Abstract

Background

Knowledge of infection prevention and control (IPC) procedures among healthcare workers (HCWs) is crucial for effective IPC. Compliance with IPC measures has critical implications for HCWs safety, patient protection and the care environment.

Aims

To discuss the body of available literature regarding HCWs' knowledge of IPC and highlight potential factors that may influence compliance to IPC precautions.

Design

A systematic review. A protocol was developed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis [PRISMA] statement.

Data sources

Electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Proquest, Wiley online library, Medline, and Nature) were searched from 1 January 2006 to 31 January 2021 in the English language using the following keywords alone or in combination: knowledge, awareness, healthcare workers, infection, compliance, comply, control, prevention, factors. 3417 papers were identified and 30 papers were included in the review.

Results

Overall, the level of HCW knowledge of IPC appears to be adequate, good, and/or high concerning standard precautions, hand hygiene, and care pertaining to urinary catheters. Acceptable levels of knowledge were also detected in regards to IPC measures for specific diseases including TB, MRSA, MERS-CoV, COVID-19 and Ebola. However, gaps were identified in several HCWs' knowledge concerning occupational vaccinations, the modes of transmission of infectious diseases, and the risk of infection from needle stick and sharps injuries. Several factors for noncompliance surrounding IPC guidelines are discussed, as are recommendations for improving adherence to those guidelines.

Conclusion

Embracing a multifaceted approach towards improving IPC-intervention strategies is highly suggested. The goal being to improve compliance among HCWs with IPC measures is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are a major problem for patients' and healthcare workers' (HCWs') safety and their prevention must be a top priority for healthcare systems and organizations [1,2,3,4]. HAIs prevalence ranges from 5 to 15% of hospitalized patients and can affect 9–37% of those admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) [5]. At any one time in the United States (US), 1 out of every 25 hospitalized patients are affected by a HAI [6].

HAIs can result in low quality of life, or even reduce life expectancy of the infected person, as well as incur considerable costs in the long run [4, 7,8,9]. For example, the risk of HAIs following a needle-stick injury with needle from an infected source patient was 0.3% for HIV, 3% for hepatitis C and 6–30% for hepatitis B [10]. A total of 3 million out of 35 million HCWs worldwide experienced percutaneous exposure to bloodborne pathogens (BBPs) each year; 2 million of those were to HBV; 0.9 million to HCV; and 0.17 million to HIV [11]. The annual economic impact of HAIs in the US alone was approximately US$ 6.5 billion [9]. HAIs have also been reported to contribute to serious mental health disorders, including anxiety, depression, adjustment disorder, panic attacks, and post-traumatic stress disorder [12, 13]. Figure 1 illustrates patient's worriment about HCW's noncompliance with the IPC. The size and scope of the HAIs burden worldwide appears to be very important and quite underestimated. Methods to assess the size and nature of the problem exist, however, these tools need to be simplified and adapted so as to be affordable in settings where resources and data sources are limited. Similarly, preventive measures are often simple to implement, such as hand hygiene. IPC must reach a higher position among the first priorities in national health programmes, especially in resource constrained countries [5].

Luckily, as many as 55–70% of HAIs may be preventable [4]. To prevent HAIs, measures such as standard precautions (including hand hygiene, use of gloves, gowns, eye protection, use of cough etiquette, and safe disposal of sharp instruments) and isolation precautions used to interrupt the risk of transmission of pathogens (contact, droplet, and airborne precautions) are recommended and implemented widely [14]. Prevention of specific infections, prophylaxis after exposure to BBPs and immunizations for HCWs are another IPC measures followed to reduce the rate of HAIs [14].

Knowledge of HCWs is fundamental for effective IPC [5, 11, 15]. Lack of knowledge of guidelines for IPC—combined with an unawareness of preventive indications during daily patient care and the potential risks of transmission of microorganisms to patients—constitute barriers to IPC compliance [16,17,18]. Lack of knowledge about the appropriateness, efficacy and use of IPC measures determine poor compliance [19,20,21,22]. To overcome these barriers, education and training are the cornerstones of improvement in IPC practices [23, 24]. HCWs should be aware of the fact that knowledge is power. However, lack of knowledge of IPC measures has been repeatedly shown after education and training [24, 25]. HCWs' awareness should include issues related to hand hygiene, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), immunization for prevention of communicable diseases, modes of infection transmission, assessment of patients for infection, medical instrument decontamination, healthcare waste handling, and needle stick and sharp safety policy. Even more importantly, HCWs should be compliant to these IPC precautions, methods and strategies to ensure HAIs reduction in the healthcare settings [20].

Compliance with IPC practices, including hand hygiene and use of PPE, has been found to vary widely among HCWs [20, 26, 27] and is likely influenced by one’s knowledge about infection risk and behaviours [16, 18, 27,28,29,30,31,32]. However, good knowledge does not necessarily predict good IPC practice [8, 33, 34]. For example, HCWs have been found to demonstrate poor compliance with hand hygiene practices despite well-established guidelines for the prevention of HAIs [35, 36].

More confounding variables of good IPC practice other than knowledge or experience exist.

Given the potential negative impacts on patients and HCWs by HAIs, clinical and national economic and psychological burden as mentioned, it is important to discuss literature on HCWs' knowledge of IPC to prevent such harmful exposures. Moreover, this paper will also focus on reviewing potential factors influencing compliance of HCWs with the IPC measures so that some suggestions can be made to improve the quality and safety of health service delivery and the health outcomes of the people who access those services.

Methods

Design

This systematic review was conducted with reference to the basics of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [37], described as stated by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis [PRISMA] statement [38]. A systematic review protocol was developed based on PRISMA-P and the PRISMA statement. Published articles in English from 1 January 2006, to 31 January 2021, were retrieved for review from 7 electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Proquest, Wiley online library, Medline, and Nature). Search terms included knowledge, awareness, healthcare workers, infection, control, comply, compliance, prevention and factors. Relevant papers were identified by three independent readers using predefined exclusion criteria, firstly on the basis of abstracts, secondly by assessing full-text papers. The title and abstract of each retrieved article were read, and the article was retained if it discussed HCW's knowledge of IPC or highlighted likely factors influencing compliance to the IPC precautions.

Inclusion–exclusion criteria

Articles were eligible for inclusion in this review when they met all of these criteria: (1) reported on HCWs' knowledge and/or compliance of IPC; (2) used a quantitative, qualitative or combined method; and (3) published between January 2006 and January 2021 in English. Articles were excluded if they met one of the following criteria: (1) editorials, commentaries, news analyses, reviews and systematic reviews or meta-analyses; (2) small sample size (studies with respondents of ≤ 100); or (3) undertaken repeated methods (similar outcome measures, design, survey questionnaire tools and/or respondents of the study). Studies involving the following group of HCWs were included in the review: physicians, nurses, nurse assistants, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, midwives, laboratory specialists and technicians, laboratory technologists, radiographers, community health workers, health officers, hospital orderlies, and other healthcare professionals.

Topics of interest for the outcomes’ measures were: standard or universal precautions (hand hygiene; wearing PPE, glove use, mask use, and protective eyewear use; sharps safety; safe injection practices; and sterile instruments and devices). Comparable outcomes on respiratory hygiene IPC measures designed to limit the transmission of respiratory pathogens spread by droplet or airborne routes [tuberculosis (TB), methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Ebola] were included. Findings on HCWs knowledge of IPC measures necessary to stop HAIs like occupational vaccinations (HBV, varicella, influenza and COVID-19); and infections transmitted through needle stick and sharp injuries (NSSIs), awareness of national injection safety policy, and healthcare waste handling, care to prevent urinary catheters- and central venous catheters (CVCs)-related infections were also considered. Both observed and self-report measures of these outcomes were examined.

Data extraction

Three researchers (S.A., A.A. and A.R.) independently screened titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies for eligibility. The full text was then reviewed to confirm an eligibility criteria match. Disagreements between the three reviewers after full text screening were reconciled via consensus by fourth, fifth and sixth reviewers (Z.A., G.A. and J.A.). Data were extracted from the relevant research studies using key headings which are noted in Tables 1 and 2, simplifying analysis and review of the literature. Articles were categorized as a survey report, an observational study, or a semi-structured interview study. The following data were extracted from retrieved studies: authors, publication year, study location and aim, setting, sample size, methodology and assessment of study risk of bias, and outcome. Appropriate quality appraisal guides and checklists were used to evaluate the quality of the survey and observational studies and the semi-structured interviews studies [39, 40] involved in this review. Three investigators (S.A., A.A., and Z.A.) separately evaluated the possibility of bias using these tools. Quality assessment items were based on research problems, research design, study sample, data collection, results, and limitations.

Data analysis

Preliminary screening of eligible studies revealed large considerable heterogeneity in terms of participants, setting, sample size, response rates and outcome measures. Primary analysis of studies was, therefore, limited to qualitative synthesis, allowing a detailed analysis of the data to be performed.

Results

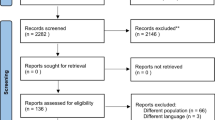

A total of 3417 publications were retrieved; of which 30 were eligible for final analysis. The PRISMA chart for the studies included is displayed in Fig. 2. Research methodologies were predominantly self-report questionnaires (n = 26), some of which were cross-sectional surveys using a questionnaire (n = 14) and observation techniques (n = 2). Other methodologies were semi-structured interview studies (n = 5) targeted at individual and institutional levels. The sampling method in most studies was convenience sampling (n = 22). Thirty studies conducted on 16,081 HCWs entered the final stage. The majority of the studies were conducted in high-income countries [n = 16; (United States = 4, England = 3, Italy = 2, France = 2, Saudi Arabia = 1, Poland = 1, China = 1, and European countries = 1)]; while others originated from lower-middle-income countries [n = 6; (Nigeria = 3, Vietnam = 1, India = 1, and Nepal = 1)], and low-income countries [n = 8; (Ethiopia = 6, Guinea = 1, and Democratic Republic of Congo = 1)]. Samples ranged from 102 HCWs to multiple sites. Most of the sampled studies were from hospital settings (28 studies), at least 9 of which focused on acute hospital settings. The majority of studies were undertaken in intensive or critical care units, outpatient departments, emergency departments, primary health care centres, maternity units or paediatric or neonatal hospitals, with others taking place in long-term care facilities, medicine and surgery, cardiac, renal, dental, urology, and psychiatry.

All studies had a high level of quality (low bias), and except for 3 studies [30, 41, 42], all others used nonstandardized questionnaire survey instruments. Most of the studies included nurses (29 studies) or doctors (23 studies). Other types of HCWs included in the studies were allied healthcare workers such as pharmacists and pharmacy technicians, dentists, midwives, laboratory specialists and technicians, laboratory technologists, radiographers, community health workers, and health officers; ancillary staff with responsibility for patient care, such as porters and domestic workers. The sampled studies focused on HCWs’ knowledge and compliance of standard or universal precautions [13], awareness of IPC national and international guidelines or recommendations [5], NSSIs precautions [2], and urinary catheters- and CVCs-related infections [2], healthcare waste handling [1]; and views and experiences with regards to IPC for TB (3 studies), influenza [3], COVID-19 [2], HBV [2], H1N1 [1], MERS [1] MRSA [1], Ebola [1] or varicella [1]. Summary of the characteristics of the included studies that have assessed the knowledge of IPC among HCWs (n = 26) and highlighted potential factors influencing compliance to the IPC precautions (n = 22) is available in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Additional findings of descriptive and professional guidelines are noted throughout the text.

Knowledge of IPC among HCWs

Twenty-six out of 30 of the included studies examined knowledge level. In most studies, the HCWs IPC knowledge was measured by question items in which responses were answered in a point Likert scale or yes and no options. The level of knowledge in different studies had been mainly categorized as aware, adequate, high, knowledgeable, good and fair. We mentioned the most common level of knowledge in each study. Out of the 26 studies, level of knowledge was characterised as: “aware” (range: 77.9–94.7%, n = 5 studies), “adequate” (range: 70.8–84.7%, n = 2 studies), “high” (range: 80.2–84%, n = 3 studies), and “knowledgeable” (range: 53.7–76%, n = 2 studies); respectively. Four studies also reported level of knowledge as excellent (≥ 90%, n = 1), good (74.4–99%, n = 2), and fair (60%, n = 1). In the group of 3 studies, the most common level of knowledge was characterized as low (range: 25–34%) or poor (50%) (Table 1).

Findings regarding knowledge of IPC measures were mixed. On the one hand, the level of HCWs knowledge on IPC was adequate, good, excellent and/or high in relation to standard precautions (use of gloves, mask, gowns and protective eye wear), hand hygiene, IPC measures for TB, MRSA, MERS-CoV, COVID-19 and Ebola, and care pertaining to urinary catheters [8, 27, 29, 34, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. On the other hand, although awareness of children's hospital HCWs toward mandatory influenza vaccination was high, knowledge of HCWs about the occupational vaccinations, namely, HBV, varicella and influenza was low [51,52,53].

Analyses of the reviewed studies indicated specific variation in the knowledge of IPC from one country to another. For instance, in comparison with the high mean knowledge of HCWs in Italy and Nepal on main methods of transmission for microorganisms, only half of the HCWs in an Indian study understood disease transmission through NSSIs and less than one-third of Italian HCWs knew that they could transmit these infections to a patient [3, 29, 44]. Low level of knowledge on modes of transmission among HCWs was also evident in another Italian and a Nigerian study [8, 16]. In a 22-European country survey, the mean score of the nurses' knowledge on the CDC guidelines for preventing CVCs-related infections was low [41]. A British study demonstrated that HCWs never had the correct understanding about the level of isolation required for MRSA patients [27]; and an American study shown nurses and their aides were less aware of research-proven recommendations for urinary catheter patients [50]. Two Ethiopian studies found low percentage of HCWs were knowledgeable towards IPC [19]; and only few HCWs knew that respirators can provide protection from inhaling TB pathogen and the use of ventilator can minizine risk of TB infection [48]. Furthermore, two Nigerian studies shown HCWs had poor awareness of the risks of infection following exposure to BBDs and injection safety; and HCWs were unable to recognize vaccination, post exposure prophylaxis, surveillance for emerging diseases, and the national injection safety policy and policy on sharps disposal [8, 34].

Sources of information for HCWs on knowledge of IPC included public media [16, 42, 46]; healthcare providers (IPC practitioners, hospital epidemiologists and nurses) [16, 46, 47]; internet and intranet [16, 42, 46, 47]; medical journals [3, 43, 46]; Ministry of Health’s websites, memos and helplines [42, 43]; hospital’s newspapers [46, 47]; IPC committee [47]; posters [47]; educational courses [3]; and hospital training [46]. HCWs reported learning from didactic formal [in-services, lectures, and nursing school and nurse aides' courses] and informal [prior experience, nurse supervisors, co-workers, and facility policies] methods; and some HCWs gained their knowledge both informally and formally [27].

Several associations were found between HCWs' knowledge and other variables (such as experience, training, working abroad, availability of IPC guidelines, participation in an IPC committee, and receiving information through scientific journals) [3, 16,17,18, 34, 41, 48, 54]. HCWs who taking IPC training and education [17, 18, 34, 48, 54], having long work experience [17, 18, 41, 54], had IPC guidelines [17, 18], received information through medical journals [3, 16] and participated in an IPC committee [18] were more likely to be knowledgeable on IPC. HCWs with an educational level of bachelor, master or above had more knowledge on IPC than HCWs holding diplomas [54]. Being a doctor or a nurse, rather than a nurse assistant, midwife, laboratory technologist or scientist, pharmacist, community health worker, house officer, and other type of HCWs was consistently associated with more knowledge of injection safety, infection preventive measures, CDC hand hygiene guidelines, and influenza vaccine recommendations [3, 8, 30, 31, 34, 42, 47, 51].

Factors influencing compliance of HCWs with IPC

Most studies assessed compliance with IPC by means of self-reporting, using self-developed questionnaires and few studies measured compliance using direct observation by a trained observer (Table 2). Several factors that may affect HCWs' compliance and noncompliance with the IPC measures were reported in many research studies [3, 8, 17, 19, 21, 26, 30, 34, 47, 49, 53, 55, 56]. Three of the major factors prompting HCWs to comply with the IPC measures were knowledge, education and training, and experience [8, 17,18,19, 26, 30, 34, 47, 49]. For instance, more awareness of the IPC benefits and procedures and the perception of risk associated with not following IPC recommendations motivated HCWs to be more compliant [3, 8, 47]. HCWs who reported receiving enough training and education on IPC were much more compliant [17,18,19, 26, 34, 49]. Also, HCWs who cared longer for patients with a history of infective diseases or participated in IPC committees were more adherent to IPC practices [26, 34, 42, 47]. Being a doctor rather than a nurse was associated with lower compliance with hand hygiene guidelines, PPE use and IPC practices [21, 26]. Compliance was the lowest in ICUs compared with non-ICU wards or surgical wards [17, 26], and higher when HCWs were working at public, secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities [26, 53] and during performing procedures that carried more exposure to blood products and body fluid or when HCWs were fearful of acquiring BBDs [26, 53]. Compliance of HCWs with IPC in the urban hospitals was better than in the rural ones [31, 53]. Other factors identified for good adherence to IPC practices were older age, positive attitude and non-Hispanic black race [21].

Predictors of HCWs noncompliance included high workload [31, 34] and time constraints [34], more beds and/or higher patient-to-nurse ratio [3, 19], and professional category-specific [47]. Glove overuse seemed to reduce hand hygiene compliance [56]. Noncompliance of HCWs to occupational vaccinations recommendations was due to lack of fear of contracting the infection (e.g. influenza A/H1N1) [16], doubts about vaccine efficacy [51], belief that vaccine is useless or dangerous [16], and fear of vaccine side effects [51]. Reported barriers for HCWs to adhere with standard precautions included nonavailability of equipment (alcohol hand rub, nearby sink, soap or paper towels) [17, 26, 30, 31, 49, 53] and intolerable or difficult to use hand hygiene agents [47, 49]. Lack of implemented IPC protocols [16, 17, 49]; HCWs belief that patients pose no health risk on them or patients cannot be a source of infection as if they were asymptomatic or unaware that they are infected; or following IPC recommendations interferes with providing good patient care resulted in less IPC adherence [26].

Discussion

There appears to be gaps in some HCWs' knowledge of occupational vaccinations (HBV, varicella and influenza), modes of transmission of infectious diseases (HBV, HCV, HIV, and influenza A/H1N1), the risk of infection from NSSIs, the understanding that needle and sharp safe practices are enough to protect against BBPs, and the CDC guidelines for preventing CVCs-related infections. Lack of knowledge of IPC among HCWs has been linked to the worsening of the healthcare delivery outcomes [1, 7, 57]. For instance, insufficient knowledge of HCWs about occupational vaccinations resulted in low coverage of HCWs for hepatitis B [28, 43], influenza A/H1N1 [16, 43, 51], meningococcal [43], and COVID-19 [42] vaccines. Majority of HCWs does not vaccinate against the common pathogens [54]. These unsafe practices may increase exposures and infections among HCWs and impede control of infectious disease outbreaks [58]. Therefore, as vaccine coverage is associated with knowledge [51], education and training should be strengthened to increase the adhesion of HCWs to vaccinations. Many studies shown HCWs received insufficient training and education on IPC and they needed more education and training [34, 42,43,44,45, 48,49,50, 53]; and in some studies, HCWs admitted that, away from their professional education, they did not receive any training or orientation on IPC in the prior year or were not sure whether they had received training [17, 30, 59, 60]. Some HCWs stated that training was only available for administrators, not frontline HCWs [61]. Education and training is recommended as a core component for effective IPC programmes by the World Health Organization [WHO] [62]. Effective education and training of HCWs on IPC is beneficial and has reduced HAIs and combated antimicrobial resistance (AMR) considerably [23, 24, 63, 64]. Educational programmes have been reported as an essential ingredient for success in IPC strategies, including increasing HCWs acceptance of occupational vaccinations [51], the control of ventilator-associated pneumonia [65, 66], reducing needlestick injuries [67], and the implementation of isolation precautions [68]. There are also reports on the effective use of education for hand hygiene promotion strategies outside the acute hospital care setting [69]. It is important, therefore, to continue to use the formal education programme as one feature of the implementation strategy for IPC improvement in health care. There was a positive correlation between good knowledge and compliance among the HCWs [8, 18, 70,71,72,73]. Training and education are necessary if full compliance to IPC guidelines is to be achieved [18, 30, 74]. Therefore, health care facilities need to arrange training sessions for all HCWs to improve their knowledge and to improve their level of compliance.

Knowledge of IPC among HCWs other than physicians and nurses was lower in comparison with physicians and nurses, and their role in tackling HAIs is pivotal. Basically, this could be due to lower level of academic education and training about IPC in HCWs other than physicians or nurses. The role of HCWs other than physicians and nurses in hospital IPC is usually underestimated [75, 76] although they themselves and their work can be a vector of infection transmission in hospitals. HCWs other than physicians and nurses may be in close contact between patients; physicians, and/or nurses; high concentrations of medically-vulnerable populations, combined with physical movement between treatment areas; which may facilitate HAI spread within health care institutions and the community. Therefore, WHO guidelines recommend that IPC education and training should be in place for all HCWs using team- and task-based strategies, including bedside and simulation training [62]. Inclusion of educational curricula and continuing refresher education programs about IPC can be recommended for HCWs other than physicians and nurses to ensure a thorough knowledge and understanding of IPC. Although educational initiatives have so far not been consistently associated with good IPC practices [61, 77,78,79], targeted materials and training can help ensure understanding among HCWs and healthcare facility visitors [80]. Since different categories of HCWs may have different information needs, it is recommended that IPC training sessions be tailored to the specific target audience, e.g., medical staff versus cleaning services staff. Education is important to address HCWs’ concerns, fears, stigmas and incorrect assumptions regarding transmission or prevention of HAIs.

While HAIs burden is already demanding in developed countries, magnitude of the problem is intensified in healthcare organizations where basic IPC measures are not available mainly due to limited financial resources. Familiarity with IPC measures is challenging even in highly resourced countries and may appear an unrealistic goal in everyday care in resource constrained countries with financial constraints [5]. Limited resources are a common contributor to poor IPC practices [30, 61, 81]. Therefore, simple and affordable preventive measures such as hand hygiene should be adapted in the healthcare settings of resource constrained countries. Hand hygiene is the initial step towards successful IPC and still remains the basic and most effective measure to prevent pathogen transmission and infection. Simple hand hygiene when performed well can reduce the prevalence of HAIs substantially [5].

HCWs has been known to get infected during disease outbreaks and pandemics such as MERS-CoV outbreak [82] as well as the COVID-19 pandemic [83] due to poor compliance with the basic IPC measures. IPC recommendations in response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and other corona viruses should be informed by these previous well-established IPC knowledge and experiences, and perhaps infection preventive guidelines influenced by them to a certain extent; and should include standard precautions and droplet or airborne precautions [62].

Organized national programs or campaigns shown to highly promote IPC and ensure effective implementation of strategies and guidelines and have a favourable effect on HCWs' IPC knowledge and improved compliance [64, 79, 84]. National interventions for IPC undertaken in the context of a high-profile political drive can reduce selected HAIs [84].

Unfortunately, good knowledge does not necessarily predict good practice [8, 33, 34, 53].

More confounding variables of good IPC practice other than knowledge or experience exist. Nonavailability of resources, high workload and time limitation have been reported as the main factors influencing HCWs' compliance with IPC practice [26, 30, 34, 49, 53]. Factors that impact on compliance is organized into three overarching domains: organisational, environmental and individual factors [85]; which allows HCWs, managers and policy makers to see clearly where strategies need to be implemented to facilitate compliance and support HCWs. Reported compliance with IPC in the public, secondary and tertiary hospitals was likely to be better than in the private or primary ones. This might be possibly related to poorer conditions for IPC at the private or primary hospitals. Poor compliance with IPC practices has been observed both in high- and low-income settings and across health settings [22, 55]. Identifying roles and responsibilities of a team and making IPC initiatives its top priority in addition to influence by peer pressure group could play a role in determining HCW's different motivations for compliance [55].

HCWs seem to be selective in adhering to IPC measures rather than practicing comprehensive safe standard precautions when engaging in contact with patients which may result in an unnecessary risk. In particular, during performing procedures that carry more exposure to blood products and body fluid or when dealing with sharps, compliance is good. While many researchers have investigated in the area of compliance with IPC guidelines and reasons for non-adherence [22, 86], with a lack of knowledge regularly being identified by staff as affecting their compliance, the opinions of HCWs about what would improve their own practice may need to be questioned further.

IPC behaviour varies significantly among HCWs, thus suggesting that individual features could play a role in determining behaviour [20, 26, 27]. There is a danger in ignoring all-important ‘individual differences’ and a call to limit this approach within health psychology has previously been made [87]. To improve HCWs’ compliance with practices, IPC should learn from the behavioural sciences [88]. Social psychology attempts to understand these features, and individual factors such as social cognitive determinants may provide additional insight into IPC behaviour [89]. Application of social cognitive models and psychological principles in intervention strategies has resulted in a change towards positive behaviour in IPC [90,91,92]. Current models that help to explain human behaviour can be classified on the basis of being directed at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, or community levels [32, 89]. Intrapersonal factors are individual characteristics that influence behaviour such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and personality traits. Interpersonal factors include interpersonal processes and primary groups, i.e., family, friends and peers, who provide social identity, support and role definition. Community factors are social networks and norms that exist either formally or informally between individuals, groups and organizations [32, 89].

Multifaceted approach (e.g. education, training, observation, feedback, easy access to hand hygiene supplies, dedication of financial resources, praises by superior, strong hospital leadership, prioritization to IPC needs, collaborating with a private advertising firm in a marketing campaign and active participation at institutional level) is highly suggested to reduce HAIs by improving compliance among HCWs with IPC measures [93, 94].

Limitations

Subject variability and study outcomes meant to be measured to affect the validity of this review and invalidate the findings. Lack of homogeneity among the studies included. We were not able to perform any type of meta-analysis because of the large methodological differences. There are methodologic issues with almost all the included studies in relation to credibility, transferability, and confirmability. The research methodologies were predominantly cross-sectional surveys using a questionnaire; some of which were self-report questionnaires and observation techniques. Clearly, this does raise some methodological issues in terms of the reliability of observational data and self-report questionnaires, and the probability of observer and social desirability affecting the results. The majority of the participants included in these research studies were nurses or doctors. The exclusion of studies published in languages other than English may have impacted on the richness of the data included in this review. Furthermore, some of the studies failed to report on the type of instrument used for obtaining the data or on how observers were trained. This makes comparison and interpretation of the results difficult, not only in this review but in general for researchers interested in knowledge of IPC amongst HCWs and factors influencing compliance studies.

Conclusion

This review intended to discuss literature on knowledge of IPC among HCWs and factors influencing compliance. Overall, the level of HCWs knowledge on IPC seems to be adequate towards standard precautions, hand hygiene, and IPC measures for TB, MRSA, MERS-CoV, and COVID-19, and care pertaining to urinary catheters. There appears to be gaps in some HCWs' knowledge of occupational vaccinations (HBV, varicella and influenza), modes of transmission of infectious diseases (HBV, HCV, HIV, and influenza A/H1N1), the risk of infection from NSSIs, the understanding that needle and sharp safe practices are enough to protect against BBPs, and the CDC guidelines for preventing CVCs-related infections. Several factors may affect HCWs' compliance and noncompliance with the IPC measures: knowledge, education and training, experience, lack of supplies (alcohol hand rub, nearby sink, soap or paper towels), working in ICU or surgical ward, working at public or secondary or tertiary hospital, and working for a patient with exposure to blood or body fluid. Barriers to comply with IPC may include workload, insufficient time, professional category and low patient-to-nurse ratio. It is highly suggested that adopting a multifaceted approach to IPC improvement intervention strategies has been shown to reduce HAIs and improve compliance among HCWs with IPC measures.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request, please contact author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- IPC:

-

Infection prevention and control

- HCWs:

-

Healthcare workers

- HAIs:

-

Healthcare-associated infections

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-Analyses

- PPE:

-

Personal protective equipment

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- CDC:

-

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

- ICUs:

-

Intensive care units

- BBPs:

-

Bloodborne pathogens

- NSSIs:

-

Needle stick and sharps injuries

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- CVCs:

-

Central venous catheters

- BBDs:

-

Blood borne diseases

References

Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Healthcare‐associated infection in developing countries: simple solutions to meet complex challenges. JSTOR; 2007.

Al-Omari A, Al Mutair A, Alhumaid S, Salih S, Alanazi A, Albarsan H, et al. The impact of antimicrobial stewardship program implementation at four tertiary private hospitals: results of a five-years pre-post analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–9.

Parmeggiani C, Abbate R, Marinelli P, Angelillo IF. Healthcare workers and health care-associated infections: knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in emergency departments in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):1–9.

Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Doshi JA, Agarwal R, Williams K, Brennan PJ. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(2):101–14.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. First global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care 2009 [10 February 2021]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44102/9789241597906_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care–associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198–208.

Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9761):228–41.

Iliyasu G, Dayyab FM, Habib ZG, Tiamiyu AB, Abubakar S, Mijinyawa MS, et al. Knowledge and practices of infection control among healthcare workers in a Tertiary Referral Center in North-Western Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2016;15(1):34.

Stone PW, Braccia D, Larson E. Systematic review of economic analyses of health care-associated infections. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33(9):501–9.

United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Exposure to Blood: What Healthcare Personnel Need to Know 2003 [16 April 2021]. https://www.who.int/occupational_health/activities/2brochure.pdf.

World Health Organization. Needlestick injuries. Protecting health-care workers—preventing needlestick injuries 2012 [10 February 2021]. https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/needinjuries/en/.

Wicker S, Stirn A, Rabenau H, Von Gierke L, Wutzler S, Stephan C. Needlestick injuries: causes, preventability and psychological impact. Infection. 2014;42(3):549–52.

Zhang M-X, Yu Y. A study of the psychological impact of sharps injuries on health care workers in China. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):186–7.

United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings 2007 [cited 10 February 2021]. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/isolation-guidelines-H.pdf.

World Health Organization. Improving infection prevention and control at the health facility. Interim practical manual supporting implementation of the WHO Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes 2018 [10 February 2021]. https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/tools/core-components/facility-manual.pdf.

Albano L, Matuozzo A, Marinelli P, Di Giuseppe G. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of hospital health-care workers regarding influenza A/H1N1: a cross sectional survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):1–7.

Assefa J, Diress G, Adane S. Infection prevention knowledge, practice, and its associated factors among healthcare providers in primary healthcare unit of Wogdie District, Northeast Ethiopia, 2019: a cross-sectional study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;9(1):1–9.

Geberemariyam BS, Donka GM, Wordofa B. Assessment of knowledge and practices of healthcare workers towards infection prevention and associated factors in healthcare facilities of West Arsi District, Southeast Ethiopia: a facility-based cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):1–11.

Aloush SM, Al-Sayaghi K, Tubaishat A, Dolansky M, Abdelkader FA, Suliman M, et al. Compliance of Middle Eastern hospitals with the central line associated bloodstream infection prevention guidelines. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;43:56–60.

Haile TG, Engeda EH, Abdo AA. Compliance with standard precautions and associated factors among healthcare workers in Gondar University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. 2017.

Russell D, Dowding DW, McDonald MV, Adams V, Rosati RJ, Larson EL, et al. Factors for compliance with infection control practices in home healthcare: findings from a survey of nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward infection control. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(11):1211–7.

Smiddy MP, O’Connell R, Creedon SA. Systematic qualitative literature review of health care workers’ compliance with hand hygiene guidelines. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(3):269–74.

Safdar N, Abad C. Educational interventions for prevention of healthcare-associated infection: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):933–40.

Ward DJ. The role of education in the prevention and control of infection: a review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(1):9–17.

Atack L, Luke R. Impact of an online course on infection control and prevention competencies. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(2):175–80.

Ganczak M, Szych Z. Surgical nurses and compliance with personal protective equipment. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(4):346–51.

Mody L, Saint S, Galecki A, Chen S, Krein SL. Knowledge of evidence-based urinary catheter care practice recommendations among healthcare workers in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1532–7.

Abeje G, Azage M. Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1–6.

Arora A, Gupta A, Sharma S. Knowledge, attitude and practices on needle-stick and sharps injuries in tertiary care cardiac hospital: a survey. Indian J Med Sci. 2010;64(9):396.

Ashraf MS, Hussain SW, Agarwal N, Ashraf S, El-Kass G, Hussain R, et al. Hand hygiene in long-term care facilities: a multicenter study of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and barriers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(7):758–62.

Chuc NTK, Hoa NQ, Lan PT, Thoa NTM, Riggi E, Tamhankar AJ, et al. Knowledge and self-reported practices of infection control among various occupational groups in a rural and an urban hospital in Vietnam. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–6.

Whitby M, Pessoa-Silva C, McLaws M-L, Allegranzi B, Sax H, Larson E, et al. Behavioural considerations for hand hygiene practices: the basic building blocks. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(1):1–8.

Madan AK, Raafat A, Hunt JP, Rentz D, Wahle MJ, Flint LM. Barrier precautions in trauma: is knowledge enough? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2002;52(3):540–3.

Ogoina D, Pondei K, Adetunji B, Chima G, Isichei C, Gidado S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of standard precautions of infection control by hospital workers in two tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. J Infect Preven. 2015;16(1):16–22.

McGuckin M, Waterman R, Govednik J. Hand hygiene compliance rates in the United States—a one-year multicenter collaboration using product/volume usage measurement and feedback. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(3):205–13.

Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Role of hand hygiene in healthcare-associated infection prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(4):305–15.

Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley; 2019.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;2015:349.

Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–9.

Williamson KM. Evidence-based practice: critical appraisal of qualitative evidence. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2009;15(3):202–7.

Labeau SO, Vandijck DM, Rello J, Adam S, Rosa A, Wenisch C, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for preventing central venous catheter-related infection: results of a knowledge test among 3405 European intensive care nurses. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):320–3.

Michel-Kabamba N, Ngatu NR, Leon-Kabamba N, Katumbo-Mukemo A, Mukuku O, Ngoyi-Mukonkole J, et al. Occupational COVID-19 prevention among congolese healthcare workers: knowledge, practices, PPE compliance, and safety imperatives. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6(1):6.

Alsahafi AJ, Cheng AC. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of healthcare workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to MERS coronavirus and other emerging infectious diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(12):1214.

Paudyal P, Simkhada P, Bruce J. Infection control knowledge, attitude, and practice among Nepalese health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(8):595–7.

Raab M, Pfadenhauer LM, Millimouno TJ, Hoelscher M, Froeschl G. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards viral haemorrhagic fevers amongst healthcare workers in urban and rural public healthcare facilities in the N’zérékoré prefecture, Guinea: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–8.

Shi Y, Wang J, Yang Y, Wang Z, Wang G, Hashimoto K, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of medical staff in Chinese psychiatric hospitals regarding COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020;4:100064.

Tavolacci M, Merle V, Pitrou I, Thillard D, Serra V, Czernichow P, et al. Alcohol-based hand rub: influence of healthcare workers’ knowledge and perception on declared use. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64(2):149–55.

Temesgen C, Demissie M. Knowledge and practice of tuberculosis infection control among health professionals in Northwest Ethiopia; 2011. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–7.

Tenna A, Stenehjem EA, Margoles L, Kacha E, Blumberg HM, Kempker RR. Infection control knowledge, attitudes, and practices among healthcare workers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol Off J Soc Hosp Epidemiol Am. 2013;34(12):1289.

Trigg D, Timmons S, Pynegar C. An audit of healthcare workers’ knowledge of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) against current infection control standards. Br J Infect Control. 2008;9(1):30–3.

Loulergue P, Moulin F, Vidal-Trecan G, Absi Z, Demontpion C, Menager C, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and vaccination coverage of healthcare workers regarding occupational vaccinations. Vaccine. 2009;27(31):4240–3.

Douville LE, Myers A, Jackson MA, Lantos JD. Health care worker knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding mandatory influenza vaccination. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(1):33–7.

Amoran O, Onwube O. Infection control and practice of standard precautions among healthcare workers in northern Nigeria. J Glob Infect Dis. 2013;5(4):156.

Desta M, Ayenew T, Sitotaw N, Tegegne N, Dires M, Getie M. Knowledge, practice and associated factors of infection prevention among healthcare workers in Debre Markos referral hospital. Northwest Ethiopia BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–10.

Shah N, Castro-Sánchez E, Charani E, Drumright L, Holmes A. Towards changing healthcare workers’ behaviour: a qualitative study exploring non-compliance through appraisals of infection prevention and control practices. J Hosp Infect. 2015;90(2):126–34.

Flores A, Pevalin DJ. Healthcare workers’ compliance with glove use and the effect of glove use on hand hygiene compliance. Br J Infect Control. 2006;7(6):15–9.

Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL, Sheridan SE, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 2010.

AlJohani A, Karuppiah K, Al Mutairi A, Al MA. Narrative review of infection control knowledge and attitude among healthcare workers. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11(1):20.

Adeleke O. Barriers to the implementation of tuberculosis infection control among South African healthcare workers. S Afr Health Rev. 2012;2012(1):197–203.

Akshaya KM, Shewade HD, Aslesh OP, Nagaraja SB, Nirgude AS, Singarajipura A, et al. “Who has to do it at the end of the day? Programme officials or hospital authorities?” Airborne infection control at drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) centres of Karnataka, India: a mixed-methods study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6(1):1–10.

Zinatsa F, Engelbrecht M, van Rensburg AJ, Kigozi G. Voices from the frontline: Barriers and strategies to improve tuberculosis infection control in primary health care facilities in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):269.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level 2016 [cited 16 February 2021]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251730/9789241549929-eng.pdf;jsessionid=D19D4759240F76F38F9324C39429AA84?sequence=1.

Al Mutair A, Alhumaid S, Al Alawi Z, Zaidi ARZ, Alzahrani AJ, Al-Tawfiq J, et al. Five-year resistance trends in pathogens causing healthcare-associated infections at a multi-hospital healthcare system in Saudi Arabia, 2015–2019. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;25:142–50.

Carlet J, Astagneau P, Brun-Buisson C, Coignard B, Salomon V, Tran B, et al. French national program for prevention of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance, 1992–2008: positive trends, but perseverance needed. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(8):737.

Kulvatunyou N, Boonbarwornrattanakul A, Soonthornkit Y, Kocharsanee C, Lertsithichai P. Incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) after the institution of an educational program on VAP prevention. J Med Assoc Thail. 2007;90(1):89.

Apisarnthanarak A, Pinitchai U, Thongphubeth K, Yuekyen C, Warren DK, Zack JE, et al. Effectiveness of an educational program to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in a tertiary care center in Thailand: a 4-year study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(6):704–11.

Yang YH, Liou SH, Chen CJ, Yang CY, Wang CL, Chen CY, et al. The effectiveness of a training program on reducing needlestick injuries/sharp object injuries among soon graduate vocational nursing school students in southern Taiwan. J Occup Health. 2007;49(5):424–9.

Cromer AL, Hutsell SO, Latham SC, Bryant KG, Wacker BB, Smith SA, et al. Impact of implementing a method of feedback and accountability related to contact precautions compliance. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(8):451–5.

Bowen A, Ma H, Ou J, Billhimer W, Long T, Mintz E, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of a handwashing-promotion program in Chinese primary schools. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(6):1166–73.

Al-Faouri I, Okour SH, Alakour NA, Alrabadi N. Knowledge and compliance with standard precautions among registered nurses: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg. 2021;62:419–24.

Thu T, Anh N, Chau N, Hung N. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding standard and isolation precautions among Vietnamese health care workers: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. Intern Med. 2012;2(4):115.

Wisniewski MF, Kim S, Trick WE, Welbel SF, Weinstein RA, Project CAR. Effect of education on hand hygiene beliefs and practices a 5-year program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(1):88–91.

Widmer AF, Conzelmann M, Tomic M, Frei R, Stranden AM. Introducing alcohol-based hand rub for hand hygiene: the critical need for training. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(1):50–4.

Chau J, Thompson D, Twinn S, Lee D, Lopez V, Ho L. An evaluation of SARS and droplet infection control practices in acute and rehabilitation hospitals in Hong Kong. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2008;14:44–7.

Cross S, Gon G, Morrison E, Afsana K, Ali SM, Manjang T, et al. An invisible workforce: the neglected role of cleaners in patient safety on maternity units. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1480085.

Peters A, Otter J, Moldovan A, Parneix P, Voss A, Pittet D. Keeping hospitals clean and safe without breaking the bank; summary of the healthcare cleaning forum 2018. Springer; 2018.

Luangasanatip N, Hongsuwan M, Limmathurotsakul D, Lubell Y, Lee AS, Harbarth S, et al. Comparative efficacy of interventions to promote hand hygiene in hospital: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351.

Neo JRJ, Sagha-Zadeh R, Vielemeyer O, Franklin E. Evidence-based practices to increase hand hygiene compliance in health care facilities: an integrated review. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(6):691–704.

Dierssen-Sotos T, Brugos-Llamazares V, Robles-García M, Rebollo-Rodrigo H, Fariñas-Álvarez C, Antolín-Juarez FM, et al. Evaluating the impact of a hand hygiene campaign on improving adherence. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):240–3.

Fuller C, Besser S, Savage J, McAteer J, Stone S, Michie S. Application of a theoretical framework for behavior change to hospital workers’ real-time explanations for noncompliance with hand hygiene guidelines. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(2):106–10.

Jang T-H, Wu S, Kirzner D, Moore C, Youssef G, Tong A, et al. Focus group study of hand hygiene practice among healthcare workers in a teaching hospital in Toronto. Canada Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(2):144–50.

Alhumaid S, Tobaiqy M, Albagshi M, Alrubaya A, Algharib F, Aldera A, et al. MERS-CoV transmitted from animal-to-human vs MERSCoV transmitted from human-to-human: comparison of virulence and therapeutic outcomes in a Saudi hospital. Trop J Pharm Res. 2018;17(6):1155–64.

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–9.

Stone SP, Fuller C, Savage J, Cookson B, Hayward A, Cooper B, et al. Evaluation of the national Cleanyourhands campaign to reduce Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and Clostridium difficile infection in hospitals in England and Wales by improved hand hygiene: four year, prospective, ecological, interrupted time series study. BMJ. 2012;344.

Moore D, Gamage B, Bryce E, Copes R, Yassi A, BIRPS Group. Protecting health care workers from SARS and other respiratory pathogens: organizational and individual factors that affect adherence to infection control guidelines. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33(2):88–96.

Gammon J, Morgan-Samuel H, Gould D. A review of the evidence for suboptimal compliance of healthcare practitioners to standard/universal infection control precautions. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(2):157–67.

Ogden J. Celebrating variability and a call to limit systematisation: the example of the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy and the Behaviour Change Wheel. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):245–50.

Elliott P. Infection control: a psychosocial approach to changing practice. Radcliffe Publishing; 2009.

Pittet D. The Lowbury lecture: behaviour in infection control. J Hosp Infect. 2004;58(1):1–13.

Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, Ford D, Hagman J, Hodge T, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(4):304–11.

von Lengerke T, Ebadi E, Schock B, Krauth C, Lange K, Stahmeyer JT, et al. Impact of psychologically tailored hand hygiene interventions on nosocomial infections with multidrug-resistant organisms: results of the cluster-randomized controlled trial PSYGIENE. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(1):1–11.

Renjun G, Ziyun L, Xiwu Y, Wei W, Yihuang G, Chunbing Z, et al. Psychological intervention on COVID-19: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020;99(21):e20335.

Latif A, Kelly B, Edrees H, Kent PS, Weaver SJ, Jovanovic B, et al. Implementing a multifaceted intervention to decrease central line-associated bloodstream infections in SEHA (Abu Dhabi Health Services Company) intensive care units: the Abu Dhabi experience. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(7):816–22.

Kingston L, O’Connell N, Dunne C. Hand hygiene-related clinical trials reported since 2010: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92(4):309–20.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank authors and their colleagues who contributed to the availability of evidence needed to compile this article. We would also like to thank the reviewers for very helpful and valuable comments and suggestions for improving the paper. We would like to thank Murtadha Alsuliman who created the cartoon.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SA, AA and ZA; Methodology: SA, and AA; Formal analysis: SA, ZA, GA and JA; Data curation: SA; Writing—original draft preparation: SA and AA; Writing—review and editing: SA, AA, AR, ZA, GA, JA, AAO and MA; Supervision: SA, AA and AAO; Project administration: SA and AA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This review is exempt from ethics approval because we collected and synthesized data from previous clinical studies in which informed consent has already been obtained by the investigators.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to this publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhumaid, S., Al Mutair, A., Al Alawi, Z. et al. Knowledge of infection prevention and control among healthcare workers and factors influencing compliance: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 10, 86 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00957-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00957-0