Abstract

Purpose

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has commonly been used for evaluating cardiac function and monitoring hemodynamic parameters during complex surgical cases. Anesthesiologists may be dissuaded from using TEE in orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) out of concern about rupture of esophageal varices. Complications associated with TEE in OLT were evaluated.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed charts and TEE videos of all OLT cases from January 2003 through December 2013 at Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville, Florida).

Results

Of the 1811 OLTs performed, we identified 232 patients who underwent intraoperative TEE. Esophageal variceal status was documented during presurgical esophagogastroduodenoscopy in 230 of the 232 patients. Of these, 69 (30.0 %), had no varices; 113 (49.1 %), 41 (17.8 %), and 7 (3.0 %) had grades I, II, and III varices, respectively. Two patients (0.9 %) had no EGD performed because of acute liver failure. During OLT, 1 variceal rupture (0.4 %) occurred after placement of an oral gastric tube and TEE probe; the patient required intraoperative variceal banding. Most patients had preexisting coagulopathy at the time of probe placement. The mean (SD) laboratory test results were as follows: prothrombin time, 21.7 (6.6) seconds; international normalized ratio, 1.9 (1.3); partial thromboplastin time, 43.8 (13.3) seconds; platelet, 93.7 (60.8) × 1000/μL; and fibrinogen, 237.8 (127.6) mg/dL.

Conclusion

TEE was a relatively safe procedure with a low incidence of major hemorrhagic complications in patients with documented esophagogastric varices and coagulopathy undergoing OLT. It appeared to effectively disclose cardiac information and allowed rapid reaction for proper patient management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has become an important part of an anesthesiologist’s armamentarium for evaluating cardiac function and monitoring hemodynamic parameters during complex surgical cases. Patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) may present with cardiac dysfunction, either from preexisting coronary artery disease or associated liver pathophysiology (Carey et al. 1995; Zetterman et al. 1998). End-stage liver disease is often associated with a hyperdynamic state, resulting in reduced systemic venous resistance and increased cardiac output. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy can cause hemodynamic changes, diastolic and systolic dysfunction, electrophysiologic abnormalities, and segmental wall motion abnormalities (Fouad and Yehia 2014; Matsumori 2005; Teragaki et al. 2003; Omura et al. 2005; Therapondos et al. 2004), which might be assessed using TEE.

Intraoperative cardiovascular instability may be exacerbated by major blood loss. In the pre-anhepatic phase, hypotension may result from large fluid shifts after ascitic fluid removal or from decreased venous return caused by surgical manipulation of the liver. Cross-clamping the inferior vena cava or even using an inferior vena cava–sparing piggyback technique (Lerut et al. 1989) can decrease venous return in the anhepatic phase, regardless of the availability of venovenous bypass (Burtenshaw and Isaac 2006). Cardiac instability during reperfusion is common because of the immediate decreased venous return and cardiac output. TEE can help assess the myocardial response to inotropes and the changes in preload and afterload after reperfusion. TEE can also identify cardiac pathologies and hemodynamic conditions that would be otherwise unknown without the visualization of the myocardial function (Markin et al. 2015).

Intraoperative TEE has been proven safe and efficacious during cardiac surgery (Reeves et al. 2013), with rates of major bleeding complications ranging from 0.03 to 0.8 % (Hahn et al. 2013). Its use has become more common in OLT because it provides real-time visualization of cardiac function. The guidelines published by the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists in 2013 stated that intraoperative TEE is generically indicated for “noncardiac surgery when patients have known or suspected cardiovascular pathology which may impact outcomes.” (Hahn et al. 2013) However, TEE probe insertion in the presence of the coagulopathy common to end-stage liver disease can result in esophageal injury and variceal hemorrhage. Esophageal varices, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and recent upper gastrointestinal bleed are all listed as relative contraindications to TEE in the same published guidelines (Hahn et al. 2013). A limited number of retrospective reviews have evaluated the safety of intraoperative TEE in OLT and have suggested that TEE is a relatively safe method of monitoring intraoperative cardiac function, with rates of major hemorrhagic complications that range from none to 0.9 % in the overall OLT population and 2.8 % in patients with Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores of 25 or higher (Burger-Klepp et al. 2012; Suriani et al. 1996; Myo Bui et al. 2015; Markin et al. 2015). The goal of this study was to investigate the complications associated with the use of intraoperative TEE during OLT at our institution, adding new data to the open discussion regarding the safety of TEE in the OLT patient population.

Results

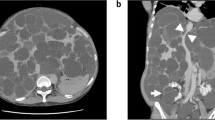

Of the 1811 patients undergoing OLT during the study period, 232 patients (12.8 %) had intraoperative TEE examinations, with a mean and median of 21 TEE examinations per year. The primary causes of end-stage liver disease of the study cohort are listed in Table 1. The most common indication for intraoperative TEE was hemodynamic monitoring, which was deemed beneficial by the anesthesiologists at their discretion. For hemodynamic monitoring, the TEE probe was inserted at the beginning of the procedure, after induction of general anesthesia. The second most common indication was emergent intraoperative TEE placement after a patient presented with hemodynamic instability or cardiac arrest. For these patients, TEE provided visual confirmation of intracardiac thrombosis (n = 4; Fig. 1) and dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (n = 2; Fig. 2). The indications for intraoperative TEE are listed in Table 2. In total, 7 anesthesiologists performed the TEE examinations during the study period; of these, 2 had advanced perioperative echocardiography training and 5 had basic perioperative echocardiography training.

Of the 232 TEE examinations, 55 (23.7 %) had archived documentation of transgastric views, whereas the remainder were limited to the midesophageal view. The coagulation laboratory profile of these patients immediately preceding TEE probe insertion was noted (Table 3). Most patients had preexisting coagulopathy at the time of probe placement. One case had documentation describing a difficult insertion, which prompted the anesthesiologist to withdraw the probe and cancel the intraoperative TEE examination.

Esophageal variceal status had been documented by EGD in 230 of the 232 patients with intraoperative TEE (Table 4). The patients with a history of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding and banding for treatment of esophageal varices are described in Table 5. Nearly all grade II and all grade III esophageal varices were banded during the transplant perioperative evaluation. Two patients (0.9 %) did not have EGD performed before OLT because of acute liver failure.

One patient had variceal rupture during OLT that occurred after placement of an orogastric tube and TEE probe (bleeding was observed in the oropharynx immediately after the insertion of the probe). Grade II bleeding esophageal varices were successfully banded during 2 preoperative EGD examinations performed 12 and 6 months before surgery. The patient again underwent EGD at 5 months and 2 weeks preoperatively; neither examination showed gastric varices and only trace esophageal varices were observed. The intraoperative upper endoscopy showed actively bleeding esophageal varices close to the gastroesophageal junction, where the gastroenterologist had successfully placed 4 bands to control the bleeding. Intraoperative coagulation parameters were as follows: PT, 16.7 s; PTT, 24.7 s; INR, 1.3; platelet count, 141 × 1000/μL; and fibrinogen, 342 mg/dL. No other complications (e.g., dental injury, oropharyngeal trauma, esophageal or gastric mucosa injury) were indicated.

In the remaining 1579 OLT patients without intraoperative TEE, 1 had an intraoperative variceal bleed without insertion of an orogastric tube or TEE probe in the esophagus. Coagulation parameters at the time of bleeding were as follows: PT, 33.6 s; PTT, 53.7 s; INR, 3.2; platelet count, 69 × 1000/μL; and fibrinogen, 94 mg/dL. The patient had grade I esophageal varices and gastric fundal varices. A Minnesota tube was placed by the gastroenterologist in the operating room with endoscopic guidance. The gastric balloon was insufflated and pulled against the gastroesophageal junction to stop the bleeding.

No dental injury, oropharyngeal trauma, esophageal or gastric mucosal injury, or death caused by TEE was found through our retrospective review of the immediate 24 h after the insertion of TEE probe.

Discussion

In our series, intraoperative TEE appeared to be relatively safe, with a low incidence of major hemorrhagic complications in patients with documented esophageal varices and coagulopathy. It was associated with an esophageal hemorrhage rate of 0.4 % and no deaths. No dental injury, oropharyngeal trauma, and esophageal or gastric mucosa injury was observed in the perioperative period. TEE permitted the intraoperative diagnosis of intracardiac thrombosis in 4 patients and LVOTO in 2 patients. Although uncommon, both conditions can be potentially lethal if not diagnosed and treated in an appropriate and timely fashion. Only 23.7 % of TEE examinations were performed with transgastric views, but midesophageal views were still useful for monitoring hemodynamic and cardiac function.

In our patients with intracardiac thrombosis, clear visualization of the thrombi by intraoperative TEE prompted either intentionally sustained coagulopathy or rapid administration of heparin or tissue plasminogen activator to promote thrombolysis and decrease the risk of the clot propagation into the pulmonary vasculature (Lerner et al. 2005). Although intracardiac thrombosis is a rare event during OLT, its early diagnosis may be crucial for survival (Peiris et al. 2015).

In the 2 patients with LVOTO found after liver reperfusion, hemodynamic instability did not improve with vasopressor administration and volume resuscitation. The pulmonary artery catheter readings were relatively unchanged with central venous pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, systolic pulmonary artery pressure, and systemic venous resistance in the period preceding hypotension. Only diastolic pulmonary artery pressure became elevated during hemodynamic instability. A TEE probe was inserted and showed dynamic LVOTO with systolic anterior motion of mitral valve. Because TEE images allowed direct visualization of the ventricular walls, the anesthesiologists were able to immediately discontinue epinephrine, start β-blocking medications, and use phenylephrine as the only vasoactive agent.

TEE initially was used reluctantly during OLT because of the potential for variceal rupture (De Wolf 1999). Per the practice guidelines for perioperative TEE published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force in 2010 (Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on transesophageal echocardiography 2010), esophageal varices are not an absolute contraindication to TEE. The guidelines recommend using TEE in patients with esophageal disease if the expected benefit outweighs the potential risk and appropriate precautions are taken (Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography 2010). Studies have reported that TEE significantly improved the intraoperative management of patients undergoing OLT (Suriani et al. 1996; Rafferty et al. 1993). One study, although not conducted during intraoperative OLT procedures, showed that “TEE without transgastric views can be performed without serious complications in patients with grade I or II esophageal varices who have not experienced recent variceal hemorrhages”(Spier et al. 2009).

Two patients in our review had documented variceal rupture. One presented immediately after placement of the TEE probe, whereas the other patient did not receive any instrumentation or manipulation of the esophagus. Spontaneous variceal rupture can be caused solely by increased portal pressure after clamping the portal system at the start of the anhepatic phase (Boin et al. 2004). Variceal hemorrhage and esophageal complications can occur after insertion of an orogastric tube for stomach decompression (Taniai et al. 2000; Casavilla et al. 1991; Stevenson et al. 1992). We hypothesize that clamping of the portal system at the start of the anhepatic phase caused portal pressure to increase, leading to spontaneous rupture of the gastric varices in the patient without intraoperative TEE.

Although the incidence rate of variceal bleeding or esophageal injury from intraoperative TEE probe insertion was low in our cohort, the risks and benefits should still be diligently assessed for each patient. When performing intraoperative TEE during OLT, we suggest having at least one assistant who monitors the patient’s vital signs, administers medications, suctions secretions, and otherwise attends to the patient’s needs; this assistant may be extremely valuable, considering the significant workload and attention required for this patient population. When TEE examinations are performed by experienced operators with strict vigilance, they have an acceptably low risk of complications (Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography 2010; Kallmeyer et al. 2001; Daniel et al. 1991). In summary, methods to decrease the likelihood of variceal rupture are listed in Table 6.

We acknowledge limitations of the study. With our observation limited to the perioperative period, late-presenting complications may contribute to a higher incidence of complications than what was reported here. Because of the retrospective study design, it was likely that only major complications such as esophageal perforation and massive hemorrhagic variceal rupture were documented in the charts. Minor hemorrhage, e.g., presence of blood-tinted secretions in the oropharynx, in the orogastric tube, or on the TEE probe upon removal likely were not documented. The study has a major risk of underreporting bias. Most patients with high-grade varices underwent preoperative banding, which may have lessened the risk of rupture. However, our review was underpowered to show the protective effect of variceal banding in preventing TEE-related variceal hemorrhage. Furthermore, TEE was not routinely used in all OLT cases. In patients without preoperative banding or with varices of unknown grade, TEE often was limited to midesophageal windows or was completely avoided. The decision to perform TEE was made by anesthesiologists, and potential bias in patient selection could not be eliminated. Future studies of prospective routine intraoperative TEE use are required to overcome these limitations.

Intraoperative TEE during OLT can provide valuable real-time data that may not be obtainable by other means during periods of potentially catastrophic hemodynamic instability, facilitating rapid reaction for proper intraoperative patient management. Our study suggests that intraoperative TEE was relatively safe to use, despite the risk of variceal hemorrhage. On the basis of our data and experience, we suggest intraoperative TEE for all OLT patients with a cardiac history and perioperative hemodynamic instability refractive to treatment. Critical information provided by TEE may facilitate more accurate fluid and hemodynamic management through direct observation of ventricular size, valve function, myocardial performance, and acute thrombotic events (Burtenshaw and Isaac 2006; Hofer et al. 2004). Performing TEE examinations in all OLT surgeries may be a challenge due to the availability of the TEE equipment and TEE trained anesthesiologists in some institutions. TEE operators still face the same potential complications of esophageal perforation, esophageal tear, hematoma, laryngeal palsy, dysphagia, dental injury, and death(Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography 2010; Hilberath et al. 2010; Piercy et al. 2009). The risks and benefits should be carefully considered. The anesthesia and surgical teams should be ready to treat possible complications associated with TEE insertion.

Conclusions

Concerns about esophageal variceal rupture in patients with coagulopathy may deter anesthesiologists from using intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) during orthotopic liver transplantation. A retrospective review of 232 patients with documented esophagogastric varices and coagulopathy showed TEE was relatively safe, with a low incidence of major hemorrhagic complications.

Methods

After obtaining approval from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board in November 2011, we conducted a retrospective chart and TEE video review of all OLT cases at Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville, Florida, USA) from January 2003 through December 2013. Patients were excluded if they did not undergo intraoperative TEE placement or if they had incomplete medical records regarding use of the TEE probe.

Pre-surgical esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed to determine the severity of the esophageal varices and the history of endoscopic variceal band ligation. In patients with multiple EGD examinations, the most recent report before the OLT was analyzed. Esophageal varices were graded by gastroenterologists as absent, grade I (small, straight varices <5 mm), grade II (enlarged, tortuous varices <5 mm, occupying less than one-third of the lumen), and grade III (large, coil-shaped varices >5 mm occupying more than one-third of the lumen); grading was determined with the esophagus insufflated (Peck-Radosavljevic et al. 2005; Garcia-Tsao et al. 2007). The history of prior upper gastrointestinal bleeding in relation to intraoperative variceal bleed also was evaluated.

Omniplane TEE probes (Philips Model 21378A and 21369A) were used. The attending anesthesiologists performed probe placements and examinations during OLT. An orogastric tube was inserted to empty the stomach and then removed before insertion of the TEE probe. If blind insertion of the TEE probe was not successful, the general approach was to insert the probe using direct or video laryngoscopy. TEE probe tip position was limited to midesophageal views (for monitoring volume status, ventricular contractility, and valvular function) or were advanced to a transgastric view as part of a full evaluation. The transgastric view was omitted in patients with a history of varices because the distal 2–5 cm of the esophagus is the most common site of varices (Sharara and Rockey 2001). It was also a clinical decision, made by the anesthesiologists, to not advance the TEE probe in patients without a history of varices. The number of TEE procedures with limited midesophageal views vs a full examination with transgastric views were recorded. The TEE probe was put in “freeze” mode when not obtaining images and was removed at the end of surgery, before leaving the operating room.

Electronic record laboratory data for prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalized ratio (INR), platelet counts, and fibrinogen counts immediately before TEE probe insertion were reviewed. Data are presented as mean (SD), median, and interquartile range. We evaluated any major perioperative complications to determine whether TEE usage was associated with the severity of esophageal varices and coagulation status. Documentations by physicians and nursing staffs from the time in the operating room to 24 h postoperatively were reviewed for evidence of TEE-related complications. Complications were defined as dental injury (chipping or loss of teeth), oropharyngeal trauma (mucosal tear in the oropharyngeal area), esophageal or gastric mucosa injury (tissue tear confirmed by a gastroenterologist via upper endoscopy), or variceal hemorrhage (variceal rupture confirmed by a gastroenterologist via upper endoscopy).

Abbreviations

- EGD:

-

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- INR:

-

international normalized ratio

- LVOTO:

-

left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- OLT:

-

orthotopic liver transplantation

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- PTT:

-

partial thromboplastin time

- TEE:

-

transesophageal echocardiography

References

Aniskevich S, Shine TS, Shapiro DP (2010) Acute gastric variceal bleeding during orthotopic liver transplant. Exp Clin Transplant 8(3):266–268

Augoustides JG, Hosalkar HH, Milas BL, Acker M, Savino JS (2006) Upper gastrointestinal injuries related to perioperative transesophageal echocardiography: index case, literature review, classification proposal, and call for a registry. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 20(3):379–384. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2005.10.011

Boin IF, Leonardi LS, Oliveira GR, Luzo AC, Carvalho MA, Cardoso AR, Caruy CA (2004) Gastrointestinal bleeding during liver transplantation–report of two cases. Hepatogastroenterology 51(60):1825–1826

Burger-Klepp U, Karatosic R, Thum M, Schwarzer R, Fuhrmann V, Hetz H, Bacher A, Berlakovich G, Krenn CG, Faybik P (2012) Transesophageal echocardiography during orthotopic liver transplantation in patients with esophagoastric varices. Transplantation 94(2):192–196. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e31825475c2

Burtenshaw AJ, Isaac JL (2006) The role of trans-oesophageal echocardiography for perioperative cardiovascular monitoring during orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 12(11):1577–1583. doi:10.1002/lt.20929

Carey WD, Dumot JA, Pimentel RR, Barnes DS, Hobbs RE, Henderson JM, Vogt DP, Mayes JT, Westveer MK, Easley KA (1995) The prevalence of coronary artery disease in liver transplant candidates over age 50. Transplantation 59(6):859–864

Casavilla A, Moysiuk Y, Stieber AC, Starzl TE (1991) Esophageal complications in orthotopic liver transplant patients. Transplantation 52(1):150–151

Daniel WG, Erbel R, Kasper W, Visser CA, Engberding R, Sutherland GR, Grube E, Hanrath P, Maisch B, Dennig K et al (1991) Safety of transesophageal echocardiography. A multicenter survey of 10,419 examinations. Circulation 83(3):817–821

De Wolf A (1999) Transesophageal echocardiography and orthotopic liver transplantation: general concepts. Liver Transpl Surg 5(4):339–340. doi:10.1002/lt.500050408

Fouad YM, Yehia R (2014) Hepato-cardiac disorders. World. J Hepatol 6(1):41–54. doi:10.4254/wjh.v6.i1.41

Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey WD (2007) Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 102(9):2086–2102. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01481.x

Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, Bruce CJ, Glas KE, Lang RM, Reeves ST, Shanewise JS, Siu SC, Stewart W, Picard MH (2013) Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26(9):921–964. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2013.07.009

Hilberath JN, Oakes DA, Shernan SK, Bulwer BE, D’Ambra MN, Eltzschig HK (2010) Safety of transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 23(11):1115–1127. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2010.08.013

Hofer CK, Zollinger A, Rak M, Matter-Ensner S, Klaghofer R, Pasch T, Zalunardo MP (2004) Therapeutic impact of intra-operative transoesophageal echocardiography during noncardiac surgerys. Anaesthesia 59(1):3–9

Kallmeyer IJ, Collard CD, Fox JA, Body SC, Shernan SK (2001) The safety of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography: a case series of 7200 cardiac surgical patients. Anesth Analg 92(5):1126–1130

Kharasch ED, Sivarajan M (1996) Gastroesophageal perforation after intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. Anesthesiology 85(2):426–428

Lerner AB, Sundar E, Mahmood F, Sarge T, Hanto DW, Panzica PJ (2005) Four cases of cardiopulmonary thromboembolism during liver transplantation without the use of antifibrinolytic drugs. Anesth Analg 101(6):1608–1612. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000184256.28981.2B

Lerut J, Gertsch P, Blumgart LH (1989) “Piggy back” adult orthotopic liver transplantation. Helv Chir Acta 56(4):527–530

Markin NW, Sharma A, Grant W, Shillcutt SK (2015) The safety of transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 29(3):588–593. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2014.10.012

Matsumori A (2005) Hepatitis C virus infection and cardiomyopathies. Circ Res 96(2):144–147. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000156077.54903.67

Myo Bui CC, Worapot A, Xia W, Delgado L, Steadman RH, Busuttil RW, Xia VW (2015) Gastroesophageal and hemorrhagic complications associated with intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients with model for end-stage liver disease score 25 or higher. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 29(3):594–597. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2014.10.030

Na S, Kim CS, Kim JY, Cho JS, Kim KJ (2009) Rigid laryngoscope-assisted insertion of transesophageal echocardiography probe reduces oropharyngeal mucosal injury in anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology 110(1):38–40. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318190b56e

Omura T, Yoshiyama M, Hayashi T, Nishiguchi S, Kaito M, Horiike S, Fukuda K, Inamoto S, Kitaura Y, Nakamura Y, Teragaki M, Tokuhisa T, Iwao H, Takeuchi K, Yoshikawa J (2005) Core protein of hepatitis C virus induces cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 96(2):148–150. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000154263.70223.13

Peck-Radosavljevic M, Trauner M, Schreiber F (2005) Austrian consensus on the definition and treatment of portal hypertension and its complications. Endoscopy 37(7):667–673. doi:10.1055/s-2005-861464

Peiris P, Pai SL, Aniskevich S 3rd, Crawford CC, Torp KD, Ladlie BL, Shine TS, Taner CB, Nguyen JH (2015) Intracardiac thrombosis during liver transplant: a 17-year single-institution study. Liver Transpl. doi:10.1002/lt.24161

Piercy M, McNicol L, Dinh DT, Story DA, Smith JA (2009) Major complications related to the use of transesophageal echocardiography in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 23(1):62–65. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2008.09.014

Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography (2010). Anesthesiology 112(5):1084–1096. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c51e90

Rafferty T, LaMantia KR, Davis E, Phillips D, Harris S, Carter J, Ezekowitz M, McCloskey G, Godek H, Kraker P et al (1993) Quality assurance for intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography monitoring: a report of 846 procedures. Anesth Analg 76(2):228–232

Reeves ST, Finley AC, Skubas NJ, Swaminathan M, Whitley WS, Glas KE, Hahn RT, Shanewise JS, Adams MS, Shernan SK (2013) Basic perioperative transesophageal echocardiography examination: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26(5):443–456. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2013.02.015

Sharara AI, Rockey DC (2001) Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 345(9):669–681. doi:10.1056/NEJMra003007

Spier BJ, Larue SJ, Teelin TC, Leff JA, Swize LR, Borkan SH, Satyapriya A, Rahko PS, Pfau PR (2009) Review of complications in a series of patients with known gastro-esophageal varices undergoing transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 22(4):396–400. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2009.01.002

Stevenson WC, Sawyer RG, Pruett TL (1992) Recurrent variceal bleeding after liver transplantation–persistent left-sided portal hypertension. Transplantation 53(2):493–495

Suriani RJ, Cutrone A, Feierman D, Konstadt S (1996) Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 10(6):699–707. doi:10.1016/S1053-0770(96)80193-5

Taniai N, Harihara Y, Kita Y, Hirata M, Sano K, Kubota K, Takayama T, Kawarasaki H, Makuuchi M, Yoshida H, Akimaru K, Tajiri T, Onda M (2000) Rupture of newly developed esophageal varices after adult-to-adult living-related liver transplantation. Transplant Proc 32(7):2264–2265

Teragaki M, Nishiguchi S, Takeuchi K, Yoshiyama M, Akioka K, Yoshikawa J (2003) Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart Vessels 18(4):167–170. doi:10.1007/s00380-003-0705-0

Therapondos G, Flapan AD, Plevris JN, Hayes PC (2004) Cardiac morbidity and mortality related to orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 10(12):1441–1453. doi:10.1002/lt.20298

Zetterman RK, Belle SH, Hoofnagle JH, Lawlor S, Wei Y, Everhart J, Wiesner RH, Lake JR (1998) Age and liver transplantation: a report of the liver transplantation database. Transplantation 66(4):500–506

Authors' contributions

S-LP: conduct of the study, collection of data, analysis and interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, SAIII: design and conduct of the study, collection of data. NGF, BLL, CCC, KDT: review the manuscript. PP: preparation and review of the manuscript. TSS: design of the study and review the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pai, SL., Aniskevich, S., Feinglass, N.G. et al. Complications related to intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in liver transplantation. SpringerPlus 4, 480 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1281-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1281-3