Abstract

Background

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a major burden for hospitals globally. However, in the Netherlands, the MRSA prevalence is relatively low due to the ‘search and destroy’ policy. Routine multiple-locus variable-number of tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) of MRSA isolates supports outbreak detection. However, whole genome multiple locus sequence typing (wgMLST) is superior to MLVA in identifying (pseudo-)outbreaks with MRSA. The present study describes a pseudo-outbreak of MRSA at the bacteriology laboratory of a large Dutch teaching hospital.

Methods

All staff members of the bacteriology laboratory of the Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital were screened for MRSA carriage, after a laboratory contamination with MRSA was suspected. Clonal relatedness between the index isolate and the MRSA isolates from laboratory staff members and all previous MRSA isolates from the Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital with the same MLVA-type as the index case was examined based on wgMLST using whole genome sequencing.

Results

One of the staff members was identified as the probable source of the laboratory contamination, because of carriage of a MRSA possessing the same MLVA-type as the index case. Eleven other isolates with the same molecular characteristics were found in the database, of which seven were retrospectively suspected of contamination. Clonal relatedness was found between ten isolates, including the isolate found in the staff member and the MRSA found in the index patient with a maximum of eleven alleles difference. All isolates were epidemiologically linked through the laboratory staff member, who had worked on all these cultures.

Conclusions

The present study describes a MRSA pseudo-outbreak over a 2.5-year period due to laboratory contamination caused by a MRSA carrying laboratory staff member involving nine patients. In case of unexpected bacteriological findings, the possibility of a laboratory contamination should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen and an important cause of nosocomial and community-acquired infections [1]. Since the 1960s, methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains have emerged. These strains harbor a mecA gene making them resistant to almost all β-lactam antibiotics [2, 3]. In the Netherlands, the prevalence of MRSA carriage is low, ranging from 0.03% to 0.17% [4]. Despite this low MRSA prevalence in the Netherlands, nosocomial outbreaks do occur [5]. To detect the source and route of transmission in hospital outbreaks, epidemiological investigation can be combined with molecular typing of the bacterial isolates. Molecular typing of S. aureus can be done using Staphylococcal protein A (spa) typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multiple loci variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA), or whole genome multi-locus sequence typing (wgMLST) [6]. The latter has the highest discriminatory power due to the many alleles included in the analysis to identify or dismiss clonal relatedness.

In March 2019, an unexpected MRSA finding in a patient led to the suspicion of a laboratory contamination. This patient had a S. aureus infection of a prosthetic joint of the knee. The infection was diagnosed based on methicillin sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) in five of eight tissue cultures of the knee. Unexpectedly, MRSA colonies were found in one of the eight cultures. To verify this finding, all original tissue samples were cultured again and swabs originating from the patient’s anterior nares, throat and perineum were cultured to test for MRSA carriage. In none of these cultures, MRSA was found, suggesting that the previously cultured MRSA was a laboratory contamination rather than an actual MRSA infection. For this reason, contact investigation was not performed for the patient’s contacts and infection control measures were lifted. Multiple studies have described laboratory contamination of clinical specimens though various causes [8,9,10]. The objective of the present study was to determine the source and the extent of this MRSA contamination. Whole genome multiple locus sequence typing (wgMLST) was performed to identify a pseudo-outbreak of MRSA due to laboratory contamination.

Methods

Setting and routine microbiology methods regarding MRSA

Setting

The Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital, Tilburg, the Netherlands is a teaching hospital with 796 beds. Around 85 new cases of MRSA carriage or infection are identified each year. Upon hospital admission, all patients are screened for risk factors for MRSA carriage using a questionnaire. Such risk factors are recent hospital admission abroad, professional contact with livestock, intensive contact with a MRSA carrier or a stay in a refugee center in the last two months [11]. In case of a high or intermediate risk, swabs are taken to test for MRSA carriage [11]. This screening is part of the ‘search and destroy’ policy in the Netherlands and is followed by strict isolation and treatment of MRSA carriers [11, 12].

Routine microbiology methods regarding MRSA

For MRSA carriage screening swabs of the anterior nares, throat, perineum and, if present, catheters, drains and cutaneous lesions were collected using eSwab medium (Copan, Murrieta, USA) [12]. The swabs were inoculated on a chromogenic MRSA2 Brilliance agar (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK), on which MRSA isolates appear as blue colonies after overnight incubation at 35 ± 1 °C, and on a blood agar plate as growth control. The remaining eSwab medium was added to Mueller Hinton Broth (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, USA) supplemented with 6.5% sodium chloride. After overnight incubation at 35 ± 1 °C, the broth was inoculated on a chromogenic MRSA2 Brilliance agar. Species determination of presumptive MRSA colonies was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Leipzig Germany). Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed of S. aureus isolates using either BD Phoenix 100 system (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, USA) or disc diffusion (BD Diagnostics, Sparks, USA) according to EUCAST [13]. An in-house real-time PCR was performed on isolates with a cefoxitin MIC values > 4 mg/L or cefoxitin (30 μg) disc diffusion diameter < 22 mm to confirm the MRSA identification, detecting the Sa442 DNA fragment [14], S. aureus nuclease (nuc) [15], Panton-Valentine leukocidine (PVL) [16], and methicillin resistance genes MecA and MecC [17, 18]. Additionally, in selected samples (e.g., in case of limited patient isolation capacity) direct molecular screening for MRSA presence can be performed using the Xpert® MRSA NxG detection kit (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, USA). For each patient where MRSA was cultured, the isolate was sent to the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) for further genotyping by MLVA as described by Schouls et al. [19].

Source and extent of laboratory contamination

Source of laboratory contamination

Laboratory staff members were screened for MRSA carriage by sampling of the anterior nares, throat and perineum. These samples were cultured as described above.

Extend of laboratory contamination

The laboratory data system was searched for all MRSA isolates cultured in the Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital from January 2008 until May 2019 with the same MLVA-type as the index MRSA isolate. For each of the detected MRSA isolates with an identical MLVA-type, the likelihood of (laboratory) contamination (likely or unlikely) was determined. Contamination with a MRSA isolate was deemed likely if the MRSA isolate was only cultured once and not in any other sample of the same patient.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and wgMLST

The MRSA index isolate, the MRSA isolates from the laboratory staff members, the MRSA isolates detected in the laboratory data system and the control strain ATCC43300 were selected for WGS. WGS was performed using Nextera XT chemistry on a Miseq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). After error-correction and de novo genome assembly on CLC genomics workbench 20.0.4 (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), the number of allelic differences between the MRSA isolates was determined using the wgMLST tools of Ridom SeqSphere + version 7.7.5 (Ridom GmbH, Munich, Germany). A total of 2574 alleles were included in the pairwise comparison, in which missing values were ignored. For data visualization, a neighbor-joining tree was created. A maximum allelic difference of 24 alleles was used to identify clusters [20].

Results

Source of laboratory contamination

All 23 laboratory staff members working in the bacteriology department were screened for MRSA carriage. Three cultures from two staff members were positive for MRSA. Strain Msta02 was cultured from the perineum of technician 1 and belonged to the MLVA type MT0398-MC0398. Strain Msta03 was cultured from the anterior nares and throat of technician 2 and belonged to MLVA-type MT0489-MC0022, identical to the MLVA-type of the index MRSA isolate Msta01 (Table 1).

Extent of laboratory contamination

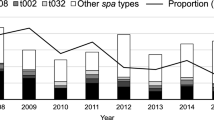

Between January 2008 and May 2019, MLVA-typing was performed on 1037 MRSA isolates. Among those, 12 isolates belonged to the MLVA-type MT0489-MC0022 (including Msta01) and carried a MecA gene. All 12 isolates were found between November 2016 and March 2019 (Table 1) (Fig. 2). Seven of the twelve isolates were suspect for contamination based on the selection criteria (MRSA detected in only 1 sample), namely Msta01 (index patient), Msta06, Msta09, Msta10, Msta11, Msta13, and Msta14 (Table 1). All these isolates were epidemiologically linked through the laboratory staff member Technician 2, who worked on all these cultures. Msta04, Msta05, Msta07, and Msta08 were not suspect for laboratory contamination, since these isolates were found in multiple samples (Table 1). There was no sufficient data to determine the likelihood of contamination of Msta12. There is an epidemiological relationship between the patient C and E since patient E is the partner of patient C. No epidemiological link was detected between any of the other patients.

Whole genome sequencing and wgMLST

Whole genome sequence data was generated for all isolates described in Table 1 and the ATCC43300 reference strain. All assembled genomes met the quality criteria (Additional file 1: Table S1). WgMLST revealed two clusters (Fig. 1). The cluster indicated in red in Fig. 1 consists of Msta03, detected in technician 2, Msta01, Msta05, Msta06, Msta07, Msta09, Msta10, Msta11, Msta13 and Msta14. The number of alleles difference between these 10 isolates ranged from 0 to 11 alleles, indicating that they belong to the same genetic cluster (Additional file 2: Table S2). Within this cluster, 8 isolates (Msta01, Msta03, Msta06, Msta09, Msta10, Msta11, Msta13 and Msta14) were suspected of laboratory contamination. However, Msta05 and Msta07 were not suspected of laboratory contamination. The timeline of the identified pseudo-outbreak cluster revealed that, chronologically, the outbreak starts with Msta05 (Fig. 2). The second cluster is indicated in blue in Fig. 1 and consists of Msta04, Msta08 and Msta12 with a difference ranging from 16 to 19 alleles (Additional file 2: Table S2). None of these isolates was suspected of laboratory contamination and epidemiological links were absent in this cluster. The isolates in the second cluster differed at least 275 alleles from the first identified cluster containing both Msta01 (index isolate) and Msta03 found in technician 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of MRSA isolates based on wgMLST. The horizontal distance corresponds to the absolute number of allelic differences between isolates. Details of the isolates are depicted in Table 1. The pseudo-outbreak cluster is indicated in red with a maximum allelic difference of 11 alleles. The isolates in blue do have the same MLVA characteristics, but form a separate cluster. Green indicates the MRSA isolates with other MLVA characteristics, including control strain ATCC43300. The number of allelic differences (or range) between clusters are indicated in black and within clusters in red or blue corresponding to the cluster color

Discussion

This report describes a MRSA pseudo-outbreak due to a laboratory contamination by a MRSA carrying laboratory staff member involving nine patients over a period of 2.5 years. The pseudo-outbreak cluster was identified by wgMLST and had a maximum allelic difference of 11 alleles. A previous wgMLST cluster analysis study found a relatedness threshold of < 24 alleles for S. aureus [20]. However, all difference > 5 alleles should be interpreted with caution and in relation to the presence or absence of an epidemiological link [21]. Moreover, the determination of the relatedness threshold of wgMLST is complicated by the evolution rate of active growing of isolates, which is 1 mutation per 6 weeks in the case of MRSA [22]. In the present study, two clusters were identified. One is the pseudo-outbreak cluster in which the most divergent samples within the cluster were isolated 17 months apart, which could explain the increased number of allelic differences. The two isolates isolated in the last three months of the pseudo-outbreak differ only 1 allele from the isolate found in the staff member. Furthermore, all isolates in this cluster had an epidemiological link through the MRSA carrying staff member. Based on wgMLST and their epidemiological link, it is likely that all nine MRSA isolates do belong to the pseudo-outbreak. The other cluster consisting of three MRSA isolates without an epidemiological link, are not part of an (pseudo-)outbreak based on this analysis. Although these isolates had the same MLVA-typing, based on wgMLST these three isolates were clearly distinct from the isolates belonging to the pseudo-outbreak cluster. This illustrates the added value of wgMLST compared to MLVA-typing.

Chronologically, the first isolate of the pseudo-outbreak cluster was not suspected of contamination, since the MRSA carriage in this patient was confirmed by multiple cultures making laboratory contamination highly unlikely. The laboratory staff member may have been infected with Msta03 during culturing of Msta05 in January 2017. It is only after January 2017 that we observed an increase of MRSA isolates in the Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital with MLVA MT0489-MC0022. The only MRSA isolate with the same MLVA-type isolated before 2017 (Msta04) did not belong to the same cluster according to the WgMLST analysis. The MRSA carrying staff member had no risk factors for MRSA carriage. Although we have no definite proof, it seems most likely that the laboratory staff member was infected during laboratory activities. Infections acquired during laboratory work with various other bacteria have been described, but MRSA is not recognized as a pathogen that presents a risk of laboratory infection [23]. An increased incidence for Staphylococcus aureus carriage was found in a Dutch cross-sectional study among laboratory staff members, but observed a MRSA prevalence comparable to that of the general population [24]. In the present study, two of the 23 laboratory staff members working at the bacteriology department were MRSA carriers (8.9%) (unrelated strains). This is more than could be expected based on the general Dutch population where the MRSA prevalence is < 1% [4, 12]. However, more research is needed to determine whether there is an increased risk for MRSA carriage among laboratory staff members.

Although pseudo-outbreaks due to laboratory contamination of clinical specimens have been reported [7,8,9,10], to the best of our knowledge, no pseudo-outbreak due to MRSA carriage of a laboratory staff member has been described before. This may be due to reporting bias, but also due to a lack of awareness recognizing such pseudo-outbreaks. At the time the current pseudo-outbreak due to laboratory contamination was detected, clinical specimens were inoculated manually. It is likely that contamination occurred during inoculation or handling the culture plate after initial incubation. Automated specimen processing could minimize the risk of contamination. To enable early detection of pseudo-outbreaks, whole genome sequencing of newly identified MRSA isolates could be performed routinely in search for clusters within the laboratory specific database. We recommend to further investigate clusters without an epidemiological link and to consider screening laboratory employees when laboratory contamination is suspected. Further investigation into MSSA and MRSA carrying laboratory staff members using wgMLST could provide more evidence on the possible relationship between MSSA and MRSA carriage and microbiological laboratory work.

Conclusion

A pseudo-outbreak of MRSA was identified involving nine patients caused by MRSA carriage of a laboratory staff member who contaminated clinical specimens. Clonal relatedness between the samples suspected of contamination could be confirmed by wgMLST, showing the added value over MLVA-typing. This pseudo-outbreak emphasizes the importance of critical and continuous evaluation of microbiology laboratory procedures to minimize the possibility of laboratory contamination and to maximize early detection of false-positive culture results.

Availability of data and materials

Genomic sequences are available under the NCBI BioProject accession number PRJEB58118.

References

Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4.

Becker K, Heilmann C, Peters G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:870–926. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00109-13.

EUCAST subcommittee for detection of resistance mechanisms. EUCAST guidelines for detection of resistance mechanisms and specific resistances of clinical and / or epidemiological importance. 2017.

Weterings V, Veenemans J, van Rijen M, Kluytmans J. Prevalence of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in patients at hospital admission in The Netherlands, 2010–2017: an observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:1428.e1-1428.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.012.

Donker T, Bosch T, Ypma RJF, Haenen APJ, van Ballegooijen WM, Heck MEOC, et al. Monitoring the spread of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in The Netherlands from a reference laboratory perspective. J Hosp Infect. 2016;93:366–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2016.02.022.

Malachowa N, Sabat A, Gniadkowski M, Krzyszton-Russjan J, Empel J, Miedzobrodzki J, Kosowska-Shick K, Appelbaum PC, Hryniewicz W. Comparison of multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, spa typing, and multilocus sequence typing for clonal characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3095–100. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.7.3095-3100.2005.

Poynten M, Andresen DN, Gottlieb T. Laboratory cross-contamination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An investigation and analysis of causes and consequences. Intern Med J. 2002;32:512–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1445-5994.2002.00271.x.

Aronoff DM, Thelen T, Walk ST, Petersen K, Jackson J, Grossman S, et al. Pseudo-Outbreak of Clostridium sordellii Infection following Probable Cross-Contamination in a Hospital Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:640–2. https://doi.org/10.1086/652774.

Reigadas E, Vázquez-Cuesta S, Onori R, Villar-Gómara L, Alcalá L, Marín M, et al. Clostridioides difficile contamination in a clinical microbiology laboratory? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:340–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.027.

Dundar D, Meric M, Vahaboglu H, Willke A. Pseudo-outbreak of Serratia marcescens in a tertiary care hospital. New Microbiol. 2009;32:273–6.

Dutch Working party on infection prevention. Methicilline-resistente Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). 2017.

Dutch Foundation of the Working Party on Antibiotic Policy (SWAB), Dutch Centre for Infectious disease control. NethMap 2020. 2020.

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. EUCAST: Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. 2019.

Martineau F, Picard FJ, Roy PH, Ouellette M, Bergeron MG. Species-specific and ubiquitous-DNA-based assays for rapid identification of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:618–23. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.36.3.618-623.1998.

Hu Y, Xie Y, Tang J, Shi X. Comparative expression analysis of two thermostable nuclease genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9:265–71. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2011.1033.

Francois P, Renzi G, Pittet D, Bento M, Lew D, Harbarth S, et al. A novel multiplex real-time PCR assay for rapid typing of major staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3309–12. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.42.7.3309-3312.2004.

Killgore GE, Holloway B, Tenover FC. A 5’ nuclease PCR (TaqMan) high-throughput assay for detection of the mecA gene in staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2516–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.38.7.2516-2519.2000.

Nijhuis RHT, Van Maarseveen NM, Van Hannen EJ, Van Zwet AA, Mascini EM. A rapid and high-throughput screening approach for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus based on the combination of two different real-time PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2861–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00808-14.

Schouls LM, Spalburg EC, van Luit M, Huijsdens XW, Pluister GN, van Santen-Verheuvel MG, et al. Multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis of Staphylococcus aureus: comparison with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and spa-typing. PLoS ONE. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005082.

Schürch AC, Arredondo-Alonso S, Willems RJL, Goering RV. Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene–based approaches. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:350–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.016.

Sabat AJ, Hermelijn SM, Akkerboom V, Juliana A, Degener JE, Grundmann H, et al. Complete-genome sequencing elucidates outbreak dynamics of CA-MRSA USA300 (ST8-spa t008) in an academic hospital of Paramaribo. Republic of Suriname Scientific Reports. 2017;7:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41050.

Harris SR, Feil EJ, Holden MTG, Quail MA, Nickerson EK, Chantratita N, et al. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science. 2010;327:469–74. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1182395.

Wurtz N, Papa A, Hukic M, Di CA, Leparc-Goffart I, Leroy E, et al. Survey of laboratory-acquired infections around the world in biosafety level 3 and 4 laboratories. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:1247–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-016-2657-1.

Jager MM, Murk JLAN, Pique R, Wulf MWH, Leenders ACAP, Buiting AG, et al. Prevalence of carriage of meticillin-susceptible and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in employees of five microbiology laboratories in The Netherlands. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:292–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2009.11.003.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of the laboratory staff members of the bacteriology department of the Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of the Microvida sequencing team for performing the whole genome sequencing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.V. set up the study. K.G., A.O. and A.B. performed investigation and management of the outbreak. K.H., J.S. and J.V. analyzed the data. V.W. and K.C. critically reviewed the analysis. K.H. wrote the main manuscript with the contributions from all coauthors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data of patients used in this study were part of routine clinical practices in Elisabeth-TweeSteden hospital and their anonymous use is beyond the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary table 1.

Quality control values of whole genome sequencing.

Additional file 2. Supplementary table 2.

Distance matrix of the wgMLST analysis of the MRSA strains from the laboratory database with MLVA type complex MC0022, MLVA type MT0489 and MLVA profile 18-05-03-01-01-13-01-05 and the two medical microbiology technicians tested positive for MRSA in the pseudo-outbreak investigation. The colors of the isolate IDs and the colored absolute number of allelic differences correspond to the cluster they belong to as depicted in Figure 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Houkes, K.M.G., Stohr, J.J.J.M., Gast, K.B. et al. A pseudo-outbreak of MRSA due to laboratory contamination related to MRSA carriage of a laboratory staff member. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 12, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-022-01207-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-022-01207-7