Abstract

Background

Early-weaning of piglets is often accompanied by severe disorders, especially diarrhea. The gut microbiota and its metabolites play a critical role in the maintenance of the physiologic and metabolic homeostasis of the host. Our previous studies have demonstrated that oral administration of Lactobacillus frumenti improves epithelial barrier functions and confers diarrhea resistance in early-weaned piglets. However, the metabolic response to L. frumenti administration remains unclear. Then, we conducted simultaneous serum and hepatic metabolomic analyses in early-weaned piglets administered by L. frumenti or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Results

A total of 100 6-day-old crossbred piglets (Landrace × Yorkshire) were randomly divided into two groups and piglets received PBS (sterile, 2 mL) or L. frumenti (suspension in PBS, 108 CFU/mL, 2 mL) by oral administration once per day from 6 to 20 days of age. Piglets were weaned at 21 days of age. Serum and liver samples for metabolomic analyses were collected at 26 days of age. Principal components analysis (PCA) showed that L. frumenti altered metabolism in serum and liver. Numerous correlations (P < 0.05) were identified among the serum and liver metabolites that were affected by L. frumenti. Concentrations of guanosine monophosphate (GMP), inosine monophosphate (IMP), and uric acid were higher in serum of L. frumenti administration piglets. Pathway analysis indicated that L. frumenti regulated fatty acid and amino acid metabolism in serum and liver. Concentrations of fatty acid β-oxidation related metabolites in serum (such as 3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine, C4-OH) and liver (such as acetylcarnitine) were increased after L. frumenti administration.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that L. frumenti regulates lipid metabolism and amino acid metabolism in the liver of early-weaned piglets, where it promotes fatty acid β-oxidation and energy production. High serum concentrations of nucleotide intermediates, which may be an alternative strategy to reduce the incidence of diarrhea in early-weaned piglets, were further detected. These findings broaden our understanding of the relationships between the gut microbiota and nutrient metabolism in the early-weaned piglets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the modern intensive swine industry, early weaning strategy can enhance the whole growth performance, but this process also involves complex psychologic, immunologic, environmental, and nutritional stresses [1, 2]. Diarrhea is a major challenge for early-weaned piglets which led to gut microbial dysbiosis, intestinal damage and inflammation, body weight loss, and potentially death [1,2,3]. The antibiotics overuse and the consequent drug resistance raises serious concerns about both animal and public health. To prevent this problem worsening, the identification or development of alternatives to the established antibiotics for use in early-weaned pigs represents an urgent challenge [2].

Non-antimicrobial alternatives, such as probiotics [4], prebiotics [5], and essential oils [6], have the ability to diminish weaning-associated challenges, especially post-weaning diarrhea. Importantly, probiotics confer a health benefit to the host. Probiotics have been shown to be effective in growth promotion, high feed utilization efficiency, improvement of gastrointestinal conditions, activation of the immune system, restoration of gut microbial balance, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders [7]. These effects imply that probiotics may be useful in the management of the weaning phase in pigs as alternatives to antibiotics.

The effects of probiotics in weaned piglets have been widely documented, such as protection of piglets from post-weaning infections, maintenance of intestinal epithelial barrier function and stimulation of the piglets immune system [1]. Lactic acid-producing bacteria [2], such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, Enterococcus, or Streptococcus and Saccharomyces, are the most commonly used microorganisms. Several recent studies have shown that the administration of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp. restores the gut microbiota and health [8,9,10,11]. Despite the fact that the underlying mechanisms of these effects are not well understood, the prevention of post-weaning disorders in piglets using probiotics could be the result of the inhibition of pathogen adhesion to the intestinal mucosa and their growth, improvement of intestinal epithelial barrier functions, or modifications in the diversity or composition of the gut microbiota.

Our previous study has found that L. frumenti significantly increased the body weights [12] and significantly decreased the diarrhea incidence of the early-weaned piglets [13]. These studies have shown that L. frumenti improves the intestinal epithelial barrier function and confers diarrhea resistance to early-weaned piglets. However, the effects of L. frumenti administration on whole-body metabolism have not been well-characterized. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effects of L. frumenti on the serum and liver metabolomic profiles of early-weaned piglets. To this end, metabolomics, using a mass spectrometry-based technique, was employed to identify the metabolic differences in early-weaned piglets administered with L. frumenti or PBS in this study.

Methods

Animals and sample collection

The bacterial strain Lactobacillus frumenti was isolated from the feces of piglets, as previously described [13]. All animal experimental procedures (permit number: HZAUSW2013–0006) were performed using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University. A total of 100 crossbred piglets (Landrace × Yorkshire) of similar birth weight from 15 litters were randomly allocated to two groups (group A, PBS and group B, L. frumenti). Each group was then randomly assigned to five pens, which pen size is one sow with a litter size of 10 (five males and five females). At 6 days of age, male piglets were castrated. Piglets in group A were treated daily with 2 mL sterile PBS by oral gavage from age of 6–20 days. Piglets in group B were treated daily with 2 mL L. frumenti suspension in PBS (108CFU/mL) by oral administration from age of 6–20 days. The piglets were then weaned at 21 days of age. All the piglets had free access to diet and water. The diet compositions for early-weaned piglets was as previously described [12]. At 26 days of age, one male piglet was randomly selected from each pen and slaughtered 12 h after the last meal. The blood sample was collected and serum was separated by centrifugation at 1500×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The liver sample was washed twice with PBS and then rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The serum and liver samples were stored at − 80 °C until further analysis.

Metabolomic profiling

Liver samples were ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and serum samples were thawed on ice before metabolite extraction. Firstly, 100 mg liver powder or 100 μL serum sample were mixed with 400 μL methanol for 60 min at − 20 °C to precipitate proteins, and the extracts were harvested by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were transferred to new vials, and aliquots were taken and dried under nitrogen and then under vacuum overnight. Aliquots from each sample were reconstituted in solvent mixtures and shaken for 5 min, prior to centrifugation at 14,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. Prior to liquid chromatography (LC)-mass spectrometry (MS)/MS analysis, an aliquot from each sample was pooled to create quality control (QC) samples that were used to evaluate the internal standards and instrument performance.

The samples were analyzed using a Thermo Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer connected to a Thermo Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Scientific, USA). The UltiMate 3000 HPLC system was equipped with a hydrophobic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) column. The HILIC column was a Thermo Accucore HILIC column (100 × 3 mm, internal diameter 2.6 μm, part number: 17526-10330). The column was warmed to 40 °C before use. The HILIC column was used as follows: mobile phase A was 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate and mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The gradient was: 0–1 min, 5% B; 1–2 min, a linear gradient from 5% B to 40% B; 2–11 min, a linear gradient from 40% B to 80% B; 11–15 min, 95% B. The electrospray ionization source on the Q Exactive HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer was set as follows: the spray voltage was set to 3.8 kV in ES+ and 3.2 kV in ES−; the flow rates of the sheath gas and aux gas were 35 arb and 10 arb, respectively; and the capillary temperature was 350 °C.

Validation of the important metabolites

Nucleotides and fatty acid oxidation metabolites in this manuscript were confirmed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography [14] and amino acids and DL-lactic acid were confirmed as described previously [15].

Data processing

An untargeted metabolomic workflow with identification using mzCloud (ddMS2), ChemSpider (formula or exact mass), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways was used for the processing of the raw data. All the raw files generated in the QE HF-X analysis were processed using Compound Discoverer 2.0 software (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Blank injections were used to remove background ion peaks. Quantification data were normalized to the output from QC samples, and the metabolites that were present at significantly different concentrations between the groups were identified using a variable influence on projection (VIP) of > 1 and a P value of t-tests statistics < 0.05 based on the peak intensities.

Correlation analysis

To identify significant temporal correlations among metabolites in each tissue, we applied a robust permutation test, which performed 1000 random permutations of the replicate samples, and estimated the Pearson correlation coefficients and significance levels. Correlations between metabolites with P values < 0.05 in 95% (99% within tissue Circos plots) of all permutation tests were considered to be significant. Calculations were performed using the R package 3.5.1.

Western blotting

Liver samples were lysed using lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin, and 50 μg/mL polymethyl sulfonyl fluoride). Equal amounts of tissue lysate were resolved using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (16916600, Roche), blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature, and probed with primary antibodies against acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (ACOX1) (AB091), long-chain fatty acid CoA ligase 1 (ACSL1) (A1000), short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACADS) (A0945), carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1) (A5307), and β-actin (A026) (all from ABclonal Technology). The specific proteins were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (sc-2004, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), developed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (34,080, Thermo Scientific), and visualized using a Kodak Image Station 2000 MM. Immunoblotting results were quantified using Image J software (1.49 s). All the immunoblotting assays were performed using three biologic replicates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the western blotting data was performed using GraphPad Prism software (6.0c). All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Metabolomic profiling of serum and liver from early-weaned piglets orally administered L. frumenti

The PBS and L. frumenti-treated groups could be readily differentiated using their metabolite fingerprints, with excellent separation of the PBS and L. frumenti-treated early-weaned piglets being achieved using the first two components of a principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig.1a and b). The metabolomic analysis permitted the identification and quantification of 2074 metabolites in both serum and liver (Fig. 1c and d), of which 100 were present at concentrations that differed between the groups in the serum and 113 in the liver (fold change > 1.5, or fold change < 0.67). These profiles are displayed as heat maps (Fig. 1e and f). piglets. DL-Lactic acid, a product of fermentation by Lactobacilli, is upregulated in both serum and liver (Fig. 1g and h). And the body weights of early-weaned piglets were significantly increased by oral administration of L. frumenti (Fig. 1i). These data indicate that oral administration of L. frumenti significantly modulates the metabolism of early-weaned piglets.

Serum and liver metabolic profiles of piglets orally treated with L. frumenti or PBS. a, b Principal components analysis of serum and liver metabolites in early-weaned piglets gavaged with PBS or L. frumenti. c, d Volcano plot summarizing the distribution of the metabolites. Red, green, and gray dots represent metabolites with higher, lower, or similar abundance, respectively. e, f Heat map of the metabolites present at differing concentrations in serum and liver of the treated and control early-weaned piglets. g, h Representative variation of L. frumenti metabolism in serum and liver. LF, L. frumenti. i The body weights of early-weaned piglets used in metabolomic study. All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.001 (***). n = 5 piglets

Correlations in metabolite concentrations within tissues reveal specific differences in metabolism

Numerous positive and negative correlations among the metabolites in the serum and liver were identified (Fig. 2a and b). Interestingly, opposing effects of L. frumenti administration on metabolite correlations in the serum and liver were observed (Fig. 2c). Serum gained 21.8% correlations on L. frumenti, whereas liver lost 15.1% correlations on L. frumenti, indicating maintenance and/or reorganization of metabolism in blood and liver.

Correlations between serum and liver metabolites that were altered by L. frumenti administration. a, b Correlation heat maps for the metabolites in each tissue. The correlation coefficient (rho) is shown in red (positive) or blue (negative) (LF, L. frumenti). c Number of significantly different metabolite correlations between the L. frumenti and PBS groups. d, e Graphical representation of the significant metabolite correlations. Each ribbon indicates a significant correlation between or within each metabolite class and the ribbon thickness represents the number of significantly correlated metabolites. The metabolites were ordered according to metabolite class, as indicated by the colored bar around the circumference

To further characterize the correlations among the metabolites, the significant positive and negative correlations were classified according to metabolite class (Fig. 2d and e). Comparative analysis of intra-tissue metabolite correlations showed that unclassified compounds and xenobiotics had the strongest correlations with other metabolites in the serum and liver, respectively. Notably, there were more correlations between serum amino acids and other metabolites in the L. frumenti group, whereas there were slightly fewer in the liver. These differences in the correlations among the metabolites between the groups imply that metabolism is differentially organized in the two groups of piglets.

L. frumenti induces differences in lipid and amino acid metabolism in early-weaned piglets

In serum, the enriched pathways were mainly linked to circulating fatty acid metabolism and amino acid metabolism, especially the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 3a). Pathway enrichment analysis showed that specific lipid classes were present at significantly different concentrations in the liver of L. frumenti-administration piglets, including those indicative of differences in alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, and fatty acid biosynthesis (Fig. 3b), such as long-chain fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), phospholipids, and lysolipids. Metabolites implicated in amino acid metabolism, particularly in alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, and cysteine and methionine metabolism, were also highly affected by L. frumenti.

Metabolites significantly associated with L. frumenti administration

To visualize the metabolites altered by L. frumenti administration, hierarchical clustering was used to categorize them on the basis of their differences in concentration. Among the altered metabolites, 59 metabolites were present at a higher concentration and 41 metabolites at a lower concentration in L. frumenti-treated piglet serum (Fig. 4a). Specific lipid classes were affected by L. frumenti, including long-chain fatty acids, poly-unsaturated fatty acids, phospholipids, and triacylglycerols. In the liver of the piglets, 55 metabolites were present at higher concentrations and 58 metabolites at lower concentrations (Fig. 4b). The concentrations of several amino acids and peptides were higher, whereas that of 3-oxo-hexadecanoic acid, an intermediate in fatty acid biosynthesis, was lower. Differences in the concentrations of long-chain fatty acids and poly-unsaturated fatty acids were also identified. Notably, 14 metabolites showed differences in concentrations in both the serum and liver (Fig. 4c), and Z scores were calculated to demonstrate these differences (Fig. 4d).

Metabolites significantly associated with L. frumenti administration. a, b Heat map of serum and liver metabolites affected by L. frumenti administration (LF, L. frumenti). c Metabolites affected in both serum and liver. d Relative amounts of similarly affected metabolites in serum and liver, transformed into Z scores in the heat map

L. frumenti administration affects nucleotide metabolism

The serum metabolomics also showed that GMP, IMP, and their metabolite uric acid were present at higher concentrations (Fig. 5a), indicating that L. frumenti may influence purine nucleotide metabolism in early-weaned piglets. Additionally, we found that uridine monophosphate (UMP) was also present at higher concentrations (Fig. 5b), while uracil (Fig. 5c) and cytosine (Fig. 5d) were present at lower concentrations. Another striking effect of L. frumenti on nucleotides was reflected in the presence of thymine and its precursor dihydrothymine at higher concentrations in treated piglets (Fig. 5e). The metabolic pathways of the nucleotides are summarized in Fig. 5f. In sum, our data suggest that L. frumenti promotes nucleotide catabolism in early-weaned piglets.

Regulation of nucleotide metabolism by L. frumenti in early-weaned piglets. a Purine nucleotide abundances in serum (LF, L. frumenti). b, c Uracil-related metabolite abundances in serum. d, e Cytosine and thymine-related metabolite abundances in serum. f Scheme showing how the metabolites of purine are interrelated and affected by L. frumenti administration. Metabolites significantly increased by L. frumenti are indicated by red text, while significantly reduced metabolites are green. Black metabolites were not measured. GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; UMP, uridine monophosphate. All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**). n = 5 piglets

L. frumenti administration promotes fatty acid oxidation and energy production in the liver of early-weaned piglets

Interestingly, previous studies have found that purine nucleotides are involved in energy conservation in the mitochondria of brown adipose tissue [16]. Therefore, we speculated that L. frumenti may regulate energy metabolism in early-weaned piglets. L-acetylcarnitine, which facilitates the movement of acetyl-CoA into mitochondria during the oxidation of fatty acids, was present at higher concentrations in the liver (Fig. 6a). Fatty acid β-oxidation metabolites, such as C4-OH, were also present at higher concentrations in serum of L. frumenti administration piglets (Fig. 6b). Dicarboxylate adipic acid and suberic acid, which are formed by peroxisomal β-oxidation, were present at higher concentrations in the liver of L. frumenti administration piglets (Fig. 6c), and we therefore speculated that the hepatic oxidation of fatty acids may be activated following L. frumenti administration. To test this possibility, the expression of key enzymes (ACADS, ACSL1, ACOX1, ACOT4 and CPT1) involved in fatty acid β-oxidation was measured (Fig. 6d-i). These five enzymes were significantly upregulated by L. frumenti administration. ACSL1 and CPT1 were significantly upregulated by L. frumenti administration. In addition, the protein ACOX1 and ACOT4 were upregulated. These results suggest that L. frumenti administration activates fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver of early-weaned piglets.

L. frumenti administration upregulates fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver of early-weaned piglets. a–c Fatty acid β-oxidation metabolites. d Metabolic enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation. e–i Quantification of the proteins in (d). All values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**),P < 0.001 (***), and P < 0.0001 (***). n = 5 piglets

Discussion

It is now widely accepted that gut microbial dysbiosis, induced by adverse dietary and environmental changes, is a key component of the etiology of post-weaning diarrhea and enteric infections. Studies conducted in recent years have identified the gut microbiota as a critical factor in gut health and metabolic homeostasis in early-weaned piglets [3]. Lactobacilli become established early in the intestine of piglets, and remain as one of the predominant bacterial communities throughout the lifetime of the pigs [17, 18], indicating that Lactobacillus may be a major factor in disease prevention and production performance [19, 20]. Our previous studies also indicated that oral administration of L. frumenti significantly increased the relative abundances of L. frumenti in early-weaned piglet fecals [12, 13]. In this study we found that oral administration of L. frumenti increased DL-lactic acid in serum and liver, suggesting that the administered L. frumenti may successfully colonize the gut. In accordance with our previous study [12], we observed that body weight was increased by oral administration of L. frumenti, indicating that L. frumenti may play an important role in early-weaned piglets. Growing evidence suggests that the gut microbiota regulate host energy metabolism. Our previous study demonstrated that Lactobacillus gasseri LA39 may act as a potential probiotic and stimulates energy production in early-weaned piglets [21]. The present study provides new insights into the effects of L. frumenti to increase the β-oxidation of fatty acid in the liver of early-weaned piglets.

In order to visualization of the correlations of intra-tissue metabolites altered by L. frumenti, we carried out correlation analysis. The results indicated clear differences between serum and liver. Increased correlations in serum may indicate that L. frumenti increased blood cycle and promote the metabolism in whole body, underscoring the role of L. frumenti in metabolic regulation. By contrast, the loss of correlations in liver implicates the reorganization of metabolism and may enhance liver functions. Interestingly, this observation may be the result of differences in the concentrations of unclassified compounds and xenobiotics, which are mainly absorbed from the gut and reach the liver through the hepatic portal vein.

Our data provide a resource to map the metabolic changes induced by L. frumenti gavage. L. frumenti-fed early-weaned piglets displayed significantly different serum and liver metabolic profiles from PBS-fed piglets, suggesting that L. frumenti affects whole-body metabolic regulation. Previous studies have shown that the gut microbiota can exert a substantial influence on host lipid metabolism [22, 23] and amino acid metabolism [24, 25]. Early weaning stress impairs development of mucosal barrier function in the porcine intestine, while our previous studies have proved that L. frumenti contributes to improve the intestinal epithelial barrier functions in early-weaned piglets [12]. Under these conditions, the liver may uptake more nutrients absorbed from the intestine and energy metabolism in the liver increases to metabolize these nutrients. The liver is a major site of fatty acid oxidation in animals [26]. Key enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation,such as ACSL1, CPT1, ACOX1 and ACOT4, were upregulated in the liver of the early-weaned piglets with L. frumenti oral adminidtration. Our data indicated that L frumenti activated fatty acid β-oxidation to increase energy production in the liver of early-weaned piglets.

In addition to β-oxidation byproducts, others metabolites that are involved in the tricarboxylic (TCA) cycle were also identified at different concentrations between PBS treatment and LF treatment (Fig. 7). Succinic acid is a vital intermediate in the TCA cycle, and in the present study serum succinic acid was present at significantly higher concentrations in L. frumenti-treated piglets. Furthermore, 4-hydroxybutyric acid can also be converted to succinic acid in liver [27]. Propionic acid is mainly derived from fermentation in the colon [28], and our data shows that L. frumenti maybe involved in upregulating fermentation in the colon, given the higher concentration of serum propionic acid detected. Propionic acid can be converted to propionyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle [29]. The lower concentration of propionic acid in the liver may indicate that propionic acid is utilized at a high rate in early-weaned piglets.

Suckling piglets have a special requirement for nucleotides, such as cytidine 5′-monophosphate (CMP), adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP), GMP, UMP, and IMP [30]. These nucleotides are involved in growth and maintenance, development, inflammation, and stress, and nucleotide demand increases during weaning. Significantly, restoration of intestinal mucosal integrity was observed in studies of nucleotide supplementation of weaning rats with diarrhea [31, 32]. Moreover, nucleotides cause diarrhea resistance in early-weaned piglets [33,34,35]. In addition, nucleotides, as energy donors and intermediates in biosynthetic and oxidative pathways, are involved in many cellular metabolic processes. Finally, dietary nucleotides are beneficial for ileal mitochondrial function in weaning rats with chronic diarrhea [36] and they have been reported to promote the growth and enzymatic maturation of the small intestine [37]. In the present study, increases in nucleotide concentrations induced by L. frumenti administration may have similar effects to direct nucleotide supplementation, with beneficial effects in early-weaned piglets, such as diarrhea resistance and improved intestinal epithelial barrier function, as observed previously [12]. IMP is produced by de novo synthesis and serves as a precursor for the formation of other nucleotides, such as GMP [38]. Moreover, nucleotides have also been shown to increase plasma immunoglobulin A (IgA) concentrations in early-weaned piglets [35], and this was consistent with our previous findings [12]. And we speculated that increased UMP or nucleotides maybe synthesized in gut by L. frumenti. While uracil decreases in serum, an increase expected, we hypothesis uracil maybe degrade to urea or used in β-alanine metabolism. Taken together, these results suggest that L. frumenti administration may benefit early-weaned piglets by increasing nucleotide concentrations.

The gut microbiota also regulates glutathione (GSH) and amino acid metabolism in the host [39]. Our KEGG analysis shows that L. frumenti regulates amino acid metabolism and glutathione metabolism in the liver of early-weaned piglets. GSH plays a key role in reducing oxidative stress, and most GSH synthesis occurs in the liver from cysteine, glutamate (Glu), and glycine (Gly) [40]. While lower hepatic Cys content may limit GSH production, an increase in hepatic Glu content may enhance the uptake of Cys from the blood via the cysteine-glutamate antiporter, resulting in a higher intracellular concentration of GSH. Fatty acid β-oxidation supplys energy for GSH synthesis. Amino acids also provide TCA cycle substrates. A previous study showed that serum glutamine (Gln) enters the TCA cycle to generate ATP in the liver of early-weaned piglets [41], after conversion to Glu and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) [42].

Glu, Gln, and Gly are all essential precursors of proteins and nucleotides [43, 44], and a growing number of studies suggests that amino acids are important for the maintenance of gut development and health [45]. In the present study, L. frumenti administration was associated with higher concentrations of Glu, Gln, Gly, and Cys, which may all be involved in the maintenance of gut health and development in the early-weaned piglets [46,47,48]. By contrast, the lower serum concentrations of leucine (Leu) and proline (Pro) indicate that L. frumenti may result from protein synthesis in skeletal muscle, leading to an increase in amino acid absorption from the circulation. These results suggest that L. frumenti promotes gut health through amino acid regulation.

Conclusions

In sum, oral administration of L. frumenti in early-weaned piglets affects metabolic homeostasis, especially lipid metabolism and amino acid metabolism, and induces fatty acid β-oxidation and amino acid use for energy production in the liver. L. frumenti administration also increases nucleotide concentrations, which may contribute to diarrhea resistance. In addition, L. frumenti may protect early-weaned piglets from oxidative stress by promoting GSH synthesis in the liver. These findings further highlight the importance of the gut microbiota for diarrhea resistance and demonstrate an effect of L. frumenti to promote energy production in early-weaned piglets.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated or analyzed during this study are presented in this manuscript and available to readers.

Abbreviations

- ACOT4:

-

Acyl-CoA thioesterase 4

- ACOX1:

-

Acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1

- ACSL1:

-

Long-chain fatty acid CoA ligase 1

- C4-OH:

-

3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine

- CPT1:

-

Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1

- GMP:

-

Guanosine monophosphate

- IMP:

-

Inosine monophosphate

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- UMP:

-

Uridine monophosphate

References

Lalles JP, Bosi P, Smidt H, Stokes CR. Weaning - A challenge to gut physiologists. Livest Sci. 2007;108:82–93.

Campbell JM, Crenshaw JD, Polo J. The biological stress of early weaned piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2013;4:19.

Gresse R, Chaucheyras-Durand F, Fleury MA, Van de Wiele T, Forano E, Blanquet-Diot S. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in postweaning piglets: understanding the keys to health. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:851–73.

Xu JQ, Li YH, Yang ZQ, Li CH, Liang HY, Wu ZW, et al. Yeast probiotics shape the gut microbiome and improve the health of early-weaned piglets. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2011.

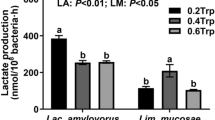

Konstantinov SR, Awati A, Smidt H, Williams BA, Akkermans AD, de Vos WM. Specific response of a novel and abundant Lactobacillus amylovorus-like phylotype to dietary prebiotics in the guts of weaning piglets. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3821–30.

Zeng ZK, Xu X, Zhang Q, Li P, Zhao PF, Li QY, et al. Effects of essential oil supplementation of a low-energy diet on performance, intestinal morphology and microflora, immune properties and antioxidant activities in weaned pigs. Anim Sci J. 2015;86:279–85.

Heo JM, Opapeju FO, Pluske JR, Kim JC, Hampson DJ, Nyachoti CM. Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: a review of feeding strategies to control post-weaning diarrhoea without using in-feed antimicrobial compounds. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl), 2013. 97:207–37.

Chiang ML, Chen HC, Chen KN, Lin YC, Lin YT, Chen MJ. Optimizing production of two potential probiotic Lactobacilli strains isolated from piglet feces as feed additives for weaned piglets. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2015;28:1163–70.

Hu YL, Dun YH, Li SA, Zhang DX, Peng N, Zhao SM, et al. Dietary Enterococcus faecalis LAB31 improves growth performance, reduces diarrhea, and increases fecal Lactobacillus number of weaned piglets. PLoS One. 2015;10:e011663.

Barszcz M, Taciak M, Skomiał J. The effects of inulin, dried Jerusalem artichoke tuber and a multispecies probiotic preparation on microbiota ecology and immune status of the large intestine in young pigs. Arch Anim Nutr. 2016;70:278–92.

Dowarah R, Verma A, Agarwal N, Patel B, Singh P. Effect of swine based probiotic on performance, diarrhoea scores, intestinal microbiota and gut health of grower-finisher crossbred pigs. Livest Sci. 2017;195:74–9.

Hu J, Chen LL, Zheng WY, Shi M, Liu L, Xie CL, et al. Lactobacillus frumenti facilitates intestinal epithelial barrier function maintenance in early-weaned piglets. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:897.

Hu J, Ma LB, Nie YF, Chen JW, Zheng WY, Wang XK, et al. A microbiota-derived bacteriocin targets the host to confer diarrhea resistance in early-weaned piglets. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:817–32.

Taylor M, Hershey H, Levine R, Coy K, Olivelle S. Improved method of resolving nucleotides by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 1981;219(1):133–9.

Mau J-L, Chyau C-C, Li J-Y, Tseng Y-H. Flavor compounds in straw mushrooms Volvariella volvacea harvested at different stages of maturity. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45(12):4726–9.

den Besten G, Lange K, Havinga R, van Dijk TH, Gerding A, van Eunen K, et al. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids are vividly assimilated into host carbohydrates and lipids. Am J Physiol-Gastr L. 2013;305:G900–10.

Naito S, Hayashidani H, Kaneko K, Ogawa M, Benno Y. Development of intestinal Lactobacilli in normal piglets. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:230–6.

de Angelis M, Siragusa S, Berloco M, Caputo L, Settanni L, Alfonsi G, et al. Selection of potential probiotic lactobacilli from pig feces to be used as additives in pelleted feeding. Res Microbiol. 2006;157:792–801.

van Baarlen P, Wells JM, Kleerebezem M. Regulation of intestinal homeostasis and immunity with probiotic lactobacilli. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:208–15.

Konstantinov SR, Awati AA, Williams BA, Miller BG, Jones P, Stokes CR, et al. Post-natal development of the porcine microbiota composition and activities. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1191–9.

Hu J, Ma LB, Zheng WY, Nie YF, Yan XH. Lactobacillus gasseri LA39 activates the oxidative phosphorylation pathway in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3025.

Rabot S, Membrez M, Bruneau A, Gerard P, Harach T, Moser M, et al. Germ-free C57BL/6J mice are resistant to high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and have altered cholesterol metabolism. FASEB J. 2010;24:4948–59.

Velagapudi VR, Hezaveh R, Reigstad CS, Gopalacharyulu P, Yetukuri L, Islam S, et al. The gut microbiota modulates host energy and lipid metabolism in mice. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1101–12.

Neis EP, Dejong CH, Rensen SS. The role of microbial amino acid metabolism in host metabolism. Nutrients. 2015;7:2930–46.

Lin R, Liu WT, Piao MY, Zhu H. A review of the relationship between the gut microbiota and amino acid metabolism. Amino Acids. 2017;49:2083–90.

Bergen WG, Mersmann HJ. Comparative aspects of lipid metabolism: impact on contemporary research and use of animal models. J Nutr. 2005;135:2499–502.

Gibson KM, Nyhan WL. Metabolism of [U-14C]-4-hydroxybutyric acid to intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid cycle in extracts of rat liver and kidney mitochondria. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1989;14:61–70.

Cummings J, Pomare E, Branch W, Naylor C, Macfarlane GT. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28:1221–7.

Al-Lahham SH, Peppelenbosch MP, Roelofsen H, Vonk RJ, Venema K. Biological effects of propionic acid in humans; metabolism, potential applications and underlying mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1801;2010:1175–83.

Mateo CD, Peters DN, Stein HH. Nucleotides in sow colostrum and milk at different stages of lactation. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1339–42.

Nunez MC, Ayudarte MV, Morales D, Suarez MD, Gil A. Effect of dietary nucleotides on intestinal repair in rats with experimental chronic diarrhea. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1990;14:598–604.

Bueno J, Torres M, Almendros A, Carmona R, Nunez MC, Rios A, et al. Effect of dietary nucleotides on small intestinal repair after diarrhoea. Histological and ultrastructural changes. Gut. 1994;35:926–33.

Lee DN, Liu SR, Chen YT, Wang RC, Lin SY, Weng CF. Effects of diets supplemented with organic acids and nucleotides on growth, immune responses and digestive tract development in weaned pigs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2007;91:508–18.

Martinez-Puig D, Manzanilla EG, Morales J, Borda E, Perez JF, Pineiro C, et al. Dietary nucleotide supplementation reduces occurrence of diarrhoea in early weaned pigs. Livest Sci. 2007;108:276–9.

Sauer N, Eklund M, Bauer E, Ganzle MG, Field CJ, Zijlstra RT, et al. The effects of pure nucleotides on performance, humoral immunity, gut structure and numbers of intestinal bacteria of newly weaned pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:3126–34.

Arnaud A, Lopez-Pedrosa JM, Torres MI, Gil A. Dietary nucleotides modulate mitochondrial function of intestinal mucosa in weanling rats with chronic diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:124–31.

Ortega MA, Gil ASanchez-Pozo A. Maturation status of small intestine epithelium in rats deprived of dietary nucleotides. Life Sci. 1995;56:1623–30.

Stein HH, Kil DY. Reduced use of antibiotic growth promoters in diets fed to weanling pigs: dietary tools, part 2. Anim Biotechnol. 2006;17:217–31.

Mardinoglu A, Shoaie S, Bergentall M, Ghaffari P, Zhang C, Larsson E, et al. The gut microbiota modulates host amino acid and glutathione metabolism in mice. Mol Syst Biol. 2015;11:834.

Bilinsky LM, Reed MC, Nijhout HF. The role of skeletal muscle in liver glutathione metabolism during acetaminophen overdose. J Theor Biol. 2015;376:118–33.

Xiao YP, Wu TX, Sun JM, Yang L, Hong QH, Chen AG, et al. Response to dietary L-glutamine supplementation in weaned piglets: a serum metabolomic comparison and hepatic metabolic regulation analysis. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:4421–30.

Board M, Humm S, Newsholme EA. Maximum activities of key enzymes of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, pentose phosphate pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle in normal, neoplastic and suppressed cells. Biochem J. 1990;265:503–39.

Krebs H. Glutamine metabolism in the animal body. In Glutamine: Metabolism, Enzymology, and Regulation. Edited by Mora J. New York, US.1980. 319–29.

Amelio I, Cutruzzola F, Antonov A, Agostini M, Melino G. Serine and glycine metabolism in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:191–8.

Wang WW, Qiao SY, Li DF. Amino acids and gut function. Amino Acids. 2009;37:105–10.

Wang WW, Dai ZL, Wu ZL, Lin G, Jia SC, Hu S, et al. Glycine is a nutritionally essential amino acid for maximal growth of milk-fed young pigs. Amino Acids. 2014;46:2037–45.

Fang ZF, Yao K, Zhang XL, Zhao SJ, Sun ZH, Tian G, et al. Nutrition and health relevant regulation of intestinal sulfur amino acid metabolism. Amino Acids. 2010;39:633–40.

Wu G, Meier SA, Knabe DA. Dietary glutamine supplementation prevents jejunal atrophy in weaned pigs. J Nutr. 1996;126:2578–84.

Acknowledgements

We thank all present and past members of Yan Laboratory who have contributed comments and ideas.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0500503 and 2018YFD0500404), the Natural Science Foundation of China (31730090), and Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2018CFA020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW, JH and XY designed the research. ZW, JH, XW, CX, WZ and TY conducted the research. ZW and XY wrote the paper with the help of all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the protocols (permit number: HZAUSW2013–0006) approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University. The animal care and maintenance were in compliance with the recommendations in the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals in China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Hu, J., Zheng, W. et al. Lactobacillus frumenti mediates energy production via fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver of early-weaned piglets. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 10, 95 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-019-0399-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-019-0399-5