v) of gas and then harvested after approximately 2% (v/v) of total gas had been consumed. Samples were harvested in order to obtain time points based on 0, 1% (v/v) and 2% (v/v) 12C-methane or 13C-methane gas consumed, corresponding to 0, 100 and 200 μmol C consumed per gram of fresh sample, respectively. All incubations were carried out in duplicate for each substrate and for each time point. Samples were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min in 50 ml falcon tubes. Supernatants were discarded and the soil/sediment pellets were stored at − 20 °C and used later for DNA extraction. DNA was extracted from unenriched environmental samples and SIP-incubated samples using the FAST DNA spin kit for soil (MP Biomedicals), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Quality and quantity of DNA was checked by Qubit (Invitrogen) and NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Labelled and unlabelled DNA from SIP-incubated samples were separated by density gradient ultracentrifugation and fractionation (12 fractions per sample) as described previously [114]. The quantity of DNA retrieved from each fraction was plotted against the corresponding refractive index, quantified using a refractometer (Reichert AR200, Reichert Analytical Instruments, Buffalo, NY, USA) (Additional file 1: Figure S2). Based on the data shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2, three to four fractions of each sample containing labelled DNA (refractive index range 1.4032–1.4045) were mixed and designated as the “heavy” DNA fraction, while two to three fractions of each sample containing unlabelled DNA (refractive index range 1.4015–1.4025) were mixed and designated as the “light” DNA fraction.

Illumina Mi-Seq sequencing of PCR amplicons

PCR amplicons of 16S rRNA gene obtained from the unfractionated unenriched environmental DNA samples and the heavy and light DNA fractions from 12C-methane- or 13C-methane-incubated samples, were sequenced using the Illumina Mi-Seq sequencing platform of MR DNA (Shallowater, TX, USA). Universal primers 341F and 785R [115] targeting the V3 and V4 regions were used to PCR amplify 16S rRNA gene fragment in a reaction volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 μl 2x PCRBIO Ultra Polymerase (PCR BIO), 1 μl of each of forward and reverse primers (10 μM) and 2 μl of template DNA. The cycling conditions were 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 20 sec, 55 °C for 20 sec, 72 °C for 30 sec, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products from duplicate reactions for each fraction were pooled before purifying using a NucleoSpin gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel). The quality and quantity of purified PCR products was assessed by gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop and then concentrations of all PCR products were adjusted to 15–20 ng/μl. DNA libraries following the Illumina TruSeq DNA library protocol from purified PCR products were prepared and sequenced. Sequence data from 16S rRNA amplicons was processed using the MR DNA proprietary analysis pipeline (www.mrdnalab.com) as described previously [59]. Briefly, barcode and primer sequences were removed and then short sequences < 200 bp, sequences with ambiguous base calls and sequences with homopolymer runs exceeding 6 bp were removed. After denoising of the sequences, 16S rRNA gene OTUs were defined with clustering at 3% divergence (97% identity) followed by removal of singleton sequences and chimaeras [116,117,118,119,120,121]. BLASTn against a curated database derived from GreenGenes, RDPII and NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, http://rdp.cme.msu.edu) was used for the final taxonomic classification of OTUs into each taxonomic level. Taxa fulfilling the following criteria were identified as labelled: (1) the relative abundance in the heavy DNA fraction of the 13C-methane-incubated sample was higher than 1.0%, (2) the abundance in the heavy DNA fraction of the 13C-methane-incubated sample was higher than the abundance in the light DNA fraction of the 13C-methane and (3) the difference in the abundance in the compared heavy and light DNA fractions of the 13C-methane-incubated sample was higher than that of the 12C-methane-incubated sample.

Enrichment cultures, isolations and genome sequencing of new Methylocella isolates

Fresh samples (1 g) from the Pipe Creek natural gas seep site were incubated in 10 ml DNMS medium supplemented with 5 μM lanthanum in 120 ml sealed serum vials. A mixture of gases (20%, v/v) in the headspace was injected as the only supplemental source of C and energy comprising of methane, (70%, v/v) ethane (10%, v/v) and propane (20%, v/v), and the vials were incubated in a shaker (150 rpm) at 25 °C for 3 weeks in the dark. Then, serial dilutions (1/10 times) of the enrichment cultures were plated onto DNMS agar plates (supplemented with 5 μM lanthanum), and incubated again under a mixture of gases (10%, v/v) injected into the headspace containing methane (70%, v/v) ethane (10%, v/v) and propane (20%, v/v) in a sealed jar. After 2 weeks of incubation, isolated colonies appearing on the plates were resuspended in 20 μl sterile DNMS medium individually. Each colony suspension was replica-plated onto three plates of DNMS medium (supplemented with 5 μM lanthanum) and incubated under methane, ethane or propane individually in the headspace (10%, v/v) as the only source of carbon and energy. Colonies growing under all three gases were considered as facultative methanotrophs. These facultative methanotrophs were purified by serial dilution of cultures and transfer of single colonies several times on agar plates. Purity of cultures was confirmed by microscopy of cultures, multiple cloning and sequencing of 16S rRNA and mmoX genes and subsequent genome sequencing. The genome sequences were checked for completeness and contamination using CheckM [122]. Upon mapping of raw reads to the assembly using Bowtie2 (v. 2.3.4.1) [123], ~ 99% of all reads aligned to the genome, thus confirming purity of these new Methylocella strains (Additional file 1: Table S5). Genomic DNA from Methylocella strains was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and used for PCR analyses to generate 16S rRNA, mmoX, mxaF, pmoA and prmA amplicons using specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S4). Genome sequencing of Methylocella PC1 and PC4 was performed at MicrobesNG (Birmingham, UK) using Illumina HiSeq technology and assembled using SPAdes 3.7 into contigs (Additional file 1: Table S5). Genome sequence annotation, exploration and comparative genomics of various Methylocella strains were performed using MicroScope, an online platform by GenoScope (France) providing a collection of bioinformatic tools [124].

Availability of data and materials

Amplicon sequence data generated in this study were deposited to sequence read archives (SRA) under project number PRJNA525613 and the genome sequence assemblies have deposited to European Nucleotide Archives under project numbers PRJEB31473 and PRJEB31475. Strains are available from JCM/MFUH on request.

References

Saunois M, Bousquet P, Poulter B, Peregon A, Ciais P, Canadell JG, Dlugokencky EJ, Etiope G, Bastviken D, Houweling S, et al. The global methane budget 2000–2012. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2016;8:697–751.

Etiope G, Feyzullayev A, Baciu CL. Terrestrial methane seeps and mud volcanoes: a global perspective of gas origin. Mar Pet Geol. 2009;26:333–44.

Etiope G. Natural gas seepage; the Earth’s hydrocarbon degassing. Springer Nature; 2015.

Etiope G, Ciccioli P. Earth’s degassing: a missing ethane and propane source. Science. 2009;323:478.

Dalsøren SB, Myhre G, Hodnebrog Ø, Myhre CL, Stohl A, Pisso I, Schwietzke S, Höglund-Isaksson L, Helmig D, Reimann S, et al. Discrepancy between simulated and observed ethane and propane levels explained by underestimated fossil emissions. Nat Geosci. 2018;11:178–84.

Baciu C, Caracausi A, Etiope G, Italiano F. Mud volcanoes and methane seeps in Romania: main features and gas flux. Ann Geophys. 2007;50:501–11.

Baciu C, Ionescu A, Etiope G. Hydrocarbon seeps in Romania: gas origin and release to the atmosphere. Mar Pet Geol. 2018;89:130–43.

Tassi F, Fiebig J, Vaselli O, Nocentini M. Origins of methane discharging from volcanic-hydrothermal, geothermal and cold emissions in Italy. Chem Geol. 2012;310-311:36–48.

Kroeger KF, di Primio R, Horsfield B. Atmospheric methane from organic carbon mobilization in sedimentary basins — the sleeping giant? Earth-Sci Rev. 2011;107:423–42.

Oremland RS, Miller LG, Whiticar MJ. Sources and flux of natural gases from Mono Lake, California. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1987;51:2915–29.

Fiebig J, Hofmann S, Tassi F, D’Alessandro W, Vaselli O, Woodland AB. Isotopic patterns of hydrothermal hydrocarbons emitted from Mediterranean volcanoes. Chem Geol. 2015;396:152–63.

Etiope G, Klusman RW. Microseepage in drylands: flux and implications in the global atmospheric source/sink budget of methane. Glob Planet Chang. 2010;72:265–74.

Kawagucci S, Okamura K, Kiyota K, Tsunogai U, Sano Y, Tamaki K, Gamo T. Methane, manganese, and helium-3 in newly discovered hydrothermal plumes over the Central Indian Ridge, 18°-20°S. Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2008;9:n/a.

Levin LA, Baco AR, Bowden DA, Colaco A, Cordes EE, Cunha MR, Demopoulos AWJ, Gobin J, Grupe BM, Le J, et al. Hydrothermal vents and methane seeps: rethinking the sphere of influence. Front Mar Sci. 2016;3.

Hall J. Geology of New York: survey of the fourth geological district. Carol and Cook: Albany; 1843.

Lyell C. Lyell’s travels in North America in the years 1841-1842. NY: C. E. Merrill; 1909.

Macauley J. The natural, statistical and civil history of New York. Gould and Banks: Albany; 1829.

Schimmelmann A, Ensminger SA, Drobniak A, Mastalerz M, Etiope G, Jacobi RD, Frankenberg C. Natural geological seepage of hydrocarbon gas in the Appalachian Basin and Midwest USA in relation to shale tectonic fracturing and past industrial hydrocarbon production. Sci Total Environ. 2018;644:982–93.

Etiope G, Drobniak A, Schimmelmann A. Natural seepage of shale gas and the origin of “eternal flames” in the Northern Appalachian Basin, USA. Mar Pet Geol. 2013;43:178–86.

Reddy CM, Arey JS, Seewald JS, Sylva SP, Lemkau KL, Nelson RK, Carmichael CA, McIntyre CP, Fenwick J, Ventura GT, et al. Composition and fate of gas and oil released to the water column during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:20229–34.

Anthony KMW, Anthony P, Grosse G, Chanton J. Geologic methane seeps along boundaries of Arctic permafrost thaw and melting glaciers. Nat Geosci. 2012;5:419–26.

Wang Q, Chen X, Jha AN, Rogers H. Natural gas from shale formation – the evolution, evidences and challenges of shale gas revolution in United States. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2014;30:1–28.

Jackson RB, Vengosh A, Darrah TH, Warner NR, Down A, Poreda RJ, Osborn SG, Zhao K, Karr JD. Increased stray gas abundance in a subset of drinking water wells near Marcellus shale gas extraction. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11250–5.

Osborn SG, Vengosh A, Warner NR, Jackson RB. Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:8172–6.

Howarth RW, Santoro R, Ingraffea A. Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations. Clim Change. 2011;106:679–90.

Kolb S. The quest for atmospheric methane oxidizers in forest soils. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2009;1:336–46.

Dalal RC, Allen DE. Greenhouse gas fluxes from natural ecosystems. Aust J Bot. 2008;56:369–407.

Dunfield PF. The soil methane sink: In Greenhouse Gas Sinks. Wallingford: CABI; 2007.

DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD, Murrell JC, Gallagher WH, Dennison C, Vuilleumier S. Methanobactin and the link between copper and bacterial methane oxidation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80:387.

Ross MO, Rosenzweig AC. A tale of two methane monooxygenases. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2017;22:307–19.

Chistoserdova L. Modularity of methylotrophy, revisited. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:2603–22.

Trotsenko YA, Murrell JC. Metabolic aspects of aerobic obligate methanotrophy. In Advances in Applied Microbiology. Volume 63. : Academic Press; 2008: 183-229

Picone N, Op den Camp HJM. role of rare earth elements in methanol oxidation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2019;49:39–44.

Semrau JD, DiSpirito AA, Gu W, Yoon S. Metals and methanotrophy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e02289–17.

Chistoserdova L. Lanthanides: new life metals? World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32:138.

Pol A, Barends TR, Dietl A, Khadem AF, Eygensteyn J, Jetten MS, Op den Camp HJ. Rare earth metals are essential for methanotrophic life in volcanic mudpots. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:255–64.

Farhan Ul Haque M, Kalidass B, Bandow N, Turpin EA, DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD. Cerium regulates expression of alternative methanol dehydrogenases in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:7546–52.

Farhan Ul Haque M, Gu W, DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD. Marker exchange mutagenesis of mxaF, encoding the large subunit of the Mxa methanol dehydrogenase, in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;82:1549–55.

Chu F, Lidstrom ME. XoxF acts as the predominant methanol dehydrogenase in the type i methanotroph Methylomicrobium buryatense. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:1317.

Gu W, Farhan Ul Haque M, DiSpirito AA, Semrau JD. Uptake and effect of rare earth elements on gene expression in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016;363.

Akberdin IR, Collins DA, Hamilton R, Oshchepkov DY, Shukla AK, Nicora CD, Nakayasu ES, Adkins JN, Kalyuzhnaya MG. Rare earth elements alter redox balance in Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20ZR. Front Microbiol. 2018;9.

Chu F, Beck DAC, Lidstrom ME. MxaY regulates the lanthanide-mediated methanol dehydrogenase switch in Methylomicrobium buryatense. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2435.

Hibi Y, Asai K, Arafuka H, Hamajima M, Iwama T, Kawai K. Molecular structure of La3+-induced methanol dehydrogenase-like protein in Methylobacterium radiotolerans. J Biosci Bioengineering. 2011;111:547–9.

Nakagawa T, Mitsui R, Tani A, Sasa K, Tashiro S, Iwama T, Hayakawa T, Kawai K. A catalytic role of XoxF1 as La3+-dependent methanol dehydrogenase in Methylobacterium extorquens strain AM1. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50480.

Vu HN, Subuyuj GA, Vijayakumar S, Good NM, Martinez-Gomez NC, Skovran E. Lanthanide-dependent regulation of methanol oxidation systems in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and their contribution to methanol growth. J Bacteriol. 2016;198:1250–9.

Howat AM, Vollmers J, Taubert M, Grob C, Dixon JL, Todd JD, Chen Y, Kaster A-K, Murrell JC. Comparative genomics and mutational analysis reveals a novel XoxF-utilizing methylotroph in the Roseobacter group isolated from the marine environment. Front Microbiol. 2018;9.

Chistoserdova L, Kalyuzhnaya MG. Current trends in methylotrophy. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:703–14.

Dedysh SN, Knief C, Dunfield PF. Methylocella species are facultatively methanotrophic. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4665–70.

Crombie AT, Murrell JC. Trace-gas metabolic versatility of the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris. Nature. 2014;510:148–51.

Tamas I, Smirnova AV, He Z, Dunfield PF. The (d)evolution of methanotrophy in the Beijerinckiaceae-a comparative genomics analysis. ISME J. 2014;8:369–82.

Vorobev A, Jagadevan S, Jain S, Anantharaman K, Dick GJ, Vuilleumier S, Semrau JD. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of the facultative methanotroph Methylocystis sp. strain SB2 grown on methane or ethanol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:3044–52.

Belova SE, Baani M, Suzina NE, Bodelier PLE, Liesack W, Dedysh SN. Acetate utilization as a survival strategy of peat-inhabiting Methylocystis spp. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:36–46.

Semrau JD, DiSpirito AA, Vuilleumier S. Facultative methanotrophy: false leads, true results, and suggestions for future research. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;323:1–12.

Dedysh SN, Dunfield PF: Facultative methane oxidizers. In: McGenity T. (eds) taxonomy, genomics and ecophysiology of hydrocarbon-degrading microbes. Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Springer Cham; 2018.

Chen Y, Crombie A, Rahman MT, Dedysh SN, Liesack W, Stott MB, Alam M, Theisen AR, Murrell JC, Dunfield PF. Complete genome sequence of the aerobic facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3840–1.

Ghashghavi M, Jetten MSM, Luke C. Survey of methanotrophic diversity in various ecosystems by degenerate methane monooxygenase gene primers. AMB Express. 2017;7:162.

Knief C. Diversity and habitat preferences of cultivated and uncultivated aerobic methanotrophic bacteria evaluated based on pmoA as molecular marker. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1346.

Rahman MT, Crombie A, Chen Y, Stralis-Pavese N, Bodrossy L, Meir P, McNamara NP, Murrell JC. Environmental distribution and abundance of the facultative methanotroph Methylocella. ISME J. 2011;5:1061–6.

Farhan Ul Haque M, Crombie AT, Ensminger SA, Baciu C, Murrell JC. Facultative methanotrophs are abundant at terrestrial natural gas seeps. Microbiome. 2018;6:118.

Ashraf W, Mihdhir A, Murrell JC. Bacterial oxidation of propane. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;122:1–6.

Hamamura N, Arp DJ. Isolation and characterization of alkane-utilizing Nocardioides sp. strain CF8. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:21–6.

Kotani T, Kawashima Y, Yurimoto H, Kato N, Sakai Y. Gene structure and regulation of alkane monooxygenases in propane-utilizing Mycobacterium sp. TY-6 and Pseudonocardia sp. TY-7. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;102:184–92.

Sharp JO, Sales CM, LeBlanc JC, Liu J, Wood TK, Eltis LD, Mohn WW, Alvarez-Cohen L. An inducible propane monooxygenase is responsible for N-nitrosodimethylamine degradation by Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:6930–8.

Johnson EL, Hyman MR. Propane and n-butane oxidation by Pseudomonas putida GPo1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:950–2.

Dubbels BL, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Arp DJ. Butane monooxygenase of Pseudomonas butanovora: purification and biochemical characterization of a terminal-alkane hydroxylating diiron monooxygenase. Microbiology. 2007;153:1808–16.

Dubbels BL, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Bottomley PJ, Arp DJ. Thauera butanivorans sp. nov., a C2-C9 alkane-oxidizing bacterium previously referred to as Pseudomonas butanovora. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:1576–8.

Shennan JL. Utilisation of C2–C4 gaseous hydrocarbons and isoprene by microorganisms. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2006;81:237–56.

Cappelletti M, Presentato A, Milazzo G, Turner RJ, Fedi S, Frascari D, Zannoni D. Growth of Rhodococcus sp. strain BCP1 on gaseous n-alkanes: new metabolic insights and transcriptional analysis of two soluble di-iron monooxygenase genes. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:393.

He Y, Mathieu J, Yang Y, Yu P, da Silva MLB, Alvarez PJJ. 1,4-Dioxane biodegradation by Mycobacterium dioxanotrophicus PH-06 is associated with a group-6 soluble di-iron monooxygenase. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2017;4:494–9.

Coleman NV, Bui NB, Holmes AJ. Soluble di-iron monooxygenase gene diversity in soils, sediments and ethene enrichments. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1228–39.

Coleman NV, Yau S, Wilson NL, Nolan LM, Migocki MD, Ly MA, Crossett B, Holmes AJ. Untangling the multiple monooxygenases of Mycobacterium chubuense strain NBB4, a versatile hydrocarbon degrader. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:297–307.

Venturi S, Tassi F, Magi F, Cabassi J, Ricci A, Capecchiacci F, Caponi C, Nisi B, Vaselli O. Carbon isotopic signature of interstitial soil gases reveals the potential role of ecosystems in mitigating geogenic greenhouse gas emissions: case studies from hydrothermal systems in Italy. Sci Total Environ. 2019;655:887–98.

Kietavainen R, Purkamo L. The origin, source, and cycling of methane in deep crystalline rock biosphere. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:725.

Belova SE, Oshkin IY, Glagolev MV, Lapshina ED, Maksyutov SS, Dedysh SN. Methanotrophic bacteria in cold seeps of the floodplains of northern rivers. Microbiology. 2013;82:743–50.

Tavormina PL, Kellermann MY, Antony CP, Tocheva EI, Dalleska NF, Jensen AJ, Valentine DL, Hinrichs K-U, Jensen GJ, Dubilier N, Orphan VJ. Starvation and recovery in the deep-sea methanotroph Methyloprofundus sedimenti. Mol Microbiol. 2017;103:242–52.

Tavormina PL, Hatzenpichler R, McGlynn S, Chadwick G, Dawson KS, Connon SA, Orphan VJ. Methyloprofundus sedimenti gen. nov., sp. nov., an obligate methanotroph from ocean sediment belonging to the ‘deep sea-1’ clade of marine methanotrophs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:251–9.

Rubin-Blum M, Antony CP, Borowski C, Sayavedra L, Pape T, Sahling H, Bohrmann G, Kleiner M, Redmond MC, Valentine DL, Dubilier N. Short-chain alkanes fuel mussel and sponge Cycloclasticus symbionts from deep-sea gas and oil seeps. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17093.

Paul BG, Ding H, Bagby SC, Kellermann MY, Redmond MC, Andersen GL, Valentine DL. Methane-oxidizing bacteria shunt carbon to microbial mats at a marine hydrocarbon seep. Front Microbiol. 2017;8.

Redmond MC, Valentine DL. Natural gas and temperature structured a microbial community response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:20292.

Redmond MC, Valentine DL, Sessions AL. Identification of novel methane-, ethane-, and propane-oxidizing bacteria at marine hydrocarbon seeps by stable isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6412–22.

Reeburgh WS. Oceanic methane biogeochemistry. Chem Rev. 2007;107:486–513.

Crombie A, Murrell JC. Development of a system for genetic manipulation of the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2. In: Rosenzweig AC, Ragsdale SW, editors. Methods in Enzymology, vol. 495. Burlington: Academic Press; 2011. p. 119–33.

Dumont MG, Murrell JC. Stable isotope probing - linking microbial identity to function. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:499–504.

Ho A, Lee HJ, Reumer M, Meima-Franke M, Raaijmakers C, Zweers H, de Boer W, Van der Putten WH, Bodelier PLE. Unexpected role of canonical aerobic methanotrophs in upland agricultural soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2019;131:1–8.

Shiau Y-J, Cai Y, Jia Z, Chen C-L, Chiu C-Y. Phylogenetically distinct methanotrophs modulate methane oxidation in rice paddies across Taiwan. Soil Biol Biochem. 2018;124:59–69.

Jensen S, Neufeld JD, Birkeland N-K, Hovland M, Murrell JC. Methane assimilation and trophic interactions with marine Methylomicrobium in deep-water coral reef sediment off the coast of Norway. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;66:320–30.

Meyer KM, Klein AM, Rodrigues JLM, Nüsslein K, Tringe SG, Mirza BS, Tiedje JM, Bohannan BJM. Conversion of Amazon rainforest to agriculture alters community traits of methane-cycling organisms. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:1547–56.

Putkinen A, Larmola T, Tuomivirta T, Siljanen HMP, Bodrossy L, Tuittila E-S, Fritze H. Peatland succession induces a shift in the community composition of Sphagnum-associated active methanotrophs. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;88:596–611.

Reith F, Rogers SL. Assessment of bacterial communities in auriferous and non-auriferous soils using genetic and functional fingerprinting. Geomicrobiol J. 2008;25:203–15.

Dedysh SN, Derakshani M, Liesack W. Detection and enumeration of methanotrophs in acidic sphagnum peat by 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization, including the use of newly developed oligonucleotide probes for Methylocella palustris. Appl Envir Microbiol. 2001;67:4850–7.

Dedysh SN, Berestovskaya YY, Vasylieva LV, Belova SE, Khmelenina VN, Suzina NE, Trotsenko YA, Liesack W, Zavarzin GA. Methylocella tundrae sp. nov., a novel methanotrophic bacterium from acidic tundra peatlands. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:151–6.

Dunfield PF, Khmelenina VN, Suzina NE, Trotsenko YA, Dedysh SN: Methylocella silvestris sp. nov., a novel methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest cambisol. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:1231-1239.

Dedysh SN, Liesack W, Khmelenina VN, Suzina NE, Trotsenko YA, Semrau JD, Bares AM, Panikov NS, Tiedje JM. Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp. nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bogs, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50(Pt 3):955–69.

Dedysh SN, Panikov NS, Liesack W, Großkopf R, Zhou J, Tiedje JM. Isolation of acidophilic methane-oxidizing bacteria from northern peat wetlands. Science. 1998;282:281–4.

Kallistova A, Montonen L, Jurgens G, Munster U, Kevbrina MV, Nozhevnikova AN. Culturable psychrotolerant methanotrophic bacteria in landfill cover soil. Mikrobiologiia. 2014;83:109–18.

Miller DN, Yavitt JB, Madsen EL, Ghiorse WC. Methanotrophic activity, abundance, and diversity in forested swamp pools: spatiotemporal dynamics and influences on methane fluxes. Geomicrobiol J. 2004;21:257–71.

Radajewski S, Webster G, Reay DS, Morris SA, Ineson P, Nedwell DB, Prosser JI, Murrell JC. Identification of active methylotroph populations in an acidic forest soil by stable-isotope probing. Microbiology. 2002;148:2331–42.

Morris SA, Radajewski S, Willison TW, Murrell JC. identification of the functionally active methanotroph population in a peat soil microcosm by stable-isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1446–53.

Chen Y, Dumont MG, McNamara NP, Chamberlain PM, Bodrossy L, Stralis-Pavese N, Murrell JC. Diversity of the active methanotrophic community in acidic peatlands as assessed by mRNA and SIP-PLFA analyses. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:446–59.

Liebner S, Svenning MM. Environmental transcription of mmoX by methane-oxidizing proteobacteria in a subarctic palsa peatland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:701–6.

Han B, Chen Y, Abell G, Jiang H, Bodrossy L, Zhao J, Murrell JC, Xing X-H. Diversity and activity of methanotrophs in alkaline soil from a Chinese coal mine. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;70:196–207.

Smirnova A, Dunfield P. Differential transcriptional activation of genes encoding soluble methane monooxygenase in a facultative versus an obligate methanotroph. Microorganisms. 2018;6:20.

Mardina P, Li J, Patel SK, Kim IW, Lee JK, Selvaraj C. Potential of immobilized whole-cell Methylocella tundrae as a biocatalyst for methanol production from methane. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26:1234–41.

Wang J, Geng K, Farhan Ul Haque M, Crombie A, Street L, Wookey P, Ma K, Murrell JC, Pratscher J. Draft genome sequence of Methylocella silvestris TVC, a facultative methanotroph isolated from permafrost. Genome Announc. 2018;6:e00040–18.

Kox MAR, Farhan Ul Haque M, van Alen TA, Crombie AT, Jetten MSM, Op den Camp HJM, Dedysh SN, van Kessel MAHJ, Murrell JC. Complete genome sequence of the aerobic facultative methanotroph Methylocella tundrae strain T4. Microbiol Res Announc. 2019;8:e00286–019.

Vekeman B, Kerckhof FM, Cremers G, de Vos P, Vandamme P, Boon N, Op den Camp HJM, Heylen K. New Methyloceanibacter diversity from North Sea sediments includes methanotroph containing solely the soluble methane monooxygenase. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:4523–36.

Dedysh SN, Naumoff DG, Vorobev AV, Kyrpides N, Woyke T, Shapiro N, Crombie AT, Murrell JC, Kalyuzhnaya MG, Smirnova AV, Dunfield PF. Draft genome sequence of Methyloferula stellata AR4, an obligate methanotroph possessing only a soluble methane monooxygenase. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e01555–14.

Keltjens JT, Pol A, Reimann J, Op den Camp HJM. PQQ-dependent methanol dehydrogenases: rare-earth elements make a difference. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:6163–83.

Vekeman B, Speth D, Wille J, Cremers G, De Vos P, Op den Camp HJ, Heylen K. Genome characteristics of two novel type i methanotrophs enriched from North Sea sediments containing exclusively a lanthanide-dependent XoxF5-type methanol dehydrogenase. Microb Ecol. 2016;72:503–9.

Chistoserdova L, Chen S-W, Lapidus A, Lidstrom ME. Methylotrophy in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 from a genomic point of view. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2980–7.

Sluis MK, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Arp DJ. Molecular analysis of the soluble butane monooxygenase from ‘Pseudomonas butanovora’. Microbiology. 2002;148:3617–29.

Bottomley PJ, Arp DJ, Sayavedra-Soto LA. Involvement of BmoR and BmoG in n-alkane metabolism in ‘Pseudomonas butanovora’. Microbiology. 2008;154:139–47.

Kalyuzhnaya MG, Gomez OA, Murrell JC. The methane-oxidizing bacteria (methanotrophs). In Taxonomy, genomics and ecophysiology of hydrocarbon-degrading microbes. Edited by McGenity TJ. Cham: Springer Nature; 2019. p. 1-34.

Crombie AT, Larke-Mejia NL, Emery H, Dawson R, Pratscher J, Murphy GP, McGenity TJ, Murrell JC. Poplar phyllosphere harbors disparate isoprene-degrading bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:13081.

Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T, Peplies J, Quast C, Horn M, Glöckner FO. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e1.

Eren AM, Zozaya M, Taylor CM, Dowd SE, Martin DH, Ferris MJ. Exploring the diversity of Gardnerella vaginalis in the genitourinary tract microbiota of monogamous couples through subtle nucleotide variation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26732.

Dowd SE, Sun Y, Wolcott RD, Domingo A, Carroll JA. Bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP) for microbiome studies: bacterial diversity in the ileum of newly weaned Salmonella-infected pigs. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2008;5:459–72.

Dowd SE, Callaway TR, Wolcott RD, Sun Y, McKeehan T, Hagevoort RG, Edrington TS. Evaluation of the bacterial diversity in the feces of cattle using 16S rDNA bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP). BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:125.

Capone KA, Dowd SE, Stamatas GN, Nikolovski J. Diversity of the human skin microbiome early in life. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2026–32.

Swanson KS, Dowd SE, Suchodolski JS, Middelbos IS, Vester BM, Barry KA, Nelson KE, Torralba M, Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, et al. Phylogenetic and gene-centric metagenomics of the canine intestinal microbiome reveals similarities with humans and mice. ISME J. 2011;5:639–49.

Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2010;26:2460–1.

Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–55.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9.

Medigue C, Calteau A, Cruveiller S, Gachet M, Gautreau G, Josso A, Lajus A, Langlois J, Pereira H, Planel R, et al. MicroScope-an integrated resource for community expertise of gene functions and comparative analysis of microbial genomic and metabolic data. Briefings Bioinf. 2017.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Calin Baciu for the Andreiasu Everlasting Fire (Romania) samples and Scott A Ensminger, William Baker, Jerry Baker, Doug Confer, and Bob Confer for facilitating sampling of Pipe Creek (New York, USA) gas seeps.

Funding

Work on this project was supported by the Leverhulme Trust Research project (grant number RPG2016-050) to JCM and Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship (grant number ECF-2016-626) to ATC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MFUH, ATC and JCM planned the experiments. MFUH carried out experimental work and analysed the data. MFUH, ATC and JCM wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Growth of Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 under various substrates. Table S2. In-silico DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) of Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 genomes compared with other Methylocella strains. Table S3. Genes identified putatively involved in the central metabolism of C-1 substrates in Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4. Table S4. Primers used for PCR amplification in this study. Table S5. Characteristics of sequenced genomes of new Methylocella isolates. Figure S1. Relative abundance (%) of dominant bacterial phyla as revealed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing of DNA from native environmental samples. Figure S2. DNA retrieved as a function of refractive index of each fraction recovered after ultracentrifugation. Figure S3. Growth curves of Methylocella sp. PC1 and PC4 under various gaseous substrates. Figure S4. Phylogenetic analysis of methanol dehydrogenases from Methylocella PC1 and PC4 isolates. (PDF 798 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Farhan Ul Haque, M., Crombie, A.T. & Murrell, J.C. Novel facultative Methylocella strains are active methane consumers at terrestrial natural gas seeps. Microbiome 7, 134 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0741-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0741-3