Abstract

One of the main pests of commercial rose crops in Colombia is the phytophagous mite Tetranychus urticae Koch. To manage this pest, synthetic chemicals have traditionally been used, some of which are well known to be potentially toxic to the environment and humans. Therefore, alternative strategies for pest management in greenhouse crops have been developed in recent years, including biological control with natural enemies such as parasitoids, predators and entomopathogenic microorganisms as well as chemical control using plant extracts. Such extracts have shown toxicity to insects, which has positioned them as a common alternative in programs of integrated pest management. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of an unfractionated ethanolic extract of Cnidoscolus aconitifolius leaves on adult females of T. urticae under laboratory conditions. The extract was chemically characterized by recording its metabolic profile via liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry, along with tentative metabolite identification. The immersion technique and direct application to rose leaves were used to evaluate the effects of seven doses (10–2,000 µg/mL) of the ethanol extract of C. aconitifolius leaves on T. urticae females under laboratory conditions. The mortality and oviposition of individuals were recorded at 24, 48 and 72 h. It was found that the C. aconitifolius leaf extract reduced fertility and increased mortality in a dose-dependent manner. The main metabolites identified included flavonoid- and sesquiterpene-type compounds, in addition to chromone- and xanthone-type compounds as minor constituents with potential acaricidal effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

One of the main pests affecting the rose crops in greenhouses is the phytophagous mite Tetranychus urticae (Nachman and Zemek 2002). The spider mites are mainly found on the central and secondary veins of the leaves, and when populations begin to increase, they distribute across the whole leaf (Aponte and McMurtry 1997; Hilarión et al. 2008), reaching high infestation levels and eventually causing leaf drop. This phytophagous species thrives under conditions of high temperature and low relative humidity, displaying explosive growth. It disperses by wind and is also carried on clothing or equipment used in crop management (Hussey and Scopes 1985). Under greenhouse conditions, these pests are distributed in foci due to a reduced ability to move autonomously over long distances (Murillo 1996). It has been noted that certain pesticides can stimulate reproduction, and the use of biological control for predatory mites may therefore be a promising strategy in this type of crop (Powell and Lindquist 1994). The control of this pest has focused on the use of synthetic chemical miticides. However, it is increasingly necessary to supplement this practice with more sustainable tools, for the sake of both the natural environment and humans (Gómez et al. 2004), accompanied by a plan for integrated management of pests and diseases that includes the use of natural enemies, such as predatory mites (usually the family Phytoseiidae), (Osborne et al. 1985; Moraes 1991; Pedigo 1996), and the use of biologically synthesized substances, such as extracts of plant and fungal origin.

Plant extracts, commonly referred to as botanical insecticides, show insecticidal and acaricidal properties at different levels regulating pest populations, despite being unconventional alternatives (Venzon et al. 2005). These extracts contain secondary metabolites produced by plants that have the potential to provide protection against phytophagous organisms and pathogens, and it has been found that these plant extracts also show antifungal properties (Alves 1998). Extracts of Cnidoscolus aconitifolius have been studied in several parts of the world, revealing lethal, sublethal and repellent effects on insects (Calderón-Montaño et al. 2011; Ferreira and Moore 2011) and phytophagous mites such as T. urticae (Yoon et al.1998; Soto et al. 2011; Asharaja and Sahayaraj 2013). Thus, as part of our research on control of economically-important pests and to generate new knowledge that can be applied by growers to manage the phytophagous mite T. urticae, the aim of this study was to determine the effect of an unfractionated ethanol-soluble extract of C. aconitifolius leaves under laboratory conditions, to provide alternative medium-term strategies to boost compliance with requirements regarding “clean products” for export.

Methods

Biological material

Collection of C. aconitifolius plants (commonly known as arnica) was performed in the Municipality of Agua Azul (Casanare, Colombia) in 2012. Subsequently, the collected plants were identified in collaboration with the Colombian National Herbarium of the Institute of Natural Sciences (National University of Colombia). A voucher specimen was deposited under the collection code COL389957. The individuals of T. urticae used for the experiments were collected from a rearing system for this phytophagous species maintained under greenhouse conditions (16.9 ± 2°C and RH of 73.0 ± 0.22%) at the Nueva Granada Military University. From these individuals, a new cohort was obtained to assess 2-days adults, which is appropriate for evaluating the effect of the extracts.

Extraction of plant material

To prepare the ethanol-soluble extract, plant material (leaves) was dried, ground, and subjected to extraction via maceration (for 7 days) using 96% ethanol, with daily solvent removal.

High-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis (HPLC–MS)

The ethanol extract was analyzed via liquid chromatography using a Shimadzu LCMS 8030 system (Shimadzu Corp., Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan). Separation of the components of the extract was performed on a C-18 standard Premier column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm) using an LC–MS system consisting of a separation module equipped with a photodiode array detector (DAD), electrospray ionization (ESI) and a detector with a triple quadrupole mass analyzer. The flow rate was 0.7 mL/min, and for the mobile phases, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 0.005% acetonitrile (ACN) were used. The applied concentration was 1.0 µg/mL in absolute ethanol, and 10 µL of this solution was injected into the LC system. The mass spectrometry method described by Timóteo et al. (2014), Proestos et al. (2006) and Fraser et al. (2014) was used, with the following modifications: a scan using positive and negative ionization mode was performed with an acquisition time of 2–33 min, a mass range of 50–800 m/z, a scan speed of 1,667 μ/s, an event time of 0.5 s, nebulizer gas flow of 1.5 L/min, 350°C interface temperature and DL, and 450°C block temperature. The drying gas flow rate was 9 L/s. The analysis was monitored at wavelengths between 270 and 330 nm. Tentative identification of the major and minor metabolites in the experimental extract was performed through the analysis of mass spectra based on the LC–MS data, complemented with the analysis of retention times. These identifications were supported by the database included in the MassBank Project search engine (free distribution).

Effect of the Cnidoscolus aconitifolius leaf extract on T. urticae females

To evaluate the effect of the C. aconitifolius leaves extract, an experiment was performed under a completely randomized design with seven concentrations of the plant extract (Arnica or Chaya), an absolute control and a positive control (Table 1), for a total of nine treatments, each one with three replicates. The experiment was replicated three times over time.

Assays were performed at the laboratory of Biological Control (19 ± 0.2°C and 60 ± 2%) of the Nueva Granada Campus at the Nueva Granada Military University, located in Cajicá, Cundinamarca, Colombia.

The experimental unit consisted of a Petri dish 6 cm in diameter, within which a bean leaf disc was placed, rounded with swab. Subsequently, the experimental unit was sealed with stretch film. A total of 20 females of T. urticae at 2 days of age were placed on the underside of the leaf bean. Once the extracts were applied in each of the experimental units, they were maintained in the Biological Control laboratory (20.5 ± 1°C and 58.6 ± 3% RH) to complete the recording of data.

Application of the ethanol extract of the leaves of C. aconitifolius was performed as follows: each bean leaf disk was immersed in a dilution of the C. aconitifolius extract for 15 min, followed by exposure to a gentle stream of air to remove excess of moisture, after which this disc was placed in the experimental unit. Finally, direct application of the extract to the T. urticae females present in the experimental unit was performed. Direct application was performed on individuals using an airbrush held at a 20 cm height from the experimental unit, calibrated at 96 drops/cm2, with a pressure of 20–30 PSI. The mortality and fecundity of T. urticae were recorded at 24, 48 and 72 h using a stereoscope. Thus, the mortality of T. urticae individuals was confirmed by a smooth movement no greater than the length of insect body after soft contact with a fine haired brush (Ponte Teles et al. 2011).

Data analysis

Using the obtained data, daily corrected mortality was calculated for each of the three days of the trial, in the three replicates conducted over time, using Abbott’s formula (Abbott 1925):

The corrected mortality of the T. urticae females recorded at 72 h was transformed using the function \(y = ar\sin \sqrt p\), where p is the mortality ratio, and “y” is the transformed value. To assess the significant differences between treatments, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used. Logistic regression models were fitted using the generalized linear model technique assuming a binomial distribution and using the logit link function to determine the median lethal dose (LC50) at different times of evaluation. The analyses were performed in the statistical language R, version 3.1.2 (Grainge and Ahmesds 1988).

Results

Effect of the ethanol extract of the leaves of C. aconitifolius on T. urticae females

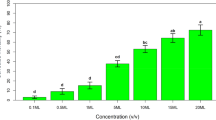

It was found that doses of 600, 1,200 and 2,000 µg/mL of the ethanol extract of C. aconitifolius leaves resulted in higher mortality of T. urticae females. Although significant differences between treatments (p = 2.2 × 10−16) were obtained, the only concentration that did not show a significant difference from the positive control (commercial acaricide) was the highest dose (2,000 µg/mL) (Table 2). This result could indicate that this concentration might be the most effective for producing a formulation for later use in commercial crops to control adult T. urticae.

On the other hand, it can be observed in Table 2 that the mortalities induced by doses between 1,200 and 2,000 µg/mL were between 62 and 92%, with the highest concentration (2,000 µg/mL) causing the highest mortality among females of T. urticae.

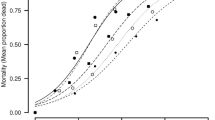

In Table 3, it can be observed that the median lethal dose (LC50) decreased with an increasing time of exposure of T. urticae females to the plant extract.

The obtained values of fecundity (Table 4) showed statistically significant differences between the different concentrations of the extract of C. aconitifolius leaves at 24, 48 and 72 h (p = 4.04 × 10−7, p = 1.20 × 10−7, p = 2.20 × 10−16, respectively). At 48 and 72 h, it can be observed that the absolute control (no application or 0 µg/mL) displayed significantly higher fecundity than was observed under all doses of the extract. At 48 h, the effect of all doses was similar, while at 72 h, doses between 50 and 2,000 µg/mL induced greater reductions of fecundity compared with the control and the 10 µg/mL dose.

HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS analysis on plant extract

The chromatographic profile (Figure 1) of the ethanol extract of C. aconitifolius leaves showed two peaks corresponding to the major components 1 and 2, which were identified as flavonoids (tR = 2.24 and 2.54 min). The third compound identified (tR = 4.89 min) may be a phenolic compound or derivative, which is consistent with the findings reported by Omotoso et al. (2014), who identified phenolic compounds in an C. aconitifolius leaf extract using UV–VIS techniques, FTIR and GC–MS.

The detailed analysis of the UV–Vis and mass spectra for each component allowed the tentative identification of 14 compounds in the C. aconitifolius leaf extract (Table 5). The main compounds identified were flavonoids (hispidulin sulphate, eucalyptin, and epigallocatechin di-O-gallate) and a sesquiterpene (triptofordin D1). The minor compounds identified in the plant extracts were flavonoids ((epi)catechin di-O-gallate and acutifolin D), coumarin (fraxetin), a chromone (hamaudol), xanthones (moreollic acid, polyanxanthone C, cadensin G, parvixanthone D) and lignan (tiegusanin F).

Discussion

According to the results presented in Table 2, the mortality of male T. urticae behaved in a dose-dependent manner. This is consistent that the findings reported by Castagnoli et al. (2005), Numa et al. (2011) and Sivira et al. (2011), who observed that increasing the concentration of the extract applied to T. urticae adults, the mortality was also increased, in addition to reducing the fertility of the phytophagous females.

A study reported that mortality of T. urticae reached a value of 69% using ethanol-soluble Croton sellowii extracts, which indicates that there are plants with good acaricide and even repellent effects (Pontes Teles el al. 2011). On comparing the results of the present work, it was found corrected mortalities of 92% (Table 2), which is comparable with that of the positive control used (commercial acaricide with chlorfenapyr as active ingredient).

Table 2 also shows that the mortality caused by C. aconitifolius extract is statistically the same to that registered with the commercial acaricide. However, the highest effect of C. aconitifolius extract was achieved using the highest dose (2,000 µg/mL). This fact could be rationalized since plant extracts have low concentrations of active components requiring higher concentrations of the extract in comparison to other products.

Additionally, it can also be noted from Table 2 that there were no significant differences in the mortality generated by doses of 10–50 µg/mL, which caused the lowest recorded mortalities. In addition to these results, it is evident from the same table that the mortality induced in T. urticae adults did not reach 50% for doses between 10 and 600 µg/mL. This result might indicate that, as established by Gou et al. (1998) and Shi et al. (2008), these concentrations are not appropriate for use as an acaricide for the control of this phytophagous species in commercial crops.

On the other hand, in Table 3, it can be observed that the median lethal dose (LC50) decreased with an increasing time of exposure of the T. urticae females to the ethanol extract. This result agrees with the findings of Hincapié et al. (2008), Shi et al. (2008) and Teles et al. (2007), who noted that increasing the exposure time of the phytophage to the product can result in toxic interference in biochemical and physiological functions in herbivores, resulting in a decrease of the LC50. However, the overlapped confidence interval limits between 48 and 72 h indicated that there were no significant differences.

The results shown in Table 4 indicate that the ethanol extract of the leaves of C. aconitifolius causes a reduction in the number of eggs laid per female per day. This is consistent with the results established by Soto et al. (2011), who reported that application of plant extracts may affect the oviposition of T. urticae females.

Although the differences between fertility recorded for the different concentrations of the ethanol extract were not significant, a trend towards diminishing fecundity with an increasing dose can be noted in Table 4. These results are consistent with previous reports by Castiglioni et al. (2002), Siviria et al. (2011) and Asharaja and Sahayaraj (2013), who postulated that the number of eggs laid per female decreases when an increasing concentration of a plant extract is applied, which could be associated with possible sublethal effects of extracts on T. urticae females. However, it was observed in the tests that eggs laid per alive female were higher in comparison to the evaluated concentrations for C. aconitifolius and the positive control (Table 4). This observation is consistent to that reported by Nicastro et al. (2013), who found that a chlorfenapyr resistance was generated by T. urticae involving a decreased mortality and an increased fertility. This fact is also consistent to the study by James and Price (2002), who observed that the spray-applied imidacloprid increased the egg production of T. urticae by 19–23%.

The two major components observed in the chromatographic profile (Figure 1) corresponded to flavonoids, which agrees with the findings of Awoyinka et al. (2007), Zavoi et al. (2011) and Neha and Jyoti (2013), who indicated that the typical spectrum of flavonoids consists of two peaks with maximum absorption in the 230–340 nm range. The major flavonoids hispidulin sulphate and eucalyptin (Figure 1; Table 5) from plants belonging to the Euphorbiaceae family have been reported to be effective for the control of insects and microorganisms such as bacteria (Calderón-Montaño et al. 2011; Ferreira and Moore 2011; Takahashi et al. 2004) and could have played an important role in the mortalities recorded in Tables 2 and 3. In addition, the presence of terpenes in the extract of the leaves of C. aconitifolius (specifically sesquiterpenes, Table 5) indicates that the plant could present an insect repellent effect on T. urticae. This result agree with those reported by Yoon et al. (1998), Garcia et al. (1995) and Escalante-Erosa et al. (2004), who found that some sesquiterpenes show a repellent effect against T. urticae.

Xanthones have been reported in plants of the Magnoliopsida class, to which C. aconitifolius belongs. However, there are no reports of insecticide and acaricide activity for these type of compounds, whereas they have been found to show activity against bacteria, yeasts and crustaceans (Tala et al. 2013). Although the compound hamaudol (chromone-type, Figure 1; Table 5) was a minor constituent of the plant extract, it could be considered as an important metabolite with acaricidal activity. It has been reported by Morimoto et al. (2003) that this compound occurs in plants of the Magnoliopsida class that and it shows antifeedant activity in Lepidoptera. In addition, fraxetin (coumarin, Table 5) could be an interesting metabolite regarding use in the control of T. urticae. Moreira et al. (2007) have reported that coumarins show insecticidal activity in several species of Coleoptera.

In conclusion, the unfractionated C. aconitifolius leaf-derived extract reduced fertility and increased mortality on T. urticae in a dose-dependent manner, possessing a good acaricidal profile to be used for the control of this phytophagous species in commercial crops. The tentative identification of metabolites performed in the present work provides important information supporting the acaricidal activity of the tested plant extract. However, prior to formulation of the ethanol extract, it will be necessary to perform isolation of the compounds it contains (following a bioguided fractionation protocol), in addition to the full chemical characterization and preliminary tests to establish which of the compounds are responsible for the observed acaricidal activity. Additionally, it is recommended that before including this plant extract in an integrated pest management program for T. urticae, compatibility tests should be conducted with natural enemies of this phytophagous species, such as predatory mites (Phytoseiulus persimilis and Neoseiulus californicus). Such tests are necessary because some compounds might also affect predators through behavior modification or lethal and sublethal effects, reducing their ability to predate T. urticae, and facilitating the establishment of T. urticae in commercial crops where predators are most often released to manage this important pest.

References

Abbott WS (1925) A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticides. J Econ Entomol 18:265–267

Alves S (1998) Controle microbiano de insetos. Fundação de Estudos Agrários Luiz de Queiroz (FEALQ), Piracicaba, Sao Paulo, Brasil, pp 1163

Aponte O, McMurtry JA (1997) Damage on ‘Hass’ avocado leaves, webbing and nesting behavior of Oligonychus perseae (Acari:Tetrnychidae). Exp Appl Acarol 21:265–272

Asharaja A, Sahayaraj K (2013) Screening of insecticidal activity of brown macroalgal extracts against Dysdercus cingulatus (Fab.) (Hemiptera: Pyrrhocoridae). J Biopest 6(2):193–203

Awoyinka OA, Balogun IO, Ogunnowo AA (2007) Phytochemical screening and in vitro bioactivity of Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (Euphorbiaceae). J Med Plants Res 1(3):63–65

Calderón-Montaño JM, Burgos-Morón E, Pérez-Guerrero C, López-Lázaro M (2011) A Review on the Dietary Flavonoid Kaempferol. Mini-Rev Med Chem 11:298–344

Castagnoli M, Liguori M, Simoni S, Duso C (2005) Toxicity of some insecticides to Tetranychus urticae, Neoseiulus californicus and Tydeus californicus. Biocontrol 50:611–622

Castiglioni E, Vendramin J, Tamai M (2002) Evaluación del efecto tóxico de extractos acuosos y derivados de meliáceas sobre Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Agrociencia 6:75–82

Escalante-Erosa F, Ortegón-Campos I, Parra-Tabla V, Peña-Rodríguez L (2004) Chemical Composition of the Epicuticular Wax of Cnidoscolus aconitifolius. J Mex Chem Soc 48:24–26

Ferreira MM, Moore SJ (2011) Plant-based insect repellents: a review of their efficacy, development and testing. Malar J 10(1):2–15

Fraser K, Lane G, Otter D, Harrison S, Quek S-Y, Hemar Y et al (2014) Non-targeted analysis by LC-MS of major metabolite changes during the oolong tea manufacturing in New Zealand. Food Chem 151:394–403

García S, Heinzen H, Hubbuch C, Martínez R, De Vries X, Moyna P (1995) Triterpene methyl ethers from palmae epicuticular waxes. Phytochem 39:1381–1382

Gómez S, Páez MM, Barreto C, García M, Cure JR, Torrado E (2004) Introducción del depredador Phytoseiulus persimilis como componente del manejo integrado de la arañita roja Tetranychus urticae. Asocolflores, pp 43–57

Grainge M, Ahmesds A (1988) Handbook of plant with pest control properties. Wiley, New York, p 470

Guo FY, Zang ZQ, Zhao ZM (1998) Pesticide resistence of Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Acari: Tetranychidae) in China. A review. Syst Appl Acarol 3:3–7

Hilarión A, Niño A, Cantor F, Rodriguez D, Cure JR (2008) Criterios para la liberación de Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias Henriot (Parasitiformes: Phytoseiidae) em cultivo de rosa. Agron Col 26(1):68–77

Hincapié CA, López GE, Torres R (2008) Compatison and characterization of garlic (Allium sativum L.) bulbs extracts and their effect on mortality and repellency of Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Chil J Agr Res 68(4):317–327

Hussey NW, Scopes N (1985) Biological Pest Control The Glasshouse Experience. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, pp 50–51

James DG, Price TS (2002) Fecundity in Twospotted Spider Mite (Acari: Tetranychidae) is Increased by Direct and Systemic Exposure to Imidacloprid. Ecotoxicology 95(4):729–732

Moraes GJ (1991) Biological and insect pest management. Controle Biológico de Ácaros Fitófagos. Bulletin 1911. Agric Exp Station 15(167):55–59

Moreira M, Picanço MC, Almeida-Barbosa LC, Carvalho-Guedes R, Campos M, Silva GA et al (2007) Plant compounds insecticide activity against Coleoptera pests of stored products. Pesq Agropec Bras 42(7):909–915

Morimoto M, Tanimoto K, Nakano S, Ozaki T, Komai K (2003) Insect antifeedant activity of favones and chromones against Spodoptera lituna. J Agric Food Chem 51:389–393

Murillo A (1996) Consideraciones para el manejo de ácaros en flores de exportación. SOCOLEN Comité Regional De Cundinamarca. Seminario Reconocimiento, hábitos y manejo de ácaros en flores. Bogotá, Colombia, pp 43–53

Nachman G, Zemek R (2002) Interactions in a tritrophic acarine predator-prey metapopulation system III: Effects of Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) on host plant condition. Exp Appl Acarol 25:27–42

Neha S, Jyoti S (2013) Phytochemical Analysis of Boµgainvillea glabra Choisy by FTIR and UV-VIS Spectroscopic Analysis. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 21(1):196–198

Nicastro R, Sato M, Valter A, Silva M (2013) Chlorfenapyr resistance in the spider mite Tetranychus urticae: stability, cross-resistance and monitoring of resistance. Phytoparasitica 41(5):303–305

Numa VSJ, Bustos HA, Rodriguez CD, Cantor RF (2011) Laboratory and greenhouse evaluation of the entomopathogenic fungi and garlic-pepper extract on the predatory mites, Phytoseiulus persimilis and Neosuiulus californicus and their effect on the spider mite Tetranychus urticae. Biol Control 57:143–149

Omotoso AE, Kenneth E, Mkparu KI (2014) Chemometric profiling of methanolic leaf extract of Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (Euphorbiaceae) using UV-VIS, FTIR and GC-MS techniques. J Med Plants Res 2(1):6–12

Osborne LS, Ehler LE, Nechols JS (1985) Biological control of two-spotted spider mite in greenhouses. University of Florida, Mid- Florida Research and Education Center, Apopka, FL, Technical Bulletin, pp 853–940

Pedigo LP (1996) Entomology and Pest Management, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, pp 301–315

Ponte Teles WJ, Oliveira JCG, Cámara CAG, Assis CPO, Oliveira JV, Junior MG et al (2011) Effects of the Ethanol Extracts of Leaves and Branches from Four Species of the Genus Croton on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). BioAssay 6(3):1–5

Powell C, Lindquist RK (1994) El manejo integrado de los insectos, ácaros y enfermedades en los cultivos ornamentales. Ball Publishing, Batavia, pp 31–32

Proestos C, Sereli D, Komatis M (2006) Determination of phenolic compounds in aromatic plants by RP-HPLC and GC-MS. Food Chem 95:44–52

Shi WB, Zhang L, Feng MG (2008) Time-concentration-mortality responses of carmine spider mite (Acari: Tetranychidae) females to three hypocrealean fungi os biocontrol agentes. Biol Control 46:495–501

Sivira A, Sanabria ME, Valera N, Vásquez C (2011) Toxicity of Ethanolic Extracts from Lippia origanoides and Gliricidia sepium to Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Boisduval) (Acari: Tetranychidae). Neotrop Entomol 40(3):375–379

Soto A, Oliveira HG, Pallini A (2011) Integración de control biológico y de productos alternativos con Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychydade). Rev U.D.C.A. 14(1):23–29

Takahashi T, Kokubo R, Sakaino M (2004) Antimicrobial activities of eucalyptus leaf extracts and flavonoids from Eucalyptus maculata. Lett Appl Microbiol 39(1):60–64

Tala M, Tchakam P, Wabo H, Talontsi F, Tane P, Kuiate J et al (2013) Chemical constituents, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Hypericum riparium (Guttiferae). Rec Nat Prod 7(1):65–68

Teles PW, Selva JC, Gómes CA (2007) Atividade acaricida dos óleos essencias de folias e frutos de Xylopia sericea sobre o ácaro rajado (Tetranychus urticae Koch). Quim Nova 30(4):838–841

Timóteo P, Karioti A, Leitão S, Vincieri F, Bilia A (2014) A validated HPLC method for the analysis of herbal teas from three chemotypes of Brazilian Lippia alba. Food Chem 175:366–373

Venzon M, Paula JT, Pallini A (2005) Controle Alternativo de Pragas e doenças. EPAMIG, Viçosa, p 894

Yoon R, Alenka H-R, Jayakumar P, Dehua L, Dusty P-B (1998) Epicuticular wax accumulation and fatty acid elongation activities are induced during leaf development of leeks. Plant Physiol 24:901–911

Zavoi S, Fetea F, Ranga F, Pop MR, Baciu A, Solacin C (2011) Comparative fingerprint and extraction yield of medicinal herb phenolic with hepatoprotective potential, as determined by UV-Vis and FT-MIR spectroscopy Notulae Botanicae. Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 39(2):82–89

Authors’ contributions

CBE and RD conceived the research. RL and NS conducted the experiments. NS, RD and CBE analyzed the data obtained. NS, RD and CBE wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work is derived from the research project INV-CIAS-1464, funded by the Research Vice-Rectory at Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, validity 2014. We also thank biologist Daniel Plazas for the collection and preparation of the plant material and extract.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical responsibilities of authors The authors whose names appear on the submission have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results. Finally, the authors report that the manuscript has not been submitted to more than one journal for simultaneous consideration, it has not been published previously, the data have not been fabricated or manipulated.

Ethical Approval (Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals) The ethics committee of the Universidad Militar Nueva Granada certified that after reviewing the ethical aspects required by the Experimental and Applied Acarology, the article meets the primary research with the ethical elements supported on ecological ethics of Jonas and Evolutionary Kieffer. Also, do not attentive to human values, or other living beings and instead contributes to the values that promote progressive development of society to acquire knowledge and skills needed to protect and improve the environment.

Informed consent The four authors of this manuscript accepted that the paper is submitted for publication in the Experimental and Applied Acarology, and report that this paper has not been published or accepted for publication in another journal, and it is not under consideration at another journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Numa, S., Rodríguez, L., Rodríguez, D. et al. Susceptibility of Tetranychus urticae Koch to an ethanol extract of Cnidoscolus aconitifolius leaves under laboratory conditions. SpringerPlus 4, 338 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1127-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1127-z