Abstract

Background and purpose

Malignant brain edema (MBE) occurring after mechanical thrombectomy (MT) in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) could lead to severe disability and mortality. We aimed to investigate the incidence, predictors, and clinical outcomes of MBE in patients with AIS after MT.

Methods

The clinical and imaging data of 155 patients with AIS of anterior circulation after MT were studied. Standard non-contrast CT was used to evaluate baseline imaging characteristics at admission. Clinical outcomes were measured using the 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score. Based on the follow-up CT scans performed within 72 h after MT, the patients were classified into MBE and non-MBE group. MBE was defined as a midline shift of ≥ 5 mm with signs of local brain swelling. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were used to analyze the relationship between MBE and clinical outcomes and identify the predictors that correlate with MBE.

Results

MBE was observed in 19.4% of the patients who underwent MT and was associated with a lower rate of favorable 90-day clinical outcomes. Significant differences were observed in both MBE and non-MBE groups: baseline Alberta Stroke Program Early CT (ASPECT) score, hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign (HMCAS), baseline signs of early infarct, angiographic favorable collaterals, number of retrieval attempts, and revascularization rate. Multivariate analysis indicated that low baseline ASPECT score, absent HMCAS, angiographic poor collaterals, more retrieval attempt count, and poor revascularization independently influenced the occurrence of MBE in AIS patients with anterior circulation after MT.

Conclusion

MBE was associated with a lower rate of favorable 90-day clinical outcomes. Low baseline ASPECT score, absent HMCAS, angiographic poor collaterals, more retrieval attempt count and poor revascularization were independently associated with MBE after MT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS), caused by large vessel occlusion (LVO), is a common cerebrovascular disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. About 70–80% cases of large vessel occlusion stroke (LVOS) occured in the anterior circulation [1]. Mechanical thrombectomy (MT) was accepted as the standard care for patients with anterior circulation LVOS after findings from five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were reported in 2015 [2]. Although MT could improve the short-term recanalization rate, patients were still at risk of developing malignant brain edema (MBE), which was a life-threatening complication. Due to the rigidity of the skull, MBE concomitant with intracranial hypertension may not only cause fatal herniation and decrease cerebral perfusion pressure but also compromise cerebral oxygenation and neurological deterioration [3, 4]. Early treatment could help improve the outcomes. Nevertheless, studies on the effect of MT concerning the incidence and predictive factors of MBE were inadequate.

MBE has been associated with several risk factors, such as younger age, higher National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, and larger parenchymal hypoattenuation on CT [4]. Previous studies identified that the hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign (HMCAS) was associated with increased stroke severity at presentation and worse long-term outcomes [5, 6]. However, evidence on the value of HMCAS in predicting the development of MBE and outcomes of MT is limited. Few studies have explored an objective HMCAS measure in patients who undergo MT. Moreover, the interrater reliability of subjective assessment by neurologists remains poor.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the incidence, predictors, and clinical outcomes of MBE in AIS patients with anterior circulation large vessel occlusion after MT.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Institutional Review Board of the General Hospital of Northern Theatre Command approved the study. All hospitalized patients with anterior circulation LVO ischemic stroke who underwent MT during the period from June 2016 to December 2021 were recruited. Indications for MT followed the most recent treatment guidelines at the time of patient inclusion [7]. Baseline clinical information, imaging data, and periprocedural data of patients were collected and reviewed.

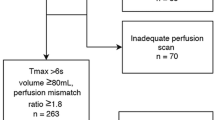

The inclusion criteria included: (1) adults aged at least 18 years; (2) anterior circulation LVOS comprising middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion (M1 or M2 segments) and terminal internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusion confirmed by digital subtraction angiography (DSA) prior to MT; (3) baseline Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECT) score ≥ 6, baseline NIHSS score ≥ 6, and pre-stroke mRS score ≤ 2; and (4) time from onset to puncture (OTP) ≤ 24 h. The exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with parenchymal hemorrhage (PH) after MT; (2) patients without complete clinical and imaging data. The flowchart of patient enrolment is shown in Fig. 1.

Clinical information collection and assessment

The baseline characteristics of the study participants were collected from the medical records. They included demographic data (age and sex), medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and past history of stroke), habits and customs (smoking and alcohol use), TOAST, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment, radiographic data, and duration from stroke onset to imaging. The periprocedural parameters included occluded vessel region, intravenous thrombolytic therapy, OTP, remedial measures (balloon dilatation and stent implantation), the number of retrieval attempts, and revascularization of occluded vessels. A certified stroke neurologist assessed the severity of the neurological deficit and status of each patient using the NIHSS during admission at the emergency department.

Image acquisition and analysis

Standard non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) was performed using a US GE Discovery CT 750 HD scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). It was initially performed for all participants using the following parameters: 100 kV, 120 mA, 40 mm collimator width, 25 cm field of view, 5 mm layer thickness, and 5 mm layer spacing. Participants were placed in the supine position with their upper limbs lying flat on both sides of their bodies and head slightly inclined.

Image review was independently performed on a wide-screen high-resolution monitor with an adequate window and level setting. The imaging characteristics of all participants were evaluated by two experienced neuroimaging physicians with no prior knowledge of participants’ clinical information and conventional angiographic findings. In the case of a difference in opinion after assessment, an agreement was reached through consultation. The baseline ASPECT score, HMCAS, and signs of early infarct were assessed on the first NCCT at admission (time from onset to first NCCT ≤ 24 h). MBE was evaluated on NCCT within 72 h after MT. We used the standard ASPECT score to determine stroke burden (range from 0 to 10). A score of zero indicated diffuse cerebral infarction in the region of MCA blood supply, and a score of 10 indicated no new cerebral infarction. To objectively evaluate HMCAS, elliptical regions of interest were placed at MCA on both sides, and measure the attenuation of Hounsfield unit (HU). HMCAS was defined as the MCA attenuation > 43 HU and > 1.2 times of normal contralateral vascular density [8]. Baseline signs of early infarct refer to the observation of any of the following conditions: hypoattenuation in less than one-third of the middle cerebral artery area, blurred lenticular nucleus, disappearance of basal ganglia contour, disappearance of insular ribbon, blurring of sylvian fissure, or disappearance of cortical sulcus [9]. PH was defined as blood clots of the infarcted area with some slight space-occupying effect according to the ECASS (European Collaborative Acute Stroke Study) classification [10]. In previous studies, MBE was present if (1) > 50% of the MCA area had parenchymal hypodensity with signs of local brain swelling, such as disappearance of the sulci and gyri and compression of the lateral ventricle; and (2) midline shift of ≥ 5 mm was present at the septum pellucidum or pineal gland with obliteration of the basal cisterns [11] (Fig. 2). The initial angiogram before the treatment allowed for collaterals assessment based on the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology/Society of Interventional Radiology [12]. The score ≥ 3 was defined as favorable collateral status.

Outcome indicators

Intracranial arterial recanalization status was determined by DSA immediately after MT using the modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (mTICI) grade. Successful recanalization was defined as an mTICI score of 2b to 3.

Clinical outcomes were measured using mRS at 90 days after onset. A favorable clinical outcome was defined as an mRS of 0–2. An mRS of 2 indicated slight disability (inability to perform all previous activities but cater for themselves without assistance), whereas an mRS ≥ 3 was considered a poor clinical outcome.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 22.6; IBM, Armonk, New York). Quantitative variables (age, NIHSS score at admission, baseline ASPECT score, time from stroke onset to imaging and OTP, the number of retrieval attempts) were reported as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables (sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, past history of stroke, atrial fibrillation, smoking, alcohol use, HMCAS, signs of early infarct, TOAST classification, occluded vessel region, intravenous thrombolytic therapy, angiographic favorable collaterals, balloon dilatation, stent implantation, and revascularization) were presented as frequencies and percentages. Normality of distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Student’s t test was used to compare two groups of normally distributed continuous data, whereas the Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two groups of non-normally distributed continuous data. Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test was used to compare two groups of categorical data. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were used to analyze the relationship between MBE and clinical outcomes and identify the predictors of MBE. Factors with P ≤ 0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression as independent variables for multivariate analysis. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demography data of patients

Two-hundred and eighty patients with LVO in the anterior circulation and had undergone MT were included in this study. Among these participants, 10 cases had preoperative ASPECT score < 6, 4 cases had NIHSS score at admission < 6, 4 cases had non-terminal occlusion of ICA, 58 cases had parenchymal hematoma, 49 cases lacked complete clinical and imaging data. Finally, 155 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). The median age of the participants was 64 (IQR, 54–72) years, and 102 (65.8%) participants were male. 79 (51.0%) participants presented with HMCAS, and 81 (52.3%) participants presented with baseline signs of early infarct. Participants’ baseline ASPECT score was 8 (IQR, 8–10), and NIHSS score at admission was 14 (IQR, 11–17). 41 (26.5%) participants received MT and intravenous thrombolysis, and 130 (83.9%) participants were revascularized successfully. 68 (43.9%) participants had favorable 90-day clinical outcomes (mRS ≤ 2) (Table 1).

Factors associated with MBE

MBE was observed in 30 (19.4%) participants. The MBE group recorded a lower baseline ASPECT score than the non-MBE group (8 [6–9] vs 9 [8–10], P < 0.001). The MBE group had a lower HMCAS (20.0% vs 58.4%, P < 0.001), angiographic favorable collateral (16.7% vs 39.2%, P = 0.020) and revascularization rate (50.0% vs 92.0%, P < 0.001) than the non-MBE group. Additionally, the MBE group recorded higher baseline signs of early infarct (80.0% vs 45.6%, P = 0.001) and greater number of retrieval attempts (2 [1–4] vs 1 [1, 2], P = 0.018) than the non-MBE group.

No between-group differences were observed in age, sex, medical history, baseline NIHSS score, TOAST classification, intravenous thrombolytic therapy, stent implantation, and remedial measures including balloon dilatation. Additionally, no differences were observed in the occluded vessel region, time from onset of stroke to imaging, OTP, and medical history between both groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Binary logistic regression analysis showed that low baseline ASPECT score (OR = 0.429, 95% CI 0.238–0.773, P = 0.005), absent HMCAS (OR = 4.576, 95% CI 1.352–15.485, P = 0.014), angiographic poor collaterals (OR = 5.346, 95% CI 1.322–21.628, P = 0.019), more retrieval attempt count (OR = 1.877, 95% CI 1.016–3.465, P = 0.044), and poor revascularization (mTICI < 2b) (OR = 11.937, 95% CI 2.932–48.602, P = 0.001) were independently associated with MBE after MT in patients with AIS caused by an anterior circulation LVO. Adjustment for the following confounding factors was performed before the analysis: NIHSS score at admission, baseline ASPECT score, absent HMCAS, baseline signs of early infarct, angiographic poor collaterals, poor revascularization, and number of retrieval attempts (Table 2).

MBE and clinical outcomes

In the univariate analysis, patients without MBE had better favorable 90-day clinical outcomes than patients with MBE (51.2% vs 13.3%, P < 0.001). Binary logistic regression analysis showed that patients with MBE (OR = 0.284, 95% CI 0.083–0.969, P = 0.044) were inversely associated with favorable 90-day clinical outcomes after adjusting for the NIHSS score at admission, angiographic favorable collaterals, number of retrieval attempts, revascularization, and presence of MBE (Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

This study investigated the incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes of MBE in patients with AIS due to anterior circulation LVO and had undergone MT. The incidence of MBE was 19.4% in our study. MBE was associated with poor clinical outcomes (mRS ≥ 3). Participants with absent HMCAS were more likely to develop MBE after MT. Moreover, low baseline ASPECT score, angiographic poor collaterals, more retrieval attempt count and poor revascularization (mTICI < 2b) were significant predictors of malignant progression.

A large multi-center study on a cohort of patients with AIS and LVO of anterior circulation showed that the MBE occurrence rates differed significantly among treatment groups. The treatment groups—no treatment, IV-TPA, and EVT—recorded rates of 50.1%, 32.2%, and 23.8%, respectively [13]. The results showed that intravascular therapy can effectively reduce the incidence of MBE. According to our results, the occurrence rate of MBE in MT-treated patients with AIS due to anterior circulation LVO was 19.4%. MBE was associated with poor prognosis. Therefore, early identification of high-risk patients with MBE after MT is necessary deciding the treatment options, which can guide clinicians to initiate life-saving treatment early to improve the prognosis of patients' neurological function.

A hyperdense segment of vessels, which represented direct imaging of the intravascular thrombus, was detected on NCCT in patients with AIS. Although this segment could be observed in any vessel, it was mostly observed in MCA as HMCAS [14]. HMCAS was found in only 33–50% of angiographically confirmed cases of thrombosis [14]. The HMCAS was observed in 51.0% (79/155) patients in our study, which may be related to the time of the CT scan after onset of cerebral infarction, thickness of CT layer, and composition of thrombosis. The HMCAS on head CT may be observed as early as within 90 min after ictus and disappears within few days [15, 16]. Manelfe et al. [17] found that in 107 patients with present HMCAS within 6 h, 55% of patients showed present HMCAS in the second CT scan within 12–24 h, whereas only 26% of patients showed present HMCAS in the third CT scan within 6–8 days. AIS thrombi consist of three components: red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and fibrin/other components. According to previous studies, the presence and density of HMCAS were associated with RBC-dominant thrombi, which represented the concentration of hemoglobin, whereas the absence of HMCAS was indicative of fibrin/platelet-rich thrombi [18].

Our results showed that absent HMCAS was related to the occurrence of MBE (Table 2). We speculate that the patients were more prone to MBE in the absence of HMCAS due to the composition of the embolus. Thrombus components have different characteristics, such as stiffness, stickiness, deformability, and mechanical friction. All these characteristics can influence the success rate of recanalization. RBC-rich thrombi had a lower coefficient of friction, lower stiffness, potentially higher deformability, and better integration ability of stent strut into the thrombus than fibrin/platelet-rich thrombi [18]. The degree of clot integration into the thrombectomy device was decreased in fibrin-rich thrombi. The fibrin strands could increase clot rigidity and influence the thrombus coefficient of friction and level of physical compression, making these thrombi more resistant to mechanical removal.

Previous studies found that cardioembolic thrombi were characterized by higher amounts of RBCs and lower amounts of fibrin than large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) thrombi [18]. Kim et al. [19] found that aortic atherosclerosis was more common in patients with absent HMCAS. Therefore, we speculate that absent HMCAS on NCCT before MT may indicate in situ thrombotic occlusion caused by large atherosclerosis and poor vascular recanalization rate. We thought that radiological imaging could predictably characterize thrombus composition and determine thrombus location and size. Current imaging modalities could not only differentiate between RBC-dominant and fibrin/platelet-dominant thrombi but also guide clinical decisions, such as selection of thrombus-specific retrieval protocols or device technologies. Future studies will determine the link between radiological signs and thrombus composition and develop pre-treatment decision-making strategies to improve the success rates of first-pass recanalization.

Our results showed that more retrieval attempt count were associated with poor functional outcomes. More retrieval attempt count increases the risk of vascular injury and destruction of the blood–brain barrier due to MBE [20]. Available evidence informing the ability of retrieval attempts number to reliably predict the development of MBE are insufficient. Our results showed that the number of retrieval attempts was a potential biomarker for predicting MBE after MT.

Additionally, we found that low ASPECT score was an independent factor associated with MBE, which was consistent with findings from previous studies [21,22,23]. The ASPECT score was a scoring system that can identify the extent of the initial infarct on CT after a stroke. Although the detection methods of ischemic size in these studies were different (multiphase perfusion CT, magnetic resonance diffusion weighted imaging, and NCCT), all the results showed that the ischemic size at baseline was related to MBE.

Previous studies have shown that the range of the pial collateral was related to the infarct growth and final infarct volume, and the distribution of undesirable collateral was closely related to the severity of hypoperfusion [24,25,26], in line with our findings.

In acute LVOS, early restoration of blood flow to ischemic brain tissues had repeatedly been shown to improve clinical outcomes. However, several studies have suggested that revascularization may lead to secondary injury [27, 28]. After cerebral vascular recanalization with intra-arterial thrombectomy, occluded vascular recanalization causes more water to pass through the damaged blood–brain barrier. This aggravates angiogenic edema, further aggravates the destruction of the blood–brain barrier, triggers secondary cascade injury reaction, and leads to neuronal death. Additionally, the results of previous animal experiments showed that recanalization may aggravate the development of brain edema [29,30,31]. Contrarily, other studies had shown that successful recanalization could reduce the development of early and late brain edema [32,33,34]. The recovery of cerebral blood flow may save brain tissues by saving ischemic penumbra, preventing the growth of infarct size, and limiting edema-related tissue damage [32]. Therefore, the occurrence degree and injury outcomes of edema might depend on the balance between benefit of vascular recanalization and reperfusion brain edema injury.

Findings from our study indicated that successful recanalization reduced the occurrence of MBE within 72 h. Post-hoc analysis of the MR-CLEAN cohort showed that [34] successful recanalization was associated with a reduced likelihood of midline displacement on a 24-h follow-up CT. Thorén et al. [33] found that successful recanalization of blood vessels reduced the occurrence of moderate-to-severe brain edema within 22–36 h. Huang et al. [11] evaluated the midline shift on the follow-up images within 72 h, and the results showed that the vascular recanalization rate in the MBE group was significantly lower than that in the non-MBE group, which is consistent with findings from our study. Irvine et al. [32] reported that reperfusion was associated with smaller midline shift and lower swelling volume when MRI was taken during 3–8 days of follow-up. On all accounts, although the destruction of the blood–brain barrier may be exacerbated after vascular recanalization, this treatment method may reduce the risk and degree of MBE.

This study had some limitations. First, all patients were recruited from a single institution, limiting the sample size available and generalizability of the outcomes. Second, the definition and evaluation of brain edema were relatively simple (imaging-based NCCT). Third, we excluded patients with PH, consistent with prior studies [11, 34,35,36], which will lead to some patients with coexisting edema and hemorrhage were also exclude. Finally, due to lack of CTP or DWI examinations in certain patients before MT, cerebrovascular reserve calculation in CT/MR perfusion and DWI core volume were not considered in this study. Further multi-center prospective large population studies, considering more clinical risk factors, are needed to confirm our results.

Conclusion

The incidence of MBE after MT was 19.4% in this study. MBE was associated with a lower rate of favorable 90-day clinical outcomes in patients with AIS who had an anterior circulation LVO after MT. Absent HMCAS, low baseline ASPECT score, angiographic poor collaterals, more retrieval attempt count and poor revascularization (mTICI < 2b) were independently associated with the occurrence of MBE after MT.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to intellectual property rights, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MBE:

-

Malignant brain edema

- MT:

-

Mechanical thrombectomy

- AIS:

-

Acute ischemic stroke

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin Scale

- ASPECT:

-

Alberta Stroke Program Early CT

- LVO:

-

Large vessel occlusion

- LVOS:

-

Large vessel occlusion stroke

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- NIHSS:

-

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- HMCAS:

-

Hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

- ICA:

-

Internal carotid artery

- DSA:

-

Digital subtraction angiography

- OTP:

-

Time from onset to puncture

- PH:

-

Parenchymal hemorrhage

- ECASS:

-

European Collaborative Acute Stroke Study

- TOAST:

-

Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

- NCCT:

-

Non-contrast computed tomography

- HU:

-

Hounsfield unit

- mTICI:

-

Modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction

- RBCs:

-

Red blood cells

- WBCs:

-

White blood cells

- LAA:

-

Large-artery atherosclerosis

References

Rennert RC, Wali AR, Steinberg JA, Santiago-Dieppa DR, Olson SE, Pannell JS, et al. Epidemiology, natural history, and clinical presentation of large vessel ischemic stroke. Neurosurgery. 2019;85(1):S4–8.

Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387(10029):1723–31.

Jha RM, Kochanek PM, Simard JM. Pathophysiology and treatment of cerebral edema in traumatic brain injury. Neuropharmacology. 2019;145(Pt B):230–46.

Wu S, Yuan R, Wang Y, Wei C, Zhang S, Yang X, et al. Early prediction of malignant brain edema after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2018;49(12):2918–27.

Sun H, Liu Y, Gong P, Zhang S, Zhou F, Zhou J. Intravenous thrombolysis for ischemic stroke with hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;141(3):193–201.

Mair G, von Kummer R, Morris Z, von Heijne A, Bradey N, Cala L, et al. Effect of alteplase on the CT hyperdense artery sign and outcome after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2016;86(2):118–25.

Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344–418.

Koo CK, Teasdale E, Muir KW. What constitutes a true hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign? Cerebrovasc Dis (Basel, Switzerland). 2000;10(6):419–23.

Strbian D, Meretoja A, Putaala J, Kaste M, Tatlisumak T. Cerebral edema in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(7):529–34.

Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Davalos A, Meier D, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke. (ECASS II) Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet (London, England). 1998;352(9136):1245–51.

Huang X, Yang Q, Shi X, Xu X, Ge L, Ding X, et al. Predictors of malignant brain edema after mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(10):994–8.

Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, Tomsick T, Connors B, Barr J, et al. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(8):e109–37.

Fuhrer H, Schönenberger S, Niesen WD, Seide S, Meyne J, Gerner ST, et al. Endovascular stroke treatment’s impact on malignant type of edema (ESTIMATE). J Neurol. 2019;266(1):223–31.

Chrzan R, Gleń A, Urbanik A. Hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign as the only radiological manifestation of hyperacute ischemic stroke in computed tomography. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2017;51(1):33–7.

Mullins ME. The hyperdense cerebral artery sign on head CT scan. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26(6):394–403.

Leys D, Pruvo JP, Godefroy O, Rondepierre P, Leclerc X. Prevalence and significance of hyperdense middle cerebral artery in acute stroke. Stroke. 1992;23(3):317–24.

Manelfe C, Larrue V, von Kummer R, Bozzao L, Ringleb P, Bastianello S, et al. Association of hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign with clinical outcome in patients treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 1999;30(4):769–72.

Staessens S, François O, Brinjikji W, Doyle KM, Vanacker P, Andersson T, et al. Studying stroke thrombus composition after thrombectomy: what can we learn? Stroke. 2021;52(11):3718–27.

Kim SK, Baek BH, Lee YY, Yoon W. Clinical implications of CT hyperdense artery sign in patients with acute middle cerebral artery occlusion in the era of modern mechanical thrombectomy. J Neurol. 2017;264(12):2450–6.

Seker F, Pfaff J, Wolf M, Ringleb PA, Nagel S, Schönenberger S, et al. Correlation of thrombectomy maneuver count with recanalization success and clinical outcome in patients with ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(7):1368–71.

Huang X, Chen C, Wang H, Cai Q, Li Z, Xu J, et al. The ACORNS grading scale: a novel tool for the prediction of malignant brain edema after endovascular thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnis-2022-019404.

Jiang QM, Yu S, Dong XF, Wang HS, Hou J, Huang ZC, et al. Predictors and dynamic nomogram to determine the individual risk of malignant brain edema after endovascular thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurol (Seoul, Korea). 2022;18(3):298–307.

Guo W, Xu J, Zhao W, Zhang M, Ma J, Chen J, et al. A nomogram for predicting malignant cerebral artery infarction in the modern thrombectomy era. Front Neurol. 2022;13: 934051.

Saber H, Liebeskind DS. Infarct progression in the early and late phases of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2021;97(20 Suppl 2):S60–7.

Federau C, Wintermark M, Christensen S, Mlynash M, Marcellus DG, Zhu G, et al. Collateral blood flow measurement with intravoxel incoherent motion perfusion imaging in hyperacute brain stroke. Neurology. 2019;92(21):e2462–71.

Kim BJ, Chung JW, Park HK, Kim JY, Yang MH, Han MK, et al. CT angiography of collateral vessels and outcomes in endovascular-treated acute ischemic stroke patients. J Clin Neurol (Seoul, Korea). 2017;13(2):121–8.

Suroto NS, Fauzi AA, Christi AY, Simanjuntak KAT, Budiono PS. Case of malignant brain edema despite successful recanalization after mechanical thrombectomy for anterior circulation stroke. Surg Neurol Int. 2023;14:111.

Terlecki P, Przywara S, Terlecki K, Janczak D, Antkiewicz M, Zubilewicz T. Effect of reconstructive procedures of the extracranial segment of the carotid arteries on damage to the blood-brain barrier. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):6210.

Pillai DR, Dittmar MS, Baldaranov D, Heidemann RM, Henning EC, Schuierer G, et al. Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats–a 3 T MRI study on biphasic blood-brain barrier opening and the dynamics of edema formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(11):1846–55.

Bell BA, Symon L, Branston NM. CBF and time thresholds for the formation of ischemic cerebral edema, and effect of reperfusion in baboons. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(1):31–41.

Gartshore G, Patterson J, Macrae IM. Influence of ischemia and reperfusion on the course of brain tissue swelling and blood-brain barrier permeability in a rodent model of transient focal cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol. 1997;147(2):353–60.

Irvine HJ, Ostwaldt AC, Bevers MB, Dixon S, Battey TW, Campbell BC, et al. Reperfusion after ischemic stroke is associated with reduced brain edema. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38(10):1807–17.

Thorén M, Dixit A, Escudero-Martínez I, Gdovinová Z, Klecka L, Rand VM, et al. Effect of recanalization on cerebral edema in ischemic stroke treated with thrombolysis and/or endovascular therapy. Stroke. 2020;51(1):216–23.

Kimberly WT, Dutra BG, Boers AMM, Alves H, Berkhemer OA, van den Berg L, et al. Association of reperfusion with brain edema in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a secondary analysis of the MR CLEAN trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(4):453–61.

Battey TW, Karki M, Singhal AB, Wu O, Sadaghiani S, Campbell BC, et al. Brain edema predicts outcome after nonlacunar ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3643–8.

Yoo AJ, Sheth KN, Kimberly WT, Chaudhry ZA, Elm JJ, Jacobson S, et al. Validating imaging biomarkers of cerebral edema in patients with severe ischemic stroke. J stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(6):742–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Jingshu Chen for helping in collecting clinical data. Dr. Zhihua Xu provided editorial assistance on the final version of the manuscript, limited to editing and formatting.

Funding

This study was funded by Project of Applied Basic Research Combine Program of Liaoning Province (Grant numbers, 2022JH2/101500024), Project of Key Research and the Development Program of Liaoning Province, China (Grant numbers, 2020JH2/10300119), Project of Natural Science Foundation of Shenyang (Grant numbers, 20-205-4-044), Project of Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant numbers, 201602768) and Project of Scientific Research Foundation for the PhD of Liaoning Province (Grant numbers, 2019-BS-267).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. LZ, JL, and YD conceived the project idea. BY provided critical suggestions for the experiments design. LZ, JL, WL, XW, MZ, HS and LS collected the imaging and clinical data. LZ, JL, HS, and YD provided the imaging analysis. LZ, JL, YD, and BY wrote the paper. YD supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of General Hospital of Northern Theatre Command (Approval number: Y-2020-012).

Consent for publication

All authors gave consent for the publication.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Li, J., Yang, B. et al. The risk and outcome of malignant brain edema in post-mechanical thrombectomy: acute ischemic stroke by anterior circulation occlusion. Eur J Med Res 28, 435 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01414-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01414-x